COVID-19 highlights the need to improve resilience and equity in managing small-scale fisheries

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic was an unprecedented health crisis in humanity’s recent history, with social and economic impacts affecting every country across the globe. The pandemic exposed the shortcomings of global health, social, and economic systems, exacerbated pre-existing gender inequalities, deepened discrimination and vulnerability1, and increased food insecurity and poverty in many countries2,3,4,5. The emerging scientific literature has highlighted the adverse impacts of COVID-19 and the policies used to respond to impacts on the fisheries sector. Valued at US$141 billion in 20206, the global seafood market (from capture fisheries) is one of the largest and most highly integrated markets in the world, thus making it highly susceptible to COVID-19 prevention policies which limited interpersonal contact, movement and cross-border trade2,4. Both large- and small-scale fisheries that trade in global markets were affected4; however, small-scale fisheries (SSF) hold particular significance for hundreds of millions of people, accounting for an estimated 90 percent of fisheries employment and providing for two-thirds of human seafood consumption7.

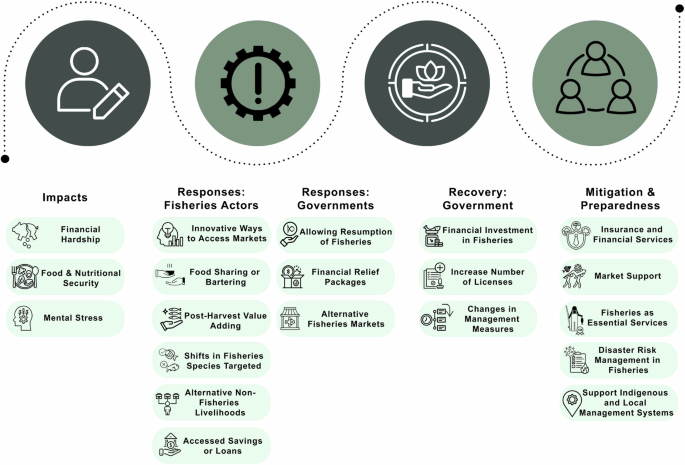

Here, we conduct a scoping review of 60 studies across 53 countries (between 2020‒2024) using the disaster risk management (DRM) framework to understand the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, the responses of fisheries actors, and the response and recovery measures put in place by governments, NGOs and private sector for SSF in diverse contexts and geographies. The DRM framework is a strategic approach aimed at understanding, managing, and reducing risks associated with disasters. It emphasises the need to identify potential hazards, assess vulnerabilities, and enhance capacities to reduce the likelihood and impact of disasters. A DRM approach is valuable because it considers not only the immediate effects of the pandemic, like the disruption of supply chains, markets, and labour, but also the long-term socio-economic impacts on those in the fisheries sector. There are four main stages to DRM cycle: (1) Mitigation involves long-term strategies aimed at reducing or eliminating risks from potential hazards (e.g. strengthening infrastructure); (2) Preparedness focuses on ensuring communities, governments, and organisations are ready for emergencies (e.g. developing disaster plans, establishing early warning systems); (3) Response are the immediate actions taken once a disaster occurs (e.g., search and rescue, providing emergency relief, protecting lives and property); and (4) Recovery is what occurs after this crisis and involves restoring normalcy, rebuilding what has been damaged, addressing the economic and social impacts, and enhancing resilience for future disasters.

We accessed the literature through search engines (e.g., Google Scholar, Research Gate) and databases (e.g., ScienceDirect, Scopus) using search strings composed of a combination of the following groups of keywords: terms for fisheries (e.g., small-scale fisheries, SSF, fisheries, fishing communities, fishers) and words that refer to the pandemic (e.g., COVID-19, pandemic, lockdown, impact). We restricted our search to only SSF identifying 60 studies in total for review (Table S1). Studies were text screened and classified by year and country. The studies were read in their entirety by the two lead authors, and categories were identified (that emerged from the literature) for: (a) the impact/problem that fishers encountered during COVID-19 (e.g., livelihoods and financial hardship, food security, stress and violence, fisheries market chain disruptions, other market chain disruptions and, other shocks and disturbances); and (b) the adaptation response by the fishers (e.g., changing livelihood, reducing catch, ask for bank loans, consume local food, direct sale of fish, among others) (Table S1). We also reported studies on how individual governments, the private sector or NGOs supported the response to, and recovery from, COVID-19 (Table S2).

