Cultivation of bovine lipid chunks on Aloe vera scaffolds

Introduction

Cellular agriculture aims to revolutionize traditional farming practices by addressing environmental, animal welfare, and sustainability concerns. Cultured meat (CM) is the cultivation of animal cells in vitro to create edible tissues1,2,3,4,5,6. However, achieving cost-effectiveness and reliability for large-scale food production remains a critical challenge. Generally, tissue growth necessitates source cells, a three-dimensional support structure, and a scaffold capable of allowing perfusion for adequate nutrient delivery and waste removal, as well as nutrients, including amino acids and growth factors7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22.

An ideal scaffold must provide an optimal cell attachment, growth, and differentiation environment. Balancing porosity with mechanical properties is crucial since larger pore sizes enhance cell infiltration and tissue formation, but excessive porosity compromises mechanical strength23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Thus, scaffold design must carefully optimize tissue formation without compromising structural integrity. The use of edible byproducts in CM is also intensely examined, aligning with sustainable practices and leveraging renewable, animal-free resources.

Our study explores the potential of utilizing Aloe vera parenchymal cellulose (AVPC) as a scaffold material for CM. Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) is a perennial xerophyte used for medicinal and food applications. Its leaves store water in parenchyma cells containing viscous mucilage, a.k.a Aloe vera gel, primarily composed of polysaccharides, enzymes, minerals, and organic acids, with a water content exceeding 98%1,2,3,4,5,6. Industrial extraction methods involve mechanical filleting, followed by chopping and juicing the Aloe vera leaves, leaving the cellular material as pulp32,33. The dried parenchyma residue retains compositional similarities to the gel and is rich in mannose-containing polysaccharides, cellulose, and pectic polysaccharides, as well as galacturonic acid (34%, w/w)34,35,36. Global Aloe vera production is estimated at 300,000–500,000 metric tons annually, with average yields of 2–5 metric tons per hectare depending on regional conditions and farming practices37,38.

Cellulose, nature’s most abundant polymer, is a key structural element of the cell wall of plants, which gives the cell its mechanical strength and rigidity. Due to its biocompatibility and mechanical properties, cellulose is commonly used as a scaffold material in tissue engineering. Researchers have successfully prepared cellulose from bacterial sources and decellularized plants, such as spinach, bamboo, algae, apple, and Aloe vera.7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Aloe vera cellulose-based scaffolds have been used for engineering tissues such as skin and cornea and in regenerative medicine applications such as wound healing23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31. Aloe vera pulp is FDA-approved as a food additive for human consumption due to its safety and compatibility with food-grade applications39. It is commonly used in beverages worldwide, and industrial processes have been developed to preserve its nutritional properties, similar to those used in the cosmetic industries40,41,42,43.

Notably, the leftover parenchyma is appealing to the cultivated meat industry because of its neutral taste, form factor, and texture, resembling a fish fillet. To summarize, AVPC is a byproduct that offers structural support and tissue architecture while delivering the appearance and nutritional characteristics required for a scaffold for CM production. Here, we produced and characterized sterile AVPC-based porous scaffolds and validated their biocompatibility potential with animal cells and, importantly, bovine mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) relevant to the CM industry. Next, by changing the media composition, we have turned the bMSC-loaded-AVPC scaffold into ’lipid chunks.’ Lastly, we show the potential utility of using this scaffold within a novel macrofluidic single-use bioreactor (MSUB)44. This approach promotes sustainability by utilizing renewable resources and is potentially scalable in a scale-out model, solving some of the technical challenges CM faces45. Thus, our study addresses the need for cost-effective and scalable bioprocessing solutions by incorporating scaffolds and bioreactors, aiming to advance biotechnology applications for tissue engineering and CM production and also opens intriguing culinary possibilities for improving the taste and texture of other alternative protein products.

