Development of accessible and scalable maize pollen storage technology

Introduction

Pollination is a critical step in the life cycle of agricultural crops and is required to produce the seeds, grains, and fruits that humans rely on. Pollen longevity is diverse across crop plant species, with agricultural fruit trees producing pollen that can survive for years1. On the opposite extreme, the pollen of Oryza sativa (rice) remains viable for as little as 4 min in the open air2. Zea mays (maize, corn) has been subject to decades of scientific plant breeding that has recognized the value of pollen storage for over one hundred years3, yet the inherent short lifespan of maize pollen still hinders germplasm improvement and hybrid seed production. Early studies demonstrated that desiccation and elevated temperatures were the most immediate threats to maize pollen viability4. The same work stored pollen in a saturated relative humidity atmosphere that slowed desiccation and demonstrated that pollen viability could be maintained for up to 48 h as opposed to pollen surviving only 2 h in the open air4. Further studies used cross-pollinations to demonstrate that maize pollen fertility could be maintained for three days if pollen were stored in a sealed vessel and at a lower temperature (0–14 °C)5. The stored maize pollen demonstrated a high rate of respiration in storage that released measurable amounts of carbon dioxide5. Knowlton’s work documented an early observation that stored maize pollen clumped together into a “caked” mass that was inefficient for pollination5. Later research confirmed that this high rate of cellular respiration in maize pollen was a key feature of trinucleate Gramineae pollens compared to binucleate pollens6. Later research utilized talcum (mineral talc powder) or heat-killed maize pollen as carrier compounds for situations requiring maize pollen storage and dilution7. The same work by Walden included experiments quantifying the impact on seed set when pollen was diluted by carrier compounds7. This study also observed that maize pollen longevity did not differ between inbreds and hybrids7. In a similar application focused on pollen storage for tree species, talcum was used as a dilutant in production scale pollen storage and application8.

Further efforts on maize pollen storage turned to precise pollen moisture content adjustment and cryogenic storage to preserve pollen viability for months to years. These efforts included extensive work by Beáta Barnabás using controlled airflow to adjust pollen moisture prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen9,10,11. Technology patented by the GARST Seed Company used an oscillating vacuum system to control the rate and endpoint of maize pollen desiccation prior to freezing in liquid nitrogen12. A common theme across 100 years of maize pollen storage research was the practical tradeoff between assessing pollen viability using low-cost, rapid methods that may be less predictive of seed set (in vitro germination using pollen germination media, diverse metabolic stains) and the slower, higher cost method of test pollinations to directly assess seed set13.

Investigation into hypothesized limiting factors specific to maize pollen viability have included pollen moisture content14 and issues with pollen adhesion to silks15. Researchers have made progress in understanding maize pollen tube growth16,17. These findings have so far not led to advancements in maize pollen storage technology. The technical complexity and cost of precisely controlling pollen desiccation and cryogenic storage serve as additional obstacles to scalability and commercial use in diverse global maize production environments. More recently, researchers have renewed focus on extending pollen viability for five days while avoiding the complications of long-term storage18,19.

Unfortunately, practical maize pollen storage has proven to be an elusive technology with limited impact on maize breeding and seed production. We hypothesized that not understanding the biological factors underlying maize pollen longevity in storage and a lack of technology scalability had hindered technology translation from research lab scale to application in breeding and hybrid seed production operations. This manuscript reports the results of an investigation into the key biological factors impacting maize pollen longevity in short-term storage. Accounting for these factors resulted in a method of maize pollen storage that can preserve maize pollen viability for up to seven days using low-cost, globally available materials. This protocol can serve the needs of breeders and production scientists working with diverse germplasm across a wide range of global maize production environments.

Results

Pollen respiration dynamics are linked to temperature

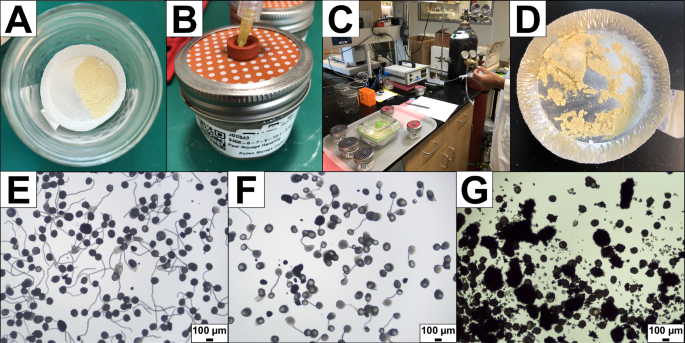

The team conducted experiments where maize pollen was stored in a metabolically active state in order to better understand the challenges of extending maize pollen lifespan. The team mixed fresh pollen from greenhouse-grown maize plants with talcum and stored the mixture in airtight jars equipped with a gas-sampling rubber septum (Fig. 1A, B). Sealed vessels were stored at room temperature (23 °C) or were placed into refrigerated storage at 2 °C or 6 °C at local atmospheric pressure (100.3 kPa). Endpoint storage vessel atmospheric gases (Fig. 1C) were measured between one to seven days of storage. Mold growth was visible after four days of storage at 23 °C (Fig. 1D) and researchers noted odors associated with fermentation. The team assessed pollen viability following storage using pollen tube germination media (Figs. 1E–G). Pollen tube germination on media completely ceased after three days at 23 °C. Samples stored at 2 °C retained viability for six days and samples stored at 6 °C remained capable of germination for seven days.

A Pollen mixed with talcum is placed onto an aluminum pan within a storage vessel. B A storage vessel modified to include a septum for vessel atmosphere gas sampling. C Nitrogen gas injection and gas sample analysis from diverse storage vessels. D Pollen stored at room temperature and standard atmospheric pressure shows mold growth after four days. E An example of high pollen tube germination on media using freshly shed pollen. F An example of intermediate pollen tube germination and pollen grain bursting on media using stored pollen mixed with talcum. G An example of burst and clumped, non-viable stored pollen on media using pollen mixed with talcum. Scale bars on images E–G are approximate.

Endpoint storage vessel gas analysis from pollen samples stored at 23 °C demonstrated a high metabolic gas exchange rate of 0.640 mmol oxygen (O2) and 0.602 mmol carbon dioxide (CO2) per gram of pure pollen per day (mmol g−1 day−1) averaged over the duration of storage (Fig. 2A). Storage at 6 °C depressed the metabolic gas exchange rate to 0.156 mmol O2 g−1 day−1 and 0.138 mmol CO2 g−1 day−1 (Fig. 2A). Storage at 2 °C further depressed the metabolic gas exchange rate to 0.104 mmol O2 g−1 day−1 and 0.091 mmol CO2 g−1 day−1 (Fig. 2A). A data logging thermometer placed in the pollen storage vessel incubator set to 2 °C revealed internal temperatures had dipped as low as 0 °C during compressor cycles. A similar trend of refrigerators set to 4 °C dipping to 0 °C was measured in other lab equipment. The team hypothesized that these short durations of freezing temperature contributed to pollen dying earlier in storage than similar samples stored at 6 °C. All subsequent experiments took place at 6 °C to avoid the risk of refrigerators and incubators freezing stored pollen.

