Customizable virus-like particles deliver CRISPR–Cas9 ribonucleoprotein for effective ocular neovascular and Huntington’s disease gene therapy

Main

Other research teams and ours have begun clinical trials of in vivo CRISPR delivery to treat inherited ocular and liver diseases and virus infection by using adeno-associated virus (AAV), lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and virus-like particles (VLPs) as the delivery tool, respectively1,2,3. Despite this progress, delivery restrictions remain to be addressed to enable targeted delivery of in vivo CRISPR therapeutics as editing in off-target cells can alter the cell fate of sub-populations or induce immune responses4,5,6.

Historically, the immune response has been tightly associated with the safety and efficacy of gene therapy7. Off-target delivery by vectors to antigen-presenting cells may activate innate immune sensing and induce strong adaptive immune responses, reducing the efficacy of in vivo gene therapy8,9,10,11. Studies have reported that more than 50% of the population is serum positive for Cas9-neutralizing antibodies and cytotoxic T cells12,13. Anti-Cas9 humoral and cellular immune response may result in death of the edited cells, which constantly express Cas9 (refs. 14,15). In contrast to DNA-based delivery, protein-based CRISPR delivery may offer minimal immunogenicity as Cas9 protein would only present for a short duration. Therefore, time-restricted, encapsidated and cell type-targeted CRISPR delivery is key to developing safe and effective in vivo gene editing therapeutics.

Owing to its transient nature, ribonucleoprotein (RNP) is an attractive source for CRISPR therapy16,17. However, its applications in vivo have been reported only in a few cases, wherein liposomes, gold nanoparticles and nanocapsules were used as delivery vectors, or naked cell-penetrating RNP was used directly18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25. These synthetic nanocarriers have to overcome the intracellular endosome barrier, while naked RNP may encounter pre-existing anti-Cas9 antibodies in vivo16,26. Moreover, the organic molecules in the synthetic nanoparticle components can be toxic and inflammatory27. Essentially, the existing RNP delivery strategies have not been able to mediate cell-specific gene editing.

To overcome the limitations of synthetic nanomaterials, the author and other groups investigated biosynthetic VLPs derived from lentiviral vectors (LVs) for their application in delivering zinc-finger nucleases, transcription activator-like (TAL) effector nucleases and I-SceI in the format of protein, and showed proof of concept that time- and quantity-restricted exposure was sufficient to mediate genomic engineering28,29,30. As CRISPR has emerged as the mainstream genome editor owing to both simplicity and efficiency, lentiviral and retroviral VLPs were engineered to deliver CRISPR using distinct mechanisms for cargo incorporation such as direct Cas9 protein fusion to GagPol31, RNP via aptamer-modified guide RNA32 or Cas9-Gag/GagPol fusion33,34,35, or cargo RNA via MS2 stem loop-modified messenger RNA/gRNA36,37,38 and Peg10’s untranslated region-flanking mRNA39; however, so far, the successes were mainly in in vitro studies likely owing to compromised VLP titre or suboptimized efficiency. Despite that we and others have shown a few examples of successful in vivo editing with VLP, all of them are based on non-targeted delivery33,34,37,38. Therefore, VLP technologies for cell-targeted gene editing in vivo are yet to be developed, and their therapeutic and post-therapeutic effects in the disease models need to be demonstrated or characterized before clinical translation.

Here we engineered lentiviral Gag, gRNA and VLP surfaces for ribonucleoprotein delivery (designated as RIDE) and achieved efficient and cell type-specific in vivo gene editing. Using RIDE, we achieved therapeutic efficacy in mouse models for both ocular neovascular and Huntington’s diseases. In addition, the efficiency and safety of RIDE were confirmed in non-human primates (NHPs) and Huntington’s disease patients’ induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived neurons. As a cell-tropism programmable RNP delivery platform, RIDE may accelerate the development of in vivo CRISPR therapeutics for broad applications.

Building up and characterizing CRISPR RNP-carrying VLPs

To enable CRISPR RNP delivery, we first inserted two copies of the MS2 stem loop into the gRNA backbone in positions extruded from the Cas9–gRNA complex and hypothesized that the stem loop-incorporated gRNA would assemble with Cas9 to RNP and piggyback the Cas9 protein into VLPs via the specific interaction between the stem loop and MS2-coat modified Gag (Fig. 1a). The gene editing efficiency of modified gRNA was comparable to that of the original gRNA when transferred by plasmid transfection in 293T cells (Fig. 1b). However, when packaged into VLPs and co-transduced with the Cas9 mRNA-carrying lentiviral particle (mLP)38, the activity of modified gRNA was significantly impaired compared with the integrase-deficient lentiviral vector (IDLV)-expressed gRNA32,36,40 (Fig. 1c). Therefore, we included Cas9 in the process of VLP production by supplementing wild-type (WT) GagPol-D64V to encapsidate the pre-assembled gRNA–Cas9 complex, thereby generating VLPs for CRISPR RNP delivery (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1).

a, Design of a gRNA-encoding plasmid, which transcribes a gRNA-containing MS2 stem loop. b, Comparison of the efficiency of gene editing mediated by MS2 stem loop-containing gRNA (gRNA-MS2in) and normal gRNA. gRNA (2 µg) and lentiCas9-Blast (2 µg) plasmids were co-transfected into 2 × 105 293T cells. c, The frequency of indel mediated by gRNA-carrying VLP. gRNA-incorporated VLP or IDLV-gRNA (10 µl) was co-transduced into 2 × 104 293T cells with 10 µl mLP-Cas9. Crude VLP and IDLV were concentrated 300 times. RIDE-gRNA versus IDLV-gRNA, ***P = 0.0003. d, Schematic illustration of RIDE production. Indel frequency was analysed by TIDE software. e, Immunostaining of Cas9 in RIDE-transduced 293T cells 1 h, 24 h and 48 h post-transduction. p24 RIDE (200 ng) was transduced into 6 × 104 293T cells. The dashed box represents the enlarged area. Scale bars, 100 μm (front images) and 30 μm (enlarged images). Four images were acquired for each group. f, Western blot analysis of the mechanism of Cas9 incorporation and delivery. The experiment was performed twice with similar results. g, Representative TEM images for RIDE-CRISPR and Lenti-CRISPR. Scale bar, 200 μm. Four images were taken for each group. h, Gene editing efficiency of RIDE in different cell types. p24 RIDE (100 ng) was transduced into 2 × 104 cells. i, Comparative analysis of off-target activity by AAVS1-targeting RIDE and Lenti-CRISPR. RIDE or LVs (50 ng p24) were transduced to 2 × 104 293T cells seeded 24 h before transduction. *P = 0.0294 and *P = 0.0334 for RIDE versus Lenti-CRISPR on Off-6 and Off-8, respectively. Data and error bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. from three biologically independent replicates. Unpaired one-tailed Student’s t-tests were applied. NS, not significant.