Results

Aloe vera scaffold properties

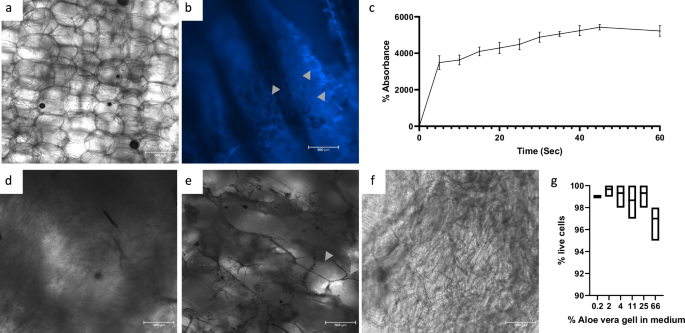

Aloe vera parenchyma has a large cell wall structure made mostly from cellulose encompassing large cells in a honeycomb-like structure (Fig. 1a). To visualize the cellulose, we stained it with Calcoflour white (Fig. 1b). Likely due to its hydrophilic properties, the lyophilized scaffold exhibits a high and rapid liquid retention capability, as demonstrated by an absorption assay (Fig. 1c). After autoclaving, the structure of the cells collapses, and the gel is poured out of the parenchymal tissue, leaving a mesh of cell wall (Fig. 1d). After lyophilization, the cellulose structure remains, and the porous structure of the scaffold is revealed (Fig. 1e). Rehydrating the scaffold creates a cellulose mesh that retains water (Fig. 1f), hereafter referred to as the AVPC. Additionally, evaluating Aloe vera autoclaved gel for toxicity by adding it to the medium showed little toxicity to the cells, suggesting the scaffold itself may be biocompatible for tissue culture (Fig. 1g). After washing in DDW or DMEM, the pH of the scaffolds was 4.72 in DDW and 7.78 in DMEM, validating a compatible environment for cell growth.

a Fresh Aloe vera parenchyma exhibiting honeycomb-like structure. b Fresh Aloe vera parenchyma stained with Calcoflour white. c Water absorbance assay for freeze-dried Aloe vera scaffolds (n = 3). d Autoclaved Aloe vera parenchyma. e LyophilizedAloe vera parenchyma. f Rehydrated Aloe vera parenchyma. g Aloe vera gel toxicity assay using NIH/3T3 fibroblasts 0.2–66% Aloe vera gel (n = 3) (scale bar: 500 μm).