We identified categories of impact from the data, paying particular attention to how COVID-19 restrictions reduced or increased resilience and inequalities within the SSF sector. We applied these insights to shed light on response and recovery strategies, with the goal of identifying post-COVID-19 pathways towards building resilient and equitable SSF and promote better mitigation and preparedness for future disasters, including pandemics. A review of this kind is highly valuable since the COVID-19 pandemic was a globally shared crisis, occurring almost simultaneously worldwide, and offering clear insights into the vulnerabilities of SSF.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on SSF actors

Disruptions to export markets were documented in 27 countries, largely associated with national lockdowns that restricted movement for non-essential services (including SSF) and curfews that limited fishing or trading times (Supplementary Table 1). Disruptions to other (non-fisheries) markets also inadvertently impacted the SSF sector. For example, closed borders resulted in a reduction in seafood demand from tourism businesses, which had knock-on effects on fisheries actors5,8,9. Fuel scarcity and high prices caused barriers to fishers conducting fishing operations, and traders supplying fish and other essential goods10,11.

Market disruptions caused three main stressors for fisheries actors—financial hardship, food and nutritional insecurity, and mental stress (Fig. 1). The most frequently reported was financial hardship caused by declines in the price of fish and/or reduction in domestic markets and local consumption. This was made worse in some parts of the Pacific where people who lost their jobs turned to fishing for food and livelihoods, oversupplying an already constricted sector9,12. Fishers and traders without access to cold storage or proper markets reported wastage of fish due to its perishable nature8,13,14,15. Fishers from India and Bangladesh who were poor at the onset of the pandemic fell into greater debt in order to survive11,16,17. Although only a few studies looked at gender inequities, a high (and often disproportionate) loss of jobs for women along SSF value chains was documented in Argentina15, Bangladesh13, India18, Kenya5,8, Mauritius19, Peru14, Thailand20, Malaysia and the Philippines21. Furthermore, fisherwomen who worked informally had limited access to life and emergency insurance, healthcare or credit13,14,22,23,24, and increased burden of care for children and relatives left many fisherwomen with less time to participate in SSF23,25.

Five policy recommendations on mitigation and preparedness to boost the resilience of the small-scale fisheries sector.

Food and nutritional insecurity affected some fisheries actors in Africa, Asia and the Pacific9,12,19,21,26,27,28,29. For example, in Bangladesh women, including those that were pregnant, were more likely to skip meals in households than men11; in contrast, everyone in the household rationed food by reducing the sizes of meals or skipping meals in St. Lucia, Kenya and Papua New Guinea5. Africa saw an increase in extreme hunger amongst women who resorted to engaging in ‘sex for fish’27,30,31, a form of gender-based violence32.

Fisheries actors experienced increased mental stress associated with declines in income, food insecurity, unemployment, fear of infection, delays in opening fishing seasons, and debt burden9,17,33. In some countries this resulted in conflict and violence. For example, men from Malawi “ganged up” against police in Mozambique to fight for fish27, and violence towards women increased in the home11,23 and in the workplace8,31. When Mozambique closed its borders, there was increased police harassment towards men and women from Malawi and Zambia, women were exposed to sexual violence (i.e., abuse and rape) by Mozambique police, and there was increased corruption and bribery to cross the borders27. Women in Malawi and Zambia organised themselves into groups and negotiated with border officials from Mozambique to ensure their safety.

Some countries experienced other serious shocks (e.g. tropical cyclones9,34, volcanic eruptions12,34, flooding events10,35, oil spills36), while coping with COVID-19, which put further pressure on authorities and the SSF sector. In other countries civil unrest and political instability occurred during (e.g. USA) or was catalysed by (e.g. Sri Lanka) the pandemic37,38.

COVID-19 response and recovery strategies

Response and recovery strategies used during and post-pandemic, provide valuable insights for increasing preparedness to future events and promoting the long-term resilience of the SSF sector (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). In the context of this paper, ‘response’ strategies were actions taken during the disaster (in this case the COVID-19 pandemic) to reduce impacts and meet the basic subsistence and livelihood needs of SSF actors; ‘recovery’ strategies were actions, post-pandemic, aimed at restoring or improving fisheries and fisheries-dependent livelihoods of disaster-affected groups or communities39. Particular attention was paid to whether response and recovery efforts addressed or widened underlying inequities in the SSF sector.

