Diagnosis and genomic characterization of the largest western equine encephalitis virus outbreak in Uruguay during 2023–2024

Introduction

Arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) are high-burden priority pathogens of global concern1. Among these, viruses belonging to the Alphavirus genus (Togaviridae family) inflict considerable morbidity and mortality in animals and humans2. This genus is broadly split into old world and new world alphaviruses, each with distinct characteristics and impact on health3,4,5. The old world alphaviruses comprise Semliki Forest, O’Nyong-nyong, Ross River, chikungunya, and Sindbis viruses. The new world alphaviruses include the Mayaro virus, the Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, the Eastern equine encephalitis virus, and the Western equine encephalitis virus6.

The Western equine encephalitis virus (WEEV) is transmitted between mosquitoes (Culex tarsalis in North America and Aedes albifasciatus in South America) and avian hosts, having wild birds as primary enzootic cycle reservoirs7,8. The virus might spill over into horses and human populations through mosquitoes that opportunistically feed on mammals and start epizootic cycles. Equine and human infections, though typically asymptomatic, can lead to severe encephalitis and death, with case-fatality rates ranging from 3% to 4% in humans and 15–20% in equines9. Horses and humans are dead-end hosts and do not contribute to further epizootic transmissions7. There are no effective treatments for active WEEV infection, but vaccines are available for the prophylactic therapy of equines10.

Most data available from WEEV epizootic outbreaks was registered from passive surveillance and outbreak events between the 1940s and the 1990s in North America. The first large-scale outbreak was recorded in the western United States around 1940, with about half a million equine cases and many thousands of human infections11, followed by another significant outbreak in the 1980s in the United States and Canada12. In Mexico, epizootics involving more than 41 horses were reported in 201913. Over the past decades, infections in the United States and Canada have dropped significantly14,15,16.

In South America, WEEV infections were reported in 1933 in Argentina and in the 1950s in Brazil17. Epizootics and human circulation also occurred in 1972–1973 and 1982–1983 in Argentina and Uruguay18,19,20. Some sporadic human cases were also reported until 200918,21,22. Lastly, WEEV outbreaks were also reported in northeastern Brazil in 201123, and antibodies to the virus were sporadically detected in immune sera obtained from Brazilian and Uruguayan animal populations24,25,26.

WEEV diagnosis and classification were initially conducted using serological methods and, more recently, through genomic phylogenetic and phylodynamic analyses27. The WEEV genome comprises a positive-sense, single-stranded RNA molecule of approximately 11.7 Kb in length. Non-coding regions flank it at the 5′ and 3′ ends and are involved in virus replication and translation28. The genomic RNA encodes four nonstructural proteins (nsP1 to nsP4). A subgenomic RNA encodes five structural proteins: a nucleocapsid protein (C), two envelope glycoproteins (E3 and E2), and two smaller accessory peptides (6K and E1). Envelope glycoprotein heterodimer (E1 + E2) contains virus-specific neutralizing epitopes; nucleocapsid protein has broadly cross-reactive epitopes with other alphaviruses.

Studies of WEEV were limited in recent years due to the pathogen’s submergence14. Detailed phylogenetic analysis of WEEV has been mainly restricted to North American strains14,15,29. The A, B1, B2, B3, and C1 groups were proposed to characterize the WEEV variability. Groups A and B are composed mainly of North American strains, but a recently described group C was proposed for one ancient strain from Argentina and three strains collected in 2024 from Brazilian municipalities bordering Uruguay30. However, remarkably few genomes from South America were available, making it difficult to determine their phylogenetic relationships with the remaining sequences.

The most recent large WEEV outbreak unfolded in the Southern cone of South America from November 2023 to April 2024, affecting approximately 2500 equines and humans in Argentina and Uruguay27,31. In Brazil, only three infected equines have been identified by retrospective analyses of deceased horses suspected of rabies infection30.

