Cyclopalladation of a covalent organic framework for near-infrared-light-driven photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production

Main

Since the first demonstration in 2005 (ref. 1), covalent organic frameworks (COFs) have emerged as a powerful platform for creating functional porous materials by covalently linking a variety of building blocks. The customizable molecular structures and functionalities of COFs offer promising routes to applications in diverse fields, such as gas storage and separation2,3, sensing4, water harvesting5,6 and drug delivery7,8. In 2014, our group demonstrated9 the use of COFs as light-harvesting materials for photocatalytic solar energy conversion, enabling the storage of solar energy in the form of hydrogen fuel. Covalent organic frameworks have since rapidly evolved as photocatalysts for solar energy conversion and have been successfully employed in various reactions, including CO2 reduction10, organic pollutant degradation11 and the oxidative hydroxylation of arylboronic acids to produce phenols12. However, photocatalytic reactions driven by COFs have so far been restricted to using visible light (<760 nm). There is a burgeoning interest in exploiting near-infrared light (NIR > 760 nm) for photocatalytic applications, particularly as NIR light comprises approximately 53% of the solar spectrum13. One challenge in extending the light responsivity of COF photocatalysts into the NIR region is the relatively low energy of NIR light, which provides limited driving force for photocatalytic reactions. Under these circumstances, it is crucial for NIR COF photocatalysts to possess mitigated charge recombination, enabling efficient use of the absorbed NIR photon energy to drive the chemical conversion reactions. Although some strategies—such as linker protonation14, incorporation of linkers with extended π-conjugation15, or donor–acceptor constructs16—have been developed to extend COF light absorption, only a limited number of strategies have successfully extended the absorption into the NIR region16,17, which further complicates the search for suitable NIR COF photoabsorbers through material screening.

Over the past decade, post-synthetic modification of COFs has been established as an effective approach to enrich the diversity and functionality of COFs. Among the various post-synthetic modification strategies, the metallation of COFs has drawn increasing attention in the field of photocatalysis, as it can introduce active sites for targeted reactions18. In 1965, Cope et al.19 synthesized a cyclopalladated complex derived from azobenzene (Azo), documenting a pronounced red-shift in the optical characteristics. Subsequent investigations further diversified the chemistry of azo-cyclopalladated compounds, resulting in a variety of derived structures20. These cyclopalladated complexes have exhibited remarkable catalytic performance across a range of reactions including C–C cross-coupling, reduction of aromatic nitro compounds and C–H activation21. Nevertheless, despite the recognized utility of cyclopalladated complexes, to the best of our knowledge, their integration into COFs remains unexplored so far.

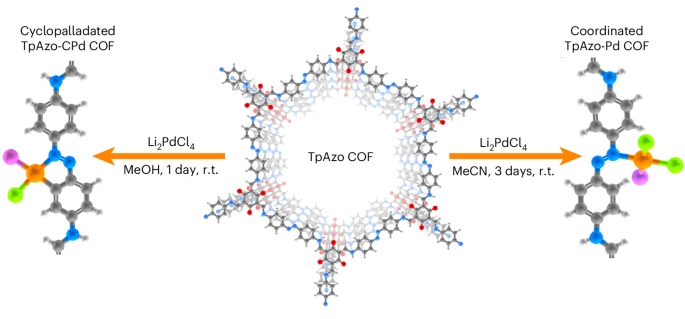

Here we successfully applied cyclopalladation to the TpAzo COF, which is based on 1,3,5-triformylphloroglucinol (Tp) and Azo as the linker, following optimization of reaction conditions. We found that the use of methanol as the reaction solvent yields a highly functionalized cyclopalladated TpAzo COF (Fig. 1). The resulting COF exhibits a uniform distribution of site-isolated palladium atoms without notable formation of palladium nanoparticles, providing an effective solution to circumvent the formation of palladium nanoparticles—a synthetic challenge that is generally encountered in the integration of palladium complexes into COFs22,23,24. Cyclopalladation induces a broadening of the light absorption of the COF, shifting the absorption edge into the NIR region. Taking advantage of this NIR light-harvesting capability, we here introduce a light-harvesting COF photocatalyst for photocatalytic solar energy conversion, affording the production of H2O2—a widely used and valuable industrial chemical.

Left: TpAzo-CPd COF obtained using methanol. Right: TpAzo-Pd COF obtained using acetonitrile. Grey, carbon; white, hydrogen; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; orange, palladium; green, chlorine; and purple, the representation of exchangeable ligands. r.t., room temperature.

Results and discussion

Cyclopalladation of TpAzo COF

In the cyclopalladation of an azobenzene derivative, the formation of the carbon–metal bond involves deprotonation of the phenyl ring, resulting in the generation of HCl as a by-product when using Li2PdCl4. As a number of COFs are sensitive to acidic conditions, β-ketoenamine was adopted as the COF linkage in this work and TpAzo COF was prepared via a solvothermal route. Pyrrolidine was used as the reaction catalyst to enhance the crystallinity of TpAzo (ref. 25). The cyclopalladation was performed using Li2PdCl4 as a palladium source, which was prepared in situ from LiCl and PdCl2. Li2PdCl4 solution was slowly added dropwise to a TpAzo COF dispersion under constant stirring to prevent palladium nanoparticle formation. Two reaction solvents, MeOH and MeCN, were compared for the cyclopalladation reaction. We found that using MeOH results in the formation of site-isolated cyclo-Pd complexes, whereas MeCN only results in coordinated palladium atoms (see below for details). To simplify the discussion, the pristine TpAzo COF is denoted TpAzo, and the post-palladation COF using MeCN or MeOH as solvents are denoted TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo-CPd, respectively.