Response strategies

Fisheries actors

Fisheries actors used a range of response strategies during the pandemic to cope with and alleviate the impacts and the stressors they experienced (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). In response to market disruptions, fishers used new ways to reach markets, shared food, invested in post-harvest value adding, and shifted to different species or alternative livelihoods. Some fishers and traders used existing digital platforms (e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp) to sell fish to customers. For example, free internet coverage (for subscribers of the country’s two largest telecommunication networks) allowed many Filipino fishers to connect to customers through Facebook40. In Mexico, fishers increased their use of digital platforms to market and sell to customers23, and a women’s fishing cooperative did door-to-door sales of seafood products using their Facebook profiles25.

However, inequitable access to technology meant many fishers had to work through existing relationships and networks to create new consumer markets and door-to-door delivery. For example, a private company in Thailand provided free delivery services to help fishers distribute their products to domestic consumers41. Lack of internet access in India and Peru meant fishers were unable to access online passes to fish22. These examples highlight that while technology holds some promise in coping and adapting to disruptions to markets during a pandemic, digital inequalities meant marginalised groups (e.g. fishers, women, indigenous people, and elderly individuals) may not have access to computers, phones, and the internet, or have computer illiteracy23.

There were examples of fishers from Cameroon, Indonesia, Kenya, Liberia, Spain, Sri Lanka and Thailand targeting different species and selling value-added products to different markets8,13,41,42,43,44,45. For example, it was estimated that 10 percent of Thai fishers started to supply value-added products such as crab sauce to increase their income; others switched to higher-demand species such as jellyfish41. In Thailand, some fishermen shifted to the processing of fish, where women dominate the workforce20. In Sri Lanka, there was greater investment in value-added products and use of preservatives to reduce postharvest losses from unsold fish42,43. Switching to different species and/or producing value-added products were resilience strategies that enabled some to continue expanding into new fisheries markets during the pandemic.

To cope with financial stress, actors across diverse fisheries used their savings, borrowed money, or sold some of their assets21,26,33,43,46, while others shifted to alternative sources of income such as agricultural farming12, food and beverage sales and sewing cloth masks5,21. Examples of food sharing and bartering (including for fish) were documented in Africa45,47, Asia41, North America23 and the Pacific12,34 to cope with food insecurity.

Finally, place-based, Indigenous-led fisheries management reduced the reliance on centralised nation-state authorities48. Local authority and high adaptive capacity allowed some Indigenous Peoples to make decisions to protect their communities from the health crisis, and continue fisheries management. For example, in British Columbia, Canada, a consortium of coastal First Nations closed their borders to non-essential workers49 and chose to shut down many commercial and recreational fisheries50,51. Indigenous self-governance, stewardship programs (e.g., Haida Fisheries, Kitasoo Fisheries, Heiltsuk Integrated Resource Management Department), Coastal Guardian Watchmen programs, and locally-based co-management systems (e.g. Gwaii Haanas in Haida Gwaii), allowed First Nations to maintain key functional aspects of decision-making, enforcement, scientific surveys, and coordination of some SSF for both commercial and food, social, and ceremonial uses.

Governments

As it became clear that the COVID-19 pandemic would not be resolved swiftly, many governments implemented policies that allowed the resumption of fisheries (Fig. 1). A small number of countries provided financial relief packages or invested in alternative local seafood markets to support fisheries actors; these had variable outcomes with some reducing the pressure or economic stress faced by SSF actors, while others were ineffective or even exacerbating impacts and inequities in others.

Positive examples included: (a) Australian government introduced mechanisms to increase efficiency in selling catches locally (e.g., waiver of boat licence and quota fees, and permits for other fisheries)52; (b) Newfoundland and Labrador government invested US$400,000 to help those with fisheries-dependent livelihoods identify and establish other seafood markets53; (c) Canadian federal government provided US$470 million in grant and wage subsidies to The Food and Fish Allied Workers-Unifor union to support fisheries actors (especially fishers) impacted by the pandemic53; and (d) The Indonesian government and state-owned enterprises purchased and distributed fisheries products impacted by the closure of export markets, and US$69 million was allocated to aid small-scale fishers, fish and salt farmers, and for processing and marketing, surveillance and internal auditing of the fishing industry13.

