Developing anti-TDE vaccine for sensitizing cancer cells to treatment and metastasis control

Introduction

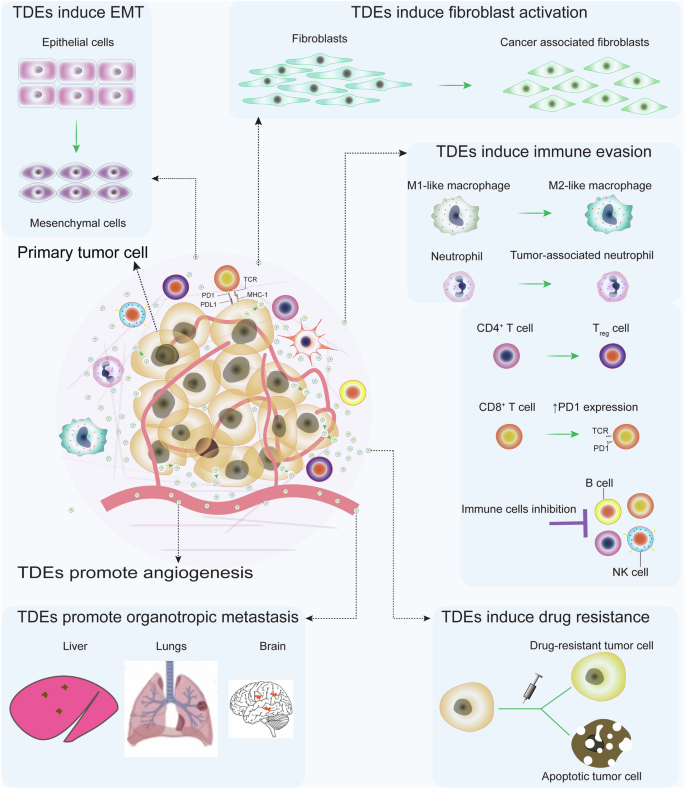

Metastasis is the greatest threat from cancer and is the leading cause of death related to malignancies1. Despite ongoing efforts to improve the potency of anti-cancer drugs, available conventional cancer therapies exhibit challenges that include treatment resistance, off-target toxicities, and limited efficacy in metastatic tumors2,3,4. Importantly, tumor-derived exosomes (TDEs) have been identified as key players in cancer growth, organ-specific dissemination, and treatment resistance5. TDEs convey oncogenic cargo that includes functional proteins and nucleic acids to their target cells, thereby promoting angiogenesis, immunosuppression, inflammation, drug resistance, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), invasiveness, and organotropic metastasis6,7,8 (Fig. 1).

TDEs mediate pro-tumorigenic communication that promotes immune evasion, tumor invasion, epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), angiogenesis, metastatic dissemination, and treatment resistance. TDE carries oncogenic messages to recruit and program stromal cells in the TME to express pro-tumorigenic phenotypes. Therefore, blocking TDE-mediated carcinogenic communication by inhibiting their biogenesis and uptake by target cells prohibits tumor-stromal cell crosstalk from controlling tumor growth, invasion, metastasis, and therapy resistance. This figure was generated using the Adobe AI tool.

It is also evident that oncogenic cargos shuttled by TDEs can induce malignant transformation of normal recipient cells in the local and distal milieu9,10. For instance, TDEs secreted by pancreatic cancer cells were able to initiate the malignant transformation of normal NIH/3T3 mouse fibroblasts through the induction of random mutations11. Apart from malignant transformation, TDEs promote cancer metastasis by orchestrating extracellular matrix remodeling to facilitate tumor cell migration12. Similarly, TDEs carrying miR-122 have been reported to regulate metabolism in the tumor microenvironment (TME) of breast cancer by reducing glucose uptake by normal cells and increasing its availability to cancer cells13. This is facilitated by miRNA-122-mediated downregulation of pyruvate kinase in normal cells, leading to inhibition of glycolysis and reduction in glucose uptake.

TDEs have also been demonstrated to mediate key processes in the initiation and progression of EMT, a phenotypic transition that endows tumor cells with the ability to migrate and metastasize. EMT is characterized by the downregulation of epithelial markers and upregulation of mesenchymal markers through epigenetic and post-translational modifications14. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are key orchestrators of EMT through their ability to modulate multiple signaling pathways that include NF-κB, TGF-β, Twist1, Notch, SNAIL, and Wnt15,16. The EMT-promoting effects of TDEs are mediated through their ability to influence the M2 polarization of TAMs. For instance, miR-106b-5 from colorectal cancer (CRC)-derived TDEs induces the M2 polarization of TAMs through suppression of programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4), leading to an activation of the PI3Kγ/AKT/ mTOR signaling pathway17. In turn, the M2-polarized TAMs enhance the EMT of CRC cells by downregulating their E-cadherin while upregulating their N-cadherin and vimentin expression17.

The TDE-mediated crosstalk between CRC cells and M2-polarized TAMs establishes a positive feedback loop that exacerbates and sustains CRC’s ability for migration, invasion, and metastasis17. Similarly, miR-3591-3p from glioma TDEs causes M2 polarization of macrophages by targeting the CBLB gene and mitogen-activated protein kinase 1 (MAPK1) with subsequent activation of JAK2/PI3K/Akt/mTOR and JAK2/STAT3 pathways18. Other cargo types have also been implicated in the M2 polarization of TAMs. For instance, TDE-derived pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) from hypoxic lung cancer cells facilitates the M2 polarization of TAMs by activating the AMPK pathway19. Consequently, the M2 macrophages promoted EMT of lung cancer cells by the downregulation of E-cadherin and upregulation of N-cadherin and vimentin19. Therefore, the TDE-mediated crosstalk between tumor cells and TAMs induces the M2 polarization of TAMs, the M2-polarized TAMs in turn induce EMT in tumor cells. This creates a positive feedback loop that promotes EMT in tumor cells.

The TDE-driven EMT of tumor cells significantly increases the circulating tumor cells (CTCs) and metastatic nodule formation in target organs. High expression of CD163, a marker of M2 TAMs, has been associated with a high number of CTCs in the peripheral blood of CRC patients20. TDEs influence the biology of CTCs from their formation to metastatic colonization including TDE-mediated ECM remodeling, disruption of vascular barriers, and angiogenesis which promotes the invasion of the stroma and shedding of CTCs21,22. The disruption of vascular barriers occurs through the TDE-mediated transfer of miRs and lncRNAs that downregulate the expression of tight junction proteins such as zonula occludens-1, vascular-endothelial cadherin, p120-catenin, claudin-1, and endothelial vinculin23,24,25. This disrupts the integrity of vascular-endothelial cells, uncontrollably and sustainably increasing vascular permeability, thus enhancing tumor cell intravasation to form CTCs. Furthermore, TDEs have been shown to enhance vascular permeability at distant target organs which can facilitate CTC’s extravasation26. The TDE-mediated EMT-CTCs crosstalk implies that therapeutic strategies that effectively block the TDE biogenesis and/or uptake will effectively control CTC generation and metastatic colonization.