A Metabolic gas exchange per gram of pure pollen per day in sealed storage vessels at standard atmospheric gas content (20.9% O2, <0.1% CO2,) at three different temperatures. Gas exchange rates reflect the average over the entire duration of storage. Connecting letters reflect Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05, n = 156 storage vessels. B Daily O2 use rates of maize pollen in sealed storage vessels at 6 °C using three different protocols. Averages include storage vessels ranging between 125 mL and 920 mL with storage durations ranging between one and seven days. Connecting letters reflect Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05, n = 135 storage vessels.

Metabolic gas exchange dictates storage vessel requirements

The pollen tube germination ratings collected following pollen storage decreased when over one gram of pollen was stored in a 125 mL storage vessel for seven days compared to lower quantities of pollen stored for the same duration in identical storage vessels (Supplemental Table 1). The team hypothesized that increasing CO2 concentrations produced by cellular respiration were causing this decreased pollen tube germination. The O2 concentration was reduced in storage without altering the ratio of atmospheric gasses in an effort to further depress pollen metabolism and reduce the accumulation of CO2. This was accomplished by removing whole air from storage vessels using a vacuum pump (pressure set to 60 kPa below standard atmospheric pressure at the testing location, 40 kPa absolute). Pollen stored at 6 °C in sealed vessels at partial vacuum successfully preserved pollen viability for up to seven days. This vacuum storage method did not significantly reduce the rate of O2 consumption by pollen in storage (Fig. 2B). Vacuum storage demonstrated the same trend of decreased pollen tube germination as the pollen quantity exceeded 0.36 grams of pollen per 125 mL of storage vessel headspace (Supplemental Table 2). A series of experiments that artificially increased CO2 in storage vessel atmospheres determined that CO2 toxicity to pollen was a complex interaction of concentration and duration in storage (Supplemental Table 3). From these findings, the team hypothesized that pollen viability began decreasing after 24 h within a storage vessel atmosphere consisting of ≥10% CO2 or independently consisting of ≤5% O2 content. These thresholds became the focus of further protocol development.

The team discontinued vacuum testing and efforts to further depress the pollen respiration rate. To reduce CO2 accumulation in storage vessels, the team evaluated six CO2 sequestration agents; soda lime, lithium hydroxide, ethanolamine, activated charcoal, Zeolite 4 A, and Florisil®. Soda lime, lithium hydroxide, and ethanolamine had a chemical mode of action in which CO2 reacts with a nucleophile to form a solid carbonate or carbamate in the presence of water20. Activated charcoal21 and Zeolite 4A22 functioned as molecular sieves and selectively trapped CO2 in angstrom-sized pores. The team included Florisil® (activated magnesium silicate trioxide, MgSiO3) based on the prior observation that mixing pollen with Florisil® reduced CO2 in a sealed pollen storage vessel. These agents were tested in identical sealed pollen storage vessels with an artificial 8% CO2 atmosphere. The 8% CO2 starting point was selected to model the time point during pollen storage where CO2 levels were hypothesized to soon begin negatively impacting pollen viability. As expected, sequestration of CO2 did not provide additional O2 during storage. Soda lime, lithium hydroxide, ethanolamine, and Florisil® were the most effective CO2 sequestration agents. All four compounds demonstrated the capacity to maintain a sealed storage vessel atmosphere at ≤0.01% CO2 (Supplemental Table 4). All further testing used soda lime to maintain a ≤ 0.01% CO2 atmosphere due to soda lime having a lower cost, global availability for purchase, and a favorable safety profile compared to alternatives. The team hypothesized that the increased rate of O2 consumption by pollen stored with soda lime (Fig. 2B) was the result of maintaining a more optimal storage vessel atmosphere free of excess CO2 over the entire duration of storage. Pollen stored using this sealed vessel protocol with soda lime produced a high seed set in test pollinations after up to seven days of storage (Supplemental Fig. 1).

Additional experiments tested ways to increase the amount of O2 available to stored pollen by adding pure O2 or whole atmospheric air to sealed pollen storage vessels. The addition of pure O2 into pollen storage vessel atmospheres did not increase pollination performance (Supplemental Table 5). The team observed that pollen stored in O2 concentrations of ≥43% demonstrated an up to 24-h delay in pollen tube germination when placed on media. A LACO helium bombing chamber (Supplemental Fig. 2) was used to demonstrate that maize pollen cannot survive prolonged storage at >3 total atmosphere of pressure when the storage vessel was pressurized using additional atmospheric air (≈78% N2, ≈21% O2, <0.1% CO2) (Supplemental Table 6).

Breathable barriers simplify pollen storage and optimize storage vessel efficiency

The above experiments clarified that the high metabolic rate of maize pollen was the critical factor limiting scalability. Large pollen storage vessels could preserve > 100 mL of pollen in a field trialing context using either vacuum storage or sealing the vessel with added soda lime (Supplemental Fig. 3A, B). Scaling this protocol up to pollinate an average seed production field would require thousands of liters of storage vessel space (Supplemental Fig. 4). The team took inspiration from common practices in plant tissue culture where there is a similar challenge of enabling plants to exchange gas with the outside atmosphere while preventing dehydration of the tissue culture media. The team hypothesized that the selective properties of breathable barriers similar to those used in plant tissue culture would prevent the buildup of CO2 and depletion of O2 within storage vessels and avoid excessive water vapor loss across the barrier that could lead to pollen death. The team selected Micropore™ cellulose tape based on use in plant tissue culture and Tyvek® (high-density polyethylene) film based on published gas exchange data from packaging material23. The team also evaluated small, circular, open perforations for controlled gas exchange. Micropore™ cellulose tape reduced water vapor loss by 23% compared to an open perforation, while Tyvek® reduced water vapor loss by 48% compared to an open perforation. Both types of breathable barriers and the open perforations demonstrated < 100 µg h−1 mm−2 rates of water vapor loss (Supplemental Table 7). Experiments demonstrated that >1.67 mm2 of breathable barrier per gram (mm2 g−1) of pure pollen was required to sustain pollen viability in storage based on the rate of O2 exchange across Tyvek® (Supplemental Table 8). Breathable barriers increased storage vessel O2 content and enabled high seed set from stored pollen, even when pollen volumes increased relative to the storage vessel headspace (Supplemental Table 9). These barriers enabled the entire storage vessel interior volume to be filled with pollen and resolved the issue of excessive storage vessel size limiting scalability to hybrid seed production (Supplemental Fig. 4).

