Deep tissue photoacoustic imaging with light and sound

Introduction

Biomedical imaging has a wide range of applications both in fundamental research as well as clinical diagnosis and treatment monitoring. The scales of biomedical imaging systems can range from imaging single organelles using optical microscopy techniques1 to the entire human body with X-ray computed tomography (CT)2 or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)3. Optical microscopy has the advantage of being able to localize and measure optical parameters (such as absorption/emission spectra) of tissue, which can give highly specific molecular information. However, most optical microscopy systems are only able to image about one millimeter deep into tissue, due to the high optical scattering of tissue. For this reason, there is a gap in the use of optical microscopy in the clinical setting, with the exception of optical coherence tomography for retinal imaging4, where penetration depth is of high importance. The deep imaging methods that are used in clinical medicine generally rely on ionizing radiation (projection radiography, X-ray CT, nuclear imaging), radio-frequency signals (MRI), or acoustic signals (ultrasound).

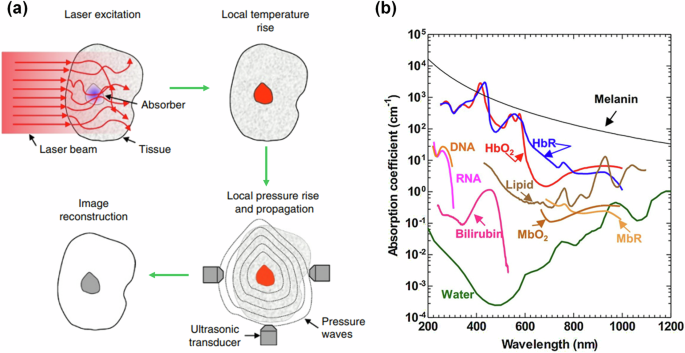

Photoacoustic (PA) imaging (also called optoacoustic imaging) combines both light and sound for deep tissue imaging5,6. The technique harnesses the photoacoustic effect discovered by Alexander Graham Bell in the 19th century7. A short laser pulse (generally nanosecond-scale pulse width) is used to probe the imaging target. Optical absorbers inside the target will absorb the light, where the absorbed optical energy is partially or completely converted into heat. The quick heating of the absorbers leads to thermoelastic expansion, resulting in a pressure wave being emitted from the target (Fig. 1a). Combining optical excitation and acoustic detection, photoacoustic imaging achieves optical contrast with acoustic resolution at depths beyond the optical diffusion limit. Photoacoustic imaging provides structural, functional, and molecular information with multispectral optical excitation (Fig. 1b). Photoacoustic imaging can further be divided into two subcategories: photoacoustic microscopy (PAM) and photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT)8. PAM often uses focused light and/or high-frequency focused ultrasound detection for high-resolution imaging but has a limited imaging depth of less than a few millimeters. By contrast, PACT generally uses diffuse light for excitation and low-frequency ultrasound for detection, allowing for deep tissue imaging (>1 cm depth). As this review is focused on deep tissue applications, only recent advancements in PACT will be discussed. For more information on PAM, the reader is referred to these comprehensive reviews9,10,11.

a Physical process for photoacoustic signal generation and detection. Short-pulse optical illumination excites the target, resulting in optical absorption and, subsequently, nonradiative relaxation. This is followed by thermoelastic expansion, causing an ultrasound wave to propagate away from the absorber to ultrasound detectors (adapted from ref. 8). b Optical absorption spectrum of common biological molecules (adapted from ref. 139). The strong absorption of hemoglobin in the visible and near-infrared bands allows for angiographic imaging by PACT. HbO2 oxygenated hemoglobin, HbR deoxygenated hemoglobin, MbO2 oxygenated myoglobin, MbR reduced myoglobin, DNA deoxyribonucleic acid, RNA ribonucleic acid.

PACT is finding increasing applications in both preclinical research and clinical practice. By bridging the gap between molecular specificity and deep tissue imaging, PACT is uniquely positioned to advance our understanding of complex biological systems and improve clinical outcomes. Its ability to safely provide real-time, deep-tissue insights into the structural, functional, and molecular dynamics of living tissues has made it an invaluable tool in areas such as oncology12 and neurology13. As PACT technology continues to evolve, the integration of PACT into standard clinical practice has the potential to enhance diagnostic precision and solidify itself as a useful tool in the modern biomedical imaging arsenal.

PACT system configurations and methods

Typical PACT system configurations

There are two major design considerations for a PACT system: the method of optical excitation and the method of acoustic detection. PACT needs short-pulsed diffuse optical illumination for signal generation in deep tissues. These stringent requirements lead to short-pulsed lasers (e.g., Q-switched Nd:YAG laser) being the most common optical illumination technique in PACT. For multispectral imaging, multiple excitation wavelengths are required to probe the target. This is generally done using an optical parametric oscillator (OPO) for laser-based systems. Recently, significant efforts have been made in creating light emitting diode (LED) based PACT systems, which come at a much lower cost than the laser-based systems14,15. By combining multiple wavelengths of LEDs, multispectral PACT can be achieved16.

