Direct preparation of two-dimensional platelets from polymers enabled by accelerated seed formation

Main

Crystallization-driven self-assembly (CDSA) has emerged as a powerful method to fabricate anisotropic nanostructures, such as one-dimensional (1D) cylinders and two-dimensional (2D) platelets1,2. The vast array of stable, uniform nanostructures formed through this method has led to their diverse range of applications, including catalysis3,4, biomedical engineering5,6 and energy transfer7. Through ‘living CDSA’, these self-assembled systems can adopt high levels of precision, uniformity and complexity. Notably, living CDSA enables precise epitaxial growth of nanostructures upon the addition of further unimers. This method allows the size and shape of the self-assembled nanostructures to be tuned by adjusting the quantity and composition of the unimers added to the nucleated seeds in solution8,9.

Despite the application potential of CDSA-formed particles, the complex and time-intensive nature of seed preparation, which involves heating polymer solutions, extended ageing and sonication, presents substantial synthetic challenges that hinder their application at scale8,9. Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL)-based polymers, valued for their biodegradability and biocompatibility, have been effectively utilized in living CDSA to prepare 1D and 2D nanoparticles10,11,12,13,14. Typically, in this method, the initial transformation of bulk polymers into unimers is achieved through heating, followed by spontaneous nucleation during cooling. Due to the spontaneous formation of nucleation sites, the resulting 1D cylinders form over an extended ageing period, typically 1 week, and have a high dispersity (that is, a large distribution of cylinder lengths) and no size control. Subsequently, sonication is commonly used to fragment these cylinders to achieve uniform seeds10,12,14. Inconsistency in seed sizes upon increasing the volumes of dispersed cylinders that are subjected to sonication limits the synthesis of these uniform seeds to small-scale batches. Moreover, the transition from polymers to platelets involves multiple morphological changes and batch-to-batch processes. To achieve good size control and uniformity, living CDSA requires a dilute solution (typically less than 0.1 wt%), which in turn leads to a notable reduction in throughput2,8,15. Unsurprisingly, given the multiple steps required to transform polymers to platelets, scale-up is challenging. Although efforts have been made to scale CDSA, the obtained structures were predominantly 1D cylinders, with limited control over size and morphology. For example, the Manners and Patterson groups introduced polymerization-induced CDSA (PI-CDSA) to perform polymerization and CDSA simultaneously16,17,18, whereas the Winnik group conducted CDSA by co-self-assembly of block copolymers with trace amounts of homopolymer, leveraging controlled annealing and cooling conditions to produce uniform micelles at high polymer concentrations19.

We hypothesized that a transition from a batch process to a flow process would be a key enabler for efficient and reproducible preparation of high-quality seeds, while still maintaining excellent size control (uniformity throughout seed solution). Continuous-flow reactors, where reactants flow steadily through the reactor while chemical reactions occur concurrently, have been demonstrated to be an ideal way to scale up reactions20,21. We anticipated that minimization of the processing time would be essential to enable transition of the seed formation process into continuous flow. Therefore, we sought to favour spontaneous self-nucleation in a short window, so that we could develop a more efficient and, hence, more reproducible and scalable method to obtain uniform seeds.

While studying the formation of polydisperse cylinders, we noticed that self-nucleation could be favoured when the solution was cooled from a supersaturated state13,22. Inspired by reports of flash nanoprecipitation for polymer and peptide nanoparticles23,24,25, we anticipated that, if a highly supersaturated solution could be achieved, it would rapidly favour instantaneous nucleation to potentially provide a process that could be used in situ for the creation of complex multilayered 1D and 2D polymer particles, dramatically reducing the time it takes to make uniform platelets from polymers (from a week down to a few minutes) and allowing a leap forward in the scalable synthesis of precision nanoparticles. Here, we introduce a flash-freezing strategy to prepare seeds, leveraging excellent temperature control for seamless scale-up in flow. Building on this, an integrated flow cascade, combining seed formation and living CDSA, was established, enabling end-to-end production of platelets directly from polymers, significantly reducing processing time and increasing throughput.