The role of TDEs extends to include the facilitation of organotropic metastasis, that is TDEs determine the specific organ for CTC metastasis. Mechanistically, it has been elucidated that cargoes shuttled by TDEs play important roles in guiding CTCs to secondary organs27. For example, during lung metastasis of breast cancer, α6β1 and α6β4 integrins shuttled by TDEs upregulate the expression of S100 protein in lung fibroblasts and epithelial cells to initiate the formation of pre-metastatic niche27. Similarly, αvβ5 integrins shuttled by pancreatic cancer TDEs drive liver metastasis by initiating metastatic niche formation through stimulation of expression of S100 protein in Kupffer cells27. Furthermore, TDE-conveyed αvβ3 integrins have been implicated to propagate the migration and adhesion of prostate cancer cells to bone matrix protein and vitronectin, facilitating metastatic tumor growth28. These examples highlight the role of TDEs in orchestrating organotropic metastasis, for comprehensive insights into the role of TDEs in organotropic metastasis, refer to the following reviews16,29.

It is obvious that treating primary tumors with conventional therapy alone without inhibiting the TDE-mediated exchange of oncogenic cargo is inadequate given the role played by TDEs in stimulating cancer progression. Although the primary aim of cytotoxic therapy is to induce tumor cell death, some tumor cells take other fates such as senescence and quiescence, which allow them to continue the secretion of TDEs that promote the malignant progression of surviving viable tumor cells30,31. Current strategies to inhibit TDE-mediated oncogenic communication including drug-based and genetic modification-based inhibition of TDE release and/or uptake, have proved to be inefficient. In this work, we propose surface engineering of TDEs to express foreign antigens that will trigger life-long anti-TDE immune responses. The possibilities of combining the anti-TDE vaccines with other treatments such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy, and surgery are also explored.

Current strategies for inhibiting TDE-mediated communication in tumors

Inhibition of TDE biogenesis and release by tumor cells

There is substantial evidence to support the notion that inhibition of TDE secretion by tumor cells has the potential to control tumor progression and prevent metastasis. Particularly, the pharmacological inhibition of TDE secretion by prostate cancer cells using GW4869 led to the inhibition of tumor progression by impairing the M2 polarization of TAMs32. Likewise, inhibition of the secretion of TDEs that shuttle programmed cell death ligand-1 (PD-L1) limited tumor growth, favor anti-tumor immune activation and augment the activity of anti-PD-L1 monoclonal antibodies by improving their sensitivity to tumor cells33,34. A long list of pharmacological agents that can inhibit TDE secretion by blocking one or multiple processes along the biogenesis and release pathways have been reported. Here, we provide a brief overview of the inhibitors of TDE secretion that have undergone thorough testing in pre-clinical studies, for comprehensive reviews of inhibition of exosome secretion, refer to the following publications35,36,37.

Pharmacological inhibition of TDE biogenesis and release

The biogenesis of TDEs follows the same pathways as exosome generation under physiological conditions. Unlike normal cell-derived exosomes, TDEs are enriched in tumor cell-derived biomolecules including proteins, nucleic acids, and metabolites38. Exosome biogenesis begins with the invagination of the plasma membrane to form early endosomes, which mature into late endosomes39. The late endosomes subsequently generate multivesicular bodies (MVBs) through the inward budding of their limiting membrane. The MVBs can then either fuse with lysosomes for degradation or fuse with the plasma membrane to release their intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) as exosomes into the extracellular space40. The processes of exosome biogenesis are tightly regulated and involve distinct molecular mechanisms, such as the endosomal sorting complex required for transport (ESCRT) machinery, ceramide-mediated sorting, and tetraspanin-mediated formation. These molecular mechanisms and pathways provide targets for inhibition of exosome biogenesis. For instance, Calpeptin is a pharmacological agent that inhibits calpain. Calpain is a family of calcium-dependent neutral, cytosolic cysteine proteases. Usually, calpain is deregulated in malignant cells to promote tumor invasion and progression35,41. The calpain proenzyme is activated into proenzyme upon binding of calcium, which plays a role in regulating the functions of various proteins such as G-proteins and cytoskeletal proteins. By regulating cytoskeletal proteins, calpain stimulates the release of MVBs. Impeding the functions of calpain by calpeptin drugs results in the reduced release of MVBs and subsequently limits the release of exosomes/TDEs by cells35. The literature shows that blocking the cellular release of MVBs by calpeptin significantly improved tumor cell killing by increasing the intracellular accumulation of chemotherapy. Similar results were reported in pre-clinical studies, whereby combination therapy with calpeptin and docetaxel significantly reduced tumor mass compared with a single use of docetaxel alone35.

Several small molecule inhibitors of TDE biogenesis have shown encouraging results in pre-clinical studies (Table 1). GW4869 is one of the widely reported small molecule inhibitors of TDE biogenesis that acts through attenuation of the budding of intraluminal vesicles (ILVs) into MVBs by inhibiting neutral sphingomyelinase 2 (nSMase2)enzyme42,43. nSMase2 catalyzes the hydrolysis of membrane sphingomyelin to produce ceramide and phosphocholine44. The released ceramide plays multiple roles in TDE biogenesis including ILVs budding and fusion of late endosomes and cell membranes for TDE secretion45. In PC-3M-2B4 and PC-3M-1E8 prostate cancer cells, GW4869 treatment led to significant impairment of TDE release and was associated with decreased M2 polarization of TAMs32,46.

Heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPGs) play key roles in the biogenesis of exosomes. In particular, syndecan and its binding partners, syntenin and ALIX regulate exosome biogenesis by supporting the budding of intraluminal membranes of endosomes during the formation of ILVs, which are precursors to exosomes47. Thus SyntOFF binds the PDZ-domain of syntenin and inhibits TDE secretion by blocking the interactions of syntenin and its binding partners48. This interferes with the syndecan-syntenin-ALIX-dependent formation of endosomal ILVs and exosome biogenesis. In vitro treatment of MCF-7 cells with SyntOFF resulted in significant changes in TDE cargo with decreased syntenin, SDC4, and ALIX, which was associated with a decrease in proliferation, migration, and spheroid formation abilities of the MCF-7 cells48. Like SyntOFF, tipifarnib inhibits exosome biogenesis by targeting the syndecan-syntenin-ALIX interactions with additional targets including neutral sphingomyelinase (nSMase), and ROCK-dependent pathways49. Tipifarnib is a farnesyltransferase (FTase) inhibitor with potent anti-cancer and anti-parasitic effects and has been approved for the treatment of HRAS-mutated squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Tipifarnib has shown potent, tumor cell-specific inhibitory effects on TDE secretion in C4-2B and PC-3 prostate cancer cell lines, which were not observed in the normal prostate RPWE-1 cell line49.