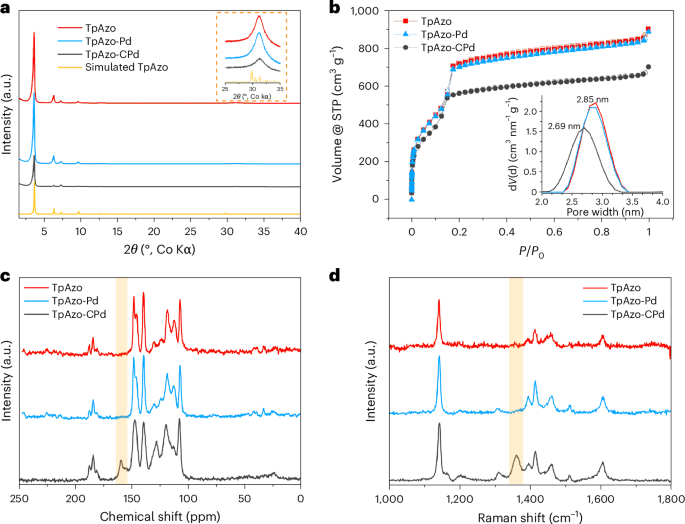

After conducting the post-synthetic palladation on the pristine TpAzo, the amount of anchored palladium was quantified using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES), giving a palladium content of 2.76 ± 0.05 wt% for TpAzo-Pd and 12.60 ± 0.05 wt% for TpAzo-CPd (Supplementary Table 1). TpAzo-CPd exhibits a palladium content four times higher than that of TpAzo-Pd, indicating that the coordination of palladium atoms to TpAzo COF probably varies depending on the solvent used. The crystallinity of the pristine and palladium-functionalized COFs were studied by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis. All three materials—namely, TpAzo, TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo-CPd—exhibit five distinct diffraction peaks (Fig. 2a) at 2θ = 3.6°, 6.3°, 7.3°, 9.6° and 31.1° (Co Kα1 radiation), corresponding to the 100, 110, 200, 210 and 001 reflections, respectively26. This observation suggests that the COF structure is robust enough to retain the crystallinity under the acidic reaction conditions and during the incorporation of palladium ions into the framework. Interestingly, TpAzo-CPd does exhibit noticeable alterations in the relative intensity of the reflections at 6.3° and 7.3° 2θ, which will be discussed in more detail in the following section.

a, Powder X-ray diffraction patterns, including a simulated TpAzo pattern. The inset graph shows a close-up of the region corresponding to the 001 reflection. b, N2 sorption isotherms. Pore size distributions are displayed in the inset graph. STP, standard temperature and pressure. c, 13C solid-state NMR. The shaded area highlights the C–Pd signal in TpAzo-CPd. d, Raman spectra after baseline correction. The shaded area highlights the emerging vibrations in TpAzo-CPd.

Source data

Next, the impact on COF porosity afforded by the incorporation of palladium into the framework was assessed by examining N2 sorption isotherms (Fig. 2b). Both the pristine COF and the palladated COFs exhibit typical isotherms of mesoporous adsorbents, characterized by the distinct inflection in nitrogen uptake at low relative pressure (centred around 0.1 P/P0)27. The N2 sorption isotherm for TpAzo-Pd closely resembles that of pristine TpAzo, whereas TpAzo-CPd exhibits a reduction in gas uptake, which is probably correlated with the substantial incorporation of the cyclo-Pd complex. TpAzo and TpAzo-Pd show very similar Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas of 2,077 m2 g−1 and 2,064 m2 g−1, respectively, whereas the BET surface area of TpAzo-CPd decreases to 1,643 m2 g−1. Furthermore, TpAzo and TpAzo-Pd share the same pore size of 2.85 nm. In comparison, TpAzo-CPd shows a pore size of 2.69 nm—slightly smaller than TpAzo and TpAzo-Pd (Supplementary Figs. 8–10). The above results demonstrate that the limited palladium functionalization in TpAzo-Pd has a minor impact on the porosity of TpAzo COF. By contrast, the decreased pore size and BET surface area of TpAzo-CPd can be rationalized by the substantial incorporation of palladium species into the pore walls of the framework.