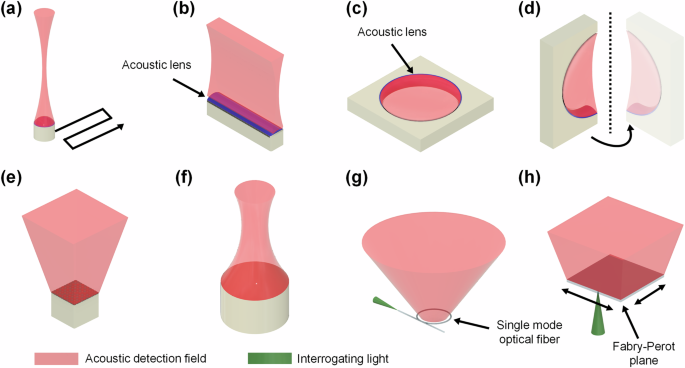

There are many options available for the choice of acoustic detection for a PACT system. A common configuration that is beneficial for a low-cost system is using one (or a few) focused single-element transducer17,18 (Fig. 2a). By scanning the single-element transducer, 2D or 3D PA signals can be acquired. The field-of-view (FOV) and imaging time depend on the scanning parameters. While the single-element-based PACT systems have the benefit of a low cost and simple design, they are susceptible to motion artifacts and require a long scanning time. As an alternative, there is the linear-array transducer (Fig. 2b), which is the most common transducer choice for a PACT system, particularly for clinical applications19. Linear-array-based PACT systems allow for parallel detection of signals along a lateral-axial plane, resulting in 2D imaging with the frame rate mainly limited by the pulse repetition rate of the laser. These transducers generally have aperture widths ranging from ~1.5 cm to several centimeters20,21, which is generally dependent on the central frequency (or element pitch size) and number of elements of the transducer. Commercial linear-array transducers are commonly integrated with an acoustic lens to focus signals along the elevational axis, which is beneficial for 2D imaging. By scanning the transducer and acquiring data along the elevational axis, linear-array transducers can produce volumetric data. However, linear-array volumetric data acquired by scanning suffers from poor resolution and sensitivity along the elevational axis, which is limited by the built-in acoustic lens22. Furthermore, linear-array-based PACT systems suffer from severe limited-view artifacts due to their relatively small detection aperture23. Ring-array-based PACT systems are analogous to linear-array systems but in a circular configuration (Fig. 2c). This geometry mitigates limited-view artifacts and improves penetration depth due to surrounding ultrasonic detection and optical illumination. For this reason, ring-array-based PACT systems have been frequently used in preclinical research applications, particularly for whole-body small-animal imaging24. Like linear-array transducers, ring-array transducers are also frequently designed with acoustic focusing along the elevational axis, which optimizes 2D imaging, but limits the ability to produce quality 3D images with elevational scanning. Ring-array transducers for preclinical PACT are usually ~8 cm in diameter with depth-of-focus regions of about 2–3 cm in diameter24. Variations of ring-array transducers, such as half or partial ring arrays, can be scanned or rotated to generate a large synthetic-detection aperture, such as a spherical or hemispherical aperture25 (Fig. 2d). There are also 2D-array transducers for 3D PACT, such as a planar matrix-array (Fig. 2e) or a hemispherical-array (Fig. 2f). Despite a larger number of elements, planar matrix-array transducers generally have FOVs on the order of a few centimeters26. Hemispherical-array transducers used in PACT have reported FOVs in the lateral plane ranging from 127 to 4 cm2 28, which is often further extended by scanning the transducers. 2D-array transducers have the distinct advantage of volumetric imaging with a single excitation laser pulse. As such, these 2D-array-based PACT systems can achieve high 3D imaging rates, making them useful for time-sensitive biomedical applications such as brain imaging and cardiac imaging.

a PACT with a focused single-element transducer. By sweeping or scanning the single-element transducer, a synthetic 1D or 2D detection aperture can be made for 2D or 3D PACT, respectively. b PACT with a linear-array transducer, which allows for parallel detection of ultrasound along one dimension, providing real-time 2D imaging. c PACT with a full ring-array transducer. By providing surrounding ultrasound detection, limited-view artifacts are reduced. d PACT with a rotating half ring-array transducer, which can achieve a 4(pi)-steradians detection coverage, making it a full-view detection method. e, f PACT with 2D transducer arrays such as the matrix-array (e) or the hemispherical-array (f), which can provide real-time 3D imaging by detecting along a 2D surface in parallel. g, h PACT with optics-based ultrasound detectors such as the micro-ring resonator (MRR) (g) or the Fabry-Perot interferometer (h), which can provide broad detection bandwidths, wide detection angles, and improved SNR compared with traditional piezoelectric-based transducers. Note that all detection configurations here can be translated or rotated to expand the effective detection aperture and field-of-view, at the expense of imaging time.

Optical sensors for ultrasound detection

A growing area of research in PACT techniques is the use of all-optical ultrasonic detectors29. Optics-based ultrasonic detectors have several key advantages over traditional piezoelectric detectors. First, optics-based sensors have a broad detection bandwidth that is more suitable for inherently broadband photoacoustic signals. Second, the sensitivity of optics-based detectors is not necessarily related to the size of the sensor, which can allow for small detectors with large detection angles. Third, optics-based detectors can be made transparent, allowing for coaxial light delivery and ultrasound detection for a PACT system, and thus improved light delivery efficiency. Finally, optics-based detectors are less sensitive to electromagnetic noise compared with piezoelectric detectors.

Two examples of optical acoustic detectors have shown significant progress in recent years: the micro-ring resonator (MRR) (Fig. 2g) and the Fabry-Perot interferometer (Fig. 2h). The MRR gained popularity as an ultrasonic detector for PAM systems30,31,32, due to the need for only a single-element detector in PAM. However, in recent years there has been a transition towards applying MRR detectors for PACT systems. In 2022, Rong et al. showed the feasibility of MRR-based PACT, by phantom, in-vitro, and in vivo studies33. In 2023, Nagli et al. developed their silicon photonics acoustic detector MRR (SPADE-MRR) PACT system, achieving lateral and axial resolutions of ~50 and ~20 µm, respectively34. Soon after, Pan et al. created the first array of MRRs for parallel detection and applied them to PACT. This method retained the high image quality achieved by the MRR sensors (each MRR had a bandwidth of 175 MHz) and improved the volumetric imaging speed by 15 times by using 15 detectors in parallel35.

Fabry-Perot optical sensors have also seen great advancements over the past few years for PACT systems. The concept of applying a Fabry-Perot interferometer as an acoustic detection method for PACT was first explored in the early 2000s36,37 and has seen continuous improvements since. Traditionally, Fabry-Perot-based PACT systems rely on scanning the interrogating laser beam over the planar Fabry-Perot sensor, which can result in long data acquisition times. In 2022, Ma et al. proposed the use of parallel interrogation for a Fabry-Perot sensor by creating a 4 × 16 fiber-optic array, resulting in a volumetric imaging rate of 10 Hz38. Fabry-Perot-based PACT systems have been applied to various studies, including human vascular imaging39, preclinical brain imaging40, and tumor imaging41. In addition to PACT, a Fabry-Perot detector has recently been applied to ultrasound imaging42. Pham et al. showed a significant image quality improvement in Fabry-Perot-based plane-wave ultrasound imaging compared to traditional piezo-based systems. In this Fabry-Perot-based ultrasound imaging system, a plane ultrasound wave was generated via the photoacoustic effect, by exciting a transmitter-coated surface with a laser pulse, and the back-reflected signals were detected by a Fabry-Perot detector.

Several other types of optical ultrasound detectors have also seen advancements and applications in ultrasonic detection in recent years. One example is the π-phase shifted fiber Bragg grating (π-FBG)43. Rosenthal et al. developed an intravascular PA catheter using a π-FBG for ultrasonic detection, achieving a sensitivity that is orders of magnitude greater than a conventional piezoelectric intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) probe44. The use of a π-FBG detector for all-optical IVUS (AO-IVUS) was reported in 202345. Here, the photoacoustic effect was used to generate ultrasound waves, and a π-FBG was used to detect the back-reflected waves, allowing for high sensitivity and large bandwidth while maintaining a small device size. Other types of optics-based ultrasound detection have been applied for PAM, such as polarization-dependent optical reflection46 and surface plasmon resonance47. However, the broad application of these sensors to deep-tissue PACT has yet to be achieved.

Image reconstruction methods

The method of image reconstruction can greatly affect PACT’s image quality and imaging speed. Many innovative image reconstruction algorithms have been developed in recent years48,49; in this section, we will introduce only a few representative methods.

A robust method for complete photoacoustic image reconstruction was well-described in 2005 by Xu et al. as the universal back projection (UBP) algorithm50. The authors illustrated and implemented this method for three full-view detection scenarios: two infinite parallel planes, an infinite cylinder, and a sphere. The half-time UBP-based reconstruction with dual speeds of sound, which is a variation of UBP, has been applied to whole-body ring-array imaging of mice with reduced imaging artifacts compared with traditional UBP51, by taking into consideration the speed-of-sound mismatch between the mouse and the coupling water. However, most photoacoustic imaging systems do not have full-view detection, and thus many alternative approximative reconstruction methods exist. The delay-and-sum (DAS) algorithm, first adopted for traditional ultrasound image reconstructions, is perhaps the most commonly used method of PACT image reconstruction due to its simplicity and robustness48. However, the DAS algorithm does not provide the best image quality in terms of contrast, spatial resolution, SNR, or limited-view artifacts. The delay-multiply-and-sum (DMAS) algorithm, a variant of DAS also established for ultrasound imaging52, has been recently adapted for PACT image reconstructions53,54,55,56. The DMAS algorithm has been shown to produce enhanced contrast and resolution relative to DAS by reducing the sidelobes of the system’s point spread functions (PSFs), particularly at greater depths. Short-lag spatial coherence (SLSC) imaging was similarly first developed in 2011 for ultrasound imaging by Bell et al.57, and then adapted to photoacoustic imaging in the following years58,59,60. Like DMAS, SLSC can reduce the sidelobes of the system PSF, improving the spatial resolution. Furthermore, SLSC was recently shown to reduce skin tone bias in PACT reconstructions, making PACT more applicable to clinical settings61. The time reversal (TR) method is one of the most popular choices for PACT image reconstruction48. Compared with DAS, TR provides a more complete reconstruction, but with a greater computational cost. In TR, a numerical model of the forward photoacoustic wave propagation is reversed in time62. This modeling allows for incorporating transducer geometry, angular sensitivity, detector sparsity, nonlinear wave propagation, and acoustic absorption by the media, which results in improved fidelity63. TR has been employed by the k-Wave MATLAB toolbox64. Model-based or iterative image reconstructions, which can reduce image artifacts and provide a more quantitative reconstruction, have also been greatly explored for photoacoustic imaging65. However, these methods generally come at a higher computational cost than back projection-based reconstructions. In 2020, Ding et al. described a model-based method for 3D PACT reconstruction, which significantly reduces computational complexity by splitting the model matrix into a sparse matrix with one value per voxel-detector pair and a second matrix corresponding to cyclic convolution66. Similarly, Park et al. described a model-based approach in the frequency-domain, applied specifically to transcranial imaging, which achieved near real-time image reconstructions67. More recently, Dehner et al. presented a novel model-based algorithm that incorporates deep learning (DeepMB) for real-time PACT reconstructions68. DeepMB was shown to achieve improved structural and quantitative accuracy in reconstructed images compared to back projection, while maintaining a high reconstruction speed (32 Hz frame rate with 416 ×416 pixels). Innovative work in PACT reconstructions is enabling real-time 3D PACT with improved quantitative accuracy and reduced artifacts.

Combination of PACT with other deep tissue imaging modalities

A major advantage of PACT is its integration with other complementary imaging methods. Because PACT systems generally use the same transducers as US imaging, various US imaging methods are readily available in a PACT system. Furthermore, due to its use of diffuse optical excitation for PA signal generation, PACT can be combined with wide-field optical imaging as well69,70. PACT has even been co-registered with MRI to provide high-resolution structural and molecular information71. This allows PACT to be a part of versatile biomedical research imaging platforms72. Here, we briefly highlight a few multimodal imaging systems that include PACT.

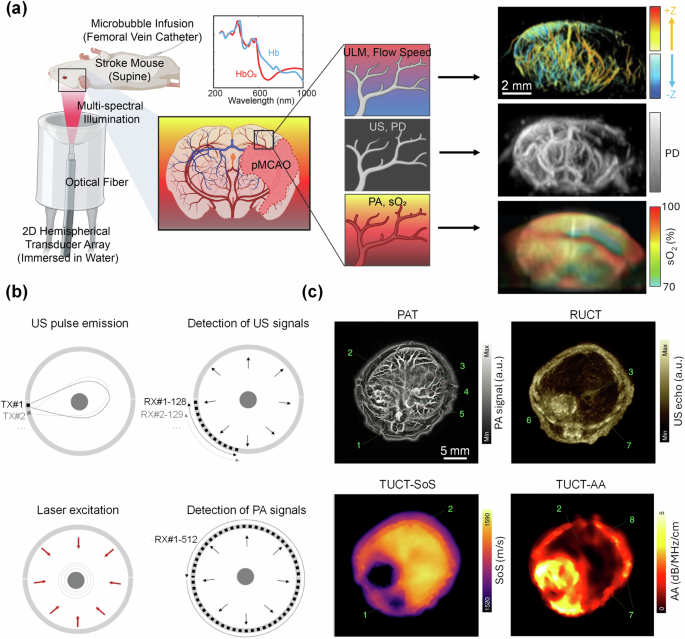

In 2023, Tang et al. described a novel hemispherical-array-based imaging system which combined PACT and ultrasound localization microscopy (ULM)73. ULM is able to break the diffraction-limited resolution of ultrasound imaging by tracking single scatters (e.g., microbubbles) as they flow through blood vessels74. By integrating PACT, power doppler (PD), and ULM in a single, hemispherical-array-based system, high-resolution 3D images of blood vessel morphology, flow velocity, and blood oxygenation can be obtained simultaneously. The hybrid system was applied to the in vivo study of the whole mouse brain with ischemic stroke (Fig. 3a). Similarly, Li et al. integrated an ultrasound-based angiographic imaging modality, acoustic angiography (AA)75, with PACT and high-frequency ultrasound B-mode imaging76. Here, two separate ultrasound transducers (a single-element wobbler and a linear array) were co-registered to provide 3D data from the three imaging modes. This system was applied to in vivo mouse studies of pregnancy and ischemic stroke77,78. Ring-array transducers can be used to map the speed of sound of a medium, through transmission ultrasound computed tomography (TUCT)79,80, similar to fan-beam X-ray CT. In 2019, Mercep et al. integrated a preclinical ring-array-based PACT system81 with reflection US, speed of sound mapping, and acoustic attenuation mapping into a single system (Fig. 3b, c). The integrated system was applied for multiple preclinical studies, including the investigation of mammary tumors82 and fatty liver disease83. The speed of the sound map can additionally be used for correcting the PACT and ultrasound reconstructions84. This can be particularly important in the clinical setting, where acoustic heterogeneities can affect image reconstructions in deeper tissues. In 2021, Pattyn et al. demonstrated, in a phantom study, the improved image reconstructions for a full ring-array-based PACT system by using the speed-of-sound map85. This was also demonstrated in vivo in mice and humans by Zhang et al. in 202286.

a Multimodal PAULM system based on a hemispherical transducer array. PAULM integrates photoacoustic imaging, power doppler (PD) ultrasound, and ultrasound localization microscopy (ULM) for high-resolution structural, functional, and molecular imaging (adapted from ref. 73). b Acquisition modes for ring-array-based TROPUS imaging system. c Representative images of TROPUS in a mouse abdominal region, including PACT, reflection ultrasound computed tomography (RUCT), transmission ultrasound computed tomography (TUCT), speed-of-sound (SoS) mapping, and TUCT acoustic attenuation (AA) mapping. 1: spinal cord; 2: liver; 3: vena porta; 4: vena cava; 5: aorta; 6: stomach; 7: ribs; 8: skin/fat layer; 9: spleen; 10: right kidney; 11: cecum; 12: pancreas; 13: intestines; 14: muscle (adapted from ref. 81).

Preclinical and clinical applications of PACT

While PACT has become a well-established tool for small-animal preclinical studies in recent years, there have been tremendous efforts toward developing clinical PACT tools for human studies. In this section, we will review a select collection of recently developed PACT systems, both preclinical and clinical, as shown in Table 1.

Preclinical applications

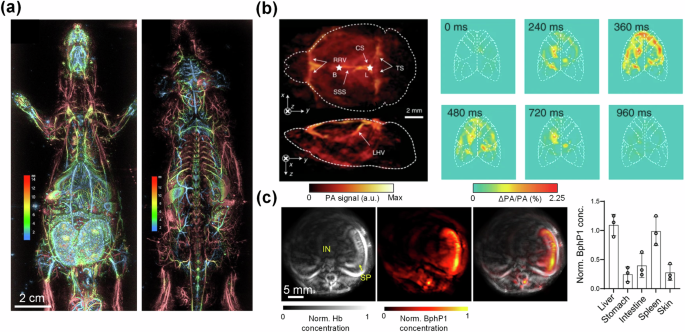

PACT is particularly well-suited for preclinical studies, due to the ability to image through small animals with high contrast and resolution (Fig. 4a)87. One particular area of focus for preclinical PACT has been non-invasive functional and molecular monitoring of the brain13. This is an area of emphasis due to the challenge of understanding the neural dynamics of many debilitating brain diseases, such as stroke88,89, Alzheimer’s90, epilepsy91, and more. In 2019, Gottschalk et al. demonstrated the use of hemispherical-array-based PACT for whole-brain mapping of both hemodynamics and neural activity in conjunction with a genetically encoded calcium indicator, GCaMP6f (Fig. 4b)69. In their study, they found that the PA-measured brain activity via GCaMP6f was stronger than the corresponding fluorescence responses. In 2022, Ni et al. applied the same system to detecting amyloid-β deposits in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease92, and validated the use of PACT for non-invasive monitoring of the progression of Alzheimer’s disease, with high specificity to individual brain regions. This system was further applied to the detection of circulating tumor cells in the brain93, which can provide insight into cancer metastasis.

a Whole-body ventral (left) and dorsal (right) depth-encoded images of a rat using a hemispherical-array-based PACT system (adapted from ref. 140). b PACT image of the brain vasculature (left) and relative increase in PA signals (right) in response to stimulation of GCaMP6f-expressing mice using a hemispherical-array-based PACT system (adapted from ref. 69). c Ring-array-based PACT of a transverse section of a BphP1-expressing mouse, showing total hemoglobin concentration (left), BphP1 concentration (middle), and an overlay (right). Concentrations of BphP1 were measured in the liver, stomach, intestine, spleen, and skin of the mice (adapted from ref. 99).

In addition to brain imaging, preclinical PACT has also been focused on the study of cancer development, metastasis, and treatment. PACT can quantify the blood oxygenation levels inside and surrounding the tumors, using hemoglobin as the endogenous contrast. In 2020, Liapis et al. used the eigenspectra multispectral optoacoustic tomography (eMSOT) system, based on a partial ring-array transducer, to monitor the hemodynamics of a breast cancer model in response to bevacizumab therapy94. The eMSOT system was able to quantify whole-tumor oxygenation, revealing a large negative oxygenation gradient that developed from the boundaries to the center of the untreated tumor. In 2021, Karmacharya et al. similarly used PACT to monitor hemodynamic responses to focused ultrasound therapy in a hepatocellular carcinoma tumor model95. The authors found that following focused ultrasound therapy, there was a reduction in both oxygenation and total hemoglobin concentration inside the tumor. The reduction was proportional to the applied focused ultrasound intensity. In addition to hemodynamics, PACT can be used to monitor the biodistribution of nanoparticles in the deep tissues for photothermal and photodynamic therapy of cancer in the preclinical setting96,97.

Taking advantage of its inherent sensitivity to optical absorption contrast, PACT can image both exogenous contrast agents and genetically encoded reporters, enabling whole-body mapping of molecular activities. One example is the high-sensitivity PACT of photoswitchable phytochromes such as BphP1 and DrBphP specifically expressed in biological tissues, first established by Yao et al. in 201698. The phytochromes have two chemical configurations with corresponding optical absorbing states that can be optically and repeatedly switched by exposing the phytochromes to different wavelengths of light. By imaging the phytochromes in the two absorbing states with PACT, the differential signals from the phytochromes can be extracted, while the strong background signals from the blood can be effectively suppressed. In 2022, using a transgenic mouse model, Kasatkina et al. quantified relative expression levels of BphP1 in multiple major organs in vivo using a ring-array-based PACT system (Fig. 4c)99. In 2023, Ma et al. applied a similar concept to imaging reversibly switchable thermochromics (ReST)100. As opposed to phytochromes, the ReST were switched between the two unique absorbing states by applying heat, and the ReST signals could be extracted by observing the differential signals between the two states. As research progresses, PACT stands to become an indispensable tool for preclinical research, with the promise of improving research through increased efficiency and providing more quantifiable metrics.

Clinical applications

There have been increasing applications for PACT in the clinical setting, with significant advancements in recent years, including vascular imaging, dermatological imaging, adipose tissue imaging, musculoskeletal imaging, and gastrointestinal imaging101. Here, we focus on two specific applications: breast imaging and radiation therapy monitoring, which we believe have shown the most clinical impacts.

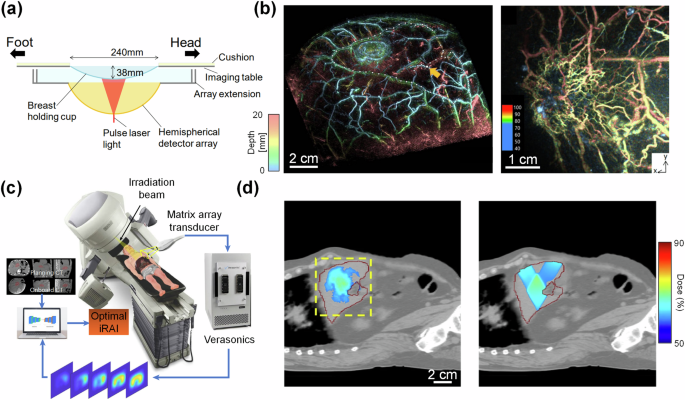

PACT is naturally well-suited for breast imaging due to its unique geometry and the lack of acoustically attenuating structures (such as bone or air), allowing for whole-breast penetration. Most whole-breast PACT systems are based on a hemispherical-array or a partial or full ring-array transducer102. These systems are generally capable of detecting ultrasound waves over a large surface of the breast, mitigating limited-view artifacts. For example, Toi et al. developed a hemispherical-array-based PACT system that can provide detailed vascular structures within the whole human breast (Fig. 5a, b)103,104. Using this system, the authors were able to image the vascular environment surrounding breast tumors and quantify the blood oxygenation. Nevertheless, the use of a large hemispherical-array transducer can result in a high cost. The use of linear-array transducers can greatly reduce the overall cost of the system and function similarly to traditional mammography. Seno Medical recently received FDA approval for a linear-array-based PACT for breast imaging, the Imagio system, showing the clinical translatability of linear-array-based PACT systems105,106. In 2019, Nyayapathi et al. developed a dual-scan mammoscope (DSM), which is based on two scanning linear-array transducers for whole-breast imaging107. The breast is compressed between two plates, allowing for two synthetic-detection planes to be generated by scanning linear-array transducers above and below the breast. In 2021, DSM was used in a study of 38 breast cancer patients, wherein the researchers found that tumor-bearing breasts presented enlarged blood vessels with greater background signal variations compared to healthy breasts108.

a Schematic of multispectral hemispherical-array-based PACT system used for breast imaging (adapted from ref. 103). b 3D PACT image of a healthy patient’s breast vasculature (left, adapted from ref. 103), and of a breast tumor vasculature (right, adapted from ref. 104) (color encodes depth). c Schematic of the iRAI system, which uses pulsed x-ray excitation with a matrix-array transducer for real-time 3D imaging of radiation dose delivery. d Measured radiation dose delivery using iRAI (left) compared to planned dose delivery (right). The iRAI image is overlaid with the X-ray CT image. c, d are adapted from ref. 109.

PACT has recently found a promising application in monitoring radiation dose during radiation therapy procedures. In traditional PACT, visible or NIR light is used to probe the tissues. However, this limits the imaging depth of PACT to only a few centimeters below the skin surface when the light is delivered externally, due to the high optical attenuation in this wavelength band. However, the photoacoustic effect can be produced by using other electromagnetic radiation wavelength bands such as microwave and X-ray. In 2023, Zhang et al. leveraged this principle by developing a PACT system based on the use of pulsed X-ray excitation, which they called ionizing radiation acoustic imaging (iRAI) (Fig. 5c)109. Generally, using X-ray excitation for PACT is undesirable due to the ionizing nature of X-ray photons. However, this is less of a concern for iRAI as ionizing radiation is intentionally delivered to cancer patients during radiation therapy to ablate tumors. By performing iRAI during radiation therapy, 3D images of X-ray absorption (dose delivery) can be reconstructed by detecting the acoustic waves. iRAI was applied and validated in a human study by imaging radiation dose delivery to the liver (Fig. 5d), showing that PACT has the potential to improve radiation therapy procedures with reduced complications.

Discussion and outlook

Wavelength- and target-dependent optical fluence in deep-tissue PACT

There are a few major technological hurdles for PACT in deep-tissue imaging. One such hurdle is the wavelength-, depth-, and target-dependent optical attenuation, making quantitative imaging challenging110. For example, to calculate the blood oxygenation in a deep vessel, multiple excitation wavelengths should be used and their relative optical fluence should be factored into the calculation. However, the optical fluence reaching the vessel is strongly wavelength-dependent. Furthermore, the optical fluence absorbed by the vessel depends on the surrounding absorbers of the tissue. Thus, the true optical fluence at the vessel surface is often unknown and challenging to estimate. A few iterative approaches have been demonstrated in recent years to correct for the inhomogeneity of optical fluence in quantitative PACT111,112. These methods can model the light propagation through the heterogenous medium using the traditional analytical model113, a Monte Carlo method114,115, or deep learning-based approaches116.

In addition to post-imaging approaches, imaging systems can be designed to provide more uniform fluence across multiple wavelengths. One such approach is through the use of internal illumination for PACT117. In 2020, Li et al. developed a graded-scattering fiber diffuser for a more homogenized intravascular excitation inside the pig kidney118. By detecting the PA signals with a linear-array transducer externally on the skin surface, they were able to achieve a penetration depth of ~10 cm. Because light is delivered internally, there was little attenuation before arriving at the target tissue, mitigating fluence heterogeneities across different wavelengths. In 2022, Tang et al. applied internal illumination PACT to image the oxygenation level of blood clots through 10 cm of tissue119, showing the feasibility of functional PACT in deep tissue regions. The concept of imaging with internal illumination can further be applied to the monitoring of laser lithotripsy treatment. Li et al. demonstrated the use of a linear-array transducer to passively detect and reconstruct cavitation induced by intravascular laser excitation, which was shown to help monitor the treatment process120,121.

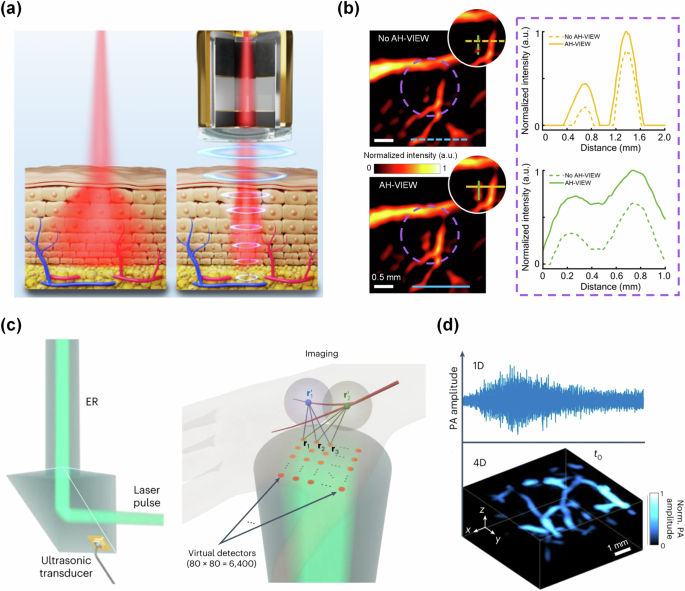

Imaging deeper and faster with PACT

The strong optical attenuation in biological tissue largely prevents PACT from imaging targets beyond a few centimeters. As discussed in previous sections, using X-ray excitation or internal illumination can greatly increase the penetration depth of PACT, but these methods are not generally appropriate for most applications using PACT. By contrast, Lin et al. developed an acoustic hologram-induced virtual in vivo enhanced waveguide (AH-VIEW)122. This method uses focused ultrasound that is applied concurrently with laser excitation to increase the penetration of light into tissue (Fig. 6a). The focused ultrasound alters the refractive index of the tissue inside the high-pressure region compared to the outside, which effectively creates an optical waveguide that better confines the scattered light within the acoustic focal zone. The authors were able to show improved imaging depth in vivo with AH-VIEW-enhanced PA imaging (Fig. 6b).

a Principle of AH-VIEW, wherein focused ultrasound applied concurrently with light excitation provides a waveguide for light through the tissue. b PA images of mouse brain vasculature without AH-VIEW (top) and with AH-VIEW (bottom). The signal profile shows the increased signal strength with AH-VIEW in deep tissues. a, b are adapted from ref. 122. c Schematic showing the ER uses a single ultrasound transducer to encode 6400 virtual transducers in a matrix-array configuration. d Example 1D signal of human vasculature transformed to 4D data via the unique echo signals from each virtual detector in the ER. c, d are adapted from ref. 138.

In addition to imaging deeper, a higher imaging speed with a large FOV is critical for the clinical translation of PACT, especially for capturing dynamic processes. Generally, in PACT, the imaging speed is jointly limited by the laser pulse repetition rate, the number of acoustic channels, and the reconstruction algorithm. Reducing the number of acoustic channels can result in reduced imaging acquisition times, however, doing so may also introduce sparse-sampling artifacts. Sparse-sampling methods123 or using low-frequency ultrasound124 may mitigate sparse-sampling artifacts, allowing for improved imaging speeds while maintaining a large FOV. In a different approach for high-speed PA imaging, a method first developed by Li et al. in 2020 describes the use of a single ultrasound detector in conjunction with an ergodic relay (ER)125,126. In 2023, Zhang et al. applied this method to develop PACT through an ER (PACTER), which is able to encode 6400 virtual ultrasound transducer elements with their unique acoustic signatures (Fig. 6c)127. This system has achieved a volumetric frame rate of 1 kHz. Zhang et al. applied this method to image human skin vasculature (Fig. 6d).

Addressing the limited-view problem in deep-tissue PACT

The limited-view problem in PACT becomes exacerbated in deeper regions due to the reduced receiving-aperture by the transducer. As such, many methods to minimize or mitigate limited-view artifacts have been demonstrated in recent years. The most straightforward method to reduce the limited-view problem is to create a full-view detection aperture. However, this method is not always practical or applicable in the clinical setting, due to large target sizes and the need for fast imaging. In recent years, highly-absorbing exogenous contrast-based methods have been used to address the limited-view problem. In 2018, Dean-Ben et al. developed localization optoacoustic tomography (LOT)128, which is similar to ULM. In this method, optically absorbing microparticles are tracked in the vasculature as point-sources. LOT not only bypasses the limited-view problem, but also is able to achieve super-resolution PACT129. In a similar method developed by Tang et al., microbubbles are used as virtual point sources in PACT130. The microbubbles are not optically absorbing, and thus only act as isotropic deflectors of acoustic signals generated by hemoglobin, which allows for functional and molecular information to be preserved. This method is particularly applicable to the clinical setting because microbubbles are already an FDA-approved contrast agent for ultrasound imaging. In addition to contrast-based methods to mitigate the limited-view problem, there are reconstruction and deep learning-based approaches131,132,133. In 2020, Vu et al. demonstrated the use of a generative adversarial network (GAN) to reduce limited-view artifacts in vivo for linear-array-based PACT134. Such a model is clinically applicable because it does not require any system modification or exogenous contrast.

Overall, PACT has emerged as a transformative imaging modality, bridging the gap between molecular specificity and deep-tissue imaging. Its ability to provide high-resolution images of the optical absorption deep within scattering media has revolutionized our approach to understanding complex biological systems. The recent advancements in PACT technology, coupled with its increasing translation into clinical practice, underscore its potential to enhance diagnostic precision and therapeutic monitoring. As we continue to push the boundaries of PACT, it holds the promise of not only enriching preclinical research but also profoundly impacting patient outcomes.

Responses