Crucial role of pre-treatment in plastic photoreforming for precision upcycling

Introduction

Plastics have become ubiquitous in our daily lives, primarily due to their affordability, ease of production, and remarkable durability. Since the 1950s, global production and consumption of plastics have surged exponentially, reaching 390.7 million tons by 20211. Despite their convenience, these synthetic materials are notoriously resistant to natural breakdown processes, persisting in the environment for decades2. The recycling rate of plastic waste remains extremely low, with less than 10% being recycled. The remainder is often disposed of through landfill or incineration, leading to a gradual accumulation of plastics in various ecosystems3. Most plastic degradation occurs on land, resulting in the formation of tiny particles known as microplastics, which are less than 5 mm in size4. Due to climate and environmental changes, microplastics have become widespread in the atmosphere5, terrestrial environments6, and water systems7. This widespread distribution is harmful not only to animals and plants but also to humans, as microplastics accumulate in the body along the food chain, potentially causing genetic changes and affecting brain function8.

As the detrimental effects of plastic pollution become increasingly recognized, a range of technological solutions has emerged to address the issue of waste plastics and upcycle them into high-value products9. Currently, thermal processes, including pyrolysis and gasification, are the most established methods. These processes involve the thermal breakdown of plastic waste, yielding a complex mixture of chemicals and fuels10. For instance, polyethylene (PE), widely used in household, industrial packaging, and agriculture, produces waxes and paraffins at low temperatures. When treated at a relatively high temperature, it decomposes into gases and light oils such as hydrocarbon and biochar11,12. However, the complexity of products from pyrolysis and gasification often necessitates additional steps for separation and purification13. Furthermore, certain plastics, such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyvinyl chloride (PVC), can release corrosive chemicals including Cl2 and phthalic acid, posing environmental challenges14.

Beyond thermal upcycling methods, biotechnological approaches that leverage bacteria to transform plastics into valuable chemicals offer a feasible strategy. These methods are particularly appealing due to their potential to reduce operational costs and minimize environmental impact15,16. In 2016, Yoshida et al. isolated Ideonella sakaiensis 201-F6, a bacterium with the remarkable ability to utilize PET as its primary source of energy and carbon17. This bacterium efficiently metabolizes PET, converting it into its constituent monomers, terephthalic acid (TPA) and ethylene glycol (EG). Studies have demonstrated that under controlled conditions at 30 °C, these bacteria can nearly completely degrade PET within six weeks. Building upon this discovery, Kalathil and colleagues further explored the capabilities of I. sakaiensis, revealing that this anaerobic bacterium can ferment PET to produce not only acetate and ethanol but also other value-added chemicals18. Nevertheless, the current conversion rate and efficiency of using biotechnology to upcycle plastics are limited and may not be sufficient to meet the scale of plastic waste management needs. In this context, chemical methods have emerged as more efficient alternatives. Techniques such as hydrogenolysis, glycolysis, and methanolysis, employed in industrial applications, facilitate the cleavage of C–C or C–H bonds under catalytic conditions. These processes effectively transform plastics into valuable chemical compounds, offering a promising avenue for the feasible management of plastic waste19,20,21,22. However, the cost and potential environmental impact of these methods necessitate additional consideration before their widespread utilization.

With the growing interest in solar energy, photoreforming of plastic waste has emerged as a promising method for managing plastic waste23. This technique uses solar light to convert plastic wastes into H2 fuels and valuable chemicals, such as formate, acetate, and glycolate. Unlike other plastic treatment methods, photoreforming offers a more sustainable and energy-efficient approach to polymer conversion24. It harnesses solar energy for fuel production and mitigates equipment corrosion issues associated with traditional plastic degradation methods, as it employs relatively less concentrated acid and base solution. However, the development of photoreforming is still in its infancy, with limited research and practical applications available15. Recent reviews have systematically summarized the current state of plastic photoreforming, emphasizing its feasibility and the catalysts developed in different plastic systems25,26,27. This review diverges from previous works by concentrating on the underlying principles of the photoreforming process. We explore how reaction pathways are influenced by the molecular structure of polymers and their pre-treatment methods. Additionally, we identify the existing challenges within the field and propose strategies to promote its development. Through this analysis, we aim to highlight the potential of plastic photoreforming as a future method for upcycling plastics and offer valuable insights for its practical application.

