Discordance between a deep learning model and clinical-grade variant pathogenicity classification in a rare disease cohort

Introduction

The diagnostic yield of whole-genome and exome sequencing (WGS and WES) for rare Mendelian diseases remains below 25%6,7. With 30 million genomes sequenced globally, there is a clear and unmet need for scalable interpretation of genetic variants for pathogenicity classification. This is particularly true for the numerous missense variants that continue to be categorized as variants of uncertain significance (VUS)8. Over the past decade, many researchers have turned to artificial intelligence (AI) to address this challenge. AI enables systems to perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as pattern recognition and decision-making. Within AI, machine learning (ML) focuses on building predictive models by identifying patterns in data. Deep learning, a specialized subset of ML, employs multilayer neural networks to extract complex features from large datasets9. These methods excel in image recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition. A prominent deep learning architecture is the Transformer10, which leverages self-attention mechanisms to efficiently process sequence data. By capturing long-range relationships among elements, Transformers have proven especially useful in analyzing DNA, RNA, and protein sequences11. Notably, Transformer-based models like the Evoformer used in AlphaFold have revolutionized protein structure prediction12. This milestone underscores the profound impact AI can have on genomics.

Despite significant advancements in deep learning methods3,4,5, current predictions often fall short of accurately predicting the pathogenicity of these mutations at scale13. These shortcomings are largely attributed to two factors: (1) the scarcity of gold-standard labeled datasets, and (2) the omission of genotype-phenotype associations during model training. Here, we aim to evaluate the performance and utility of the recently published deep learning model AlphaMissense (AM)5, specifically focusing on its ability to identify pathogenic and likely pathogenic missense variants of clinical significance in well-phenotyped individuals within a rare disease cohort14,15. First, we examine agreement between missense variants identified as likely pathogenic by AM (AM_LP) and those expertly curated as pathogenic and likely pathogenic in ClinVar (ClinVar_P and ClinVar_LP, respectively)8, within a cohort of 7454 individuals with rare diseases and their family members. This cohort comprises 3383 patients with rare diseases presumed to be of genetic origin, along with their family members, including those with early and very early onset inflammatory bowel disease, sensory neural hearing loss, epilepsy, and more than 45 rare conditions as previously described14,15.

Results

By comparing AM’s classification of missense variants with expert-curated data from ClinVar8, we estimate the precision and recall. This analysis addresses the disparity between the balanced distribution of pathogenic and benign variants in gold-standard datasets, which are used for algorithm fine-tuning, and the rarer occurrence of pathogenic variants in real-world datasets. Subsequently, we conducted a comparative analysis of AM’s performance against other deep-learning approaches, such as ESM1b4 and EVE3, as well as against an established non-deep learning method, the rare exome variant ensemble learner (REVEL)16 and deleteriousness meta-score BayesDel17. ESM1b and EVE were selected for comparison with AM because they utilize deep learning algorithms and demonstrated similar top performances in Cheung et al.’s study5. EVE employs an unsupervised generative autoencoder, showcasing superior performance for a limited set of well-aligned proteins and residues. In contrast, ESM1b covers entire protein-coding genes by pre-training protein language models with samples across all organisms, thus providing scores for regions not covered by multiple sequencing alignments. REVEL and BayesDel were selected for comparison with AM because these tools have been integrated into gene-specific American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) guidelines developed by various Variant Curation Expert Panels within ClinGen18,19,20,21. Moreover, both tools showed overall superior performance in clinical variant classification compared to other non-deep learning methods22. Coverage across human protein-coding genes differs among these methods as per dbNFSP v4.6. EVE assesses 2895 genes, ESM1b evaluates 19,027 genes, REVEL and BayesDel cover 18,289 and 18,991 genes, respectively, and AM includes 18,985 genes (Fig. 1a). Excluding EVE, which has smaller coverage, AM, BayesDel, ESM1b, and REVEL share 16,803 genes with variants reported in ClinVar in common (Supplementary Fig. 1). Our analysis, focused on evaluating AM’s precision, is constrained by the intersection of AM’s gene coverage and expertly curated variants in ClinVar, opting not to undertake a comprehensive benchmark across all deep learning methods.