Due to the large scale of Argentina and Uruguay outbreaks, the Pan American Health Organization/World Health Organization issued an epidemiological alert on the risk to human health associated with WEEV infection in December 2023, emphasizing the importance of strengthening epidemiological surveillance, diagnosis, intersectoral coordination, and vector control. As part of a coordinated response to this unfolding emergency, we present the epidemiological and genomic characterization of the largest WEEV outbreak in Uruguay from 2023 to 2024. This was possible by developing and testing a new next-generation sequencing protocol for WEEV diagnostic and characterization. Our findings reveal the evolutionary trends and rapid expansion of WEEV in the country and at international borders. We also identified genomic variability that affects WEEV qPCR primers and probes specificities of referenced protocols for diagnostics27, highlighting the need for diagnostic assay reevaluation.

Materials and methods

Dataset and sampling collection

The Ministry of Livestock, Agriculture, and Fisheries (MGAP) collected all the samples and data on the horses affected by the outbreak, including date, location, number of infected animals, clinical signs, and disease outcome. To display this data, we set up a Microreact instance32, which harbors the whole dataset from positive cases in Uruguay.

Samples for genetic studies corresponded to brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid collected from deceased horses exhibiting clinical signs of encephalitis. These samples from the outbreak’s peak were transported under refrigerated conditions for molecular diagnosis (Table 1).

WEEV diagnosis

Total RNA extraction was performed using the taco™ Automatic Nucleic Acid Extraction System (GeneReach Biotechnology, Taiwan, China). The virus was initially identified using a generic nested PCR to detect and classify alphaviruses33. The nested PCR targeted the nsP4 (RNA-dependent RNA polymerase) region and produced a 481 bp-long amplicon in the first PCR round and a 195 bp-long amplicon in the second one. Complementary DNA (cDNA) and the first PCR round were performed using AgPath-IDTM One-Step RT-PCR reagents (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, USA). The second round used PlatinumTM Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, USA).

WEEV was confirmed by the RT-qPCR described by Lambert et al.34 and suggested by the WOAH terrestrial manual35. This hydrolysis probe-based assay amplifies a 67 bp fragment in the E1 coding region. An alternative WEEV-specific RT-qPCR method was also applied for comparison purposes36. This assay also uses a hydrolysis probe and amplifies an 80 bp fragment within the E2 coding region. Amplification reactions were conducted using a 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Waltham, MA, USA) and the MIC-4 Thermal Cycler Real-time qPCR (Bio Molecular Systems BMS. Australia).

Amplicon-based next-generation sequencing (NGS)

Primer design

All available full-length WEEV genomes were retrieved from the NCBI database to generate a comprehensive dataset. Multiple alignments were performed using MAFFT v7.490 in Geneious Prime® 2023.1.237. To enrich the viral genome before massive sequencing, we designed primer sets generating overlapping amplicons covering the entire genome. The suitability of each primer was evaluated using the OligoAnalyzerTM tool from IDT (https://www.idtdna.com/pages/tools/oligoanalyzer) to ensure optimal Tm and avoidance of hairpin and dimer structures.

Multiplex PCR-NGS reaction

The Illumina Microbial Amplicon Prep (IMAP) kit was used to construct amplicon-based libraries, following the manufacturer’s protocol. Each sample underwent an RT reaction with 8.5 μL of total RNA, followed by two multiplex-PCR amplification reactions (pools 1 and 2) using 5 μL of cDNA. Each primer was used at a final concentration of 0.4 μM. The PCR cycling protocol was the same for both pools. It consisted of an initial denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, and an annealing/extension step at 60 °C for 2 min. A final extension step at 72 °C for 5 min completed the amplification process. Generation of the expected amplicons was verified by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis. Subsequently, 10 μL from each PCR reaction (pools 1 and 2) was pooled and subjected to tagmentation and indexing. The library’s quality and fragment length distribution were assessed using the Agilent high-sensitivity DNA kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) on a Fragment Analyzer™ System (Advanced Analytical Technologies Inc., Heidelberg, Germany). Genome sequencing was performed on an Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina, USA) using the MiSeq Reagent Kit v2 (300 cycles).