Another important druggable target to inhibit the biogenesis of TDEs is the endothelin (ET)-endothelin receptor A (ETA) signaling pathway, which influences multiple downstream pathways of the ESCRT-dependent MVB biogenesis as well as controls the fusion of MVBs and lysosomes50. Several small molecule inhibitors of this pathway have been identified and tested in pre-clinical models of inhibiting TDE-mediated communication. For instance, macitentan (MAC) is a potent inhibitor of ET1 binding to its receptors ETA and ETB that has gained FDA approval for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension51. In vitro treatment of MDA-MB 231 cells with MAC significantly reduced EV secretion and PD-L1 content of secreted EVs52. Similar findings were obtained in vivo using the MDA-MB 231 xenograft model. Sulfisoxazole (SFX) is another pharmacological inhibitor of the endothelin-endothelin receptors pathway which has shown potent inhibition of TDE generation in vivo52,53. In MDA-MB 231 and 4T1 mouse models of breast cancer, SFX treatment resulted in a significant reduction of circulating EV concentration and was associated with inhibition of tumor growth, metastasis reduction, and increased animal survival53. However, the inhibitory effects of SFX on TDE secretion could not be replicated by another group of investigators54. Therefore, further studies are warranted to clarify the conflicting findings.

Given the significance of lipids as key structural components of EVs, perturbations in lipid biosynthesis and/or transport have a direct impact on EV secretion. Several approved anti-lipidemic drugs have shown efficacy in decreasing the secretion of TDEs by tumor cells. Simvastatin and atorvastatin are approved cholesterol-lowering drugs that act by inhibiting the HMG CoA reductase, an enzyme that catalyzes the rate-limiting step of cholesterol biosynthesis. Cholesterol depletion following simvastatin or atorvastatin treatment leads to suppression of TDE biogenesis in treated tumor cells55. Particularly, atorvastatin enhanced the cytotoxic effects of paclitaxel (PTX) in vitro in the SK-OV-3 cell line and xenograft models by blocking exosomal drug shedding56. On the other hand, indomethacin is a non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is used for the treatment of a wide range of inflammatory conditions. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) by indomethacin leads to perturbation of proteins involved in cholesterol transport including the 27-hydroxylase and the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 (ABCA1), leading to reduced intracellular cholesterol availability57. In vitro treatment of B cell lymphoma cells with indomethacin decreased their EV secretion and was associated with improved intracellular retention of doxorubicin and pixantrone, with concomitant increase in their cytostatic effects58.

Ketoconazole (KTZ) is yet another approved drug that can be repurposed for inhibition of TDE generation by tumor cells. KTZ is an antifungal drug that is widely used to treat dermatological fungal infections. KTZ inhibits TDE secretion by targeting multiple pathways including the syndecan-syntenin-ALIX, Rab27, ERK1/2, and nSMase59. In C4-2B and PC-3 prostate cancer cells, KTZ led to potent tumor-specific inhibition of TDE biogenesis while showing no effect in normal prostate RPWE-1 cell line49. This tumor cell selectivity is a distinct advantage shown by KTZ, which can potentially reduce the off-target effects of exosome inhibition in normal cells.

In addition to the inhibitors of TDE biogenesis, another group of small molecule inhibitors block the shedding of TDEs from the cell-surface membranes. Proteins of the cytoskeleton play an important role during the release process. For instance, actin and myosin microfilaments play key roles in vesicle trafficking and release processes that lead to their release from the cell-surface membrane60. Several small molecule inhibitors of TDE release work by targeting the cytoskeletal proteins. For instance, bisindolylmaleimide-I (BM-1) is a cell-permeable, highly potent, and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C (PKC) with strong inhibitory effects on TDE release61. PKC, along with other members of the rho-associated protein kinase (ROCK) family is required to trigger myosin contraction during vesicle release from the plasma membrane62. Treatment of PC-3 prostate cancer cells with BM-1 resulted in significant inhibition of TDE release that resulted in increased drug retention and tumor cell apoptosis63. Cl-amidine is another small molecule inhibitor that exerts its effects through modulation of the cytoskeletal proteins. Cl-amidine is an inhibitor of peptidyl arginine deiminases (PAD), enzymes that catalyze the post-translational deimination of proteins by converting arginine residues to citrulline. PAD-catalyzed deimination (citrullination) of cytoskeletal proteins such as actin and myosin leads to alteration of their contractile properties, thereby diminishing their ability for trafficking and cell-surface release of vesicles37,64. Cl-amidine inhibition of TDE and microvesicle release in the PC-3 cancer cell line resulted in increased drug retention and tumor cell apoptosis63.

Ceramides, which are products of sphingolipid metabolism generated from the cleavage of membrane sphingomyelin by sphingomyelinase enzymes, are known to play important roles in the biogenesis and release of extracellular vesicles. EV release occurs at ceramide-rich microdomains of the cell membrane which facilitates the fusion of endosomes and cell-surface membrane during EV secretion45. Inhibition of ceramide generation has proven to be an effective strategy to block the release of extracellular vesicles from the cell-surface membrane. Similarly, imipramine is an antidepressant medication with strong inhibitory effects on the acid sphingomyelinase (aSMase) enzyme, which interferes with the shedding of vesicles from the plasma membrane65. In the PC-3 cell line, imipramine treatment inhibited the secretion of both small and large-sized extracellular vesicles63. Other small molecule inhibitors that exert their effects through the ceramide pathway include GW4869 and spiroepoxide42,43,66. Thus, inhibition of TDE secretion and uptake by target cells suppresses TDE-mediated communication, which also reverses drug resistance by sensitizing cancer cells to treatment66.