However, there were more documented examples of financial support failing than succeeding to reach those in need in the sector. Direct financial assistance (e.g. cash stipends), relief food, and tax relief were provided to some fishers and processors by the Kenyan government, though many were not able to access this assistance8. The Peruvian government provided a small credit program (US$555) for SSF, but only about 5 percent of marine fishers benefited because many operated in the informal sector and lacked the fisher identification required to access the funds14. Fisheries actors in Fiji did not benefit from government relief and stimulus packages, as the main beneficiaries were formal businesses, agricultural farmers, and those with superannuation funds9. Despite meeting eligibility criteria, fishers were not able to access the Argentinian government’s Emergency Family Income scheme15. The Mexican government tried to provide food and cash (US$90) subsidies early in the pandemic; however, criteria for accessing support was not clear, with many, including a high proportion of women, not receiving any support23.

The designation of fisheries as ‘essential’ versus ‘non-essential’ has a significant impact on SSF actors. In the earlier parts of the pandemic, some countries banned fishing completely (e.g. Bangladesh17, India54), while others allowed small-scale fishing to continue, but under restrictions. For example in Fiji, fishers could apply for a daily pass which allowed them to fish, but they still had to comply with social distancing (which was not possible on small boats), and nightly curfew hours meant staying out to sea until early hours of the morning to avoid being arrested9. Where fisheries were seen as essential food suppliers, fishers were able to continue with their livelihoods. For example, the government of Peru allowed commercial fishing to continue during general lockdowns14, and in Argentina the collective efforts of government and NGOs resulted in the issuance of a protocol for resuming fishing in Mar del Plata, one of the largest SSF communities15. The government of Ghana considered fishing as an essential activity and implemented safety and distancing regulations; however, the distance measures were difficult to maintain when fishers were off-loading fish, hauling their canoes to berth or selling fish at the landing beach55.

Recovery strategies

Compared to impacts and responses, there is little documented in the scientific literature on what actions or investments governments made to support the post-pandemic recovery of the SSF sector (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 2). The recovery strategies that have been documented have generally not been successful and in some cases widened inequities in SSF. For example, the Peruvian government invested largely in the economic recovery of large companies even though 70% of Peru’s workforce are employed in informal sectors, including SSF, further marginalising this group. Part of this stems from the high levels of informal employment in Peru and lack of a central database housing details on those working in the SSF sector; thus making it challenging to develop and deliver financial assistance to SSF actors14. The Fijian government increased the number of SSF licences post-pandemic to promote economic growth while markets were still constricted, which reduced profit margins for fisheries actors with long-term commitments to the sector9.

A number of governments made changes to fisheries management measures or policies. Fiji reversed its fisheries management measures (e.g. seasonal closures to protect spawning aggregations, species bans) in place for the recovery of depleted species (e.g. groupers, sea cucumbers) without public consultation and counter to scientific advice and evidence, further jeopardising the recovery of these fisheries and the livelihoods that depend upon them9. While the Fiji government argued it was for food security, this argument was scientifically flawed given the multitude of other species that were available for harvesting.

There was one positive example of policy change post-pandemic. The Belize government recognised the pandemic provided an opportunity to pass legislation banning gillnets, reduce the shark fishing season and prohibit shark fishing at the offshore atolls that had been socialised and supported by the majority of fishers for over a decade. Post-pandemic monitoring found significant increases in shark abundance at two of the atolls and declines in transboundary illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing (R. Graham, unpublished data).

Our review highlights the need for improved documentation of recovery measures and their outcomes to inform future policy development. These approaches can draw on, and contribute to, global approaches to disaster response and hazard management, whatever their underlying nature. By systematically tracking the successes and challenges of recovery efforts, policymakers can identify best practices that enhance resilience. Moreover, this documentation can provide valuable lessons for managing other types of crises, including climate-related disasters. Ultimately, a more robust understanding of recovery processes will lead to more effective, adaptive policies that better support SSF actors and communities.

