Cross-scale consumption-based simulation models can promote sustainable metropolitan food systems

Introduction

Metropolitan food systems refer to complex networks of actors, processes and resources that are involved in production, processing, distribution, consumption and disposal of food products to feed the metropolitan area1,2. Globally, food systems contribute about 20–30% of total greenhouse gas emissions originating in human activities and are the most important users of arable land and freshwater3,4. To a large extent, these activities serve the needs of urban populations, which generally have very limited opportunities to produce their own food. Metropolitan regions are densely populated urban areas consisting of a city and its commuting zone5. Due to their massive resource consumption and waste production, metropolitan regions are responsible for most of the environmental impact of food systems6,7,8. In addition, metropolitan regions host the most vulnerable socioeconomic groups that may have scarce resources to cope with the climate impact1. Higher population density combined with a greater risk of food insecurity can in turn influence the ability of these systems to meet local needs9. Therefore, metropolitan food systems should be seen as a fundamental unit for analysing environmental and socioeconomic impacts and designing coherent policies.

Metropolitan food systems cannot be considered in isolation. They are an important source of income and employment for the local economy and are fundamentally interconnected with other key sectors like health, tourism and transport10,11. Due to the length and complexity of supply chains, metropolitan food systems are also critically integrated into the global economy12. Food products consumed in the region have a complex supply chain involving material and energy flows from a variety of sectors and regions13,14. Environmental and socioeconomic effects occur along all stages of the supply chain, from the manufacturing of fertilisers and animal feed to the final consumer. Therefore, changes in food policies and consumption patterns at the regional level can have important repercussions in other sectors and regions of the world. The transformation of metropolitan food systems into environmentally, economically and socially sustainable systems requires insights from analytical and predictive tools that in addition to the local effects, also consider the effects at the global level.

Various existing economic impact assessment models aim to capture these multilevel effects. Environmentally-extended input-output analysis (EEIOA) has been applied to the food sector to investigate its interdependencies with the rest of the economy and identify critical supply chains for reducing its environmental impact15,16. However, EEIOA focuses on input and output flows rather than the preferences and choices of local actors between different food products17. Therefore, it underestimates the importance of substitution effects associated with changes in food policies and consumption patterns within the metropolitan region and the related environmental and socioeconomic impact18,19. Computable general equilibrium (CGE) models can represent the interdependencies between income sources, demand patterns and multi-sector production structures20. Therefore, they include household budget and choices between different food products21,22. However, in most of these models supply and savings represent the fundamental drivers of the economy23. Furthermore, they usually offer a highly aggregated and stylised representation of consumption patterns24. Therefore, they are not well suited to exploring distributive effects within the region and interdependencies between the regional and global context.

In this perspective, we propose a new type of modelling framework, that combines the best out of traditional macro-economic impact assessment models with micro level simulation into so-called cross-scale consumption-based simulation (CCS) models. CCS models attribute a central role to demand and consider metropolitan systems as open systems, including cross-scale dynamics25,26,27. In particular, they enable investigating changes in the food consumption choices of local actors and their complex multilevel effects on environmental resources and socioeconomic structures across geographical scales. Recent research has linked data on individual diets to life cycle assessments (LCA) and environmental impact calculators28,29. Despite the relevance of these studies, the scope is limited to specific products, sectors and countries. We believe that it is essential to upscale these efforts in the development of analytical and predictive tools that can represent the specificity and heterogeneity of regional food consumption patterns and evaluate their environmental and socioeconomic impact on all other sectors and regions of the world.