Genetic engineering strategies for inhibition of TDE biogenesis and uptake by target cells

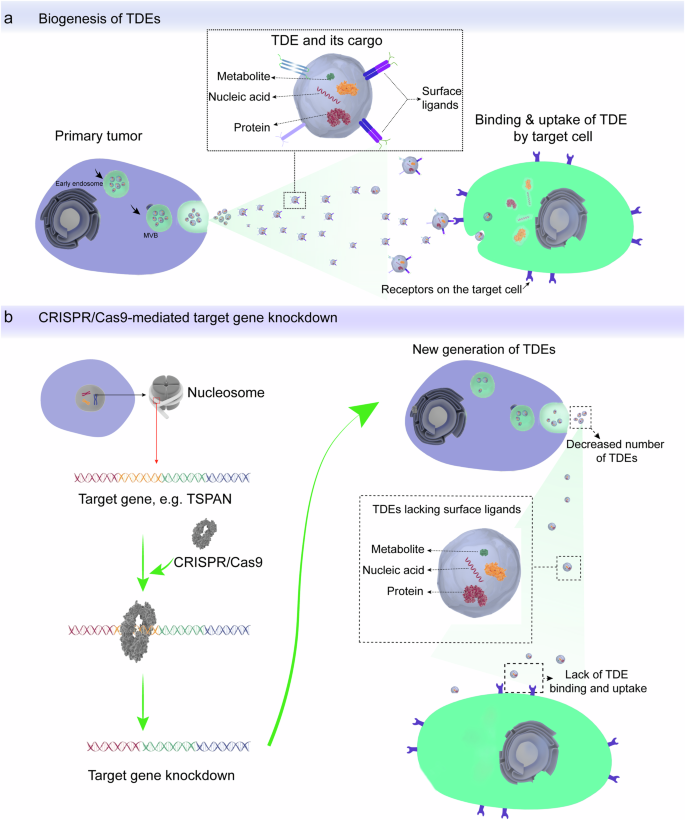

Genetic engineering techniques can be applied to manipulate tumor cells to either diminish their TDE secretion, secreting immunogenic TDEs or secrete TDEs with impaired ability to bind target cells (Fig. 2). The advantages of genetic engineering approaches over pharmacological approaches include the possibility of achieving durable and tumor cell-specific suppression of TDE secretion. The inhibition of TDE secretion is achieved by genetically modifying tumor cells by knockdown or repression of genes whose products are involved in the biogenesis and release of TDEs. Techniques that can be used to modify gene expression in tumor cells include CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockdown, viral vectors, and RNA interference (RNAi) techniques. For instance, potent inhibition of TDE secretion can be achieved by CRISPR-Cas-9-mediated knockdown of Rab27a and nSMase2 genes in the mouse prostate carcinoma cell line (TRAMP-C2)67. Furthermore, RNAi-mediated silencing of proteins of the ESCRT machinery including hepatocyte growth factor-regulated tyrosine kinase substrate (HRS), signal transducing adapter molecule 1 (STAM1), and tumor susceptibility gene 101 (TSG101) led to a significant reduction in TDE secretion in HeLa-CIITA-OVA cells68. These results show the potential of genetic techniques to achieve durable repression of TDE inhibition that can provide long-term control of TDE-mediated pro-tumorigenic signaling.

a The processes of TDE biogenesis, release, and uptake by their target cells. b Knockdown of genes involved in TDE biogenesis and recognition by target cells can block TDE-mediated pro-tumorigenic communication by suppressing both secretion and uptake of TDEs. This figure was generated using the Adobe AI tool.

Genetic manipulations can also reduce the uptake of secreted TDEs by their target cells. This is achieved by the knockdown of genes whose products are involved in the selective binding of TDEs to their target cells. Tetraspanins and integrins are families of transmembrane proteins that are enriched on TDE membranes and are known to play important roles in the binding of TDEs to their target cells. In particular, tetraspanins, which are among the proteins enriched in EVs69,70,71, are involved in key processes during the binding of EVs with their target cells, including adhesion, binding, and vesicular membrane fusion72,73,74. Tetraspanin proteins CD63, CD9, CD81, and Tspan8 promote the proliferation and migration of cancer cells, angiogenesis, remodeling of extracellular matrix, and pre-metastatic niche formation75,76. The knockdown of tetraspanin expression in tumor cells can therefore reduce their concentration in secreted TDEs, which will impair the uptake of TDEs by their target cells. For instance, RNAi-mediated knockdown of CD151 and Tspan8 was effective in impairing the uptake of TDEs by multiple target cells in a rat model of pancreatic carcinoma. Knockdown of CD151 disrupted several tumorigenic processes, including matrix remodeling, tumor cell invasion, migration, EMT, and metastatic colonization74. Similarly, knockdown of Tspan8 and/or CD151 was associated with diminished EMT, angiogenesis, invasiveness, migration, and metastatic colonization in autochthonous and syngeneic mouse models of MCA-induced tumors77.

Integrins are another family of membrane proteins that are enriched on TDE membranes and can be similarly silenced as tetraspanins. For instance, integrin beta-1 (ITGB1) and integrin-associated protein CD47 are enriched in EVs78,79 and are involved in the uptake of TDEs by their target cells. However, a major challenge to genetic engineering strategies is that most of the TDE-enriched proteins are not globally abundant and ubiquitous, and show heterogeneity among tumor types79. Thus, the selection of target proteins should be tailored according to the proteomic characteristics of TDEs or EVs for each patient, and multiple targets can be used to increase the TDE inhibition efficiency.

The CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing technology can be used to achieve stable and durable in vivo gene knockdown, facilitating the clinical translation of the genetic manipulation strategies. The CRISPR-Cas9 technology offers the possibility to knock down multiple genes by using multiple short guide RNAs80,81. Furthermore, the high targeting specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 technology lowers the risk of off-target insertional mutagenesis and its associated adverse effects82. Therefore, we are suggesting engineering primary tumor cells by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated deletion of genes encoding specific exosomal surface proteins that play critical roles in targeting TDEs to specific cells. For instance, knocking down the gene encoding exosomal tetraspanin protein CD151 impairs the selective uptake of TDEs by target cells. Notably, expression of CD151 in TDEs is associated with tumor invasion and metastasis75,77. Thus, the knockdown of CD151 will block the uptake of TDE by target cells, thereby limiting cancer progression by inhibiting TDE-mediated oncogenic signaling (Fig. 2b).

In addition, normal exosomes can be engineered to target cancer cells and used as vehicles for the targeted delivery of vector-bearing transgene of interest and CRISP-Cas9 to the tumor cells83,84. This is because exosomes have intrinsic biocompatibility and high tissue penetration ability. Thus, EVs are good tumor-targeting vehicles and can be engineered to target cancer cells for safe and selective drug delivery purposes85,86,87,88. From this perspective, we also propose the use of engineered normal exosomes for the targeted delivery of an expression vector-bearing transgene of interest and CRISP-Cas9 to both primary and secondary tumors. The use of engineered cancer-targeting EVs will allow secure packaging of expression vectors and CRISPR-Cas9 to enable efficient, safe, and selective delivery to the tumors, thus preventing off-target delivery to normal cells.

