Current hydroclimatic spaces will be breached in half of the world’s humid high-elevation tropical ecosystems

Introduction

Climate change is recognized as one of the major threats to global biodiversity1,2. As the climate changes, the current distribution of hydroclimatic conditions and the range of the species will move and rearrange spatially3. High-elevation ecosystems are particularly vulnerable to this threat due to their narrow and strict elevational distribution4,5,6 and their restricted extent: they cover less than 3% of the global terrestrial area outside Antarctica7. These ecosystems are expected to shift rapidly poleward and upward in response to accelerating climate change in mountain regions8, potentially contracting or even disappearing altogether9,10,11. This shift raises major concerns about the persistence of these invaluable ecosystems, the pressures on their biodiversity, and the resilience of their ecological functions to provide essential ecosystem services5,6,10,11,12,13,14.

Humid high-elevation ecosystems in the tropics, hereafter HETEs (sensu Suarez et al15.), mainly occur in the Neotropic, Afrotropic, and Australasia between the upper treeline at about 3500 m.a.s.l16,17 and the lower permanent snow line at approximately 5000 m.a.s.l. (Fig. 1A)11,18,19. These ecosystems have regional names, such as páramos and jalca in the Northern Andes or afroalpine and moorlands in East Africa20. HETEs are the most biodiverse among high-elevation ecosystems, hosting the highest species richness and endemism21,22,23,24. For instance, HETEs in the Northern Andes host about 3500 vascular plant species, of which approximately 60% are endemic, and thousands of vertebrate species21,22. The distribution of HETEs is naturally fragmented16, but land use changes have increased their isolation in recent decades25,26,27, further constraining the dispersal capacities of species28,29. The effects of climate change on biodiversity are then expected to be an interaction of movement, adaptation, or local extinction mechanisms at the specific level11,12,30.

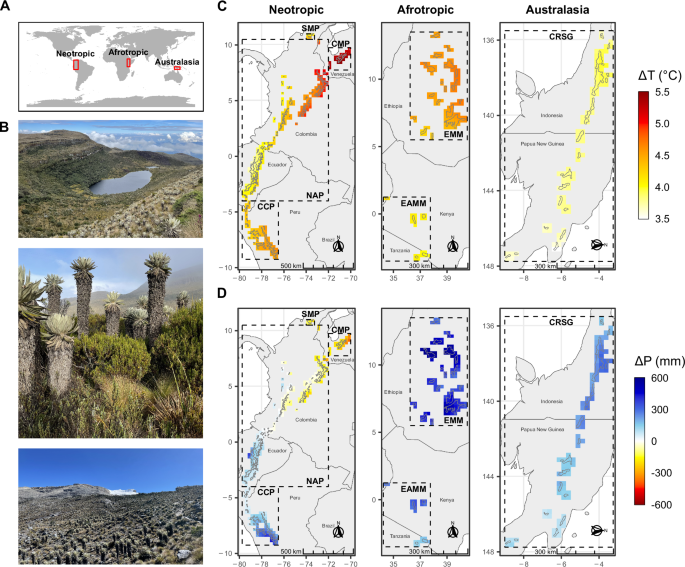

A General location of HETEs in the world. B Examples of HETEs landscapes, top: Laguna de Cajitas, Sumapaz National Natural Park, Colombia (credits: Picture by Adriana Sanchez, 2022); mid: Frailejones or Espeletia and other páramo vegetation types, Guantiva – La Rusia páramo complex, Colombia (credits: Picture by Adriana Sanchez, 2021); bottom: Upper páramo limit, El Cocuy National Natural Park, Colombia (credits: Picture by Adriana Sanchez, 2022). C Change in mean annual temperature T. D Change in total annual precipitation P in the seven humid high-elevation tropical ecoregions (SMP: Santa Marta Páramo; CMP: Cordillera de Merida Páramo; NAP: Northern Andean Páramo; CCP: Cordillera Central Páramo; EAMM: East African Mountain Moorlands; EMM: Ethiopian Mountain Moorlands; CRSG: Central Range sub-alpine Grasslands). The dotted lines mark the ecoregions. Fig. S1 shows the spatial distribution of the standard errors among Coupled Model Intercomparison Project Phase 6 (CMIP6) General Circulation Models (GCMs).

HETEs are also crucial for their services to people and society11,13,31,32. They represent important carbon stocks due to topography and climate, promoting the formation of mineral soils and wetlands rich in organic carbon33,34,35. As a result of their climatic, edaphic, and vegetation properties, HETEs have an exceptional water regulation capacity, which is essential for water supply to millions of people in surrounding cities and communities14,36,37,38. For instance, many large Andean cities depend on HETEs for up to 95% of their water supply11,16. This water supply also contributes to hydropower production, food security, and socio-economic development11,14. Climate change is expected to impact the water balance of these ecosystems, their regulating capacity, and downstream water supply11,14,32,36,37,38,39.

Although HETEs are highly vulnerable and crucial for biodiversity conservation and socio-economic development, they remain among the world’s most understudied and poorly characterized ecosystems11,40. Research on these ecosystems has increased in the last decades6,10,11,13,32,41, primarily focused on the impacts of land use change and human activities in these ecosystems6,10,11,13,32,41. However, understanding the implications of potential climate-related range shifts of HETEs worldwide is also necessary4,38,42 for impact assessment. It is also required to propose practical management approaches that ensure the conservation and resilience of HETEs, their services31 and the design and implementation of effective restoration43.