The adoption of these modelling and simulation tools imply a fundamental change of perspective. 1. From global to local. Metropolitan regions contribute disproportionately to emissions and control activities that are crucial for reducing the food carbon footprint, such as transportation, land and energy use30,31. Most existing models either focus on the more global (or national) level, or the local, individual level without looking at interactions between the levels. CCS models acknowledge the importance of metropolitan actors and represent their interactions with other sectors and other regions of the world. 2. From processes to actors. Due to the length and complexity of the food supply chain, a transition to more sustainable consumption patterns in one region can have significant effects on production patterns in other sectors and regions12. Models like CGE take a supply driven approach with limited (often very stylised) attention to actual actors and their behaviour. CCS models acknowledge much more individual behaviour and can trace the environmental and socioeconomic effects of local food choices along different supply chains. 3. From direct to indirect effects. Changes in public policies and consumer preferences cause complex multilevel trade-offs between environmental and socioeconomic goals. More traditional models, like CGE generally only account for substitution effects at the national level, neglecting heterogeneity at the regional level. CCS models capture substitution effects between food products of different type and origin and related environmental and socioeconomic effects at the local and global level.

Metropolitan regions can drive a change in food consumption and production patterns

Consumer demand for convenience, speed and variety has expanded the supply of ready-to-eat, highly processed and non-seasonal food products32. These trends have contributed to widening the gap between production and consumption and increasing the complexity of food supply chains over time. The main implication is the reduced transparency and visibility of food production processes, with serious environmental and social consequences like air and water pollution, the diffusion of deficient and unbalanced diets and food insecurity11,12. LCA of different food products suggest that the environmental impact of production and processing is more important than long-distance transportation14,33. Given the high heterogeneity in the intensity of emissions across different product categories, changes in consumption patterns could be crucial for the sustainable transformation of food systems33,34. Therefore, reconstructing the fundamental connection between consumption behaviours and production models would contribute to the accountability of the final actors34. However, the environmental and socioeconomic effects of food production have traditionally been relegated to the rural setting35,36. Recent trends such as climate change, growing urbanisation and rising food prices have highlighted the shortcomings of this approach10.

Metropolitan regions have a crucial role in fostering economic development and employment in the food sector, while reducing food waste and pollution10,11,35,37. Larger and densely populated urban areas such as metropolitan regions contribute the most to emissions and resource consumption30,38. As complex social, ecological and technological systems, they represent a fundamental unit of analysis and policy making for adaptation to climate change39,40. They regulate activities that are crucial for reducing emissions in the food sector, such as recycling, land and energy use31. They can influence food production and distribution patterns through public procurement and regulation of health, education and sanitation41. They support the development of initiatives and schemes of food provisioning aimed at reducing the gap between production and consumption12,42. They are dynamic and interactive systems, whose effects occur on different spatial and temporal scales39. Thanks to the higher frequency and intensity of social interactions, they constitute fundamental centres of socioeconomic development40. Therefore, they can drive a change in consumption patterns from highly processed to local and seasonal products and from animal source to plant-based products with important effects on health, environment and socioeconomic fabric3,43.

It is important to mention, however, that local does not necessarily mean more sustainable. For example, even though the Mediterranean diet consists of many local products such as oil and seasonal vegetables, and can result in socioeconomic benefits in terms of opportunities for local producers, location-specific variations need to be considered as well as trade-offs (ibid). Due to the length and complexity of food supply chains, changes in consumption patterns within a metropolitan region have numerous direct and indirect effects on production patterns in other sectors, regions and countries. Therefore, the environmental and socioeconomic impact of food products expands well beyond the specific production chain.

Changes in metropolitan food consumption patterns can cause complex multilevel trade-offs