Genome assembly

The raw data was processed using the Geneious BBDuk v38.84 tool. Illumina adapters and primer sequences were removed, and low-quality reads (Phred quality scores < 30) were filtered out. The remaining reads were aligned to MN477208 as the reference genome using Minimap2 v2.17 (Li, 2018). Assemblies were visually and manually curated to generate majority consensus sequences; annotations were transferred from reference strains.

Phylogenetic analysis

We obtained all WEEV genomes larger than 7 Kb from the BV-BRC database on 25.02.2024 for a detailed phylogenetic analysis.

The dataset includes 71 WEEV sequences collected from 1930 to 2024: 45 from North America and 25 from South America. There are also individual sequences from Russia (1962) and Cuba (1970). The North American sequences are sourced from various hosts, including birds, mosquitos, horses, and humans, while the South American sequences predominantly come from horses. This dataset included six recently submitted Uruguayan strains (PP620641–PP620646) obtained through a probe-capture enrichment NGS assay.

Recombination was assessed with the RDP program in the dataset utilized for phylogenetic analysis38. Maximum-likelihood trees were inferred from IQTREE v2.1.2, and FastTree v2.1.11 was implemented within Geneious39. We also investigated the temporal signal of the current 2023–2024 outbreak samples. The root-to-tip divergence was low (R ~ 0.45); therefore, we performed a phylogenetic reconstruction with no temporal scale. The resulting tree was midpoint rooted as it was unclear which sister alphavirus should be used as an outgroup.

Identification of amino acid markers and positively selected sites

Using the same genomic dataset as in the phylogenetic analysis, we visually inspected the translated alignments to identify residues (markers) characteristic of phylogenetically related sequences. We also checked the occurrence of amino acid substitutions that were previously described as phenotypically relevant14.

Individual sites subjected to positive selection were identified using the mixed effects model of evolution software40.

Results

Virus identification and diagnosis

WEEV was initially characterized as the causative agent of the outbreak by sequencing a 195 bp amplicon of nsP4 generated via a generic RT-nested PCR assay33. Once identified, the virus was diagnosed using the qPCR methods described by Lambert et al. and Brault et al.34,36. The Ct values obtained with the Lambert et al. method were relatively high, with an average Ct value of 36.5 (Table 1). When the Brault et al. method was applied to the same samples, lower Ct values were obtained in all cases, with an average Ct value of 27.5 (Table 1).

