Demand-side policies can significantly reduce emissions from energy use in buildings and transport

The policy problem

The Paris Agreement sets a goal to keep global warming well below 2 °C. However, model projections show that this goal is unlikely to be met with current climate policies and actions, indicating a need for additional strategies to further reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Alongside technological supply-side solutions to transition away from fossil fuels, for example with the adoption of renewable energy sources in electricity generation, demand-side strategies involving energy users in sectors like buildings and transport can contribute significantly to emission reductions. Direct emissions from energy use in buildings and transport account for over 20% of global GHG emissions. In buildings, measures such as electrifying energy use through heat pumps, improving insulation, and reducing energy demand through behavioural shifts can significantly lower emissions. Similarly, in transport, electrifying vehicles, enhancing efficiency, and promoting mode shifts to public transit or active modes like cycling can drastically reduce emissions. Determining the most cost-optimal and effective policy mix is a complex systems problem.

The findings

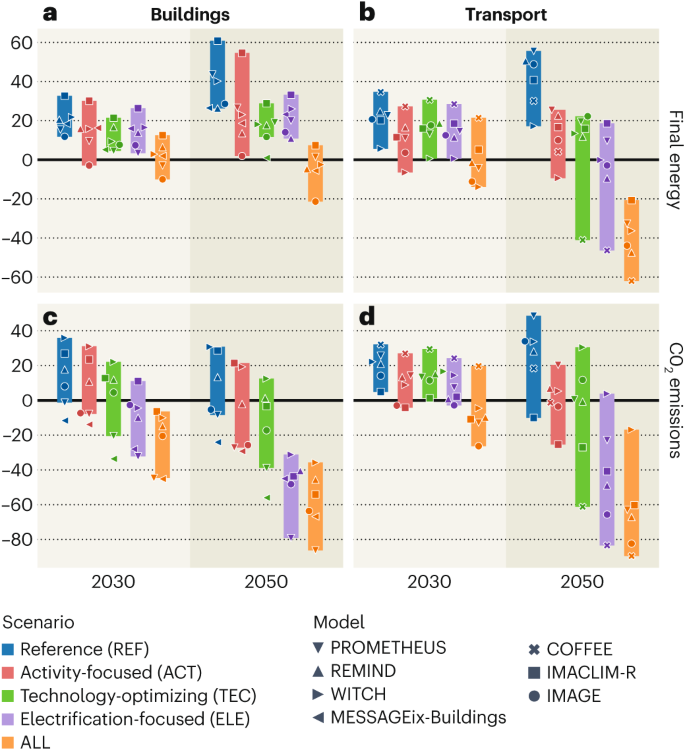

Our analysis shows that a comprehensive set of measures involving end users can reduce sectoral CO2 emissions by 51–85% in buildings and 37–91% in transport by 2050, compared to a scenario based on current policies (Fig. 1). Electrifying energy end-use and switching to alternative fuels delivers the largest emission reductions, though also leads to increases in electricity demand. Reducing or changing energy-using activities including travel distances and mode choices can reduce energy demand and ease pressure on the electricity supply. So too can using more efficient technologies. The combination of all measures leads to significant further emission reductions, despite some offsetting interactions such as the reduced emission-reduction potentials of heat pumps when homes are better insulated. It is important to note, however, that the successful implementation of these policies depends on multiple conditions, such as broader societal support, which was not explicitly considered in this study.

a–b, Final energy use in buildings (a) and transport (b). c–d, CO2 emissions from buildings (c) and transport (d). The figure shows model results for five scenarios: a business-as-usual reference (REF), reducing or changing energy-using activities (ACT), adopting more efficient technologies (TEC), switching to electrification or alternative energy carriers as substitutes to fossil fuels (ELE), and a combined scenario (ALL) integrating ACT, TEC, and ELE. All scenarios have current policies implemented. Markers indicate individual model results and bars depict the model ranges. Figure adapted from R. van Heerden et al. Nat. Energy https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-025-01703-1 (2025); Springer Nature Ltd.

The study

Our study uses quantitative scenarios generated with global integrated assessment models (IAMs) that are specifically designed to capture the interactions within and between the energy system, the economy, and the environment. We developed three scenarios that each capture the impact of a specific strategy targeting energy use. In the first scenario end users reduce or change energy-using activities, in the second they adopt more efficient technologies, and in the third they switch to electrification or alternative energy carriers as substitutes to fossil fuels. Using a structured questionnaire, we also gathered inputs from policymakers and experts in demand sectors to refine the scenarios. We quantitatively interpreted and quantified the scenarios through 2050 using seven IAMs. Finally, we compared the resulting emission reductions per strategy across the set of models and scenarios and analysed the results to better understand the main factors driving these reductions.

Responses