The team stored one liter of maize pollen mixed with a carrier (estimated to contain one billion metabolically active pollen grains) in an unmodified cell culture flask to evaluate breathable barrier protocol scalability. The storage vessel headspace O2 content fell to <1% within the first hour after the vessel mouth was covered in cellulose Micropore™ tape. The vessel atmosphere stabilized at 14.8% O2 after 4 h at 6 °C, then measured at 13% O2 and 5% CO2 after five days of storage. A delay in pollen tube germination was observed at the conclusion of this experiment. The team hypothesized that this undesirable CO2 accumulation and the delayed pollen tube germination were due to the excessive distance over which gasses had to diffuse between the outside environment and across the breathable barrier to the stored pollen (274 mm from mouth to bottom of the flask) (Supplemental Fig. 5). To address this issue of excessive gas diffusion distance, the team reduced the distance by drilling twenty-eight 10 mm holes distributed around the surface of the container. These holes increased the total breathable barrier surface to 2290 mm2 from the 661 mm2 stock configuration and reduced the maximum distance between stored pollen and the nearest breathable barrier down to 47 mm (Supplemental Fig. 5). The 28 holes were covered in cellulose Micropore™ tape and this modified storage vessel was filled with one liter of pollen mixed with a carrier. The storage vessel atmosphere stabilized at 20.9% O2 after 4 h. The vessel atmosphere was at 18.7% O2 and 1.2% CO2 after six days of storage. There was no observed delay in pollen tube germination after storage in the modified cell culture flask and test pollinations resulted in a high seed set (Fig. 3). The team evaluated the modified cell culture flask design at the production scale in a hybrid seed production field trial in Elkhorn, Nebraska. The team collected two liters of pollen, and then equally divided the pollen into a modified and a stock configuration cell culture flask prior to storing the pollen for five days. Pollen stored for five days in the modified flask configuration produced over twice the seed compared to the one liter of pollen stored in an unmodified, stock configuration flask (Supplemental Table 10). Later experiments at the production scale used the modified cell culture flask design to preserve > 48 liters of pollen from hybrid seed production trials in Formosa, Brazil (Supplemental Fig. 3C).

A Complete seed set data for pollinations onto hybrid and inbred tester ears. n = 78 pollinated ears (B). Images of the best-pollinated ears, worst-pollinated ears, unpollinated negative checks, and open-pollinated positive checks for the hybrid and inbred testers.

Experiments over the entire duration of the project demonstrated that pollen storage technology was penetrant across temperate and tropical dent corn lines used in hybrid seed production. Summarized testing results indicated that pollen from over 90% of maize lines across four major heterotic groups survived for five or more days in storage (Supplemental Table 11). Pollen from the single sweet corn line included in testing survived for five days in storage.

Identification of superior maize pollen storage carrier compounds

The team observed that pollen mixed with talcum failed to produce a complete seed set on ≈25% of ears across hundreds of pollinations during early project experiments. Raw pollen, pollen mixed with talcum, and pollen mixed with Florisil® were compared using scanning electron microscopy (SEM), compound microscopy, and aniline blue staining (Supplemental Fig. 6). SEM demonstrated that talcum excessively coated maize pollen grains compared to Florisil® (Supplemental Fig. 6A, D, and G). Compound microscopy imaging of silks pollinated using a mix of pollen and talcum showed that the silk surface and trichomes were covered in loose talcum particles (Supplemental Fig. 6E). The team observed few pollen grains sticking to the silks compared to silks pollinated with raw pollen (Supplemental Fig. 6B, E). Aniline blue staining of the same silks pollinated with a mixture of pollen and talcum showed minimal pollen tube growth through the silk compared to silks pollinated with raw pollen (Supplemental Fig. 6C, F). Pollen mixed with activated magnesium silicate (Florisil®) showed similar adhesion between pollen grains and silks compared to raw pollen (Supplemental Fig. 6B, H). Aniline blue staining of silks from these pollinations visualized a similar pattern of pollen tube growth as those silks pollinated with raw pollen alone (Supplemental Fig. 6C, I). These observations suggested that talcum inhibited silk adherence and inhibited the pollen tube germination required for fertilization and seed set. In response to these findings, the team developed a two-part hypothesis in which 1) there is an optimal particle size for pollen storage carriers that inhibits pollen grains from sticking to one another yet does not block adhesion to silks; and 2) the carrier compound must not disintegrate into smaller particles during handling to avoid excessively coating pollen grains. Common forms of talcum fail to meet both of these criteria due to low mineral hardness and a <75 µm particle size that contains numerous <10 µm particles24.

Crystalline silica (mineral quartz) supplied at a 10 µm average particle size was the first compound identified by the team as meeting these two criteria. Storage experiments and test pollinations were conducted using 10 µm crystalline silica, <200 mesh (<75 µm) Florisil®, and a custom sample of talcum with a particle size range of 25–75 µm (produced using a US 500-mesh sieve). These experiments indicated that pollen mixed with crystalline silica delivered higher average seed sets than the same dosage of stored pollen mixed with talcum (Supplemental Fig. 7). The same experiments demonstrated that crystalline silica reduced the frequency of poorly pollinated (<100 kernels) ears compared to commercial talcum (Supplemental Fig. 7). SEM imaging suggested that crystalline silica was selectively aggregating around pollen grains that had burst during handling and storage and was not excessively coating intact pollen grains (Fig. 4A). Pollen stored using the custom preparation of 25–75 µm talcum as a carrier demonstrated higher seed set performance than commercial < 75 µm talcum (Supplemental Fig. 7). This team discontinued evaluating the 25–75 µm talcum due to the difficulty of manufacture. Testing crystalline silica in comparison to Florisil® revealed that specific surface area was a critical factor in carrier performance. Crystalline silica particles demonstrated low specific surface area25, <1 m2 g−1, and did not interact with pollen moisture content in this study. Manufacturers engineer Florisil® for high specific surface area26, 298 m2 g−1, which desiccated pollen during storage and resulted in reduced pollen moisture content and low seed set after four days of storage (Supplemental Fig. 7). While scientific literature has not described the specific interaction between Florisil®, relative humidity, and water vapor absorption, amorphous silicas with similar high specific surface areas and pore sizes are well documented27 and are commonly used as desiccants. The breathable barrier technology and crystalline silica were combined into a single protocol and the team was able to preserve pollen viability for up to eight days. This stored pollen delivered a complete seed set (>500 kernels per ear on average for hybrid tester ears) throughout the duration of storage (Supplemental Fig. 8).