Challenges with existing strategies for inhibiting TDE-mediated communication in tumors

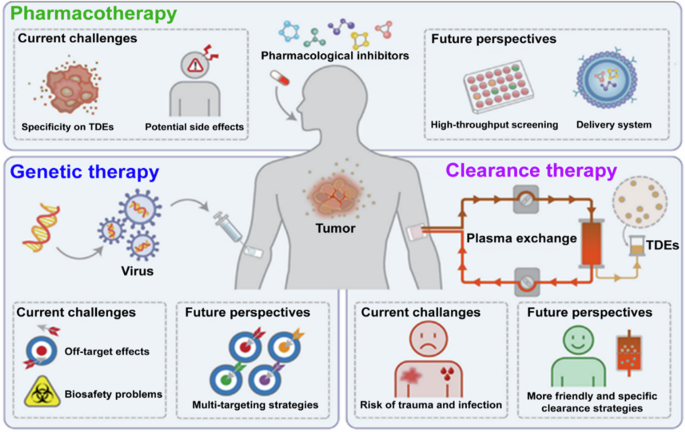

Targeting TDEs with the strategies discussed so far including pharmacological inhibition and genetic modification has drawbacks that hinder their effectiveness (Fig. 3).

Off-target toxicity is the major challenge reported in all methods used to target TDE and the development of a tumor-targeting delivery tool is suggested as a solution. The development of clinically available pharmacological inhibitor-based tumor therapies will be promoted by combining high-throughput drug screening strategies and targeted drug delivery systems. The trauma and risk of infection, bleeding, and removal of normal exosomes associated with extracorporeal TDE clearance can be avoided with the development of targeted immune-based clearance. This figure has been reproduced from Li et al. 95, with permission from Experimental & Molecular Medicine.

For instance, inhibition of TDE secretion and uptake by target cells using the drug-based approach is limited by the lack of long-term optimal therapeutic efficacy due to hepatic drug metabolism and renal excretion. Due to the continuous secretion of TDE from tumor cells, including tumor cells that have undergone therapy-induced senescence (TIS), an effective anti-TDE therapy must be able to achieve continuous and durable effects. Another concern with pharmacological agents is safety regarding their off-target toxicity37. In addition to liver metabolism and off-target toxicity, the wide use of pharmacological agents produces unreliable results because they only target one or two molecules involved in either TDE biogenesis, release, or uptake. However, tumor cells can develop compensatory mechanisms that can bypass the inhibited pathways to continue TDE secretion for oncogenic signaling37.

Furthermore, the majority of pharmacological inhibitors of TDE secretion target the same pathways that are involved in EV secretion in normal cells, resulting in a lack of specificity in TDE inhibition. Given the roles played by EVs in the regulation of diverse normal physiological processes, inadvertent inhibition of EV-mediated communication will have detrimental health effects. Important physiological processes that can be affected by EV inhibition include inflammation and immune responses, angiogenesis and wound healing, reproduction and development, regulation of gene expression, and host-microbiome interactions89. On the other hand, inhibition of TDE secretion by genetic engineering carries the risks of adverse immune reactions and off-target effects resulting from insertional mutagenesis or gene deletions in normal cells. For example, the use of viral vectors such as adenovirus and lentivirus during genomic editing to inhibit TDE secretion may lead to adverse immune responses due to host-virus interactions90,91. However, the utilization of DNA transposons as expression vectors offers several advantages over viral vectors including effectiveness in generating stable genome integration, lack of immune rejection, and the ability to transfer large genetic sequences91,92. Particularly, the PB transposon has a high transposition activity and a good site specificity for transgene integration into the target cell genome93,94.

Lastly, the elimination of TDEs by extracorporeal methods is traumatic and compromised by the risk of infections and bleeding. Another critical setback of extracorporeal-based clearance of TDEs is the inability to achieve durable and complete elimination of TDEs, as well as the high risk of eliminating exosomes released by normal cells that are required for normal cellular functions95.

Perspectives for developing anti-TDE vaccine by engineering primary tumor cells

To address the aforementioned challenges, we present our perspective for developing an anti-TDE vaccine to stimulate acquired anti-TDE immunity. The advantage of using the anti-TDE vaccine strategy over conventional strategies of inhibiting TDEs based on drug therapy and genetic engineering is the ability to achieve long-term clearance of TDEs specifically but not normal cell-derived exosomes. This provides a durable control of TDE-mediated oncogenic communication that restricts cancer progression. The immunogenicity of TDEs largely depends on the immunogenicity of tumor cells secreting them. The immunogenicity of tumor cells depends on their expression of tumor-specific antigens (TSAs), mutated or lineage-restricted proteins whose expression is confined to tumor cells96,97. TDEs are generally weakly immunogenic because of the low immunogenicity of the tumor cells, which is a result of the progressive loss of TSAs by immunoediting98,99,100. Therefore, generating highly immunogenic TDEs would require the incorporation of highly immunogenic foreign antigens such as viral antigens that lack homology and cross-reactivity with human proteins. Fortunately, there is a long list of candidate proteins from common viruses that have shown high immunogenicity as virus-like particles (VLPs), including hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen (HBsAg), human papillomavirus (HPV) L1 protein, HEV’s PORF2 protein, IAV’s hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) proteins, HIV’s p17 and p21 of HIV, and HPVB19’s VP1 and VP2 proteins101.

The generation of exosome-based vaccines carrying viral proteins has been previously reported102. For instance, the decoration of exosomes with a recombinant receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) generated a potent vaccine that triggered robust humoral and cell-mediated anti-SARS-CoV-2 immune responses102. Similarly, robust anti-viral immune responses were generated using engineered DC-derived exosomes expressing M187–195 and NS161–75 immunodominant peptides from the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)103. These studies underscore the potential of exosomes carrying foreign antigens to trigger robust immune responses.

Traditionally, vaccines were made using components of the target invader such as weakened or killed microbes and their toxins. However, the recent success with mRNA-based vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 has opened the possibilities for vaccine generation by genetic engineering104,105. Thus, instead of mRNA injection, genes encoding the target protein can be inserted into host cells and, their expression will stimulate immune responses similar to those achieved using mRNA vaccine. Tumor cells can thus be transfected with viral genes, and the products of these genes will ultimately be included in secreted TDEs106. To enhance the localization of the viral antigens on the surface of TDEs, the viral genes can be fused to human genes whose protein products are known to localize on the surface of TDEs. Owing to high heterogeneity in proteomic contents among different TDE populations107,108, a suitable human gene to fuse with the viral gene should be ubiquitously present in secreted TDEs. The universal proteomic biomarkers of EVs identified by quantitative proteomics include members of the tetraspanin, ADAM, ADAMT, ESCRT, and PDZ families78,109. In particular, the tetraspanins including CD9, CD63, CD81, and CD82 as well as syntenin-1 and syndecan-4 are highly abundant in extracellular vesicles of endosomal origin109. Since TDEs are mainly generated through the endosomal pathway110,111, these proteins can effectively ensure the localization of foreign antigens to the surface of diverse populations of TDEs. For instance, the coding region of HBV HBsAg can be fused with the coding region of CD63 to produce a fusion protein that will be localized on exosome membranes by adopting similar techniques as described by Duong et al. 69,112.