Fundamentals and developments of photoreforming

Harnessing solar energy, an inexhaustible resource, has long been a scientific aspiration. The landmark research by Fujishima and Honda in 1972 established a critical foundation in this domain, with their identification of TiO2 as a robust photocatalyst28. This breakthrough has led to significant advancements in solar energy applications for photocatalytic processes, highlighting the potential of these technologies to advance sustainable practices. Within this field, the photoreforming of plastics has emerged as a novel and particularly promising technique. In the 1980s, Kawai and Sakata made a pioneering discovery that hydrogen was generated alongside liquid hydrocarbons during the photocatalytic conversion of PVC by photocatalysis29. Their work presented an innovative solution to the plastic waste issue and established the research foundation for plastic photoreforming.

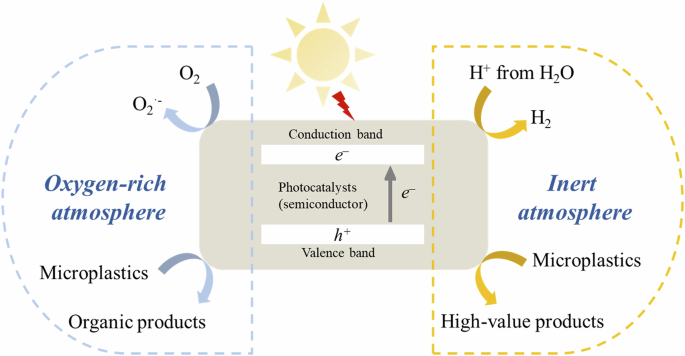

Photoreforming involves both solar water splitting and organic photoredox catalysis, as illustrated in Fig. 130. In this system, photocatalysts, typically semiconductors, play a crucial role in light absorption. When light strikes the photocatalysts, electrons (e−) are excited from the valence band (VB) to the conduction band (CB), leaving positively charged holes (h+) in the VB. During photoreforming, the excited e− reacts with protons in the reaction medium to form H2, following a reaction path similar to that of the reduction reaction in water splitting. However, the oxidation reaction mechanism varies depending on the reaction conditions. Two main strategies dominate in the h+ reaction: advanced oxidation process (AOP) and hole transfer31. The AOP commonly occurs in an O2-rich environment, where O2 reacts with the e− and/or H+ to form radicals, which then react with organics. In an O2-deficient condition, the h+ directly transfers to the catalyst surface and combines with organics to achieve oxidation reactions. A Comparison of the two reaction paths is summarized in Table 1.

A schematic illustration of reaction paths in plastic photoreforming.