Proliferation and tissue formation of mammalian cells on Aloe vera scaffolds

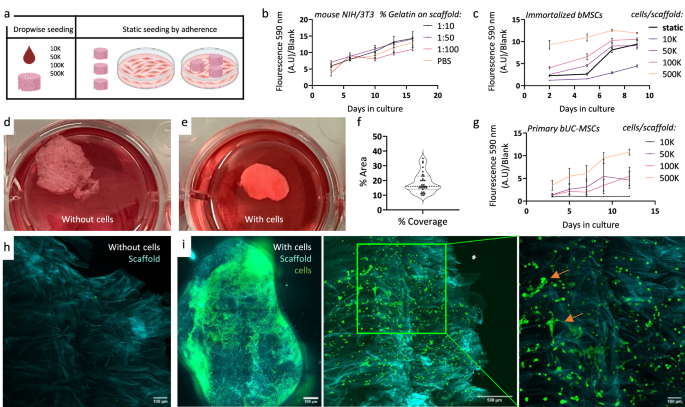

The biocompatibility of Aloe vera scaffolds was examined on NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts with or without gelatin addition. We employed two types of seeding methods (Fig. 2a), and proliferation measurements were conducted using Alamar blue reagent serving as an indicator for cell viability and proliferation. Cells seeded on scaffolds with different gelatin concentrations demonstrated no discernible difference in proliferation rate, indicating that the inclusion of gelatin did not improve the cell’s initial adhesion or proliferation (see Fig. 2b). Therefore, we haven’t used gelatin in the following experiments. Next, we wished to examine the compatibility of AVPC scaffolds with immortalized bMSCs and to compare two cell seeding approaches: drop-wise vs static adherent seeding. Our findings indicate that the static seeding method yielded favorable results in terms of cell proliferation (Fig. 2c). This comparison underscores the importance of optimizing cell seeding techniques to maximize cell growth and scaffold colonization. Interestingly, these scaffolds exhibited significant visual differences from those without cells, visible to the naked eye (Fig. 2d, e). The scaffold appeared clear in the negative control, where no cells were seeded, with the cellulose mesh visible (Fig. 2d). Conversely, scaffolds with proliferating cells became visually distinct, forming white balls that were smaller and smoother than the negative control scaffolds (Fig. 2e). This visual contrast underscores the colonization and proliferation of cells on the scaffold and might indicate successful cellular integration as the cells adhere to the scaffold and pull it to form a smaller shape than the original. Coverage analysis from confocal images of 8mm scaffolds cultivated with immortalized bMSCs shows a heterogeneous distribution, with an average of 20% coverage observed across the scaffold surface. However, coverage varies considerably, ranging from 0% to 40% in different areas of the scaffold (Fig. 2f). The proliferation of primary umbilical cord-derived bMSCs on the scaffolds was also evident over time (Fig. 2g). Confocal microscopy of the scaffolds post-cultivation without (Fig. 2h) and with (Fig. 2i) the immortalized bMSC cells expressing GFP revealed dense cell coverage and thus further corroborate the findings of the Alamar blue metabolic assay. The bMSCs are attached well, display spindle-like morphology characteristic of MSCs, and form dense colonies, reminiscent of conditions observed in dense 2D cultures (Fig. 2i right, orange arrows). Notably, in the absence of cells, the scaffold itself does not exhibit fluorescence (Fig. 2h). Together, these results indicate that bovine stem cells, such as MSCs commonly used in the CM industry, thrive on the AVPC scaffold.

a Illustration of seeding methods for scaffolds drop-wise vs static adherent seeding. b Proliferation assay for 50K NIH/3T3 fibroblasts seeded on Aloe vera scaffolds with gelatin in different concentrations 1:10–1:100 and without gelatin (n = 3). c Proliferation assay for immortalized bovine MSCs seeded on Aloe vera scaffolds in different drop-wise cell seeding concentrations and with 2D adherent seeding (n = 3). d Macroscopic image of scaffolds post cultivation without or (e) with immortalized bMSCs. f Coverage plot of immortalized bovine MSCs. g Proliferation assay for primary bovine umbilical cord-derived MSCs seeded on Aloe vera scaffolds in different cell seeding concentrations (n = 3). h Confocal microscopy of scaffold without cells and i GFP expressing bMSCs (green) on the scaffold (cyan) (scale bar: 500 μm or 100 μm).

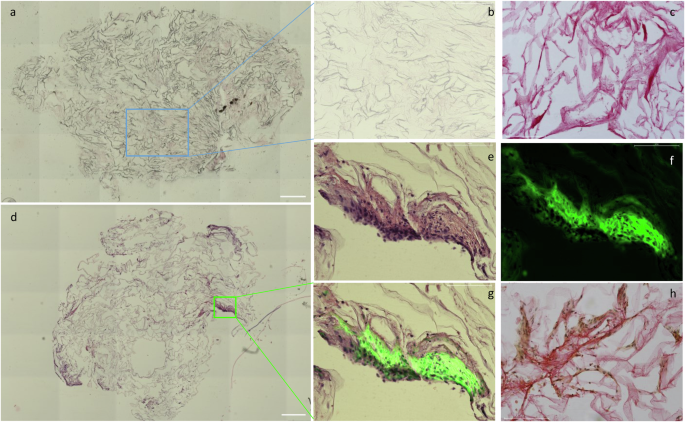

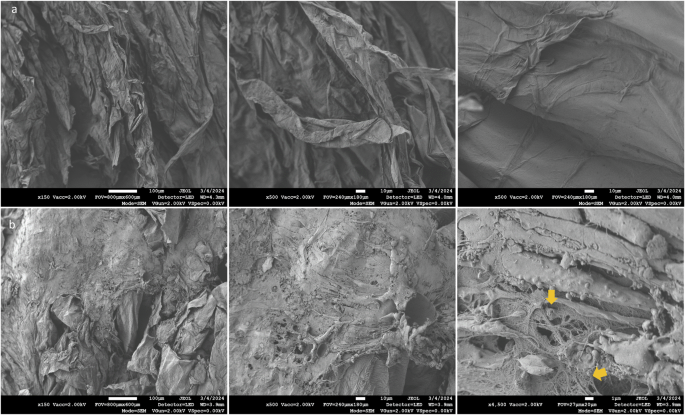

Histologic sectioning of the empty (Fig. 3a–c) and the MSC-carrying AVPC scaffolds (Fig. 3d–h) provided further insight into the gradual formation of tissue-like structures on the scaffold. Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained section from 10 mm deep, near the scaffold center, stitched to show the whole scaffold (Fig. 3a, d), showing dense structures made from cell and extracellular matrix (ECM) on the periphery. Zooming into these areas demonstrated many ECM-secreting, GFP-positive cells growing on the AVPC (Fig. 3e–g). Picrosirius red staining indicates the presence of collagen fibers, which appear red under microscopy (Fig. 3g). In contrast, cell nuclei stained with hematoxylin exhibit a purplish-blue hue, while the extracellular matrix and cytoplasm stain pink with eosin. The notable coloration of Fig. 3g, as compared with the scaffold without cells presented in Fig. 3c, indicates enhanced collagen deposition within the scaffold, directly correlating with the proliferation of the bMSCs. This possibly reflects the scaffold’s successful integration and remodeling by bMSCs and underscores the efficacy of our approach in promoting tissue formation on the AVPC scaffold. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of Aloe vera scaffolds without cells shows the arrangement of collapsed cellulose cell walls resulting from the fabrication process (Fig. 4a). Following cell cultivation, SEM images revealed that cells are visibly organized into tissue-like structures, with the extracellular matrix prominently interspersed between them (Fig. 4b, yellow arrows). Together, the histology and SEM imaging not only underscores the scaffold’s capacity to support cell adhesion and proliferation but also hints at its ability to foster the formation of complex, three-dimensional tissue architectures.

a Representative H&E image of horizontal sections of scaffolds without cells (scale bar: 500 μm) and b enlarged image of the H&E or c picrosirius red staining done on a sequential section from the same scaffold as panel (b) (b, c scale bar: 275 μm). d. H&E representative images of a horizontal section of the scaffold with bMSC (scale bar: 500 μm) and e enlarged image of a tissue-like formation, also observed by f GFP labeling of the cells and g merged image. h picrosirius red staining done on a sequential section from the same scaffold as panel (d) (e–h scale bar: 175 μm).

a Top-view SEM images of Aloe vera scaffolds without cells (scale bar from left to right: 100 μm, 10 μm, and 1 μm). b Top-view SEM images of bMSCs growing for 12 days on Aloe vera scaffolds (scale bar from left to right: 100 μm, 10 μm, and 1 μm).

Maturation and fat accumulation of MSC grown on Aloe vera scaffolds

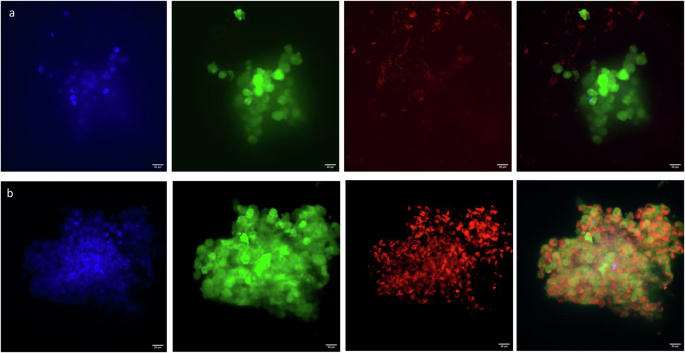

The overarching objective of this study is to establish a proof of concept for producing lipid chunks by incorporating food-grade natural scaffolds carrying bovine stem cells into the novel MSUB platform. To achieve this goal, our approach leverages the structural stability of the AVPC scaffolds, which are stable in agitation in liquid and at 37 °C, for extended durations. Their stability was tested for up to 68 days, with the potential to endure even longer (see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Video 1). Maturation of the scaffolds post-proliferation was conducted in the MSUB and wells, and confocal imaging was used to assess the cells’ viability and growth and lipid droplet accumulation in the oleic acid-induced culture.

As expected, cells cultivated without oleic acid supplementation exhibited minimal staining of fat (Fig. 5a). In contrast, in the scaffolds treated with oleic acid, the cells displayed robust staining with Nile red, revealing the presence of lipid droplets (Fig. 5b).

a Representative images of cells after 14 days in standard media culture or in b standard media + 300 μm oleic acid for 2 days. Images are maxed projections of 5 μm confocal stacks. Data represent two independent experiments: blue: nuclei, DAPI; green: cells, GFP; red: lipid droplets, NileRed. The scale bar is 20 μm.

Discussion

The alternative protein sector must devise sustainable solutions to address global challenges such as food insecurity and climate change46. In this context, using byproducts from various industries aligns with the sector’s goal of reducing production costs and minimizing environmental impact by repurposing waste materials47,48. Here, we describe the resourcing of Aloe vera parenchyma, a byproduct from the cosmetics and beverage industries, as a scaffold for cultivating bovine stem cells to produce lipid chunks.

The incorporation of Aloe vera parenchyma as a scaffold offers several advantages for CM production. Primarily, the porous nature of the scaffold, derived from processed parenchyma, facilitates high liquid retention properties, providing an optimal environment for tissue culture applications. This characteristic is pivotal for sustaining cell viability and promoting cellular growth, ultimately contributing to the development of high-quality CM products8,12. Moreover, using industrial byproducts aligns with the sector’s goal of reducing production costs and minimizing environmental impact by repurposing waste materials. The scaffold production process utilizes two methods, steam sterilization (autoclave) and freeze drying; both processes are used in the food industry and require no addition of other materials contributing to a clean food label15.

In addition to being FDA-approved and sold globally in drinks and as raw pulp, Aloe vera chunks and juice are considered by many customers to be healthy food and are often sold in organic food shops as wellness products49. These properties of Aloe vera make it suitable for an industrial food process while enjoying preliminary customer acceptance.

Our experimentation yielded promising findings regarding the structural integrity of the Aloe vera scaffolds during the cultivation process. While in parallel to cultivation in multiwell plates in static conditions, we have evaluated the scaffold under agitation by air in an MSUB from filtered air pumped into the cultivation chamber44. The scaffolds remained intact, showcasing their robustness and suitability for bioprocessing applications (See Supplementary Video 1). This unique mechanical property is why we use a whole parenchymal explant, unlike other scaffolds that may have a leaf shape or made out of powder, that will not withstand strong agitation and will not appear as a piece of meat. The fact that our production method doesn’t require scaffold polymerization and reinforcement steps such as 3D printing, foaming, and cross-linking15 may pave the way to a scalable and simple industrial process.

Furthermore, our observation that gelatine did not enhance the scaffolds suggests that the Aloe vera parenchyma scaffold may possess intrinsic properties conducive to CM production, potentially reducing scaffold fabrication costs in industrial settings.

Fat tissue primarily comprises adipocytes containing lipid droplets, which are crucial in determining meat quality and influencing attributes like juiciness, flavor, and nutritional value. These lipid droplets contain neutral lipids, notably triacylglycerols (TAGs), which can be broken down into fatty acids by lingual lipase in the mouth. The formation of lipid droplets within the scaffold impacts cultivated meat’s nutritional composition and taste. Moreover, fatty acids contribute to meat flavors by generating volatile compounds through oxidation. While we have shown lipid accumulation in bMSC grown on AVPC scaffolds, we must assess the transcriptional shifts accompanying adipocyte differentiation and explore other tissue differentiation protocols, such as towards muscle. Consequently, the observations regarding adipogenic buildup require further substantiation in forthcoming studies utilizing primary bMSCs.

Adopting macrofluidic single-use bioreactors represents a novel approach in the CM industry, offering a range of benefits, including reduced capital expenses, rapid prototyping capabilities, and flexibility in optimizing production processes. The idea of a maturation bioreactor fits with current strategies of large-scale CM production50 and adipose tissue cultivation protocols51, where the first step is to expand the cells in suspension and later to seed them on scaffolds and cultivate them in perfusion.

The design of either overhead aeration (as demonstrated in ref. 44) or with an airlift by simply using tubes of varying lengths. Given that different scaffolds demand different agitation mechanisms and aeration techniques, had we applied the current design to puffed rice, the outcomes would have been detrimental, leading to a lack of proliferation. Also, while our present bioreactor design necessitates manual media replenishment, the quick fabrication method enables the incorporation of pumps52 and sensors. This paves the way for an alternative perfusion bioreactor design that facilitates automatic media replacement through perfusion. Potentially, with the right kind of agitation and liquid handling, the whole process of expansion and maturation can be done in one MSUB.

The synergy between Aloe vera scaffolds and macrofluidic single-use bioreactors underscores the potential for innovative solutions in the alternative protein sector. This bioprocess holds promise for creating bovine fat-like chunks as additives in plant-based meat alternatives. By capitalizing on existing byproducts and harnessing bioprocessing technologies, our study contributes to expediting the transition toward sustainable and efficient CM production, addressing the escalating demand for protein sources while mitigating environmental impacts8,44. Further optimization of cell distribution could involve reducing scaffold diameter or employing advanced agitation techniques, such as packed beds or mechanical-stimuli bioreactors. These strategies may improve nutrient and oxygen diffusion, minimize surface accumulation, and support uniform cell growth within the scaffold. Overall, our study suggests that Aloe vera scaffolds support mammalian cell proliferation and tissue formation. The repurpose of Aloe vera parenchyma, a byproduct of the existing Aloe vera gel production industry, presents a simple and sustainable solution for the CM industry. The bioprocess using AVPC scaffolds holds promise for producing bovine fat-like chunks, which can be used as additives in plant-based meat alternatives or as a step toward creating ’whole cut’ CM products. When integrated into macrofluidic single-use bioreactors, these Aloe vera scaffolds not only support mammalian cell proliferation and tissue formation but also reinforce sustainability goals by reducing capital expenses associated with traditional tissue culture infrastructure and potentially facilitating scalability in a scale-out model, meeting the dynamic demands of the CM industry. In essence, this paper emphasizes the potential of AVPC scaffolds to overcome current challenges in CM production and pave the way for innovative solutions in the alternative protein sector.

Methods

Aloe vera scaffold production

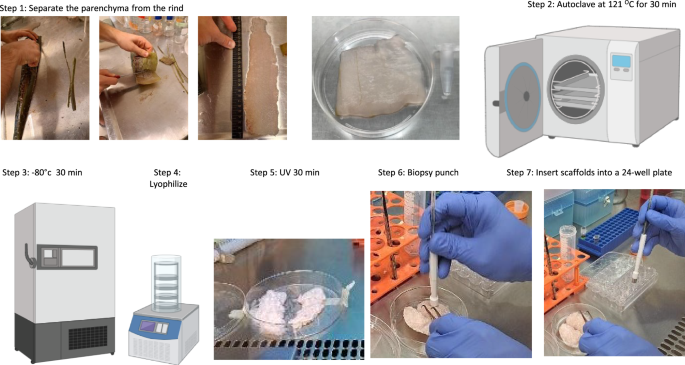

Fresh Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) leaves were obtained from a local farm (Just Aloe, Ein Yahav, Israel). Parenchyma tissue was separated from the rind using a knife as illustrated in Fig. 6; the tissue was then autoclaved for 30 min in glass jars. Subsequently, the gel was extracted using a vacuum pump in a laminar flow hood, and the remaining parenchymal cellulose was placed in a lidded 15 cm Petri dish to maintain sterility. The dish was then stored at −80 °C for 30 min until completely frozen, then transferred to a freeze dryer (Biobase, BK-FD102) for 48 h until the plate was not cold, indicating complete dehydration. The lyophilized tissue was then exposed to UV light in a laminar flow hood for at least 30 min for sterilization. Afterward, we used an 8mm biopsy punch to punch out plugs from the lyophilized tissue, and each punch was used as a scaffold. These scaffolds were placed in 12/24 Corning Costar Non-Treated Multiple Well Plate. The bottom of the wells was coated with 300/100 μl of BIOFLOAT FLEX coating solution (Facellitate, F202005) and incubated at room temperature for 3 min to prevent cell adhesion. The liquid was then removed, and the plates were left open to dry in the laminar flow hood for 30 min. For gelatin incorporation in AVPC, gelatin solutions were prepared by dissolving gelatin powder in double-distilled water (DDW) at 40 mg/ml. To determine the amount of gelatin required for each scaffold, the weight was multiplied by the desired gelatin percentage, divided by the weight of gelatin in milligrams, and then multiplied by 1000 to convert to milliliters. The necessary phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) volume was obtained by subtracting the calculated gelatin amount from the scaffold’s absorption capacity, which was determined via prior swelling assays. The gelatin was then mixed with this PBS volume. To account for variability in absorption across scaffolds, the mixture was scaled up based on the number of scaffolds, with the total volume doubled. Scaffolds were immersed in the gelatin-PBS solution for a time defined by swelling assay results, frozen at −80 °C for 20 min, and lyophilized for 24 h to complete the process.

Aloe vera leaves were brought into the lab, and the parenchyma tissue was separated from the rind with a knife, cleaned, and measured (step 1). The tissue was autoclaved for 30 min at 121 °C in a glass jar (Step 2), and the remaining parenchymal cellulose was placed in a sterile Petri dish, frozen at −80 °C (Step 3), and freeze-dried for 48 h (Step 4). Lyophilized tissue was sterilized under UV light for 30 min (Step 5). Using an 8 mm biopsy punch, scaffolds were created (Step 6) and stored in non-treated multi-well plates with a coating solution to prevent cell adhesion (Step 7).

Aloe vera scaffold pH and water absorbance assay

Controlled water additions of 10 μl and subsequent wet weight measurements allowed for the calculation of water absorption. Wet weight measurements following each addition facilitated the calculation of percent water absorption using the formula [(wet weight − dry weight)/dry weight] × 100], which yields insights into the hygroscopic properties of the scaffolds. Scaffolds were measured for pH in the presence of 2 ml water or Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) with a pH meter (Eutech pH 700, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Aloe vera gel toxicity assay

Autoclaved Aloe vera gel was added to low glucose DMEM basal medium with 10% FBS, 1% mixture of penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine in different concentrations (0.2–66%). Each well was seeded with 55,000 NIH/3T3 cells on a 24-multiwell tissue culture plate (for each concentration n = 3). The cells were then incubated with the gel for two days. Afterward, cells were trypsinized and counted, and the percentage of live cells was determined by trypan blue staining using a cell counter (TC20 automated cell counter, Bio-Rad).

Macrofluidic single-use bioreactor

The macrofluidic single-use bioreactor was fabricated as described in ref. 44,52. The flexible tube connected to the pump was introduced into the MSUB under the liquid surface, the flexible tube allowed air out of the MSUB above the liquid phase. At the top, there is a screw cap cut from a standard 15 ml tube and secured with a zip tie, which is used as a port to introduce scaffolds and liquids into the MSUB (See Supplementary Fig. 1).

Cell culture and immortalization

Bovine mesenchymal stem cells (bMSCs) were isolated, cultured, and characterized based on generally accepted criteria53,54 as in ref. 55. The primary cell line immortalization was achieved by introducing simian virus 40 large T antigen (SV40T, a kind gift from Prof. Sara Selig) by transient transfection, and the human telomerase gene hTERT (addgene 191920,56) by retrovirus-mediated transduction. The cells were grown in low-glucose Dulbecco modified eagle medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco) and a penicillin-streptomycin mixture (1%) and cryopreserved in fetal bovine serum containing 10% DMSO. GFP-expressing cells were made using pLKO_047 (Broad Institute) lentiviral vector and Puromycin selection. Generally, all cells were plated in a low-glucose Dulbecco-modified eagle medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, United States) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% l-glutamine and a penicillin-streptomycin mixture (1%). For Umbilical cord-derived bMSCs, 1mM of bovine FGF2 was supplemented to the media.

Proliferation assay

To assess metabolic activity in live culture, we applied Alamar blue reagent, which operates by converting resazurin to resorufin. Resazurin, initially a non-fluorescent indicator dye, undergoes reduction reactions in metabolically active cells, resulting in the formation of highly red fluorescent resorufin. Cells were seeded in wells at 10,000 (10K) to 500,000 (500K) cells per scaffold, in a seeding volume of 30 μl. Static adherent seeding was done by placing the scaffolds on a confluent plate for two days. Following seeding, the scaffolds were placed in a non-treated, Biofloat©coated 12 or 24-well plate and incubated for 45 min at 37 °C. Then, 2 ml of growth medium was added to each scaffold. The scaffolds were carefully transferred to a new plate using sterile tweezers. The cells were maintained in 2 ml of low glucose DMEM basal medium with 10%FBS, 1% mixture of penicillin-streptomycin, and 1% l-glutamine. Cultivation was done in an incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Subsequently, wells were incubated for 4 h with 2 ml of a solution comprising a 10:1 ratio of growth medium to Alamar Blue reagent stock solution, 3.6% Alamar Blue (Thermo Scientific, 88951). A hundred microliter of the medium was transferred to a clear 96-well plate, and fluorescence readings were taken using a plate reader (BioTek Synergy HT Multi-Mode Microplate Reader; Agilent Technologies, Inc), and the fluorescence was measured at 590 nm following excitation at 520 nm. Next, the medium in each well was replaced with 2 ml of fresh medium and 4 ml in the MSUB and flasks. As a control, we seeded 5000 and 50,000 cells on 2D culture plates without scaffolds 24 h before plate reader analysis. The negative control consisted of the growth medium, Alamar Blue reagent, and the blank was a scaffold without cells. Cells were seeded drop-wise in 24 μl or by adherent seeding, where we placed the scaffolds on a 10 cm tissue culture plate with 2.7 million adherent cells. We left the scaffolds on the plate for two days, and then, using sterile tweezers, we transferred the scaffolds to a Biofloat©-coated multiwell plate.

Maturation in MSUB

After 10 days in wells, six scaffolds with an Alamar reading of 8–10 were moved to two MSUBs (three scaffolds in each) with 6 ml media for 48-h maturation. Next, 300 mM oleic acid was added to one MSUB while the other kept the proliferation media. The air pump was placed in the incubator and programmed to provide intermittent CO2-enriched air from the incubator passed through the filter into the MSUB as the tube was aerating close to the bottom of the culture chamber, leading to agitation akin to an airlift bioreactor.

Histology

The following methods were employed to prepare histological sections of Aloe vera scaffolds for analysis. First, Aloe vera scaffolds were fixed using a 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution for 24 h. After fixation, the samples were dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol (70%, 80%, 90%, 95%, and 100%) for 1 h each and cleared using xylene for 1 h. Subsequently, the dehydrated and cleared samples were followed by embedding in paraffin wax blocks. Once embedded, the paraffin blocks were cooled, solidified, and then sectioned into thin slices (5–20 μm thick) using a microtome. We used H&E (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) for cells and extracellular matrix staining. We used picrosirius red (Direct Red 80, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) to detect collagen secretion. The slides were stained with hematoxylin, eosin, or picrosirius red, according to the standard staining procedure. In short, the slides were deparaffinized in HistoChoice®Clearining Agent, rehydrated through a graded series of ethanol, and stained with hematoxylin for 6 min, followed by 1 h of picrosirius red. After staining, the slides were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted with a coverslip using a mounting medium. Finally, the histological sections were observed under a light microscope and imaged using EVOS M7000 (Invitrogen).

Microscopy

Scaffolds were stained at room temperature using Calcofluor white (3 μl/ml and washed with PBS). For fatty acid imaging, Scaffolds were stained with 1 μg/ml−1 Hoechst (Thermo Fisher, 62249) for nuclei and 0.1% v/v Nile red (Thermo Fisher, N1142). Fluorescence imaging was performed either using an Inverted Nikon ECLIPSE TI-DH fluorescent microscope or by Confocal imaging using a Leica SP8 Confocal Microscope or imaged live with a BC43 Benchtop Confocal Microscope (Oxford Instruments). SEM images were acquired by a JSM-7800F field emission scanning electron microscope; the scaffolds were dried with a K850 critical point dryer and coated with a Q150T ES Plus at 18mA for 90 sec with 2 nm AuPd.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 9.00 (GraphPad Software). Variables are expressed as mean ± SEM. The figure legends detail specific statistical tests.

Responses