Results and discussion

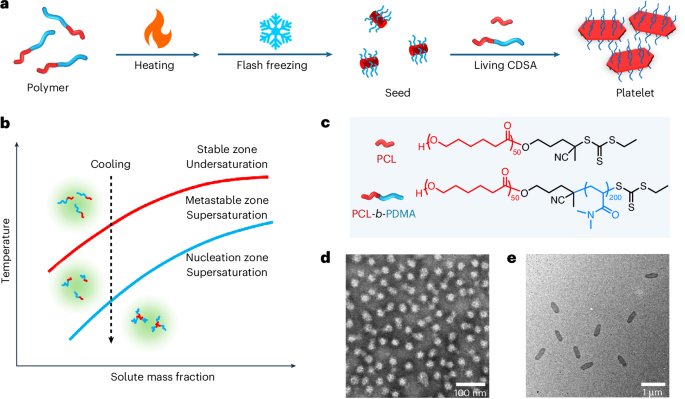

We used the established PCL homo (PCL50) and poly(ε-caprolactone)-block-polydimethylacrylamide diblock (PCL50–b-PDMA200) polymers, based on their demonstrated effectiveness in both seed and platelet preparation using conventional CDSA methods (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Figs. 1–6 and Supplementary Table 1)10,12,13. Initially, we focused on creating seeds in a rapid manner in a batch process. Unlike previous methods that formed seeds through the sonication of polydisperse cylinders, here we studied an in situ flash-freezing method to produce seeds in minutes by removing the time-consuming ageing process (Fig. 1a). To achieve this, the diblock polymer was initially dissolved in ethanol at elevated temperature, to generate an undersaturated solution. The solution was subsequently cooled rapidly (flash freezing) to induce spontaneous nucleation and generate uniform seeds. Conditions such as heating and cooling times and polymer concentration were studied in batch to explore the best conditions for preparing flash-frozen seeds (Supplementary Table 2). Optimal conditions were found when the diblock polymer solution was prepared by heating at 75 °C and then quenched using a dry-ice–acetone bath, with the production of uniform seeds, as shown by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis (Fig. 1d). Other methods, namely ice and air cooling, resulted in long cylinders and large aggregates (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8). While these particles exhibit higher melting points due to slow crystallization kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 9), their irregular structures and low crystallization rate during air cooling make them unsuitable as seeds because of low preparation efficiency. Further optimization towards smaller and more uniform seeds was achieved by heating the diblock polymer solution for longer time periods, with the size of the flash-frozen seeds constant at 50 nm (characterized by dynamic light scattering (DLS)) for all time periods >2 min (Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11). This suggests that, if the solution is not thoroughly heated, regional chain entanglement or aggregation can induce large particle formation during cooling. Seed particle sizes were also influenced by the concentration of diblock polymer solution such that the size of the seeds decreased with increasing concentration but reached a plateau at 50 nm when the concentration exceeded 0.05 mg ml−1 (Supplementary Figs. 12 and 13). This is consistent with a lower polymer concentration leading to lower supersaturation levels upon flash-freezing, thereby reducing self-nucleation and forming large seeds.

a, Scheme to prepare platelets from polymers via flash-frozen seeds. b, A phase diagram illustrating diblock polymer crystallization using the flash-freezing strategy. c, Chemical structures of PCL-based homo and diblock polymers. d, A TEM image of flash-frozen seeds prepared at 0.1 mg ml−1 with 2 min heating at 75 °C and 1 min cooling in a dry-ice–acetone bath. The seed sample was stained by 1 wt% uranyl acetate aqueous solution. e, A TEM image of platelets prepared by living CDSA using flash-frozen seeds.