Next, solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) and Raman spectroscopy were performed to confirm the success of cyclopalladation in TpAzo-CPd. As shown in Fig. 2c, the 13C-ssNMR spectra of all three samples exhibit distinct signals between 110 ppm and 140 ppm, and the signals at around 180 ppm assigned to the carbonyl carbon in the keto form of the Tp moiety are present all three samples. Although the majority of signals remained unchanged after cyclo-Pd complex incorporation, an additional peak centred at 159 ppm emerged for TpAzo-CPd. This can be attributed to the aromatic carbon directly bonded to palladium, as documented in the reported literature, which establishes the formation of an organometallic bond through cyclopalladation (see Supplementary Fig. 11 for a detailed assignment)28,29. Furthermore, 2D heteronuclear correlation NMR (1H-13C HETCOR-NMR) was performed to investigate the proton–carbon correlation in TpAzo-CPd (Supplementary Fig. 12). The carbon signal at 159 ppm shows no coupling with any proton, which is consistent with the nature of a C–Pd bond. Moreover, Fig. 2c demonstrates that no obvious change in 13C signals is observed between TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo, even after extending the reaction time to ten days, indicating that no cyclopalladation takes place for TpAzo-Pd (Supplementary Fig. 13). Furthermore, 15N-ssNMR was performed on TpAzo COFs containing an 15N-enriched Azo linker (refer to the Supplementary Information for details). As displayed in Supplementary Fig. 12, TpAzo and TpAzo-Pd exhibit identical 15N-ssNMR spectra, implying a largely unchanged chemical environment of nitrogen atoms in TpAzo-Pd. In contrast, TpAzo-CPd shows a noticeable shift in its spectrum, with the signal for the NH linkage shifted from −243 to −239 ppm, and the signal for the azo nitrogen atoms shifted from −20 ppm to −31 ppm for pristine TpAzo COF and TpAzo-CPd, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 15). The success of cyclo-Pd complex formation in TpAzo-CPd was also confirmed by Raman and Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FT–IR). As displayed in Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 16, the appearance of the peak centred at 1,387 cm−1 in the Raman spectrum and distinct changes in the fingerprint region of the FT–IR spectrum around 1,200 cm−1 are observed for TpAzo-CPd, which can be assigned to the vibrational modes pertaining to the bonding between carbon and palladium atoms in the cyclo-Pd complex30.

Putting the aforementioned structural characterization together, it can be inferred that C–Pd bonding is facilitated under conditions employing MeOH as the solvent, whereas the utilization of MeCN does not favour the formation of C–Pd bonding31. We rationalize the solvent effect by considering that MeOH (19.0 kcal mol-1) has a higher donor number than MeCN (14.1 kcal mol−1)32, which may translate into a better proton accepting ability from azobenzene upon cyclopalladation (Supplementary Fig. 23).

Notably, the cyclopalladation of TpAzo COF enhances structural stability, as TpAzo-CPd maintains its crystallinity and integrity even after 24 h of immersion in 1 M KOH and 3 M HCl, superior to the TpAzo and TpAzo-Pd COFs (Supplementary Figs. 23–25).

