Development of composite electrolyte membranes with functional polymer nanofiber frameworks

Introduction

Organic polymer membranes are considered promising candidates for cost-effective green electrode materials and are expected to meet the rapidly growing energy demand. Proton-conducting polymer electrolyte membranes (PEMs) are effective energy conversion devices that can directly convert the chemical energy of hydrogen and oxygen into electricity and have gained great attention in fuel cell vehicles, stationary power plants, portable devices, and water electrolysis [1,2,3]. Nafion® is a state-of-the-art polymer membrane for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells because of its high proton conductivity and excellent chemical and mechanical stability [4, 5]. However, Nafion® has several drawbacks for next-generation fuel cell vehicles, such as low proton conductivity at temperatures above 100 °C and high oxygen gas crossover, which cause reactive oxygen species (ROS) production.

Recently, the New Energy and Industrial Technology Development Organization (NEDO) of Japan published the “Fuel Cell Technology Development Roadmap for Heavy-Duty Vehicles (HDVs), including buses, trucks, trains, and ships” in March 2023. In the report, NEDO called for significant advances in each of the fuel cell component technologies. To realize the HDVs that will be needed when they become widespread approximately 2030, NEDO has developed a new fuel cell roadmap for HDVs, which sets out target values for each component, such as catalysts, electrolytes, and the gas diffusion layer that makes up the fuel cell stack. Owing to the high power output of fuel cells and the cost-effective performance of HDVs, the PEMs utilized in HDVs are required to be fabricated as thin membranes with a thickness of 8 μm or less and to operate in a higher temperature range at low humidity. In addition, the PEMs are expected to have outstanding durability compared with those used in conventional fuel cell vehicles [6]. As a result, PEMs face the following issues at higher temperatures above 100 °C: (1) The proton conductivity of PEMs drastically decreases at lower humidities because of low water retention above 100 °C. (2) Mechanical strength is insufficient because of the thin membrane thickness of PEMs. (3) Oxygen gas crossover through thin membranes significantly increases, resulting in reduced faradaic efficiency. (4) Achieving long-term fuel cell durability becomes extremely difficult because the chemical degradation of PEMs by ROS is accelerated at high temperatures; higher oxygen gas crossover occurs more rapidly at high temperatures, resulting in large amounts of ROS being generated in PEMs [7]. The target values of the PEMs set by NEDO are summarized in Table 1. As shown in Table 1, the proton conductivity of the PEMs described in the roadmap must be superior to that of the Gore membranes used in the second-generation Toyota MIRAI not only in a wide temperature range of 70 °C to 120 °C but also in a wide humidity range of 30% RH to 80% RH. In addition, the membrane thickness of PEMs must be less than 8 μm to reduce PEM resistance, but at the same time, thin membranes must also achieve excellent membrane durability of more than 50,000 h. The most challenging target value in the roadmap is that the proton conductivity of PEMs must exceed 0.032 (S/cm) at 120 °C and 30% RH. This means that next-generation PEMs require the development of ultrathin polymer electrolyte membranes with high proton conductivity and excellent durability.

On the other hand, the demand for rechargeable secondary batteries has also rapidly increased because of the necessity of sustainable and cost-effective power storage technology or high-energy-demand devices such as electric vehicles [8, 9]. Among various rechargeable batteries, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have been found to be more suitable for next-generation energy storage devices because of their high voltage, high energy density, and fast charge and discharge cycling performance [10,11,12,13]. However, conventional liquid LIBs pose challenges due to safety problems arising from the flammability and chemical instability of the liquid electrolytes, which can lead to fires or short circuits caused by lithium dendrite formation. To solve these issues, much research has been directed toward the development of LIBs with solid-state electrolytes, i.e., all-solid-state LIBs (ASSLIBs), as alternatives to liquid electrolytes [14, 15]. In addition, the use of metallic lithium as an anode provides high potential for the anode to provide significantly enhanced theoretical energy storage capacity. Among various ASSLIBs, solid polymer electrolytes are promising materials compared with solid inorganic electrolytes because of their good flexibility, lightweight nature, excellent processability, thin-membrane formability, and excellent interfacial compatibility with electrodes. Ether-containing polymers such as poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) are the most widely studied materials for solid polymer electrolytes [16]. However, their conductivities drastically decrease at lower temperatures because of the crystallization of the ether structure in the polymer below its melting point. In addition, their lithium transference numbers are extremely low (ca. 0.1 at 60 °C) because of the strong interaction of Li+ with the ether oxygen in the polymer. The mechanical toughness of ether-based polymer electrolyte membranes is also insufficient, and it is difficult to make thin electrolyte membranes. Although Table 1 shows the target values for their practical utilization in polymer electrolyte membranes, their performance still needs improvement.

In this Focus Review, we present new insights into polymer electrolyte membranes where PEMs containing proton-conducting polymer nanofibers significantly increase the conductivity, suppress the oxygen gas crossover, and enable thin membrane fabrication of less than 10 μm by the proton-conducting nanofiber framework and where ASSLIBs containing Li-ion conductive polymer nanofibers drastically increase the conductivity at low temperature, show a high lithium-ion transfer number, and enable thin membrane fabrication of less than 20 μm by the Li ion conductive nanofiber framework.

Composite electrolyte membranes based on proton-conducting polymer nanofiber frameworks

The focus of PEMs for fuel cells is on developing polymer electrolyte membranes that can achieve high proton conductivity not only over a wide temperature range of 70 °C to 120 °C but also over a wide humidity range of 30%RH to 80%RH, low gas crossover between the fuel and oxidant, thin membrane fabrication of less than 10 μm, sufficient thermal and mechanical stability, and long-term durability. Recently, many efforts have been made to develop novel polymer electrolyte membranes based on sulfonated aromatic hydrocarbon polymers because of their excellent chemical and thermal stabilities and good mechanical strength [17]. However, the proton conductivity of these membranes, which contain many sulfonic acid groups to increase the conductivity, is significantly low at high temperatures and low humidity, making it difficult to achieve the target value of NEDO and resulting in a dramatic loss in their mechanical properties due to unfavorable swelling.

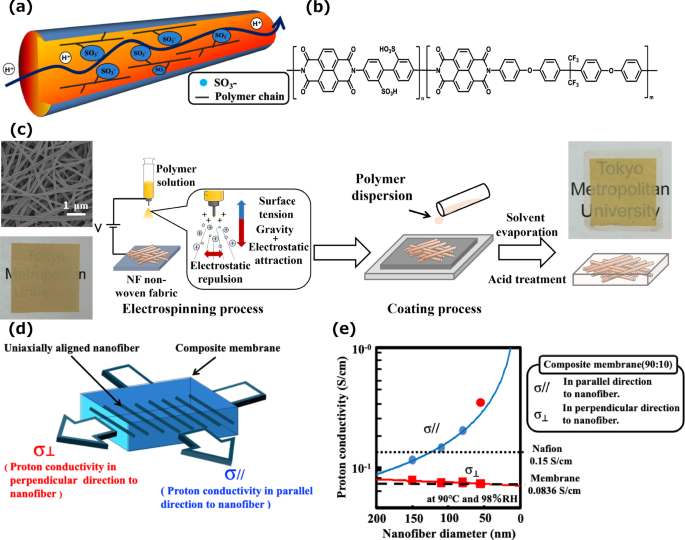

Electrospinning can produce polymer fibers with diameters in the nanometer range, and electrospun polymer nanofibers possess many unique properties, including a large specific surface area, superior mechanical properties, and use as nanoscale building blocks. However, there are only a few reports in the literature on the proton conductivity of electrospun polymer nanofibrous mats for fuel cells [18, 19]. We synthesized the first composite electrolyte membranes composed of sulfonated polyimide nanofibers and sulfonated polyimide for proton exchange membranes (Fig. 1a–c) and revealed dramatically enhanced proton conductivity, low gas permeability, and long durability for the first time (Fig. 1d, e) [20,21,22,23]. In particular, the proton conductivity of the composite membrane containing nanofibers at a low relative humidity of 30% was 10 times greater than that of the membrane without nanofibers. We are the first to prove that protons can be rapidly transported through nanofibers and that nanofibers can not only contribute to the chemical and mechanical stability of the membrane but also facilitate proton transport and inhibit gas permeation through the membrane. Such composite membranes will be promising materials for polymer electrolyte membranes and will be potentially useful for applications in fuel cells. After we proved that composite membranes containing nanofibers are very promising as electrolyte membranes for fuel cells, many researchers began to study the use of nanofibers in polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells. In particular, many studies have investigated the use of nanofibers as reinforcing materials to control membrane swelling [24,25,26,27,28], inhibit gas crossover through the membrane [29,30,31], and improve the mechanical durability of the electrolyte membrane [32,33,34,35,36,37]. In addition, some of these studies propose the possibility of novel composite electrolyte membranes by using carbon nanofibers, sandwich structures with nanofibers, nanofibers coated with polymers, and nanofibers modified with nanoparticles [38,39,40,41]. However, despite this extensive research, the issues of low proton conductivity at high temperature and low humidity still remain.

a Schematic representation of sulfonated polymer nanofibers. b Chemical structure of sulfonated polyimide. c Fabrication method of composite electrolyte membranes composed of sulfonated polyimide nanofibers and sulfonated polyimide. d Direction of proton transport in the membrane. e Proton conductivity of the membranes in parallel and perpendicular directions at 80 °C and 98% RH

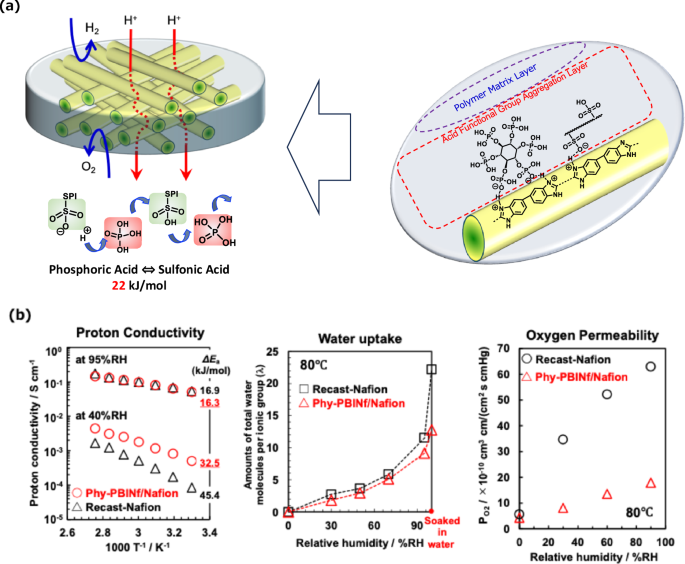

We developed high-performance PEMs based on a nanofiber framework (NfF) to overcome these issues. As shown in Fig. 2a, we designed phytic acid (Phy)-doped polybenzimidazole (PBI) nanofibers (Nf) and prepared composite polymer electrolyte membranes containing Phy-PBI-Nf as NfF, which was filled with typical proton-conducting Nafion® to form dense PEMs [42,43,44]. Phy-PBI-Nf plays multiple important roles in polymer electrolyte membranes, such as NfF: (1) Phy-PBI-Nf provides three-dimensional network nanostructures such as NfF and transports protons and water effectively at the interface between Phy-PBI-Nf as acid-doped nanofibers and the polymer electrolyte matrix. (2) The Phy-PBI-Nf network structures enhanced the durability of the membranes by inhibiting gas diffusion and excessive swelling. As a result, the mechanical toughness of the composite polymer electrolyte membranes containing Phy-PBI-Nf was greatly improved, enabling the fabrication of ultrathin composite membranes with thicknesses less than 5 μm, resulting in significantly lower membrane resistance and subsequent cost reduction. The proton conductivity of the Phy-PBI-Nf composite membrane was clearly twice as high as that of the recast-Nafion membrane, especially at low relative humidity (Fig. 2b). However, the water uptake of the composite membrane was much lower than that of the recast-Nafion membrane at all relative humidities, indicating that the proton conduction in the Phy-PBI-Nf composite membrane was an almost water-independent transport pathway. It is also possible to fabricate ultrathin PEMs in which other polymer electrolyte matrices are introduced instead of the Nafion matrix for future high-performance fuel cells.

a Schematic representation of composite electrolyte membranes composed of phytic acid (Phy)-doped polybenzimidazole (PBI) nanofibers and Nafion. b Proton conductivity, water uptake, and oxygen permeability of composite electrolyte membranes composed of Phy-PBI nanofibers and Nafion

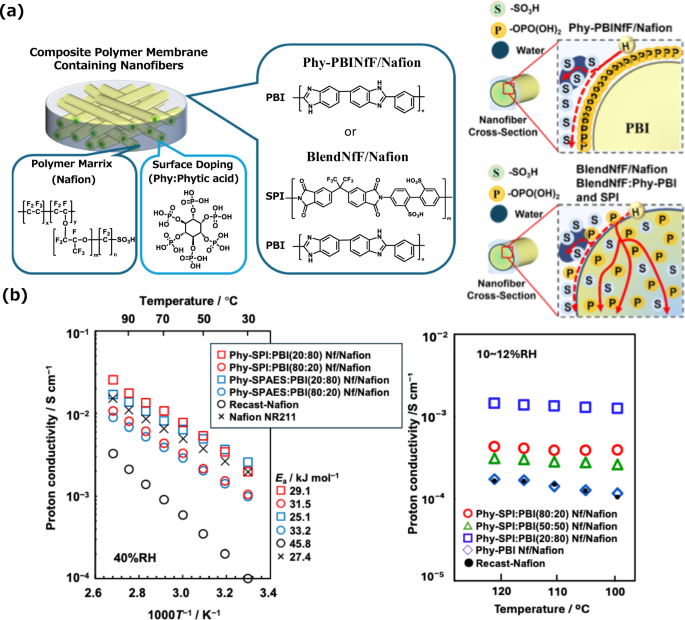

Recently, we reported that composite polymer electrolyte membranes composed of Phy-doped blended polymer nanofibers consisting of sulfonated polyimide (SPI) and polybenzimidazole (PBI) and Nafion possessed high mechanical and chemical stabilities and low gas permeability compared with the Phy-PBI-Nf composite membrane, as shown in Fig. 3a [45]. In addition, the composite membrane containing the blended nanofibers exhibited greater proton conductivity than did the Phy-PBI-Nf composite membrane and the commercial Nafion NR211 membrane, not only at low temperatures but also at high temperatures above 100 °C and 10% RH (Fig. 3b). The proton conductivity of the composite membrane containing the blended nanofibers was strongly dependent on the blend ratio of SPI and PBI, and the composite membranes composed of the blended nanofiber of SPI:PBI (8:2) exhibited much higher proton conductivity than Nafion® at 120 °C and 10% RH due to efficient proton-conducting pathways in the composite membranes, suggesting the potential of the composite membranes containing blended nanofibers for next-generation fuel cells. Proton exchange membrane water electrolyzers (PEMWEs) are currently operated at operating temperatures ranging from 50 °C to 80 °C in water. However, next-generation PEMWEs are expected to work at elevated temperatures above 90 °C due to reduced cell voltages and a reduction in catalyst loading. The composite polymer electrolyte membranes composed of nanofiber frameworks introduced here will be used not only as polymer electrolyte membranes for fuel cells but also as polymer electrolyte membranes for water electrolyzers in the future.

a Schematic representation of composite electrolyte membranes composed of a Phy-PBI nanofiber framework and Nafion (Phy-PBINfF/Nation) or of a blended nanofiber framework prepared from Phy-PBI and sulfonated polimide (SPI) and Nafion (BlendNfF/Nafion). b Proton conductivity of composite electrolyte membranes composed of Phy-PBI nanofibers and Nafion (Phy-PBINf/Nation) or of blended nanofibers prepared from Phy-PBI and sulfonated polymers and Nafion (BlendNf/Nafion). The sulfonated polymers used were sulfonated polyimide (SPI) and sulfonated poly(arylene ether sulfone) (SPAES)

In addition, ion transport by nanofibers is not limited to protons but can also selectively transport anions. Polymer composite membranes composed of anion conductive polymer nanofiber frameworks were also prepared and characterized for future alkaline fuel cells [46]. The anion conductivity of the composite membrane was greater than that of the corresponding membrane, and the membrane stability and mechanical strength of the composite membrane were significantly improved, indicating the potential application of anionic conductive nanofibers in future fuel cells or anion exchange membrane water electrolyzers.

Composite electrolyte membranes based on Li-ion-conducting polymer nanofiber frameworks

The global demand for batteries with high energy requirements, such as electric vehicles and superior energy storage, is increasing worldwide. The use of all-solid-state polymer electrolytes is one of the most promising approaches for realizing Li metal batteries with high voltage, high energy density, fast charge and discharge cycling performance and good safety performance [47, 48]. Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO), which contains an ethylene oxide (EO) unit that can interact with Li+ donor sites, is considered one of the most promising polymer materials for all-solid-state Li-ion batteries (ASSLIBs) [49, 50]. However, conventional PEO-based polymers easily crystallize at temperatures below the melting point, resulting in both low Li+ conductivity and a low transference number at room temperature. In addition, PEO-based polymers suffer from poor mechanical and thermal properties, a narrow electrochemical window (less than 4.0 V), and rapid growth of dendrites [51, 52]. Moreover, several other polymer electrolytes, including polyacrylonitrile (PAN), polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF), polyvinylcarbonate (PVCA), and polyethyl α-cyanoacrylate (PEVA), have garnered significant interest [53,54,55]. However, the Li+ conductivity of the reported polymer electrolytes still cannot reach 1.0×10−3 S cm−1 at room temperature, which is not sufficient for preferable battery performance.

Using reinforcements for polymer electrolyte membranes is an effective way to overcome these issues. Among various reinforcements, polymer nanofibers have attracted significant attention as promising materials for improving poor mechanical and thermal properties [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64], enabling the fabrication of thinner membranes [65], and inhibiting polymer crystallization [66]. The nanofibers for polymer electrolyte membranes should have the following characteristics: (1) sufficient strength for preparing thinner membranes and thermal stability, (2) high porosity for filling polymer materials without interrupting Li+ diffusion between nanofibers, and (3) the suppression of Li dendrite growth. However, the battery performance of polymer electrolyte membranes, even those with nanofibers, still needs improvement in terms of their low Li+ conductivity and transference number before they can be used practically.

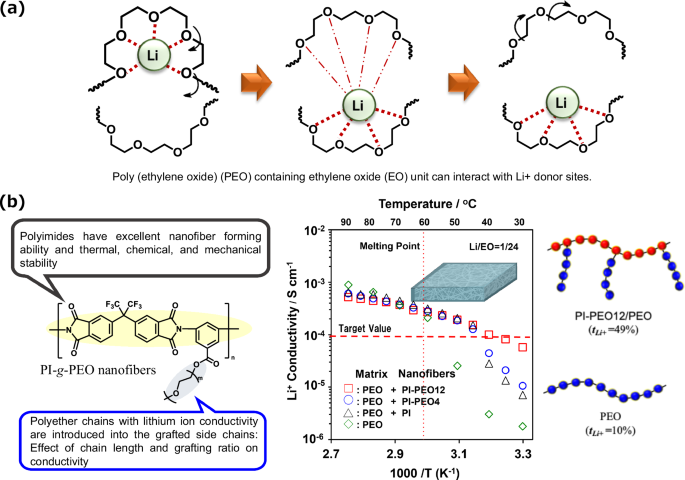

We suggest new structural polymer electrolyte membranes consisting of a Li+ conductive nanofiber framework and a polymer electrolyte matrix, namely, PEO, as shown in Fig. 4a [67]. The Li+-conductive nanofiber framework was designed using short PEO chain-grafted polyimide (PI-g-PEO) nanofibers (Fig. 4b). Compared with PEO electrolyte membranes without nanofibers, polymer composite electrolyte membranes composed of PI-g-PEO nanofibers and a PEO matrix demonstrated enhanced Li+ conductivity, and the Li-ion conductivity of the former at 40 °C was approximately 100 times greater than that of the latter. However, the ion conductivities include not only Li+ conductivity but also anion conductivity for Li ions. Therefore, the Li+ transference number (tLi+) is an important factor for the ion conductive characteristics of polymer electrolyte membranes. Although the tLi+ of the PEO electrolyte membrane was 0.10, the composite membrane containing PI-g-PEO nanofibers had a significantly greater value (tLi+ = 0.49) than did the PEO membrane without nanofibers. In other words, the polymer electrolyte membranes containing PI-g-PEO nanofibers demonstrated not only excellent mechanical and thermal stability but also remarkably high Li+ conductivity and a high transference number because of the effect of the nanofiber framework, which contributed to the significant battery performance in terms of good charge‒discharge cycling behavior.

Schematic representation of a the interaction between the ethylene oxide (EO) of poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) and Li+ donor sites and b of polymer composite electrolyte membranes composed of PI-g-PEO nanofibers and a PEO matrix

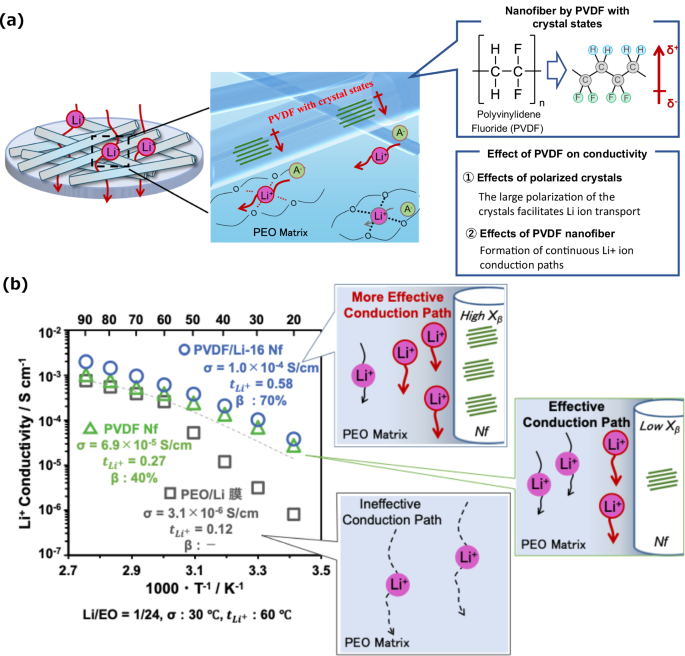

More recently, we prepared novel polymer electrolyte membranes based on crystalline polymer nanofibers consisting of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) and reported improved Li+ conductivity and transference number, as shown in Fig. 5a [68]. Research has revealed that the electrolyte characteristics of polymer electrolyte membranes are influenced by the crystal state and degree of crystallinity of the PVDF nanofibers. Interestingly, the polymer electrolyte membranes containing PVDF with higher β-phase crystallinity presented increased Li+ conductivity (σ = 6.0 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 60 °C) and a greater Li+ transference number (tLi+ = 0.58 at 60 °C). These results indicated that the β-phase crystals in the high-polarity PVDF nanofibers enhanced the Li+ mobility within the PEO matrix (Fig. 5b). In addition, the composite membrane containing PVDF had a greater maximum stress (5.3 MPa) and a lower degree of elongation (71.6%) than did the PEO membrane without nanofibers (0.53 MPa and 383%, respectively). The elastic modulus (Young’s modulus) of the composite membrane was 67 MPa, which was much greater than that of the PEO membrane without nanofibers (12 MPa), since the rigid three-dimensional frameworks formed by the PVDF nanofibers possessed outstanding mechanical properties and suitable mechanical characteristics. Moreover, the polymer electrolyte membranes also suppressed the formation of Li dendrites during battery operation for a long time because of the improved mechanical strength provided by the nanofiber frameworks. A multistacked battery using the ASSLIB with nanofiber frameworks was also successfully demonstrated for future high-voltage batteries (17.0 V).

a Schematic representation of the Li-ion conductivity of polymer composite electrolyte membranes composed of PVDF nanofibers and a PEO matrix. b Effect of PVDF nanofibers on Li-ion conductivity in polymer composite electrolyte membranes composed of PVDF nanofibers and a PEO matrix

Summary and perspective

Electrospun polymer nanofibers are very promising structural materials for use as frameworks in fuel cells and ASSLIBs because of their outstanding mechanical and thermal stability, excellent structural stability, which enables thinner membranes, and uniform porosity. In recent years, nanofibers have greatly contributed to the improved performance of fuel cells and ASSLIBs, such as enhanced ion conductivity, long-term durability, and thinner membrane formation. In this focus review, we extensively discuss recent advances in polymer nanofiber frameworks in electrolyte membranes. First, the development of next-generation PEMs for fuel cells that can achieve high proton conductivity not only across a wide temperature range of 70 °C to 120 °C but also across a wide humidity range of 30%RH to 80%RH, low gas crossover between the fuel and oxidant, thin membrane fabrication of less than 10 μm, sufficient thermal and mechanical stability, and long-term durability is reviewed. Despite the increasing success of various materials demonstrating the great potential of PEMs, there are still challenges and opportunities in this field that have not been fully explored: (1) high proton conductivity at high temperatures above 100 °C and low relative humidity (ca. 30% RH), (2) thin membrane fabrication of less than 10 μm, and (3) PEM durability of 50,000 h. To overcome these issues associated with current PEMs, the development of functionalized polymer nanofibers, organic‒inorganic hybrid nanofibers, and blended polymer nanofibers has received much attention. These nanofibers can form proton transfer channels at the nanofiber surface or within to improve PEM performance, and the design, modification, and optimization of their nanofibers can provide a promising route for thinner membrane fabrication and long-term durability in PEMs. Various polymer nanofibers will undoubtedly play a significant role in providing theoretical and practical insights into the development of next-generation PEMs.

Furthermore, polymer nanofibers are promising candidates for achieving high voltage, high energy density, fast charge and discharge cycling performance and good safety performance in ASSLIBs. The unique characteristics of polymer nanofiber materials have been summarized, and various nanofibers designed for optimizing and improving polymer electrolyte membranes have been highlighted. Although the results from the current use of polymer electrolyte membranes containing nanofibers are promising, critical issues remain hindering their practical application in next-generation ASSLIBs. In particular, the poor Li+ conductivity and transference number at room temperature remain serious problems. To solve these problems, nanofibers must have ion transport pathways that increase ion conductivity by interacting with the polymer matrix or by using their surface or interior in the electrolyte membrane. In addition, the development of thinner polymer electrolyte membranes with good mechanical strength and high ion conductivity is also very important for the development of high-performance batteries with high gravimetric and volumetric energy densities. Furthermore, thinner polymer electrolyte membranes can contribute to cost reduction. Nanofiber-based polymer electrolyte membranes are considered among the next-generation energy storage devices with high capacity and excellent cycling stability. Future nanofiber technological advances will lead to the development of innovative polymer electrolyte membranes with high ionic conductivity and superior mechanical and thermal properties. Composite ASSLIBs prepared using a polymer nanofiber framework are an essential development direction because of their preferable battery performance. Nevertheless, the formation of a solid-state electrolyte interface (SEI) layer between the polymer electrolyte membrane and the lithium metal anode, which reduces battery performance, is challenging [69,70,71,72]. However, the era of thinner, high-performance polymer electrolyte membranes composed of high-performance polymer nanofiber frameworks is about to emerge.

Responses