Looking ahead: post-COVID-19 pathways for transforming SSF

Once country borders reopened, and the COVID-19 emergency was declared officially over on 5 May 2023, there was some hope and debate on whether the pandemic would create a ‘pivotal point’ for societal transformation towards socio-cultural, environmental and economic sustainability56. Previous syntheses have focused primarily on impacts during lockdown4,5,26 but there is a need to glean lessons on responses and recovery strategies after restrictions were lifted and how these may help mitigate and better prepare the SSF sector for future events (Fig. 1, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2). There are multiple paths for future transformation of fisheries. Here, based on our review and lessons learnt through the available case studies and discussions held at a workshop in October 2022, with 24 fisheries experts (which included most co-authors), we highlight two broad areas for future investment in SSF derived from learnings gained through the global COVID-19 pandemic. Firstly, we highlight mitigation and preparedness strategies or measures that should be prioritised to boost resilience in SSF. Rather than listing all the potential ways to boost fisheries resilience, we focused on a narrow subset that emerged, in our review and expert workshop, as priorities in response to evolving global challenges, and link to the DRM framework we used. These strategies emphasise actionable approaches that address both immediate and long-term vulnerabilities in the SSF sector in an increasingly uncertain global environment. Secondly, we recommend equity and social inclusion should be integrated as core values with actionable interventions to improve the resilience of fisheries to future disturbances (e.g. pandemics, market shocks, disasters, climate change).

Boosting resilience in SSF

Lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for boosting resilience in SSF lead to five main policy options and considerations (Fig. 1): (1) improving access to insurance and financial services; (2) strengthening local and regional markets and supporting infrastructure; (3) recognising fisheries as an essential service; (4) integrating disaster risk management (DRM) into fisheries management systems; and (5) investing in Indigenous and locally-led fisheries management. These measures are important and intersect across scales, from the national and international levels to the community level, with community-led response and recovery efforts during the pandemic drawing on, and in some cases contributing to, social cohesion and ‘community spirit’.

Access to insurance and financial services

The majority of fishers worldwide lack health and life insurance and are not enrolled in social welfare and protection schemes which resulted in financial hardship. Fishers, whether their investment is in formal or informal fisheries, need access to affordable insurance schemes to protect them against losses due to disasters, market fluctuations and other uncertainties57. For example, Rare (a global nonprofit conservation organisation) is partnering with the Ocean Risk and Resilience Action Alliance (a global broking and risk solutions company) and local providers to offer parametric and microinsurance policies for the Philippines’ SSF sector, including women whose earnings are dependent on unpredictable harvests and inconsistent market prices58,59. Other organisations such as the World Bank, Asian Development Bank and United Nations Agencies (e.g. Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, UN Capital Development Fund) are trying to develop insurance schemes for SSF and fishing communities. Coupled with insurance options, is the need to develop and expand access to microfinance and credit facilities tailored to the needs of SSF actors to help them recover from financial losses and invest in sustainable livelihoods60,61. Where government funding is available for response and recovery, mechanisms should be put in place to ensure SSF actors receive financial support.

Strengthening local and regional markets and supporting infrastructure

The pandemic highlighted the need to invest in better access to local and regional markets, through cooperative marketing and improved supply chains, to reduce dependency on global supply chains, ensuring more stable local fisheries livelihoods and community resilience. Local and regional markets can empower SSF actors, especially those marginalised in global supply chains, encouraging the consumption of locally sourced fish62, reducing carbon footprints associated with long-distance transportation63 and supporting greater sustainability. Digital tools and mobile applications can provide fishers with real-time information on weather and market prices, connect them to a diversity of buyers, and ensure fisheries actors have access to critical information and resources including on disaster preparedness64. At the same time the pandemic highlighted the need to invest in infrastructure such as cold storage and processing facilities to reduce post-harvest losses, and ensure transportation enhances market access and distribution channels65,66.

Recognising fisheries as an essential service

It is important for governments to consider context specific, system-wide consequences of restrictions during pandemics and other disasters to avoid unintended consequences. We argue that SSF should be considered an essential service due to its critical role in food and nutritional security, particularly in coastal and island communities where alternative food sources are limited. Maintaining the operation of SSF ensures a continuous supply of fresh fish which is vital for public health62. Additionally, the sector supports diverse fisheries actors whose livelihoods depend on uninterrupted operations67. By deeming fisheries an essential service, governments can help sustain these communities, minimise economic impact to the sector, and ensure that aquatic food supply chains remain resilient during disturbances.