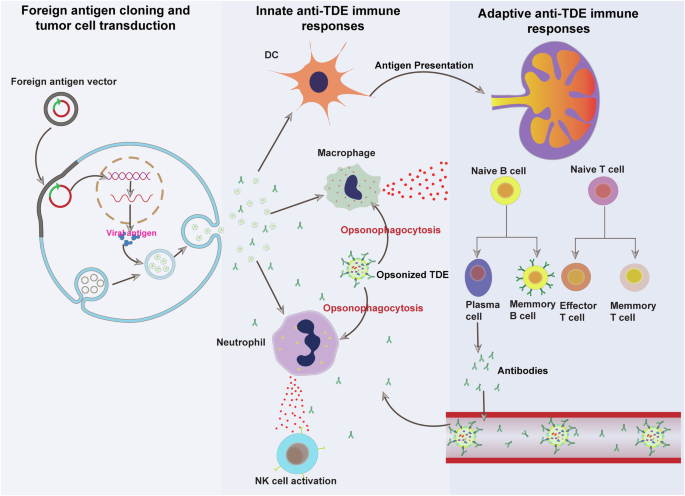

HBsAg is an attractive candidate viral antigen because its use as an HBV vaccine has proven its ability to induce optimal immune responses with an acceptable safety profile113,114. Engineering of HBsAg-expressing TDEs can stimulate both innate and adaptive anti-HBV immune reactions by inducing antigen-specific cytotoxic T cell responses, activation of neutralizing antibodies, phagocytosis, and cytokine-mediated anti-viral activity115. The innate immune responses are elicited upon the recognition of viral proteins, in this case HBsAg, by toll-like receptors (TLRs) on the surfaces of innate immune cells including macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes. Once activated, these innate immune cells are involved in phagocytosis and secretion of a multitude of chemical mediators including Type-I interferons (IFN-α and IFN-β) and pro-inflammatory cytokines (PICs) such as TNF-α, which activate natural killer (NK) cells. Adaptive immune responses will be activated through the presentation of HBsAg by DCs and macrophages to T and B cells resulting in the generation of viral antigen-specific T and B cells116. This would result in both humoral and cell-mediated immune reactions against viral antigens (Fig. 4). The cell-mediated immune responses, mediated by cytotoxic T cells will mainly be directed to the engineered tumor cells that express viral antigens and will have little impact on secreted TDEs. Whereas antibody-mediated responses bear more significance in the elimination of viral antigen-expressing TDEs115,117,118,119. The antibody-dependent effector functions of significance in TDE clearance include opsonization, neutralization, antibody-mediated macrophage, and neutrophil activation as well as opsonophagocytosis120. The activation of the anti-HBV immune reaction will therefore facilitate the rapid elimination of modulated TDEs after their secretion to prevent the transfer of their oncogenic cargo to their target cells, which will impair the TDE-mediated oncogenic signaling.

Candidate viral antigen genes are cloned in plasmid or transposon vectors and transduced to tumor cells. The foreign protein is expressed by modified tumor cells and is incorporated into the outer membrane of secreted TDEs. The foreign protein expressing TDEs are engulfed by phagocytic innate immune cells including macrophages, neutrophils, and dendritic cells. The engulfed foreign antigen is processed and displayed on the surface of mature dendritic cells. Mature dendritic cells migrate to the tumor draining lymph nodes to present the viral antigens to T and B lymphocytes. Antigen presentation results in the activation of antigen-specific B and T cells. Activated B cells differentiate into antibody-secreting plasma cells and long-lived memory B cells. Secreted antibodies bind to cognate antigens displayed on TDEs to tag them for phagocytosis by neutrophils and macrophages. PIC pro-inflammatory cytokine and DC dendritic cell. This figure was generated using the Adobe AI tool.

The success of the strategy will largely depend on the ability to engineer the majority of tumor cells to secrete immunogenic TDEs that will be eliminated by the immune system both locally and systemically. Therefore, identifying the right molecular tools that would enable this objective is of paramount importance. Several types of vectors can be used to achieve a stable transduction of solid tumors with foreign genes. Both viral and non-viral vector systems are widely used biological tools to modify the genome of target cells for a permanent expression of the gene of interest (GOI)121,122. The commonly used viral vectors include adenovirus (AV), adeno-associated virus (AAV), and lentivirus (LV). However, the clinical use of viral vectors is limited by virus clearance by anti-viral immune responses and their risk of insertional mutagenesis90,91. On the other hand, non-viral vectors such as polymers, liposomes, lipids, peptides, and inorganic nanoparticles have lower risks of cytotoxicity, immunogenicity, and mutagenicity92,123. Several genome editing tools can be dispatched using non-viral delivery systems including DNA transposons, zinc finger proteins, transcription activator-like effectors, and CRISPR-Cas. Compared to other non-viral genome editing tools, DNA transposons offer the advantage of stable long-term transgene expression due to their ability to integrate into the genome91,92,124,125.

In particular, the PiggyBac (PB) transposon vector is a preferred transposon vector due to its efficiency in transferring large genetic units, high transposition activity, high site specificity for transgene integration, and the lack of inhibition of overproduction93,94. The PB transposon has been widely utilized to generate chimeric antigen receptor T (CAR-T) cells during ex-vivo expansion of T cells. Under ex-vivo conditions, high CAR transduction rates of up to 81% were achieved using PB transposon and electroporation126,127,128. Several PB transposon-edited CAR-T cell products have entered early-phase clinical trials including CARCIK-CD19 cells for the treatment of relapsed B cell lymphoblastic leukemia, SLAMF7 CAR-T cells for the treatment of multiple myeloma and piggyBac CAR19 T cells for relapsed or refractory B cell malignancies129,130,131. Similarly, a PB transposon-derived prime editing platform (piggyPrime) yielded up to 100% prime editing efficiencies in HeLa, K562, and HEK293T cell lines132. Furthermore, in vivo studies of PB transposon-mediated demonstrated efficient integration and stable expression of transgenes. For instance, utilizing PB transposons in combination with a mouse codon-optimized PB transposase, was successful in a pre-clinical mouse model study in achieving durable expression of the factor IX (FIX) gene for over a year and curing hemophilia B, a bleeding disorder in mice with defective FIX gene133. Similarly, PB transposon-based genome editing yielded a 70% efficiency in transgene integration in marmoset embryonic stem cells following injection into the perivitelline space and electroporation134. Thus, available evidence suggests PB transposon-based tools can achieve high transduction efficiencies and can be useful for the transduction of viral antigen transgenes to tumor cells. Transduction efficiencies can be further improved by physical methods such as electroporation, sonoporation, magnetoporation, and optoporation135.