Source data

To verify whether Cas9 proteins were truly incorporated into VLPs, we stained particles and observed evident co-localization of Cas9 and the capsid protein p24 (Supplementary Fig. 2). We then transduced VLPs into 293T cells and found that the Cas9 protein co-localized with p24 1 h post-transduction, suggesting that the entry of RNP was via VLPs (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 3). Interestingly, at 48 h post-transduction, the co-localization nearly disappeared, which may be due to the rapid turnover of p24 and Cas9 proteins or their relocation (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 4). To investigate the packaging mechanism, VLPs were produced with variables, including VSV-G, gRNA and GagPol. We found that Cas9 was efficiently packaged only in the co-presence of the MS2 coat protein and MS2 stem loop, indicating the specificity of RNP delivery (Fig. 1f). In addition, successful RNP delivery into cells was dependent on VSV-G (Fig. 1f). While the WT GagPol was not necessary for Cas9 packaging, it enhanced the yield of VLPs in terms of p24 (Fig. 1f). Under an electron microscope, the structure and size of RNP-carrying RIDE were similar to those of the traditional LV (Fig. 1g). Notably, in a time-course study for Cas9 expression, we found that the protein was hardly detectable in 293T cells 72 h after transduction (Extended Data Fig. 1).

Next, we investigated the editing efficiency of RIDE by comparing the non-viral and viral vectors. We found that RIDE was highly efficient across different endogenous genome loci in a variety of cell types (Fig. 1h). Moreover, RIDE was even more efficient than mLP to most loci, and the LNP-delivered RNP; in fact, its efficiency was comparable to that of LVs, although it was locus dependent (Extended Data Fig. 1). Notably, RIDE had comparable yields to conventional IDLV and induced fewer off-target effects than LV, which had long-term nuclease activity (Fig. 1i and Extended Data Fig. 1). In addition, the RIDE system was able to deliver the base editor with an efficiency of up to 69% (refs. 41,42,43) (Supplementary Fig. 5).

To determine the innate immune properties of RIDE, we used the cell line THP-1-derived macrophages, a simplified model of human macrophages, and found that RIDE did not induce IFNB1, ISG15 or RIG-I expression (Extended Data Fig. 2). When we injected Lenti-CRISPR into footpads, we found significant elicitation of anti-Cas9 and anti-p24 immunoglobulin G (IgG) in the sera of mice (Extended Data Fig. 2). By contrast, the elicitation of Cas9-specific IgG was not evident after RIDE treatment, although p24-specific IgG was significantly enhanced (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Gene editing therapy of retinal vascular disease in mice

Vascular endothelial growth factor-A (VEGF-A) is an important mediator of retinal vascular diseases44. Most anti-angiogenic therapies do not affect intracellular targets and, consequently, do not distinguish pathologic from physiologic cellular sources45. Both the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) and Müller cells are major VEGF-A producers in the eyes46. However, the knockdown of VEGF-A in Müller cells exerts harmful effects on photoreceptors4.

We and other researchers have noticed that VSV-G-pseudotyped LV specifically targets the RPE in adult mice when injected subretinally, owing to the highly active phagocytosis in the RPE and the physical barrier function of the interphotoreceptor matrix38,47,48. Likewise, RPE tropism was also confirmed for GFP-labelled RIDE (Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, we pseudotyped Vegfa-targeting RIDE with VSV-G and evaluated its therapeutic potential in a laser-induced mouse model of retinal vascular disease (Fig. 2a). We first analysed the on- and off-target effects of RIDE in the RPE in vivo after subretinal injection (Fig. 2b), which showed 38% indel frequency on the Vegfa locus without detectable off-target effects on the top-ranked off-target sites (Fig. 2c). Accordingly, an approximate 60% decrease in the VEGF-A levels was detected in the RPE/choroid/scleral tissues (Fig. 2d).

a, Experimental workflow. b, Schematic diagram of subretinal injection. c, Deep-sequencing analysis of the on-target (On) and off-target (OT) effects of the Vegfa-targeting RIDE in RPE cells in vivo. n = 1 mouse. d, ELISA of VEGF-A levels in the RPE/choroid/scleral (RCS) complex. n = 9 mice. PBS versus RIDE, **P = 0.0023. e, Representative laser-induced CNV areas in IB4-stained choroidal flat mounts of mouse eyes injected with RIDE or PBS. The white arrowheads indicate the position of the optic disc. The dashed white circles delineate the CNV region. Scale bar, 200 μm. f, Analysis of the CNV areas in five mice 7 days after laser treatment using IB4-stained choroidal flat mounts. A total of 100 ng p24 RIDE was administered into each eye. n = 18 CNV areas, PBS versus RIDE, *P = 0.0254. g, Representative trace of the a- and b-wave amplitudes in the presence of a scotopic-adapted 3.0 Hz stimulus. h,i, Quantitative analysis of a-wave (h) and b-wave (i) (n = 5 mice). j, Visualization of the 22 identified clusters using two-dimensional tSNE. PCA of 19,079 single-cell expression profiles was obtained from the RPE layers of the PBS, RIDE and empty VLP groups (four mice from each group). A total of 100 ng p24 RIDE or VLP was injected subretinally. k, Determination and clustering of cell types according to the average expression of known marker genes for each cluster. Violin plots of gene expression are shown alongside the dendrogram. l, Cell composition distribution in the RPE tissue after different treatments. Data and error bars represent the mean ± s.e.m. Paired two-tailed Student’s t-tests for d and unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests for f. Two-way ANOVAs for h and i.

Source data

IB4 staining of the RPE-choroid lamination further revealed that the area of choroidal neovascularization (CNV) in the treated group was decreased by 43% (n = 18 CNV areas; P = 0.0254, Student’s t-test; Fig. 2e,f). To investigate CNV in vivo, we used optical coherence tomography (OCT) to assess the anatomical appearance of lesions and structural integrity. The subretinal fibrovascular complex of CNV was identified as a hyperreflective region in OCT slice images. OCT images were collected 7 days after laser photocoagulation, which showed that the CNV area was noticeably reduced in the RIDE groups (Supplementary Fig. 7).

