Design of functional and stable adhesion systems using reversible and movable crosslinked materials

Introduction

Adhesives are some of the most widely used tools to bond two similar or dissimilar objects together and have long been studied in chemical research. To date, various polymetric adhesives have been invented and commercialized, such as cyanoacrylate adhesives [1,2,3,4,5], silicone adhesives [6, 7], polyvinyl acetate adhesives [8, 9], acrylic adhesives [10], and epoxy adhesives [11, 12]. These conventional adhesives have been proven to exhibit good adhesion strength; however, their stability and recyclability are still challenging. It is evident from the recent global warming phenomenon that the environmental pollution caused by adhesive waste continues to be a problem for society. In response to the demand for a sustainable society, adhesives research is shifting toward long-lasting and functional adhesive systems. One promising approach involves tailoring the primary structure of adhesive polymers. For example, block copolymer-based adhesives have emerged as a powerful strategy [13], enabling the introduction of functional groups for improved strength [14,15,16], unique functionalities [17,18,19], and degradability [20, 21]. The microphase-separated structures of these materials further enhance adhesive performance [22]. Similarly, liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs), known primarily as actuators [23,24,25,26], are now being explored for their photoresponsive [27,28,29] and dynamic adhesion [30,31,32,33,34,35,36] properties. Another approach focuses on integrating secondary structures into adhesives. Natural polymers such as cellulose have been incorporated into adhesive systems [37, 38], achieving high performance [39,40,41,42,43] and reusability [44, 45]. Furthermore, interpenetrating polymer networks (IPNs) and semi-IPNs have proven particularly effective in bioadhesion [46,47,48,49], offering enhanced mechanical properties [50,51,52,53] and versatile functionalities [54,55,56,57] through secondary network integration.

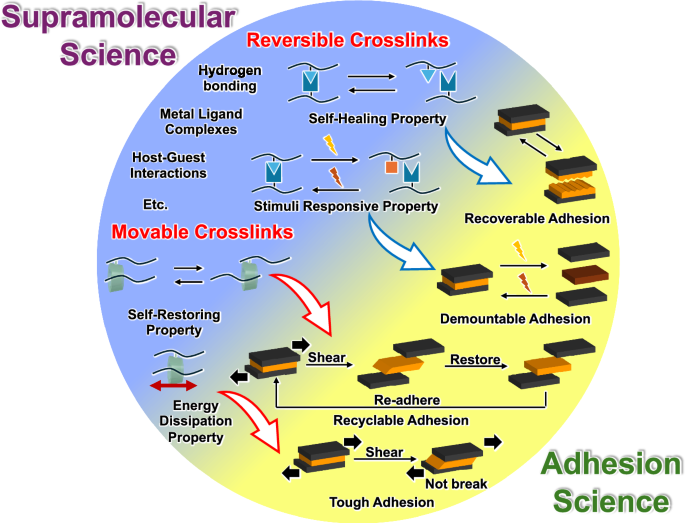

Recently, adhesion researchers have turned their attention to supramolecular science [58,59,60,61]. Supramolecular materials are expected to meet the recent demand for waste reduction, such as self-healing, stimuli responsive, self-restoring, and energy dissipation properties. To propose an adhesion system, a new strategy is to incorporate supramolecular science techniques in adhesion research to achieve recoverable, demountable, recyclable, and tough adhesives (Fig. 1).

Schematics of the design concepts of functional and stable adhesion systems using reversible and movable crosslinked materials

In this review, examples of research studies based on the design of reversible or movable crosslinks in supramolecular materials are presented. Then, new functional polymer adhesion methods that combine supramolecular science and adhesion science are discussed.

Materials with reversible crosslinks

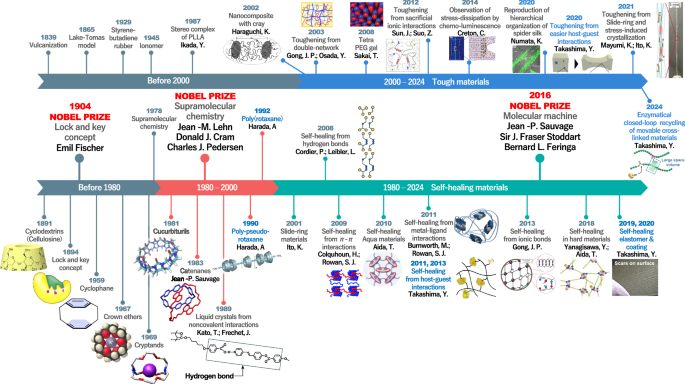

Figure 2 shows the timeline of supramolecular chemistry and material development [62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84]. The design of materials incorporating these supramolecular structures is effective for enhancing and controlling mechanical and functional properties [85,86,87].

