Dendritic phytic acid as a proton-conducting crosslinker for improved thermal stability and proton conductivity

Introduction

In recent years, much effort has been focused on developing proton exchange membranes (PEMs) that can operate under high-temperature conditions (>100 °C) and in anhydrous conditions for the development of high-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cells (HT-PEMFCs)1,2. While water molecules facilitate the molecular diffusion of protic species via H3O+ in conventional PEMs3, operating under high-temperature and anhydrous conditions is significantly more challenging due to the lack of an intermediate proton-conducting pathway. To address this issue approaches such as introducing highly proton-dissociative acids4 and improving hydrophilicity5,6 have been considered for achieving highly proton-conductive materials in these conditions.

Phytic acid (PhA) is a non-toxic naturally occurring substance produced during the ripening of seeds. It contains six phosphate groups and is also called myo-inositol hexaphosphoric acid7,8,9. The structure contains high density of phosphoric acid groups with twelve exchangeable protons. This high density of high-dissociative protons is particularly advantageous for enhanced proton-conducting properties for application in fuel cells and redox flow batteries. Thus far, PhA has been exploited to enhance proton conductivity by doping it into various materials, including poly(benzimidazole) (PBI)10, polyanilines11, sulfonated poly(ether ketone) (SPEEK)12, covalent organic frameworks (COFs)13,14, and metal-organic frameworks15. However, the proton conductivity in such systems remains low at elevated temperatures without external humidification. To overcome this limitation, we propose functionalizing phytic acid itself. Recently, we have reported that the proton conductivity of ionic materials such as salt is correlated with the shortening of the protonated interatomic distance (PAD) induced by the acid-base reaction between a highly electroacceptive acid and a highly electron-donating base, resulting in high proton conductivity16,17. For example, acid-base ionic compounds exhibit short PADs when strong electron-donating groups, such as the dimethylamino group are substituted on the base, resulting in higher proton conductivity. Based on this insight, we designed phytic acid functionalized with pyridine bases to obtain ionic phytates. By substituting the para-position in pyridine derivatives with a proton (-H), a methoxy group (-OMe), and a dimethylamine group (-NMe2), we obtain pyridine (Py), 4-methoxypyridine (MeOPy), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), respectively. These substitutions enhance the electron-donating ability of the groups in the order of -H < -OMe < -NMe2. Accordingly, the higher proton conductivity can be envisaged for phytates with substituents in the order -H < -OMe < -NMe2. Thus, we hypothesize that the proton conductivity of phytates will follow the same order.

Herein, we report the synthesis, characterization, and electrochemical properties of dendritic-like phytate proton conductors with high proton conductivity at high temperatures (140 °C) under anhydrous conditions. We further investigate the effect of ionic phytates as proton-conducting dopants for PEMs by utilizing sulfonated cellulose (Cell-SA) as the base polymeric proton conductor18,19. This report describes that the performance of sulfonated composites can be enhanced via acid-base interactions between a sulfonated polymer and a composite formed by such interactions. Furthermore, the salt-porous sulfonate composites resulted in improved thermal, structural stability, and proton conductivity.

Results and discussion

Initially, prior to the preparation of three different types of ionic phytates, such as Py-PhA, MeOPy-PhA, and DMAP-PhA (Scheme 1), the basic and acidic property were determined by the “pKa rule”20,21,22,23. Phytic acid has 12 exchangeable protons, six of which are strongly acidic (pKa (approx) 1.5), three weakly acidic (pKa = 5.7–7.6), and the remaining three are very weakly acidic (pKa > 10). In contrast, the pKa values of pyridine derivatives such as Py, MeOPy, and DMAP are 5.23, 6.58, and 9.60, respectively. This rule suggests that the difference in the basicity and acidity of the starting components (ΔpKa = pKa (base) – pKa (acid)) likely affects the formation of co-crystals or salts when the ΔpKa values are below 0 or above 2, respectively. As shown in Table S2, the ΔpKa of the six strong acids in PhA ranges between 3.73 and 8.10, including the predictable formation of six salts between PhA and pyridine derivatives in the corresponding phytates. In contrast, for Py-PhA, the pKa difference falls within the co-crystal region for the three weakly acidic protons (−2.37 <ΔpKa < −0.47), while the pKa difference for MeOPy-PhA allows for the formation of both salts and co-crystals in the ΔpKa range from −1.02 to 0.8821. On the other hand, the high basicity of DMAP enables salt formation for ΔpKa above 2. For the very weakly acidic protons (ΔpKa < −0.4), all of them can form co-crystals. Based on these results, DMAP-PhA is expected to allow the construction of nine phytates.

Synthetic protocol of Phytates with pyridine, 4-methoxypyridine, and 4-di(methylamino)pyridine salts.

To explore the potential for salt formation using pyridine derivatives with PhA, the synthesis of dendritic-like phytates was carried out via acid-base reactions between PhA and pyridines, including Py and MeOPy (6 equivalents per PhA) and DMAP (6, or 9 equivalents per PhA) under aqueous conditions at room temperature. The resulting phytates were obtained as fine white powders, including 6Py-PhA, 6MeOPy-PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA in quantitative yields. The 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra confirmed the proposed chemical structures (for NMR spectra see Supplementary Fig. 1–12). The Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectra for all phytates including 6Py-PhA, 6MeOPy-PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA (for FTIR spectra see Supplementary Fig. 13), demonstrated the presence of PhA and the three pyridine derivatives (Py, MeOPy, and DMAP) without any structural destruction during the acid-base reactions. Figure 1a, b shows characteristic bands attributed to C=N and C=C bonds of the pyridine ring at 1445 and 1460 cm−1, which shifted to a higher wavenumber after PhA modification24, indicating protonation of the pyridinium ring by PhA. A new, strong peak at 1560 cm−1 supports the appearance of a newly formed N−O bond between PhA and the pyridinium ring25. Additionally, comparisons between Py-PhA, MeOPy-PhA, and DMAP-PhA revealed gradual shifts in the characteristic peak of PhA at 1640 cm−1 (-OH) toward higher wavenumbers, increasing with the electron-donating strength of the substituents (-H < -OMe < -NMe2) (Supplementary Fig. 13). This shift reflects the protonation of the pyridine ring by the acidic protons (-OH) of PhA26. These findings confirm that the acid-base reactions successfully formed salt structures. The thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) curves (for TGA curves see Supplementary Fig. 14) revealed that DMAP-PhAs exhibit high thermal stability, decomposing only above 250 °C, while Py-PhA and MeO-PhA decompose around 100 °C. This indicates that only DMAP-based ionic phytates possess sufficient temperature tolerance for HT-PEMFC applications operating above 100 °C. The increased thermal stability of the DMAP-based ionic phytates compared to Py-PhA and MeOPy-PhA can be attributed to two main factors: the higher boiling point of DMAP compared to MeOPy, and the stronger acid-base interaction between DMAP and PhA due to DMAP’s higher basicity.

a FT-IR spectra of 4-dimethylaminopyridine and Phytic acid 4-dimethylaminopyridine salts with different molar ratios (PhA:DMAP = 1:6 or 1:9) and (b) trimmed image between 2000 and 400 cm−1. c Computational simulation model for (I) 6DMAP-PhA and (II) 9DMAP-PhA. d Calculated energy of PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA. e Protonic acid terminal on (I) PhA, (II) 6DMAP-PhA, and (III) 9DMAP-PhA. f The temperature-dependent proton conductivity of DMAP-PhA salts with different molar ratios (PhA:DMAP = 1:6 or 1:9).

Computational analysis

Computational simulations were performed on PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA, based on the molecular model depicted in Supplementary Fig. 15a, b and Fig. 1c, to elucidate the effect of base modification on proton conduction. As represented in Fig. 1d, the calculated formation energy of 9DMAP-PhA was lower than that of 6DMAP-PhA, indicating superior stability of 9DMAP-PhA. The reduced energy value correlates with the higher thermal stability of 9DMAP-PhA. The primary proton-conducting site in DMAP-PhA is the six protonic acid sites on PhA (Supplementary Fig. 15b). Analysis of the oxygen-hydrogen interatomic distance in the protonic acid group, based on the computational model, predicts the proton dissociation property, a parameter directly correlated with proton conductivity27. Table S4 summarizes the oxygen-hydrogen interatomic distances at each terminal of the six phosphoric acid moieties for PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA. Figure 1e (I–III) illustrates one phosphoric acid moiety (PA1) for each compound: PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA. In 6DMAP-PhA, DMAP is attached to one terminal (O1–H1), whereas in 9DMAP-PhA, two terminals are modified (O1–H1 and O2–H2). The interatomic distances were elongated for 6DMAP-PhA (O1–H1) compared to PhA, likely due to the interaction with DMAP. Interestingly, O2–H2 distance in 6DMAP-PhA also increased despite the absence of direct base modification at this site. In 9DMAP-PhA, the distances for both modified terminals were significantly greater than those in 6DMAP-PhA. This trend was observed for all six phosphoric acid groups in 9DMAP-PhA attributed to the higher degree of DMAP coordination. Based on these results, DMAP modification improves the proton conductivity of PhA, and a greater number of DMAP modifications further enhances proton conduction due to the increased degree of proton dissociation in multiple proton terminals.

Thermal, morphological, and proton conductivity studies

The temperature-dependent proton conductivity of pelletized phytates was investigated to elucidate the effect of dendritic salt formation with a strong donor over a temperature range of 60–140 °C (Fig. 1f). The powdered composites were pelletized using Teflon-coated carbon paper, then placed in the measurement cell and connected to an electrochemical potentiostat equipped with a frequency response analyzer for measurement. The proton conductivity plot shows that 9DMAP-PhA exhibits a higher proton conductivity of 2 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 140 °C, within the operating temperature range for high-temperature proton exchange membrane fuel cells (PEMFCs). The slope of the plot, which reflects the activation energy, shifts between 100 and 120 °C for both 9DMAP-PhA and 6DMAP-PhA. This behavior is attributed to the high water affinity of the PhA, which retains moisture below 100 °C, while water desorption occurs above this temperature. This assertion is supported by the observation of water evaporation-related weight loss up to 100 °C, as revealed by TGA analysis. The results indicate that the increased formation of protonated pyridinium in 9DMAP-PhA enhances its proton conductivity, thermal stability, and structural hydrophilicity compared to 6DMAP-PhA. Notably, the enhanced hydrophilicity of DMAP-PhA is advantageous for non-humidified operation, where water molecules are absent as intermediate proton carriers28.

Given the demand for high-temperature and anhydrous operating conditions in PEMFCs, we have further investigated the application of DMAP-PhA as a proton-conducting dopant in sulfonated polymeric PEMs. Various acid-modified polymers have been explored as PEMs, such as SPEEK29, Nafion30, poly(4-styrene sulfonic acid)31, and cellulose sulfonic acid (Cell-SA)32. Among them, we chose Cell-SA with three sulfonic acid groups per repeating unit33, because cellulose, derived from biomass, is widely used in various applications, especially in the paper and board industry. Moreover, Cell-SA exhibits high chemical and oxidative stability34, making it favorable for PEM applications. To synthesize composites, the previously prepared 9DMAP-PhA was combined with Cell-SA using a simple aqueous process in H2O at room temperature. The mixture was stirred overnight to yield white powdered composites, named Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA (x = 10, 25, 50, 75, 300; molecular ratios of 9DMAP-PhA to Cell-SA), in quantitative yields.

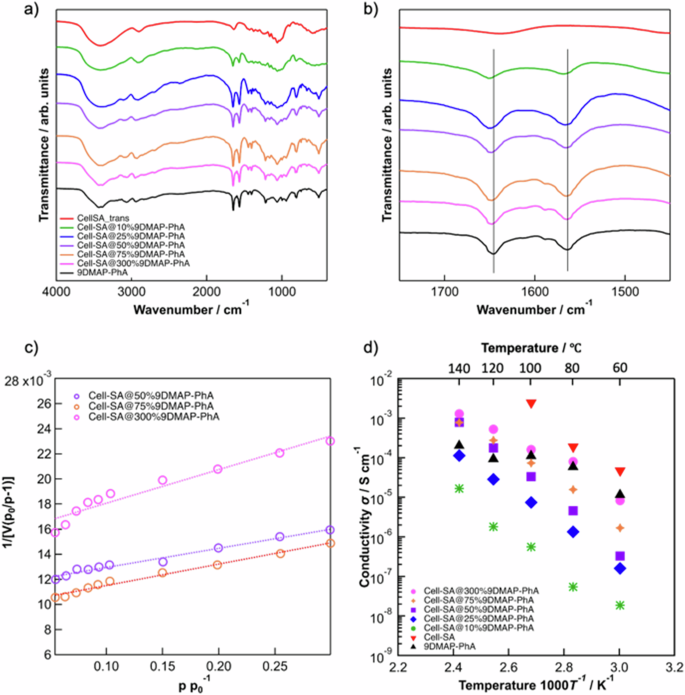

The inherent poor thermal stability of Cell-SA prompts to significant drawback, as its cellulose backbone readily decomposes. However, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 16, the composite material Cell-SA@DMAP-PhA exhibited sufficient thermal stability up to 200 °C, while Cell-SA alone began to degrade at around 120 °C. This improvement suggests its potential of DMAP-PhA as a heat-resistance enhancer in dendritic proton conductors. Typically, thermal resistance in composites improves when strong or weak chemical interactions occur between different domains within the composite. Therefore, we hypothesized that DMAP-PhA enhances the thermal stability of Cell-SA via ionic interactions between the DMAP dendritic chain of DMAP-PhA and the sulfonic acid groups of Cell-SA. A study by A. M. Genaev et al. suggests that the dimethylamino group of DMAP may serve as a protonation site in addition to the pyridinium nitrogen35, supporting the possibility of ionic interactions between the dimethylamino group of DMAP and the sulfonic acid site of Cell-SA. To provide evidence for this interaction, FT-IR analysis of the composites was performed (Fig. 2a). As shown in Fig. 2b, the formation of composites occurs without any chemical decomposition. Notably, the two characteristic bands of DMAP observed between 1700 and 1500 cm−1 shifted to higher wavenumbers with increasing Cell-SA content, indicating possible protonation of DMAP26. Furthermore, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted to elucidate the interaction between Cell-SA and 9DMAP-PhA. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 17a, b, the N1s peak of Cell-SA@300%9DMAP-PhA exhibited a notable shift compared to Cell-SA@75%9DMAP-PhA. These shifts correspond to the enhanced protonation of DMAP by the sulfonic acid cation in Cell-SA, strongly suggesting a salt interaction between the dimethylamino functional group and Cell-SA. Based on molecular simulations using the fragment model of Cell-SA@9DMAP-PhA (for fragment computational model see Supplementary Fig. 18), the binding energy between the dimethylamino group of DMAP and the sulfonic acid group of Cell-SA was calculated to be 10.75 kcal mol−1, confirming the acid-base ionic interaction36.

a FT-IR analysis of 9DMAP-PhA, Cell-SA, and Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA composite with varying composition ratio (x = 10, 25, 50, 75, 300 mol%) and (b) its trimmed image between 1450 and 1750 cm−1. BET surface area plot for Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA with varying composition ratios (x = 50, 75, and 300). The dependence of temperature on the proton conductivity of 9DMAP-PhA, Cell-SA, and Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA composite with varying composition ratios (x = 10, 25, 50, 75, 300 mol%). c BET surface area plot for Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA with varying composition ratios (x = 50, 75 and 300). d The dependence of temperature on the proton conductivity of 9DMAP-PhA, Cell-SA and Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA composite with varying composition ratio (x = 10, 25, 50, 75, 300 mol%).

The morphological properties of Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA composites were investigated using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (for SEM images see Supplementary Fig. 19a–h) and powder X-Ray diffraction analysis (PXRD) (for XRD spectra see Supplementary Fig. 20), with detailed characterization provided in the supporting information. SEM and PXRD results indicate that the morphologies of the composites vary depending on the 9DMAP-PhA content (x = 75–300). At lower 9DMAP-PhA content, partial coverage of DMAP-PhA on Cell-SA was observed, while complete coverage was evident at higher 9DMAP-PhA content. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) measurements were performed to investigate the crosslinking state within Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA. The porosity of the synthesized composites was confirmed through nitrogen sorption measurements at 87.15 K, yielding BET surface areas of 163 m2 g−1 (x = 50), 162 m2 g−1 (x = 75) and 103 m2 g−1 (x = 300) (Fig. 2c). The pore size distribution of Cell-SA@50%9DMAP-PhA, Cell-SA@75%9DMAP-PhA, and Cell-SA@300%9DMAP-PhA (for pore size distribution see Supplementary Fig. 21) demonstrated a single pore system with an approximate pore size of 4–5 nm, indicating the presence of porosity in the composites. This provides strong evidence for the crosslinking effect of the 9DMAP-PhA dendritic proton conductor, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 22a. Interestingly, the composite with x = 300% exhibited a smaller BET surface area compared to x = 50 and 75. Additionally, pores with a diameter of about 5 nm were confirmed at x = 50 and 75, but not at x = 300. This suggests that the smaller pore size observed at x = 300 is due to the higher composition ratio of the 9DMAP-PhA crosslinker, which likely results in the division into smaller pores (Supplementary Fig. 22b). These findings support the hypothesis that 9DMAP-PhA functions as a crosslinker in polymeric Cell-SA, contributing to its unique structural and morphological properties.

Figure 2d depicts the temperature dependence of proton conductivity in 9DMAP-PhA, Cell-SA, and Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA composites with varying composition ratios (x = 10, 25, 50, 75, 300 mol%) under anhydrous conditions. Pristine Cell-SA exhibited the highest proton conductivity (2.48 × 10−3 S cm−1) at 100 °C but showed no proton conductivity above this temperature due to its decomposition near 100 °C. The incorporation of the 9DMAP-PhA dendritic proton conductor extended the temperature range of proton conductivity to 140 °C, highlighting the role of 9DMAP-PhA in improving thermal stability. The Proton conduction mechanism of the composites was analyzed using the Arrhenius equation to calculate their activation energy (Ea). Ea values for the Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA composites were 0.71, 0.90, 1.14, 0.96 and 1.00 eV for x = 300, 75, 50, 25 and 10, respectively, following the Vehicle mechanism3. These findings suggest that 9DMAP-PhA serves as a crosslinker in the composite, with its pyridinium nitrogen site interacting with PhA and its dimethylamino group interacting with Cell-SA. Interestingly, higher 9DMAP-PhA loading resulted in greater proton conductivity, whereas low-loading samples (x = 10–50) exhibited significantly decreased proton conductivity. The composite with the highest 9DMAP-PhA loading (Cell-SA@300%9DMAP-PhA) exhibited the best proton conductivity of 1.28 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 140 °C. This trend is explained by the trifunctional nature of Cell-SA, which allows up to three 9DMAP-PhA molecules to bind per reacting unit. In x = 300% composites, the mixing molar ratio of Cell-SA:9DMAP-PhA is exactly 1:3, maximizing crosslinking and enabling efficient proton conduction. This suggests that the higher the number of cross-linking 9DMAP-PhA molecules to Cell-SA contributes to the more efficient proton conduction. Moreover, the dimethylamino group of DMAP may enhance the proton dissociation of both the sulfonate groups of Cell-SA and phytate salt interacting with the pyridine group in DMAP. In contrast, at a lower loading ratios (x = 10–50), the 9DMAP-PhA crosslinker can act as a structural inhibitor, disrupting the formation of efficient proton conduction channels. The low concentration of acid groups per unit volume leads to a lack of proton-conducting channels, especially in harsh anhydrous conditions where H2O molecules, typically acting as intermediate proton-conducting carriers, are absent. Additionally, the relatively large molecular size of 9DMAP-PhA prone to induce gaps between conducting polymers (Cell-SA), resulting in further hindering proton conductivity. Based on these results, 9DMAP-PhA acts as dendritic proton-conducting crosslinker, providing multiple advantages, including improved thermal resistance and enhanced proton conductivity, particularly at optimum composition ratios. To further evaluate its performance, proton conductivity was measured under varied humidified conditions (40–95 %) at a stable temperature of 80 °C for Cell-SA@300%9DMAP-PhA. As a result, Cell-SA@9DMAP-PhA exhibited the remarkably high proton conductivity across a wide humidity range, whereas pristine Cell-SA showed reduced proton conductivity in high humidity region, likely due to the hydrolysis of crystalline cellulose under strong acidic conditions37.

In nutshell, the 9DMAP-PhA dendritic proton-conducting crosslinker not only enhances thermal stability and proton conductivity under high-temperature anhydrous conditions but also introduces a novel chemical approach. This approach involves double salt-salt crosslinking using strong basic molecules with multiple protonation sites, providing a new strategy for performance enhancement in PEMs through crosslinking, with potential applications in further material development.

Conclusions

Dendritic PhA-based salt proton-conducting materials were de novo developed as proton-conducting crosslinkers for PEMs. Among the series of phytates functionalized with pyridine-based molecules, DMAP was identified as the optimal candidate in terms of thermal stability. In particular, dendritic phytates containing nine of DMAP units (9DMAP-PhA) exhibited superior proton conductivity under anhydrous conditions compared to 6DMAP-PhA, probably due to the greater number of activated protonic acid sites derived from the interaction of PhA with DMAP. Although Cell-SA, proton-conducting polymer, suffers from insufficient thermal stability for high-temperature PEM applications, its composites with 9DMAP-PhA exhibit improved thermal stability up to 200 °C, suggesting the role of 9DAMP-PhA as heat resistance improver. Experimental and computational investigation revealed that the dimethylamino groups in the edge of 9DMAP-PhA also function as a basic site that forms ionic interactions with the sulfonic acid groups of Cell-SA. This interaction enables the formation of crosslinking between 9DMAP-PhA and Cell-SA polymer. In addition, Cell-SA@9DMAP-PhA composites presented enhanced proton conductivity at elevated temperatures above 100 °C, which bare Cell-SA cannot achieve due to decomposition. The composite with 300 mol% of 9DMAP-PhA showed a highest proton conductivity of 1.28 × 10−3 S cm−1 at 140 °C. These findings confirm that 9DMAP-PhA, as a dendritic proton-conducting crosslinker, provides multiple merits, such as an improved thermal stability and enhanced proton conductivity under high-temperature anhydrous conditions. Beyond these functional improvements, the development of 9DMAP-PhA-based crosslinkers introduces a novel chemical strategy, leveraging double salt-salt crosslinking via strong basic molecules with multiple protonation sites. This innovative approach not only enhances the performance of PEMs but also opens new possibilities for the development of advanced materials. The versatility of the DMAP-PhA crosslinker has potential applications beyond Cell-SA and can be utilized with other acid-modified PEMs, such as Nafion. Future research should include not only comprehensive characterization of these cross-linkers but also their evaluation within actual fuel cell systems.

Methods

Synthesis of dendritic-like Phytic acid conductors as 6Py-PhA, 6MeOPy-PhA,, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA

One milliliter water solution of phytic acid (50 wt%) was added to a MeOH solution (5 mL) of respective base materials (pyridine:3 mmol, 4-methoxypyridine:3 mmol, 4-di(methylamino)pyridine:3 mmol, or 4-di(methylamino)pyridine: 4.5 mmol for 6Py-PhA, 6MeOPy-PhA, 6DMAP-PhA, and 9DMAP-PhA, respectively) in a 10 mL sample tube, and the tube was stirred at room temperature overnight. The reaction mixture retained its transparency. The reaction mixture was poured into THF (500 mL) and the resulting precipitate was collected by filtration, washed with THF and diethyl ether, and dried at room temperature under vacuum.

Synthesis of cellulose sulfonic acid (Cell-SA)

Cellulose sulfonic acid was prepared by adding chlorosulfonic acid (6.2 mL, density-1.75 g cm−3, 92.51 mmol) and Chloroform (10 mL) dropwise to a stirred mixture of cellulose (5.00 g, MW-162.14 g mol−1) in n-Hexanes (50 mL) at 5 °C for 2 h. After complete addition, the mixture was stirred for additional 2 h until HCl was removed from the reaction vessel. The mixture was filtered, washed with methanol, and dried at room temperature to obtain cellulose–SO3H.

Synthesis of cell-SA@9DMAP-PhA composite

To synthesize composites of Cell-SA@10%9DMAP-PhA, begin by dispersing 0.4 g of Cell-SA and 10% (vs Cell-SA) (0.1706 g) of 9DMAP-PhA in 5 mL of DD-water and stirring overnight. Subsequently, wash the resultant solution of the composite with THF several times and vacuum dry it at room temperature, resulting in Cell-SA@9DMAP-PhA 10% composite in the form of white powder. Repeat the process with varying amounts of 9DMAP-PhA to obtain Cell-SA@x%9DMAP-PhA (x = 25, 50, 75, and 300). The detailed information of the synthesis and characterization are provided in the Supplementary information.

Responses