Predicting the potential impacts of future climate change on the extent and distribution of HETEs and identifying the most vulnerable and resilient HETEs to changes is thus crucial for biodiversity conservation and human well-being in and around these ecosystems. To do so, there is a need to understand the hydroclimatic spaces in which HETEs currently thrive; these present the thresholds within which these ecosystems can persist. Hydroclimatic spaces are the envelope of multidimensional water and energy-related conditions over a given period44,45. Since these hydroclimatic spaces are expected to change over time under climate change scenarios, one can compare current or baseline and future or projected ones to identify areas where baseline hydroclimates could be breached under the influence of climate change44,45.

Modeling of hydroclimatic spaces has been previously used to reconstruct and draw inferences about past climates from paleo-ecological data46,47,48 and assess projected changes in temperature and precipitation from regional to global scales6,10,49,50,51. The use of hydroclimatic spaces to analyze the potential impacts of climate change on HETEs has, to date, mainly focused on the Andes at local scales6,10, leaving those of the Afrotropics and Australasia unassessed. Furthermore, these efforts have considered only the long-term mean temperature and precipitation, leaving aside seasonality and extremes of these variables, which are pivotal to predicting and understanding the ecosystem and biodiversity responses of HETEs to climate change52,53,54.

Here, we explore on an ecoregional basis the potential impacts of future climate change on the extent and distribution of HETEs globally based on the high emissions Shared Socioeconomic Pathway (SSP) scenario without carbon emission mitigation strategies, SSP585. Specifically, we use a multimodel ensemble of climate data from the latest NASA Global Daily Downscaled Projections archive (NEX-GDDP-CMIP6)55 and the Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World (TEOW) dataset Version 2.056 by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to assess changes in temperature and precipitation (from 1985–2014 to 2071–2100) in HETEs across three continents and seven ecoregions (Fig. 1A–C). We use this data on precipitation and temperature to define the baseline hydroclimatic spaces and their potential projected breaching. Lastly, we discuss the implications of our results for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem services provision.

Results

Projected hydroclimatic changes in global HETEs

Based on the mean of six GCMs of the historical and high-emission SSP585 of the CMIP6, we find that temperature (T) will increase more in the ecoregions of the Northern Neotropics, with warming reaching about +5.5 °C in the Northern Andean Páramo (NAP) and the Cordillera de Merida Páramo (CMP) (Fig. 1A–C). The change in total annual precipitation (P) is spatially less consistent than temperature (Fig. 1D), increasing in most ecoregions and mainly in the Ethiopian Mountain Moorlands (EMM), except for the ecoregions in Northern South America, where drier conditions will emerge. Northern South America emerges as the region where HETEs will experience the most intense warming and drying across the Tropics.

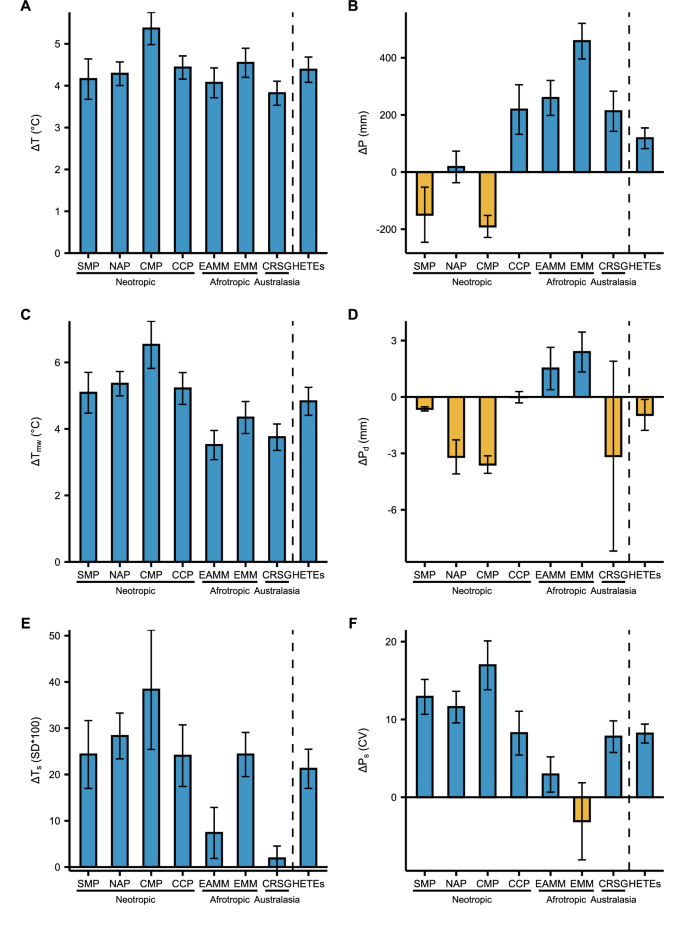

Beyond the long-term (LT) changes in T and P, changes in climatic extremes (EX) and Seasonality (SE) are critical to understanding projected climate change impacts on HETEs. The long-term T (Fig. 2A) is expected to increase with a similar spatial pattern as the maximum temperature of the warmest month (Tmw; Fig. 2C), with the East African Mountain Moorlands (EAMM) in the Afrotropics and the Central Range sub-alpine Grasslands (CRSG) in Australasia experiencing the overall smallest changes. On the other hand, although P will increase in more than half of the ecoregions (Fig. 2B), the precipitation of the driest month (Pd; Fig. 2D) will decrease in most ecoregions, accentuating dry extremes, especially in the Neotropics. Precipitation seasonality (Ps; Fig. 2F) and temperature seasonality (Ts; Fig. 2E) will also increase consistently across most ecoregions and biogeographical realms, following the trends observed in the long-term means and extremes of temperature.

The parameters include: A mean annual temperature T, B total annual precipitation P, C maximum temperature of the warmest month Tmw, D precipitation of driest month Pd, E temperature seasonality Ts, and F precipitation seasonality Ps. Changes are calculated between 1985–2014 and 2071–2100 for each of the seven ecoregions and HETEs overall. Error bars show the standard errors of the six GCMs. Fig. S2 shows the reference (1985–2014) and the projected (2071–2100) mean values of the six hydroclimatic parameters for each ecoregion.

Baseline and projected hydroclimatic spaces

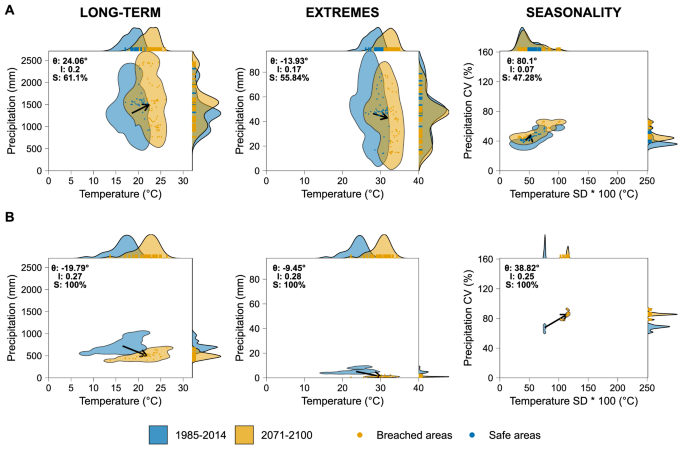

We have constructed a two-dimension hydroclimatic space for the baseline long-term (LT), extremes (EX), and Seasonality (SE) conditions in each HETE ecoregion based on the corresponding selected variables describing water and energy availability (See Table 1). By constructing them likewise for the future, we are able to calculate the changes in these hydroclimatic spaces over time and reveal the potential impacts of climate change on HETEs. The magnitude and extent of the trajectories represented in the hydroclimatic space by these changes differ among ecoregions, as expressed by their direction (θ), intensity (I), and severity (S) of change (Fig. 3; Fig. S3): geometric parameters used to assess the characteristics of the change (see methods). For instance, the Central Range sub-alpine Grasslands of Australasia (CRSG; Fig. 3A) will experience conditions of energy and water availability in the future period 2071–2100 that fall outside of the three current baseline hydroclimatic spaces (i.e., LT, EX, SE) across half of the HETEs spatial extent (i.e., area of the yellow polygons without intersection with the blue polygon).

A Central Range sub-alpine Grasslands (CRSG) and B Cordillera de Mérida Páramo (CMP). Polygons represent the hydroclimatic spaces, and arrows represent the mean trajectories of their change as expressed by the movement of the centroids of the polygons between 1985-2014 and 2071-2100. The direction of change in degrees (θ) is measured from the right horizontal, accompanied by the normalized intensity of change (I), and the severity of the change (S) is defined as the percentage of the future polygon breaching the boundaries of the current one (See Methods section). Points represent projected values of future hydroclimatic parameters and are colored according to their geometric intersection with the baseline hydroclimatic space of the respective ecoregion. Marginal plots show the 1-dimensional 95% Kernel Densities for the hydroclimatic parameters. Table S1 shows the 95% confidence intervals and standard errors of the indicators from the six CMIP6 GCMs used to build the multimodel ensemble of climate data.

We refer to areas within both blue and yellow polygons as safe hydroclimatic spaces since the future hydroclimatic conditions experienced by the HETEs are within the envelope of conditions of the current baseline. Conversely, we refer to the areas of yellow polygons not intersected by the blue polygons as breached hydroclimatic spaces, as future hydroclimatic conditions will be outside of the envelope of current baseline hydroclimatic conditions.

In the case of the Cordillera de Merida Páramo in the Neotropics (CMP; Fig. 3B), the full ecosystem’s spatial extent will experience conditions falling outside the envelope representing the baseline LT, EX, SE hydroclimatic spaces. In this sense, we refer to a full breach of the hydroclimatic space in CMP in the future (i.e., S = 100%). In addition, the intensity (I) of the breaching is highest in CMP, judging by the separation between current and future envelopes of temperature and precipitation. Breaching the LT and EX baseline hydroclimatic spaces is primarily due to the increasing temperature rather than precipitation changes (lower θ) in both CRSG and CMP ecoregions.

As the hydroclimatic conditions change in the high-elevation tropical ecoregions, future temperature and precipitation will lead to conditions falling even beyond the baseline hydroclimatic spaces of any of the HETEs found globally. An extreme case is that of CRGS, where future hydroclimatic conditions in precipitation and temperature will surpass the current conditions of all HETEs. This will result in 41% and 26% of the ecoregion extent experiencing novel long-term and extreme hydroclimatic conditions, respectively (Fig. S4; Fig. S5). Hence, these HETEs will potentially be under novel hydroclimates and may become novel ecosystems44,45,49,57,58.

Vulnerability of HETEs to climate change

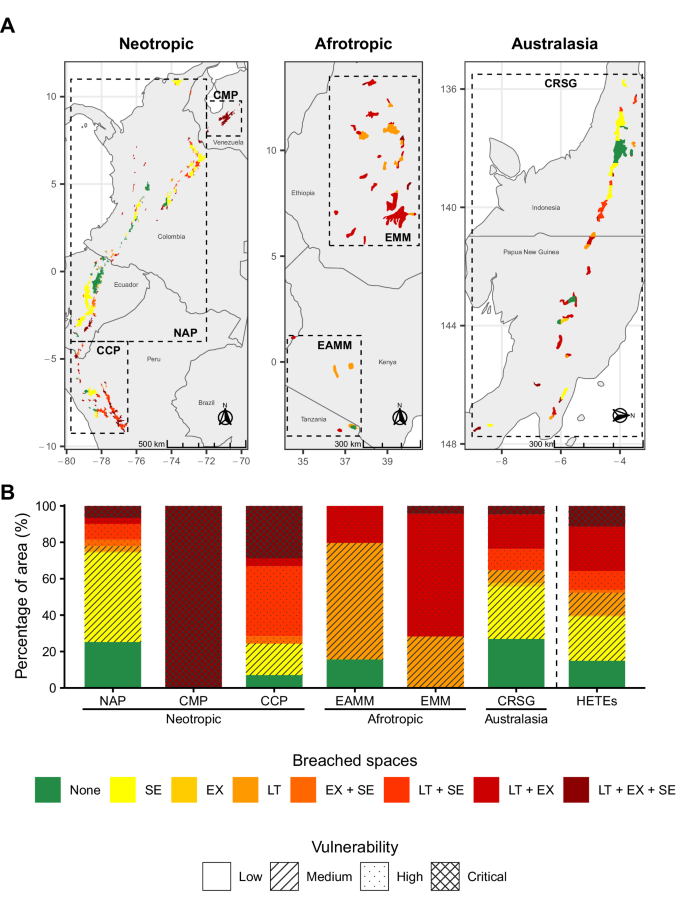

Locating and quantifying the safe and breached hydroclimatic spaces helps determine the overall vulnerability of HETEs to climate change. The most vulnerable HETEs are concentrated in the Neotropic, particularly the CMP and CCP ecoregions, where the three hydroclimatic spaces (LT, EX, SE) will be simultaneously breached in 100% and 30% of their spatial extent, respectively (Fig. 4; dark red). In the Afrotropic, the vulnerability level is medium to high, with most of the ecoregion’s extent experiencing breaching in one (yellow to light orange) or two safe hydroclimatic spaces (dark orange to red). On the contrary, 25% of the spatial extent of NAP and CRSG have low vulnerability to change as they will remain in safe hydroclimatic spaces across (green). Finally, it is worth noting that ecoregions such as NAP or CRSG present a varying range of vulnerability levels due to their ample spatial coverage and the variability of their orographic conditions.

Classification of vulnerability to climate change in each ecoregion based on A Location and B percentage of spatial extent. Colors in A and B represent the combinations and severity of the breached hydroclimatic spaces: long-term (LT), extreme (EX), and seasonality (SE), with green representing no hydroclimatic space breached, and dark red for all three hydroclimatic spaces breached. The patterns translate the number of hydroclimatic spaces being breached into vulnerability categories.

Overall, only 15% of all the HETEs’ spatial extent will have a low vulnerability to climate change, conserving their safe hydroclimatic conditions under the three hydroclimatic spaces. In contrast, about 10% of the spatial extent of HETEs will have their hydroclimatic space breached under all three dimensions, resulting in critical vulnerability, and around 40% will have at least two of their hydroclimatic spaces breached in the future (high vulnerability). This raises concerns for the survival of HETEs by the end of the century.

Discussion

Our results show the projected changes in hydroclimatic conditions of HETEs by 2100 under the SSP585 scenario. For instance, in the Neotropics, HETEs will experience regionally variable changes in precipitation, with increments in the south and reductions in the north. Ecoregions in the north will be the only ones to face simultaneous warmer and drier conditions. These patterns are consistent with previous studies that have explored the projected temperature and precipitation changes over the Andes and South America6,59,60,61. Similarly, other studies agree with the increasing temperature and precipitation patterns we found for HETEs in Africa62,63 and Australasia64,65 at continental and regional scales. The consistent temperature increments and shifts in precipitation found in this study, which lead to the breaching of the hydroclimatic spaces in the seven ecoregions, could eventually reduce suitable climates for these ecosystems and drive the emergence of novel climates within HETEs. The capacity of high-elevation tropical species to face climate change impacts and avoid local extinctions could be conditioned by the persistence of safe hydroclimatic spaces, their dispersal abilities for reaching analog climates, as well as their capability to adapt to novel climates3,12,30,66.

Our findings suggest potential breaching within the safe hydroclimatic spaces and increased vulnerability to climate change that will likely affect the persistence of isolated populations and increase the extinction risk of species. This would be particularly impactful in ecoregions such as CMP where, according to our results, HETEs will virtually disappear by 2100. Some studies have indeed assessed the projected impacts of climate change on the biodiversity of HETEs. For instance, it has been reported that species such as Polylepis quadrijuga from the Northern Andean treeline or species from the emblematic Espeletia complex are highly vulnerable to climate change and will face large reductions in their distribution under future climate change scenarios67,68. In the CMP, 28 Espeletiinae endemic species are projected to lose, on average, 77% of their geographical extent by 207069. In the Afrotropic, tropical alpine giant rosette plants such as the endemic Lobelia rhynchopetalum are projected to face a very high risk of extinction and losing 82% of their genetic diversity by 2080 due to range reduction and isolation29. Similarly, about 75 species from the humid high-elevation ecoregion in New Guinea will disappear by 2070 under RCP 8.5 scenario64.

This study also suggests that projected increments in temperature and the overall changes in hydroclimatic spaces toward novel conditions will likely produce upward shifts in the HETEs’ vertical distribution in the search for suitable hydroclimatic conditions. With restricted cross-mountain dispersal opportunities due to the expected increment in fragmentation, the extent of elevational range and vertical dispersion capacities of high-elevation tropical species will become critical factors in determining their risk of extinction when facing this threat. These elevational climatic shifts impact birds and plant species with narrow vertical distributions and dispersal constraints because their thermal niches could be surpassed faster, and their capacity to track climate changes moving upward is limited12,70,71,72. Furthermore, high-elevation tropical species have shown to be more responsive to warming by shifting their range upwards faster than high-latitude montane species73. For instance, it has been reported that Andean plant species can migrate upward from 7 m/decade74 to 25 m/decade73. Therefore, in HETEs with lower maximum elevations, such as in the Afrotropic and Australasia, species with distributions limited to the highest elevations will face a higher extinction risk69, as they will have less space to move upward and may be caught in climatic traps12.

The breaching of the safe hydroclimatic spaces in some HETEs (Fig. 3; e.g., CMP and CCP) will induce changes in the physiological and functional response of high-elevation tropical vegetation to climate stress and modulate species’ adaptation. Temperature stress in HETEs is mainly mediated by the differences in the night-time freezing temperatures and the day-time high temperatures, as well as by the seasonal variations in temperature75,76. Our results show overall consistent increments in T and Tmw of about 4.5 °C and 5 °C in HETEs, respectively, which could increase stress (and plant death) by high day-time and dry-season temperatures. However, the increments could also alleviate night-time freezing stress as rising temperatures are expected to push the frost line upward. These changes will likely benefit the less freeze-resistant species while negatively impacting those more sensitive to high temperatures and evaporative demand.

Water stress in HETEs is mainly accentuated during the dry season when soil water availability decreases and the air evaporative demand increases75,76. Projected reductions in P and Pd in some ecoregions, such as CMP, will exacerbate water stress, particularly during the dry season. According to their stomatal response, water stress-tolerant species have shown to be more successful at dealing with droughts in the Andean Páramo than water stress-avoiding species, suggesting that species with the first strategy would be more likely to adapt to climate change77. Similarly, experiments using open-top chambers in the Andes have shown changes in the plant’s taxonomic and growth form diversity, mainly by a progressive increment of lower elevation species of tussock grasses and shrubs and a reduction of rosettes78,79. Tree species and giant rosettes in HETEs will then be more susceptible to higher temperatures and lower precipitation than herbaceous and shrub species. We expect the CMP and the NAP to experience shifts in community structure and composition by increasing the dominance of herbaceous and shrub species with climate change22,76,77.

Differences in the thermal sensitivities and the dispersal capacities, among other traits at the specific level, will also produce changes at the community level, e.g., due to the disruption of biotic interactions through spatial and temporal mismatches in phenology and dispersal28,30,80,81,82. In addition, breaching baseline spaces toward novel hydroclimatic conditions could result in migration from lower elevations, inducing community changes or even generating novel ones45,57,83.

These changes in vegetation structure and composition can modify HETE functioning, impacting its hydrology and water regulation capacity. For instance, changes in the vegetation structure could alter the interception of fog and the contribution of occult or horizontal precipitation to the water balance of HETEs, which is up to ca. 30% of the precipitation inputs in Andean páramos84. In tropical montane cloud forests, cloud water interception can reach 5% to 75% of total precipitation85. Additionally, water yield for páramo ecosystems has been reported to be higher, with about 63% of rainfall compared to 57% for cloud forests and 42% for rainforests86,87. It has been reported that projected changes in hydroclimatic conditions will also impact cloud immersion, reducing the area of both tropical montane cloud forests and páramo in South America by up to 86% and 98%, respectively, with some ecoregions in northern South America, such as CMP, reaching 100% of projected area reduction9. Despite the difference in methodologies, our results also show a worrying impact on CMP, although the outlook for the rest of South America is more optimistic.

Changes in the dominance of vegetation growth forms resulting from the high vulnerability in the Neotropics, Afrotropics and Australasia could also alter evapotranspiration as vegetation exhibits different response strategies to avoid excessive water losses86. Since vegetation reduces soil humidity loss depending on their cover density and structure88, changes in vegetation cover can further impact the water yield89,90,91. Projected changes in the hydroclimatic spaces of HETEs will also directly affect their hydrology and capacity to supply water downstream. Increments in temperature and changes in precipitation patterns and intensity will increase evapotranspiration and modify water inputs to the ecosystem, altering the water balance of HETEs and their water storage capacity. For the specific cases of extreme and seasonal hydroclimatic spaces, our results project that drier seasons and higher temperatures and precipitation seasonality will impact the ability of HETEs to provide continuous and regular water flow downstream92. Together, these could affect the constant water requirements of cities and communities around these ecosystems92 and water availability for hydropower production and agriculture, thus risking socioeconomic development and food security93,94. Beyond water regulation, the provision of other valuable ecosystem services will be impacted by climate change among HETEs in the Neotropic13,32, Afrotropic62,95,96, and Australasia64.

One limitation of our framework of breaching baseline hydroclimatic spaces and vulnerability to climate change is that it does not consider the implications of land use change. Beyond vulnerability to climate change, HETEs are vulnerable to land use and land cover changes (LULC). For instance, productive activities such as floriculture and potato crops can benefit from Andean HETEs’ hydroclimatic conditions, which could increase interest in agricultural expansion97. This has largely contributed to the degradation, habitat loss, and fragmentation of HETEs in recent decades. Some studies have reported these anthropogenic impacts in the Afro-Alpine Belt, where the main drivers of LULC are linked to increased human population pressure in higher-elevation areas due to high population pressures in lower regions. This has led to natural vegetation degradation by land clearing for farmland, woodcutting, and livestock grazing. The absence of land use policy and climate variability also contribute to LULC in these areas25,27. In the Andes, the transformation of HETEs is also driven by agricultural expansion26,97,98,99, constraining the dispersal capacities of species by reducing ecological connectivity and threatens their ability to respond to climate change by moving to suitable climates28,29,100. It also impacts the water regulation capacity of HETEs by modifying the land cover and the soil properties with alterations in evaporation, runoff, and water seepage rates89,90,101. Due to climate change, farmers in and around HETEs may be forced to change agricultural practices and locations to track suitable climates upwards and maintain yields26,93,102. Such interaction between climate and land use changes can potentially exacerbate the vulnerability of HETEs to global change100,103,104, even beyond those found in this study. Incorporating land use changes and other stressors into the vulnerability analysis of HETEs could help improve the understanding of global change impacts on biodiversity in these ecosystems.

Our findings provide valuable spatially explicit information on the vulnerability of HETEs to climate change and allow for the overall comparison among ecoregions. This information is crucial for enhancing our ability to integrate climate change adaptation measures into policy development and management strategies and prioritize efforts to conserve these key ecosystems. For instance, knowledge of the extent and direction of hydroclimatic changes in HETEs provide criteria for a better selection and implementation of more suitable management strategies, accounting for the plausibility of these ecosystems to maintain their baseline biotic and abiotic features43,57.

The framework of vulnerability to climate change can also be used for other ecosystems, providing a valuable contribution to biogeography and conservation ecology. Nevertheless, even when we used a bilinear interpolation approach to mitigate the potential impacts of climate data spatial resolution on the definition of hydroclimatic spaces, the resolution of the climate data we employed could impact the accuracy of our modeling. Data with finer resolution can offer more detailed predictions on habitat loss and species distribution changes, particularly in topographically diverse regions. In contrast, coarse-resolution data are better suited for broader, regional analyses but may overlook important microhabitats and local variations105,106,107, such as topographically controlled climate variations crucial for certain species108.

Fine-resolution climate datasets are available for HETEs and have been used in previous studies. However, their accuracy in tropical mountain regions is questionable because of the scarcity of climate monitoring stations and data availability109. It is crucial to generate fine-resolution climate data for high-elevation ecosystems such as HETEs that account for the complex topography of those areas and allow for more detailed and accurate modeling. Integrated and multiscale monitoring of biodiversity and ecosystem services in HETEs is also key to improving our understanding of climate change’s impacts on biodiversity and the functioning of these ecosystems110. To that end, we need to strengthen the climate and hydrological monitoring network and other current monitoring initiatives in HETEs110,111,112 to reduce data and information deficiencies.

It is worth noting that our results show the potential implications of the effects of climate change on HETEs under the SSP585 scenario. Although these results can seem bleak, analyzing this business-as-usual scenario warns about the impacts of continuing current trends and policies without significant efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or mitigate climate change impacts. Accomplishing climatic goals and agreements is necessary to reduce these emissions and slow down the projected impacts of climate change on high-elevation ecosystems by changing the trajectory of climate change towards more optimistic scenarios.

Methods

Delimitation of humid high-elevation tropical ecoregions

We used the Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World (TEOW) dataset Version 2.056 by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) to delineate humid high-elevation tropical areas for subsequent spatial analyses. There, ecoregions are defined as land units that harbor particular assemblages of species, and their limits represent the original extent of the natural communities before anthropogenic transformation56. This dataset delineates the global terrestrial ecoregions based on the conciliation of previous studies and biogeographical classifications.

We filtered seven ecoregions from the TEOW dataset belonging to the Montane Grasslands and Shrublands biome. We followed the Humid Tropical Alpine Regions delimitation of11 which specifies that HETEs occur in the northern Andes, in the Afro-alpine belt, and New Guinea. We defined four ecoregions for the Neotropics: Santa Marta Páramo (SMP), Cordillera de Mérida Páramo (CMP), Northern Andean Páramo (NAP), and Cordillera Central Páramo (CCP); one ecoregion for Australasia: Central Range Sub-alpine Grasslands (CRSG) located above 3000 m above sea level (m.a.s.l.) of elevation19; and two ecoregions for the Afrotropics: East African Montane Moorlands (EAMM), and Ethiopian Montane Moorlands (EMM), which are located from 3000 m to over 4500 m.a.s.l18. It is worth noting that some authors report the extension of the Andean HETEs southwards to the north of Peru (approximately ~5°S, where the páramo ends and the ecosystem known as Jalca begins)11. In contrast, others consider that páramo extends even more to the South (approximately 10°S)113. As the TEOW dataset agrees with the latter and locates the CCP between approximately 5°S and 10°S56, we also include the CCP ecoregion in our analyses.

Climate data

We used downscaled climate raster data from the latest NASA Earth Exchange Global Daily Downscaled Projections archive for the CMIP6, NEX-GDDP-CMIP6, with a horizontal resolution of 0.25° ( ~ 25 km)55. Although the CMIP GCMs have shown to be reliable and, therefore, widely used for producing climatic projections, their outputs have coarse spatial resolutions ( ~ 100–200 km) that make them unsuitable for regional to local analyses114. However, GCM downscaling allows for data generation at finer temporal and spatial scales, which is more suitable for a broader range of applications where ecosystems with a narrow spatial extent are considered115. The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset was produced using a statistical downscaling algorithm that uses climate observations to adjust future climate projections to ~25 km spatial resolution55. While there are very high-resolution global climate datasets ( ~ 1 km) such as WorldClim116 and CHELSA117, we selected the medium-resolution NEX-GDDP-CMIP6, looking for a trade-off between resolution and accuracy, as the capacity of high-resolution datasets to accurately represent the climate in topographically complex regions, such as tropical mountains, has been largely questioned6,109,118. The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset has been used in climate change studies with various spatial and temporal scales and applications119,120,121,122.

The NEX-GDDP-CMIP6 dataset compiles climatic data for five experiments produced from several GCMs for the CMIP6. The historical experiment extends from 1950 to 2014, which is helpful as a climatic reference, while the four remaining experiments are based on the SSPs, consisting of different scenarios of future greenhouse gas emissions, land use changes, and radiative forcing levels covering the period 2015 to 2100123. The SSP585 is a high-emission climate change scenario representing the upper limit of feasible future climatic pathways, assuming continuous fossil-fuel development in the future and an 8.5 W/m2 level of forcing by 2100124. Continuing current trends and policies without successful efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or mitigate climate change impacts in a business-as-usual and worst-case pathway make SSP585 an ideal scenario to explore the potential outcomes of no climatic action on HETEs6,125. We focused on the historical and SSP585 experiments from six widely used GCMs (i.e., ACCESS-ESM1-5126, EC-EARTH3127, EC-EARTH3-Veg-LR127, HadGEM3-GC31-MM128, IPSL-CM6A-LR129, and MPI-ESM1-2-HR130) to compute model ensemble-based data for each of the seven HETE ecoregions. We estimated the means for the baseline 30-year period (1985–2014) and the future 30-year period (2071–2100)125. These GCMs have been used in previous assessments of global hydroclimatic change and have different original spatial resolutions before downscaling, in some cases, integrating land surface and dynamic vegetation models131.

Data processing

For each of the six GCMs and the two experiments selected for the analyses, we downloaded daily precipitation (P), daily minimum near-surface air temperature (Tmin), and daily maximum near-surface air temperature (Tmax) data from the NASA Center for Climate Simulation (NCCS) data collections. We limited the spatial extent of the climate data by selecting every raster cell intersecting the previously filtered high-elevation Tropical Ecoregions’ polygons from the TEOW dataset. Daily raster data were aggregated by cell to compute monthly climate time series for the baseline (1985–2014) and the future (2071-2100) 30-year periods. The Tmin and Tmax were averaged for every month and year. The daily P was aggregated to monthly precipitation (See next section). We then used the P, Tmin, and Tmax monthly time series to compute six selected bioclimatic variables (Table 1) using the biovars function from the dismo package in R132. The biovars function takes as inputs P, Tmin, and Tmax monthly raster data for a specific year (i.e., one raster for each variable per month) and returns a single raster for each bioclimatic variable for a particular year. Bioclimatic variables are often used as covariates in potential species distribution models. They summarize annual climatic conditions, seasonal mean conditions, and intra-annual seasonality, providing information relevant to analyzing the species’ response to climate changes due to ecological and physiological constraints133. We based the selection of the six bioclimatic variables on their importance for HETE functioning and their impact on animal and plant physiology52,53,54. Finally, we computed the six bioclimatic variables for every year and averaged their annual values across the baseline and future 30-year periods134. This procedure was repeated for each of the six GCMs.

Hydroclimatic changes in HETEs between 1985–2014 and 2071–2100

We refer to changes as the difference between the 30-year baseline and future values for each GCM. We used the spatial coverage of the seven ecoregions to extract spatial weighted means for the baseline, the future periods and their changes for every ecoregion. We used the pixel areas intersected by the ecoregion’s spatial coverage as weights (See Fig. S6). We averaged them to compute model-based ensemble means for each ecoregion and HETEs overall, and the standard errors among GCMs. The model-based ensemble mean is a widely used approach to combine multiple GCMs to produce more robust and accurate climatic estimations than using individual GCMs, as each GCM has its own biases and errors, and by averaging their outputs the ensemble mean reduces the impact of these individual inaccuracies135,136.

Baseline and projected hydroclimatic spaces

We used the 30-year means of the baseline period to build three 2-dimensional baseline hydroclimatic spaces for each ecoregion. The long-term (LT) baseline hydroclimatic space represents the annual climatic conditions and consists of the long-term means of T and P (Table 1). The extreme (EX) baseline hydroclimatic space corresponds to the extreme seasonal conditions and involves Tmw and Pd. The seasonality (SE) baseline hydroclimatic space denotes the intra-annual seasonality and consists of Ts and Ps. It is worth noting that HETEs have been previously found to be susceptible to the six variables comprising the three hydroclimatic spaces (LT, EX, and SE; Table 1), becoming critical environmental drivers of these ecosystems’ occurrence and persistence52,53,54.

Considering the spatial resolution of the data, we used bilinear spatial interpolation to obtain the baseline values of the variables (i.e., T, P, Tmw, Pd Ts, Ps) for each HETEs’ areas from the 30-year climatic mean rasters. By HETEs’ areas, we refer to the geometric intersections of the ecoregion’s spatial extents and the raster data pixels (See Fig. S6). The interpolated values were assigned to the centroid of every HETEs’ area, and later, we used them to compute the baseline hydroclimatic spaces as the 95% probability of 2-dimensional kernel densities. In this way, we reduced the potential noise of using cell values highly influenced by lower elevation areas, given the insular and fragmented distribution of HETEs. Due to the low number of pixels within the extent of the SMP ecoregion, we decided to merge them with the NAP pixels to build the hydroclimatic spaces. We repeated this for the future period to construct the three 2-dimensional projected hydroclimatic spaces.

Changes between current baseline and future hydroclimatic spaces

To quantify the trajectory of the changes in the hydroclimatic spaces (i.e., the change in LT, EX, and SE conditions in time), we computed the centroids of the baseline and projected hydroclimatic spaces and the vector resulting from their change in the 2-dimensional space131,137,138. We then described and summarized the trajectories through the direction of change (({{{rm{theta }}}})) as follows:

where θ is the direction of change in degrees from the x-axis (i.e., depending on the variables selected). The pairs of ∆y and ∆x become the ∆T and ∆P for LT, ∆Tmw and ∆Pd for EX and ∆Ts and ∆Ps for SE, respectively, as computed from the normalized change vectors. Conversely, the I is calculated as:

The severity of the movement (S) can be defined as the percentage of the area of the future hydroclimatic space that does not intercept the baseline one, i.e., the percentage of the extent of the HETEs in which baseline hydroclimatic conditions are breached. Hence, S becomes an indicator of the impacts of the direction and intensity of the movement on the ecoregions, as the changes in the projected hydroclimatic conditions are a combination of them. S was calculated as:

Where A is the area of the projected hydroclimatic space, and B is the area of the baseline hydroclimatic space.

Location and quantification of safe and breached hydroclimatic spaces

Hydroclimatic spaces were also used to locate the extension of the HETEs’ areas (i.e. the geometric intersections of the ecoregion spatial extents and the raster data grids) within each ecoregion that will either remain in their safe hydroclimatic spaces or be breached, according to their trajectories of change. To that end, we identified and quantified the HETEs’ areas whose projected future hydroclimatic values overlapped the baseline hydroclimatic spaces in the 2-dimensional space (see Fig. 3). When overlapping exists the HETEs’s areas were classified as safe, and those whose projected values did not overlap were classified as breached.

Furthermore, the breached HETEs’ areas were also reclassified by assessing if their projected future hydroclimatic values would overlap the baseline hydroclimatic space of any ecoregion. The HETEs’ areas whose projected future hydroclimatic values did not overlap the baseline hydroclimatic space of any of the seven ecoregions were classified as novel, as their hydroclimatic conditions would not have been experienced before by any ecoregion. If the HETEs’ areas were not classified as novel, we classified them as analog, because although the specific baseline hydroclimatic space of the ecoregion in question would be breached, their hydroclimatic conditions would still resemble baseline hydroclimatic conditions of other ecoregions.

We performed this classification for the three types of hydroclimatic space (i.e., LT, EX, and SE). Finally, we mapped and quantified the vulnerability to climate change of each ecoregion based on the data resulting from the number of breaches of the three types of hydroclimatic spaces. Then, we used four categories to determine the vulnerability of the HETEs’ areas to climate change according to their number of breached spaces. Areas of the HETEs with no breaching were assigned with low vulnerability; areas breaching one of the three types of hydroclimatic space were assigned with medium vulnerability; those breaching two of the three types of hydroclimatic spaces were assigned with high vulnerability; and areas breaching the three hydroclimatic spaces were assigned as critically vulnerable.

Responses