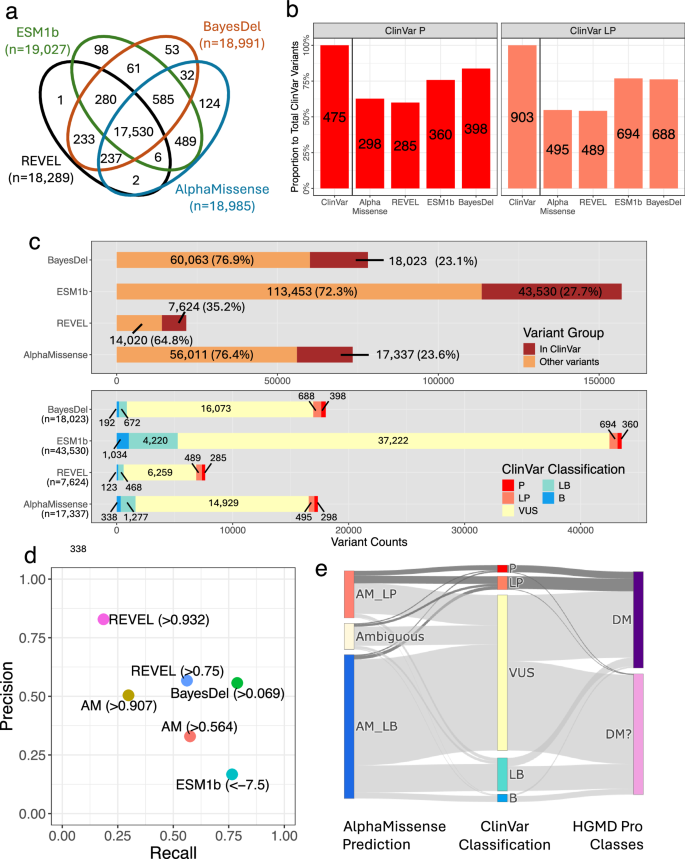

a Gene coverage comparison across missense variant effect prediction methods (VEPs). A total of 17,530 genes are covered by the four VEPs, and variants in these genes serve as targets for further analysis. b Counts of likely pathogenic variants predicted by AlphaMissense (> 0.567), REVEL (> 0.75), ESM1b (< –7.5), and BayesDel (> 0.0692655) among ClinVar pathogenic (ClinVar_P) and likely pathogenic (ClinVar_LP) variants in the cohort. The y-axis represents the proportion of total ClinVar_P (N = 475) or ClinVar_LP (N = 903) variants found in the cohort. Numeric labels indicate variant counts for each category and method. c Counts and proportions of variants reported in ClinVar among all variants classified as likely pathogenic by each method (top panel). Stratification of variants classified as likely pathogenic by each method according to their ClinVar classifications (bottom panel). d Precision and recall metrics for each prediction method (AM AlphaMissense). e Discrepancies for variants discovered in our cohort that are also annotated in both HGMD Professional (DM and DM? classes) and ClinVar, comparing AlphaMissense predictions with the classifications provided by these databases.