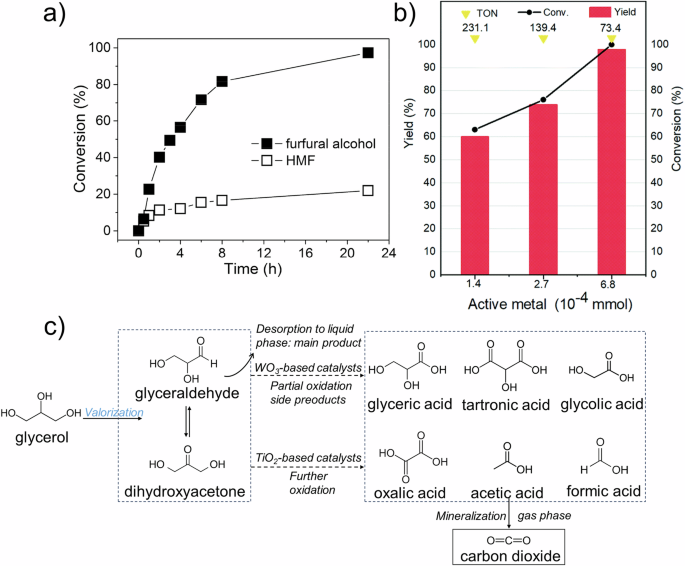

Although the first demonstration of plastic photoreforming was reported in the 1980s, subsequent development has markedly decelerated due to the complexity of polymer structure. However, photoreforming of other organics, especially biomass and solid waste, has been widely studied. The findings from these studies provide valuable insights for advancing plastic photoreforming, given the abundant similarities in the design strategies employed30. As one of the most promising alternatives for feasible energy supplements, biomass can be converted into fuels and valuable chemicals through the photoreforming process. For example, Han et al. reported a Ni-loaded ultrathin CdS nanosheet (Ni/CdS) catalyst that transformed hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF), a monomer derived from the depolymerization of cellulose, into diformylfuran (DFF) under visible light32. Although the conversion rate was modest, reaching only 20% after 22 h of photocatalysis, the selectivity for the desired product was remarkably high at nearly 100% (Fig. 2a). Building upon this foundation, in 2021, Liang et al. utilized another composite catalyst, Ni/C3N4to achieve the photo-conversion of HMF33. With efficient electron mobility from Ni and excellent light absorption ability from C3N4, a 97% DFF conversion rate with 100% selectivity was realized (Fig. 2b). In addition, food waste, typically a mix of carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids, can be upcycled by photoreforming. Studies have well-discussed the working principle of photoreforming food waste, revealing that the upcycling products vary with their original chemical compositions34. For instance, starch and sugar are considered promising substrates for bioenergy generation due to their relatively unstable structures. Zhao et al. achieved the conversion of glucose through photoreforming using a three-dimensionally ordered macroporous (3DOM) TiO2–Au composite catalyst, which enhanced light absorption and resulted in high selectivity for arabinose35. Proteins can also be upcycled by photoreforming to produce various products36. Yu et al. constructed a series of WO3/TiO2 catalysts commonly used in photocatalysis for water splitting37. Their results showed that the introduction of WO3 provided additional acidic active sites, enhancing the selectivity of C–O bond cleavage in glycerol and facilitating conversion efficiency (Fig. 2c).

a Conversion efficiency of HMF in photoreforming with 3DOM TiO2–Au composite32. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. b Photocatalytic efficiency of Ni/C3N4 in HMF conversion33. Yellow triangles: catalyst turnover (TON); black circles: conversion efficiency; red bars: product yield (%). Copyright 2021, The Royal Society of Chemistry. c Possible pathways for photocatalytic glycerol oxidation37. Copyright 2021, Elsevier.

Mechanism and reaction pathways in plastic photoreforming

Studies on photoreforming in biomass and food waste upcycling offer diverse potential strategies for the development of plastic photoreforming. However, since the first report on plastic photoreforming in the 1980s, subsequent work was not published until 2018. Compared to biomass and food waste, the degradation of plastic requires harsher conditions, and the selectivity for targeted products is much lower due to the complex structure of plastics. Therefore, specific strategies, particularly pre-treatment methods, are required for plastic photoreforming34. Many of these methods are adapted from biomass pre-treatment processes due to the significant structural similarities between biomass and plastics, such as their polymeric nature and the types of bonds connecting monomeric units38.