A Scanning electron microscopy of stored pollen samples mixed with five carriers. Raw pollen without a carrier is included for reference. B Comparative seed set obtained from pollen stored for five days using five different carriers in equivalent breathable barrier storage vessels. Connecting letters reflect Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05, n = 25 pollinated ears.

While crystalline silica demonstrated excellent performance as a pollen storage carrier, the hazards presented by respirable dust and difficulty in global sourcing challenged the concept of an accessible seven-day pollen storage protocol. The team sourced and tested alternative carriers with the same key properties, including transition metal powders, post-transition metal powders, metal oxides, and metal carbides (Supplemental Table 12). A high seed set was obtained from pollen stored with ferrous metal powders that were expected to be biologically inert. A similar high seed set was obtained from pollen mixed with aluminum oxides28 and titanium29 powders that have been published as non-toxic to plant surfaces when applied as nanoparticles. Powders of metals known to be toxic to plants including nickel30 and tungsten31 were toxic to pollen during storage. Interestingly, cobalt32 has been published as specifically detrimental to pollen tube growth and this negative interaction was confirmed when cobalt powder proved toxic to maize pollen in storage. The high toxicity of zinc oxide powder was not expected. Further study is required to understand why this toxicity does not align with other studies on zinc oxide nanoparticles applied to plant tissue33,34. The lack of toxicity from chromium30 powder was an unexpected result and was hypothesized to reflect the poor solubility of the metal powder that prevented interaction with the pollen.

The team then evaluated microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) as a pollen storage carrier. MCC demonstrates a favorable particle size distribution with a reduced fraction of respirable dust35 and has a low specific surface area36 like that of crystalline silica at approximately 1 m2 g−1. MCC has an intermediate water absorption capacity in a saturated water vapor environment, 21.8% for Avicel® PH-10137, which is less than the published 35–100% water absorption capacity for silica gels27. SEM imaging then demonstrated that MCC does not excessively coat intact pollen grains (Fig. 4A). Test pollination demonstrated that pollen stored with MCC can produce a high seed set (Fig. 4B). Pollen samples stored with Avicel® PH-101, Avicel® PH-102, or Avicel® PH-200 all showed similar performance, suggesting that diverse preparations of MCC are efficacious (Fig. 4B). The team observed that samples stored with Avicel® PH-200 showed reduced flowability during handling, likely due to the large average particle size (manufacturer labeled 167 µm). Avicel® PH-101 (42 µm) demonstrated the best flowability during handling. A pollen dilution experiment using Avicel® PH-101 determined that pollen-to-carrier ratios of 1:2 by volume delivered the highest seed set using the least amount of pollen per ear (Supplemental Fig. 9). Pollen-to-Avicel® PH-101 ratios of 2:1 and 1:2 by volume also produced an excellent seed set. A significant reduction in the seed set was observed at the 1:10 ratio.

The team conducted a final test of the optimal pollen storage carrier hypothesis by testing whether the presence of carrier compounds on maize silks prior to pollen application inhibited pollination in the same manner that was observed when pollen grains were coated in the carriers prior to pollination (Supplemental Table 13). These results demonstrated that the application of talcum to silks prior to applying fresh pollen without carrier significantly reduced seed set compared to fresh pollen alone. Application of 10 µm silica or Avicel® PH-101 to maize silks prior to fresh pollen application did not have a negative impact on the seed set.

Discussion

This body of work examined 100 years of scientific plant research on maize pollen storage, critically evaluated key technical assumptions behind what does and what does not work, and ultimately produced a high-performing, short-term maize pollen storage protocol that is accessible to diverse global users. The first objective was accomplished by confirming that refrigerated storage temperatures are the most immediate and accessible method to depress the pollen respiration rate. Attempts to further depress the respiration rate of maize pollen to control toxic CO2 accumulation showed technical success but did not overcome scalability limitations. Considering the pollen as a dynamic, breathing organism in tissue culture led to the application of breathable barriers to pollen storage. These barriers simplified the protocol, removed the requirement for CO2 sequestration, and enabled efficient storage of the large pollen volumes required for commercial seed production. Critical evaluation of technical assumptions common to the art of maize pollen storage led the team to question whether talcum was inherently limiting pollination performance. Microcrystalline cellulose (MCC) was identified as the best carrier for maize pollen that enabled maximum pollination performance. MCC delivered both an increased seed count per ear and the consistent size and shape of seed from completely pollinated ears which is critical in hybrid seed production. The team hypothesizes that the water-absorbing capacity of MCC is optimal for use as a carrier in metabolically active maize pollen storage. Future studies could fully characterize this interaction between carrier compounds, storage vessel atmosphere relative humidity, and pollen moisture content throughout the duration of storage.

The team was able to combine these innovations into a protocol that is scalable for use cases throughout maize breeding and seed production. The protocol is accessible to global users operating under varying supply chain and infrastructure limitations. Testing within the project and ongoing global deployment within Syngenta have not identified any maize temperate or tropical heterotic groups that were incompatible with the breathable barrier pollen storage technology. Applying the scaled-up breathable barrier pollen storage technology to commercial seed production will require mechanized pollen collection and mechanized stored pollen application over thousands of maize seed production hectares. The team has identified collection and application efficiency as the key challenges for mechanization moving forward. Maize plants functioning as the male parent in hybrid seed production release 5–10 million pollen grains over the course of up to one week. Production scientists can collect only a small fraction of this pollen in a single machine pass. Machine passes and pollen handling must move quickly to avoid pollen dehydration or heat exposure prior to storage, which further challenges collection efficiency. In order to set seed, mechanized pollen application must efficiently dose the bulk stored pollen into <1 mL quantities and effectively target those pollen doses to the silks of plants acting as the female parent. Any stored pollen that misses the silks during application is a complete loss and will not result in a seed set. Both the collection and application steps must be efficient to ensure that the cost of seed production does not exceed the value of the resulting seed. The team anticipates that continued global expansion, scale-up, and mechanization of this technology will bring new challenges that will be addressed using the same tools and techniques described in this study.