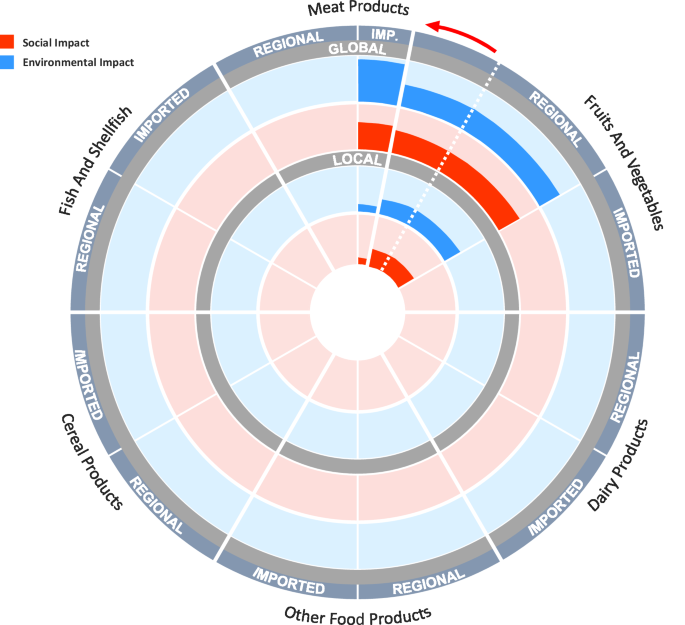

Suppose that a household residing in a metropolitan region decides to adopt a healthier and more sustainable diet, increasing its consumption of fruit and vegetables from the same region (Fig. 1). Due the existence of budget constraints, an increase in spending for a food category causes a simultaneous reduction in one or more of the remaining product categories. In this simple example, the metropolitan family increases consumption of regional vegetables and consequently reduces spending on meat products imported from other regions and countries around the world. However, these substitution effects can involve all product categories represented in Fig. 1. Therefore, changes in consumption patterns generate important substitution effects between food products of different type and origin. These effects can be identified through an analysis of household food expenses, for example through expenditures surveys. However, the environmental and socioeconomic impact of these changes can vary widely and is very difficult to predict. The literature suggests that the environmental impact of meat consumption is higher than that of fruit and vegetables3,44,45. In this respect, as previously highlighted, changes in consumption patterns in especially metropolitan populations representing the majority of consumers can help contribute towards more sustainable food systems.

The metropolitan household allocates its food budget among the following main product categories: cereal, fish and shellfish, meat, fruits and vegetables, dairy and other food products. For each category, it decides whether to buy products from the same region (regional) or from other regions of the world (imported). If the household reallocates part of its budget from imported meat products to regional fruits and vegetables, it causes complex multilevel effects along the respective supply chains. In this example, greenhouse gas emissions decrease (global), but pressure on water and land resources in the region increases (local). The total environmental impact (in blue) is lower, but it is more localised. At the same time, employment and income increase in the region and decrease slightly in the rest of the world. Therefore, the overall social impact is higher (in red) and more evenly distributed.

Nevertheless, it is still necessary to link consumption behaviours and production models, as also resource consumption and emissions depend on the type of farming and production systems46. Furthermore, as highlighted previously, regional food products are not necessarily more sustainable than imported products47. Both regional and imported food products have a complex supply chain, whose stages can be located in different sectors and regions13. The material and energy inputs used in each stage of production can also be sourced regionally or globally from a variety of sectors, causing environmental and socioeconomic effects at different levels14. The environmental impact can be assessed through indicators like greenhouse gas emissions, freshwater and land use. The socio-economic impact can be measured with indicators such as income distribution, capacity utilisation and employment. The local impact can be defined as the environmental and socioeconomic effects produced within the same metropolitan region where the product is consumed, while the global impact refers to the effects occurring in other regions of the world47.

In this example, imported meat products have a larger carbon footprint at the global level, while the production of regional vegetables increases pressure on local water and land resources (Fig. 1). Therefore, a change in consumption patterns causes a reduced, but more localised, environmental impact. However, regional produce has a more important social impact, boosting employment and income at a local level. These potential trade-offs between local and global, environmental and socioeconomic effects are implicit, as the consumer is usually unaware of the mix of inputs associated to each product and the related effects along the entire supply chain. While expenditure surveys can capture substitution effects between food products of different type and origin, these implicit multilevel trade-offs between environmental and socioeconomic effects can only be identified through consumption-based modelling tools.