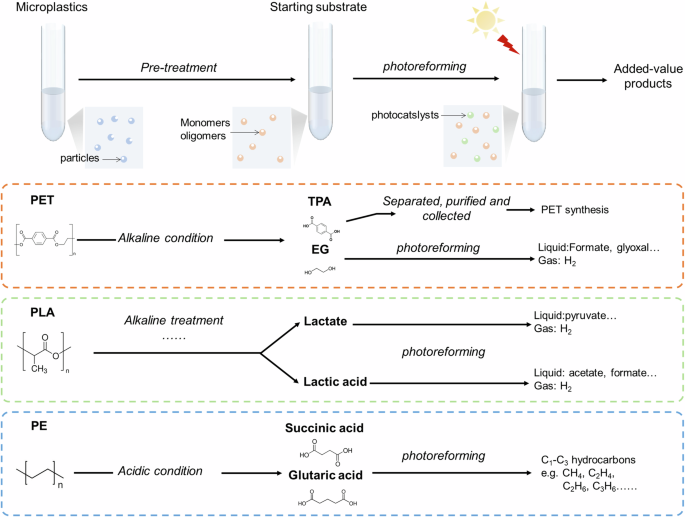

Pre-treatment of plastics is a critical step designed to enhance the efficiency of photocatalytic degradation. The process involves reducing large plastic materials into smaller particles or fragments, thereby increasing the surface area for interaction with photocatalysts. Moreover, it not only reduces the size of plastics but also can increase their solubility in the reaction medium to promote interaction with the photocatalysts23,39. Common pre-treatment methods include mechanical disintegration and chemical treatments, with the latter often utilizing acids or alkaline solutions to dissolve the plastic material40. Chemical pre-treatment, in particular, can cleave the chemical bonds within polymers, resulting in the formation of monomers or oligomers. This not only speeds up the degradation process but also modifies the initial substrate and the subsequent reaction pathway. In practice, different pre-treatment methods can produce distinct substrates from plastics, initiating various reaction paths that ultimately determine the final products of photoreforming. Therefore, precision in plastic upcycling can be significantly improved by tailoring the pre-treatment conditions to direct the reaction pathway. In this section, we examine the impact of pre-treatment on product selectivity by analyzing three widely used plastics in everyday life: PET, PLA, and PE. We reveal how the substrate’s nature, shaped by pre-treatment conditions, plays a critical role in dictating the outcomes of the photoreforming process.

Pre-treatment of polyethylene terephthalate

PET is a thermoplastic polymer resin of polyester commonly used in clothing fibers and food containers41. This type of plastic is highly resistant to biodegradation and constitutes approximately 10% of total annual plastic production and 12% of global solid waste42,43. It is of great significance to develop photoreforming technology that can convert waste PET plastics into valuable chemicals. Pre-treated PET typically yields TPA and EG as substrates for photoreforming. TPA, due to its stable aromatic structure, is not easily oxidized during catalysis, which can decrease the conversion rate of PET into valuable chemicals44. A high concentration (14.5 M) of H2SO445 is necessary during acidic treatment to prevent high pressure and temperature in the reaction vessel. However, this process generates a significant amount of inorganic salts and wastewater, and it also necessitates the recovery of H2SO4 and the purification of EG before the subsequent photoreforming process46. In contrast, alkaline hydrolysis is more efficient at breaking down polymer chains by targeting the ester bonds, resulting in EG as the predominant substrate, which is advantageous for photoreforming. In particular, the oxidation pathway of EG during photoreforming progresses through several stages. It begins with the formation of glycolaldehyde, followed by the generation of glyoxal and glycolate, then glyoxylate, oxalate, and formate. This sequence ultimately leads to the formation of carbonate ions under ideal conditions47.

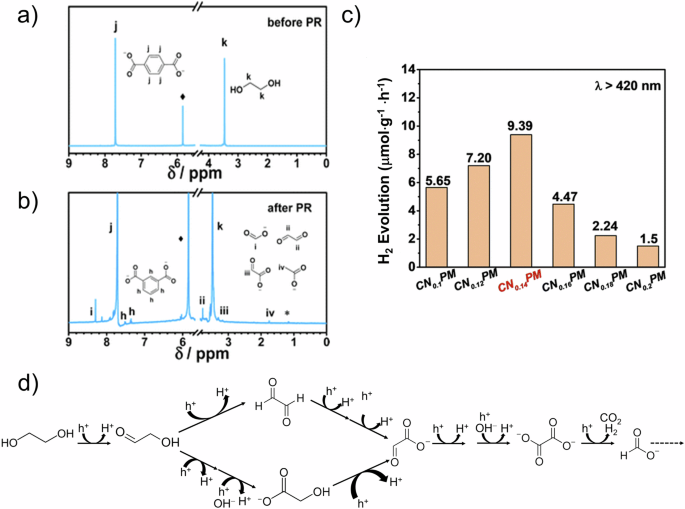

The work by Reisner et al., published in 2018, was ground-breaking in its use of non-precious metal catalysts to facilitate the photoreforming of PET under visible light in alkaline conditions48. Since then, numerous studies have also reported on the photoreforming of PET under similar alkaline conditions. In 2023, Guo et al. demonstrated a pre-treatment method for PET powder using a 2 M NaOH solution with stirring at 40 °C for 24 hours49. This process facilitated the degradation of PET into TPA and EG (Fig. 3a). Subsequently, with the assistance of a carbon nitride-based catalyst, the photoreforming process initiated with EG, resulting in the production of formate as the dominant product, along with trace amounts of glyoxal, glycolate, and acetate (Fig. 3b, c). Additionally, Zhu et al. found that pre-treatment also introduces side reactions during PET photoreforming50. In their study, under high concentrations of alkaline solution, the conversion rate of EG from PET reached as high as 81.6%. Primary products from EG conversion included formate, glyoxalic acid, and oxalic acid. Importantly, a side reaction was observed, where EG underwent hydrodeoxygenation to produce ethanol, which could further oxidize to acetate (Fig. 3d). This observation provides insight into the lower acetate content observed in Guo’s work. Similar results have been reported in other studies using different catalytic systems (Table 2). These findings suggest that tuning product selectivity in plastic photoreforming is not solely governed by the photocatalyst. Pre-treatment plays a crucial role as it establishes the initial reactants, thereby defining the feasible reaction pathways and influencing the distribution of final products. The synergy between the pre-treatment of plastics and the catalyst is decisive in determining the product profile.

1H NMR spectra a before and b after photoreforming of PET. c H2 production from photoreforming of PET using C3N4-based photocatalysts49. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2023, The Royal Society of Chemistry. d Main and side reactions of EG photooxidation50. Copyright 2024, Elsevier.

Pre-treatment of polylactic acid

Polylactic acid (PLA) is a widely used plastic derived from corn starch, commonly utilized in biomedical engineering and the manufacturing of everyday items like bags and cups51. Despite being labeled as a biodegradable plastic, PLA’s natural degradation process is slow, prompting the need for more efficient methods to accelerate its breakdown52. Alkaline pretreatment is required in most PLA photoconversion studies. As with PET, OH− in the alkaline solution can react with the ester bond carbon atoms to promote the hydrolysis of PLA into the appropriate monomers and increase the rate of photoconversion reaction. However, unlike PET plastics, PLA can yield different substrates under various alkaline conditions, which significantly impacts the subsequent photoreforming process. Therefore, selecting the appropriate pre-treatment conditions is important as it dictates the reactivity and product distribution in the photoreforming reaction.

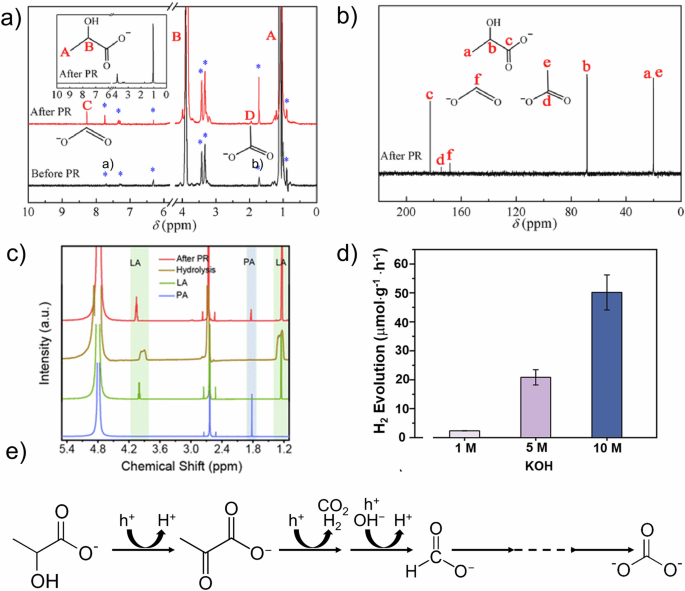

It has been reported that lactic acid is predominantly yielded in the PLA pre-treatment by mild alkaline hydrolysis. Yan et al. used a 1 M KOH solution to treat PLA, resulting in the formation of lactic acid. Using lactic acid as the initial reactant for photoreforming, acetate and formate were produced as oxidation products with the assistance of a ternary NiCoP/rGO/g-C3N4 photocatalyst (Fig. 4a, b)53. This finding was corroborated by Sun’s work, where a 1 M KOH solution was similarly used to decompose PLA into lactic acid, leading to the production of acetate and formate through the photocatalytic activity of BS-CN54. In contrast, under concentrated alkaline conditions, the photoreforming pathway varies. Liu et al. observed the formation of lactate from PLA decomposition using a 5 M KOH as pre-treatment55. In this scenario, a Ni2P/ZnIn2S4 catalytic system achieved a hydrogen production rate of 781.3 μmol g−1 h−1. Moreover, starting from lactate as the substrate, pyruvic acid emerged as the primary oxidation product with a selectivity reaching 90% (Fig. 4c). Meanwhile, Zhu et al. demonstrated that a 10 M KOH solution, as the best pre-treatment method for PLA, also hydrolyzed it to lactate (Fig. 4d)50. Under these highly alkaline conditions, the production of lactate was significantly enhanced, leading to substantial generation of pyruvate and formate as photo-oxidation products (Fig. 4e). The increased efficiency of the oxidation reaction concurrently promoted hydrogen production, achieving a remarkable hydrogen generation rate of 62.9 mmol g−1 h−1 through a CdS/NiS photocatalyst. Du et al. also employed a 10 M KOH solution as a pre-treatment method and observed the formation of lactate before photoreforming. Photo-oxidation initiated from lactate resulted in the formation of formate, along with acetaldehyde, acetate, and methanol as additional final products56. These studies demonstrate that variations in PLA pre-treatment dictate the starting substrates for photoreforming, thereby influencing the subsequent formation of photoreforming products.

a 1H NMR spectra before and after photoreforming of PLA and b 13C NMR spectrum after photoreforming of PLA53. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. c 1H-NMR spectra of products after photoreforming of PLA55. Blue line: pyruvic acid (PA); green line: lactic acid (LA); brown line: hydrolysis; red line: after photoreforming. Copyright 2023, The Royal Society of Chemistry. d Hydrogen production rates with PLA pre-treatment using alkaline solutions of different concentrations and e proposed reaction scheme for the photo-oxidation of LA50. Copyright 2022, Elsevier.

Pre-treatment of polyethylene

PE represents another class of plastics that holds potential for upcycling through photoreforming. PE is a thermoplastic resin synthesized from ethylene monomers via polymerization, widely utilized in the production of films, packaging, and more. The backbone of PE, comprised of C–C bonds, endows it with notable stability, resistance to acids and bases, and excellent insulating properties. However, these characteristics also present challenges for PE upcycling, as the C–C bonds are resistant to cleavage. Developing suitable pre-treatment strategies and photocatalysts capable of efficiently disrupting these stable bonds is a pivotal challenge, with the ultimate goal of enhancing the sustainability of PE waste management56.

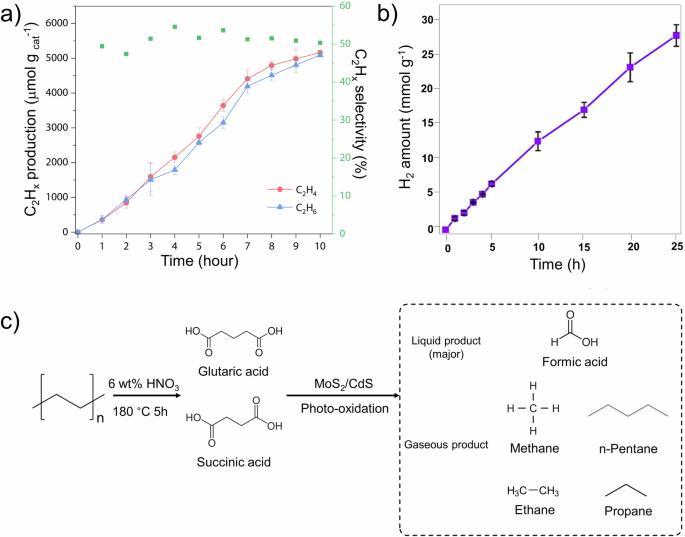

PE pre-treatment is predominantly executed under acidic conditions due to its increased susceptibility to acidic environments. However, unlike the pretreatment of PLA and PET, where OH− directly interacts with the plastic molecules, the acid treatment of PE usually involves oxidization and thermal decomposition of PE, rather than the direct action of acid. This acidic pre-treatment typically yields organic acids such as succinic, glutaric, and formic acids, which are precursors to C1 to C3 gaseous products in the photoreforming process. Although the photoreforming process presents significant challenges, there have been some successful examples. For instance, Pichler et al. discovered that higher concentrations of HNO3 did not significantly affect the yield or product distribution of the pre-treatment products57. After pre-treatment with 6 wt% HNO3, PE was primarily decomposed to succinic acid (44%) and glutaric acid (22%). During the photoreforming process, C2H6 (derived from succinic acid) and C3H8 (from glutaric acid) were produced. Zhang et al. placed PE powder into 7% HNO3 and heated it at 160 °C for 8 h to complete the pre-treatment process58. This process decomposed PE into succinic acid and glutaric acid (Fig. 5a). During the photoreforming process, these acids were catalyzed into C2 and C3 hydrocarbons, such as C2H4 and C2H6, using a Pd1-TiO2 catalyst (Fig. 5b). Additionally, propionic acid was detected as a liquid-phase product from the oxidation of succinic acid. In another study, Du et al. used 6 wt% HNO3 as an oxidant, reacting PE in the solution at 180 °C for 5 h56. After this heat treatment, a 10 M KOH solution was used to neutralize the pH of the supernatant. As a result, the reaction solution mainly contained formic acid, succinic acid, and glutaric acid (Fig. 5c). Through the photoreforming process, PE photoreforming mainly generated CH4 as the oxidation product and additional CO2 using a MoS2/CdS catalyst.

a C2 hydrocarbon production and selectivity for catalysts in 3 h of photoreforming58. Green square: C2Hx selectivity; red circles: C2H4; blue triangles: C2H6. Copyright 2023, AAAS. b H2 evolution from photoreforming of pre-treated PE on MoS2/CdS for 25 h. c Schematic illustration of PE oxidation into carboxylic acid and the subsequent photoreforming process over MoS2/CdS56. Copyright 2022, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Conclusion and perspectives

In summary, the growing interest in photoreforming underscores its potential in addressing the plastic waste crisis. The success of this technology in upcycling biomass and food waste provides valuable insights for its application in plastic waste management. However, the critical role of pre-treatment in plastic photoreforming is often undervalued. Pre-treatment not only reduces particle size and increases the solubility of plastics but also affects the thermodynamics and kinetics of the reactions. Modifying the starting substrate alters the reaction pathways and mechanisms, thereby influencing the overall efficiency of plastic photoconversion. Our review of current research on PET, PLA, and PE photoreforming highlights the transformative potential of tailored pre-treatment strategies in achieving the selective production of valuable chemicals from waste plastics (Fig. 6). This emphasizes the need for a comprehensive understanding and optimization of pre-treatment processes to enhance the efficacy and sustainability of plastic photoreforming.

Schematic illustration of pre-treatments in photoreforming and the corresponding processes and product summary of PET, PLA, and PE photoreforming.

However, the practical implementation of pre-treatment strategies encounters several challenges. While concentrated hydrolysis solutions can effectively accelerate reaction rates, they also introduce harsh conditions that may compromise the overall process. These strong reagents can affect catalyst stability59 and characteristics60, complicating the separation and purification of organic products. For example, concentrated alkaline environments can damage the integrity of permeable membranes used in purification, hindering the efficient extraction of target products61,62. The environmental impact and economic costs associated with using concentrated alkaline or acidic solutions are critical considerations. Additionally, pH is a significant factor influencing the reaction process. For instance, with Pt SA catalysts, photocatalytic hydrogen production is significantly higher under acidic conditions compared to alkaline and neutral conditions, due to changes in the Pt–H interaction63. In light of these challenges, there is growing interest in innovative pre-treatment methods. Techniques such as plasma or microwave-assisted methods are emerging as viable alternatives that could optimize the pre-treatment environment and address issues encountered in subsequent stages of the photoreforming process64. Additionally, photoreforming is currently limited to laboratory-scale applications and requires further evaluation on a larger scale to assess its real-life practicality, including factors such as energy returned on energy invested (EROI) and the cost-effectiveness of recycling30,65. Reisner et al. have established a pilot plant to investigate changes in EROI, carbon footprint, and production costs by evaluating parameters such as photocatalyst reuse and efficiency, aiming to determine the economic and environmental feasibility of the entire process. It is important to acknowledge that the cost-effectiveness of plastic photoreforming remains low compared to other treatment methods, such as heat treatment, which poses a significant obstacle to its large-scale application.

Our comprehensive analysis reveals that pre-treatment is the pivotal determinant in substrate generation, which significantly influences product yields and selectivity. Advancing this concept and integrating these findings with machine learning techniques could lead to the creation of predictive models. Such models would enable researchers to strategically design reaction conditions tailored to produce specific end products from different types of plastic waste. We believe this innovative approach, merging data-driven predictions with experimental design, is poised to significantly enhance the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of precision upcycling processes. It represents a transformative step towards the development of sustainable management strategies for the future.

Responses