Further exploration of the cooling conditions demonstrated that a 1 min cooling period is necessary to achieve consistent seed size (Supplementary Figs. 14 and 15). This duration is considered the minimum time required to reach the temperature at which uniform seeds form when immersed in a dry-ice–acetone bath (−78 °C). To test the temperature threshold, samples were cooled to various temperatures (from −10 °C to −50 °C) for 5 min. Decreasing seed size with decreasing temperature was observed, which indicated that there was an increased nucleation efficiency at lower temperatures (Supplementary Figs. 16 and 17). The threshold for obtaining uniform seeds was found to be −50 °C, close to the glass transition temperature (Tg) of PCL. At this temperature, chain movement is extremely limited, causing neighbouring PCL blocks to nucleate rather than grow on preformed nuclei through chain movement. We suggest that sufficient cooling time is required to enable the solution to reach a supersaturated state in the nucleation zone. If not, only partial nucleation to seeds will be achieved, where remaining polymers may epitaxially grow on these seeds to form cylinders. These studies show that the formation of well-defined, uniform seeds requires heating followed by rapid cooling of the solution, to take it from an undersaturated state to a supersaturated state within the nucleation zone (Fig. 1b)26,27,28, resulting in fast spontaneous nucleation to uniform seeds. Based on the above results, flash-frozen seeds were optimally prepared at 0.1 mg ml−1 by heating the solution to 75 °C for 2 min followed by cooling for 1 min using a dry-ice–acetone bath.

To confirm that the flash-frozen seeds remained efficient for living CDSA, unimer addition was conducted according to our previous procedure (Fig. 1a)10,12,13. Similar results to the living CDSA using seeds prepared in a classical manner through sonication (Supplementary Figs. 18 and 19 and Supplementary Table 3) were obtained, with all seeds converting to platelets and the size of platelet increasing with the addition of more unimers (area, length and width increased from 0.11 μm2, 0.57 μm and 0.21 μm to 1.47 μm2, 2.46 μm and 0.66 μm respectively; Fig. 1e, Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21 and Supplementary Table 4). The linear relationship between the mass of the unimers and the area of the platelets (Supplementary Fig. 20d) indicates the controllable living behaviour was retained. This was further confirmed using fluorescent-dye-modified unimers in different aliquots, revealing platelets with layered structures, indicated using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM; Supplementary Fig. 22).

We further sought to quantify the nucleation efficiency of the flash-freezing approach; however, as DLS provides only particle size information, comparing the number of flash-frozen seeds was not feasible. Consequently, we hypothesized that using living CDSA using flash-frozen seeds prepared under different conditions, with the addition of unimers at a constant unimer-to-seed ratio of 10, would allow correlation between platelet size and seed number, such that a lower number of seeds results in larger platelets, while a higher seed content leads to smaller platelet sizes (Supplementary Figs. 23–30 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6). As anticipated, there was no evidence of remaining seeds after seeded growth, and the size of platelets decreased with an increasing heating time to prepare flash-frozen seeds and then reached a plateau (Supplementary Fig. 25), aligning with the observed trend in the size of flash-frozen seeds. In addition, smaller platelets were produced from flash-frozen seeds compared with those produced from classical seeds, indicating that flash-freezing is a more effective method for seed formation, a conclusion also supported by living CDSA with flash-frozen seeds prepared under different conditions (Supplementary Figs. 24–30).

To increase the scale of seed preparation, we attempted to increase the volume by fivefold in batch. However, owing to insufficient heat transfer at a larger scale (total mass of 1 mg) in batch, the obtained seeds exhibited high dispersity (Supplementary Figs. 31 and 32). Although uniform seeds were obtained after increasing the heating time, their size did not match that of the 0.2 mg control batch, which was previously prepared on a small scale, and the size of the platelets obtained after living CDSA was substantially larger (Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34).