EEIOA provides a useful consumption-based perspective

Input–output analysis (IOA) is a technique for predicting the behaviour of an economic system based on the interdependencies between sectors and on the relative stability of flows of goods and services48,49. EEIOA extends the flows of goods and services between sectors with environmental accounts to trace resources and emissions consumed directly and indirectly along all stages of production50,51. Therefore, it provides a useful consumption-based perspective for investigating the environmental and socioeconomic effects of the food system. It can identify the contribution of the food sector to income and employment in the rest of the economy15,52, and the combination of inputs used in the same sector, tracing their origin across different countries50. It can determine inflows and outflows of emissions33,53, competing demands for resources and critical food supply chains for reducing environmental impact16,54,55. In particular, it can be used to analyse the composition and origin of greenhouse gas emissions along the entire food supply chain and identify potential hotspots for policy interventions56. It is therefore a versatile instrument for measuring environmental impact at the regional and sector level57,58. Since all sectors and contributors to emissions are included, it provides a comprehensive assessment of environmental effects throughout the economic system59,60. The main empirical applications are the analysis of critical supply chain paths of food-energy-water flows and the determination of carbon footprints for different final consumption categories54,58. However, it can be extended to incorporate the nutritional function of different food products and the environmental factors embodied in food waste60,61. These studies indicate that the climate impact is particularly important in the production phase, with agriculture and animal husbandry consuming most resources33,53. However, further studies integrating biophysical and dietary data suggest that processing, packaging, distribution and household consumption are major contributors to fossil fuel use and greenhouse gas emissions56,62. Finally, a fundamental trade-off emerges between the use of resources for national agricultural production and industrial production destined for exports55.

The growing need for consumption-based assessment of local climate actions has encouraged the application of EEIOA to the urban carbon footprint in the global supply chain38,63,64. These local analysis increase the resolution of the national input-output tables through the nesting of single tables of regions and cities65,66. The results indicate a relocation of carbon-intensive activities to neighbouring regions, with a high amount of net imported emissions in the largest urban centres38. Income level appears to be a determining factor and more important than the density of urban structures57. Food consumption represents one of the fundamental components of the carbon footprint of metropolitan areas together with housing and personal transportation58. However, the limited availability of data on trade flows and diets at the urban level requires the adoption of scaling assumptions, limiting the reliability and generalisability of the results. Most important, EEIOA cannot capture the complex multilevel effects illustrated in the previous section. It does not include budget constraints, which may influence the allocation of scarce resources between different expenditure categories17. It does not include changes in relative prices and income distribution17,48. Therefore, it cannot account for the substitution effects associated to a change in consumer preferences and public procurement policies in favour of specific food products. These changes in preferences and policies can only be modelled through the introduction of expenditure and demand functions48,49. The introduction of CCS models allows to incorporate the food choices of the main local actors and the direct and indirect effects associated to these choices.

Cross-scale consumption-based simulation models can identify potential implicit trade-offs

The direct and indirect effects of changes in food consumption patterns in the metropolitan region can be investigated through cross-scale models, which combine the aggregation of flows and categories at the global level with a finer level of detail for the local economy. Due to the complexity of data collection and compilation, cross-scale modelling applications to the food sector are scarce and mainly limited at the regional and national level67,68. The few models that combine partial equilibrium and computable general equilibrium frameworks on a global level focus on production, investigating the effects of agricultural and trade policies, price volatility and climate shocks69,70. These models typically present a modular structure, in which the microscale is derived through the disaggregation and downscaling of national data71,72. The representation of dynamic relationships and feedback between the microscale of production and consumption and the macroscale of trade flows remains one of the main challenges for modelling the sustainable transition of food systems27. Input-output applications at local and sector levels can inform and support the construction and calibration of CCS models (Table 1).

CCS models can represent the interdependencies between the food sector and other sectors of the local economy, as well as the interactions between the metropolitan economy and all other sectors and countries of the world. The microscale should include household food choices and government food procurement patterns within the metropolitan region. The substitution effects between food products of different types and origins represented in Fig. 1 can be incorporated through specific multilevel demand functions for different actors. Their food choices can be elicited through regional statistics and expenditure surveys like the Household Budget Survey73. This information can be integrated with qualitative mapping and participatory workshops to characterise relevant scenarios, estimate the magnitude of environmental and socioeconomic effects and determine key policy goals in the specific metropolitan context74. In the event that the administrative boundaries do not coincide with the metropolitan region as defined in the introduction, it is possible to adapt the level of analysis based on data availability or collect primary data through local surveys.