Integrating disaster risk management into fisheries management systems

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the vulnerabilities of SSF, emphasising the need to integrate DRM into fisheries management systems. ‘Disaster Risk Management’ refers to the “application of disaster risk reduction policies and strategies, to prevent new disaster risks, reduce existing disaster risks, and manage residual risks, contributing to the strengthening of resilience and reduction of losses”39. Integrating DRM can enhance the resilience of these fisheries by preparing for, mitigating, and swiftly responding to various disasters, whether they are health crises, market shocks, disasters or climate change68. A resilient fisheries management system, underpinned by robust DRM practices, can better support the sustainability and stability of fisheries livelihoods, ensuring that fisheries actors are more adaptable and capable of withstanding future crises68,69. This proactive approach is crucial for safeguarding the welfare of SSF and the ecosystems they depend on, and fosters long-term sustainability and security.

Investing in Indigenous and locally-led fisheries management

Investing in SSF which empowers and supports the environmental stewardship of Indigenous peoples and local communities represents an important pathway to effective long-term strategies to build resilience in fisheries for several compelling reasons. Indigenous and local communities often have traditional ecological knowledge and adaptive management strategies that have evolved over centuries70. Locally-led management can generate significant social and economic benefits such as creating local jobs, supporting community livelihoods, and ensuring that economic gains from SSF remain within the community71. For example, a network of community-established, locally-managed marine areas in Madagascar resulted in improved octopus catches for fishers reliant on the fishery for income72. By supporting Indigenous and local communities in stewardship and management roles, we can enhance the overall resilience of fisheries, and strengthen their resilience against future shocks, including health pandemics.

Equity and inclusion in SSF

One of the major lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic for the SSF sector is the crucial importance of equity and social inclusion considerations. The pandemic highlighted persisting or widening inequalities of access and opportunities, and the need for policies and investments to reflect more equitable systems73,74. As we reviewed the range of responses and recovery measures to COVID-19, we highlighted how those actions were applied differentially across actors and groups, with certain fishery actors (especially informal fishers and women) failing to benefit.

To improve future practices to ensure they are equitable and inclusive, there is a need for policy options and considerations such as the five listed in the earlier section, as well as opportunities to address inequalities and gaps. Some specific measures include establishing social protection for informal fishers, women and other marginalised groups, and considering context specific, system-wide consequences of restrictions and mitigation measures to minimise unequal distribution of impacts and benefits. Addressing these disparities requires targeted interventions to provide equitable access to financial resources, capacity-building programs, decision-making platforms and social protection measures75.

Another critical lesson emerging from the pandemic is the importance of having adaptive management strategies in place that can swiftly respond to changing circumstances while prioritising equity and inclusion. This requires flexible policy frameworks that can be adjusted based on real-time data and feedback from the SSF actors. Such adaptive strategies should be designed to protect the most vulnerable in the sector and ensure that recovery efforts do not exacerbate existing inequalities9,23,24. For example, some SSF actors accessed markets through digital platforms and direct-to-consumer sales models when traditional supply chains were disrupted by COVID-19; however, digital inequalities meant some groups did not have access or the literacy required to transition to such platforms. The provision of free internet and technical support to those who are not computer literate during a disaster may help SSF actors better respond and adapt to shocks.

Finally, building a more inclusive SSF sector requires fostering stronger collaborations between government agencies, NGOs, and the fisheries actors and communities. Cooperative approaches, where various stake- and right-holders work together towards common goals, share lessons learned, and leverage diverse knowledge systems to tackle future challenges are key76,77. Emphasising equity and inclusion in these collaborative efforts ensures that all stakeholders, especially the most marginalised, have their contributions valued and the needs addressed, thereby promoting a more just and sustainable future for the SSF sector73,74.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic directly and indirectly impacted SSF around the world. The lessons learned from experiences and responses during and post-COVID-19 pandemic enabled us to identify pathways to build more equitable and resilient SSF in the face of future disturbances including pandemics, market shocks, disasters and climate change. These shocks are unlikely to act in isolation and will vary in magnitude in different contexts and geographies, likely exacerbating and widening existing inequalities9,78. It is imperative for governments, philanthropies, community leaders and civil society organisations to recognise and support fisheries as essential services both in normal times and in times of crisis, to invest in and strengthen local food systems and domestic fisheries, and to mainstream equity and social inclusion and broader human rights-based approach to fisheries79,80. Future studies could focus on the recovery path after the COVID-19 pandemic ended to examine approaches taken by each country, what recovery strategies were implemented, and understand if and how business went back to normal. By learning from the pandemic, nations can build a more just and sustainable future for SSF and all those that are dependent on them for their food, culture and livelihoods.

Responses