To evaluate the ocular tolerability and safety of RIDE, both eyes were subjected to 0.003–10 cd s m−2 flash stimulation by electroretinography (ERG). The amplitudes of a- and b-waves in CRISPR-treated eyes did not decrease compared with the control eyes, indicating that RIDE did not cause observable electrophysiological function impairment (P > 0.05; n = 5 mice; Fig. 2g–i).

It remains unknown whether the delivery of CRISPR induces editing-specific cell state changes. We therefore characterized the single-cell RNA transcriptome of the RPE after CRISPR administration. We treated mice with RIDE, empty VLPs or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by subretinal injection and isolated the RPE layers for single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) after 7 days. To reduce data contingency, eight treated eyes from four mice were combined in each group (Supplementary Table 1).

We obtained transcriptomic profiles for 19,079 cells, of which 5,745, 6,257 and 7,077 cells originated from the PBS, RIDE and empty VLP groups, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). We identified 22 cell types or states, among which 8 were detected as RPE cells (Fig. 2j). We further determined and clustered the cell types according to the average expression of known marker genes from each cluster (Fig. 2k and Supplementary Table 3). Strikingly, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) characteristics were detected primarily in the RIDE group (8.28%) (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Table 2). The RPE cells were further subdivided into 11 cell states (Supplementary Fig. 8a), and EMT was found in 25.94%, 7.34% and 0% of the total RPE in the RIDE, empty VLP and PBS groups, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8b and Supplementary Table 4).

While immune cells were rarely detected in the PBS group, samples from the RIDE and empty VLP groups contained almost all immune cell subsets with an overall dominance of macrophages (Fig. 2l and Supplementary Table 2). The cell type compositions of the RIDE and empty VLP groups were substantially similar in terms of T cells (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 5) and dendritic cells (Supplementary Fig. 10 and Supplementary Table 6). Macrophages subdivided into 10 clusters showed few differences in gene expression between the RIDE and empty VLP groups; however, the RIDE group showed a high level of gene expression from clusters 0 and 5 (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Table 7). We also investigated the short-term apoptosis status of the RPE and EMT and did not find a clear difference between the RIDE, empty VLP and PBS groups (Supplementary Fig. 12).

In addition, we dissected the retina, which was almost untargeted by VLP, and performed the scRNA-seq 7 days after treatments. In contrast to the PBS group, the immune cell infiltration was evident in both empty VLP and RIDE-treated eyes after subretinal injection, echoing the results in the RPE layer (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14, and Supplementary Tables 8–13). Interestingly, natural killer (NK) cells, which were trivial in the RPE layer, enriched in the retina after VLP treatment. Overall, our results showed that immune responses could be triggered in the ‘immune privilege’ eyes shortly after gene therapy, suggesting the importance of transient delivery of gene editing enzymes.

Subsequently, we examined the long-term safety of RIDE in vivo (Fig. 3a). OCT (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 15) and ERG tests (Fig. 3c–e) showed no significant differences between the two eyes 7 months after treatment with and without RIDE. We also performed terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labelling (TUNEL) staining to detect whether RIDE induced apoptosis in retinal cells. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, the TUNEL-positive cells were widespread in the control group with acute ischaemic injury in the retina but were undetectable in the RIDE group, indicating the absence of apoptotic cells in the retina after gene editing in the long run.

a, Flowchart for the long-term (7 months) effects of RIDE. b, OCT was used to evaluate RIDE-induced damage in each group. The dot box area was enlarged and placed on the right side. ONL, outer nuclear layer; ELM, external limiting membrane; RPE, retinal pigment epithelium. n = 3 mice. Scale bars, 200 μm (left) and 100 μm (right). c, Representative trace analysis of a- and b-waves in the presence of a scotopic-adapted 3.0 Hz stimulus. d,e, Quantitative analysis of a-wave (d) and b-wave (e) in both the PBS and RIDE groups (n = 7 mice). Data and error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. Two-way ANOVA.

Source data

Reprogramming the cell tropism of RIDE

To evaluate whether RIDE could be retargeted to specific cell types, we pseudotyped RIDE with a CD3-recognizing envelope, a modified Nipah virus glycoprotein redirected by a single-chain antibody. We found that the editing efficiency of the CD3-modified RIDE was significantly higher in the CD3+ population than in the unsorted and CD3− populations, whereas that of VSV-G-pseudotyped RIDE was not different among different cell populations (Supplementary Fig. 17a). Similarly, when pseudotyped with an engineered DC-SIGN-recognizing Sindbis virus glycoprotein (SV-G)49, RIDE preferably edited the dendritic cells with an efficiency even higher than that of the VSV-G-pseudotyped counterpart (Supplementary Fig. 17b).

To target RIDE specifically to neurons, we constructed a hybrid envelope protein (namely hyRV-G) by fusing human IgE signal peptide, the extracellular and transmembrane domains of the neuron-tropic rabies virus glycoprotein, and the cytoplasmic part of VSV-G50,51 (Extended Data Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 18). We found that the hyRV-G-pseudotyped IDLV was inefficient in transducing non-neuronal cells but as efficient as VSV-G in transducing SH-SY5Y—a human neuroblastoma cell line—demonstrating its neuron tropism in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 3b). To verify its neuron tropism in vivo, we injected a hyRV-G-enveloped GFP-encoding IDLV into the striatum of C57BL/6J mice and found that the majority of GFP signal was enriched in the neurons instead of microglia and astrocytes (Extended Data Fig. 3c,d and Supplementary Fig. 19). Therefore, we decided to pseudotype RIDE with hyRV-G for neuron-specific gene editing in vivo.

Huntington’s disease therapy in mice and NHPs

To visualize the in vivo distribution of hyRV-G-pseudotyped RIDE in the brain, we introduced RIDE containing a single gRNA targeting the WT mouse Htt gene (RIDE-Htt) and a lentiviral RNA-encoded GFP and performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining 1 month after stereotaxic injection in the striatum (Fig. 4a). We found the GFP-labelled RIDE in about half of the striatum, with a small amount leaked into the surrounding regions (Fig. 4b,c).

a, Schematic illustration of IHC and H&E analysis of RIDE distribution and tissue health in the brains of mice. RIDE labelled by a GFP-encoding viral cassette (RIDE-Htt-GFP) was injected into the right striatum of the adult C57BL/6 mice at a dose of 125 ng p24. After 30 days, mice were killed and their brain tissues were collected for analysis. b,c, Distribution of RIDE-Htt-GFP in the mouse brain by immunohistochemistry analysis. The left striatum was non-injected. n = 1. The area of the black box in the whole brain (b) was enlarged and placed on the right (c). Scale bars, 1,000 μm (b), 200 μm (c, above) or 50 μm (c, below). d,e, Whole brain tissue analysis with H&E. n = 1. The area of the black box in the whole brain (d) was enlarged and placed on the right (e). Scale bars, 1,000 μm (d), 200 μm (e, above) or 100 μm (e, below). The area of the white box (c, above) is enlarged and placed at the bottom (c, below).