In summary, we propose a strategy for the inhibition of TDE-mediated oncogenic communication through immune clearance of secreted TDEs. Owing to the low immunogenicity of naturally secreted TDEs, this strategy requires modification of tumor cells to secrete highly immunogenic TDEs. This can be achieved by inserting genes for potent viral antigens in tumor cells, which will result in the incorporation of the viral antigens into the surface of the secreted TDEs. Although we have focused our discussion on HBsAg, other candidate viral antigens can also be used in the same way and it’s difficult to predict which antigen will yield the best results.

Clinical benefits and anticipated limitations of the anti-TDE vaccine

Cancer metastasis is responsible for up to 90% of all cancer-related deaths136 and TDEs play crucial roles in the metastatic dissemination of cancer. A large body of evidence shows the involvement of TDEs in tumor cell EMT, invasion, migration, and metastatic dissemination by translocating oncogenic cargoes such as TGF-β, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α), β-catenin, or vimentin, casein kinase, and miRNAs137. Thus, tumor invasion and spread will be significantly controlled by anti-TDE vaccine by preventing TDE-mediated shuttling of EMT-inducing agents to target cells. The anti-TDE vaccine will also improve anti-tumor immunity by turning immunologically cold tumors into hot ones. This is because the expression of highly immunogenic viral antigens by tumor cells will improve antigen presentation and lymphocyte infiltration of tumors. Furthermore, the ant-TDE vaccine will help to overcome the immunosuppressive effects of TDEs such as suppression of immune cell proliferation, induction of apoptosis in activated CD8+ T cells, inhibition of the activity of natural killer cells, and impedance of the differentiation of monocytes138. Therefore, effective elimination of TDEs by anti-TDE vaccine will significantly improve anti-tumor immune responses in the tumor microenvironment (TME). The other clinical benefit of the anti-TDE vaccine is the improvement of the sensitivity of cancer cells to conventional therapy. This is because TDEs promote the development of treatment resistance138, so their elimination will reverse therapy resistance.

Another important consideration regarding the rationale of our proposed anti-TDE vaccine strategy is the relative importance of anti-TDE immunity over anti-tumor immunity resulting from modified tumor cells expressing viral antigens. It is well-established that solid tumors can employ robust immune escape mechanisms to resist clearance by the immune system139,140. Even highly immunogenic tumors expressing tumor-specific antigens of viral origin can avoid killing by cytotoxic T cells. A typical example of immune escape by tumor cells expressing highly immunogenic viral antigens is provided by adenovirus-induced hepatocellular carcinoma expressing SV40 large T antigen (TAg)141. In these tumors, immune tolerance develops despite continued TAg expression and a high infiltration with cytotoxic T cells141. Similarly, engineered expression of lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV) glycoprotein (GP) by tumor cells failed to produce sustained anti-cancer CTL responses despite the persistence of GP expression142. Furthermore, during an oncolytic virus therapy with herpes simplex virus (HSV), failure to activate robust anti-cancer immune reactions may occur despite productive and persistent virus infection of tumor cells143. These examples underline the importance of multi-pronged approaches to effectively control tumor growth and spread. The tumor cells that escape immune clearance will continue to secrete immunogenic TDEs, which can be easily eliminated outside the suppressive tumor microenvironment. In this context, the generation of immunogenic TDEs will still be beneficial to attenuate their metastatic-promoting effects to either delay or prevent the metastatic dissemination of tumor cells that may ultimately escape immunosurveillance.

It is also noteworthy to consider the risks of the proposed anti-TDE vaccine compared to the other established TDE inhibition strategies. The potential safety concerns of this strategy include the risk of off-target insertion of the transgenes as well as interference with normal cell exosome secretion and uptake. Exosome-mediated intercellular communication regulates diverse physiological processes such as inflammation and immune responses, angiogenesis and wound healing, reproduction and development, regulation of gene expression, and host-microbiome interactions89. Although clinical data on the detrimental effects is scarce, the possibility of interfering with multiple physiological processes necessitates the use of strategies with high TDE selectivity. Compared to pharmacological inhibition, the anti-TDE vaccine strategy offers the potential possibility for long-lasting TDE-specific elimination, which is difficult to achieve with drug-based inhibition. TDE-specific inhibition can be achieved by targeted delivery of therapeutic gene vectors using tools such as modified normal exosomes that can specifically target cancer cells85,86,87,88. This reduces the risk of inadvertent modification of normal cells which could result in clearance of normal exosomes. Furthermore, the risk of off-target insertion and insertional mutagenesis can be reduced by using DNA transposons instead of viral vectors due to their good site specificity of transgene integration into the target cell genome83,84.

Practical limitations such as high production costs due to the complexity of the vaccine manufacturing will likely affect affordability to the majority of cancer patients144,145. The use of cheaper, yet effective options such as PB transposons, can significantly reduce production costs and improve affordability91,92. Moreover, there will be risks of unanticipated adverse immune reactions to viral antigens in a subset of patients, this requires careful patient monitoring and early intervention. Also, vaccine-related side effects such as fever, nausea, and vomiting may be caused by immune responses due to anti-TDE vaccine products or reactions associated with vaccine quality defects are to be expected.

Combination of the anti-TDE vaccine with other cancer therapies

The use of combination therapies is commonplace in cancer management. In principle, combination therapy improves treatment efficacy by synergizing the anti-cancer activities of two or more cancer therapies. Given the role of TDEs as mediators of cancer therapy resistance146, combination therapies with the anti-TDE vaccine are a promising strategy to overcome therapy resistance. For instance, a large body of evidence implicates the PD-L1-positive TDEs as mediators of immunosuppression through its interaction with PD-1 receptors on cytotoxic T cells147. Thus, vaccine-mediated TDE clearance can suppress TDE-derived PD-L1 inhibition of cytotoxic T cells, promote T cell activation, and result in durable anti-cancer immunity67. This opens the possibility of combination therapies of anti-TDE vaccine with immune checkpoint inhibitors and cell-based immunotherapies.

TDEs also contribute to drug resistance by interacting with chemotherapy and promoting the expression of drug-resistance genes138,148. This is evidenced by TDE derived from gemcitabine-resistant pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) shuttled miR-155 to promote resistance to PDAC cells that are susceptible to gemcitabine149. Likewise, TDEs from chemo-resistant mesenchymal non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) induced resistance in chemosensitive cells150. Similarly, TDEs secreted by tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells were observed to transfer miR-221/222 to tamoxifen-sensitive breast cancer cells to induce resistance151. Pharmacological inhibition of TDE biogenesis enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of several cytotoxic drugs including sutinib, doxorubicin, pixantrone, paclitaxel, and bortezomib56,58,59,62,63,152. Thus, combining the anti-TDE vaccine and cytotoxic chemotherapy will likely yield similar synergistic effects to pharmacological inhibitors to overcome drug resistance in resistant tumors. The potential advantage of the anti-TDE vaccine is the possibility of reducing off-target effects due to its inherent TDE specificity.

