Depth heterogeneity of lignin-degrading microbiome and organic carbon processing in mangrove sediments

Introduction

Mangrove ecosystems occupy a mere 0.5% of the global coastal area but contribute 10–15% (24 Tg C yr−1) to coastal sediment carbon (C) storage1. Their disproportionate contribution to C storage is closely linked to the rich lignocellulosic detritus, which has been thought of as a quantitatively significant source of particulate organic matter in mangrove sediments2. Lignin, the most underutilized fraction of lignocellulosic detritus, was slowly degraded in mangrove sediments due to its inaccessibility to most microbes. The half-life of lignin derived from mangrove leaf litters was ∼150 yr in the upper 1.5 m of the sediments3. However, during mangrove inundation, lignin decay also occurred via propyl side chain oxidation and aromatic ring cleavage in aerated thin sediment surface layers3. This not only has important implications for the biospheric cycling of C from this abundant biopolymer but also leads to the alteration of organic C storage in mangrove sediments4. Consequently, understanding the fate and decomposition of lignin is crucial for accurately estimating the blue C potential of mangrove ecosystems.

Lignin decomposition is thought to proceed via two stages: depolymerization of native lignin, and mineralization of lignin-derived heterogeneous low-molecular-weight aromatics, i.e., lignin monomer derivatives (LMDs)5,6. For the depolymerization of native lignin, one of the most frequently identified and studied enzymes is laccase, which oxidizes phenolic lignin using molecular O2 as an electron acceptor7. The major laccase-producing bacterial taxa in mangroves sediments included Proteobacteria, Actinobacteria, and Bacteroidetes8. Although archaeal laccases remain unknown in mangroves ecosystems, genes coding laccase-like enzymes have been only identified in Halobacteria9, a dominant archaeal lineage in the mangrove archaeal community10. For the LMDs’ mineralization, Alphaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria were generally thought to be the main participants via ring cleavage pathways6, while Bathyarchaeota was reported to grow with lignin as an energy source11. To adapt to O2 fluctuations, the LMDs’ mineralization showed different adaptation strategies to O2 availability, including aerobic, low O2, or anaerobic pathways6,12. Although part of lignin degraders has been reported in mangrove sediments8,13, their related pathways for lignin decomposition and their adaption to O2 fluctuations remain largely unclear.

Mangrove sediments are primarily anaerobic, topped by a slim layer of aerobic sediments14. Most of lignin-related studies have so far focused on the surface sediments (i.e., 0–20 cm)8,13,15,16. However, a major portion corresponding to around 92.4–97.5% of annual detritus accumulation was from fine roots17, which extended to depths exceeding 100 cm18. Furthermore, compared to the surface sediments, the subsurface sediments were more anoxic19,20. Previous experiments with radiolabeled lignin demonstrated that lignin was also biodegradable to CO2 in the absence of O221. Further evidence on the anaerobic biodegradation of chemically modified lignin and a lignin-related dimer with the β-aryl ether bond throws doubt upon the requirement of O2 for polymer cleavages22,23. These previous findings, therefore, allow us to hypothesize whether the more anoxic and highly reducing condition in mangrove subsurface sediments would lead to the distinctive lignin degraders, as do the pathways for lignin decomposition.

In light of the high complexity of lignin decomposition24 and the low cultivability of microbes25, fully elucidating the lignin degraders and their involved process in mangrove sediments has become a challenge for researchers. Fortunately, the continuous advancement of microbial genomics technologies (i.e., 16S rRNA gene amplicon and metagenomic sequencing) enables the unraveling of microbial dark matter and allows prediction about its functionality related to lignin decomposition7,26 in mangrove sediments. Taking the aerobic mineralization pathway of lignin derivatives as an example, protocatechuate (PCA) 4,5-ring cleavage pathway was found to be performed by Gammaproteobacteria and Deltaproteobacteria through metagenomic sequencing26. In parallel with advances in sequencing technology and bioinformatic techniques, genome-centric metagenomic analysis of microbial communities will provide the necessary information to examine how specific microbial lineages participate in lignin decomposition and whether they exhibit genomic and metabolic heterogeneity across sediment depths.

Here, we hypothesized that microbe-mediated C storage mechanisms within mangrove ecosystems exhibited vertical differentiation. This variation might arise from the environmental preferences of functional microbes engaged in lignin metabolism, such as their adaptation to O2 availability at different depths. Specifically, in deeper sediments, we anticipated the presence of distinctive lignin-degrading microbial communities and associated degradation pathways that are specialized for O2-deficient conditions. To test these hypotheses, we sampled five 100-cm mangrove sediment cores with ten layers in Kandelia obovata, Qi’ao Island, a less disturbed natural reserve27. By measuring the lignocellulosic content and conducting microbiome analysis, our study provided a metagenome-centric insight into the microbe-driven lignin metabolism across the 100-cm mangrove sediments, which significantly expanded the diversity of lignin degraders and their metabolism pathways and promoted the cognition of the blue C sink.

Results

The vertical pattern of lignocellulose content and CAZyme-coding gene abundance in mangrove sediments

To examine the fractions of lignocellulosic detritus and their vertical pattern in mangrove sediments, we measured the contents of cellulose, hemicellulose, and lignin across five 100-cm mangrove sediment cores. Our results revealed that among these three lignocellulosic components, the content of lignin was the highest (29.61–67.26 g/kg), followed by hemicellulose (0.73–1.78 g/kg), and cellulose (0.20–1.26 g/kg) (Fig. 1a). With the increase of sediment depth, their contents all showed a decreasing trend. The lignin consistently kept a high proportion (95.0–97.7%) of the total lignocellulose content, revealing its dominance in lignocellulosic detritus of mangrove sediments.

a The variations of lignocellulose content in the mangrove sediment cores. The values on the bar chart represent the percentage of lignin content in the total lignocellulose content. b The variations of CAZyme-coding gene abundance in the mangrove sediment cores. GH glycoside hydrolase, PL polysaccharide lyase, CE carbohydrate esterase, GT glycoside transferase, CBM carbohydrate-binding module, AA axillary activity enzyme. c The hierarchical clustering of samples based on the mean abundance of each CAZyme family gene. d The variations of AA family gene abundance in the mangrove sediment cores. Statistical analysis was performed using t-test analysis. The values on the bar chart represent the percentage of AA family gene abundance in the total CAZyme-coding gene abundance.

Next, we investigated the potential for the enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic detritus in mangrove sediments, and a total of 408 CAZyme families were identified. Among the six classes of CAZyme-coding genes, the Auxiliary Activity (AA) family genes, particularly relevant to lignin breakdown28, only accounted for 1.24–1.98% of the CAZyme-coding gene abundance (Fig. 1b, d), corroborating the high proportion of lignin in lignocellulosic detritus of mangrove sediments (Fig. 1a). Based on the gene abundance of each CAZyme family, our hierarchical clustering of samples at different depths revealed two main clusters (Fig. 1c): the surface (0–20 cm) and subsurface (20–100 cm) sediments. Notably, the abundance of AA family genes in the surface was significantly higher than that in the subsurface (t-test, p < 0.0001; Fig. 1d), consistent with the significantly higher content of lignin in the surface sediments (t-test, p < 0.01; Supplementary Fig. 1). As phenolic lignin, comprising <20% of the lignin polymer, is the primary substrate for these enzymes29, while non-phenolic lignin is nearly impossible to degrade30, surface sediments likely demonstrate greater lignin degradation potential. The abundance of AA family genes has been shown to correlate with lignocellulose degradation rates31, lignin-degrading enzyme protein abundance32, and lignocellulose-degrading enzyme activity33. Thus, surface sediments likely experience more extensive lignin degradation compared to subsurface sediments, leading to an accumulation of non-phenolic fragments and phenolic derivatives33.

Depth stratification of lignin-depolymerizing genes and microbes in mangrove sediments

The lignin and its derivatives can be degraded by a range of microbes via depolymerization and mineralization6, two key processes substantially influencing the quantity and quality of the organic C pool sequestered in sediments2. The initial degradation step for lignin is its depolymerization into low-molecular-weight aromatic compounds by lignin-depolymerizing enzymes. Thus, we first investigated the lignin-depolymerizing genes and involved microbes, as well as their vertical pattern across the mangrove sediment cores.

Among the AA subfamily, AA1 (laccases, EC 1.10.3.2) and AA2 (class II peroxidases: manganese peroxidase (MnP, EC 1.11.1.13), lignin peroxidase (LiP, EC 1.11.1.14) and versatile peroxidase (VP, EC 1.11.1.16)) are thought as the typical lignin depolymerases28. Through metagenomic analyses, we only detected the presence of AA1 (laccases)-related genes in our samples, with significantly higher abundance in the surface than that in the subsurface sediments (t-test, p < 0.0001; Supplementary Fig. 2a). Together with the predominance of AA1 family among all identified AA families (Supplementary Data 1), our results indicate that the laccases-related AA1 family was mainly responsible for lignin depolymerization in mangrove sediments. Through examining the phylogenic taxonomy of the dominant AA1 family genes, we found both bacterial and archaea were potential lignin depolymerizers. However, their relative abundance in potential lignin depolymerizers differed across the sediment cores. Although the majority of lignin-depolymerizing genes (80.7–100.0%) in the surface were derived from bacteria, the archaeal relative abundance in potential lignin depolymerizers increased with depth and accounted for 35.2–48.5% in the subsurface (Supplementary Fig. 2b). Specifically, many AA1-related microbial lineages showed a notable variation in their relative abundance in potential lignin depolymerizers between surface and subsurface sediments. Zetaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, and Betaproteobacteria showed a greater relative abundance in potential lignin depolymerizers in the surface sediments, whereas Chloroflexi, Zixibacteria, Planctomycetes, Thorarchaeota, and Bathyarchaeota displayed an elevated relative abundance in potential lignin depolymerizers in the subsurface sediments (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Supplementary Fig. 2c). However, AA1-carrying Deltaproteobacteria and Euryarchaeota, as the dominant bacterial and archaeal members responsible for lignin depolymerization, showed no significant relative abundance difference in potential lignin depolymerizers between surface and subsurface sediments (LEfSe, LDA < 2; Supplementary Fig. 2c, d), indicating their consistent relative abundance in potential lignin depolymerizers across the sediment cores.

Depth stratification of LMDs’ mineralization genes in mangrove sediments

As another important process of lignin degradation, LMDs can be mineralized through multiple mineralization pathways6,12. Through our metagenomic analysis, we identified genes involved in nine major mineralization pathways of LMDs in mangrove sediments. These pathways can be categorized into three strategies based on their O2 dependence12: five aerobic pathways, two low O2 pathways, and two anaerobic pathways (Supplementary Fig. 3). Notably, these pathways adapt to different O2 levels. For instance, the oxidation of equivalent benzoate requires less O2 in the low O2 pathway than in the aerobic pathway, while the anaerobic pathway does not require any O₂, as described in Eqs. (1)–(3) (Fig. 2a). The first step for all these mineralization pathways is ring cleavage, which is of paramount importance as it requires overcoming substantial resonance energy to destabilize the aromatic ring12. By comparing the abundance of ring cleavage genes, we found that across the mangrove sediment cores, the most abundant genes were bcrABCD (386.5 TPM) involved in the anaerobic ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway, followed by bamBC (108.5 TPM) involved in the anaerobic ATP-independent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway, paaABCDE (98.9 TPM) involved in the low O2 phenylacetyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway and catE/dmpB (96.2 TPM) involved in the aerobic catechol 2,3-ring cleavage pathway (Supplementary Fig. 3). Furthermore, discriminative LEfSe analysis revealed that many ring cleavage genes for the aerobic and low O2 pathways (i.e., pcaGH, ligAB and desB in the aerobic pathways; boxAB in the low O2 pathways) and further transformation genes (i.e., pcaIJ, ligC, ligI, ligJ, dmpH and mhpD in the aerobic pathways; paaG, paaZ, paaF and boxC in the low O2 pathways) were significantly enriched in the surface (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 2a, b). In contrast, all ring cleavage genes (i.e., bcrABCD and bamBC) and one transformation gene (had) for the anaerobic pathways were significantly enriched in the subsurface (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 2a, b). These results indicate that distinct depth-stratified patterns of multiple O2-dependent-strategy mineralization pathways ensure the LMDs’ biodegradability at varying depths of mangrove sediments.

a The difference between aerobic, low O2, and anaerobic pathways: the mineralization of benzoate as an example. b Depth heterogeneity of gene abundance for LMDs’ mineralization pathways between the surface and subsurface sediments. The ring cleavage genes in LMDs’ mineralization pathways were highlighted in bold. Differences in gene abundances between the surface and subsurface sediments were determined with LEfSe, using a threshold of 2.0 for logarithmic linear discriminant analysis scores.

Multiple bacterial LMDs’ mineralization pathways in mangrove sediments

Since lignin depolymerization occurs extracellularly, we examined the taxonomic origin of AA1 family genes to identify the functional microbes (Supplementary Fig. 2). By contrast, the LMDs’ mineralization is an intracellular process that requires the co-metabolism of multiple genes; thus, the MAGs-based analysis seems more reasonable to explore the functional microbes involved in the LMDs’ mineralization. In this study, we obtained a total of 49 MAGs containing a nearly full set of genes for mineralizing LMDs, with completeness higher than 70% and contamination less than 10% (Fig. 3; Supplementary Data 2). Based on the taxonomic classifications of the GTDB-tk tools, these MAGs were assigned to nine bacterial lineages: Pseudomonadota (15), Chloroflexota (13), Desulfobacterota (7), Acidobacteriota (5), Zixibacteria (4), Myxococcota (2), Bacteroidota (1), Gemmatimonadota (1) and KSB1 (1). Of them, Pseudomonadota, Chloroflexota, Desulfobacterota, and Acidobacteriota were extensively reported as members of the LMDs’ mineralization6,34,35, whereas Zixibacteria, Myxococcota, Bacteroidota, Gemmatimonadota, and KSB1 were rarely reported on this function. Interestingly, many MAGs belonging to Zixibacteria and Myxococcota were characterized by their significant enrichment in the subsurface sediments (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 3), and even one Zixibacteria MAG (MAG023) was the dominant subsurface-enriched member (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the mangrove subsurface sediments serve as a promising source for broadening the repertoire of functional bacteria responsible for the LMDs’ mineralization.

The tree was constructed based on the concatenated alignment of bacterial 120 conserved single-copy marker genes extracted with GTDB-Tk. Taxonomic classifications of MAGs are labeled by different colors. Except for Gammaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria at the class level, other bacterial lineages are at the phylum level. The abundance and function of different bacterial lineages are separated by dashed lines. Differences in the relative abundance of MAGs between the surface and subsurface sediments were determined with LEfSe, using a threshold of 2.0 for logarithmic linear discriminant analysis scores. Gene presence and absence were determined by MAG-based functional analysis. Gene presence is indicated by filled squares and gene absence by open squares. BCA benzoyl-CoA, PCA protocatechuate, GA gallate, PHAs polyhydroxyalkanoates, BCR benzoyl-CoA reductase.

Unique bacterial lineages participating in the LMDs’ mineralization were respectively detected in surface or subsurface sediments. In Pseudomonadota with multiple LMDs’ mineralization pathways, MAGs belonging to the alphaproteobacterial Pseudolabrys and gammaproteobacterial Burkholderiales (SG8-39 family) exhibited significant enrichment in the surface (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 3). On the contrary, in Zixibacteria exclusively possessing the ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway, most MAGs were significantly enriched in the subsurface (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 3). Although members within the same bacterial lineage tended to share similar LMDs’ mineralization pathways, their distribution patterns could vary greatly. Desulfobacterota MAGs shared the anaerobic ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway and ATP-independent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway but exhibited different distribution patterns. For instance, within the three Desulfobacterales MAGs, MAG013 and MAG014 belonging to JAHEIW01 family were significantly enriched in the subsurface, while MAG034 belonging to UBA2174_A family was significantly enriched in the surface (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 2). Furthermore, within the Chloroflexota phylum, seven MAGs belonging to Fen-1058 family commonly contained the low O2 phenylacetyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway and the aerobic catechol 2,3-ring cleavage pathway, but their distribution patterns were also inconsistent (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Data 2). Except one MAG (MAG030) with no significant difference in distribution (LEfSe, LDA < 2; Fig. 3), one MAG (MAG032) and five MAGs (MAG008-012) were significantly enriched in the surface and the subsurface, respectively (LEfSe, LDA ≥ 2; Fig. 3). These findings highlight that the LMDs’ mineralizing bacterial lineages enriched in the surface or subsurface sediments could employ aerobic, low O2, or/and anaerobic O2-adaptive strategies to cope with the redox fluctuation in mangrove sediments.

Based on their functional properties, we termed these functional bacteria as “processing plants” for LMDs in mangrove sediments, with two major “end products”. The one is “waste”, represented by CO2. The other is “high-quality product”, represented by biomass (e.g., polyhydroxyalkanoate, PHA36,37). Given that different bacterial lineages usually contained different mineralization pathways, we raised the question of whether different bacterial lineages showed variations in their biomass production capacity. To answer this question, we analyzed the PHA synthesis genes (phaE or phaC) within these 49 MAGs and found that nearly all 15 Gamaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria MAGs harbored PHA synthesis genes (Fig. 3). In Alphaproteobacteria, the Pseudolabrys and Rhodoplanes members were identified to carry phaC. The Gamaproteobacteria members carrying phaE or phaC mainly belonged to four orders: Acidiferrobacterales, Burkholderiales, Chromatiales, and Steroidobacterales (Supplementary Data 2). With the exception of three low-abundance MAGs (MAG021, MAG008, and MAG011), all the remaining 31 MAGs lacked PHA synthesis genes. These findings suggest that the surface-enriched Alphaproteobacteria and Gamaproteobacteria members may have great biomass production capacity (GBPC).

Besides biomass production capacity, the production rates of biomass for these “processing plants” are also related to their production scale and speed, equivalent to microbial abundance38 and growth rate39,40, respectively. We further wondered whether there were differences in the production rates between the surface-enriched and subsurface-enriched “processing plants”. To answer this question, we selected the two most abundant representative MAGs from both surface and subsurface-enriched MAGs (surface-enriched representatives, Gammaproteobacteria MAG044, and Chloroflexota MAG032; subsurface-enriched representatives, Chloroflexota MAG004, and Zixibacteria MAG023) to analyze their abundance and predicted growth rates. Among these four “processing plants”, only Gammaproteobacteria MAG044 with the PHA synthesis gene had GBPC, while others without PHA synthesis genes had low biomass production capacity (LBPC). Our comparative analysis revealed that the abundance of the first two MAGs in the surface and the latter two MAGs in the subsurface was similar (one-way ANOVA, P > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 4), implying their comparable production scale. However, MAG044 exhibited a significantly higher predicted growth rate on the surface than MAG023 and MAG004 in the subsurface (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 4), implying the higher production speed of the GBPC member on the surface than that of the LBPC members in the subsurface sediments. Conversely, the production speed of the LBPC member on the surface was similar to that of the LBPC members in the subsurface (one-way ANOVA, P > 0.05; Supplementary Fig. 4). Together, these results suggest that surface-enriched bacteria possess a greater capability for converting LMDs into biomass than subsurface-enriched bacteria, which tend to employ a “slow processing” strategy to decelerate lignin-derived C degradation.

Expanded anaerobic respiratory pathways supporting the anaerobic LMDs’ mineralization in mangrove sediments

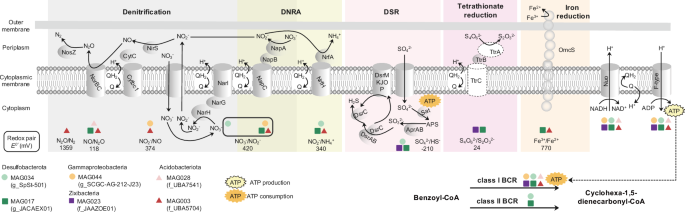

Given that the anaerobic mineralization of LMDs was an energy-consuming process41, we analyzed anaerobic respiratory pathways in six representative MAGs with a nearly full set of genes for this progress (Gamaproteobacteria MAG044, Desulfobacterota MAG 017 and MAG 034, Acidobacteriota MAG003 and MAG028, and Zixibacteria MAG023). These MAGs were highly abundant in each involved bacterial lineage, with high genomic quality (completeness ≥ 90%; contamination ≤ 5.5%) (Supplementary Data 2). The two anaerobic LMDs’ mineralization pathways were specifically investigated and differed by the ring cleavage genes coding benzoyl-CoA reductase (BCR): bcrABCD coding class I BCR (ATP-dependent) and bamBC coding class II BCR (ATP-independent)12. Functional annotation revealed that all six representative MAGs contained genes coding class I BCR, in which two Desulfobacterota MAGs simultaneously possessed genes coding class II BCR (Fig. 4). When screening the potential of anaerobic respiratory pathways providing energy for the LMDs’ mineralization, we found that these representative class I and class II BCR MAGs contained genes related to denitrification, dissimilatory sulfate reduction (DSR), dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia (DNRA), tetrathionate respiration, or Fe III respiration (Fig. 4). It is worth noting that only the denitrification respiration was commonly reported in class I BCR bacteria12,42, but the latter four respiratory pathways had never been demonstrated. Although bacteria with class II BCR can use aromatic substrates for growth through DSR, Fe III respiration, or fermentation43, the two Desulfobacterota MAGs constructed in this study had the additional potential to couple DNRA and tetrathionate respiration with class II BCR.

DNRA dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonia, DSR dissimilatory sulfate reduction, BCR benzoyl-CoA reductase. Key enzymes include: nitrate reductase (NarGH/NapAB), nitrite reductase (NirS/NrfA), nitric oxide reductase (NorBC), nitrous-oxide reductase (NosZ), dissimilatory sulfite reductase (DsrABC), tetrathionate reductase (TtrABC), hexaheme cytochrome polymer (OmcS); respiratory elements: NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (Nuo), F-type ATPase, cytochrome bc1 complex (Cytbc1), cytochrome c (CytC). Protein presence in the representative MAGs is indicated by a solid line of the edge and protein absence by a dotted line. Circles: MAGs significantly enriched in the surface; squares: MAGs significantly enriched in the subsurface; triangles: MAGs with no significant distribution difference between the surface and subsurface sediments. Differences in the relative abundance of MAGs between the surface and subsurface sediments were determined with LEfSe, using a threshold of 2.0 for logarithmic linear discriminant analysis scores.

Among these six representative MAGs, MAG003, MAG 017 and MAG 034 coded genes not only for denitrification (i.e., napAB, narGH, nirS, norBC, nosZ), but also for DNRA, DSR, tetrathionate respiration, or Fe III respiration (Fig. 4; Supplementary Data 3). The co-occurrence of various anaerobic respiratory pathways covering denitrification in these three MAGs means that we cannot rule out the possibility that they rely solely on denitrification to provide energy for the anaerobic mineralization of LMDs. Thus, we wondered if there were bacteria would anaerobically mineralize LMDs by alternative respiratory pathways instead of the denitrification. As expected, we found that MAG023 with class I BCR, did not possess any genes for denitrification but contained genes coding DSR and tetrathionate respiration (i.e., sat, aprAB, dsrABDMKJOP, and ttrB) (Fig. 4; Supplementary Data 3). Our results imply that the Zixibacteria member had the potential for anaerobically mineralizing LMDs through DSR- or tetrathionate-respiration- coupled class I BCR, expanding anaerobic respiratory pathways supporting the anaerobic LMDs’ mineralization.

Overlooked archaea-driven LMDs’ mineralization pathway in mangrove sediments

Given the increased relative abundance of archaeal members (Bathyarchaeota and Thorarchaeota) in potential lignin depolymerizers within the subsurface, we also used metagenomic binning to generate archaeal MAGs and analyzed their LMDs’ mineralization pathway. Among 104 generated archaeal MAGs, 25 MAGs contained at least one gene of bcrABCD involved in the anaerobic ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway (Fig. 5; Supplementary Data 4). Notably, 68% of bcrABCD-carrying MAGs were assigned to the order B26-1 in Bathyarchaeota, with additional genes for further transformation of dienoyl-CoA to 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA, i.e., those coding 6-oxo-cyclohex-1-ene-carbonyl-CoA hydrolase (oah) and 6-hydroxycyclohex-1-ene-1-carbonyl-CoA dehydrogenase (had) (Fig. 5; Supplementary Data 4). Considering that previous studies reported sedimentary Bathyarchaeota enrichment under lignin-feeding11 but focused on O-demethylation of lignin side chains (–OCH3)44, we provide additional genomic evidence that Bathyarchaeota had the genetic potential for the LMDs mineralization focusing on aromatic ring cleavage, expanding its metabolic mechanism of lignin-derived C degradation.

The tree was constructed based on the concatenated alignment of archaeal 53 conserved single-copy marker genes extracted with GTDB-Tk. Taxonomic classifications of MAGs are labeled by different colors. Gene presence and absence were determined by MAG-based functional analysis. Gene presence is indicated by filled squares and gene absence by open squares. Black squares represent genes for the anaerobic ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway (benzoyl-CoA to 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA) and gray squares represent genes for the transformation of 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA into acetyl-CoA. The archaeal abundance in the surface and subsurface sediments are separated by a dashed line. The completeness of MAGs was evaluated by CheckM (see Supplementary Data 4 for details).

However, all of these B26-1 MAGs did not contain the full set of genes for the transformation of 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA into acetyl-CoA, and neither did the other remaining archaeal MAGs. In view of the low completeness (an average of 67.2%, 52.6–93.7%) of our generated B26-1 MAGs (Fig. 5; Supplementary Data 4), we downloaded 112 reference genomes from the GTDB database with high completeness (an average of 88.7%, 50.5–99.1%) (Supplementary Data 5) and performed functional annotation to examine their metabolism potential. Consistent with our MAGs’ annotation results, we also did not find any reference genomes with the full set of genes for the transformation of 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA into acetyl-CoA. In particular, as reported to utilize lignin for growth in Bathyarchaeota11, the BA1 family members possessed genes for the anaerobic ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway, but lacked the full set of genes for the transformation of 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA into acetyl-CoA (Supplementary Fig. 5). These results suggest the possibility of an unexplored genetic landscape for the transformation of 3-hydroxypimelyl-CoA in this archaeal lineage, awaiting further investigations.

From the perspective of abundance, the abundance of archaea in the metagenome was very low, only 0.92–2.53%, compared with bacteria (57.59–71.65%) (Supplementary Fig. 6). Also, the abundance of archaeal MAGs containing bcrABCD genes was significantly lower than that of other archaea (t-test, P < 0.0001; Supplementary Fig. 7), indicating a limited role of archaea in the LMDs’ mineralization of mangrove sediments.

Discussion

In the surface sediments, we found that many Gammaproteobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria and Chloroflexota members possessed a broad range of O2-adaptive strategies for mineralizing LMDs, such as the aerobic PCA 3,4/4,5-ring cleavage pathways, the low O2 benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway, and the anaerobic ATP-dependent benzoyl-CoA ring cleavage pathway. Such a broad range of O2-adaptive strategies for mineralizing LMDs could enable these functional microbes to survive under the rapid changes in redox conditions, induced by tidal wetting and drying in mangrove surface sediments45. This microbial adaptation to a high hydrological regime was also found in the dynamic estuarine ecosystem, where Rhodococcus and WPS-2 members exhibited multiple O2-adaptive growth modes46. Further controlled lab experiments confirmed the conjunctive use of aerobic and anaerobic respiration in Acidobacterium when simulating aerobic and anaerobic cycling47.

Contrary to the versatile strategies of the surface-enriched microbes, the anaerobic subsurface-enriched microbes participated in the LMDs’ mineralization mainly via the anaerobic benzoyl-CoA pathway with class I BCR. Despite hypoxia, the specific benzoyl-CoA pathway performed by subsurface-enriched microbes could be supported by an elevated diversity of electron acceptors48. Apart from previously recognized denitrification12, our genomic annotation showed that the subsurface-enriched bacteria coding class I BCR (i.e., Zixibacteria, Acidobacteriota, and Desulfobacterota) also exhibited genetic potential for DSR, DNRA, tetrathionate respiration, as well as Fe (III) respiration. The biodegradation of lignin under sulfate-reducing conditions was reported in an anaerobic reactor49, and some Desulfobacterota grew on aromatic compounds with the support of DSR respiration43. Under anaerobic conditions, the reduction of Fe (III) could occur concurrently with the oxidation of organic matter, while the tetrathionate respiration allowed the utilization of non-fermentable C sources in microaerophilic Campylobacter jejuni50,51. Furthermore, DNA-stable isotope probing proposed DNRA respiration as a novel energy source for anaerobic ring cleavage of aromatic compounds in Aromatoleum from 2 to 5 m soil52,53. Together, our findings provide genetic evidence that subsurface-enriched microbes could use an elevated range of electron acceptors to anaerobically mineralize LMDs in mangrove sediments.

Microbe-driven lignin metabolism exerts a notable impact on organic C sink in mangrove sediments39; however, the underlying mechanisms are still complicated. As the traditional theory of wetland C sink, the “enzymatic latch” mechanism4 posits that the core of sediment organic C storage is primarily derived from plants. In this study, we found that genes for aerobic lignin depolymerization and LMDs’ mineralization pathways were enriched in the surface sediments (Supplementary Fig. 2; Fig. 2), indicating a high O2 availability. It was reported that the high O2 availability could noticeably enhance the activity of phenol oxidase, further stimulating the cellulose and hemicellulose degradation4,54. This was because the elevated phenol oxidative activity eliminated the phenolic lignin that was toxic to hydrolysis enzymes for the degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose. We, therefore, propose that the “enzymatic latch” was weakened in the surface sediments with high O2 availability, thereby stimulating the microbial decomposition of plant-derived organic C, such as the cellulose and hemicellulose (Fig. 6). Compared with the surface sediments, the subsurface sediments were enriched in genes for anaerobic LMDs’ mineralization pathways (Fig. 2), indicating a low O2 availability. Based on the positive effect of O2 availability on the activity of phenol oxidase4,54, we point out the enhanced “enzymatic latch” in the subsurface sediments with low O2 availability, resulting in the less lignocellulosic biodegradation and the more plant-derived organic C storage (Fig. 6).

The “enzyme latch” was enhanced in the subsurface sediments due to a low O2 availability (e.g., subsurface-enriched genes for anaerobic LMDs’ mineralization pathways), resulting in less lignocellulosic biodegradation and more plant-derived organic C storage. However, the microbial CUE potential was higher in the surface sediments due to a high proportion of bacteria with great biomass production capacity (i.e., surface-enriched Gammaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria members), where microbe-derived organic C was important in the organic C pool.

Besides the “enzymatic latch” mechanism, the microbial CUE concept has also become increasingly popular as an integrative metric for capturing the balance of the loss and accumulation of soil organic C, defined as the C partitioning between microbial biomass and respiration55,56. By analyzing microbial metabolism related to CUE potential in mangrove sediments, we found that many lignin-degrading microbes, especially for surface-enriched Gammaproteobacteria and Alphaproteobacteria members, contained genes related to the production of intracellular C storage compounds (i.e., PHA). Interestingly, previous studies have shown that the maximum PHA content in microbial biomass positively correlates with the combined abundances of bacteria capable of PHA storage57. However, the subsurface sediments were enriched with very few microbes with this capacity (Fig. 3). This disparity suggests a potential depth-dependent variation in C storage mechanisms within the mangrove sediment profile. Furthermore, research in surface forest biomes has demonstrated that microbial functional genes involved in the decomposition of lignin, lipids, and aminosugars are positively correlated with microbial CUE58. Given that intracellular C storage capacity can enhance the microbial CUE36,59,60, we posit that surface sediments likely possess a greater CUE potential compared to subsurface sediments. Surface sediments, characterized by high O2 availability, provide ample energy for lignin-degrading microbes in growth metabolism and in vivo turnover of lignin-derived C, resulting in the deposition of microbial-derived C. In contrast, subsurface sediments, with limited O2, constrain the growth rates and in vivo turnover of lignin-degrading microbes, leading to increased storage of plant-derived C. Our findings elucidate microbial mechanisms driving C stock changes with sediment depth61. However, current research lacks direct evidence characterizing the contributions of those uncultured microbes to lignin-associated C storage in mangrove sediments, requiring the integration of microbial culture experiments and functional assays to further elucidate.

Given that over 80% of C in Chinese mangrove ecosystems resides within the top 100 cm of sediments62, our findings emphasize the imperative of elucidating the differential fate of lignocellulose across surface and subsurface sediments. Such insights are paramount for refining management strategies aimed at enhancing blue C sequestration, particularly amidst the backdrop of escalating global temperatures. The escalating phenomenon of global climate change, manifested in rising sea levels63, exacerbates the inefficiency of O2 diffusion in mangrove sediments, thereby impacting vertical stratification64. Drawing upon our observations regarding the pivotal role of O2 availability in modulating the mangrove C sink process, we propose a hypothesis that the elevated sequestration of plant organic C may occur, thus engendering a positive feedback loop with climate change. However, the validation of this hypothesis necessitates meticulous experimental design in future endeavors.

Methods

Sampling mangrove sediments

We conducted lignocellulose and microbial investigations of mangrove sediments in December 2019 at a sampling site situated in the Qi’ao Island Natural Reserve (22.42°N, 113.63°E), Zhuhai City, Guangdong province, China. The tidal pattern displayed irregular semidiurnal characteristics, with average levels of high tide at 0.17 m and low tide at −0.14 m27. We collected sediments partially exposed to air from the mangrove habitat of Kandelia obovate, a dominant and native species in the history of this site27. We obtained five replicate sediment cores, using a 1-m-long PVC sampling tube following the ebb phase, and sliced them into 10 consecutive depths (0–5, 5–10, 10–15, 15–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, 50–60, 60–80, and 80–100 cm), generating a total of 50 sediment samples. We stored these samples in portable coolers at 4 °C and transported them to the laboratory within 24 h for further treatments. Around 100 g sediments were kept at −80 °C for DNA extraction, and the rest of them were dried at 60 °C for lignocellulose content determination.

Lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose content analysis

The moisture content of each sample was determined after drying the sediments at 60 °C to a constant weight. The dried sediments were ground and passed through a 200-mesh sieve. For lignocellulose isolation, we weighed out 0.1–1.0 g of dry sifted sediments, as the previous study described65.

The acetyl bromide spectrophotometric method was used to determine the lignin content65,66. After lignocellulose isolation, we weighed out 1.0–1.5 mg of prepared cell wall material into 2.0 mL volumetric flask, leaving one tube empty for a blank. We added 300 μL of 25% v/v acetyl bromide in glacial acetic acid into the volumetric flask to dissolve lignin, and heated samples at 37 °C for 6 h. Next, we added 480 μL of 2.0 M sodium hydroxide and 210 μL of 0.5 M hydroxylamine hydrochloride into the volumetric flask. We vortexed samples well, and added glacial acetic acid into the volumetric flask to fill it up exactly to the 2.0 mL. After capping, inverting several times to mix, and centrifuging samples (10,000 rpm, 10 min) at room temperature, we pipetted 200 μL of supernatant into a UV-specific 96-well plate and measured the absorbance by a microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Fisher, USA) at 280 nm. The percentage of acetyl bromide soluble lignin in dried sediments was calculated through the following equation65 (4):

ABS: absorbance value; 0.539 cm: the path length; Coeff: 18.21; and Weight: mass (mg).

For the cellulose and hemicellulose content analysis, we added 0.5 mL of 2.0 M trifluoroacetic acid into the tube after lignocellulose isolation and heated samples at 100 °C for 6 h. Then we centrifuged samples at 10,000 rpm for 15 min. The supernatant was used to measure the hemicellulose content, and the precipitation was used to measure the cellulose content, as a previous study reported67. Each part was dried with nitrogen gas blow. We added 0.5 mL of isopropanol into the tube and vortexed samples to mix and evaporate to dryness. This step was repeated three times. Afterward we added 0.3 mL of 75% sulfuric acid into the tube. After mixing well, we left samples to stand at room temperature for 1 h. We added distilled water and samples into the volumetric flask to fill it up exactly to the 1.0 mL. We centrifuged samples at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. We transferred 100 µL of supernatant to a new 2.0 mL tube and added 200 µL of Anthrone Reagent (Anthrone dissolved in concentrated sulfuric acid, 2.0 mg anthrone mL−1 sulfuric acid) into the tube. We heated samples at 80 °C for 30 min and measured their absorbance by a microplate reader (Multiskan GO, Thermo Fisher, USA) at 625 nm. We prepared 0, 20, 40, 60, 80, and 100 µg mL-1 glucose standard solution for the standard curve line by the method above. The R² of the standard curve was 0.9993. The lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose contents in wet sediments were further calculated through their contents in dried sediments and the moisture content of related sediments.

DNA extraction and sequencing

The microbial community DNA was extracted from 5.0 g (0–20 cm), 10.0 g (20–60 cm), and 20.0 g (60–100 cm) of mangrove sediments. The extraction process utilized a combined protocol, incorporating both the sodium dodecyl sulfate extraction method68 and the Power Soil DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA, USA), as per the provided manual. Nanodrop ND-2000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was used to check the DNA purity, and the ratios of A260/A280 were about 1.8 with the A260/A230 above 1.7. Qubit 4 Fluorometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) was used to quantify the DNA concentrations. DNA fragment libraries were prepared with 1.0 μg of DNA and then subjected to metagenomic sequencing on Illumina Novaseq PE150 at Novogene (Tianjin, China) to generate paired-end reads. The basic information of the metagenomic sequencing reads was shown in Supplementary Data 6.

Metagenome sequence assembly and binning

After sequencing, the Read QC module within metaWRAP pipeline v1.3.069 was used to filter out the low-quality reads and human contamination, yielding clean reads. The microbial community composition, based on clean reads, was classified using Kraken2 v2.0.870, with the reference databases (NCBI_nt database) (parameter: -paired -use-names -use-mpa-style -report-zero-counts). The clean reads were assembled individually using MEGAHIT v1.1.3 within metaWRAP pipeline v1.3.069 and the contigs less than 1000 bp were removed. The remaining was binned and refined using the binning module (parameters: -maxbin2 -metabat2) and bin_refinement module. The refined metagenomic assembled genomes (MAGs) were reassembled using reassembled_bins module. The completeness and contamination of the reassembled MAGs were estimated by the lineage-specific workflow of CheckM v1.0.1271. MAGs from all metagenomes were dereplicated using dRep v3.4.072 to create a non-redundant MAG dataset (-sa 0.95 -nc 0.1). MAGs were classified via Genome Database Taxonomy Toolkit73 (GTDB-Tk, v2.1.0, release 214).

Contig-based functional and taxonomical analysis

Putative genes were called on assembled contigs for each sample using Prodigal74 (-p meta) and annotated against the dbCAN275 and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database76 using DIAMOND v2.0.1577 (parameter: blastx, -e 1e-5, -k 1). CAZyme-coding genes were annotated by dbCAN275. LMDs’ mineralization pathways were summarized from previous researches6,12 and related genes were collected from KEGG pathways (Supplementary Data 7). To estimate the relative abundance of putative genes in each sample, the TPM (transcripts per million) of each putative gene was calculated by Salmon v.1.6.078 via mapping to clean reads. The contigs were classified by MEGAN79 against NCBI-nr, and their coverage was calculated by Quast in metaWRAP pipeline v1.3.069.

MAG-based functional analysis

Putative proteins were called on dereplicated MAGs for each sample using Prodigal74 (-p single) and annotated against dbCAN275 and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database76 using DIAMOND v2.0.1577 (parameter: blastp, -e 1e−5, -k 1). Putative proteins of MAGs were further annotated using KofamScan v1.3.080 (parameter: -E 1e−5), METABOLIC v4.081, and FeGenie82. The CoverM v0.6.1 was used in genome mode (parameters: -min-read-percent-identity 0.95 -min-read-aligned-percent 0.75 -trim-min 0.10 -trim-max 0.90; https://github.com/wwood/CoverM) to calculate the relative abundance of MAGs in each sample. The bacterial MAGs with completeness ≥ 70% and contamination ≤ 10% and containing at least one ring cleavage gene were used for downstream analysis.

MAG-based predicted growth rate analysis

Bowtie2 v2.4.583 was used to build a Bowtie2 index of each MAG and output a set of alignments in SAM format (bowtie2-build; bowtie2 -p -x -1 -2). The in situ predicted growth rates of MAGs in each sample was estimated using Growth Rate InDex (GRiD) (v1.3)84 in the single mode (parameter: grid single -r -e sam -g -o). GRiD was suitable for estimating the growth rate of MAGs with low coverage in samples85. The closer dnaA/ori and ter/dif ratios are to one, the more likely accurate GRiD scores are84. Thus, we discarded each GRiD score with dnaA/ori or ter/dif ratios lower than 0.5 to increase the accuracy of growth estimates.

Phylogenetic analysis

Phylogenetic analysis of MAGs was achieved by the concatenated alignments of bacterial 120 conserved single-copy marker genes and archaeal 53 conserved single-copy marker genes through the GTDB-Tk v2.1.037 (gtdbtk classify_wf). IQ-TREE 286 was further used for the construction of phylogenetic trees (parameters: -st AA -m MFP -B 1000 -alrt 1000). The phylogenetic trees were visualized and annotated in the iTol (https://itol.embl.de)87, and edited by Adobe Illustrator.

Comparative genomic functional analysis

To further assess and compare the functional potential of anaerobic LMDs’ mineralization in B26-1 order MAGs, we downloaded all the reference MAGs belonging to this archaeal lineage in the GTDB database (release 214). Finally, a total of 112 reference MAGs and 22 MAGs (completeness ≥ 50% and contamination ≤ 10%) from this study were selected for the comparative functional analyses and phylogenetic analyses, as the MAG-based method described above. The habitat source of each reference MAG in B26-1 order was collected by manually searching the corresponding MAG isolation sites on the NCBI website (Supplementary Data 5).

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed on R v4.0.5 and Python v3.8, including the related package. All of the statistical methods were described along with the result. Sample clustering was achieved by hcluster88, based on the abundance of each CAZyme family gene. The bar chart and the boxplot were visualized using ggplot289. T-test (heteroskedasticity, two-tailed test) and one-way ANOVA (Tukey’s multiple comparisons test) were performed in R v4.0.5. The Linear discriminant analysis Effect Size (LEfSe) was performed with an open platform (https://www.bioincloud.tech/standalone-task-ui/lefse).

Limitations

While metagenomic techniques offer profound insights into microbial communities, the majority of studies to date have primarily employed descriptive and explanatory approaches, addressing the fundamental question of “who is present?”90. Given the paucity of research on microbial stratification in mangrove sediments, we leveraged metagenomic methods to elucidate the depth-dependent heterogeneity of C-cycling microbial communities between surface and subsurface sediments. This investigation establishes a crucial foundation for understanding blue C formation and forecasting future shifts in coastal blue C dynamics. Notwithstanding these advancements, challenges remain in extrapolating findings from laboratory settings to field conditions91. The microbial ecosystem is an intricate network characterized by dynamic spatio-temporal interactions among microbes and between microbes and their surrounding environment92,93. Additionally, in situ O2 concentrations, the real C use efficiency (CUE), the roles of microbes in lignin degradation, the activity of lignin-degrading enzymes, and their feedback mechanisms in response to environmental changes are not fully understood in mangrove sediment cores. To gain a more comprehensive understanding of microbial contributions to blue C conversion, it is essential to integrate additional research methodologies in future studies, such as in situ measurements, isotope tracing, and metatranscriptomics, to validate laboratory findings.

Responses