Epidemiological characterization of the outbreak

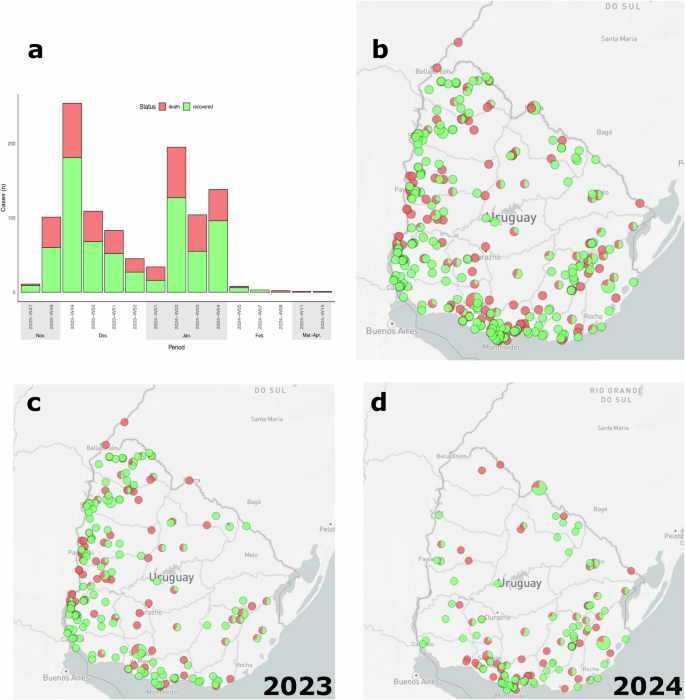

Equine cases were tracked from November 28, 2023, to April 10, 2024. Mortality and morbidity were determined over an estimated equine population of 405,644 animals. The number of equines exposed to the WEEV infection was 16,863 from 605 establishments (farms, ranches, racecourses, and backyards) (https://microreact.org/project/gofP6cvtZmUv2ZMaGExUYC-weevuruguayrs). The virus affected 1086 horses, including 80 confirmed cases with molecular diagnostics, and produced 388 deaths across all 19 Uruguayan Departments (https://microreact.org/project/nvwRMyT8EVHq4yqbpUiM6v-weevuruguayrspositive) (Fig. 1a, b).

a Histogram plot illustrating the distribution of WEEV-positive cases in Uruguay during 2023–2024. b Geographic distribution of WEEV-positive cases during 2023–2024. c WEEV-positive cases during 2023 are located mainly in regions bordering Argentina. d WEEV-positive cases during 2024 are primarily located in central and eastern regions.

Clinical signs of WEEV infection in horses include fever, anorexia, and depression. In severe cases, disease progression leads to hyperexcitability, blindness, ataxia, severe neurologic depression, recumbency, convulsions, and death.

The number of infected horses showing clinical symptoms and death increased from November 2023, reaching its peak in the first weeks of December 2023 (Fig. 1a). These 2023 cases were primarily concentrated in the Uruguayan departments that border Argentina (Fig. 1c). This was followed by a decrease between the second half of December and the first week of January 2024 and a new increase in cases in the second week of January 2024. This second peak in 2024 was more concentrated in the central and east departments of Uruguay (Fig. 1d).

Developing a new NGS protocol for obtaining WEEV genomes

Nine primer sets were designed within conserved genome regions, incorporating degenerate bases as necessary (Table 2). Amplicons range from 1031 bp to 1736 bp, with overlapping areas averaging 100 bp (Supplementary Fig. 1). Amplicons were obtained in two independent multiplex reactions (pools 1 and 2) to avoid amplifying overlapping regions. Most samples yielded the expected numbers and lengths of amplicons, producing five amplicons for pool 1 and four for pool 2.

The nine amplicons were included in IMAP Illumina libraries and sequenced. Filtered reads were aligned with the reference genome, resulting in 15 full-length and 4 partial genome sequences, exhibiting breadth coverage ranging from 53.6% to 94.2%. Two strains previously sequenced by probe-capture NGS sequencing (PP620641 and PP620642) were re-sequenced in the current study (Table 1).

NGS of complete WEEV genomes produced an average of 481,750 reads per sample, ranging from 268,709 to 1,489,6367 reads. The mean coverage depth of CDS regions ranged from 765× to 17,322×.

Genome characterization and variability

The 15 full-length consensus sequences generated (11,216 nt) have an 11,159 nt coding sequence (CDS). Overall, these WEEV genomes were highly conserved, with a nucleotide similarity ranging from 99.75% to 100% and an amino acid similarity of 99.78–100%. Nonstructural protein genes (nsP1–nsP4) showed similar levels of heterogeneity as structural protein genes (C, E3, E2, 6K, and E1), with an average nucleotide similarity ranging from 98.99% (nsP3) to 99.37% (C) and an average amino acid similarity ranging from 99.34% (nsP3) to 99.92% (E3).

Phylogenetic analysis

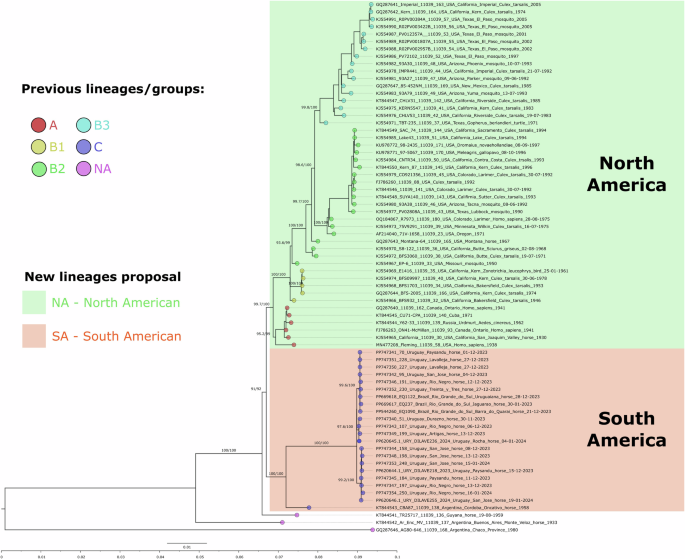

There was no significant evidence of recombination in the entire genomic dataset analyzed. The maximum-likelihood (ML) phylogeny of the genome data set shows that most WEEV sequences belong to either a North American (NA) or South America (SA) lineage (Fig. 2). These NA and SA lineages share a common ancestor and have three basal South American strains (two from Argentina and one from Guyana). The NA lineage is divided into sublineages A and B. The A sublineage includes mosquitoes, humans, and horse samples collected from 1930 to 1971 in the United States, Canada, Russia, and Cuba. The B sublineage includes samples from mosquitoes and horses from 1946 to 2005. Within sublineage B are three genogroups: B1, B2, and B315; B1 and B2 are paraphyletic, and B3 is monophyletic.

WEEV genomes, including the 15 genomes from the current 2023–24 outbreak. Tip color follows groups and lineages previously reported in the literature (NA: not available). The new proposed North American (green) and South American (orange) lineages are depicted. Branch supports depicted above each branch are aLRT and ultrafast bootstrap.

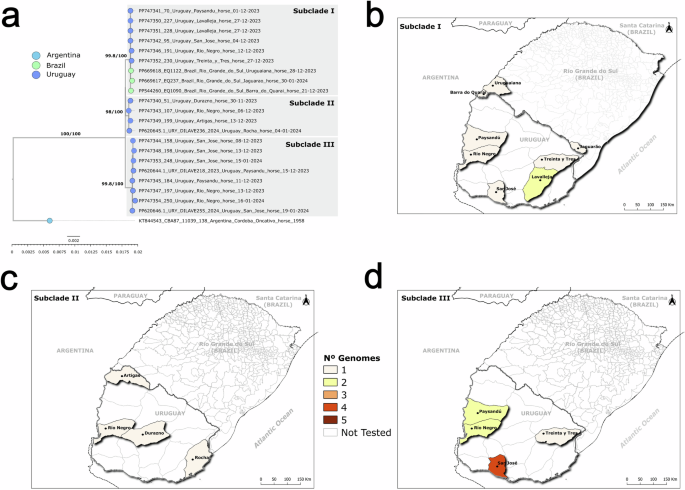

The SA lineage encompasses a monophyletic clade with the synchronic horse samples from Uruguay and Brazil collected during 2023–2024 and a basal Argentine strain from 1958 (KT844543). The Brazilian and Uruguayan 2023–2024 clade is divided into three subclades: I, II, and III (aLRT/UFBOOTS > 98) (Fig. 3). Strains from Brazil and Uruguay are clustered in subclades I, while subclades II and III are composed of genomes from Uruguay only (Fig. 3a). The subclade strains are widely distributed across various Uruguayan Departments (Fig. 3b–d) and exhibit a clear polytomy, evidencing low within-clade genetic variability and fast strain spreading.

a Zoom of the clade, including an early Argentina strain (1958) and the 23 strains from the 2023–24 outbreak. Tip colors are countries of origin. Branch supports are aLRT and ultrafast bootstrap values. b Geographic distribution of subclade I samples from Uruguay and Brazil. c Geographic distribution of Uruguayan subclade II samples. d Geographic distribution of Uruguayan subclade III samples. Heat map colors indicate the number of genomes per department.

Amino acid markers

Different amino acid markers defined the monophyletic groups described in this study (Table 3). The SA lineage has five markers in the nonstructural proteins and two in the protein E1. The 2023–2024 clade depicted three markers in the nonstructural proteins and one in E1. The three subclades of the 2023–2024 outbreak contained one or three unique residues in the nonstructural, E3, and E1 proteins.

We found evidence of episodic positive/diversifying selection at 42 sites of the WEEV proteins. Six varying positions (nsP2-418, nsP2-460, nsP3-359, nsP4-112, E1-55, and E1-213) in the South American phylogenetic groups have evidence of positive selection. The position sites of the 2023–2024 outbreak did not show signs of positive selection.

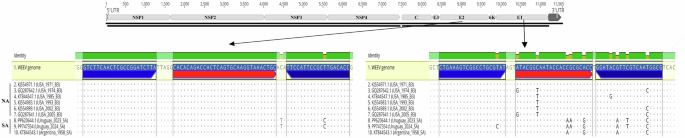

Variability in target qPCR sequences

Our analysis of complete WEEV genome sequences revealed a single mismatch in a primer delineated by Brault et al.36 and several mismatches in the probes and primers outlined by Lambert et al.34(Fig. 4).

Top: representation of the WEEV genome showing qPCR target regions. Right bottom: alignment of the probe and primer regions of the official qPCR diagnostic protocol targeting the E1 coding region34. Several SNPs may affect the binding effectivity of primers and probes to South American strains. Left bottom: alignment of the probe and primer regions of an alternative qPCR assay targeting the E2 coding region36. These regions are more conserved among WEEV strains.

In Brault’s assay, we identified a mismatch in the reverse primer (19 nt) exhibited in the 2023–2024 clade but not in the basal strain within the SA lineage.

The differences were notably more pronounced in Lambert’s assay, where mismatches were observed in both NA and SA lineages. Within the NA lineage (B3 genogroup), strains exhibited one to two mismatches in the 23-nt long probe, while the basal strain and strains from the 2023–2024 clade in the SA lineage showed two to three mismatches. Moreover, certain strains within the 2023–2024 clade of the SA lineage displayed a mismatch with the forward primer (20 nt). The reverse primer (20 nt) exhibited one to three differences across variants from both NA and SA lineages (Fig. 4).

Discussion

WEEV was responsible for large human and equine outbreaks in western North America throughout the early to mid-20th century, leading to thousands of equine and human deaths due to encephalitis. However, during the late 20th century, a marked reduction in WEEV transmission was recorded, with the last human case documented in 1998 and a decrease in infected mosquito pools identified in longitudinal surveillance programs14,15,16.

A similar trend has occurred in South America in recent decades, with only sporadic cases occurring after the 1980s22. This period of epidemiological silence contrasts with the present outbreak from 2023 to 2024, one of the largest and deadliest in South America’s history.

Although the clinical data suggested an equine encephalitis virus, the outbreak was unequivocally characterized by sequencing a conserved RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (nsP4) region that distinguishes WEEV from other related alphaviruses33. The WEEV identification allowed the deployment of more cost and time-effective qPCR methods, including the PAHO/WHO recommended assay27,34. However, the Lambert et al. methodology34 performed poorly in Uruguayan strains, likely due to the mismatches in probes and PCR primers (Fig. 4). In comparison, the alternative method described by Brault et al.36 showed greater homology in the target region of the 2023–2024 outbreak strains, resulting in lower Ct values and improved sensitivity (Fig. 4).

The 2023–2024 outbreak affected 1419 equine and 58 human cases in Argentina. In Uruguay, it impacted 1086 equines, with approximately 35% of them dying from severe neurological symptoms. Considering that Argentina has eight times more horses than Uruguay41, the outbreak has been particularly severe in Uruguay. However, it is important to note that differences in reporting may exist. The estimated mortality (horse deaths/population size = 388/405,644) was 0.09%, and the morbidity (affected horses/population size = 1086/405,644) was 0.26%. During the outbreak, vaccination was recommended for the affected ranches and equine gathering events (Resolution N° 282, MGAP). The Ministry of Public Health reported five human WEEV cases during the same period. These findings underscore the threat of WEEV to equine and human health and highlight the need for ongoing surveillance.

In the last decade, studies of infectious diseases have benefited from the development of new genomic tools, allowing real-time monitoring of new outbreaks. These tools facilitate the identification of the origin, routes of transmission, and control of viral pathogens42,43,44. Next-generation sequencing has been the most powerful method for obtaining genomes to map viral genetic variability45,46,47. During the present study, we developed a next-generation methodology for sequencing WEEV genomes directly from clinical samples. This technique uses PCR enrichment, the most affordable and straightforward procedure, to increase the viral-to-host genome ratio48,49. Previous studies have employed direct sequencing on WEEV cell culture50 or capture hybridization probes for viral DNA/RNA enrichment30. These alternative enrichment techniques are effective but time-consuming (culture) and comparatively expensive (capture probes), making them more challenging to apply in low-resource setting laboratories.

The multiplex-NGS methodology applied to the 2023–2024 South American outbreak yielded 15 complete genomes directly from deceased horse samples. These new WEEV sequence data significantly increased the number of publicly available genomes in GenBank and allowed us to perform the first large-scale genomic study of this arbovirus in South America. Our findings support the existence of two main lineages of WEEV. The North American lineage contains strains from various hosts (mosquitoes, birds, horses, and humans) collected from 1930 to 2005. These strains were relatively genetically stable, with only a maximum of 3.7% nucleotide sequence divergence15. This lineage was extensively described and divided into groups A and B. Group B comprised three genogroups (B1–B3) that are not necessarily monophyletic, bearing specific amino acid markers and circulation periods14,51. Group A includes the original California strain (KJ554965.1), obtained from a horse in 1930, the human isolate McMillan (GQ287640.1) from Canada (1941), the Fleming strains (MN477208.1) from the USA, and strains from Russia and Cuba. In the United States, group A might have become extinct in the 1940s and was displaced by Group B, which became predominant. Strains from ancestral groups A and B1 are generally more virulent than recent strains from groups B2 and B3. When all three group B sublineages were circulating, there was a concurrent increase in estimated viral population size between 1965 and the late 1980s. However, after the late 1980s, a reduction in estimated population size occurred when the group B3 viruses became predominant in North America14,15.

South America has a more limited strain diversification than North America, possibly due to the fewer available strains from historical outbreaks. The South American lineage comprises horse strains from 2023 and 2024 (Uruguay and Brazil) and the CBA87 strain collected in 1958 from Argentina (Córdoba).

The two American lineages have a common ancestor, suggesting that the ancestral WEEV diversified into North and South lineages. The phylogenetic tree included strains from Argentina and Guyana as basal branches, raising the possibility that the common ancestor originated in South America and spread north and south. The ancient WEEV strains in SA and NA lineages dated back to the 1930s, suggesting that the divergence occurred at least a hundred years ago. Further analysis would require extensive sampling from different countries and periods, particularly in South America.

The 2023–2024 outbreak started in Argentina and was later detected in Uruguay and Brazil. Strains from Uruguay and Brazil are closely related and bear several clade-specific mutations. They are here denoted as a clade because they compose a monophyletic group, share a recent common ancestor, and are synchronous. This clade comprises the Uruguayan and Brazilian subclade I and the Uruguayan unique monophyletic subclades II and III (Fig. 3). The Argentine CBA87 strain collected in 1958 from a horse is basal for the 2023–2024 outbreak clade. This old Argentine strain might represent an ancestor of the outbreak’s source that persisted in an enzootic transmission cycle.

We analyzed the 2023–2024 clade to determine the presence of neurovirulence and transmission markers previously described. All the 2023–2024 clade strains contained the E2-214R residue previously associated with low neurovirulence in a murine model52. Residue E2-214R was also identified as necessary for the efficient infection of the mosquito vector C. tarsalis52. Additionally, the 2023–2024 clade lacks the six amino acid mutations previously described to increase fitness in avian and mosquito hosts (nsP3-152I, nsP4-602S, C-89R, C-250W, E2-23T, and E1-374S)14. The clade contains all six residues resembling the ancestral, less fit state (nsP3-152T, nsP4-602N, C-89K, C-250K, E2-23A, and E1-374T).

Our analysis revealed no marker linked to distinct WEEV phenotypic changes. All the unique amino acid markers detected in our analysis that have not been previously studied for their virulence or transmission characteristics should be considered subclade markers.

Some of the residues that distinguish the phylogenetics groups in South American strains have evidence of positive selection. These residues map the nonstructural proteins (nsP2, nsP3, and nsP4) and the surface glycoprotein E1 responsible for cell fusion. E1 is located underneath the E2 protein on the virion and is mainly concealed on the mature virion, making it inaccessible to antiviral antibodies53,54. Whether these markers have functional implications or are influenced by the mosquito or avian species involved remains unanswered, highlighting the need for further research.

Interestingly, the 2023–2024 outbreak spread rapidly in Uruguay, beginning in the region bordering Argentina and reaching the central and eastern areas. This spread pattern aligns with WEEV emerging in Argentina and spreading to Uruguay following a west-to-east expansion (Fig. 1). Similar behavior may have occurred in Brazil, where municipalities in the West detected the first cases, followed by a city from the East part of Rio Grande do Sul state.

Historically, equine encephalitis activity follows multiyear cycles, with epidemics occurring after periods of excessive rainfall starting during the preceding year55,56. In November and December 2023, the weather in neighboring Argentina, Brazil, and Uruguay regions showed high temperatures and rain, leading to mosquito proliferation, particularly those of the A. albifasciatus species. The virus may have emerged in Argentina from genetically close strains that invaded Uruguay and Brazil. Genetic polymorphisms in the original Argentine viral population and different cross-border transmission events would explain the different subclades observed in Uruguay and Brazil (Fig. 3a).

Mosquitoes have a narrow flight range of less than a kilometer, and horse transportation between regions does not impact the transmission because the viremia in these animals is insufficient to infect new mosquitoes. Birds and, to a lesser extent, some mammals, such as lagomorphs and rodents, are the amplification hosts that transmit the virus to the local mosquito population22. House sparrows are a natural enzootic amplification/reservoir host for WEEV in North America, developing a high-titer, short-lived viremia that peaks on day 1 post-infection without detectable morbidity.

Therefore, wild birds with fast displacement across the country are the more likely amplification host associated with transmission. The outbreak coincided with migratory and indigenous birds arriving in areas with abundant water sources, including wells, lakes, ponds, streams, or rivers. Migratory birds remain the most plausible means of transporting the virus to more distant areas.

A limitation of this study is the absence of molecular diagnostics in asymptomatic and recovered horses. The lack of Argentine WEEV sequences for comparison and the unavailability of sequences from mosquitoes, amplification hosts, and humans hinders a more comprehensive description of the outbreak’s epidemiological scenario.

Genomic epidemiology studies remain a priority for a better understanding of viruses’ biology and epidemiology and for developing effective treatments, vector control approaches, and vaccines. In this sense, we expect other researchers to adopt the method for NGS-sequencing WEEV genomes and adjust the qPCR methodology by considering the mismatches found in probes and primers. Our research emphasizes the importance of mapping the genetic diversity of WEEV in South America, which may uncover additional enzootic lineages beyond the three lineages identified in this study. Genomic surveillance for certain viruses in this region has been neglected, which hinders our ability to monitor, control, and prevent future outbreaks. The scientific community needs additional resources to improve our understanding of emerging and re-emerging pathogens that may affect animals and humans within a One Health approach.

Responses