Methods

Pollen collection and manual pollination

Maize plants were grown under greenhouse conditions (16-h day length, 25 °C or 27 °C setpoint days, 21 °C nights, 70% relative humidity, High-Pressure Sodium (HPS) or Light Emitting Diode (LED) supplemental lighting) in Durham, North Carolina in the United States. Pollen was collected by covering the tassels with wax paper pollination bags overnight (Midco Global, Tassel Bags, Large, #404, 17.145 cm × 15.875 cm × 12.065 cm × 39.37 cm). Extruded anthers were removed from tassels prior to bagging in order to minimize the quantity of older, non-viable pollen present in samples. Pollen collection bags were removed in the morning around the time of peak pollen shed and viability (between 0800 h and 1000 h based on environmental conditions and line-specific pollen shed behaviors). For plants grown under field conditions, pollen was collected in bulk by manually shaking tassels with extruded anthers into a wax paper bag or other collection vessels. Pollen collection occurred at the time of peak pollen shed and viability (0730–1200 h based on environmental conditions and line-specific pollen shed behaviors). Pollination data from field trials were collected from locations in Clayton, North Carolina, and Elkhorn, Nebraska in the United States.

For both field- and greenhouse-grown plants, any pollen and anthers collected were bulked together by line and passed through an 850 µm (US 20 mesh) sieve to remove anthers. This sieving step also removed >1 mm insects from field-collected pollen samples. The pollen was then immediately mixed with a carrier compound by weight or volume at an experiment-specific ratio. The pollen and carrier were mixed together by manually shaking the two materials in a large container until a uniform mixture was formed. The resulting pollen and carrier mixture were then placed into an experiment-specific storage vessel and placed into an experiment-specific storage condition. All experiments other than those described in Fig. 2A were stored at 6 °C.

For both greenhouse and field-grown plants, silks used for manual pollination were covered using wax paper ear shoot bags (Midco Global, 5.08 cm × 2.54 cm × 17.78 cm) prior to pollination. Under greenhouse conditions, manual pollinations were conducted on detasseled plants with no active shedding, uncovered tassels present within two meters. Under field conditions, manual pollinations were conducted on plants within detasseled plots with no actively shedding tassels present within ten meters. The person conducting pollinations would remove the ear shoot bags and trim silks to between three and six centimeters in length using sharp scissors (Fiskars RazorEdge) immediately prior to stored pollen application. For each pollination described in these experiments, 0.5 mL of pollen and carrier mix was scooped from a bulked sample and evenly distributed across the silks. Pollinated ears were then covered with wax paper pollination bags (Midco Global, Tassel Bags, Large, #404, 17.145 cm × 15.875 cm × 12.065 cm × 39.37 cm). Bags were stapled shut around the plant stalk to avoid outside pollen contamination. Negative check pollinations were conducted by performing the same steps described above where the 0.5 mL of pollen and carrier mix was replaced by a 0.5 mL sample of the pure carrier compound (talcum, crystalline silica, or Avicel® PH-101). Sampling spoons were cleaned with alcohol swabs between use for measuring pollen with carrier mix and use for measuring pure carrier negative checks. For field trialing, open-pollinated check ears were designated by flagging representative plants in the field during ear shoot bagging prior to the start of the pollen shed. These representative plants were marked with row bands or flags on the internode above the primary ear and the ears were not bagged at any point in the season. Pollination data was collected by manually harvesting ears 14–28 days after pollination based on environmental conditions and line-specific development. Manual pollinations, negative checks, and open-pollinated checks were scored by manually counting all the kernels present on each ear. Ears were imaged in batches according to treatment groups or individually imaged prior to manual counting.

Syngenta maize pollen tube germination media and pollen tube germination scoring

Syngenta maize pollen tube germination media is a solid agarose-based media consisting of 100 g L−1 sucrose, 30 g L−1 agarose, 0.37 g L−1 potassium chloride, 0.1 g L−1 boric acid, 0.55 g L−1 calcium chloride, and 0.25 g L−1 magnesium sulfate heptahydrate. Media was adjusted to pH 6.6 prior to autoclaving and was poured into standard 100 mm×15 mm petri plates after autoclave sterilization. Where possible, media plates were left unwrapped overnight to reduce media surface condensation. Excessive media surface condensation was observed to increase pollen grain bursting prior to pollen tube germination. Maize pollen was evenly applied to the media by hand using the same techniques that were used to disperse pollen samples across silks during plant pollination. Pollen was incubated on media plates with the lids closed for a minimum of 60 min prior to imaging for data collection. Plates were kept out of direct sunlight and away from heat sources during incubation. Plates were not wrapped or sealed during incubation. Plates were incubated under a range of temperature (22–35 °C) and relative humidity (15 to >80%) conditions based on the laboratory, greenhouse, or field location where work was conducted. During field pollen collection and application, plates were incubated for between one and 24 h depending on how long it took to return the samples to a location with a microscope. Following incubation, pollen tube germination plates were imaged at 40x magnification. Imaging was conducted using an AmScope™ 40×–2500× Compound LED Microscope equipped with an 18-megapixel camera. Representative images with a minimum of twenty pollen grains per image were collected for each sample. Due to the variability in media handling, incubation, and imaging conditions, the exact count of germinated pollen tubes vs ungerminated or burst pollen grains was difficult to consistently quantify across experiments. In response, the team scored pollen tube germination using an ordinal categorical rating scale. Pollen tube germination was rated by reviewing images and assigning a rating on a 1–5 scale (5 = >≈60% pollen tube germination, 4 = ≈41–60%, 3 = ≈21–40%, 2 = ≈1–20%, 1 = 0% or completely dead and burst pollen). The top rating of “5” covered a larger range of pollen tube germination due to the reduced maximum potential pollen tube germination rates observed under greenhouse conditions. Fresh pollen samples collected under greenhouse conditions rarely exceeded 80% pollen tube germination compared to field-collected samples that showed nearly 100% germination. The team hypothesized that this reduced maximum potential pollen tube germination rate under greenhouse conditions was due to accelerated pollen desiccation. Accelerated desiccation was caused by the high rate of air recycling and the use of conditioned, 70% relative humidity air under greenhouse conditions.

Pollen storage temperature regulation

Extech® SD700 data loggers were used to monitor the ambient temperature, relative humidity, and atmospheric pressure within both the pollen processing (greenhouse, field, and lab) and storage environments (refrigerators and incubators). Pollen stored at 6 °C was kept on wire shelving in a Percival™ I-36NL chamber or on wire shelving in a Fisherbrand™ Isotemp™ Undercounter BOD Refrigerated Incubator. Pollen stored at 2 °C was kept on wire shelving in a Fisherbrand™ Isotemp™ Undercounter BOD Refrigerated Incubator. Pollen stored at room temperature was left on a lab bench out of direct sunlight and away from lab equipment heat sinks. Pollen samples were transported between storage incubators and field trials using a Whynter FMC-350XP 34-quart Compact Portable Refrigerator. Experiments conducted at global field locations used locally available commercial or consumer-grade refrigerators set to hold 6 °C.