In addition to sensitizing cancer cells to chemotherapy, blocking TDE-mediated communication by anti-TDE vaccine would enhance the susceptibility of cancer cells to radiotherapy. This is because TDEs mediate radioresistance in tumor cells through the promotion of the secretion of several factors that promote radioresistance153. Evidence shows that radiosensitive breast cancer cells can acquire a radioresistant phenotype through TDE-mediated paracrine signaling from radioresistant tumor cells153,154. Thus, vaccine-induced elimination of TDEs will potentiate the anti-tumor activity of radiotherapy by preventing the acquisition of radioresistance in tumor cells.

Furthermore, the anti-TDE vaccine has potential benefits in patients with locally advanced tumors that have been surgically removed. The occurrence of distant metastasis without local recurrence after a latent time suggests a potential benefit of metastasis-inhibiting therapy in these patients155. Thus, our proposed anti-TDE vaccine can be used in either adjuvant or neo-adjuvant settings in patients with locally advanced tumors undergoing surgical excision.

Interestingly, targeted cytokine therapy (TCT) has made enormous progress, showing promising results in several malignancies156,157,158,159,160. In TCT, the cytotoxicity of tumor-infiltrating T cells to tumor cells is enhanced by the delivery of immunostimulatory cytokines such as IFN-γ and IL-2 or by blocking tumor-promoting cytokines such as IL6, epidermal growth factor (EGF), vascular-endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β)156,157,158,159,160. However, the major hurdle facing TCT is the development of dose-limiting off-target side effects which are collectively referred to as immune-related adverse effects (irAEs)159. The pleiotropic nature of cytokine effects in vivo creates difficulties in predicting their off-target effects161. Intratumoral delivery can reduce the incidence of irAEs, although it is wider applicability is limited by the labor-intensive administration procedure162. Targeted delivery of the cytokines to tumors is therefore a prerequisite to effective TCT. The fusion of cytokines and tumor-targeting antibodies offers promise to improve tumor targeting of cytokines and reduce the incidence of irAEs163,164,165,166,167. However, this approach depends on high-affinity tumor-specific antigens (TSAs) that are difficult to find in most solid tumors. The high-affinity foreign antigen expressed by tumor cells engineered can thus be utilized for tumor targeting of cytokines. The process will involve the generation of immunocytokines of viral antigen-specific antibodies and anti-cancer cytokines such as IL-2 and IFN-γ. Thus, synergistic anti-tumor activity will result from cytokine-induced augmentation of tumor reactivity of exhausted intratumoral T cells and enhancement of tumor cell cytotoxicity due to the presence of high-affinity foreign antigens.

Implementation roadmap of the proposed approach aimed at targeting TDE-mediated communication

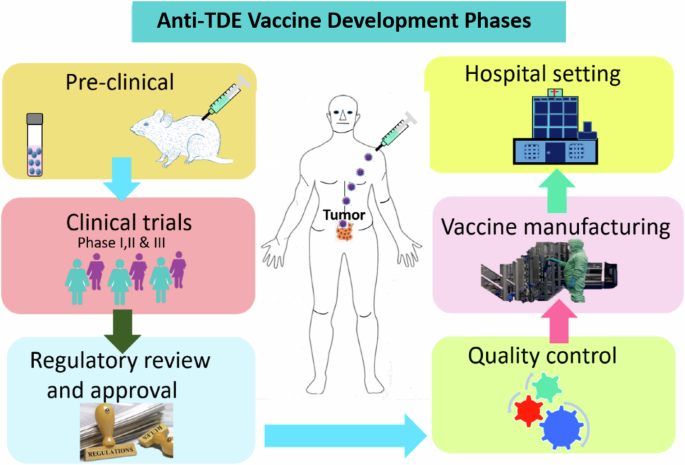

The scientific process of developing an anti-TDE vaccine will require multiple facilities including a virus engineering laboratory, cell culture laboratory, vaccine development laboratory, pharmaceutical facility, and cancer hospital as well as trained personnel (Fig. 5). Crucially, pre-clinical research studies require cell culture facilities and a biosafety level 2 (BSL-2) laboratory. An expression vector with GOI will be created for the pre-clinical research, and its effectiveness in modifying different cancer cell lines to release immunogenic TDEs will be evaluated. Moreover, EVs will be designed with precision to encapsulate and selectively deliver vectors expressing GOI. Thereafter, the in vivo studies will be employed to assess the anti-TDE vaccine’s effectiveness in animal models. Clinical trials to evaluate the vaccine’s immunogenicity, efficacy, and safety profiles in cancer patients recruited and qualified for enrollment will begin once the pre-clinical trial is successful. After completing phase III clinical trials and government approval, the vaccine will be mass-produced for hospital use. A clinical laboratory, pharmacy, and skilled labor force are needed in a hospital setting to administer and monitor the efficacy and side effects of the anti-TDE vaccine.

Facilities essential for vaccine development from research to clinical application include laboratories for pre-clinical and clinical studies, industries for producing vaccines, pharmacies for the vaccine supply chain, and hospitals for treating cancer patients. This figure was generated using the Adobe AI tool.

Conclusion

We propose a novel intervention of developing anti-TDEs vaccines, which impairs the TDE-mediated exchange of oncogenic cargo, thereby rendering TDE dysfunctional. Anti-TDE vaccine intervention involves manipulating primary and secondary solid tumors to secrete immunogenic TDEs that express foreign antigens on their surface, such as HBsAg. The surface expression of foreign antigens by TDEs results in the activation of the immune response for their clearance. To improve the efficacy of anti-TDE vaccine, we propose the engineering of tumor cells by knockout-specific genes, which are preferentially expressed by TDEs to facilitate their selective binding and uptake by target cells. By impairing selective binding and uptake by target cells, immunogenic TDEs will accumulate in the extracellular space for immune clearance. The dual arrest of TDE-mediated communication through restricted uptake of modified TDEs and immune clearance will certainly inhibit the exchange of oncogenic biomolecules involved in cancer growth, invasion, metastasis, and treatment resistance. Therefore, optimization of anti-TDE vaccine has the potential to limit tumor growth, spread, and sensitize cancer cells to treatment. This will tremendously extend the overall survival of cancer patients by averting metastasis and also providing the opportunity to treat the tumor effectively with surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and targeted therapies.

Responses