Timeline of supramolecular chemistry and materials development

Materials with reversible crosslinks are widely used to achieve self-healing properties. Some self-healing materials utilize noncovalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonding [82, 88,89,90,91,92,93], metal-ligand complexes [79, 94,95,96], host‒guest complexes [80, 83, 97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106], ionic bonding [78, 81, 107,108,109], and π‒π interactions [77, 110]. Other materials utilize dynamic covalent bonding, such as Diels-Alder reactions [111], olefin metathesis reactions [112], imine bonds [113], and disulfide bonds [114]. Reversible crosslinks can be reformed spontaneously or in response to stimuli such as heat, humidity, or pH to repair physical damage and restore function.

The following sections describe the material design and evaluation of materials with typical types of reversible crosslinks.

Hydrogen bonding and metal-ligand complexes

Hydrogen bonding is one of the most well-known noncovalent interactions that has been long recognized for its importance in a wide range of materials and applications. In 1989, the supramolecular materials based on hydrogen bonds were reported by Kato and Frechet [88]. In 1997, Meijer and colleagues synthesized a trifurcated polymer end-modified with 2-ureido-4-pyrimidone, which forms dimers through the robust interaction of four complementary hydrogen bonds, resulting in a high association constant (Ka > 106 M−1) (Table 1) [92]. These dimers, formed at the termini of each polymer chain, self-assemble into a polymeric network thermodynamically. Such thermoplastic behavior shows potential for use in heat-melting adhesives. Later, in 2008, Leibler et al. introduced supramolecular materials based on hydrogen bonding derived from fatty acids and urea [93]. By condensing bifunctional and trifunctional fatty acids with diethylenetriamine and subsequently reacting them with urea, they generated oligomers capable of hydrogen bonding. When dodecane was incorporated as a plasticizer, the resulting materials exhibited rubber-like elasticity and self-healing at ambient temperature. To date, the majority of reported self-healing materials have been soft and elastic. However, in 2018, Aida and colleagues developed a hard self-healing material comprised by thiourea and ethylene glycol [82]. By utilizing relatively low-molecular-weight polymers, they achieved enhanced segmental mobility along with disordered hydrogen bonding. This combination enabled the material to exhibit both self-healing capabilities and a high Young’s modulus (>1 GPa), which was achieved through the effective exchange of numerous hydrogen bonds.

Another noncovalent interaction is metal coordination bonding. The high degree of tunability is a notable characteristic of metal coordination bonding that the stem from the wide variety of possible combinations of metal species and ligands. These bonds can be tailored across a wide spectrum of binding energies, ranging from approximately 100 kJ/mol to approximately 300 kJ/mol. Lehn et al. reported supramolecular polymers based on Zn²⁺ or Ni²⁺ coordination with telechelic polydimethylsiloxanes functionalized with acyl hydrazone-pyridine or acyl hydrazone-quinoline groups [94]. When these two different supramolecular polymer films were stacked and heated at 50 °C for 24 hours, random copolymer films were formed via metal-ligand exchange.

Promotion of self-healing by external stimuli

The conditions required for self-healing—such as time and temperature—are governed by the dissociation and reassociation dynamics of the metal-ligand complexes. To facilitate rapid self-healing under mild conditions, researchers have investigated the promotion of bond exchange via external stimuli. Rowan et al. developed a supramolecular polymer with Zn²⁺ coordination to ethylene–butylene copolymer functionalized at both ends with 2,6-bis(1’-methylbenzimidazolyl)pyridine [79]. When irradiated with UV light, the metal coordination bonds produce heat through excitation, accelerating the bond association and dissociation processes and thus enhancing self-healing.

Control of viscoelastic properties

The viscoelastic behavior of these materials can be modulated by toggling the association and dissociation of the metal-ligand complexes, which facilitates self-healing. During dissociation, the fluidity of the material increases, allowing it to fill any gaps or damage, followed by reassociation to complete the repair. Waite et al. demonstrated a pH-responsive sol-gel transition material that exploits the pH-dependent changes in the coordination amount of catechol with Fe³⁺. The material, crosslinked by a combination of Fe³⁺ and terminal catechol-modified four-chain polyethylene glycol, behaves as a fluid under acidic conditions but forms a hydrogel at alkaline pH (pH > 8) [95].

Switching kinetics of metal cages

The exchange kinetics of metal-ligand complexes in metal-organic cage (MOC) structures are influenced by the material’s topology. Self-healing can thus be controlled by incorporating units that alter their binding angles in response to external stimuli. Johnson et al. reported an organogel in which the MOC structure of a small Pd₃L₆ ring was linked to polyethylene glycol [96]. The small Pd₃L₆ rings exhibited readhesion through fast ligand exchange. Upon UV irradiation, the MOC structures transformed from small Pd₃L₆ rings to Pd₂₄L₄₈ rhombicuboctahedra due to changes in the bond angles. These larger rhombicuboctahedral structures did not exhibit readhesion, as their ligand exchange kinetics were significantly slower. Upon subsequent irradiation with visible light, the structures reverted from Pd₂₄L₄₈ rhombicuboctahedra back to Pd₃L₆ rings, thereby enabling control over reattachment properties by modulating ligand exchange kinetics.

Host-guest interactions

The host-guest interaction refers to a specific type of supramolecular interaction in which a macrocyclic host molecule encapsulates a guest molecule of appropriate size and geometry, forming an inclusion complex. Macrocyclic compounds such as crown ethers, cucurbit[n]urils (CB[n]s) [115], calix[n]arenes [116], pillar[n]arenes [117], and cyclodextrins (CDs) [118] have been extensively utilized as host molecules. The stability of these inclusion complexes is governed by the association constants, which are influenced by the size, shape, and charge characteristics of the guest molecule. Material design leveraging molecular recognition is a key aspect of host-guest interactions. This molecular recognition facilitates macroscopic self-assembly and sol-gel transitions, providing inspiration for the development of self-healing materials based on host-guest chemistry. This section focuses on two different approaches to the design of self-healing materials via host-guest interactions.

Host and guest polymers

In this approach, host or guest molecules are covalently attached to polymer chains. By blending the resulting host polymers with guest polymers, inclusion complexes are formed between the host and guest residues along the polymer side chains. This leads to the creation of supramolecular materials with reversible crosslinks based on these inclusion complexes. By selecting guest molecules whose association constants change in response to external stimuli, it is possible to fabricate stimulus-responsive materials. For example, redox-responsive hydrogels were synthesized by combining β-cyclodextrin (βCD)-modified poly(acrylic acid) with ferrocene (Fc)-modified poly(acrylic acid) (Table 2) [98]. The high association constant between βCD and Fc (Ka = 1.1 × 103 M−1) facilitated the formation of inclusion complexes with reversible crosslinks. Upon cutting and rejoining, the hydrogel regained 84% of its original strength after 24 hours. Upon exposure to an oxidant (sodium hypochlorite), the hydrogel dissociated into a solution, as the oxidized form of Fc (Fc+) exhibited low affinity for βCD, leading to the breakdown of inclusion complexes. The addition of a reductant (glutathione) reduced Fc+ to Fc, reforming the inclusion complexes and restoring the hydrogel.

Unlike cyclodextrins, which are less favorable toward cationic guests, crown ethers can form inclusion complexes with cationic species. The unshared electron pairs on the oxygen atoms of crown ethers stabilize the cationic guests. pH-responsive organogels were prepared by mixing dibenzo[24]crown-8 (DB24C8)-modified poly(methyl methacrylate) with bisammonium crosslinkers [99]. These organogels exhibited reversible gel-sol and sol-gel transitions upon the addition of a base (triethylamine) and an acid (trifluoroacetic acid), as well as self-healing capabilities, with surface cracks vanishing within 4 minutes.

Pillar[n]arenes serve as host molecules for cationic or electron-deficient guest molecules. Redox-responsive organogels were prepared by mixing pillar[6]arene-modified poly(methyl acrylate) with Fc+-modified polystyrene [100]. These organogels displayed gel-sol and sol-gel transitions upon treatment with a reductant (hydrazine) and an oxidant {silver tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate}. As pillar[n]arenes are relatively recent macrocyclic molecules, reports on self-healing materials using them remain limited. However, their potential lies in exploiting unique properties such as self-assembly and planar chirality in host-guest systems.

In the preparation of supramolecular elastomers by drying solutions of host-guest polymers, both the chemical structure and processing techniques are crucial. Elastomers obtained by drying a solution of peracetylated βCD-modified poly(ethyl acrylate) and adamantane-modified poly(ethyl acrylate) following ball-milling treatment demonstrated higher toughness compared to the elastomers obtained by the traditional stirring and casting methods [83]. Scratches made with a hard brush on the surface of the elastomer disappeared upon heating. Ball-milling induced strong mechanical stress that disentangled the polymer chains, increasing their mobility. This enhanced mobility facilitated the reformation of inclusion complexes, improving their mechanical strength and self-healing properties.

Another family of macrocyclic molecules, CB[n]s, shows distinctive host-guest chemistry. While CB[5], CB[6], and CB[7] form inclusion complexes with single guest molecules, CB[8] can simultaneously encapsulate two guest molecules, forming 1:1:1 heteroternary complexes with different guest species. Supramolecular materials can be formed from native CB[8] without requiring complex modifications. For example, mixing CB[8] with viologen-modified poly(2-hydroxyethyl acrylate) and naphthalene-modified poly(N,N-dimethyl acrylamide) yielded supramolecular hydrogels with thermally reversible crosslinks [101]. These hydrogels exhibited gel-sol and sol-gel transitions upon heating and cooling. CB[n]s can also form homogeneous 1:2 complexes with two identical guest molecules. Following the formation of a 1:2 inclusion complex between CB[8] and guest monomers, copolymerization with acrylamide produced supramolecular networks [102]. These hydrogels exhibited high fracture strains (over 10,000%) and demonstrated complete self-healing at room temperature.

Copolymers of host and guest monomers

Efficient formation of inclusion complexes between host and guest units within the material is essential for achieving effective self-healing. A simple mixing of host polymers with guest polymers is often suboptimal because the formation of inclusion complexes may be incomplete. As inclusion complexes form, the viscosity of the system increases, leading to reduced molecular mobility before all the host and guest moieties can interact. To address this issue, an alternative method involving the polymerization of the inclusion complexes between the host and guest monomers has been developed. This approach allows insoluble guest monomers to be solubilized through complexation with host monomers, resulting in a polymer chain that incorporates both host and guest units.

For example, copolymerization between the inclusion complex of βCD monomers and adamantane monomers with acrylamide produced supramolecular hydrogels (Table 3) [80, 103]. The resulting hydrogel was cut into two pieces and rejoined, and after 24 hours, the contact surface disappeared, with the hydrogel recovering 99% of its initial mechanical strength. Polymerization of inclusion complexes significantly improves healing efficiency significantly, even though supramolecular materials with poly(acrylamide) main chains do not exhibit self-healing properties under dry conditions and require humid conditions to function effectively.

To overcome this problem, poly(methoxy triethylene glycol acrylate) (polyTEGA) was employed as the main chain polymer. With a lower glass transition temperature (Tg of polyTEGA = -50 °C compared to the Tg of polyacrylamide = 165 °C), the self-healing xerogels formed using polyTEGA demonstrated notable self-healing properties [105]. These xerogels regained 60% of their initial strength at 100 °C after standing for 24 hours. Furthermore, a high association constant between the guest unit and βCD contributed to improved healing performance.

In addition to mechanical healing, it is possible to develop materials that change color in response to stimuli by using guest molecules with different absorption spectra in the free and inclusion-complex states. For example, phenolphthalein appears purple in basic aqueous solutions and becomes colorless upon complexation with βCD. Stimulus-responsive hydrogels were created using inclusion complexes between βCD and phenolphthalein as the crosslinks [104]. These hydrogels remained colorless in basic KH₂PO₄/NaOH buffer (pH = 8), but upon heating to 87 °C, the inclusion complex dissociated, turning the gel purple. Upon cooling, the gel returned to its colorless state as the inclusion complex reformed. This hydrogel also exhibited color changes when exposed to competing guest molecules or electrical currents (Joule heating). Additionally, self-healing xerogels were produced by removing the solvent.

Bulk polymerization without solvents is another approach for the preparation of dry self-healing materials. In this method, the inclusion complex between the host and guest monomers must dissolve in the liquid main chain monomer. However, conventional CD monomers with numerous hydroxyl groups are insoluble in most hydrophobic main chain monomers [106]. To address this issue, hydrophobic CD monomers with fully acetylated hydroxyl groups were used to fabricate self-healing elastomers. The bulk copolymerization of peracetylated CD monomers with 2-ethyladamantyl acrylate and ethyl acrylate was carried out, resulting in an elastomer that, when cut into two pieces and rejoined, recovered 95% of its initial strength within 4 hours at 80 °C. Additionally, this elastomer can be recycled. The toluene-swollen sample was ground using a ball mill to form a slurry, and upon removing the toluene, a recycled sample with the same properties as the original sample was obtained.

Materials with movable crosslinks

Movable crosslinks consist of a mechanically interlocked architecture where polymer chains thread through macrocyclic molecules, forming a dynamic and flexible network. These movable crosslinked materials exhibit enhanced toughness, as stress is efficiently dispersed through the sliding motion of macrocyclic molecules along the polymer chains. This sliding motion allows the material to distribute mechanical stress more evenly, preventing localized failure. Additionally, self-restoring properties are anticipated due to the entropic elasticity of the system, which enables the movable crosslinks to return to their original positions once the stress is removed.

This section highlights typical approaches for the fabrication of movable crosslinked materials. By integrating macrocyclic compounds such as cyclodextrins, crown ethers, or cucurbiturils, the polymer network can achieve both flexibility and resilience. The dynamic nature of these movable crosslinks is crucial for applications that require materials with superior mechanical performance and self-restoring capability.

Polyrotaxane as a starting material

Polyrotaxane is a macromolecular structure in which macrocyclic molecules are threaded onto a linear polymer (referred to as the “axle”), with bulky stoppers at both ends to prevent the macrocycles from detaching [75, 119,120,121,122,123]. In 1990, α-cyclodextrins (αCDs) were first threaded onto polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains, forming poly-pseudorotaxanes. Later, in 1992, a full polyrotaxane was synthesized through an end-capping reaction of αCD-PEG bisamine complexes using 2,4-dinitrofluorobenzene. Previous reports have shown that rotaxane structures can strongly enhance the toughness of materials [124, 125].

Movable crosslinked materials can be created by using polyrotaxanes as crosslinkers. Ito et al. introduced a “topological gel” by crosslinking two αCDs in different polyrotaxanes via cyanuric chloride [76, 125] (Table 4). In contrast to the conventional covalent crosslinks that concentrate stress in localized areas, these movable crosslinks act as pulleys, distributing tension evenly along the polymer chains. This stress dispersion, often referred to as the “pulley effect,” prevents polymer chain rupture, enhancing the toughness of the material. The pulley effect has been applied in industry to scratch-healing coatings, where movable crosslinks inhibit crack formation, allowing the coating to revert to its original state due to its elasticity. Movable crosslinked materials utilizing polyrotaxanes of pillar[5]arene were also developed by Ogoshi et al. [126].

The sliding motion of polyrotaxane-based movable crosslinks further promotes the reformation of reversible crosslinks, improving self-healing properties. For example, self-healing materials were prepared by copolymerizing acrylamide with 4-vinylphenylboronic acid in the presence of polyrotaxane with hydroxypropyl-modified αCDs [127] (Table 5). The resulting hydrogel contained dynamic covalent bonds between boronic acid and the diol groups of the αCDs in the polyrotaxane. These hydrogels exhibited a significantly higher healing efficiency (~100% within 15 minutes) than the reference hydrogels with dynamic covalent bonds involving linear polysaccharides (~20% in 60 minutes). The superior healing was attributed to the enhanced mobility provided by the movable crosslinks. Additionally, self-healing hydrogels based on αCD in polyrotaxane crosslinked by inclusion complexes between βCD and adamantane have also been reported [128]. This approach leverages the reversible and dynamic nature of host-guest interactions to further enhance the self-healing of materials.

Formation of rotaxane/polyrotaxane structures in the main chain

The formation of rotaxane or polyrotaxane structures on the main polymer chain can be divided into two main methods:

Polycondensation after the formation of the pseudorotaxane/rotaxane structure

In this approach, the pseudorotaxane or rotaxane structure is formed first, followed by polycondensation. For example, photoresponsive movable crosslinked materials were fabricated using a pseudo[2]rotaxane consisting of lysine-modified αCD and diamine-modified azobenzene (Azo) [129] (Table 6). Polycondensation with succinimidyl-modified PEG produced hydrogels with movable crosslinks. Azobenzene showed photoinduced isomerization between its trans and cis forms. The trans form exhibited high affinity for αCD, while the cis form showed low affinity for αCD. When exposed to UV light (wavelength: 365 nm), isomerization from trans-Azo to cis-Azo led to the unthreading of αCD from the axle, causing the xerogels to bend toward the light source as the CD units slid along the PEG chain. The self-restoration capabilities of movable crosslinked materials can be enhanced by incorporating high-affinity guest molecules into the axle of the [2]rotaxane. Yan et al. designed materials with [2]rotaxane structures using a dibenzo-24-crown-8 ring and a dibenzylammonium salt as the axle [130]. The ring and axle were functionalized with vinyl groups, and a thiol-ene click reaction with 3,6-dioxa-1,8-octanediol was carried out to create the movable crosslinked materials. The macrocyclic rings favored the cationic guest units, leading to dissociation when mechanical stress was applied. This dissociation dissipated stress, resulting in a tougher material. After the stress was removed, host-guest interactions facilitated the reassociation of the macrocycles, allowing rapid recovery of the original shape of the material.

Copolymerization between macrocyclic monomers and main chain monomers

The second method involves the formation of movable crosslinks by copolymerizing macrocyclic monomers and main chain monomers. For example, movable crosslinked elastomers were created by bulk copolymerization of hydrophobic CD monomers with alkyl acrylates [131]. The formation of movable crosslinks depended on the cavity size of the CD and the size of the main chain monomer. When ethyl acrylate (EA) and peracetylated γCD monomers were copolymerized, the poly(EA) chains threaded through the γCD cavities, resulting in movable crosslinks. By contrast, the copolymerization of butyl acrylate with peracetylated βCD monomers resulted in fewer movable crosslinks, demonstrating the importance of the macrocyclic cavity size and the main chain monomer in achieving effective crosslinking. The resulting elastomer exhibited higher toughness compared to poly(EA) with conventional covalent crosslinks. Hydrophilic movable crosslinked materials were also prepared by the copolymerization of CD monomers with liquid acrylamide monomers such as N,N-dimethyl acrylamide (DMAAm), 4-acryloylmorpholine, and N,N-dimethylaminopropyl acrylamide [132]. While conventional methods of mixing CDs with poly(alkyl acrylate) or poly(acrylamide) derivatives in water do not yield polyrotaxane/poly-pseudorotaxane structures, these copolymerization methods enable the preparation of such structures that cannot be achieved through traditional techniques. Using similar methods, movable crosslinked materials with hydrophilic main chains and hydrophobic movable crosslinks were also prepared. The -OH groups on the CDs were converted to -OAc groups. The lack of hydrogen bonding between the CD units and the polymer main chains enhances the mobility of the movable crosslinks. Under appropriate water content, the materials exhibited enhanced toughness due to multiple relaxations of movable cross-links and reversible hydrophobic interactions [133].

Supramolecular adhesion systems

In this section, the authors introduce supramolecular adhesion systems using reversible and movable crosslinked materials. Adhesion systems have two key components: adhesives and adherends (substrates). Achieving optimal performance requires a balanced focus on two critical factors: the interaction between the adhesive and the adherends and the cohesive interactions within the adhesive itself. These combined interactions are vital for ensuring strong and reliable adhesion systems. Here, we focus on the adhesion systems on the surfaces of hard substrates, including polymer (PMMA, nylon, etc.), inorganic (glass, silicon wafers, etc.), and metal (stainless steel, copper, etc.) substrates.

Adhesion systems using reversible crosslinked materials

In the previous section, the authors discussed reversible crosslinked materials, which exhibit self-healing properties, robust mechanical performance, and multifunctional capabilities. Owing to the reversibility of the crosslinks, a variety of adhesives have been developed on the basis of mechanisms such as hydrogen bonding [134,135,136,137,138], metal-ligand complexes [139,140,141,142,143,144,145], and host-guest interactions [146].

Two primary strategies can be exploited to construct adhesion systems using reversible crosslinked materials. The first strategy involves the introduction of these crosslinks between the adherends (substrates) and the adhesives, while the second strategy involves the use of the reversible crosslinked materials directly as adhesives. The former strategy emphasizes maximizing the adhesion at the interface between the adhesives and the surfaces, whereas the latter focuses on enhancing the cohesion within the adhesive itself. Both approaches aim to achieve recoverable and stimuli-responsive adhesion, allowing the material to be rejoined or manipulated under specific conditions.

In this section, the authors outline the design principles, preparation methods, evaluation techniques, and outcomes for adhesion systems using reversible crosslinks. These systems offer significant potential for applications requiring durable yet adaptable bonding solutions.

Hydrogen bonding

Hydrogen bonding interactions are often used for microscale adhesion. However, it is challenging to achieve adhesion at the macroscale with single hydrogen bonds because of the weak binding energy. Multiple hydrogen bonding (MHB) refers to the simultaneous formation of several hydrogen bonds between two or more molecules, leading to highly specific and robust molecular interactions. The cumulative effect of MHB interactions results in increased binding strength and enhanced stability of the molecular assembly. Several studies on macroscale adhesion through MHB have been reported in the literature. Long et al. introduced nucleobase-containing units (adenine and thymine) into acylate-based adhesives (Table 7) [136]. When adenine- and thymine-functionalized copolymers were blended, they formed a thermodynamically stable complex through complementary adenine-thymine hydrogen bonding. This base pairing effectively acted as a physical cross-linking mechanism, influencing the self-assembly of the polymeric network. The resulting nucleobase-functionalized polyacrylates displayed tunable adhesion (20 N/in) and cohesion (80 N/in2). Zimmerman et al. successfully achieved macroscopic adhesion between polystyrene films and glass surfaces modified with 2,7-diamidonaphthyridine (DAN) and ureido-7-deazaguanine (DeUG) units [137]. Through the introduction of high-affinity DNA base analogs, the adhesion systems exhibited repeatable adhesion properties at the macroscale under ambient conditions. The recycling adhesion property was also confirmed. The adhesion status was maintained after three cycles. Another approach involves the functionalization of a rubbery copolymer containing thiolactone derivatives with side-chain barbiturate (Ba) and Hamilton wedge (HW) groups. The heterocomplementary interactions between Ba and HW form hydrogen-bonded supramolecular polymeric networks, significantly enhancing the integrity of the polymeric network. These interactions, coupled with the individual Ba or HW moieties, enable strong adhesion to diverse substrates, surpassing the performance of commercial glues and other adhesives.

Metal ligand complexes

According to the previous section, materials containing metal-ligand complexes exhibit tunable mechanical properties, stimuli-responsive properties, and self-healing properties. Moreover, due to the nature of metal coordination bonding, adhesion systems containing metal-ligand complexes are expected to achieve high adhesion on the surface of metal substrates. For example, Sun et al. reported a biobased supramolecular adhesive (BSA) using castor oil, melevodopa, and iron ions as building blocks (Table 8) [139]. Adhesion is reinforced through noncovalent interactions between the catechol units of melevodopa and adherends, while cohesion is enhanced by metal-ligand coordination between catechol and Fe³⁺ ions. This combination of strong adhesion and tough cohesion resulted in an exceptional adhesion strength of 14.6 MPa at ambient temperature, achieving record performance among biobased and supramolecular adhesives. Remarkably, the BSA also exhibited debond-on-demand properties under heat and near-infrared light stimuli. Additionally, the adhesive shows excellent reusability, retaining over 87% of its original strength after ten cycles of reuse. Another example of stimuli-responsive and reversible adhesion involves 2,6-bis(1’-methylbenzimidazolyl)-pyridine (Mebip) ligands (Mebip-PEB-Mebip), which can coordinate to metal ions [Zn(NTf2)2] and form a metallosupramolecular polymer [142]. The adhesives exhibited shear strengths of 1.8−2.5 MPa and could debond quickly under load when exposed to light or heat. The adhesive strength was fully restored after readhesion under the same conditions. Furthermore, metal ligand complexes can also be used as adhesion promoters. Wong et al. incorporated first-row transition metal β-diketonates, specifically Co(II) and Ni(II) hexafluoroacetylacetonate, into epoxy/anhydride resins, resulting in significant improvements in lap shear strength (over 30% before moisture aging and 50% after moisture aging) [143]. These insights provide a promising avenue for future research into functional additives aimed at the optimization of curing kinetics and enhancement of epoxy-copper joint robustness through polar group coordination strategies.

Host-guest interactions

There are two main methods to introduce host-guest interactions into adhesion systems with hard substrates:

Modified substrates with host and guest molecules

In this approach, guest molecules are decorated on the substrates in advance (guest substrates) and then attached to the host polymers or host-modified substrates (host substrates) to achieve adhesion through molecular recognition. For example, Ravoo et al. prepared azobenzene polymer brushes (PAZA-PHEA) on glass surface through surface-initiated atom transfer radical polymerization (Table 9) [147]. It was demonstrated that two surfaces coated with azobenzene brushes can be effectively glued together using a βCD polymer. This adhesive system displayed remarkable strength and could support a load of up to 700 ± 150 g/cm². They also reported supramolecular adhesion systems between two hard substrates (glass and silicon wafers) functionalized with either βCD or arylazopyrazole polymer brushes (Table 10) [148]. The adhesion performance of these systems was evaluated both in air and underwater and under UV irradiation. All the systems exhibited strong and reversible adhesion in air due to the multivalent host-guest interactions. Our group previously reported selective adhesion systems that focus on the interaction between CD-host gels and guest molecule-modified glass substrates (guest Sub) [149]. For Azo and αCD gels, adhesion is regulated through photoisomerization. When Azo molecules on a substrate (Azo Sub) are irradiated with UV light (360 nm), they switch from their trans to cis configuration, reducing their affinity for αCD and causing the gel to detach. Conversely, visible light (430 nm) restores the trans configuration, reinstating the gel’s adhesion. Similarly, redox stimuli can control adhesion between ferrocene (Fc)-modified substrates and βCD gels. When an oxidant such as FeCl₃ is applied, ferrocene is oxidized to a monovalent cation, weakening the interaction and causing the gel to detach. A reducing agent such as GSH can reverse this oxidation, restoring gel adhesion. Moreover, the adhesion of dissimilar substrates was explored based on host-guest interactions [150]. By using carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP) as an Ad-modified substrate, aluminum (Al) substrates modified with βCD were found to adhere to the Ad-CFRP Sub with a strength of 1.98 MPa. After the bonded substrates were fractured, water (15 µL) was applied to the fractured surface, followed by reclipping and drying, restoring adhesion with the original rupture strength.

Adhesives with host-guest complexes

In this approach, materials containing host and guest polymers are first prepared and attached between two substrates, which is similar to conventional adhesives. For example, Scherman et al. reported CB[8]-based supramolecular hydrogel networks as dynamic adhesives [151]. These hydrogels demonstrate strong adhesion properties across a wide range of substrates (such as glass, stainless steel, aluminum, copper, and titanium) without requiring any surface pretreatment or curing agents. By curing the hydrogel around the softening temperature, a tough and healable adhesive interlayer is formed, offering flexibility in its application.

Adhesion systems using movable crosslinked materials

Materials with movable crosslinks, such as reversible crosslinked materials, have great potential for use in adhesion systems. These systems offer enhanced flexibility and adaptability due to movable crosslinks that can move under stress, leading to improved adhesion and cohesion properties. Two main strategies are employed to design adhesion systems using movable crosslinked materials. The first strategy is the direct use of movable crosslinked materials as adhesives. This approach leverages the high toughness and dynamic nature of movable crosslinked materials to ensure strong adhesion strength and excellent reusability. These materials can accommodate stress and recover their properties, making them suitable for applications requiring durability and reusability. The second strategy involves the formation of movable crosslinks between adherends via in-situ polymerization. In this method, movable crosslinks are created directly between the adherends, resulting in a unique topological structure. This strategy prioritizes achieving high cohesion strength by utilizing the dynamic yet robust nature of the crosslinked network. Several recent studies have explored the integration of rotaxane structures into adhesive formulations, demonstrating improved mechanical performance and adhesion strength [152,153,154,155,156,157,158,159,160].

In this section, the authors focus on the design, preparation, and evaluation of adhesion systems utilizing movable crosslinks. The results of these studies highlight the promising role of movable crosslinks in the development of advanced adhesives with enhanced durability, flexibility, and reusability.

Due to their high toughness and self-restoring behavior, movable crosslinked materials have been successfully employed in the development of pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSAs). PSA is a self-standing film and is widely used in industrial applications where low residue and repeated peeling are required. Kim et al. demonstrated that triacetyl βCD functionalized with 2-isocyanatoethyl acrylate (βCD−AOI) formed a threaded compound with poly(butyl acrylate) (pBA), creating a supramolecular sliding effect within the polymer matrix (Table 10) [158]. Elastomers and pressure-sensitive adhesives (PSAs) incorporating supramolecular cross-linkers exhibit remarkable stretching and adhesion properties, which are difficult to achieve with conventional cross-linkers. Our group also reported tough, recyclable PSAs by preparing self-standing films using movable crosslinks [159]. Films were formed by bulk polymerization of M-PEA-CD (0.5) copolymerized with a mixture of 99.5 mol% EA and 0.5 mol% mono-6O-acrylamidomethyl-icosaacetyl-βCD (TAcβCDAAmMe) between two detachable films. M-PEA-CD (0.5) exhibited excellent adhesive properties, showing flexibility that allows interfacial adhesion and improved mechanical properties that contribute to cohesion. While M-PEA-CD (0.5) also showed viscoelastic behavior, suggesting cross-link formation, it became a homogeneous solution when immersed in ethyl acetate which is a good solvent. At this polymerization ratio, M-PEA-CD (0.5) could be recycled at least 10 times by dissolution and reapplication/drying without a loss of adhesive properties.

On the other hand, our group achieved adhesion systems between nylon substrates through the introduction of the single-movable cross-network (SC) materials described above [160]. The SC adhesion material [SC(DMAAm) Adh] was prepared via bulk polymerization of DMAAm monomer solutions containing photoinitiators and polymerizable acetylated γCD (TAcγCDAAmMe) between nylon substrates with silane anchors modified on the surface. In addition, adhesion systems with chemical crosslinks [CP(DMAAm) Adh] and without crosslinks [P(DMAAm) Adh] were prepared for comparison. SC(DMAAm) Adh showed high durability against deformation and stress application under various conditions, particularly when the moisture content was approximately 20%. SC(DMAAm) Adh exhibited high values for both shear stress and shear strain, with a toughness that was 1.3 ~ 1.6 times higher than those of CP(DMAAm) Adh and P(DMAAm) Adh. Furthermore, SC(DMAAm) Adh exhibited excellent stress dissipation, self-restoring behavior, and creep resistance. The movable crosslink has an interlocking structure and thus its cohesion energy is equivalent to that of a covalent bond while still exhibiting stress dissipation. This enabled enhanced durability under various conditions.

Conclusion

This review summarizes various works on supramolecular materials with reversible and movable crosslinks and their application as adhesives. By incorporating reversible or movable crosslinks into polymer networks on the basis of supramolecular science, various polymer adhesive materials have been shown to achieve unprecedented mechanical and functional properties. These designs are expected to be developed as adhesive materials with novel functions.

In recent years, global challenges such as environmental sustainability and the realization of a circular economy have also become relevant to adhesive materials. It is necessary to develop new adhesion systems that not only enable the recycling of the adhesive itself but also allow the substrates to adhere. While maintaining stability and stress relaxation, the introduction of supramolecular science techniques offers a new paradigm for adhesive technologies. Adhesion based on selective and specific molecular recognition is closely related to the formation of complexes that respond to external stimuli, which is the forte of supramolecular science.

Moving forward, we anticipate that the fusion of these adhesive and supramolecular science technologies will lead to the creation of new high-performance adhesive materials and contribute to the reuse of resources in the circular society.

Responses