Development of deformable and adhesive biocompatible polymer hydrogels by a simple one-pot method using ADIP as a cationic radical initiator

Introduction

Polymer hydrogels consist of chemically or physically crosslinked polymer networks that swell in aqueous media. They exhibit unique properties, such as flexibility and mass transport between the gel phase and the external phase, and can be applied as biomaterials [1,2,3]. Recently, adhesive hydrogels have received immense research interest in environmental applications, such as underwater adhesion [4,5,6], and in futuristic applications, such as wearable bioelectronics and soft robotics [7,8,9]; however, the ability to control hydrogel deformability is important for these applications. Several studies have reported methods for controlling the network structure and chemical reactions, which are critical for hydrogel applications [10,11,12,13]. To achieve adhesive properties in hydrogels, various strategies, including mussel-inspired chemistry, cation‒π interactions, copolymerization of zwitterionic and ionic monomers, swelling property control, viscoelasticity control, and the introduction of stimuli-responsive grafted chains, have been investigated [14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. However, there has been limited progress in the development of highly deformable, adhesive hydrogels because the complex factors underlying the fundamental control mechanism are not yet fully understood. Therefore, it is necessary to further elucidate these mechanisms and develop a simple and rational strategy to fabricate highly deformable, adhesive hydrogels.

Free radical polymerization (FRP) using a chemical crosslinker is one of the most versatile methods for preparing functional hydrogels because of the diversity of available monomers. In general, owing to the characteristics of FRP, the resulting polymer gel network is inhomogeneous [21,22,23], which makes it difficult to precisely tailor the gel properties. Thus, the effects of the radical polymerization reactivity or reaction conditions on the network structure must first be understood. Recently, tough hydrogels were fabricated using conventional FRP with a high monomer concentration and low chemical cross-linker content; this allowed the introduction of several entanglements as physical crosslinking points [24]. Furthermore, the monomer sequence in the gel network, which can be controlled by monomer reactivity, plays an important role in the design of functional hydrogels. For example, Ida et al. reported that the formation of a local hydrophilic–hydrophobic–hydrophilic sequence without a long sequence of hydrophobic monomers is required to obtain thermoresponsive gels with sharp transition behavior [25]. Fan et al. developed adhesive hydrogels composed of adjacent cationic–aromatic monomer sequences via cation–π complex-aided FRP [26].

To rationally design viscoelastic, deformable, and adhesive hydrogels, the factors affecting these properties must be investigated from the viewpoint of FRP reactivity. It is generally assumed that the reactivity of the chemical crosslinker affects the mechanical properties of the resulting hydrogels; however, this relationship has not been considered to date in hydrogel design. Furthermore, monomer reactivity during copolymerization can be investigated by altering the monomer/crosslinker combination. In addition, we focused on the radical initiator, whose reactivity affects the gel network and the resulting functionality. Recently, a cationic initiator, 2,2′-azobis-[2-(1,3-dimethyl-4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-3-ium-2-yl)]propane triflate (ADIP) (chemical structure shown in Fig. 1a), was developed, and this compound has received attention in the design of functional soft materials [27,28,29,30,31]. We previously discovered that a thermoresponsive hydrogel prepared with ADIP exhibits a faster volume transition than hydrogels prepared with a conventional azo-type radical initiator, indicating that the reactivity of the initiator affects the network structure [30]. The results further indicated that the radical initiator also plays an important role in controlling hydrogel properties.

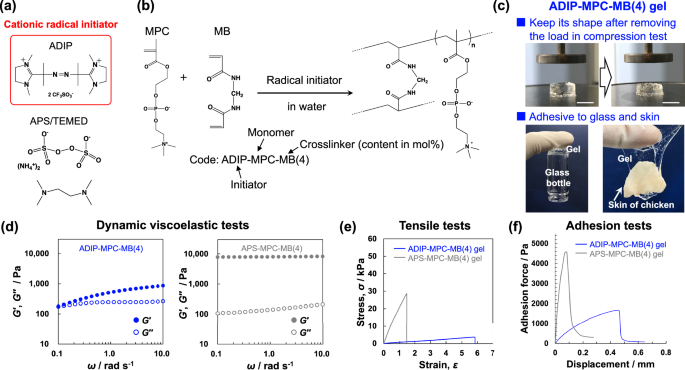

Synthesis and characterizations of the PMPC hydrogels obtained by FRP. a Structure of the radical initiators. b Synthesis of hydrogels by FRP. c Appearance of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel, exhibiting tolerance to compression and adhesiveness. Scale bar in the upper images: 10 mm. d Dynamic viscoelastic tests of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels. Closed and open circles indicate the storage and loss moduli, respectively. e Tensile stress‒strain curves of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels. f Adhesion force curves of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels to a glass substrate

In this study, we report the preparation of highly deformable, adhesive hydrogels composed solely of monomers and a chemical crosslinker (denoted “pure adhesive hydrogels”) using ADIP as a radical initiator. To investigate the role of the radical initiator and to facilitate comparison, hydrogels were also prepared using a conventional redox-type initiator, ammonium persulfate/N,N,N′,N′-tetramethylethylenediamine (APS/TEMED). Considering applications in the field of biomaterials, hydrogels composed of biocompatible 2-methacryloyloxyethyl phosphorylcholine (MPC) were prepared. Furthermore, the mechanism underlying the synthesis of deformable, adhesive hydrogels was elucidated by analyzing the polymerization behavior under different initiator and monomer–crosslinker combinations. In addition, we evaluated the cytocompatibility of the pure adhesive PMPC hydrogel.

Results and discussion

Properties of the PMPC hydrogel prepared with ADIP

First, a chemically crosslinked hydrogel was prepared using ADIP, and the 10-h half-life temperature was calculated to be 35.8 °C, which is suitable for polymerization at 25 °C (Fig. 1b); the Arrhenius plot for the decomposition of ADIP is shown in Fig. S1 in the Supporting Information. Owing to the applications of adhesive hydrogels in biomaterials, MPC was selected as the monomer. These gel samples are referred to as initiator–monomer–crosslinker(X) gels, where X represents the feed content of the chemical crosslinker. For comparison, gel samples were also prepared using APS/TEMED as a conventional water-soluble radical initiator, and polymerization was performed at 25 °C. For both radical initiators, the ratio of radical initiator to monomer was fixed at 1 mol%. We discovered that the PMPC gel prepared with ADIP and N,N′-methylenebisacrylamide (MB) as the crosslinker (4 mol% relative to MPC) (abbreviated as ADIP–MPC–MB(4)) exhibited different mechanical properties from the gel prepared with APS/TEMED as the initiator. First, the compression test was performed. When compressed to 0.95 strain, corresponding to a stress of 300 kPa, the gel maintained its original shape even after the load was removed. In contrast, the PMPC gel with 4 mol% MB crosslinker and APS/TEMED (abbreviated as APS–MPC–MB(4)) fragmented under compression. The stress–strain curves for the compression tests are shown in Fig. S2 in the Supporting Information. Interestingly, the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel adhered to various materials, including glass and skin (Fig. 1c). As quantitative data for skin adhesion, the force‒displacement curves from the peel-off test are shown in Fig. S3 in the Supporting Information. The maximum force of ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel adhesion to skin was ca. 500 Pa. A detailed quantitative discussion of adhesion to a glass substrate is provided below.

Dynamic viscoelastic measurements, tensile tests and adhesive tests were performed to quantitatively characterize the mechanical properties and adhesiveness of the samples. The viscoelastic properties of the as-prepared hydrogels were evaluated by measuring the storage modulus (G′) and loss modulus (G′′) as a function of angular frequency (ω) (Fig. 1d). The loss tangent was determined as tan δ = G′′/G′. The G′ value of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was smaller than 1 kPa. Moreover, the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel exhibited strong viscoelastic properties; the storage modulus decreased as the angular frequency decreased, and the tan δ values were larger than 0.3. Figure 1e shows the stress–strain curves from the tensile tests of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels. Here, the breaking strain in the tensile tests is used as an index of deformability. The breaking strain of the PMPC gel increased by approximately four times when ADIP was used as the radical initiator, and the Young’s modulus decreased to 1.2 kPa. These results indicate that the crosslinking density decreased when ADIP was used as the radical initiator. In a relevant study, Norioka et al. reported the formation of tough hydrogels using FRP with a high monomer concentration and low chemical crosslinker content; such conditions are also applicable for PMPC hydrogels. The Young’s moduli of tough PMPC hydrogels synthesized at monomer concentrations of 2.5, 5, and 10 mol/L with 0.1 mol% crosslinker were 16.6, 60.4, and 74.0 kPa, respectively, and the breaking strain was approximately 3.0 [24]. Compared with these gels, the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel was significantly soft (Young’s modulus: 1.2 kPa) owing to its low monomer concentration but was more deformable; the breaking strength of the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel was twice that of the tough PMPC gels in a previous study.24 In addition, the equilibrium swelling ratios of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels were 51.5 and 12.1, respectively, where the swelling ratio was determined as Ws/Wd (Ws: weight of swollen gel, Wd: weight of dried gel). This was attributed to a decrease in the elastic modulus. The reason for the decrease in crosslinking density when ADIP was used as the radical initiator is discussed in a later section.

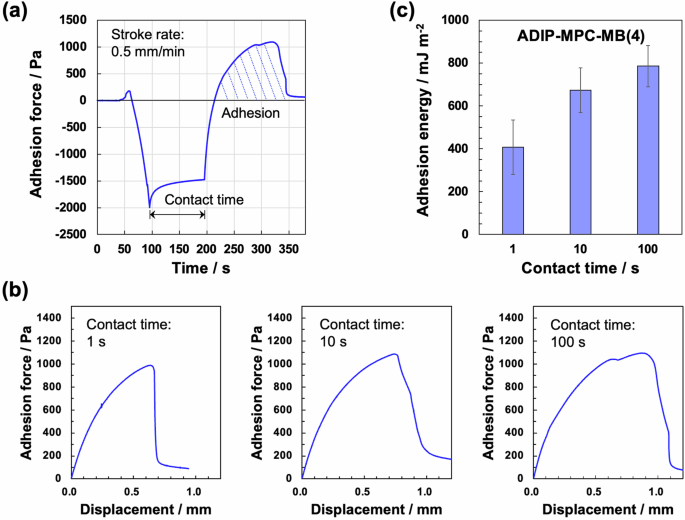

The adhesion properties of the hydrogels were quantitatively investigated using the peel-off test (Fig. 1f). The adhesion forces of the gels on the glass substrate were measured as a function of peeling displacement. Both PMPC gels adhered to the glass substrate via dipole‒dipole or ion‒dipole interactions [16, 32]. Notably, the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was significantly tolerant to peeling displacement. In the design of adhesive materials, the dissipation of adhesive properties is important [33]. The viscoelasticity of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel, as indicated by the large tan δ value, was expected to influence the adhesion properties. To investigate whether this was the case, we performed adhesion tests at various contact times between the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel and glass. Figure 2a shows representative time course data for the adhesion test with a contact time of 100 s. As the contact time increased, the displacement at which the adhesion force reached its maximum also increased. Moreover, after the adhesion force reached its maximum, the decrease in adhesion force became more gradual with increasing contact time (Fig. 2b). Consequently, the adhesion energy, calculated as the area under the adhesion force–displacement curve, increased as the contact time increased (Fig. 2c). This contact time-based adhesion behavior can be attributed to the viscoelastic properties of the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel. Thus, pure adhesive hydrogels, which are highly deformable and adhesive hydrogels composed solely of a monomer and a chemical crosslinker, were produced.

Adhesion behavior of the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel with changing the contact time. a Time course data for the adhesion test for the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel. As representative results, data corresponding to a contact time of 100 s are shown. The stroke rate was fixed at 0.5 mm/min. b Representative adhesion force‒displacement curves at different contact times (1, 10, and 100 s). c Adhesion energy at different contact times (n = 3)

Mechanism underlying the production of deformable and adhesive hydrogels using ADIP

Given that the deformability and adhesive properties of hydrogels are important, we aimed to investigate the mechanism underlying the formation of such “pure adhesive gels.” To clarify the effect of the radical initiator, the polymerization behavior of linear PMPC was investigated using ADIP and APS/TEMED as radical initiators. Table 1 summarizes the characterization results. The monomer conversion was determined using 1H NMR spectroscopy (kinetic plot shown in Fig. S4(a) in the Supporting Information). The polymerization kinetics at 25 °C using ADIP were slower than those using APS/TEMED; however, the monomer conversion reached 92.6% after 24 h of polymerization with ADIP. Regarding the molecular weight of the obtained polymer, the weight-averaged molecular weight (Mw) values when ADIP and APS/TEMED were used as the radical initiator were 3.0 × 105 and 4.0 × 105, respectively (the gel permeation chromatography (GPC) profiles are shown in Fig. S4(b) in the Supporting Information). In addition, the intrinsic viscosity of PMPC synthesized using ADIP was lower than that of PMPC synthesized with APS/TEMED. Thus, the average molecular weight of the polymer synthesized with ADIP was lower than that of the polymer synthesized with APS/TEMED, where the molar ratio of the initiator to the monomer was fixed.

Moreover, the effect of the initiator on the gel content, which is the content of components bound to the gel network, was investigated. The content of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was lower than that of the APS–MPC–MB(4) gel; that is, the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel contained a component that was not connected to the gel network (the sol fraction). This sol fraction in the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel corresponded to a decreased crosslinking density and contributed to its viscoelastic properties. These investigations suggested that ADIP generates polymers with lower molecular weight, resulting in a hydrogel with a lower crosslinking density and a higher sol fraction compared to hydrogels obtained using APS/TEMED. When APS/TEMED was used as the radical initiator, soft and deformable hydrogels were obtained by decreasing the chemical crosslinker (MB) content to below 1 mol% of the monomer (Fig. S5 in the Supporting Information). This suggests that ADIP results in a decrease in crosslinking density, which is suitable for deformability and adhesiveness.

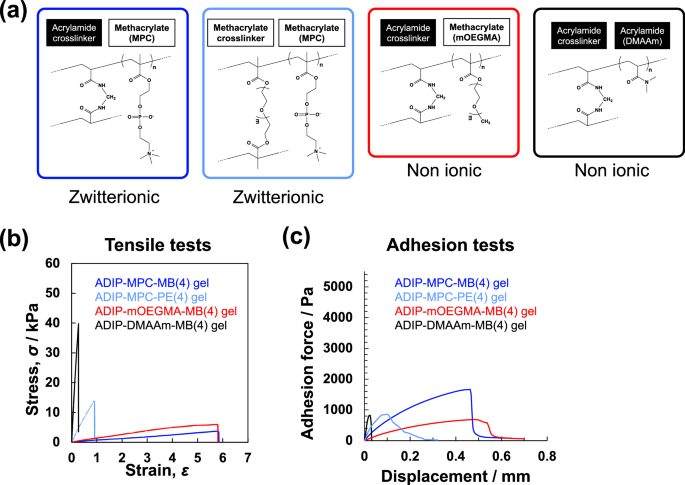

To further clarify the conditions required to generate deformable and adhesive hydrogels using a cationic initiator, we investigated hydrogels prepared with different monomer/crosslinker combinations, given that the combination of monomer skeletons affected the reactivity of the monomers (Fig. 3a). Poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PE), a water-soluble, methacrylate-type chemical crosslinker, was used to compare PMPC gel crosslinked with chemical crosslinkers with different skeletons (acrylamide-type MB or methacrylate-type PE). In addition to the PMPC gel, hydrogels composed of oligo(ethylene glycol) ethyl ether methacrylate (mOEGMA) or N,N-dimethylacrylamide (DMAAm) as hydrophilic methacrylate- and acrylamide-type monomers, respectively, were prepared to compare the effects of the ionic side chain on the resulting hydrogel properties.

Effect of monomer/crosslinker combination on the deformation and adhesion of the hydrogels synthesized with ADIP. a Chemical structure of the hydrogels with different monomer/crosslinker combinations. b Tensile stress‒strain curves of the hydrogels prepared with ADIP. c Adhesion force curves of the hydrogels prepared with ADIP

Figure 3b shows the tensile stress–strain curves of the hydrogels prepared with different monomer/crosslinker combinations. The Young’s modulus (E) was obtained from the initial slope of the stress‒strain curve. The ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and ADIP–mOEGMA–MB(4) hydrogels were significantly more deformable and soft than the ADIP–DMAAm–MB(4) and ADIP–MPC–PE(4) hydrogels. The effect of the monomer/crosslinker combination on adhesion behavior was also evaluated (Fig. 3c). As shown by the adhesion force curves in the peel-off test, the deformable hydrogels ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and ADIP–mOEGMA–MB(4) were adhesive and tolerant to peeling.

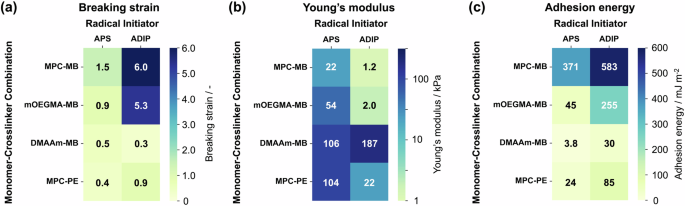

The overall trends of these investigations are summarized in Fig. 4. The hydrogels were also prepared using different monomer/crosslinker combinations using APS/TEMED and were characterized. The tensile stress‒strain curves and adhesion force curves for the hydrogels prepared with APS/TEMED are shown in Fig. S6 in the Supporting Information. Figure 4a and b shows heatmaps of the breaking strain and Young’s modulus of the hydrogels. The Young’s modulus and breaking strain of the hydrogels showed a trade-off relationship, which is common in hydrogel synthesis using a chemical crosslinker. Deformable hydrogels with a combination of methacrylate-type monomers and acrylamide-type crosslinkers could be synthesized by using ADIP as the radical initiator, but not APS/TEMED. These results indicate that the reactivity of the acrylamide-type crosslinker was low for the methacrylate-type monomer and that the ionic properties of the side chains were not affected. Figure 4c shows a heatmap of the adhesion energy, calculated as the area under the stroke–adhesion force curve. Among the hydrogels, APS–MPC–MB(4), ADIP–MPC–MB(4), and ADIP–mOEGMA–MB(4) exhibited the highest adhesion energies. Notably, the adhesion energy of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was the largest among the hydrogel types investigated here owing to the synergistic effect of viscoelastic characteristics and dipole‒dipole or ion‒dipole interactions on the adhesion target. The sample with the second largest adhesion energy was APS–MPC–MB(4), although its breaking strain and Young’s modulus were lower and larger, respectively, than those of ADIP–mOEGMA–MB(4). In addition, its tan δ value was less than 0.1 (Fig. 1d). A comparison of the APS–MPC–MB(4) and ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gels and the APS–MPC–PE(4) and ADIP–MPC–PE(4) gels revealed that the use of MB as the crosslinker was correlated with high adhesion energy. We hypothesized that when MB, which has low reactivity with MPC monomers, is used as the crosslinker, dangling chains are more likely to form on the surface of the hydrogel even if the crosslink density increases, contributing to an increase in adhesion energy.

Summary of the hydrogel properties synthesized under different conditions. Heatmaps of the (a) breaking strain, (b) Young’s modulus, and (c) adhesion energy of the hydrogels with different monomer/crosslinker combinations and two different radical initiators (ADIP or APS/TEMED)

To evaluate the formation mechanism of the pure adhesive hydrogels, considering the reactivity between the monomer and crosslinker, the consumption of the monomer and crosslinker was analyzed by 1H NMR (Fig. S7–S9 in the Supporting Information). Table 2 summarizes the consumption amounts of C = C moieties in the monomer and crosslinker during the crosslinking and chain extension reactions. Here, the consumption was calculated as the ratio of the difference (reduction) in amount to the feed amount of each chemical (monomer or crosslinker). For the crosslinking and chain extension reactions of the acrylamide-type monomers DMAAm and MB, the consumption of MB was greater than that of DMAAm, as indicated by the large reduction in the MB-derived peak (Fig. S7 in the Supporting Information). This result indicates that the acrylamide-type crosslinker MB had higher reactivity and that incorporation of the crosslinker into the polymer chain proceeded faster than the DMAAm polymer chain extension reaction at the initial stage of polymerization. This finding is consistent with a previous report by Baselga et al. [34]. Moreover, when the methacrylate-type compound MPC and mOEGMA were used as monomers, the consumption of the MB crosslinker was lower than that when an acrylamide-type monomer was used (Table 2). On the basis of this analysis, the reaction between the methacrylate monomers and the acrylamide-type MB crosslinker was speculated to proceed as follows: The reaction of the chemical crosslinker with the polymer chain was slower than the polymer chain extension reaction. This resulted in the formation of a hydrogel with few crosslinking points. Thus, this analysis indicates that the combination of a methacrylate-type monomer and the acrylamide-type crosslinker MB is suitable for obtaining pure adhesive hydrogels. From the above investigations, we conclude that the factors promoting the synthesis of pure adhesive hydrogels are as follows: (1) the relatively low molecular weight of the polymer produced with ADIP; and (2) the combination of a methacrylate-type monomer and the acrylamide-type crosslinker MB because the low reactivity of MB to methacrylate-type monomers decreases the crosslinking density and gel content.

Cytocompatibility of the PMPC hydrogel prepared with ADIP

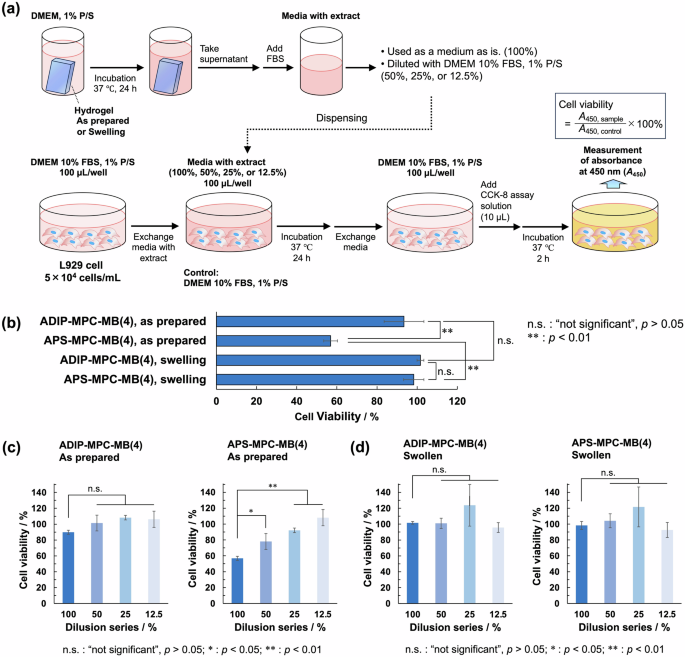

Owing to the skin-adhesive properties (Fig. 1c) of the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel, it has potential as a skin-adhesive biomaterial and in devices; for example, it can be used in wound dressing materials, wearable sensors, and hydrogel patches for drug release. For such applications, it is necessary to evaluate the cytotoxicity of pure adhesive hydrogels. In a previous study, the cytocompatibility of a wearable device was evaluated using extracts as well as a cellular adhesion test. For samples with 100% and 50% extracts, when the cell viability was almost 100%, cells were able to survive, adhere and proliferate when in contact with the actual material. These findings indicate that cell viability tests using extracts are suitable indicators of cytocompatibility [35]. The viability of fibroblast L929 cells cultured in media containing PMPC hydrogel extracts was analyzed (Fig. 5a). Cell culture media containing hydrogel extracts were prepared by immersing as-prepared or swollen hydrogels in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM). A dilution series was prepared by mixing cell culture medium without hydrogel extract. Here, “100%” indicates that culture medium containing hydrogel extract was used at its original concentration. Cell viability was analyzed using a Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay. First, we investigated the as-prepared hydrogels, in which the media containing the hydrogel extracts were considered to contain unreacted chemicals from the radical polymerization process. When the as-prepared ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was tested, cell viability remained unchanged, and the effect of dilution was not significant. (Fig. 5b, c). When the as-prepared APS–MPC–MB(4) gel was used, cell viability decreased depending on the dilution of the extract (Fig. 5c). This result indicated that the cytotoxicity of the hydrogel prepared with ADIP as the radical initiator was low. The cytotoxicity observed for the as-prepared APS–MPC–MB(4) hydrogels can be attributed to the remaining chemicals, such as APS or TEMED. Next, the swollen hydrogels were tested, where the hydrogels were immersed in water for 2 days by changing the external aqueous solution. No decrease in cell viability was observed for the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS-MPC-MB(4) hydrogels, regardless of dilution (Fig. 5b, d). Thus, both swollen gels exhibited low cytotoxicity when unreacted chemicals were removed during the water immersion process. In addition, when L929 cells were cultured with swollen ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel, cellular adhesion and proliferation were observed (Fig. S10 in the Supporting Information). This result also indicated the cytocompatibility of the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel. Overall, the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) hydrogel was highly deformable, adhesive, and cytocompatible. Additionally, hydrogels containing bovine serum albumin (BSA) were immersed in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) solution containing BSA. The concentration of BSA incorporated into the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was higher than that incorporated into the APS–MPC–MB(4) gel (Fig. S10 in the Supporting Information). This is because the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel had a larger mesh size than that of the APS–MPC–MB(4) gel due to the decrease in crosslinking density.

Cytocompatibility of the PMPC hydrogels. a Experimental procedure for investigating cell viability using culture media containing extracts from hydrogels. b Cell viability of L929 cells after incubation with extracts (100%) of ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels in the as-prepared and swollen states (n = 6). The extract medium had a concentration of 100%. c Cell viability of L929 cells after incubation with extracts (100, 50, 25, and 12.5%) of the as-prepared hydrogels (n = 6). d Cell viability of L929 cells after incubation with extracts (100, 50, 25, and 12.5%) of the swollen hydrogels (n = 6). Error bars indicate the standard deviation. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and n.s.>0.05

In the field of biomaterials, zwitterionic polymers have been identified as biocompatible materials owing to the weak interaction between biomolecules and zwitterionic moieties [36]. Among zwitterionic polymers, PMPC exhibits superior properties, including blood compatibility [37, 38]. A biocompatibility mechanism was reported by Nagasawa et al., who stated that water molecules strongly interact with grafted PMPC chains to suppress the adhesion of biomolecules such as proteins [39]. Unlike in those studies, the ADIP–MPC–MB(4) and APS–MPC–MB(4) gels exhibited unexpected adhesiveness. This can be attributed to the difference in the polymer structures. Hydrogels composed of a 3D network structure can interact with substrates and exhibit adhesiveness. In designing adhesive hydrogels, researchers typically investigate composite structures, interpenetrating polymer networks, and adhesive molecules, such as dopamine [14, 40]. However, owing to the complexity of material design, appropriately tuning the properties of hydrogels is sometimes difficult. In this study, we successfully prepared adhesive hydrogels based on a facile chemically crosslinked hydrogel controlled by the reactivity of the radical copolymer and initiator. In particular, ADIP was found to be suitable for synthesizing adhesive hydrogels under a high crosslinker concentration. As the reaction mechanism of FRP is universal, it is expected that a different initiator with similar properties to ADIP could produce a hydrogel with similar physical properties.

Conclusion

In this study, we report highly deformable adhesive hydrogels composed solely of monomers and chemical crosslinkers (pure adhesive hydrogels) prepared using a cationic radical initiator. We discovered that the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel, that is, a PMPC gel prepared with an acrylamide-type MB crosslinker (4 mol% MPC) and ADIP as a radical initiator, was viscoelastic, deformable, and adhesive. In terms of adhesion, the ADIP-MPC-MB(4) gel was tolerant to peeling, and the adhesion energy of the viscoelastic gel increased as the contact time with the adhesion target increased. The formation mechanism of this deformable and adhesive hydrogel was investigated by analyzing its polymerization behavior, and the following features were identified: the molecular weight of the polymer synthesized with ADIP was lower than that of the polymer synthesized with APS/TEMED, a conventional redox radical initiator. Moreover, analysis of the reactivity of various monomers and crosslinkers indicated the low reactivity of the acrylamide-type crosslinker MB toward methacrylate-type monomers. The cell viability test using the hydrogel extracts indicated the potential of “pure adhesive” PMPC hydrogels prepared with ADIP as biomaterials.

Radical copolymerization is one of the most versatile methods for designing functional hydrogels owing to the availability of various monomers. Hence, the reactivity of the monomer and chemical crosslinker strongly influences the hydrogel properties. We envision that a strategy for producing highly deformable and adhesive hydrogels by controlling radical copolymerization and initiator reactivity can serve as a useful guideline for designing adhesive hydrogels as biomaterials.

Experimental section

Materials

The MPC monomer was purchased from NOF Corporation. mOEGMA (molecular weight: 300) and the crosslinker PEGDM (molecular weight: 550) were purchased from Sigma‒Aldrich. ADIP was synthesized according to the procedure described in a previous study [23]. Other chemicals were purchased from FUJIFILM Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, unless otherwise noted.

Preparation of hydrogels

The ADIP–MPC–MB(4) gel was prepared as follows. MPC (1.33 g, 4.5 mmol), MB (28 mg, 0.18 mmol; 4 mol% monomer), and ADIP (27 mg, 0.045 mmol; 1 mol% monomer) were dissolved in water (3 mL) in an ice bath to prepare a pre-gel solution. The oxygen in the pre-gel solution was removed by bubbling with Ar gas for 5 min in an ice bath. Next, the deoxygenated pre-gel solution was injected into molds (thickness of 1 mm and diameter of 3 cm for rheology experiments), and polymerization was conducted at 25 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the prepared gels were removed from the molds and used for the experiments. For the tensile and adhesion tests, the gels were prepared without Ar bubbling because the use of APS/TEMED and ADIP as radical initiators protected the polymerization reaction from oxygen.

Dynamic viscoelasticity measurements

The storage and loss moduli were measured at 25 °C using a rheometer (MCR302, Anton Paar) with parallel-plate geometry (diameter: 25 mm). The applied oscillatory shear strain and frequency were 1.0% and 0.1–10 Hz, respectively. For dynamic viscoelasticity measurements, circular membrane-shaped hydrogels with a thickness of 1 mm and diameter of 3 cm were used.

Compression and tensile tests

Compression and tensile tests were performed using a universal testing machine (EZ-SX). For the compression tests, a disk-shaped hydrogel sample with a diameter of 15 mm was used at a deformation rate of 1 mm/min. For the tensile tests, a rectangular hydrogel sample with a thickness of 2 mm, width of 9 mm, and length of 20 mm, including the gripping part (5 mm for each end), was used. The deformation rate was set to 10 mm/min.

Adhesion tests

The hydrogels for the adhesion tests were prepared using a mold with an area of 1 cm × 1 cm and a thickness of 1 mm. The adhesion tests were performed using a universal testing machine (EZ-SX). The hydrogel samples were detached from the target (glass substrate) along the normal axis of the contact plane at a stroke rate of 0.5 mm/min.

Measurements of swelling ratio, sol fraction, and gel content

The as-prepared hydrogels were immersed in water for 2 days to obtain swollen hydrogels. The hydrogels were then freeze-dried. The swelling ratio was determined as Ws/Wd (Ws: weight of the swollen hydrogel; Wd: weight of the dried gel).

The sol fraction and gel content of the as-prepared samples were estimated as follows: the as-prepared hydrogels were immersed in water for 2 days, and the outer solution was collected. The solutes in the outer solution were obtained by freeze drying. The sol fraction (Fsol) was determined as follows: Fsol = Wsol/Winitial × 100% (Wsol: weight of obtained solutes, Winitial: weight of as-prepared hydrogel). The gel content (Fg) was determined as follows: Fg = 100 – Fsol (%).

Synthesis and characterization of linear PMPC

Linear PMPC with ADIP was prepared without chemical crosslinking as follows: MPC (1.33 g, 4.5 mmol) and ADIP (27 mg, 0.045 mmol; 1 mol% to monomer) were dissolved in water (3 mL) in an ice bath, followed by Ar bubbling for 5 min. Polymerization was conducted at 25 °C for 24 h with stirring. The reaction solution was dialyzed against water using a dialysis membrane (molecular weight cutoff (MWCO): 14,000) and freeze-dried to recover the polymer. Linear PMPC with APS/TEMED as a radical initiator (1 mol% to monomer) was synthesized in the same manner.

Monomer conversion was determined by analyzing the reaction solution without purification by 1H NMR using a JEOL ECS-400 spectrometer (JEOL). The generated polymers were analyzed using a GPC system equipped with an OHpak SB-804 HQ column (Shodex) and a reflective index detector (RI-2031 plus, Jasco). The eluent for GPC was a = 7/3 (v/v) methanol/water-mixed solvent containing 50 mM LiCl at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The molecular weight was determined using poly(ethylene glycol) as a standard. The viscosity (η) of the purified linear polymer in 100 mM NaCl was measured by a digital viscosity meter (VM-10A, Sekonic) with different concentrations (c) of the polymer. The specific viscosity (ηsp) was calculated by the following equation:

where η0 is the viscosity of the solvent. The reduced viscosity (ηred) was calculated by the following equation:

The intrinsic viscosity was determined as the intercept of the ηred–c plot.

Analysis of the reactivity of the monomer and crosslinker

The method for analyzing the reactivity of a monomer and a crosslinker is as follows. MPC (monomer) and MB (crosslinker) were dissolved in water to obtain a total monomer concentration of 0.35 M. An aliquot (60 µL) was collected, mixed with D2O (500 µL), and analyzed by 1H NMR to determine the monomer composition before polymerization. An aqueous solution containing ADIP as the initiator was added to the solution containing the monomer and crosslinker, followed by Ar bubbling for 5 min. The reaction mixture was incubated at 25 °C for 2 h. Subsequently, an aliquot (60 µL) was collected from the solution and mixed with D2O (500 µL). This solution was analyzed using 1H NMR spectroscopy to determine the conversion of MPC to MB. The peaks at 6.06 and 6.12 ppm, which correspond to the protons bonded to C = C in MPC and MB, respectively, were used for the calculations (Fig. S8 in the Supporting Information).

Cell cytotoxicity tests

The cytotoxicity of the hydrogel extracts was analyzed using a CCK-8 assay, as shown in Fig. 5a. The hydrogels were prepared as described in the subsection “Preparation of hydrogels.” The hydrogels were used as prepared or after swelling in water for 2 days by changing the external aqueous solution. The hydrogels (0.2 g for each sample) were immersed in 4 mL of DMEM containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Subsequently, the supernatant (approximately 2 mL) was collected, the hydrogels were removed, and the samples were centrifuged. Fetal bovine serum (FBS) was added at a concentration of 10% prior to use. In addition, a dilution series (50%, 25%, and 12.5% by volume) of the cell culture medium was prepared by mixing DMEM containing 1% and 10% FBS. When the culture medium containing the hydrogel extract was used at its original concentration, it was denoted “100%”. The cell culture medium was dispensed at 100 µL/well as follows.

L929 cells were cultured in a 96-well plate (100 µL/well, 104 cells/mL) in an incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) with DMEM containing 1% P/S and 10% FBS as the culture medium. After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, the culture medium was exchanged with medium containing the hydrogel extract at dilutions of 100%, 50%, 25%, and 12.5%. L929 cells used as a control were cultured in DMEM containing 1% P/S and 10% FBS without the hydrogel extract, and the culture medium was exchanged in the same way. For each condition, six wells were used. After incubation for 24 h at 37 °C, the culture medium was exchanged with DMEM containing 1% P/S and 10% FBS. CCK-8 assay solution (10 µL) was added to each well, followed by incubation at 37 °C for 2 h in a CO2 incubator. Subsequently, the absorbance at 450 nm (A450) of the solution in each well was measured using a plate reader (ARVO X3, PerkinElmer). The viability was determined as the ratio of the A450 value of the sample cultured with extract to that of the control sample cultured in DMEM containing 1% P/S and 10% FBS.

Responses