Storage atmosphere gas sampling

A Quantek Instruments 902D Bench-top Oxygen & Carbon Dioxide Analyzer was used to measure endpoint oxygen (O2) and carbon dioxide (CO2) content within pollen storage vessels. A Quantek Instruments 902P Bench-top Oxygen & Carbon Dioxide Analyzer or an Ocean Optics NeoFox-GT phase fluorimeter equipped with a BIFBORO-1000-2 FOSPOR-R in-situ optical probe was used for continuous storage vessel atmosphere monitoring. For any given experiment, the same instrument was used to record all reported data points. Sealed pollen storage vessel air pressure was equilibrated to standard atmospheric pressure for endpoint gas sample measurements. These included vessels stored at a vacuum (40 kPa absolute) or vessels that had naturally formed a vacuum due to CO2 sequestration agents (up to −20 kPa gauge). For these samples, pure nitrogen (N2) gas was injected into the storage vessel to adjust atmospheric pressure to 100.3 kPa prior to gas sampling. Gas sample readings were normalized to account for endpoint storage vessel atmospheric pressure, N2 injection, and environmental conditions. Breathable barrier storage vessels remained equilibrated with exterior atmospheric pressure and did not require nitrogen injection. Gas composition data collected from breathable barrier storage vessels were not normalized for reporting.

Linking pollen respiration dynamics to temperature

Pollen samples were collected from maize inbreds grown under greenhouse conditions. Pollen was mixed with talcum at a ratio of two parts pollen, and one part talcum by weight. Samples of the pollen and talcum mixture were measured out by weight and distributed into 125 mL, 485 mL, or 900 mL Ball® Mason Jars (US 4 oz, 16 oz, and 32 oz, respectively). FoodSaver® vacuum containers were tested as pollen storage vessels for vacuum storage and are pictured in Fig. 1C and Supplemental Fig. 3A. Gas analysis and seed set data from FoodSaver® containers are not included in this study due to issues with vacuum leakage during storage. For all sealed storage vessel and vacuum storage experiments, samples of pollen and carrier mix were placed onto an aluminum foil weigh boat or folded square of aluminum foil before being placed into the storage vessel. The aluminum foil was used to avoid the pollen directly contacting any water droplets that may condense on the interior wall of the storage vessel.

Evaluating metabolic gas exchange and storage vessel requirements

Vacuum storage and sealed storage vessel atmospheric modification were accomplished by drilling or punching 10 mm holes into Ball® Mason Jar lids and installing a BD Vacutainer™ Serum Blood Collection Tube (Model 366668) vial septum. For vacuum storage, a BD PrecisionGlide™ 23-gauge × 0.75-inch needle attached to a vacuum line was inserted through the septum alongside a separate, identical needle mounted directly to a vacuum gauge. The whole air from the storage vessel atmosphere was withdrawn using the vacuum line until the target gauge pressure was reached. The same gauge and needle configuration were used to measure endpoint storage vessel atmospheric pressure. For experiments in which O2 or CO2 were enriched within sealed storage vessels, the same protocol described above was used to remove a targeted portion of whole atmospheric air from within the storage vessel. Pure O2 or pure CO2 was then injected from a pressurized tank into the storage vessel until the target storage vessel’s atmosphere pressure and composition were reached.

Evaluating metabolic gas exchange and storage vessel requirements

Carbon dioxide sequestration technologies were selected based on accessibility, minimal technical complexity, and user safety. Active CO2 scrubbing technologies based on pumped air passing through molecular sieves or amine gas treatment were excluded from testing based on high cost and high technical complexity. Biological CO2 scrubbing using algae or similar photosynthetic organisms was excluded due to high technical complexity and lack of scalability. Continuous or intermittent injection of pure O2, N2, or other gas mixtures to dilute the accumulated carbon dioxide were excluded based on high technical complexity and the safety risk posed by compressed gasses. Carbon dioxide sequestration agents were selected for testing based on their ability to work in a sealed storage vessel without electricity, active air movement, and interaction with an operator.

Carbon dioxide sequestration was accomplished using Supleco® soda lime with an indicator (Ca(OH)2 + NaOH)—Sigma Aldrich® (1.06733.0501), lithium hydroxide (LiOH)—Sigma Aldrich® (442410), ethanolamine (C2H7NO)—Sigma Aldrich® (15014), <200 mesh (<75 µm), and 100–200 mesh (75–150 µm) preparations of Florisil® (MgSiO3)—Sigma Aldrich®, Zeolite 3A—Sigma Aldrich® (MX1583D-1 Supelco®), and 100 mesh activated charcoal—Sigma Aldrich® (242276 Darco®). Ethanolamine was aliquoted into pollen storage vessels as a liquid by volume from a stock solution while the other five carbon dioxide sequestration agents were added by weight as a powder or granule. All carbon dioxide sequestration agents were placed into plastic weigh boats within the storage vessel to avoid reactivity with metal surfaces.

Storage vessel pressurization was accomplished using a LACO Technologies LBC1010-100 helium bombing chamber. The chamber was modified to include 0.01-inch (0.254 mm) flow control orifices plumbed into both the air inlet and outlet lines between the respective ball valves and chamber interior in order to avoid rapid pressurization and depressurization. The chamber outlet line was used for vessel headspace atmosphere gas sampling. The chamber was electrically grounded during use to avoid static buildup. For most experiments, the interior volume of the chamber was reduced by partially filling the chamber with freezer gel packs. This use of an incompressible liquid sealed in plastic reduced the ratio of pollen amount to storage vessel atmosphere volume. This enabled experiments to be conducted at a targeted pollen quantity to storage vessel atmospheric volume ratio without the need for collecting >100 mL of pollen for every experiment. Pollen samples and soda lime were added to the chamber in separate trays or weigh boats prior to sealing the chamber shut. Compressed whole atmospheric air was fed into the chamber at 827 kPa (US 120 PSI) using a standard piston air compressor. The gas composition of the compressed air was not modified. The compressed air was not dried with a desiccant prior to use. Reported data reflects a series of experiments using multiple pollen donors and tester ears in greenhouse and field conditions. Average seed sets are not directly comparable.

Evaluation and optimization of breathable barrier technology

Breathable barriers tested in this study included Tyvek® film and cellulose-based 3 M™ Micropore™ Surgical Paper Tape—Fisher Scientific™. Open perforations were tested by drilling or punching holes in pollen storage vessels at an experiment-defined size. The water vapor transmission rate was measured by weight loss of steady state water vapor flow over a unit time over a unit area of the breathable barriers under specific temperature and humidity conditions. The measure of water vapor transmission rates was conducted at 23 °C and 58–61% relative humidity following similar approaches denoted in ASTM Standard Test Methods for Water Vapor Transmission of Materials38. An approximately four-liter Terra Universal model 5235-01B acrylic vacuum chamber with an internal dimensional size of 28 cm × 28 cm × 12.7 cm was placed into a Fisher Scientific™ Incubator Model 6500 chamber. A glycerol water solution was prepared at 80% weight of pure glycerol to deionized water. The specific gravity of the glycerol water solution was 1.4374. Five hundred milliliters of this glycerol water solution were placed into an 8.89 cm by 15.24 cm open container. The open container of glycerol water solution was placed into the acrylic chamber to provide the appropriate humidity within the chamber. Twelve 125 mL Ball® Mason Jars (US 4 oz) with lids were modified to include 71.3 mm2 perforations using a handheld die press. Disks of Tyvek® were taped over the 3.175 mm perforations on three of the twelve lids. An impermeable plate seal film (Linbro Cat No. 76-402-05 MP Biomedicals™, LLC.) was applied to the outer perimeter of the Tyvek® to seal the Tyvek® to the container lid. Micropore™ tape was placed over the perforation on three of the twelve lids. Perforations on the remaining six of the twelve lids were left uncovered. Approximately 60 mL of deionized water was placed into each of the twelve 125 mL Ball® mason jars. Lids were placed onto identical mason jars containing deionized water and sealed using mason jar lid bands. All twelve sealed jars were inserted into the acrylic chamber and the acrylic chamber was placed into a Fisherbrand™ Isotemp™ Undercounter BOD Refrigerated Incubator on wire shelving to maintain a controlled atmosphere for up to eight days. Loss of weight measurements were collected to calculate the water vapor transmission rates from all twelve jars covering the three breathable barrier treatments.

The minimum breathable barrier surface area required to preserve a given quantity of pollen was calculated by preparing a series of 125 mL Ball® Mason Jars (US 4 oz) and modifying the lids to include a single 0.015 mm2, 0.079 mm2, 0.268 mm2, 0.552 mm2, 2.0 mm2, or 7.9 mm2 circular hole. Each vessel was filled with a pollen and talcum mixture equivalent to 2.67 grams of pure pollen per vessel. A small quantity of soda lime was added to each storage vessel. The storage vessels were then sealed by covering the single hole in each lid with Tyvek®. Storage vessels were held at 6° C for five days prior to endpoint data collection.

The dependency of breathable barrier gas exchange in the internal headspace within pollen storage vessels was determined by preparing a series of modified GA7 plant tissue culture Magenta™ boxes. Boxes were filled with varying quantities of Naked Fusion epoxy resin that reduced the 400 mL volume of a stock GA7 box down to 300 mL, 200 mL, or 100 mL. The stock and modified storage vessels shared a common breathable membrane surface area of 42 mm2 based on the perimeter gap between the box body and lid. Over the course of several experiments, a quantity of pollen mixed with crystalline silica and a separate quantity of soda lime was added to each storage vessel. The quantity of pure pollen added to each storage vessel was recorded. The storage vessels were sealed by the perimeter gap below the lid with cellulose tape. Storage vessels were held at 6 °C for five days prior to endpoint data collection.

One-liter scale pollen storage was accomplished using 850 mL VWR® brand cell culture flasks (VWR® Catalog Number 10062-884 or 10062-886). The flasks tested had an internal volume of 1350 mL as measured by water displacement and a vessel mouth opening diameter of 29 mm. Flasks used during pollen storage testing included both the solid cap configuration and flasks equipped with a vented cap containing six holes backed by a 0.22 µm hydrophobic filter. In the stock configuration, one liter of maize pollen mixed with crystalline silica was added to the flask. The flask was sealed by covering the open vessel mouth with a single layer of cellulose tape. For the optimized flask configuration, twenty-two 10 mm holes were drilled at evenly spaced intervals on the top and bottom flat surfaces of the flask such that no portion of the pollen would be greater than 47 mm away from the nearest opening. An additional three 10 mm holes were drilled at evenly spaced intervals into the sides of the cell culture flask to further expand the breathable barrier surface area. This modified configuration is depicted in Supplemental Fig. 5D. These twenty-eight total 10 mm holes combined with the six holes in the vessel cap adjusted the total breathable barrier surface area to 2290 mm2. In the modified configuration, all the added 10 mm holes were covered in cellulose tape, and up to one liter of maize pollen mixed with crystalline silica was added to the flask. The three added holes in each side of the cell culture flask were omitted in later configurations, including the example pictured in Supplemental Fig. 5B. The twenty-two 10 mm holes drilled into the container combined with the six manufacturer-installed holes in the vessel cap modified the total breathable barrier surface area to 1819 mm2.

Evaluation of maize pollen storage carrier compounds

United States Pharmacopeia (USP) standard talcum (3MgO4SiO2H2O) was sourced from Fisher Scientific™ for use as a pollen storage carrier. This product had a particle size of <75 µm and no listed particle size distribution according to manufacturer specifications.

The topography of maize pollen samples mixed with different carriers was observed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Samples were sprinkled onto a carbon adhesive tab attached to an aluminum sample stub. The excess sample was removed by gently tapping the stub while holding it upside down. The samples were then loaded into the SEM chamber and analyzed under variable pressure mode without any conductive coating. All electron micrographs were obtained using a Hitachi SU-3700 (tungsten type) electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 5–10 kV, utilizing an ultra-variable pressure (UVD) detector and a backscatter detector (BS). The vacuum level was set to 150 Pa for all samples pictured.

Compound microscopy of pollen and silk interaction was accomplished using an AmScope™ 40×–1000× microscope equipped with an ultraviolet excitation fluorescence kit. Raw pollen, pollen mixed with talcum, and pollen mixed with <75 µm Florisil® were pollinated onto fresh maize silks in a greenhouse environment. Pollinated silks were collected within 5 min of pollen application for light microscopy imaging. Pollinated silks for aniline blue staining were collected 4 h after pollination to allow sufficient time for pollen tube growth. Silks were softened in 1 M NaOH for 15 min at 90 °C prior to staining. Silks were then removed from the softening solution and placed into an aniline blue staining solution (0.2% Methyl Blue (C32H25N3O9S3Na2) diluted from a 2.5% in 2% acetic acid concentrate, 20 g L−1 K3PO4, pH = 12) for 15 min at room temperature prior to imaging.