Critically, seed preparation provides the biggest challenge to the scalability and reproducibility of precision nanoparticles by CDSA, due to the arduous process of preparing uniform seeds. Our previous work demonstrated the potential of flow reactors in CDSA living growth29 and therefore directed our attention to exploring the synthesis of seeds in a flow reactor, as reaction conditions can be kept constant and greater scale is achieved by scaling-out or through continuous production. The modularity of flow reactors allows flexible reactor design, connecting components with specific functions to the flow cascade as needed30,31. Importantly, the high surface area-to-volume ratio in these flow reactors facilitates excellent heat transfer and, therefore, enhances temperature control32,33, ensuring isothermal conditions and rapid, controllable cooling to achieve supersaturation, which is crucial for seed formation. Furthermore, we envisaged that integration of seed preparation with living CDSA, in a single continuous flow set-up will allow the direct preparation of platelets from polymers to streamline the end-to-end process, facilitating the direct transformation from polymers to platelets while retaining uniformity and circumventing potential issues of batch-to-batch variability.

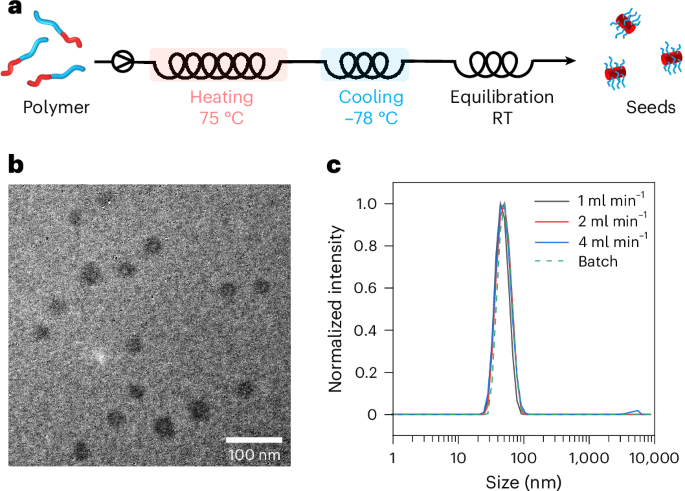

A flow reactor was established (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 35) with the in-series connection of a heating channel (2 ml) in an oil bath set at 75 °C, a cooling channel (1 ml) in a dry-ice–acetone bath and an equilibration channel at room temperature. The polymer solution was initially pumped through the flow reactor at 1 mg ml−1, with heating (2 min), cooling (1 min) and annealing (1 min) times optimized on the basis of batch conditions. The resulting seeds (20 mg, 46 nm; Fig. 2b,c and Supplementary Table 7) prepared in this manner closely resembled those prepared in the batch control (0.2 mg, 50 nm). Owing to the increased heat transfer in flow, we hypothesized that we could shorten the heating and cooling times to obtain more rapid seed synthesis while retaining the high quality. Thus, the flow rate was increased from 1 ml min−1 to 2 and 4 ml min−1 to give total residence times of 2 min and 1 min, respectively. TEM and DLS confirmed that the flash-frozen seeds prepared in flow maintained a consistent size and morphology with increasing flow rates, although some aggregates were observed at a flow rate of 4 ml min−1 (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 36 and Supplementary Table 7). Nevertheless, the throughput could be increased to 0.2 mg min−1 at the flow rate of 2 ml min−1, equivalent to the uninterrupted production efficiency of three batch reactors (0.067 mg min−1), irrespective of loading and unloading.

a, Preparation scheme. RT, room temperature. b, A TEM image of seeds prepared in flow at flow rate of 1 ml min−1. c, The DLS size distribution of flow seeds prepared at various flow rates and in batch. Samples were stained using 1 wt% uranyl acetate aqueous solution.