The macroscale should include the complex and simultaneous interactions between demand, output and employment to account for the socioeconomic effects of these choices. CGE models represent the interdependencies between income sources, demand patterns and multi-sector production structures20. Therefore, they are the privileged tool for identifying the complex and multilevel effects of changes in consumption patterns. However, the results produced and the related economic policy implications depend on the functions and closure rules adopted75. Most CGE models build on orthodox research approaches20,24. These models are founded on the neoclassical principle of instrumentalism, which favours the ability to obtain precise predictions over the realism of the assumptions24. Typical assumptions of these models are that saving drives investment and that supply generates its own demand, while timely adjustments in prices and wages ensure an equilibrium of full employment23.

Conversely, the macro models built on the post-Keynesian and structuralist literature extend the traditional IO models with endogenous prices and income flows20,23,76,77. These models aim to identify the essential structures and mechanisms governing the functioning of the economy, avoiding oversimplified and implausible assumptions24. Typical assumptions of these models are that investment is determined independently of savings and that a lack of aggregate demand can generate states of under-employment and under-utilisation of resources23,78,79. Therefore, they incorporate the central role of demand and the complex interactions between consumption, investment, output, employment, prices and incomes. While standard CGE models adopt an atomistic approach based on representative and optimising agents, the macro models follow a more holistic approach based on the organic interdependence between groups24. Therefore, they typically include different income classes and account for the redistributive effects of economic policies75. Depending on data availability at the regional level, the microscale could be further extended through the introduction of agent-based models that represent the social structures and interactions existing between a multitude of individual agents following different sets of encoded behaviours24.

The macroscale can be calibrated on environmentally-extended input-output tables80,81. Most sources of multi-regional input-output tables like EORA, WIOD and FIGARO provide harmonised environmental satellite accounts that include greenhouse gas emissions, water and land use82,83,84. This allows to trace the direct and indirect effects of food choices in the metropolitan region across sectors and regions. A change in consumption choices in the metropolitan region first causes changes in the demand for final products and intermediate inputs used along all stages of production. Since consumption drives all other macroeconomic variables, this change also impacts investment, capital accumulation and employment. Furthermore, it has indirect effects on prices and income distribution between different classes. Finally, it causes variations in the use of natural resources and emissions associated with the different inputs used.

CCS models can be used to simulate alternative scenarios and investigate their environmental and socioeconomic impact at the regional, national and global levels. The use of explorative scenarios can support the identification of potential synergies and conflicts and the investigation of alternative pathways to sustainability in a context of uncertainty and complexity85,86. This approach is useful to investigate the indirect and unintended effects of regional government policies before the planning and implementation phase. In particular, it captures the simultaneous effects of these policies on numerous socioeconomic and environmental variables such as income, prices, consumption, investment, output, employment, greenhouse gas emissions and the use of water and land resources. Furthermore, this approach accounts for long-term and cumulative effects of regional government policies, including changes in productivity, accumulation of capital and productive capacity. Finally, potential synergies and conflict between environmental and socioeconomic goals can be anticipated.

Both changes in food consumption patterns and public policies can produce important substitution effects between food products of different type and origin, and the combination of inputs used along the respective supply chains. Returning to the example of the metropolitan household increasing its consumption of regional fruit and vegetables, these models can identify substitution effects between food products (e.g. meat, fish, dairies) specific to a region (e.g. metropolitan region of Amsterdam) or socioeconomic group (e.g. low-income household), indirect effects on prices of regional products and redistribution of income between sectors and classes (e.g. from meat processing to produce, from capital to labour). Since they are driven by consumption and demand, they can also trace the effects of these changes on the demand for natural resources, emissions, material inputs and employment from different regions of the world. In conclusion, CCS models can capture substitution effects within a region, quantify the related environmental and socioeconomic impact and identify potential implicit trade-offs at the local and global level. Therefore, they represent a fundamental tool to inform and support policies for the sustainable transition of food systems in metropolitan regions.

Responses