Identifying phenotype-associated variants in individuals with rare diseases is a two-step process: first, by predicting and classifying variant effects, and subsequently, by prioritizing these variants within genes linked to presenting phenotypes23 (Supplementary Fig. 2). The lack of phenotype information in the development (or fine-tuning) of AM and other prediction algorithms required a comparison of AM’s pathogenicity scores with ClinVar’s pathogenicity classifications within our well-phenotyped patient cohort. AM identified 298 of 475 ClinVar_P (62.7%) and 495 of 903 ClinVar_LP (54.8%) variants were classified as AM_LP (Fig. 1b). Conversely, 17,337 (23.6% of total rare variants classified as AM_LP, n = 73,348, gnomAD minor allele frequency < 1%) variants were also reported in ClinVar, regardless of reported pathogenicity (Fig. 1c top panel). Of these, only 298 (1.7% of 17,337) and 495 (2.9% of 17,337) were annotated as ClinVar_P and ClinVar_LP, respectively (Fig. 1c bottom panel). Most variants were reported as VUS. Among the 17,337 variants, 338 (1.9%) and 1277 (7.4%) variants were benign or likely benign, respectively, in ClinVar. Similarly, REVEL, one of the leading non-deep learning methods, identified 7624 ClinVar variants above a threshold of 0.75. Among these, 285 (3.7%) were ClinVar_P, and 489 (6.4%) were ClinVar_LP. BayesDel evaluated a comparable number (18,023) at a threshold of 0.0692655, detecting 398 (2.2%) ClinVar_P and 688 (3.8%) ClinVar_LP.

One unique feature of AM is its threshold for classifying variants as likely benign (scores of 0.34 or below). In our cohort, 83 of 475 ClinVar_P variants (17.5%) and 223 of 903 ClinVar_LP variants (24.7%) met this criterion. Some misclassifications by AM and other methods—ClinVar_P and ClinVar_LP variants not predicted as likely pathogenic—may be attributed to splice site effects rather than missense changes. Indeed, all four methods tended to assign lower pathogenicity scores to variants predicted to disrupt splice sites, as identified by MaxEntScan and SpliceAI (Supplementary Fig. 3). A total of 5–7% of ClinVar_P and ClinVar_LP missense variants not classified as likely pathogenic by these algorithms were found to potentially affect splice sites, including 6 of 83 ClinVar_P and 12 of 223 ClinVar_LP variants. Precision and recall for rare missense variants discovered in our cohort and also curated in ClinVar for AM, REVEL, BayesDel, and ESM1b are detailed in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 1. AM’s performance on ClinVar_P and ClinVar_LP variants showed a preference for recall over precision at the author-recommended threshold of 0.564. Raising the threshold to 0.907 increased precision but reduced recall.

After assessing AM’s classifications against the current gold standard, ClinVar, and other algorithms, we expanded our analysis to include discrepancies among expert-curated databases as well as their alignment with AM within our cohort. The comparison of the disease-causing mutation (DM) and likely disease-causing mutation (DM?) categories from the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) Professional24 (release Q1-2023) with ClinVar’s annotations showed limited agreement25. Specifically, the DM and DM? categories from HGMD aligned with ClinVar’s P or LP classification at rates of 27.0% and 1.5%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 4). In contrast, AM classified 55.8% of DM and 74.4% of DM? classifications from HGMD as likely benign (AM_LB), most of which were classified as VUS, LB, or B in ClinVar. Despite these differences, the majority of variants classified as ClinVar_P and _LP were closely aligned with HGMD’s DM and DM? categories and classified as likely pathogenic by AM (Fig. 1e). These observations highlight the critical importance of expert consensus in accurately classifying variant pathogenicity and shed light on the complexities involved in interpreting missense variants for rare diseases. Genomic variant classification is not static; it evolves over time as ClinVar and HGMD continually work to reclassify variants and improve pathogenicity classification25. These efforts are mostly supported by population-scale genomic variant datasets and expert curation panels. While deep learning-based algorithms have the potential to aid in this process, our findings suggest that AM, though advanced, requires further development to effectively address these challenges.