Optical properties

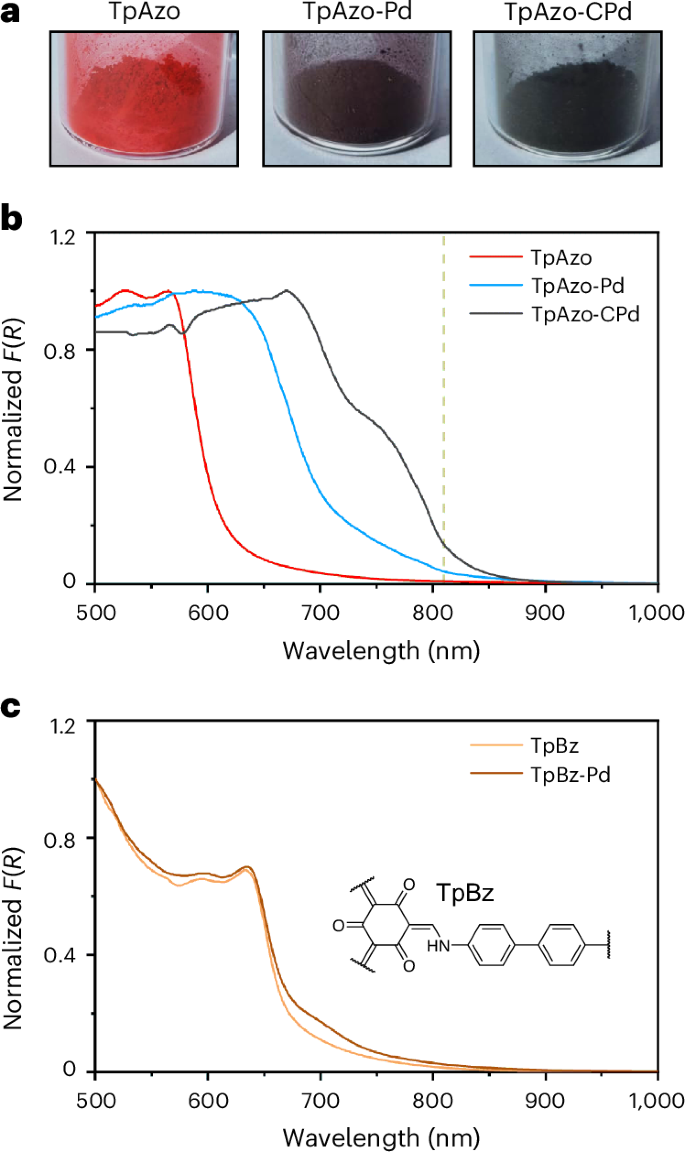

An obvious change in the colour of the COF powder is observed following the incorporation of palladium into TpAzo COF (Fig. 3a). Visible–NIR diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (vis–NIR DRS) was employed to investigate the effect of metal coordination on the optical properties of COFs. The pristine TpAzo COF shows strong visible light absorption with an onset at 599 nm (Supplementary Fig. 27), resulting in a reddish-coloured powder. When palladium was incorporated into the COF, a substantial broadening of the absorption range is obtained: the absorption onset of TpAzo is red-shifted to 692 nm for TpAzo-Pd and 804 nm for TpAzo-CPd (Fig. 3b, and Supplementary Figs. 28 and 29). These results indicate that the cyclopalladation in TpAzo COF enables the extension of light absorption into the NIR region. The influence of palladium on the optical properties of TpAzo COFs probably arises from a metal-to-ligand charge transfer transition, as commonly observed in cyclometallated complexes33,34.

a, Photographs of TpAzo, TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo-CPd COFs powders. b,c, Kubelka–Munk function (F(R)) from vis–NIR diffuse reflectance (R) spectra of TpAzo, TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo-CPd (b; the vertical dashed green line indicates 810 nm), and TpBz and TpBz-Pd (c; the inset represents the chemical structure of TpBz COF).

Source data

A series of control experiments were conducted to confirm whether the observed colour change was a result of palladium complexation. First, it has been demonstrated that the protonation of the COF linkage in acidic media can cause a substantial bathochromic shift in the absorption spectra14. To rule out this possibility, TpAzo COF was exposed to a methanolic solution of HCl at a concentration calculated to match the scenario in which all moles of PdCl2 used in the palladation synthesis released an equivalent amount of protons in the form of HCl. This sample, referred to as TpAzo + HCl, exhibited an absorption spectrum almost identical to that of the pristine COF (Supplementary Fig. 33), thus disproving the notion that the broad light absorption of TpAzo-CPd is due to COF protonation.

Second, 4-dimethylaminoazobenzene, also known as methyl yellow (MY), was employed as a model molecule of TpAzo COF to evaluate the effect of cyclopalladation on optical properties, due to its structural similarity to the TpAzo fragment. Using the same palladation protocol, MY was successfully functionalized to MY-CPd (Supplementary Fig. 34). Notably, the light absorption spectra of these two samples exhibited a similar trend to that of TpAzo and TpAzo-CPd, where cyclopalladation extended the light absorption into the infrared region (with an approximately 100 nm shift in the absorption onset; Supplementary Fig. 35), confirming that the NIR light absorption of TpAzo-CPd originates from cyclo-Pd complexation.

Furthermore, a control COF containing benzidine rather than azobenzene (TpBz COF) was synthesized and used to understand the crucial role of azobenzene on the optical property change after palladium incorporation. As it has been reported that the ketoenamine linkage also coordinates with palladium ions22, using TpBz COF as a control system allows us to verify whether the observed red-shift in absorption is attributable to such coordination. Following the same synthetic protocol used for TpAzo-CPd, palladium was incorporated into TpBz COF (denoted TpBz-Pd). The palladium content of TpBz-Pd was determined to be 3.10 ± 0.03 wt% by ICP-OES, which is similar to that of TpAzo-Pd (2.76 ± 0.08 wt%); however, vis–NIR DRS spectra revealed that only a minor red-shift is obtained for TpBz-Pd compared with pristine TpBz COF, which contrasts the pronounced red-shift in TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo-CPd (Fig. 3c). This comparison suggests that the change in optical properties following palladium decoration is predominantly due to the coordination between palladium atom and azobenzene moiety, rather than the ketoenamine linkage. This result is consistent with the structural characterizations, which identify azobenzene as the primary site of palladium atom coordination.

Palladium environment in TpAzo-CPd COF

Having confirmed the presence of Pd–C bond formation and its optical properties, we next sought to more closely investigate the palladium coordination environment in TpAzo-CPd COF. First, to confirm the presence of chloride atoms in the COF structure, quantification of Cl was performed by elemental analysis (Supplementary Table 2), yielding a weight percentage of chloride of 6.22 wt%. Together with the palladium quantified by ICP-OES, the atomic ratio between palladium and chloride is estimated to be 1.42 (Supplementary Table 2). The atomic ratio of below 2 suggests the possible attachment of exchangeable ligands such as water or methanol to the complex28,31. On this basis, we considered three different coordination scenarios to estimate the ratio of azo groups forming cyclopalladated complexes (Supplementary Fig. 38). The results indicate that approximately 60% of the azo groups in TpAzo-CPd are present as cyclopalladated complexes (Supplementary Fig. 38).

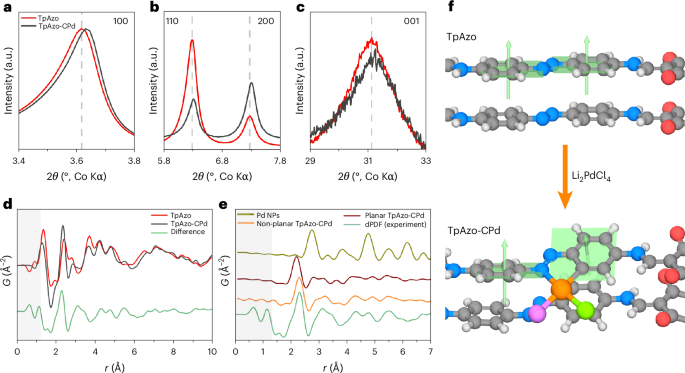

As the cyclopalladated azobenzene crystal structure (azobenzene-CPd) reveals that cyclopalladation can lead to a contraction of the azobenzene moiety (Supplementary Fig. 39), subtle structural modifications can be expected in TpAzo-CPd COF after cyclopalladation. As depicted in Fig. 4a–c and Supplementary Fig. 40, TpAzo-CPd shows a shift in the 100 (2θ of ~0.017°) and 001 reflections (2θ of ~0.128°) compared with TpAzo and TpAzo-Pd. This can be rationalized by the cyclopalladation resulting in a contraction of the Azo linker (Supplementary Fig. 39) as well as a slightly shortened π–π stacking distance due to the distortion of the cyclopalladation complex. In addition, Fig. 4b shows a relative intensity change of the 110 and 200 reflections after cyclopalladation. Such behaviour is due to the additional electron density to the COF pore in the form of –PdCl2 (Supplementary Fig. 41).

a–c, Comparison of 100 (a), 110 and 200 (b) and 001 (c) reflections of TpAzo and TpAzo-CPd PXRD patterns. d, Pair distribution function (G(r)) comparison of TpAzo-CPd and TpAzo, showing a modification in the local structure signal. The shaded grey area represents the low-r region most affected by systematic errors during the data processing. e, Comparison of dPDF signals calculated from different models. NPs, nanoparticles. f, Scheme of proposed models of TpAzo and TpAzo-CPd. Grey, carbon; white, hydrogen; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; orange, palladium; green, chlorine; purple, exchangeable ligands; and light green, representation of the plane described by the phenyl ring and its perpendicular vector.

Source data

Difference pair distribution function (dPDF) analysis was performed to further investigate the palladium coordination environment in TpAzo-CPd35,36,37. As shown in Fig. 4d, substantial peaks can be observed in the dPDF between TpAzo-CPd and TpAzo, particularly at r = 2.3 and 3.1, and between 4–6 Å, suggesting a coherent structure modification due to the presence of bound palladium complexes. Note that no major dPDF signals were obtained when comparing TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo (Supplementary Fig. 42), which further suggests a negligible structural change when using acetonitrile as the reaction solvent. Moreover, the absence of the peaks assigned to the metallic palladium structure (Fig. 4e)—specifically, the Pd–Pd distance at 2.7 Å—allows us to exclude the presence of palladium nanoparticles in TpAzo-CPd. As it has been reported that Pd(II) ions are easily transformed to palladium nanoparticles when synthesizing palladium-functionalized COFs22,23,24, dPDF suggests that our synthesis affords a large amount of Pd(II) complex incorporation without noticeable formation of palladium nanoparticles. Furthermore, the single-crystal structure of cyclopalladated azobenzene compounds reveals a distortion in planarity by the formation of the palladacycle, driven by the steric effect of the coordinated ligands and the adjacent protons31. We therefore also considered the possibility of a planarity change following the introduction of the palladium complex. Introducing a torsion angle of 30° between the two phenyl rings of the azobenzene (Fig. 4e) results in a better match of the nearest-neighbour palladium distance distribution, including Pd–C/N and Pd–Cl bond distances of ~2.0 Å and ~2.3 Å, respectively. Moreover, the non-planar model has a better fit in the 3–6 Å range than the planar one. Combining the above results and other simulations (Supplementary Fig. 43), it is inferred that a distortion of the TpAzo 2D framework is induced by the formation of the cyclopalladation complex (Fig. 4f).

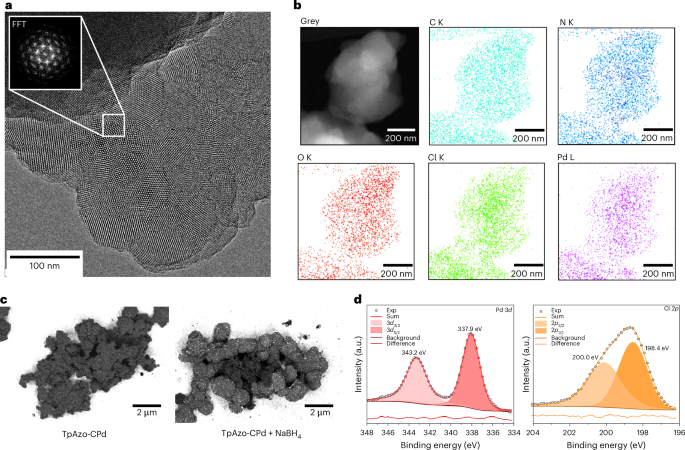

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM), scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) were conducted to study the palladium site isolation and the palladium electronic environment in TpAzo-CPd. As shown in Fig. 5a, TpAzo-CPd displays crystalline domains with a lattice spacing of 2.67 nm (Supplementary Fig. 47). This spacing corresponds to the 100 reflection of TpAzo-CPd, and is well aligned with the distance obtained from the PXRD pattern. Furthermore, a negligible quantity of palladium nanoparticles was found as darker spots under transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Supplementary Fig. 48). Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy coupled with scanning TEM (STEM–EDX) further suggests that palladium and chlorine are uniformly distributed and well-mixed with carbon in TpAzo-CPd, demonstrating homogeneous functionalization by cyclopalladation throughout the sample (Fig. 5b). Scanning electron microscopy images confirm the absence of palladium nanoparticles in TpAzo-CPd across micrometre-sized regions (Fig. 5c). The SEM images collected using an energy-selective backscattered electron detector (ESB) and a type II secondary electron detector (SE2) show no evidence of visible bright dots indicative of palladium nanoparticles. The effectiveness of SEM–ESB and SE2 characterization is validated by measuring a control sample, obtained by treating TpAzo-CPd with NaBH4, thereby reducing the palladium complex to palladium nanoparticles (denoted TpAzo-CPd + NaBH4). The SEM–ESB images of TpAzo-CPd + NaBH4 reveal numerous bright dots signalling the presence of palladium nanoparticles. Further characterizations of TpAzo-CPd + NaBH4 via FT–IR, Kubelka–Munk function analysis and XPS prove that the palladacycle is destroyed upon reduction (Supplementary Figs. 52–54). In the palladium 3d XPS spectrum of TpAzo-CPd, two distinct peaks appear at 337.9 eV and 343.2 eV, which correspond to the 3d5/2 and 3d3/2 core levels of Pd(II) ions forming a chlorinated palladium complex (Fig. 5d)38,39. Furthermore, the peaks at 198.4 eV and 200.0 eV are observed in the Cl 3p XPS spectrum, and are attributed to the 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 core levels of a chloride species (Fig. 5d)40. These results provide compelling evidence that the palladium in TpAzo-CPd mainly exists as isolated Pd(II) sites in the form of cyclopalladation complexes with chloride ions as the ligand.

a, High-resolution TEM image and fast Fourier transform of a selected area. b, STEM–EDX elemental mapping analysis of the area shown at the top left. c, SEM images using ESB/SE2 detectors. d, Palladium 3d and Cl 2p XPS spectra.

Source data

Photocatalytic H2O2 production

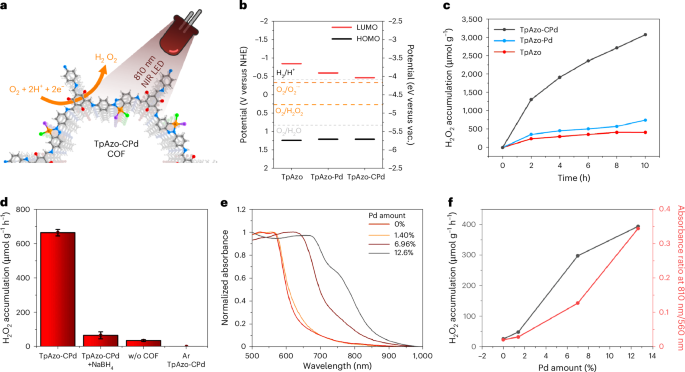

The photocatalytic activity of TpAzo COFs under NIR light (810 nm LED) was evaluated through the generation of H2O2 via the reduction of molecular oxygen in a 2e– process (Fig. 6a). To investigate the thermodynamic ability of these COFs to reduce oxygen, the energy levels of the highest-occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and the lowest-unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) were determined by electrochemical cyclic voltammetry (Supplementary Fig. 56–61). The three COFs show similar HOMO values (approximately 1.2 V versus NHE pH 7); however, different LUMO energy levels were obtained for TpAzo, TpAzo-Pd and TpAzo-CPd, which were located at −0.9 V, −0.6 V and −0.5 V, respectively, versus the NHE at pH 7 (Fig. 6b). We propose that LUMO energy level is altered by palladium coordination to the azo group. This probably perturbs the electronic structure of the N=N bond, which greatly contributes to the LUMO orbital due to its electron-accepting nature41. Nevertheless, the LUMO levels of all COFs thermodynamically satisfy the requirement of photocatalytic oxygen reduction via both a two-step superoxide radical pathway and via a one-step two-electron transfer process (Fig. 6b)42.

a, Schematic representation of H2O2 production under 810 nm LED. Grey, carbon; white, hydrogen; red, oxygen; blue, nitrogen; orange, palladium; green, chlorine; purple, exchangeable ligands. b, Energy levels of the COFs versus vacuum (vac.) and versus normal hydrogen electrode (NHE). Reference water splitting potentials (light grey) are defined at pH 7. c, Photocatalytic production of H2O2 under 810 nm LED irradiation. d, Control experiments on H2O2 production after 2 h of illumination. Error bars were calculated from three independent photocatalytic experiments. Data are presented as mean value ± s.e.m. e, Vis–NIR absorbance spectra from diffuse reflectance spectroscopy of TpAzo-CPd COF with different palladium amounts. f, H2O2 production from a series of TpAzo-CPd COFs with different palladium amount and their relative absorbance at 810 nm.

Source data

The photocatalytic production of H2O2 by TpAzo COFs was measured with an 810 nm LED using a constant oxygen flow of 100 ml min–1, with benzyl alcohol used as the sacrificial electron donor, and the amount of photocatalyst optimized to 4 mg (Supplementary Fig. 64). As shown from the 10 h of continuous tests (Fig. 6c), TpAzo-CPd COF exhibited a higher H2O2 production rate (652.2 µmol g−1 h−1) than TpAzo-Pd COF (178.7 µmol g−1 h−1) and pristine TpAzo COF (119.5 µmol g−1 h−1) (all rates were calculated from the first 2 h of illumination). The cyclopalladated COF exhibited superior activity for H2O2 production under NIR irradiation when compared with different palladium coordination strategies or different COFs with similar palladium loading (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 65). To verify whether H2O2 is produced by photogenerated charges, we measured the H2O2 production rate for 4 h in the dark, which was followed by a period of illumination (Supplementary Fig. 66). Although 2.6 µmol of H2O2 was detected during the first hour for TpAzo-CPd under dark conditions, H2O2 production ceased thereafter. The H2O2 formed in the dark is probably attributable to the incipient self-oxidation of the TpAzo-CPd COF by the purged oxygen, since no H2O2 was detected under argon (Fig. 6d) and obtaining H2O2 via self-oxidation has been reported in other studies on molecular photocatalysts for H2O2 production43. The FT–IR spectrum of TpAzo-CPd after a 10 h continuous illumination test remained identical with the pristine TpAzo-CPd (Supplementary Fig. 68). Apart from some photo-induced palladium reduction (up to 18%) after 10 h irradiation (Supplementary Fig. 69), no chemical structure changes were observed as a consequence of self-oxidation. After illumination, we observed 4 h of continuous H2O2 production at a rate of 551.9 µmol g–1 h–1, which is consistent with the H2O2 production rate in Fig. 6c, thus confirming that photogenerated charges of TpAzo-CPd COF were consumed to produce H2O2. Excluding the small amounts of hydrogen peroxide produced in the dark, the apparent quantum yield of TpAzo-CPd at 810 nm was determined to be 2.2% when using BzOH as the sacrificial agent, and 0.4% when using MeOH (Supplementary Table 3).

Several other control experiments were performed in an attempt to further understand the role of TpAzo-CPd COF for NIR photocatalytic H2O2 production. First, we verified that although palladium nanoparticles can integrate NIR light absorption with catalytic properties, the cyclopalladation complex exhibited superior performance in terms of NIR photocatalytic H2O2 production compared with palladium nanoparticles. As shown in Fig. 6d, only 65.8 µmol g−1 h−1 of H2O2 was obtained with TpAzo-CPd + NaBH4, wherein the cyclopalladation complex was disassembled into palladium nanoparticles, as demonstrated in Fig. 4c. Furthermore, reducing the palladium loading amount in TpAzo-CPd also led to decreased light absorption at 810 nm (Fig. 6e). At a palladium loading of 1.4 wt%, the light absorption at 810 nm was nearly identical to that of TpAzo, and the H2O2 production rate of this sample under 810 nm illumination became negligible (Fig. 6f and Supplementary Fig. 71). These findings underscore the critical role of extended light absorption on photocatalytic H2O2 production as cyclopalladation of the COF proceeds (Fig. 6f).

A series of control experiments and quantum-chemical calculations were performed to better understand the H2O2 production mechanism,. First, several scavengers were used to elucidate the intermediates involved in the photocatalytic reaction (see Supplementary Information for more details); among them, p-benzoquinone (a known O2•–/•OOH radical scavenger) considerably reduced H2O2 generation (Supplementary Fig. 75b). This suggests the critical role of O2•–/•OOH radicals during hydrogen peroxide production, which is typical of the stepwise 1e– pathway in the 2e– oxygen reduction reaction3,44. Furthermore, density functional theory calculations were performed. The resulting energy profiles for the proposed reaction mechanisms agree with the above argument, showing that the stepwise 1e– pathway has lower energies than the direct 2e– pathway (Supplementary Figs. 79 and 82). Moreover, it was observed that participation of the palladium atom in TpAzo-CPd results in lower energies than those involving the hydrogen atom of pore-oriented TpAzo, which corroborates the active role of the palladium centre in the stepwise 1e– oxygen reduction (Supplementary Figs. 78 and 79).

Conclusion

In summary, we have developed a post-synthetic functionalization scheme, incorporating a palladacycle into the azobenzene COF backbone by a quantitative cyclopalladation reaction. The resulting COF, TpAzo-CPd, extends light absorption into the NIR spectrum region and enables the demonstration of a COF NIR photocatalyst. Structural characterizations, including solid-state NMR and Raman spectroscopy, establish that the cyclopalladation complex is obtained using methanol as the reaction solvent, whereas acetonitrile only facilitates non-specific N–Pd coordination without the formation of a C–Pd bond. The cyclopalladated COF (TpAzo-CPd) retains the crystallinity of TpAzo and exhibits a uniform distribution of palladacycles in the frameworks without noticeable formation of palladium nanoparticles. Under 810 nm LED illumination, TpAzo-CPd can produce H2O2 via photocatalytic oxygen reduction. Further investigations confirm that the NIR light absorption induced by cyclopalladation contributes photogenerated charges crucial for photocatalytic H2O2 production. Therefore, this work not only expands the scope of post-synthetic functionalization of COFs by introducing cyclopalladation to the toolbox, but also demonstrates the potential of COFs in NIR photocatalysis. We anticipate that our results will stimulate the rational design of NIR-responsive COFs and advance their applications in harvesting NIR light for solar fuel generation, chemical synthesis, and biomedical applications—particularly in photodynamic therapy for cancer treatment, where NIR light offers considerable advantages.

Methods

Synthesis of COFs

To synthesize TpAzo and TpBz COFs, a pyrrolidine-catalysed procedure was employed to attain highly crystalline TpAzo COF. In a typical COF synthesis, 0.47 mmol of the respective amine (101.3 mg of Azo and 86.2 mg of Bz) and 0.34 mmol of Tp (71.3 mg) were combined within a 6 ml Biotage high-precision glass vial. Subsequently, 4 ml of anhydrous 1,4-dioxane and 80 µl of pyrrolidine (used as a catalyst) were added to the vial. The vial was sealed with a septum cap and subjected to 10 min of sonication to achieve a homogenous dispersion. The reaction was kept at 120 °C on a hot plate without stirring for three days. Upon completion of the reaction period, the vial was allowed to cool naturally to room temperature and then unsealed. The resulting COF powder was filtered and rinsed with THF. To eliminate any residual linkers and catalyst, the COF powder was subjected to 24 h of Soxhlet extraction. Finally, the solvent was exchanged with methanol, and the powder was dried using supercritical CO2.

Palladation of COFs

Consistent reaction conditions were maintained across the solvents to investigate their influence over the palladation process. Initially, Li2PdCl4 was prepared by vigorously stirring 5 mg of PdCl2 and 2.5 mg of LiCl in 10 ml of the respective solvent (MeOH or MeCN) for a duration of 3 h. In a separate 20 ml glass vial, 10 mg of COF was dispersed in 5 ml of the solvent using sonication for 10 min. The COF dispersion was then stirred while the previously prepared palladium solution was added dropwise over approximately 10 min at room temperature. The reaction time was set at 24 h for MeOH and extended to 72 h for MeCN. Upon completion of the reaction time, the resulting powder was filtered and thoroughly washed with a substantial volume of the corresponding solvent (MeOH or MeCN, as appropriate to each case). Finally, the palladated COF powder was air-dried overnight.

To synthesize TpAzo-CPd COFs with different palladium content, the procedure described above was followed but the amount of Li2PdCl4 methanolic solution (0.5 mg of PdCl2 ml–1) was modified accordingly: 10 ml for 12.6 wt%, 7 ml for 9.02 wt%, 5 ml for 6.96 wt%, 2.5 ml for 4.88 wt%, 1 ml for 3.02 wt% and 0.5 ml for 1.40 wt% of Pd.

Synthesis of TpAzo-CPd + NaBH4

To reduce the palladium ions present in the cyclopalladated COF, 20 mg of as synthesized TpAzo-CPd COF was dispersed in 5 ml of MeOH. Then, under continuous stirring, 10 ml of 0.3 M methanolic NaBH4 solution was added dropwise at room temperature. After 24 h of reaction, the COF was filtered and washed with copious amount of methanol. A dark red powder was obtained by air drying the sample overnight.

H2O2 quantification

The quantification of H2O2 was conducted through a spectrophotometric method based on the triiodide procedure. Specifically, 0.5 ml of filtered reaction solution (passed through by a 0.22 µm hydrophilic polytetrafluoroethylene filter) was mixed with 1 ml of 0.1 M aqueous potassium iodide solution and 1 ml of aqueous 0.4 M potassium hydrogen phthalate solution. The resulting mixture was shielded from light for 30 min before UV–visible absorption measurement. To establish a calibration curve, fresh solutions of potassium iodide and potassium hydrogen phthalate were prepared weekly, and the curve points were generated using a commercial 30 wt% H2O2 solution and Milli-Q water.

Photocatalytic H2O2 production

In a typical photocatalytic experiment, 4 mg of COF was sonicated in 9 ml of Milli-Q water for 10 min. Next, 1 ml of sacrificial agent (usually benzyl alcohol) was added to the dispersion. The dispersion was then incorporated into a glass reactor with a quartz top window. The COF dispersion was stirred (200 r.p.m.) and purged with oxygen gas (100 ml min–1) for 10 min before illumination. Finally, the reaction was continuously purged and stirred for 2 h under top illumination using a ThorLabs 810 nm mounted LED (M810L5) at full power. A xenon lamp (Newport, 300 W) equipped with a water filter, a dichroic mirror, and a 420 nm cutoff filter were used for solar simulator experiments. For H2O2 production longer than 2 h (Fig. 6c), stirring and illumination were stopped at specific intervals, and the dispersion was allowed to settle undisturbed for 2 min to separate the aqueous phase (top) from the benzyl alcohol phase (bottom). Next, 0.7 ml of the aqueous phase containing H2O2 was withdrawn using a syringe and polytetrafluoroethylene filter. Subsequently, 0.7 ml of Milli-Q water was added back to the reaction mixture to maintain a constant reaction volume. Before resuming illumination, the reactor was purged with O2 gas for 10 min to restore the oxygen atmosphere. Note that additional methods can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Responses