Source data

Living CDSA using flow flash-frozen seeds was initially investigated in a detached flow reactor. In this flow reactor (Supplementary Fig. 37a), to achieve good mixing, flash-frozen seeds were preheated to 30 °C, and epitaxial growth occurred after mixing with unimers29. Unexpected unimer self-nucleation was observed, which resulted in the formation of extremely large platelets (length >10 μm; Supplementary Fig. 37b). In addition, a notable number of the platelets were much larger than those prepared in batch that were grown from the same seeds. We suggest that this is a consequence of the combined influence of elevated temperature and shear force in flow, which causes some of the seeds to dissolve due to their low crystallinity. To avoid self-nucleation, the crystallization rate was decreased by halving the concentration in our previous work; however, this also decreases the throughput. Alternatively, to stabilize the seeds made from diblock polymer, a small amount of PCL homopolymer was introduced as an additive during the seed preparation process. PCL homopolymer was chosen due to its higher crystallization ability and melting point than the diblock copolymer, as well as its ability to cocrystallize with the diblock polymer.

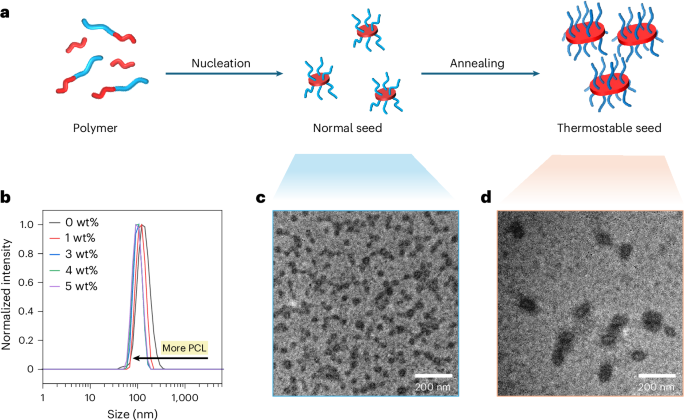

Flash-frozen seeds generated in flow containing various amounts of PCL (1–5 wt%) were prepared using an identical flow set-up (Supplementary Figs. 35 and 38a). All seed samples containing PCL were found to be of a similar size (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 38 and Supplementary Table 8). We propose that these seeds have a 2D structure, in line with previous work that has shown that adding PCL homopolymer to diblock copolymers during self-assembly induces a morphological transition from 1D to 2D (ref. 34). The temperature of the equilibration channel was then increased to 30 °C to anneal the seeds (Supplementary Fig. 39a), enhancing their thermal stability and initiation efficiency by promoting higher crystallinity, as shown in previous work35. This adjustment enables a more detailed analysis of seed morphologies immediately before mixing with unimers during living CDSA. As observed in TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 39b), all annealed samples showed similar morphology, and the sizes of the thermostable seeds measured by DLS decreased as more homopolymers were added (Fig. 3b). To demonstrate that some seeds were dissolved as they passed through the annealing channel, these seed samples aged for 3 days, and the sizes of the seeds were measured using DLS (Supplementary Fig. 40 and Supplementary Table 9). The size of the seeds without PCL increased gradually with the extension of ageing time (Supplementary Fig. 40f), and a short cylindrical morphology was obtained after 3 days of ageing (Supplementary Fig. 40a), on account of the redissolved unimers growing on the surviving seeds36,37. A similar trend occurred in the sample with 1 wt% PCL (Supplementary Fig. 40b); however, with a PCL content increased to 3 wt% or higher, the seed samples were stable, and similar morphologies before and after ageing were observed, as shown by TEM images (Supplementary Fig. 40c–e).

a, Mechanism of preparing robust seeds. b, DLS size distribution of robust seeds with various PCL contents. c, A TEM image of seeds prepared by the mixture of PCL (3 wt%) and diblock copolymer (PCL-b-PDMA) before annealing. d, A TEM image of robust seeds prepared by the mixture of PCL (3 wt%) and diblock copolymer (PCL-b-PDMA) after annealing. Samples were stained using 1 wt% uranyl acetate aqueous solution.

Source data

Flow flash-frozen seeds with various PCL contents were used to conduct living CDSA with 10 equiv. unimers to show how PCL content influences the behaviour of epitaxial growth of the flash-frozen seeds (Supplementary Fig. 37). The results indicated that self-nucleation can be avoided once PCL was involved in the seed preparation, and the size of the obtained platelets decreased as more PCL was used to prepare flash-frozen seeds (Supplementary Fig. 37 and Supplementary Table 10). The results were in line with the stability trend of flash-frozen seeds (Supplementary Fig. 41). As PCL increased the stability of seeds, more seeds survived after preheating; thus, each seed shared fewer unimers, resulting in smaller platelets.

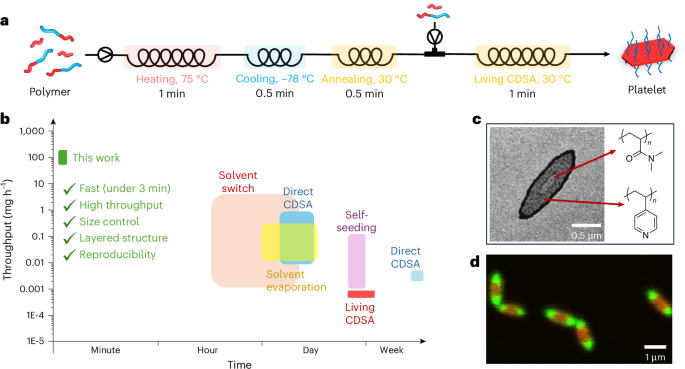

After optimizing seed preparation and living CDSA in flow, a flow reactor cascade was developed to prepare size-controllable platelets directly from polymers (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 42). It should be noted that, to combine the two sections and push the productivity as high as possible, the flow rate in the flow cascade was conducted at 1 ml min−1, which is faster than that applied for the separate living CDSA process. In addition, the throughput was further enhanced by increasing concentration. Typically, flash-frozen seeds are prepared at 0.1 mg ml−1 in flow, while traditional batch living CDSA is performed at a seed concentration of 0.01 mg ml−1. Challenges arise as a higher concentration contributes to a faster crystallization rate, which increases the burden on the short mixing time to achieve a homogeneous system to grow uniform platelets. To solve this problem, a reverse T micromixer and folding tubing were applied to increase mixing by creating turbulence in flow (Supplementary Figs. 35 and 42). The practicality of both strategies has been demonstrated in the literature20,38,39.

a, Preparation scheme of platelets prepared in 3 min. b, A comparison of processing time and throughput of reported 2D PCL-based platelets in the literature10,11,12,13,14,34,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72. c, Double-layered platelets with heterogeneous coronas. d, CLSM image of layered platelets with tunable core chemistry.

Source data

Fast preparation and high throughput can be achieved simultaneously using this integral flow cascade. By controlling the flow rates, platelets of controllable size can be prepared in 6 min through a continuous end-to-end manner (Supplementary Table 11). The platelets obtained through this flow process are uniform (Supplementary Fig. 43 and Supplementary Table 12), and the area of platelets exhibits a linear relationship with the mass of the unimers (Supplementary Fig. 43d). Alternatively, the dimensions of the platelets can be adjusted using the self-seeding strategy by fixing the unimer-to-seed ratio and varying the annealing temperature (Supplementary Tables 13 and 14 and Supplementary Fig. 44). However, the size control achieved with this method is not as precise as that in the seeded growth approach, which adjusts the amount of added unimers. To demonstrate the facile nature of expanding this reactor cascade, another reactor was added to allow the production of multilayered fluorescent platelets (Supplementary Fig. 45). To further increase the throughput, the total flow rate was increased to 2 ml min−1, which is based on the successful seed preparation at this flow rate. As we expected, uniform platelets can still be obtained at the increased flow rate (Supplementary Fig. 46), and these platelets are of an even higher uniformity owing to better mixing at higher flow rates. Therefore, the timescale to prepare platelets from polymers was reduced to 3 min, and the throughput increased to 2.2 mg min−1 (132 mg h−1).

For comparison, we summarized the timescale and throughput of the production of the reported PCL-based platelets and platelets of other core chemistries (poly(ferrocenyldimethylsilane)2,40, poly(l-lactide) (PLLA)41 and conjugated polymers42,43) prepared by living CDSA (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 47). Our work demonstrates an efficient method for preparing size-controllable platelets through CDSA, with a significant reduction in processing timescale (>240 times) and improvement in throughput (>60 times) compared with previous works. Compared with PI-CDSA, another scale-up strategy for CDSA, our flow method offers superior size control and reproducibility16,17,18. The high efficiency was achieved through excellent heat transfer in the flow cascade for seed preparation, combined with ideal mixing and the fast crystallization rate induced by high concentration.

To demonstrate the scope and potential of the flow cascade technique, we used PCL-based polymers with various chemistries to synthesize functional and complex platelets. Double-layered platelets with different corona chemistries were prepared using the integrated flow cascade, with two living CDSA modules connected in series (Supplementary Table 15). Due to the different stain adsorption capacities of coronas, platelets with heterogeneous coronas exhibited different patterns after staining (Supplementary Fig. 48). In addition to tuning the corona chemistry, the core chemistry was also modified using fluorescent -dye-labelled PCLs. By leveraging the differences in crystallization rates of PCLs with different molecular weights, various fluorescent patterns were prepared (Supplementary Table 16 and Supplementary Fig. 49). These patterns can be further tuned by easily adjusting the relative flow rates in a four-way flow cascade (Supplementary Fig. 49a).

Building on this, we extended our method to PLLA-based polymers (Supplementary Figs. 50–53 and Supplementary Tables 17 and 18), which are also biocompatible and biodegradable, but it has proven challenging to obtain dimensional control over them in CDSA6,41,44,45,46. Using the same flow set-up, we synthesized PLLA-based rhombic platelets with tunable sizes through living CDSA (Supplementary Fig. 54 and Supplementary Table 19). This method’s ability to control the platelet size in PLLA block polymers via seeded growth showcases its versatility, precision and scalability. The ability to fine-tune platelet dimensions highlights the broad applicability of our approach and its potential for advancing precision polymer self-assembly. Overall, these results underscore the unique advantages of our technique, offering a powerful, scalable and precise method for developing diverse and complex nanostructures.

Conclusions

This study presents an advance in polymer nanoparticle preparation via CDSA by integrating seed formation and living growth within a flow cascade reactor. This integration reduces the processing time from a week to 3 min and improves the throughput to 132 mg h−1, surpassing other methods by orders of magnitude. The use of flash-freezing for seed preparation shortens batch processing times, with potential benefits for other CDSA systems to enhance efficiency. By optimizing experimental parameters and utilizing a modular reactor design, this study seamlessly integrates CDSA and flow synthesis, enabling the rapid, controlled production of uniform anisotropic polymer nanoparticles. Overall, this advance opens possibilities for programmable material design, allowing precise control over nanostructure properties and marking a meaningful step forward in high-throughput polymer nanomaterial synthesis.

Methods

Preparation of homopolymer

Homopolymers were prepared by ring-opening polymerization in a glovebox filled with N2. ε-Caprolactone (2.246 g, 19.68 mmol), diphenylphosphate (70.33 mg, 0.28 mmol), 2-cyano-5-hydroxypentan-2-yl-ethyl carbonotrithioate (70 mg, 0.28 mmol) and toluene (19.726 ml) were charged into a 50 ml round-bottom flask. The mixture was stirred at room temperature, and 1H NMR spectroscopy was used for monitoring. After approximately 6.5 h, the reaction was quenched using AmberLyst agent, and the solution was removed from the glovebox. The product was purified by precipitation three times in cold diethyl ether and collected through centrifugation. A yield of 1.42 g (monomer conversion 71%) of light-yellow solid was obtained after thorough drying in a vacuum oven.

Preparation of diblock polymer

PCL-b-PDMA was prepared by chain extension of PCL homopolymer. Here, PCL50 (100 mg, 0.0168 mmol), N,N-dimethyl acrylamide (400 mg, 4.03 mmol), 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionitrile) (0.276 mg, 0.00168 mmol, 10 mg ml−1 in dioxane) and dioxane (1 ml) were added into an ampoule. Before immersion in an oil bath set at 70 °C, the solution was freeze-pump-thawed three times. After 2 h, polymerization was quenched by immersing the ampoule in the liquid N2. Once it reached room temperature, the crude product was precipitated three times into the cold diethyl ether and collected by centrifugation. Then, 428 mg (monomer conversion 88%) of a solid was obtained after thoroughly drying in the vacuum oven.

Flash-frozen seeds prepared in batch reactors

Typically, batch preparation of flash-frozen seeds was carried out in a 7 ml vial with the polymer concentration maintained at 0.1 mg ml−1. Specifically, 4 μl of PCL-b-PDMA stock solution (50 mg ml−1 in tetrahydrofuran) was introduced into 2 ml of ethanol. The mixture was heated to 75 °C for a specified duration (1–60 min) and then rapidly cooled by immersion into a dry-ice–acetone bath (or ice bath and natural cooling) for several minutes (1–5 min). The resulting seed micelles were obtained after equilibration to room temperature. Seed samples of different concentrations were prepared by tuning the addition of PCL-b-PDMA stock solution.

Flash-frozen seeds prepared in flow reactors

The flow reactor was set up as shown in Supplementary Fig. 35. A high-performance liquid chromatography pump (Jasco PU-980) was connected to a steel coil (inner diameter 0.75 mm, 2 ml), which was immersed in an oil bath set at 75 °C. A polytetrafluoroethylene tubing (inner diameter 0.5 mm, 2 ml) was connected downstream of the heating component, of which a winding component (0.5 ml) and a coil (0.5 ml) was controlled at −78 °C using a dry-ice–acetone bath, and the following equilibration coil (1 ml) was set at room temperature. The winding tubing, designed to enhance mixing in flow, was created by winding polytetrafluoroethylene tubing in an S shape around the tip holder (SureOne Pipet Tips, Fisher).The diblock polymer solution (PCL-b-PDMA, 0.1 mg ml−1 in ethanol), prepared as described, was injected by the high-performance liquid chromatography pump at various flow rates (1, 2 and 4 ml min−1), and steady samples were collected after passing 12 ml polymer solution (three times the reactor volumes).

Continuous end-to-end preparation of platelets in flow

The integral flow cascade to prepare platelets from polymers directly is shown in Supplementary Fig. 42. The polymer solution (PCL/PCL-b-PDMA = 3/97 (wt%), 0.1 mg ml−1 in ethanol) was initially pumped into a steel coil (inner diameter 0.75 mm, 2 ml) set at 75 °C and then passed through the cooling channel set at −78 °C, which included winding (inner diameter 0.5 mm, 0.5 ml) and coil (inner diameter 0.5 mm, 0.5 ml) parts. After passing through the annealing channel at 30 °C (inner diameter 0.5 mm, 1 ml), the seed solution was mixed with unimers in a reverse T micromixer. An ageing channel was set downstream, which included a winding tubing (inner diameter 0.5 mm, 0.5 ml) followed by a coil (inner diameter 0.5 mm, 1.5 ml). Platelets were collected from the outlet. The self-seeding strategy was conducted to tune the size of platelets by setting the annealing channel at various temperatures (28, 30, 32 and 34 °C) and fixing a unimer-to-seed ratio of 10 (Supplementary Fig. 44a). To prepare layered platelets, another reverse T mixer and ageing channel was connected downstream. To prepare platelets with tunable core chemistry, the reverse T micromixer was replaced by a four-way cross micromixer (Supplementary Fig. 49a).

Responses