Next, we concentrate on rare diseases with consensus candidate genes to demonstrate the practical utility of AM in prioritizing clinically meaningful genetic variants. We assessed AM’s performance within a cohort diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), specifically those with very early onset (less than 6 years of age at IBD onset) and early onset (less than 10 years of age at IBD onset). This population was selected based on the increased likelihood of monogenic disease (i.e., monogenic IBD (mIBD)) and the availability of expert-curated candidate genes for mIBD26. Notably, a ClinGen Expert Panel for IBD has not yet been established. For most of these genes, the primary phenotypes associated with pathogenic variants—as reported in ClinVar—include primary immunodeficiencies and epithelial barrier defects, which can manifest as mIBD. In these cases, precision therapies targeting the underlying immune defect, where available, can treat the mIBD, which may be refractory to conventional IBD therapies27,28,29. Subjects are a prospectively enrolled, broadly consented, WES sequenced cohort of 750 patients with IBD at a large pediatric teaching hospital (“Methods”)14. All genomic variants with allele frequency below 1% in gnomAD were selected for further evaluation, as mIBD is considered a rare condition. Also, given that AM’s author-recommended default threshold emphasizes recall over precision, we calibrated the threshold for classifying variants as likely pathogenic to achieve a higher estimated positive predictive value using methods suggested by ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group30. For AM_LP, a threshold of 0.907 was used to achieve a 0.98 posterior probability of pathogenicity (described in the “Methods” section). For each individual diagnosed with IBD, we prioritized potentially disease-associated genetic variants within a consensus list of 102 mIBD genes (Supplementary Table 2), in the order of loss-of-function (LoF), ClinVar_P, ClinVar_LP, and AM_LP (Fig. 2a left panel and Supplementary Table 3)31. We identified LoF variants in 77 (10.3% of 750) patients and ClinVar_P or _LP variants in 34 (4.5% of 750) patients, including 16 with LoF variants as well. In total, 95 patients (12.7% of 750) possessed genetic variants that require further validation and interpretation, before considering AM_LP variants.

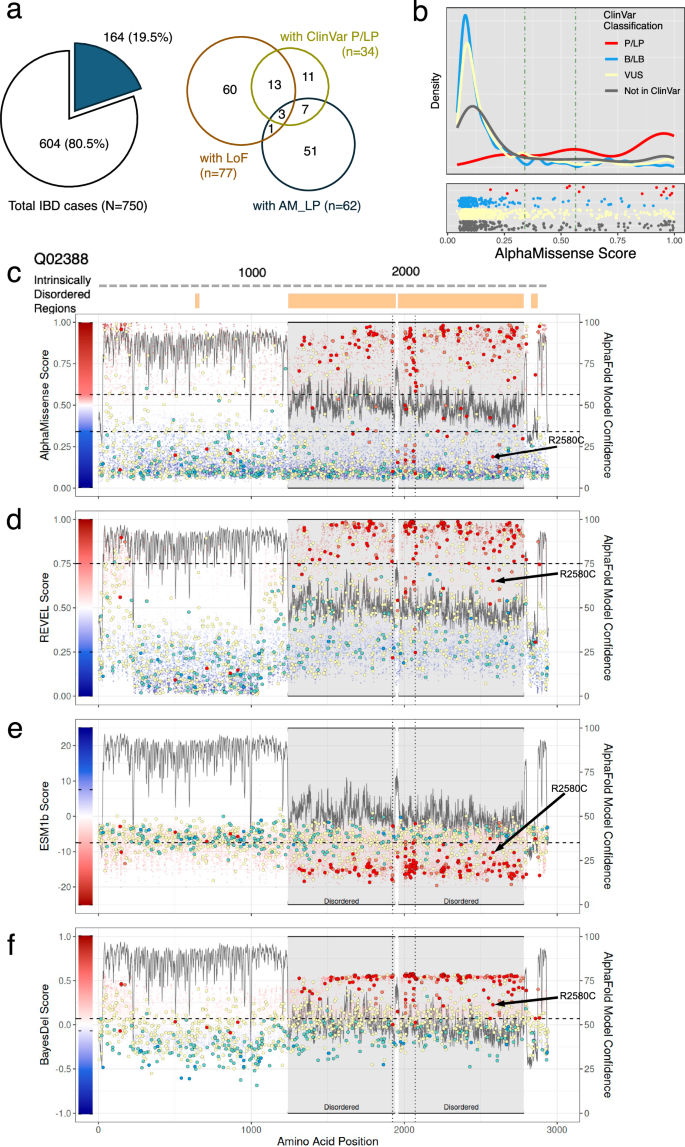

a Number and proportion of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) in the cohort carrying loss-of-function (LoF) variants, ClinVar pathogenic (ClinVar_P) or likely pathogenic (ClinVar_LP) variants, or variants predicted as likely pathogenic by AlphaMissense (left panel). Composition of patients according to the combination of these variants found in each individual (right panel). b Distribution of AlphaMissense pathogenicity scores for ClinVar variants and other missense variants in candidate genes. Vertical lines indicate the thresholds for likely benign (0.34) and likely pathogenic (0.564) classifications by AlphaMissense. c–f Each panel corresponds to a different prediction method: c AlphaMissense, d REVEL, e ESM1b, and f BayesDel. The experimentally validated protein domain structure of COL7A1 (UniProt accession number: Q02388) is shown, with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) indicated by orange boxes at the top. Pathogenicity scores along amino acid positions are plotted as colored dots, with color scales reflecting each method’s scoring system. ClinVar pathogenic and likely pathogenic variants are marked with red and salmon circles, respectively. Notably, many of these variants are frequently misclassified as likely benign, especially in IDRs (gray highlight), where the AlphaFold2 model confidence score (pLDDT) is below 50. A black arrow points to a misclassified pathogenic variant found in our cohort by AM.

A total of 62 patients (8.3% of 750) had a median of one AM_LP variant (range 1–2) within the 102 candidate genes, with various combinations of LoF or ClinVar variants (Fig. 2a right panel and Supplementary Table 4). Of the 48 variants found in these 62 patients, five (10.4%) had findings also supported by ClinVar as P or LP. Except for the 20 variants that were not reported in ClinVar, the rest of AM_LP variants were either reported as VUS (n = 20), ClinVar_B (n = 1), or reported as pathogenic but without criteria specified (n = 2). Out of the 62 patients, 4 had both LoF and AM_LP variants within the candidate genes. An interesting case to illustrate involved a patient with congenital enteropathy and ocular and gonadal abnormalities who exhibited a compound heterozygous variant in the WNT2B gene. The maternally inherited frameshift variant was reported as VUS in ClinVar. The presumably paternally inherited missense variant, NM_024494.3(WNT2B):c.722G>A (p.Gly241Asp) was classified as AM_LP (Supplementary Fig. 5). Indeed, all computational algorithms–AM, BayesDel, ESM1b, and REVEL–predicted this missense variant as likely pathogenic. This case, along with two others, has been reported as part of an oculo-intestinal syndrome attributed to genetic variants in the WNT2B gene32. In clinical genetics practice, LoF variants are generally prioritized over missense variants, except when the same amino acid change has already been established as a pathogenic mechanism33. Excluding the 4 cases with LoF variants and the 7 cases with ClinVar_P/LP variants, there were 51 cases (6.8% of 750, Fig. 2a right panel) presented AM_LP variants, averaging one variant per case within the same set of 102 candidate genes, which could be considered for further evaluation depending on their zygosity. This suggests the potential utility of AM’s pathogenicity scores in elucidating the putative genetic basis for additional cases. Nonetheless, functional studies and additional evaluations are crucial to confirm the pathogenicity of these variants for mIBD. Upon closer examination of the ClinVar_P/LP variants identified in IBD cases, some failed to meet the threshold for classification as AM_LP within the 102 candidate genes (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 4), but that did not imply all of them were misclassified. Fifteen missense variants were classified as P or LP in ClinVar, eight of which scored below the threshold of 0.907, including five with scores less than 0.564, the threshold originally suggested by Cheung et al.’s5. Among these, three ClinVar_P variants had scores below 0.34, placing them in the likely benign category according to AM. Interestingly, all three were correctly classified as pathogenic by ESM1b and BayesDel, with no predicted splice-disrupting effects (Supplementary Table 5).

Intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) are protein segments lacking an ordered three-dimensional structure, facilitating versatile molecular interactions34. Interestingly, some of the discordant variants between ClinVar and AM were found to be located within IDRs35. For instance, the COL7A1 gene, encoding type VII collagen (UniProt accession number: Q02388), encodes 2944 amino acids (aa), where two non-collagenous domains (1–1240 aa and 2880–2930 aa) flank a collagenous domain (1240–2880 aa). Notably, the collagenous domain includes an intrinsically disordered hinge region (indicated as disordered in Fig. 2c). IDRs typically show the per-residue model confidence score (pLDDT), a measure of local accuracy according to AlphaFold2, below 50, as shown with the gray line in Fig. 2c12. Indeed, the same region showed an increased number of variants where ClinVar_P/LP variants were not classified as AM_LP (Fig. 2c). Interestingly, the other prediction algorithms showed variable performance in IDRs. For the pathogenic COL7A1 variant NM_000094.4:c.7738C>T (NP_000085.1:p.2580R>C; R2580C, black arrow in Fig. 2c), AM classified it as likely benign, assigning a pathogenicity score of 0.189 (Supplementary Table 3). REVEL, meanwhile, gave this variant a score of 0.653, which falls below its pathogenic threshold of 0.75 (Fig. 2d). In contrast, ESM1b and BayesDel correctly predicted the same variant as pathogenic (Fig. 2e, f). Notably, the number of misclassified variants in the IDRs of COL7A1 differed among the various algorithms.

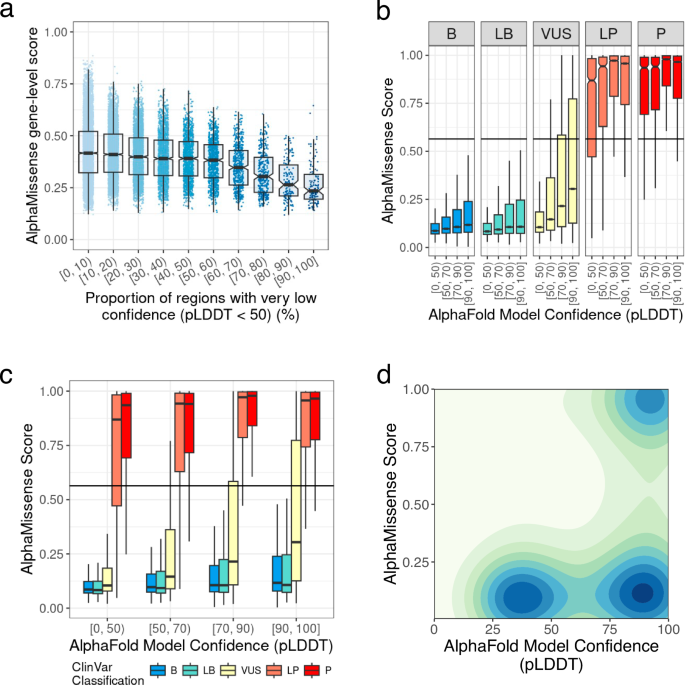

Considering that AlphaFold2’s predicted three-dimensional structures were used to pre-train AM’s deep learning models, we suspected that regions predicted with low confidence by AlphaFold2 would correspond to areas with generally lower AM pathogenicity scores, leading to discordance with ClinVar’s P/LP classifications. For this analysis, we examined all protein-coding genes with AM pathogenicity scores (n = 19,084). AM’s gene-level scores are calculated by averaging all possible AM pathogenicity scores for each gene. Indeed, AM gene-level scores were negatively correlated with the proportion of very low confidence (pLDDT < 50) (Fig. 3a). At the variant level, AM pathogenicity scores exhibited a negative correlation with pLDDT scores (Fig. 3b), and discrepancy between ClinVar_P/LP and AM_LP classifications was significantly greater for variants found in regions with pLDDT < 50 (Fig. 3c). Furthermore, AM pathogenicity scores for variants in the regions with pLDDT scores below 50 were significantly reduced regardless of their classification in ClinVar (Fig. 3d and Supplementary Fig. 6), leading to increased discrepancies with ClinVar classifications and inaccurate gene-level essentiality scores. These findings underscore the challenges AM faces in accurately predicting the impact of missense variants in certain regions and genes. We further expanded our analysis across all genes and variants in our study to systematically evaluate performance in IDRs. At the gene level, similar trends were observed across different algorithms (Supplementary Figs. 7–9, panel a). At the variant level, REVEL demonstrated difficulties predicting pathogenicity in IDRs, whereas BayesDel and ESM1b did not exhibit such issues. Interestingly, BayesDel’s performance did not seem to be affected by whether variants were located in IDRs. A comprehensive assessment of the performance of variant effect prediction algorithms in IDRs warrants further investigation.

a AlphaMissense (AM) gene-level scores, calculated by averaging AM pathogenicity scores for each gene, show an inverse correlation with the proportion of very low model confidence regions (pLDDT < 50) in each gene as determined by AlphaFold2. The proportion of regions with pLDDT < 50 is grouped by deciles. b Correlation between variant-level AM pathogenicity scores and AlphaFold2 per-residue model confidence across different ClinVar classes. The horizontal line marks AM’s threshold for likely pathogenic variants (0.564). c Distribution of AM pathogenicity scores as a function of per-residue pLDDT for various ClinVar classes. The horizontal line denotes AM’s threshold for likely pathogenic variants (0.564). d Two-dimensional density plot of AM pathogenicity scores for all ClinVar variants in the study.

Discussion

Deep learning models demonstrate state-of-the-art performance across a wide range of biomedical fields1,2. However, hasty adoption of such models could pose risks, as exemplified by the failure of a sepsis prediction algorithm, which produced a substantial number of false positives and false negatives within an electronic health record system36. This underscores the critical need for thorough evaluation before integrating deep learning-based algorithms into clinical and research workflows37. In summary, we found that there was significant discordance between pathogenicity predictions derived from a novel deep-learning model and those provided by ClinVar, particularly for variants located in IDRs and for intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs). Furthermore, clinical genetics prioritizes precision over recall due to the challenge of assessing numerous genomic variants per individual38. In contrast, computational algorithms tend to prioritize recall over precision, resulting in a larger number of false positives when identifying genetic variants in individuals with rare diseases without knowledge of candidate genes. Although the threshold can be adjusted to balance precision and recall, fine-tuning deep learning models must reflect the expected proportions of pathogenic and benign variants in an individual genome and incorporate reported phenotype information for genes and variants. This is crucial, as pathogenic variants are few and have incomplete penetrance compared to the many rare variants in an individual. This study is limited by its partial focus on a disease cohort from a single center and relying solely on ClinVar for assessing the clinical significance of variants. The integration of deep learning algorithms into clinical genetics workflows requires careful evaluation of potentials for false positive and false negative findings. Comprehensive studies that integrate detailed phenotype information with genotype data are crucial for advancing prediction algorithms beyond the current capabilities of ClinVar, thereby enhancing the application of these algorithms in clinical genetics.

Methods

Ethics statement

This study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at the authors’ institutions under protocol number P00000159.

A cohort of individuals diagnosed with rare diseases

The analysis focuses on a cohort of 7454 individuals, comprising 3383 individuals diagnosed with a spectrum of rare diseases, along with their family members. This group was enrolled through the efforts of 51 clinicians at Boston Children’s Hospital, motivated by clinical presentations that hinted at genetic underpinnings. All participants provided written or electronically signed informed consent, with those under 18 years old doing so through their parents or legal guardians, and those over 18 years old providing consent themselves. For comprehensive details on the project investigators, the main reasons for enrollment, and the genetic testing methods employed, refer to the project homepage (https://www.childrenshospital.org/crdc). Clinicians recorded phenotypes in RedCap, and the human phenotype ontology (HPO) terms were aligned with electronic health record extracts by CliniThink. The analysis utilized HPO terms and the primary diagnoses made by clinicians. The three most common diagnoses within the cohort were epilepsy (n = 1723), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) (n = 1430), and congenital sensory neural hearing loss (n = 842).

WES dataset and annotation of genomic variants

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) data were uniformly generated by a single vendor, utilizing the same exome capture kit across all samples. The processing of the WES data was carried out on the DRAGEN Bio-IT Platform germline workflow (v3.9). A merged variant call file (VCF) served as the basis for the current study. These variants were then annotated using the Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) release 110 to calculate functional consequences for 61,552 Ensembl genes, along with variant allele frequencies from the gnomAD database (release 3.0, gnomAD genomes). In addition to functional consequences, we extracted clinical significances, reviewed statuses, and the disease name for each variant in ClinVar (ClinVar 20231209) and mutation category for the variants in the Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD Professional, Q1-2023 release) to annotate variants in WES data. Finally, for each missense variant found in WES data, we extracted the pathogenicity scores for the matching variant and transcript from AlphaMissense (available at https://zenodo.org/records/8208688, scores of the variants in hg38 coordinates for 19,233 canonical transcripts only) and ESM1b (available at https://huggingface.co/spaces/ntranoslab/esm_variants, scores of all possible single amino acid change for 42,286 human isoforms). For pathogenicity scores from REVEL and BayesDel, we extracted scores compiled in dbNSFP v4.6.

MaxEntScan39 and SpliceAI40 were used to estimate variants’ effect on the splice site. Variants were assessed for native splice loss according to the flow described in Shamsani et al.’s39. Independently, variants with SpliceAI’s delta score greater than 0.5 (author recommended threshold) for acceptor gain, acceptor loss, donor gain, or donor loss were also considered splice disrupting.

Prioritizing variants for further clinical evaluation in inflammatory bowel disease cohort

For analysis of inflammatory bowel disease cases, candidate variants were selected by the following two steps. First, as monogenic inflammatory bowel disease is a rare condition, we only considered variants with a variant allele frequency of 1% or less in gnomAD genomes (version 3) in any of five population groups as identified among gnomAD genomes: nfe (non-Finnish European), amr (Admixed American), eas (East Asian), sas (South Asian), and afr (African/African American). Then, we selected (1) variants whose functional consequences can be considered as loss of protein function (LoF), (2) variants that were reported as pathogenic or likely pathogenic in ClinVar (ClinVar 20231209), or (3) missense variants that were classified as ‘likely pathogenic’ by AlphaMissense (AM_LP).

Specifically, variants were considered as LoF if their functional consequences were one of the following terms in Sequence Ontology: frameshift_variant, splice_donor_variant, splice_acceptor_variant, stop_gained, stop_lost, and start_lost. The variants reported in ClinVar were further filtered by the quality of supporting evidence in their review status (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/docs/review_status/). In this study, only variants with at least one gold star or more – variants submitted with assertion criteria and evidence – were considered. Finally, for pathogenicity prediction by AlphaMissense, the threshold to classify variants as likely pathogenic was adjusted using the computational framework for missense variant pathogenicity classification proposed by ClinGen Working Group30. Here, the thresholds for pathogenicity scores were iteratively searched to achieve posterior probability for pathogenicity (or benignity) according to the desired strength of evidence (supporting, moderate, strong, or very strong), using a subset of ClinVar variants. The threshold value of 0.907 for AM_LP variants was selected to achieve very strong evidence for pathogenicity (corresponding to the posterior probability of pathogenicity of 0.98).

Responses