Source data

Next, we performed deep sequencing of the striatum samples 7 days after RIDE injection and revealed that the highest indel frequency was only 2.4% (average 1.45%; *P = 0.0271; n = 4 mice; Extended Data Fig. 4a,b). We reasoned that the low indel frequency reflected the specific gene editing in neurons as the striatum was composed of various non-neuronal cell types, including astrocytes, microglia and infiltrating immune cells, all of which were enriched after injection (Supplementary Fig. 20). To test this speculation, we injected mice with GFP-labelled RIDE and sorted the GFP+ cells for third-generation sequencing. Indeed, we found enhanced readout of gene editing as shown by a unique large deletion spanning 2,201 bp, which accounted for 7.09% of the total reads (Supplementary Table 14). In addition, we performed western blotting, which confirmed the downregulation in HTT expression 14 days after RIDE treatment (Extended Data Fig. 4c). In addition, we compared RIDE and LNP-delivered CRISPR/RNP and found that both the VSV-G- and hyRV-G-pseudotyped RIDE outperformed LNP-delivered CRISPR/RNP in downregulating HTT expression in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 21). To visualize the neuron status after treatment, we stained the striatum with the neuron-specific marker NeuN. Although we found linear gathering of the nuclei in some of the treated mice, the traces were specifically restricted to the injection route (Fig. 4d,e and Extended Data Fig. 4d), suggesting that the loss of HTT expression in the striatum was unlikely due to neuronal death.

To evaluate the long-term consequences of HTT inactivation in vivo, we injected RIDE (21.5 ng p24 per side) or PBS into both sides of the striatum in C57BL/6 mice aged 2 months (n = 6 per group) and found that RIDE caused neither abnormal behaviour in the 110 days follow-up nor body weight loss 8 months after treatment (Extended Data Fig. 5).

Next, we found that even the research-grade RIDE did not provoke type I interferon response in the brain, although it tended to elicit type II interferon response and the downstream Cxcl9 and Cxcl10 expression (Extended Data Fig. 6). Notably, the type II interferon response was likely due to the genomic or plasmid DNA carryover from the production process as we further found that it could be circumvented using Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-like grade VLPs (Extended Data Fig. 6). Taken together, RIDE could be tailored to target specific cell types, enabling efficient and safe in vivo gene editing.

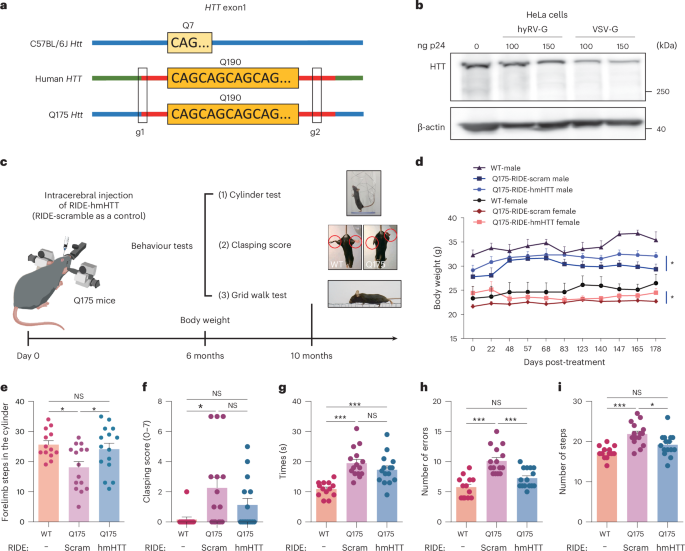

To test the efficacy of CRISPR-mediated human mutant HTT (hmHTT) inactivation, we dosed RIDE in heterozygous Q175 mice in which the exon 1 of the endogenous Htt was replaced by exon 1 of hmHTT with ~190 CAG repeats. To delete the polyQ domain of hmHTT, we designed five gRNAs (g1–5) flanking the CAG repeat in exon 1 of hmHTT and found strong activities for g1 and g2 gRNA combinations (Extended Data Fig. 7a,b). Therefore, we chose g1 and g2 combinations to produce RIDE-hmHTT for our subsequent studies (Fig. 5a). First, we analysed HTT expression using western blot and found that the VSV-G-pseudotyped RIDE, but not the hyRV-G-pseudotyped RIDE, efficiently reduced HTT expression in HeLa cells (Fig. 5b). In addition, the HTT knockout was confirmed with different HTT antibodies both in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 22). Moreover, we evaluated the RIDE-caused gene editing events using third-generation sequencing. Interestingly, we found that a 128 bp deletion was the dominant modification, accounting for 25.54% of all events (Supplementary Table 15).

a, Illustration of gRNA pairs designed to delete the polyQ repeats in the first exon of the HTT gene. b, Western blot analysis of the downregulation of HTT expression by RIDE in HeLa cells. RIDE was pseudotyped with hyRV-G or VSV-G. A representative result is shown from two biologically independent replicates. c, Schematic illustration of the behaviour study. Q175 mice were injected with RIDE-hmHTT (680 ng p24/both sides of the striatum), n = 15 mice (9 males and 6 females); or RIDE-scramble (680 ng p24/both sides of the striatum), n = 15 mice (7 males and 8 females). WT C57BL/6J mice were included as healthy control, n = 13 mice (6 males and 7 females). After 10 months, the behaviour tests were performed. d, Body weight changes of Q175 and WT mice 6 months after RIDE injection. Unpaired one-sided nonparametric test analysis. RIDE-hmHTT versus RIDE-scramble male mice, *P = 0.0281; RIDE-hmHTT versus RIDE-scramble female mice, *P = 0.0406. e, Mice were subjected to the cylinder test. WT mice versus RIDE-scramble Q175, *P = 0.0182; RIDE-hmHTT versus RIDE-scramble, *P = 0.0408. f, Clasping test. WT mice versus RIDE-scramble Q175, *P = 0.0157. g–i, Grid walk test. Times (g), WT mice versus RIDE-hmHTT Q175, ***P = 0.0009; WT mice versus RIDE-scramble Q175, ***P < 0.0001; errors (h), WT mice versus RIDE-scramble Q175, ***P = 0.0004; RIDE-hmHTT versus RIDE-scramble, ***P < 0.0001; steps (i), WT mice versus RIDE-scramble Q175, ***P < 0.0001; RIDE-hmHTT versus RIDE-scramble, *P = 0.0152. Data represent the mean ± s.e.m. A one-way ANOVA was applied.

Source data

Next, we injected hyRV-G-pseudotyped RIDE into both sides of the striatum in heterozygous Q175 mice aged 2 months to evaluate changes in their body weight and study their behaviour (Fig. 5c). First, we found that the Q175 mice treated with RIDE-hmHTT had significantly more body weight than the scramble RIDE-treated control mice 6 months after treatment (Fig. 5d). Next, we performed the cylinder test analysis for WT and RIDE-treated Q175 mice and recorded the number of times that the mouse reared to explore the cylinder and placed either the left or the right forepaw on the wall of the cylinder. We found that the RIDE-hmHTT-treated Q175 mice showed significant improvements in terms of forelimb steps in the cylinder (Fig. 5e).

In addition, we subjected these mice to the clasping and grid walk test. A common dysfunction demonstrated in the Q175 model is progressive limb clasping triggered by a tail suspension test. The scramble-treated Q175 mice showed significantly increased dystonic postures of hind limbs with self-clasping compared with the WT mice; this increase in RIDE-hmHTT-treated mice was nonsignificant (Fig. 5f). In the grid walk test, although the time required for crossing the grid tended to decrease in RIDE-hmHTT-treated mice (Fig. 5g), both the errors (foot slips) and steps were also significantly reduced compared with the scramble-treated Q175 mice (Fig. 5h,i). A parallel study with a shorter follow-up and a smaller sample size also showed similar results (Supplementary Fig. 23).

To determine whether RIDE was safe for future human application, we performed a safety study in NHPs (Fig. 6a). We used magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to facilitate injection and took images before and 3 weeks after treatment, which showed no detectable brain damage (Fig. 6b). To evaluate whether RIDE could downregulate HTT expression in NHPs, we performed western blot analysis of the putamen sample from one representative NHP, which showed that HTT expression was decreased in the RIDE injection side compared with the PBS injection side (Fig. 6c).

a, Experimental workflow for the NHP study. The left putamen of NHPs was injected with PBS and the right putamen was injected with HTT-targeting RIDE. b, Brain MRI images taken before and after treatment. Pre-injection: repetition time (TR) = 2,100 ms, echo time (TE) = 3.3 ms, slice thickness = 1.0 mm, 104 slices. 21 days: TR = 6,000 ms, TE = 98 ms, slice thickness = 3.0 mm, 16 slices. c, Western blot analysis of HTT expression 21 days after RIDE injection. A representative result is shown from two biologically independent replicates. d–i, Analysis of immuno-related gene IL-6 (d), IL-1β (e), interferon-γ (IFN-γ) (f), IL-4 (g), IL-23 (h) and macrophage inflammatory protein-1α (MIP-1α) (i) expression by RT–qPCR. n = 9 NHP putamen samples collected 21 days after injection (three punches from each putamen) (n = 8 for RIDE group in g). j,k, Liver function tests. Sera were collected before injection and 21 days after injection. The serum ALT levels (j) and serum AST levels (k). n = 3 NHPs. Data and error bars represent mean ± s.e.m. Paired two-tailed Student’s t-tests.

In addition, we collected putamen samples from both hemispheres 21 days after injection and analysed the expression of immune-related genes by RT–qPCR. Among the six cytokines analysed, we found that only interleukin-6 (IL-6) and interleukin-1β (IL-1β) expression was slightly increased in the RIDE injection sides (Fig. 6d–i). Next, we collected the sera before injection and 1, 14 and 21 days after injection to evaluate whether RIDE injection would cause liver damage. We found that neither the serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels nor the serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels changed significantly (Fig. 6j,k). Together, these results suggest that RIDE did not cause systematic risk in the NHPs.

On- and off-target gene editing in patients’ iPSC neurons

As the efficiency and specificity of genome editing may differ across species, we next evaluated the CRISPR delivery using RIDE in human neurons generated from Huntington’s disease patients’ iPSCs. We used RIDE carrying g1-gRNA and VSV-G pseudotype in this study to simplify analysis. Cells were collected 11 days post-treatment and on-target editing was analysed using amplicon sequencing (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). We observed efficient editing at the HTT locus up to 39% indels detected at the highest dose tested (Extended Data Fig. 8c).

A major safety concern with CRISPR-based therapies is unintended off-target editing. Therefore, we identified the potential off-target sites of g1-gRNA in the human genome using Cas-OFFinder52. Next, we performed multiplexed targeted deep sequencing on the predicted off-target sites using rhAmpSeq (IDT)53 (Extended Data Fig. 8d and Supplementary Data 1). A total of 369 sites were included in the panel. Twenty-four of these sites were either not compatible with multiplexed rhAmp PCR or yielded less than 2,000 sequencing reads, and were therefore excluded from the analysis. Among the 345 sites that were successfully sequenced, we found Cas9-induced indels only at one intergenic site with a low frequency of 0.5% (Extended Data Fig. 8e), suggesting that RIDE could achieve efficient editing with a favourable off-target profile in the human neurons.

Conclusion

RIDE assembles CRISPR RNP and VLP into one complex and is customizable for specific target cells. We showed cell-specific targeting with RIDE by taking advantage of the local tissue environment or engineered envelope proteins. We also revealed the impact of VLP on tissues and in vivo immune responses to VLP at the single-cell level. Long-term follow-up in mice and the NHP study showed that VLP was tolerated in vivo. In addition, RIDE had production yields comparable to the traditional LV. These features and findings are essential for the clinical translation of CRISPR.

VLP has recently gained new momentum as a delivery tool given the development of endogenous retrovirus or murine leukaemia virus-derived VLPs, namely SEND and eVLP, respectively39,43. Theoretically, SEND should not trigger immune responses as it is composed of human proteins that are tolerated by the human body through selective immune mechanisms, although this still warrants further verifications in clinical trials54. In our study, we consistently demonstrated that RIDE was inefficient in eliciting type I interferon response. However, we indeed detected anti-p24 antibodies. Surprisingly, in contrast to LV-delivered CRISPR, anti-Cas9 IgG was not elicited by RIDE.

Eyes and brains are usually considered immune-privileged55. However, we found that gene therapy vectors caused changes of the immune microenvironment in the eyes and induced infiltration of a variety of immune cells. Using scRNA-seq, we also defined the cell state transition to which gene editing may at least partially contribute by detecting an evident population of RPE cells with EMT characteristics56. These data emphasize that immune response and cell state changes should be taken into serious consideration during CRISPR gene therapy.

Targeted delivery is essential to improve the safety and efficacy of CRISPR therapeutics. Our study exemplified the therapeutic potential of RIDE in retinal vascular disease and Huntington’s disease models via localized delivery. Meanwhile, we speculate that RIDE can further be expanded to systematic delivery. Indeed, while our paper was under review, Hamilton et al. reported targeted genome editing in T cells in humanized mice57. RIDE, on the one hand, could be retargeted by taking advantage of the natural virus tropism58. More attractively, the specificity of RIDE may be customized for any cell type in combination with single-chain antibodies and DARPin technologies59,60,61 (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Methods

See Supplementary Information for more methods.

Plasmids

pCMV-2NLS-Cas9 expresses Cas9 driven by a CMV promoter. phCMV-ABEmax (or phCMV-BE4max) expresses ABEmax (or BE4max) driven by an enhanced CMV promoter. pU6-gRNA-MS2in contains the U6 promoter and a gRNA sequence inserted with two copies of the MS2 stem loop in the backbone. pU6-Osp.gRNA-MS2in is similar to pU6-gRNA-MS2in, except for the optimized gRNA backbone. The gRNAs were inserted into BsmBI-digested pU6-Osp.gRNA-MS2in. pCMV-hyRV-G encodes a rabies virus-derived envelope glycoprotein. All of the plasmids constructed in this study will be available through Addgene.

Cell and tissue cultures

Primary fibroblast cells from crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis) and 293T, NIH3T3, Cos7, SH-SY5Y, HeLa, HEB, HS683 and primary mouse glial cells were cultured in DMEM (Gibco). THP-1 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco) and differentiated into macrophage-like cells by treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (150 nM) (Sigma) before the experiment to boost cytokine production. The media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 2 mM l-glutamine (Gibco), 100 U ml−1 penicillin and 100 µg ml−1 streptomycin (Gibco). All cells were cultured at 37 °C and 5% (v/v) CO2.

Western blotting

To detect the production of Cas9, RIDE-CRISPR, RIDE-ABEmax, RIDE-BE4max or cell samples were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beyotime Biotechnology) in the presence of a protease inhibitor (Beyotime Biotechnology). The proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis before being transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (0.45 µm, Millipore) through a Mini Trans-Blot system (Bio-Rad). Membranes were blocked with 5% fat-free milk in Tris-buffered saline/0.05% Tween-20 for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were incubated with primary anti-Cas9 antibody overnight at 4 °C followed by incubation with anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:3,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #7076) or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (1:3,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #7074P2) according to species specificity of primary antibody for 1 h at room temperature. Protein signals were captured using a gel imaging system (Amersham ImageQuant 680, GE). Cas9 was detected using a Cas9 monoclonal antibody (mAb) (1:3,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #14697), β-actin was detected using a β-actin mAb (1:3,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #3700), and p24 was detected using an HIV-1 p24 mAb (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-69728) for normalization. HTT was detected using HTT-HDC8A4 mAb (1:2,000, Thermo Fisher, #MA1-82100), HTT-3E10 mAb (1:2,000, Santa Cruz, #sc-47757), HTT-MW1 mAb (1:3,000, Sigma-Aldrich, #MABN2427) and HTT-2166 mAb (1:2,000, Sigma-Aldrich, #MAB2166).

To detect Cas9 in the VLP, 10 µl ultracentrifuged supernatants (concentrated 300 times) were used directly for western blotting. To detect RNP transferred intracellularly, 30 µl ultracentrifuged supernatants (concentrated 300 times) were transduced into 2 × 105 293T cells seeded 24 h before transduction. To detect the HTT expression after RIDE or LNP-CRISPR treatment in mice, striatum tissues were dissected 7 days after stereotaxic injection and subjected to western blotting. HTT was detected using a mouse anti-huntingtin antibody (1:1,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, #sc-47757) followed by incubation with anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:3,000, Proteintech, #SA00001-1). Mouse β-actin (1:5,000, Proteintech, #66009-1-lg) served as an internal loading control. Full images of the western blots are shown in Source Data files and Supplementary Figs. 24 and 25.

Animals

Animal experiments were conducted at Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat Hospital Affiliated with Fudan University. The animal care, experimental and treatment procedures used in this study followed the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of each institute and were in accordance with the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology statement on animal testing. SPF-grade male C57BL/6J mice (6 weeks old, 18–22 g) purchased from Charles River Laboratories Animals were used in this study. Heterozygous Q175 knock-in mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (catalogue number 027410). RIDE or Lenti-CRISPR (1 µg p24) was injected into the footpads of the mice for IgG analysis. At the age of 8 weeks, RIDE-HTT (45 ng p24 per side) or Cas9/gRNA RNP in Lipofectamine 2000 was delivered to the striatum of Q175 mice using stereotaxic injection. For the delivery of Cas9 and gRNA complexes, 1 μl of 200 μM Cas9 protein was mixed with 2 μl of 50 μM gRNA and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, followed by mixing with 3 μl Lipofectamine 2000 and incubating for an additional 30 min.

The mice were kept in a room with a controlled environment (22 °C ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 40–70%, 12 h light/dark cycle) and provided with adequate food and drinking water. Similarly, adult C57BL/6J mice (WT) were anaesthetized using a combination of ketamine and xylazine (100 mg kg−1 and 10 mg kg−1, respectively) administrated intraperitoneally. Two microlitres of RIDE-HTT (21.5 ng p24) or IDLV-GFP (21.5 ng p24) with hyRV-G pseudotype was injected intracranially into the right or bilateral striatum (2 mm lateral and 0.5 mm rostral to the bregma at 3 mm depth) using a Hamilton microsyringe.

Healthy crab-eating macaques (Macaca fascicularis) aged 4–12 years were included in the experiment. The experimental operation procedures were performed in PharmaLegacy Laboratories following the approval of the Biology Laboratory Animal Management and Use Committee of PharmaLegacy (project number PL22-0802). The monkeys were kept in a room with a controlled environment (24 °C ± 2 °C, relative humidity of 40–70%, 12 h light/dark cycle) and provided with food (twice per day) and adequate drinking water. At the experimental endpoint on day 21, the macaques were anaesthetized with Sutra (5–10 mg kg−1, intramuscular injection) and subsequently underwent MRI scanning.

Mice behaviour test

For the cylinder test, a mouse was placed inside a glass cylinder with a diameter of 10 cm and a height of 25 cm. The number of times that both paws were placed on the cylinder wall during exploration for 3 min was counted and recorded. For the hind-limb clasping test, each group of mice was suspended by the tail for 14 s, and their abilities of hind-limb clasping were monitored by video recording using an infrared camera (JIERRUIWEITONG, HW200-1080P). The 14 s trial was split into 7 intervals of 2 s each. The mouse was awarded a score of 0 (no clasping) or 1 (clasping). The scores for the 7 intervals were summed for each mouse, allowing a maximum score of 7. The test was video recorded and analysed later in a blind fashion. For the grid walk test, the mice were allowed to walk on a 1-m-long wire grid. With each weight-bearing step, a paw might fall or slip between the wires, which was recorded as an error. The total steps and times were also counted and recorded. All behavioural data were analysed by investigators who were blind to the genotypes and treatments of the mice.

Primary mouse glial cell isolation

For mouse brain cultures, the brains were collected from pregnant C57BL/6J mice at 18 days of gestation. In brief, the brains were removed and incubated for 20 min in an enzyme solution (10 ml DMEM, 2 mg cysteine, 100 mM CaCl2, 50 mM EDTA and 200 U papain) and then rinsed with Ca2+/Mg2+-free Hanks’ balanced salt solution and triturated in 10% DMEM. Cells were diluted to a final concentration of 5 × 106 cells per ml and plated on a poly-l-lysine-coated 48-well plate, which was maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator.

Immunofluorescence imaging

293T cells were seeded in a 12-well plate containing a cover glass at a density of 6 × 104 per well 24 h before the transduction of RIDE and Lenti-CRISPR. To detect lentiviral particles, RIDE and IDLV were attached to 0.1% (w/v) poly-l-lysine (Beyotime Biotechnology)-coated cover glass in a 12-well plate with 1 ml PBS by spinning at 1,200 × g for 99 min. Cells and VLPs were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde. The cover glasses were stored in 70% ethanol for at least 15 min and washed three times with PBS. To detect Cas9, cells were stained with anti-Cas9 mAb (1:800, Cell Signaling Technology, #14697), followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 IgG (1:800, Cell Signaling Technology, #4409). To detect Cas9 and p24 simultaneously, cells or VLPs were stained with anti-Cas9 mAb (1:300, Cell Signaling Technology, #14697), followed by anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 IgG (1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #115-545-062), and anti-p24 mAb (1:200, Sino Biological, #11695-R002), followed by anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 IgG (1:300, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #111-605-045). The nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology). The imaging was performed using a confocal microscope (A1Si, Nikon or TCS SP8, Leica Microsystems).

For brain immunohistochemistry analysis, the brains were collected and incubated successively in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight. In brief, tissue sections were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in an ethanol series. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubating the sections in 0.3% H2O2 in methanol for 30 min. The tissue sections were then incubated with anti-GFP antibody (1:1,000, GeneTex, #GTX113617) at 4 °C overnight, followed by anti-mouse secondary antibodies (1:3,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #7076) for 30 min. The sections were then incubated with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Beyotime) for 10 min and counterstained with haematoxylin. The brain tissue sections used for H&E staining were subjected to Prussian blue staining, which was performed using freshly prepared 5% potassium hexacyanoferrate trihydrate and 5% hydrochloric acid. The sections were rinsed in water after 30 min and counterstained with nuclear fast red, dehydrated and covered.

For brain immunofluorescence detection, 7 days after intracerebral administration, mice were killed. Their brains were collected and incubated successively in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde at 4 °C overnight and in 30% (w/v) sucrose for 48 h. For immunofluorescence labelling, sections (30 μm) were permeabilized with 0.4% Triton X-100 and blocked in a washing buffer containing 2% normal donkey serum. A primary antibody was used for overnight immunostaining. After washing three times with PBS, the sections were incubated with a secondary antibody for 2 h in the dark and then stored in an anti-fluorescence quenching sealing solution (including DAPI, Beyotime Biotechnology). The sections were then incubated with primary mouse anti-huntingtin protein antibody (1:500, Sigma-Aldrich, #MAB2166), rabbit anti-glial fibrillary acidic protein primary antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, #80788) or rabbit anti-ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 primary antibody (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, #1798), followed by application with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 IgG (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4409) or anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 IgG (1:1,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #111-545-003). Incubation with mouse anti-NeuN primary antibody (1:4,000, Sigma-Aldrich, #MAB377) was followed by incubation with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 IgG (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4409). To co-stain NeuN with GFP, mouse anti-NeuN antibody (1:4,000, Sigma-Aldrich, #MAB377) and anti-GFP antibody (1:1,000, GeneTex, #113617) were applied with anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 555 IgG (1:1,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #4409) and anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 647 IgG (1:1,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #111-605-045). Brain slices were then imaged using a confocal microscope (A1Si, Nikon) or fluorescence microscope (Pannoramic DESK, P-MIDI, P250, 3D HISTECH) and processed using Pannoramic Scanner software.

To analyse the apoptosis of mouse fundus cells, 10-μm-thick cryosections of eyes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature and then incubated in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS for 30 min at 37 °C. TUNEL staining was performed using an In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche, #12156792910). The TUNEL signal was visualized using a confocal laser scanning microscope with a 40× oil-immersion objective lens (TCS SP8, Leica Microsystems). Fluorescence images of TUNEL-positive cells were obtained at an excitation wavelength of 555 nm (red). The cell nuclei were stained blue with Hoechst 33258 (1:2,000, Thermo Fisher Scientific, #H3569).

To detect the IDLV-GFP distribution after subretinal injection, cryosections of the eyes were treated as described above. Slices were stained with anti-GFP antibody (1:1,000, GeneTex, #GTX113617) and anti-glutamine synthetase antibody (1:1,000, GeneTex, #GTX630654) followed by anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 IgG (1:2,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #111-545-003) and anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 647 IgG (1:2,000, Jackson ImmunoResearch, #115-605-003).

Single-cell RNA sequencing and analysis

Cellular suspensions at a concentration between 500 and 2,000 cells per µl were sequenced with BD Rhapsody on a NovaSeq sequencing platform at NovelBio. The adapter sequences were filtered out, and the low-quality reads were removed by applying fastp with default parameters62. To identify the cell barcode whitelist, the cell barcode unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) were extracted and the cell expression counts were calculated based on the filtered clean fastq data, followed by the use of UMI tools for single-cell transcriptome analysis63. The UMI-based clean data were mapped to the mouse genome (Ensemble version 100) utilizing STAR mapping with customized parameters from the UMI-tools standard pipeline to obtain the UMI counts for each sample. Cells that contained over 200 expressed genes and a mitochondria UMI rate below 30% passed the cell quality filtering, and their mitochondrial genes were removed from the expression table. The Seurat package (version 3.1.4) was used to adjust the above bias factors to obtain accurate and unbiased single-cell gene expression data. T-distributed stochastic neighbour embedding (tSNE) and principal component analysis (PCA) dimensionality reduction on the calculated principal components were then performed to obtain a two-dimensional representation for data visualization. A PCA plot was constructed based on the scaled data with the top 2,000 highly variable genes, and the top 10 principals were used for tSNE and UMAP constructions. Graphs and K-means clustering were used for cell clustering, and the Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for marker gene analysis. Cell types were determined according to the transcriptional abundance of marker genes. For subtype assessment within the major cell types, we re-analysed cell subsets separately.

Generation of human neurons from iPSCs and RIDE transduction

CHDI-90002166-1 iPSC clonal line (CHDI-66), derived from a male Huntington’s disease patient that carries 43 and 18 CAG repeats, was kindly provided by CHDI Foundation. We generated human neurons from Huntington’s disease patients’ iPSCs that were engineered with a doxycycline-inducible NGN2 expression cassette, as previously described64,65. The NGN2-CHDI-66 line was seeded on Growth Factor Reduced Matrigel (Corning, 354230) (1:100 in Advanced DMEM/F12 (Thermo Fisher, 12634-010)) coated 6-well tissue culture plates in MTesR1 (Stem Cell Technologies, 85850) media and cultured until reaching 90–100% confluency. For NGN2-induced differentiation, MTesR1 media were replaced with induction media supplemented with 2 µg ml−1 doxycycline (Sigma, D989) for 3 days, with daily media change. On the 4th day in vitro (DIV) of differentiation, cells were washed with D-PBS−/− (Thermo Fisher, 14190144) and dissociated into a single-cell suspension with Stempro Accutase (Thermo Fisher, A1110501) and replated at a 125 k cm−2 density in assay plates in maturation media supplemented with a Rock inhibitor (Tocris, 1254) (10 µM). Cells were fed with maturation media supplemented with doxycycline (2 µg ml−1) and DAPT (Tocris, 2634) (10 µM) DIV5–6 and maturation media with DAPT only on DIV7. DIV8–12 cells were fed with half media change with maturation media supplemented with AraC (Sigma, C1768) (1 µM) and switched to maturation media supplemented with laminin (Sigma, L2020-1MG) (1 µg ml−1) from DIV13 onwards for long-term maintenance. For RIDE transduction experiments, the NGN2 CHDI-66 neuroprogenitors were thawed, treated with doxycycline for 2 days to induce differentiation into post-mitotic neurons and cultured for 5 days to allow neuronal maturation. Neuronal cultures were treated with increasing doses of VSV-G-pseudotyped RIDE incorporated with HTT-targeting gRNAs on 7 days post-thaw, and the genomic DNA was collected for on- and off-target analysis on day 18.

On-target and off-target amplicon sequencing for human neurons

DNA for editing analysis was extracted with QuickExtract DNA extraction solution (Lucigen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. On-target editing was analysed using next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based amplicon sequencing as described previously66. In short, amplicons of the on-target loci were generated with Q5 High-Fidelity 2× Mastermix (NEB) using target-specific primers, including adapters for subsequent index incorporation (Supplementary Table 16). After PCR purification using Ampure XP beads (Beckman Coulter), unique Illumina indexes were introduced to the amplicons using KAPA HiFi HotStart Ready Mix (Roche). The PCR products underwent a second round of bead purification before sequencing on an Illumina NextSeq system according to the manufacturer’s protocol. NGS data were demultiplexed with bcl2fastq software. Amplicon sequencing data were analysed using CRISPResso2 software (https://github.com/pinellolab/crispresso2) with the following parameters: –min_paired_end_reads_overlap 8–max_paired_end_reads_overlap 300–ignore_substitutions -q 30 -w 1 -wc -3–plot_window_size 20–exclude_bp_from_left 15–exclude_bp_from_right 15 (ref. 67).

Off-target editing was analysed by multiplexed rhAmpSeq using the rhAmpSeq Library Kit (IDT) with a set of customized rhAmp PCR primer panels designed by the manufacturer68. The rhAmpSeq panel included genomic sites with 4 mismatches and no bulge compared with the target site with the canonical NGG PAM, sites with up to 3 mismatches and no DNA/RNA bulge and sites with up to 2 mismatches and a 1 bp bulge with an NRG PAM. Genomic coordinates for each target region are indicated in Supplementary Data 1. The libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NextSeq system and analysed using the amplicon sequencing analysis pipeline as described above. Data were visualized with GraphPad Prism 10 (GraphPad Software).

Statistics

Data were analysed using GraphPad Prism (7 and 10) and presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean for all experiments (n ≥ 3). Student’s t-tests and analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to determine the P values (95% confidence interval). The description of replicates is provided in the figure legends. The asterisks indicate statistical significance (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; NS, not significant). Statistical analysis of the targeted amplicon deep-sequencing data was performed as previously described69. P values were obtained by fitting a negative binomial regression (MASS package in R statistics) and with the logarithm of the total number of reads as the offset to the control and edit samples for each evaluated site. We adjusted for multiple comparisons using the Benjamini and Hochberg method (function p.adjust in R version 3.6.0). We considered the indel percentage in the gRNA/Cas9-transfected replicates to be significantly greater than the indel percentage in the Cas9-transfected controls if the adjusted P value was less than 0.05, the nuclease-treatment coefficient was greater than zero, and the median indel frequency of the edited replicates was greater than 0.1%. If there was no significant difference between control and CRISPR-treated samples, this variation was not attributed to Cas9 nuclease activity.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses