Determination of health status during aging using bending and pumping rates at various survival rates in Caenorhabditis elegans

Introduction

Aging is an inevitable time-dependent process involving degenerative physiological alterations in tissues and organs that increase the susceptibility to chronic diseases and eventually lead to death. Thus, slowing down aging would significantly affect overall health1. However, it is apparent that prolonged longevity does not necessarily correlate with a corresponding extension in an individual’s health; a longer lifespan not accompanied by health translates to prolonged fragility. Therefore, alongside recognizing the importance of extending lifespan, an emerging focus has appeared on improving health in longevity, defined as ‘healthspan,’ time free of age-related health issues2,3,4. Extending the ‘healthspan’ implies significant improvement in the quality of life by reducing ‘gerospan,’ the duration of fragility and morbidity at the end of the lifespan3. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), healthy aging is a concept of focusing on maintaining functional abilities during the later stage of life when functional abilities gradually decline to the point that an individual loses the ability to meet the basic needs of being mobile, making decisions, continue social interactions, and contribute to society5. Thus, along with prolonging the lifespan, extending the healthspan would significantly improve the quality of longevity.

Understanding human aging is essential, but there are significant challenges to investigating aging due to the length of time needed, i.e., even two commonly used small short-lived vertebrates like mice and zebrafish have a lifespan of approximately three years. For this reason, much age-related research uses two invertebrate models, namely, Caenorhabditis elegans (nematode) and Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly). Knowledge from these invertebrate models has significantly contributed to our current understanding of genetics and the development of potential intervention strategies to mitigate aging6. C. elegansis often selected as a model system for studying aging7,8,9,10, and is an eukaryotic, multi-organ nematode with a lifespan of around 3–4 weeks at 20 °C. It can be easily maintained in laboratory conditions with the non-pathogenic bacteria Escherichia coli OP50 as a food source. Having 65% homology with human disease-related genes, C. elegansis used in many life science research areas and is particularly useful for studying aging7,11,12,13,14.

Among several metrics used to determine healthspan, physical ability is one of the primary metrics used to indicate the quality of healthy aging15. This was applied to develop the ‘Frailty Index’ based on various markers of muscle function in humans and mice16,17. Like humans and other animals, C. elegans express behavioral decline over the lifespan, including deterioration of muscle functions3,4,18. A number of studies have determined the healthspan in C. elegans19,20,21,22,23 by measuring a locomotive activity or pharyngeal pumping rate, which are well known to decline with aging in C. elegans11,12,21,23,24. However, the definitions of ‘healthspan’ in these publications were inconsistent: 50% of maximum response20,23or arbitrary cut-offs21,23. One report by Rollins et al.19 developed a model system to determine the period of healthspan; however, the authors used separate calculations from individual markers, leading to multiple estimations of healthspan in a single experimental setting. Another study by Huang et al.25suggested four aging stages; 1] progeny reproduction stage, 2] vigorous motor activity stage, 3] reduced motor activity stage, and 4] minimal motor activity stage. However, this study again did not define the exact cutoff for each stage and whether each stage is considered a part of the healthspan or gerospan25. In addition, studies have used an inconsistent selection of healthspan markers18,25,26,27. These suggest a significant knowledge gap in determining healthspan, even in an experimental model system, such as C. elegans28,29,30. Thus, we measured the various health markers of C. elegans and chose the most representative marker(s) that can be used to develop a biometric index that can provide a comparable determination of healthy aging between research groups.

Results

Lifespan determination with wild-type C. elegans

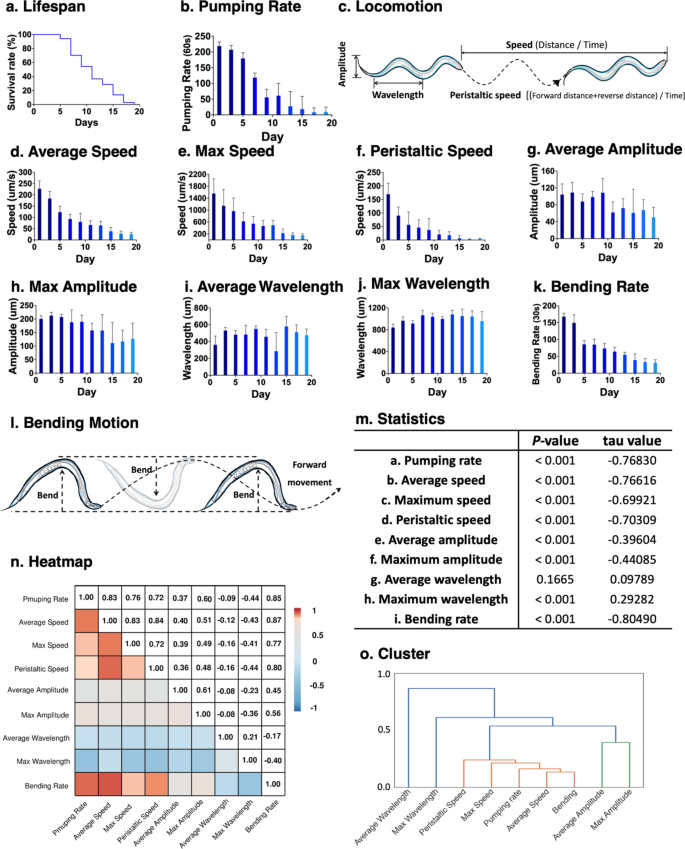

Lifespan is the most critical metric of aging studies5,31,32. Thus, we first measured the lifespan of wild-type C. elegans (Fig. 1a). In this condition, the median lifespan was 11 days, and the maximum lifespan was 19 days (Fig. 1a).

Lifespan and various health markers in C. elegans. Lifespan data and physical activity of C. elegans over age were quantified to identify the correlation between individual markers. (a) The wild-type C. elegans was used for lifespan assay and began measurement with first-day adult worms as day 0. Media was exchanged with fresh media with fresh E. coli OP50 every other day and incubated at 20˚C. Survival was recorded every other day until all worms died (n = 145). (b) The pharyngeal pumping rate was recorded every other day with 12 randomly selected worms. The pumping rate was counted under the microscope for 1 min. (c) Overview of physical activity-associated markers observed from C. elegans. (d–j) Markers related to locomotion were measured every other day to determine the muscle function using the wild-type C. elegans. Ten randomly selected worms were transferred to the plate and acclimated for 30 min before measurement. WormLab software was used to record a 1-minute recording (7.99 frames/second), and then analysis and calculation were performed. Peristaltic speed is defined as ‘(Length of forward motion + Length of reverse motion) / Total number of frames’ by the software manufacturer WormLab. (k) The bending rate was counted under the microscope for 30 seconds from 16 randomly selected worms. (l) Scheme of bending movement of C. elegans. (m) Pumping rate, speed, amplitude, wavelength, and bending rate were analyzed with Mann-Kendall test to determine the trend of each health metric over day. Average wavelength did not show significance, but maximum wavelength was significantly increased. All other healthspan markers were significantly decreased. (n) The correlation coefficient (r) was calculated and visualized in a heatmap. (o) Cluster analysis was performed to confirm correlation coefficient calculation and identify closely associated groups. Values represent means ± S.D. (n = 12 for b, n = 10 for d-j, and n = 16 for k).

Quantitative measurement of age-related markers

To determine the correlation among various health makers currently in use, we have measured various age-associated markers from the wild-type C. elegans (Fig. 1b-l). Among these, pharyngeal pumping rate (Fig. 1b), average speed (Fig. 1d), maximum speed (Fig. 1e), and bending rate (Fig. 1k) were previously used markers to determine the healthspan18,25,33,34,35. In addition to these, we also measured peristaltic speed (Fig. 1f), average amplitude (Fig. 1g), maximum amplitude (Fig. 1h), average wavelength (Fig. 1i), and maximum wavelength (Fig. 1j). All these markers, except pharyngeal pumping and bending rates, were collected using specialized software described in the method section.

The maximum pumping rate is observed during the young adult stage and then displays a gradual decline associated with aging20,23. The pumping rate of wild-type worms on the first day of adulthood (day 1) was 216 ± 4 per minute and decreased to 113 ± 4 per minute on day 7, a 52% decrease (Fig. 1b and m). Others consistently report these4,25.

Locomotive movement of C. elegans is a result of muscle contraction between dorsal and ventral muscles, generating contraction forces that enable the worm to move forward and backward (Fig. 1c)36,37, which declines with age38,39. Overall, all but the average wavelength showed a significant trend over time (Fig. 1m). Our result shows the highest locomotion speeds were observed during early adulthood and displayed a declining trend over time (Fig. 1d-f); worms significantly dropped average and maximum speeds on day 5 (Fig. 1d&e). Similarly, we observed a significant drop in peristaltic speed with age (Fig. 1f). Muscle contraction of C. elegans generates amplitude and wavelength36,39. While the average and maximum amplitudes significantly declined over time, the maximum wavelength showed a slight increase with age (Fig. 1g-j).

The bending rate is another type of movement generated by the muscle contraction of the dorsal and ventral muscles of C. elegans, which enables the worm to swim, forming a C-shape curve (Fig. 1l)36,37. Previous studies on healthy aging have mainly used pharyngeal pumping rate or locomotion markers based on the crawling movement of C. elegans18,25,35,38. However, recent studies have used the bending rate as an alternative health indicator26,27,29,40. This is also advantageous as no special software is needed to observe the bending rate. The bending rate of C. elegans decreased over time (Fig. 1k), similar to those of average and maximum speeds and pumping rates.

Correlation between health markers

The correlation coefficient (r) was calculated between health markers observed to determine the correlation between them, and the results are shown as the heatmap (Fig. 1n). As shown in Fig. 1b-l, markers with significant age-dependent decline resulted in higher |r| values (Fig. 1n): pumping rate, average and maximum speed, peristaltic speed, and bending rate. The highest |r| value of 0.87 was between the bending rate and average speed data, followed by 0.85 between the bending rate and pharyngeal pumping rate. The bending rate also showed a strong linear relationship with maximum and peristaltic speeds with |r| values of 0.77 and 0.80, respectively. However, data sets with less or no significant age-dependent trends – wavelength and amplitude- showed a weak correlation with other data sets, indicating that these markers are not good markers to be used for health status determination.

While bending rate and speed showed the highest correlation, pumping rate also showed a relatively high correlation with locomotion markers. The |r| values between pumping rate and average speed were 0.83. Although the pumping rate showed relatively lower |r| values with maximum speed (0.76) and peristaltic speed (0.72), these results suggest that the pumping rate highly correlates with bending rate and average speed. Thus, the pumping rate is also considered a good representative marker of health status.

Next, we performed clustering analysis to confirm the correlation coefficient result further and to group health markers. Results in Fig. 1o support that the bending rate and average speed were the first clusters, consistent with the correlation coefficient result in Fig. 1n. Other health markers, bending, average speed, pumping rate, maximum speed, and peristaltic speed, were clustered into the same group. However, wavelength and amplitude data have been separately clustered into different groups. This suggests bending, average speed, pumping rate, maximum speed, and peristaltic speed have a strong positive correlation, while wavelength and amplitude do not. Furthermore, we have used principal component analysis (PCA) to determine the correlation between health markers (Suppl. Fig. S1). The PCA result showed that 1 principal component is sufficient to account for the variance of health markers, which supports the previous correlation coefficient and clustering result.

Overall, our correlation coefficient |r| calculation and cluster analysis results indicate that among markers tested, the bending rate can be used to represent muscle-associated health markers of the worm. Alternatively, these results also suggest that the pumping rate can be used when no appropriate bending rate can be measured, such as certain defects of motor function due to gene mutation or certain experimental conditions41,42,43. Using either a bending or pumping rate to represent an individual’s health would be advantageous as measurements of both markers do not require special equipment or software, which will further allow for comparing interlaboratory results on aging.

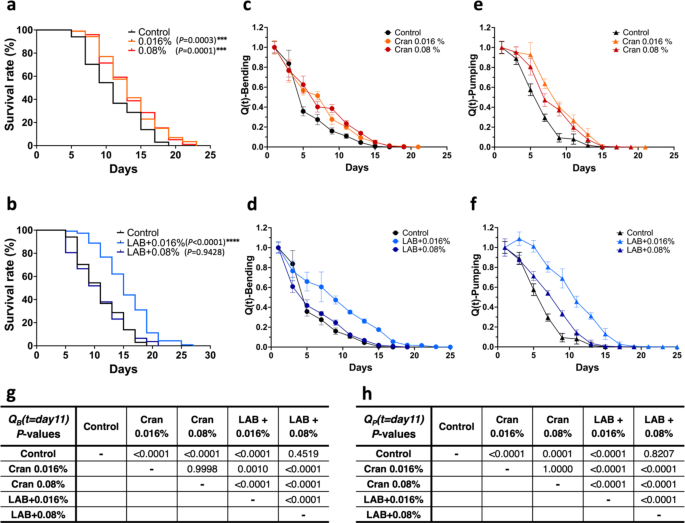

Lifespan and healthy aging measurements with various treatments

To determine the concept of healthy aging further, we measured the lifespans and health markers of wild-type C. elegans after treating them with different treatments (Fig. 2a&b, Suppl. Fig S2-S6). First, we tested cranberry juice concentrate, which has been reported to extend the lifespan and healthspan in C. elegans44. The concentrations of cranberry juice concentrate used were selected based on our previous publication at 0.016% and 0.08% to deliver health benefits without altering the pH of the culture medium used45,46. Treatments of cranberry juice concentrate significantly extended lifespan (P = 0.0003 for 0.016% and P = 0.0001 for 0.08% cranberry juice treatment over the control) (Fig. 2a); treatment of either 0.016% or 0.08% cranberry juice extended the median lifespan (13 days for both) compared to the control (11 days). In health markers, both cranberry juice treatments significantly delayed the decline of average and maximum speeds, pumping rate, and bending rate compared to the control group (Suppl. Fig. S3&S4).

Quality-adjusted value of various treatments in wild-type C. elegans. (a & b) Lifespan data of cranberry juice concentrate treatments (Cran) and (b) cranberry juice concentrate with Lactobacillus plantarum co-treatments (LAB). The survival measurement began with adult worms at day 0. Media was changed every other day with fresh media with either fresh E. coli OP50 or L. plantarum and incubated at 20˚C. Cranberry juice concentrate treatment (Cran) was either at 0.016% or 0.08%. Survival was recorded every other day until all worms died (A & B, n = 87–116). Lifespan data were analyzed using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests. Groups with *** and **** are significantly different compared to control group at P < 0.001 and P < 0.0001, respectively. Quality-adjusted values (c–f) were calculated using the equation of (:{Q}_{B}left(tright)=Srleft(tright)times:{B}^{*}left(tright):text{o}text{r}:{Q}_{P}left(tright)=Srleft(tright)times:{P}^{*}left(tright)). Sr, survival rate; t, time; B*, bending rate normalized to the maximum values of the group; P*, pumping rate normalized to the maximum values of the group. Values represent means ± S.D. (n = 16 for c & d and n = 12 for e & f). Note that Quality-adjusted values using bending rates (c and d) and pumping rates (e and f), respectively, (g and h) were analyzed with the parametric polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA models with group, polynomials (linear, quadratic and cubic effects) of day, and their interactions (between group and polynomial effects of days). Tukey-Kramer’s method followed all the above ANCOVA models for multiple comparisons among the groups at day 11.

Next, we used the food source from E. coli OP50 to Lactobacillus plantarum, a well-known probiotic strain that has been shown to extend lifespan in C. elegans26. When cranberry juice concentrate was supplemented with L. plantarum, only 0.016% the cranberry juice concentrate treated group showed a lifespan extension compared to the control (P < 0.0001); a median lifespan of 15 days and a maximum lifespan of 25 days (Fig. 2b). In health marker measurements, treatment of 0.016% cranberry juice concentrate with Lactobacillus had minimum effects on delaying the decline of average speed and maximum speed but showed significant delay on the drop of pumping rate and bending rate compared to the control group (Suppl. Fig. S5). On the contrary, the treatment of 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate with L. plantarum did not affect lifespan compared to the control. Still, it had a significant impact on health markers; delayed the decline of average speed, maximum speed, pumping rate, and bending rate compared to the control group (Suppl. Fig. S6). These results suggest that lifespan and health status can be differently influenced by various treatments.

Healthy aging evaluation using the quality-adjusted values

Previously, a limited number of studies have determined the healthspan of C. elegans19,20,21,22,23. However, the definitions used for ‘healthspan’ in these publications were inconsistent; 50% of maximum response20,23,38, arbitrary cut-offs21,23, developed a model system based on age-associated markers19, or suggested four stages of aging25. More importantly, these studies did not incorporate the lifespan data with age-associated markers even though survival is one of the critical factors of lifespan/healthspan except Hahm et al.38. Thus, we applied our results to the previously proposed ‘quality-adjusted value, Q(t)’ by Hahm et al.38 which was based on the work of Bansal et al.35. First, we calculated the Q(t) values from the control results by multiplying the survival rate with the bending or pumping rate after normalizing values using the bending or pumping rate from the first day of each group, designated as QB(t) or QP(t) (Eqs. 1 and 2), respectively.

The bending rate results from experiments testing cranberry juice concentrate and Lactobacillus were used to calculate QB(t) values. According to Fig. 2c and d, treatments’ effect on QB(t) may differ by day, and the pattern of change in QB(t) for each treatment is nonlinear over days. Thus, we consider a polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA model with treatment, polynomials of day, and their interactions. We have found that the overall effects of treatment (P < 0.0001) and days (P < 0.0001 for each of the linear, quadratic and cubic effects of days) are significant, and their interactions (P < 0.0001 for each interaction between treatment and days) are also significant.

Although the scale of days is different between treatments, we perform a multiple comparison among the treatment group at day 11 as a representative based on the observation that this is the mean lifespan of the control group. We observe significant improvement of QB(t) values by cranberry treatments only and cranberry juice 0.016% with Lactobacillus compared to the control, but not 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate with the Lactobacillus co-treated group (Fig. 2g).

Next, we calculated QP(t) using pumping rates of cranberry and Lactobacillus experiments. Figure 2e and f indicate that the effects of treatment on QP(t) depend on days, and the QP(t) pattern for each treatment is curvilinear over days. Using a polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA model with treatment, polynomials of day and their interactions, we have found that overall effects of treatment (P < 0.0001) and days (P < 0.0001, P < 0.0326 and P < 0.0001 for each of the linear, quadratic and cubic effects of days, respectively) are significant, and their interaction effects (P < 0.0485 for interaction between treatment and linear effect of days and P < 0.0001 for interaction between treatment and quadratic effect of days) are also significant.

From the multiple comparisons among the treatment group at day 11 as a representative based on the observation that this is the mean lifespan of the control group, we observed significant improvement of QP(t) values by cranberry treatments and 0.016% cranberry juice concentrate with Lactobacillus compared to the control (Fig. 2h). However, 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate with the Lactobacillus co-treated group was not different from the control group (P = 0.8207, Fig. 2f & h). These results of QP(t) were consistent with those of QB(t), confirming these two health-span markers are compatible.

Healthy aging analysis using newly defined dynamic-scaled values

The above quality-adjusted values (multiplication of natural survival rate and normalized health-related markers) are based on the assumption that survival rate and health-related markers contribute equally to the healthy status at any given time (Fig. 2c-f), which may be considered a limitation. For example, if a treatment extends lifespan at the expense of health-related markers, the quality-adjusted value would still indicate an overall improvement in healthspan, provided the increase in lifespan outweighs the decline in health markers. Thus, an alternative method is needed to objectively capture the significance of both lifespan and health markers. However, comparing the treatment’s effect on health markers over time inevitably includes the influence of lifespan, making it difficult to assess them independently. To overcome this limitation, we propose using new values: normalizing the health marker values with control values at comparable survival rates. We defined these as ‘dynamic-scaled’ values (Eqs. 3–4 in the method section). By using these dynamically scaled values, we can assess whether any additional changes in health markers are due to the treatment, beyond the changes that occur independent to an alteration of lifespan, as reflected by the survival rate.

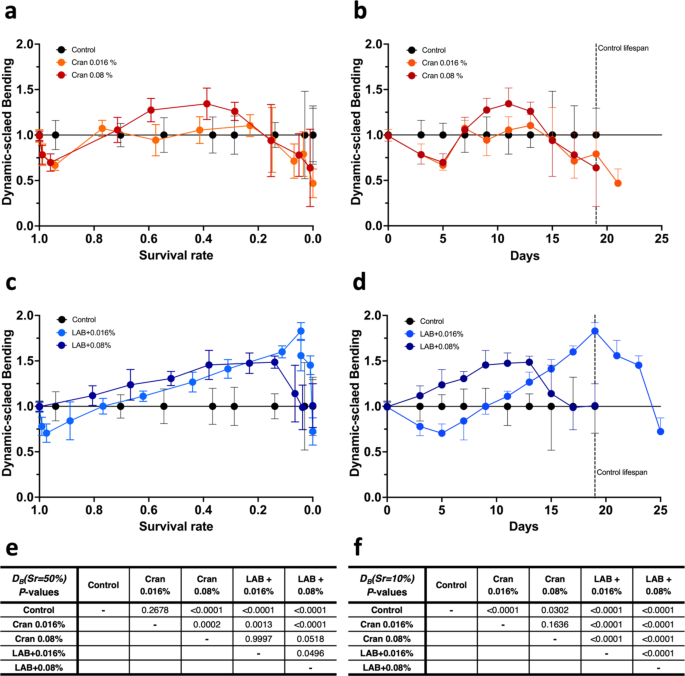

Using Eq. 3, we first calculated DB(Sr) by dividing bending rate of the treatment group over bending rate of the control group at the same survival rate and plotted it based on survival rate or time (Fig. 3). These figures show control as a flat line, thus, a relatively simple representation of the results; above is considered positive, and below represents negative in general. Figure 3a and c show that the DB(Sr) pattern changes are different according to the treatments and appear to be nonlinear over survival rates. Thus, all calculated data of DB(Sr) were analyzed by polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA models with treatment, polynomials of survival rate, and their interactions (Suppl. Fig. S7). The overall effects of treatment (P < 0.0001) and survival rates (P = 0.5084 and P < 0.0001 for the linear and quadratic effects of survival rates, respectively) are significant (Suppl. Fig. S7), and their interactions (P < 0.0001 for each interaction between treatment and survival rate) are also significant.

Dynamic-scaled values with the bending rate with various treatments in wild-type C. elegans. Dynamic-scaled values with bending rates, DB(Sr), were calculated as Eq. (3) and plotted over (a and c) survival rate and (b and d) corresponding time as days. Treatments included cranberry juice concentrate (Cran, 0.016 or 0.08%) with or without L. plantarum (LAB). Dashed lines in Figures (b and d) indicate the maximum lifespan of the control. Values represent means ± S.D. (n = 16). (e and f) The DB(Sr) data were analyzed using polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA models with treatment, survival rate, and their interactions.

We perform multiple comparisons among the treatment group at two survival rates, 50%, and 10%, as representatives of the mid-life and the end-of-life stages. At survival rates of 50%, we observe significant improvement of DB(Sr) values by the treatments compared to the control, except 0.016% cranberry juice concentrate only (Fig. 3e). It is also found that DB(Sr) values by 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate only and with Lactobacillus are significantly improved, compared to the 0.016% cranberry juice only (Fig. 3e).

For 10% survival rates, we first observe that DB(Sr) values by cranberry juice only are significantly lower than the values of the control, while DB(Sr) values by cranberry juice with Lactobacillus are higher than the values of the control (Fig. 3f). We also observe that DB(Sr) values by cranberry juice concentrate with Lactobacillus are higher than the values of the cranberry juice only (Fig. 3f). These results indicate that the improvement of health markers associated with these treatments was beyond its effects on extending lifespan.

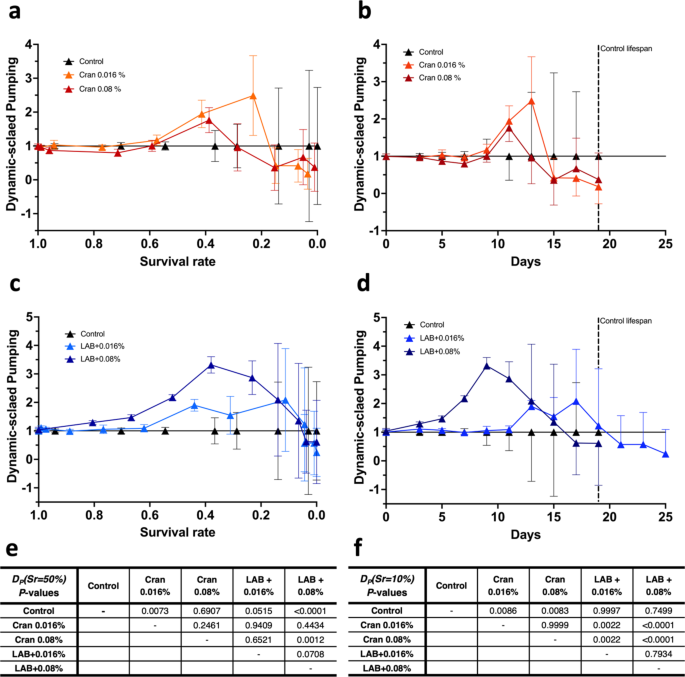

In addition to using bending rates to determine healthy status, we also evaluated pumping rates for dynamic-scaled values, DP(Sr). As discussed earlier, the pumping rate can be used in experiments with certain strains exhibiting impaired locomotion, including bending rate. From Fig. 4, we see the more considerable variation of DP(Sr) values in general, especially from the mid-late stage of life, likely caused by zero values of pumping rates (Suppl. Fig. S8). To address this, all calculated DP(Sr) values were analyzed using the Tweedie polynomial ANCOVA model with treatment, polynomials of survival rate, and their interactions. We found that the overall effects of treatment (P < 0.0001) and survival rates (P < 0.0001 for each of the linear, quadratic, and cubic effects of survival rates) are significant, and their interactions (P = 0.0002 for interactions between treatment and linear/quadratic effects of survival rate, respectively) are also significant (Suppl. Fig. S8).

Dynamic-scaled value with pumping rate with various treatments in wild-type C. elegans. Dynamic-scaled values with pumping rates, DP(Sr), were calculated as Eq. (4) and plotted over (a and c) survival rate and (b and d) corresponding time as days. Treatments included cranberry juice concentrate (Cran, 0.016 or 0.08%) with or without L. plantarum (LAB). Dashed lines in Figures (b) and (d) indicate the maximum lifespan of the control. Values represent means ± S.D. (n = 12). (e and f) The DP(Sr) data were analyzed using polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA models with treatment, survival rate, and their interactions. The polynomial Tweedie ANCOVA model was performed for the DP(Sr) data.

Similarly to the bending rate data, we perform multiple comparisons among the treatment group at two survival rates, 50% and 10%, as representatives of the mid-life and the end-of-life stages. At survival rates of 50%, we observe significant improvement of DP(Sr) values by 0.016% cranberry juice only and 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate with Lactobacillus compared to the control (Fig. 4e). It is also found that DP(Sr) values by 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate only are significantly lower, compared to 0.08% cranberry with Lactobacillus (Fig. 4e).

For 10% survival rates, we find that DP(Sr) values by cranberry juice concentrate only are significantly lower than the control (Fig. 4f). In addition, DP(Sr) values of 0.016% cranberry juice concentrate only are significantly different from cranberry juice concentrates with Lactobacillus (Fig. 4f). DP(Sr) values of 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate only are significantly different from cranberry with Lactobacillus (Fig. 4f). However, we need to note that the results for 10% survival rates would be less reliable due to more considerable variability and many zero pumping rate values.

Overall, the current results show that the treatment of 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate with Lactobacillus co-treatment group was not able to show significant improvement in health status when the quality-adjusted values were used, but when dynamic-scaled values were used, we see improvement in health status. This suggests that the results of dynamic-scaled values may be advantageous for presenting healthy aging in C. elegans.

Discussion

Lifespan extension alone does not necessarily suggest an overall improvement in health. Thus, there is a great need to understand the health of the aging process, which is defined as healthy aging. In this study, we evaluated various health markers currently in use in aging studies in C. elegans. Our result showed that commonly used muscle-associated health markers showed a high correlation with lifespan, and using either bending or pumping rate alone may represent the health status of C. elegans. Furthermore, we proposed using the dynamic-scaled value, normalizing the health marker values with those of control at the comparable survival rate. This is the first report to use the dynamic-scaled value, which is advantageous in determining healthy status by simultaneously considering lifespan and health markers.

Previously, research groups developed the Frailty Index as an assessment of healthy aging status in humans and mice16,17. From these, it is apparent that certain health markers are common between models, while others are unique to each model. This suggests that when using an animal model, focusing on health markers that are consistent within a model are important. In aging studies with C. elegans, previous publications determined the healthspan of C. elegansusing various health markers19,20,21,22,23. However, the definition of health-span used in these publications was inconsistent, nor were lifespan results incorporated into health-span determination except one by Hahm et al.38. Alternatively, focusing solely on lifespan may overlook the impact of the quality of life in aging. Thus, it is crucial to consider both lifespan and healthspan. This was reflected in a previous publication by Hahm et al.38, where the Q(t) value, multiplying the survival rate with a health marker, was used, assuming that lifespan and health markers are equal weights. However, when we applied Q(t) values in evaluating various conditions, we found that Q(t) values significantly depended on lifespan results. For example, we observed significant improvement in health markers of 0.08% cranberry juice concentrate and Lactobacillus co-treatment without altering lifespan, but Q(t) did not show any meaningful changes. These show that Q(t) values may not be able to distinguish the effect of any treatment on health markers that are independent of lifespan. Recognizing this limitation of Q(t) values, we introduced a new concept, which was proposed as dynamic-scaled values. This method normalized health marker values against comparable values from the control at similar survival rates, better representing the significance of lifespan and health markers. Thus, this approach may be used to interpret experimental results of determining the impact of various treatments on health status during aging and compare results of the differential contributions of lifespan and healthy aging.

Based on the inconsistent use and definition of health markers in previous research25,26,35,47, we also evaluated and determined various markers currently in use and concluded that using either bending or pharyngeal pumping rate would be a representative marker for the health of C. elegans. This would be a great advantage as measuring the bending or pumping rates is relatively simple and does not require specialized equipment and/or software. In addition, calculating the dynamic-scaled values would minimize interlaboratory variations as these will adjust health markers with their controls. However, we observed a relatively high standard deviation in dynamic-scaled value with pumping rate, particularly at a lower survival rate. This is because there is no detectable pumping rate at later life stages. This may have caused challenges in statistical analysis in DP(Sr), particularly in the mid-to later stage of life. In contrast, no similar issues were found with bending rate, which suggests that bending rate is more robust to determine the healthy aging status using the dynamic scale values. However, in cases where experiments were conducted with certain strains that exhibit impaired bending rate, pumping rate can still be alternatively used to calculate dynamic-scaled pumping DP(Sr) by using Tweedie ANCOVA with heterogeneity or with square root transformation to handle the significant variation caused by the zero pumping rate values observed at the later lifespan. Alternatively, low or zero pumping rate values can be arbitrarily cut off to remove the challenges that occur due to zero values observed in the pumping rate.

While our study provides valuable insight into healthy aging studies, it is not without limitations. Our approach of using a single health marker in determining healthy aging would have a great advantage as measuring both bending and pharyngeal pumping are very easy. However, the specific health markers chosen in this study may not represent the full spectrum of aging-related physiological changes of C. elegans. Thus, other health markers, such as autofluorescence, stress resistance capacity, mitochondrial activity, and potential locomotion markers19,25,35,38, that we did not evaluate in the current study should be tested in future studies. It is also possible that additional health markers beyond what we have tested are needed to improve healthspan determination.

In addition, our results are from a single experiment. Thus, to determine any significant treatment effects, it is necessary to collect more data for statistical analysis, as well as develop the definition of ‘healthspan’. Next, the current study used a liquid medium while C. eleganscan be also maintained in NGM plates, where two conditions would lead to different study outcomes, including lifespan48. However, using liquid culture conditions would be beneficial to study the effects of various treatments, particularly when culture medium needs to be changed regularly by using Transwell as we have previously used49. Nonetheless, when the results of dynamic scale values were compared, the experimental conditions of C. elegans, liquid vs. NGM, should be also considered.

It is also acknowledged that we did not have a group with L. plantarum only. Although we selected this based on the previous report in improving both lifespan and healthspan by L. plantarum26, including a treatment with L. plantarum only would have improved the overall understanding of the current results. Nonetheless, our current findings still provide results of interaction on bioactive compounds and bacteria on additive/synergetic effect or neutralizing the health beneficial effect. Thus, additional investigations of interventions’ additive and/or synergetic effects, such as cranberry juice concentrate and Lactobacillus, may unveil potential targets for therapeutic interventions to promote healthy aging.

Lastly, C. elegans is a model organism with many advantages in its short lifespan and genetic manipulations [13], however, it may limit the direct translation to higher organisms, including humans. Yet, the advantages of using C. elegans in the research, including relatively easy data collection for bending rate and pumping rate, both of which can be measured without special equipment or technique, will open accessibility of healthy aging studies with C. elegans to many researchers.

In conclusion, the proposed dynamic-scaled value may offer a novel method to determine healthy aging by integrating lifespan with health markers. This study is expected to advance the aging research field, emphasizing the importance of collective consideration of lifespan and healthy aging.

Materials and methods

Materials

Ampicillin was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), 5-fluoro-2’-deoxyuridine (FUDR) is from Research Products International (Mountain Prospect, IL), and household bleach was purchased from a local store. All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific Inc. (Pittsburgh, PA, USA). C. elegans N2 Bristol (wild-type) strain and Escherichia coli OP50 were purchased from Caenorhabditis Genetics Center (Minneapolis, MN, USA). Cranberry juice concentrate was received from Ocean Spray (Lakeville-Middleboro, MA, USA). Lactobacillus plantarum BAA-793 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA).

C. elegans culture and maintenance

As previously described, the nematode growth media (NGM), M9 buffer, and S-complete solutions required for C. elegansculture and maintenance were prepared49. E. coli OP50 was cultured daily using Luria-Bertani broth and incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. C. elegans strain was grown on NGM plates with live E. coli OP50 and incubated at 20˚C. Synchronized L1-stage worms were collected as described9. L1-stage worms were grown to L4-stage in S-complete for experiments.

Probiotic culture and maintenance

deMan Rogosa Sharpe (MRS) medium was used to culture L. plantarum. To reduce residual oxygen in the MRS medium to mimic anaerobic conditions, 0.05% of L-cysteine was added. L. plantarum in MRS medium was incubated at 37˚C for 24 h. Live L. plantarum was obtained every other day when changing media.

Lifespan assay

Approximately 10 worms were seeded in each well of 96-Transwell® plate in groups, and lifespan assay was started on the first day of adulthood. Media was changed every other day to maintain proper food level, and 120 µmol/L of FUDR was added to prevent eggs from hatching from day 1 of the adult stage. Total of 250 µL media mix containing S-complete, E. coli OP50, FUDR, and treatment was added to each well. Worms were incubated at 20˚C. Worms with no movement of both head and tail were gently touched using a platinum picker to confirm survival and worm survival was counted every other day until all worms were determined dead.

Measurements of health markers

Synchronized L4 stage worms were seeded on a 6-well culture plate with S-complete and fed live E. coli OP50 and incubated at 20˚C. Worms were kept in the same condition as in the lifespan assay above. S-complete media was changed every two days and maintained 2 ml of total volume per well. Randomly selected worms were used to measure health markers. The pharyngeal pumping rate was determined by counting the pharyngeal muscle contraction under an optical microscope (Nikon SMZ745 Stereo Microscope, Nikon Instruments Inc., Melville, NY)9,50. Locomotion behavior with crawling movement of speed, peristaltic speed [(total distance – reverse distance)/time], amplitude, and wavelength were measured every other day using automatic tracking system model MSCOP-002 from WormLab (WormLab, MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA) and analyzed using WormLab software 3.1.0, 64-bit (WormLab, MBF Bioscience, Williston, VT, USA) as previously described19,50,51. The bending rate was recorded by counting each bend generated during swimming under an optical microscope52.

Quality-adjusted value

Quality-adjusted value, Q(t), is defined as the natural survival rate, Sr, adjusted by multiplying the normalized health-related metrics at corresponding times, following the published work by Hahm et al.38. In the current study, bending rate (B) and pumping rate (P) were used as the representative health markers after normalized to the corresponding maximum value of each group, represented as B* and P*, respectively. Specifically, quality-adjusted values based on bending rate, QB(t), and pumping rate, Qp(t), were calculated as follows:

Dynamic-scaled value

The newly proposed dynamic-scaled values aim to evaluate a treatment’s effect on health-related metrics independent of its influence on the natural survival rate. Instead of using time, we explicitly assess the treatment’s impact by examining the relationship between health-related metrics and the natural survival rate. Our dynamic-scaled value is defined as the ratio of health-related metrics under the treatment to those under the control, calculated when the survival rates are the same. Therefore, the scale changes dynamically as the survival rate changes from 1 to 0.

Specifically, the dynamic-scaled bending DB(Sr) and the dynamic-scaled pumping rate DP(Sr) are defined as follows:

When the survival rate between the control and treatment groups did not match precisely in our experiment, we used piecewise linear interpolation to obtain the corresponding values for the scales. For the control, the control values were used instead of treatment; thus, all control values resulted in 1.

Statistical analysis

Lifespan data were analyzed using Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) tests using GraphPad Prism ver. 10.0.3 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). We sought to understand how each health marker is correlated to the others with respect to age. Correlations between different health markers as they change with age were quantified using Pearson’s correlation using DataFrame.corr() from the pandas package in Python. Pearson’s correlation matrix was then used to obtain a hierarchical clustering (Fig. 1o). The hierarchical clustering were obtained for three different groups of representing for the degree of correlation between health markers based on the distance matrix.

Analysis for pumping rate, average speed, maximum speed, peristaltic speed, average amplitude, maximum amplitude, average wavelength, maximum wavelength, and bending rate was performed using Mann-Kendall test (Kendall’s tau correlation) to assess the trend of each health metric over day.

The data of QB(t) and QP(t) were analyzed by the polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA (analysis of covariance) model with treatment (5 experimental groups, including the control group), time, and their interactions. The linear, quadratic, and cubic polynomial functions over the whole domain of time were used in the model to account for the curvature effect of time properly.

The DB(Sr) data were analyzed using polynomial heterogenous ANCOVA models with treatment, survival rate, and their interactions. The model used linear and quadratic polynomial functions over the whole domain of survival rate to properly account for the potential nonlinear effect of survival rate. The polynomial Tweedie ANCOVA model was performed for the DP(Sr) data to properly handle a non-negligible number of zero-valued observations occurring later in life. First, second, and third-order polynomial functions were considered in the model to consider the curvature effect of survival rate. Tukey-Kramer’s method followed all the above ANCOVA models for multiple comparisons among the treatment groups at different time/survival rates. The data above (QB(t), QP(t), DB(Sr), and DP(Sr)) were analyzed by PROC MIXED, PROC GLIMMIX, and PROC GENMOD of SAS software (Copyright @ 2023 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), and P < 0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Responses