Pollen storage carrier compounds including 10 µm crystalline silica (SiO2), 10 µm silicon carbide (SiC), 10 µm 316 L stainless steel powder, 316 L stainless steel powder optimized for 3D printing, 10 µm iron powder (Fe), 10 µm mica, 10 µm zinc oxide (ZnO), 5 µm spherical aluminum oxide (Al2O3), 10 µm spherical aluminum (Al), 10 µm chromium (Cr) powder, 10 µm nickel (Ni), 10 µm titanium (Ti), 10 µm tungsten (W), and 8 µm cobalt (Co) powders were sources from US Research Nanomaterials, Inc. Both 316 L stainless steel powders tested consisted of spherical particles at a specified particle size and differed in the degree of surface polishing. An additional crystalline silica product shown in Fig. 4A was sourced from Viridis Materials (product code 1909-1524-16-284, D10: 2 µm, D50: 15 µm, D90: 42 µm). In all experiments, each of the aforementioned carriers was mixed with fresh pollen at a ratio of two parts pollen, and one part carrier by weight. Pollen storage experiments took place using equivalent pollen storage vessels. This equivalency included using the same quantity of soda lime or the same breathable membrane surface area covered in a single layer of cellulose tape. Avicel® PH-101, Avicel® PH-102, and Avicel® PH-200 microcrystalline cellulose products were sourced through Fisher Scientific™ or Sigma Aldrich®. These carriers were mixed with fresh pollen at a ratio of two parts pollen, and one part carrier by volume. The same batch of pollen, identical pollen storage vessels, and the same cellulose tape breathable barrier were used for direct comparison testing with talcum and 10 µm crystalline silica.

Pollen dilution testing was accomplished by further diluting pollen stored with a carrier. Freshly collected maize pollen was mixed with Avicel® PH-101 microcrystalline cellulose at a ratio of two parts pollen, one part Avicel® PH-101 microcrystalline cellulose by volume. The mixture was placed into a breathable membrane pollen storage vessel and stored for five days at 6 °C. Following storage, subsamples of the bulk 2:1 pollen to Avicel® PH-101 mixture were diluted with additional volumes of Avicel® PH-101 to generate 1:1, 1:2, 1:5, and 1:10 pollen to Avicel® PH-101 ratios by volume. Pollinations for all five ratios were made using 0.5 mL of pollen and Avicel® PH-101 mixture per pollination.

Inhibition of pollination by carrier compounds present on silks was accomplished by pretreating silks with an even coating of carrier compound prior to applying fresh pollen. Standard hand pollination using stored pollen applied 0.5 mL of stored pollen and carrier mix. The 0.5 mL of stored pollen and carrier mix contained 0.33 mL pollen and 0.17 mL carrier based on the 2:1 ratio of the mixture by volume. To replicate these standard volumes and to separate carrier interaction with silks from carrier interaction with pollen, 0.17 mL of a pollen storage carrier compound was evenly applied to the silks on a maize ear. The same ear was then pollinated by evenly applying 0.33 mL of fresh maize pollen. This fresh pollen was not mixed with any carrier compound and was not stored prior to use. This method of carrier pretreatment followed by fresh pollen application was used to test < 75 µm talcum, 10 µm crystalline silica, and Avicel® PH-101. As a positive control, a set of ears was pollinated with 0.33 mL of fresh pollen and did not receive a carrier pretreatment. To test for airborne pollen contamination, a set of ears was pretreated with <75 µm talcum and did not receive any fresh pollen application.

Statistics and reproducibility

The three units of experimental replication present in this study are individual sealed pollen storage vessels (Figs. 2A, B and Supplemental Tables 1–4), individual pollen storage vessels with a breathable barrier (Supplemental Tables 7 and 9), or individual pollinated maize ears (Figs. 3A and 4B and Supplemental Fig. 1 and 7–9, Supplemental Tables 5, 6, 10, 11, 12 and 13). The unit of replication in Supplemental Table 8 is both an individual pollen storage vessel with a breathable barrier and an individual pollinated maize ear (one storage vessel per ear). Data from sealed pollen storage vessels was collected at the endpoint of pollen storage. Vacuum-sealed pollen storage vessels started at −60 Kpa gauge and were rejected from data collection and analysis if the vessel’s internal pressure was above −40 Kpa gauge at the end of storage. Sealed pollen storage vessels that included soda lime were rejected from data collection and analysis if a measurable vacuum was not formed inside the vessel during storage. Both these conditions indicated that the vessel had leaked in exterior air that would introduce supplemental oxygen to the storage environment and would have provided a false assessment of pollen respiration. Individual pollen storage vessels with a breathable barrier naturally equilibrated in air pressure with the external environment and were not excluded on any basis.

Several techniques were used to ensure maize ear pollination experiments were repeatable and led to accurate conclusions. For experiments containing comparisons between multiple treatments (stored pollen samples and silk pretreatments), individual replicates were randomized together by shuffling treatment-specific pollination bags together to create a randomized order. This randomized order ensured that external factors impacting the pollen (heat in the environment, human handling, total handling time, etc.) did not disproportionately affect some treatments over other treatments. For large experiments, shuffled pollination bags were divided between multiple team members conducting pollinations to reduce the overall duration of pollen handling and exposure to environmental stress. When negative check pollinations were included, the pollination bags for these negative checks were randomly shuffled into the stack of experimental treatment pollination bags. Where applicable, open-pollinated ears were selected from representative plants up to one week prior to experimental pollinations. This pre-selection was necessary to prevent the designated open-pollinated ears from being shoot-bagged and blocked from natural pollination. Team members conducting pollinations were experienced maize pollinators and were trained to select representative, normal ears based on what material was available. Only ears that were properly covered with shoot bags prior to the emergence of any silks were used throughout all the experiments in this study. Pollination bags were stapled shut around pollinated ears to minimize contamination by airborne pollen. Individual pollinated maize ears could be the primary or secondary ears of hybrid maize plants or inbred maize plants. Pollinated ears were excluded from data collection and analysis if an external factor not related to the pollination treatment was observed to have impacted the ear. External factors include but are not limited to; plants being damaged by wind, humans, animals, or equipment, and ears being damaged or completely destroyed by corn earworm, corn smut, or other insect and fungal diseases. Pollination data could also be excluded from analysis if the labeled ear bag was lost or destroyed in the field. There were no instances of ear data being excluded due to drought stress or heat stress during or after pollination in the experiments described in this study.

Data visualization and significant difference testing were conducted using JMP® v17.0 and v18.0 (SAS Institute). Significant differences were calculated using Tukey’s Honestly Significant Difference (HSD) test with an α (alpha level) set to 0.05. Tukey’s HSD is a two-sided test.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses