Disrupting Amh and androgen signaling reveals their distinct roles in zebrafish gonadal differentiation and gametogenesis

Introduction

Sex determination and gonadal differentiation are fundamental processes in sexual reproduction. Gonadal differentiation involves transformation of undifferentiated gonads into either testes or ovaries, typically triggered by upstream sex determining signals1,2,3,4. While the specific sex-determining genes may vary among vertebrate species, the genes and factors that govern gonadal differentiation appear to be relatively conserved in vertebrates5. This process involves multiple factors, including growth factors such as anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH/Amh) and sex steroids like androgens and estrogens4.

AMH/Amh and androgens, signaling via the androgen receptor (AR/Ar), are both considered critical for male differentiation6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14. In zebrafish, both amh and ar are expressed in somatic cells supporting germ cell development during gonadal differentiation, with ar present in Sertoli cells of the testis and follicle cells in the ovary, and amh in Sertoli cells of the testis and granulosa cells in the ovary15,16,17. However, demonstrating their specific roles in sex differentiation has been challenging. Zebrafish gonadal differentiation exhibits remarkable plasticity and is susceptible to influence by various factors18, making it an excellent model for investigating the intricate actions and interactions of diverse factors. However, disruption of amh and ar genes in zebrafish by different research groups has generated confusing and sometimes conflicting results10,19,20,21,22. This is partly due to the potential influence of endogenous estrogen signaling. To demonstrate the masculinizing effects of various potential male-promoting genes, we have recently adopted a novel strategy of eliminating estrogen production in zebrafish to uncover the roles of male-promoting genes. In zebrafish, the production of estrogens is primarily catalyzed by ovarian aromatase (cyp19a1a). Knocking out the cyp19a1a gene led to the development of an all-male phenotype, driven by various male-promoting factors23,24. Interestingly, simultaneous mutation of both cyp19a1a and dmrt1, a major male-promoting gene, rescued the all-male phenotype in the cyp19a1a mutant, highlighting the potent masculinizing effect of dmrt1 in driving male differentiation25,26. This approach allows us to dissect the roles of other male-promoting factors in gonadal differentiation, such as Amh and Ar.

The same approach has also been used to investigate the roles of female-promoting factors in controlling follicle development. The loss of these factors in zebrafish often leads to an all-male phenotype due to the dominance of the male-promoting pathway, making it difficult to understand their roles in regulating folliculogenesis. By attenuating the influence of the male-promoting pathway, we demonstrated recently that ovarian follicles could develop normally to the pre-vitellogenic (PV) stage without estrogens in the double mutant of cyp19a1a and dmrt1 (cyp19a1a−/−;dmrt1−/−)25,26, in contrast to the conventional view that estrogens are essential for folliculogenesis. Using the same approach, we have recently investigated the roles of oocyte-specific transcription factors Nobox and Figla in follicle development. Disruption of nobox and figla both led to an all-male phenotype; however, simultaneous mutation of dmrt1 weakened the male-promoting pathway in the double mutants (nobox−/−;dmrt1−/− and figla−/−;dmrt1−/−), allowing Nobox and Figla to fully display their roles in folliculogenesis27.

In this study, we employed a similar genetic approach to elucidate the masculinizing effects of Amh and androgens in zebrafish gonadal differentiation and subsequent gametogenesis in male and female gonads. Similar to our previous study on dmrt1 and cyp19a1a25, we generated a double mutant of amh with cyp19a1a (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−) with the aim to evaluate the effect of Amh in gonadal differentiation in the absence of estrogens. As with our previous discovery on dmrt1, the loss of amh also rescued the all-male phenotype of the cyp19a1a single mutant, albeit to a lesser extent, demonstrating its masculinizing effect. In contrast, simultaneous mutation of ar had no such effect in the double mutant with cyp19a1a (ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−). As Amh in zebrafish likely signals through BMP type II receptors (bmpr2a and bmpr2b), especially Bmpr2a as we recently proposed28, we also generated two double mutants of cyp19a1a with either bmpr2a or bmpr2b (bmpr2a−/−;cyp19a1a−/− and bmpr2b−/−;cyp19a1a−/−). The results provided further support for Bmpr2a, but not Bmpr2b, as the dominant receptor mediating Amh actions. Furthermore, we also provided evidence that although Ar was not involved in driving testis differentiation, it played a role in controlling early follicle development and spermatogenesis in differentiated ovaries and testes, respectively.

Results

Roles of Amh and androgen signaling in primary sex differentiation

Primary sex differentiation is influenced by a diverse array of factors. Our previous studies showed that the loss of the aromatase gene cyp19a1a in zebrafish resulted in an all-male phenotype24. This phenotype could be rescued by simultaneous mutation of dmrt1, a male-promoting gene25, highlighting its critical role in zebrafish primary male differentiation. In the present study, we adopted a similar approach to assess the masculinizing impact of Amh and androgens in primary male differentiation, by generating and analyzing double mutant lines: amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/− and ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−. The amh and cyp19a1a mutants were created in our previous studies10,24, while the ar mutant with 7-bp deletion was generated in the present study using the CRISPR/Cas9 method (Supplementary Fig. 1). The double mutant lines lack endogenous estrogen production, providing an ideal system to investigate the potential masculinizing effects of Amh and androgens without confounding influence of estrogenic signaling.

Phenotype analysis at 50 days post fertilization (dpf) revealed that, similar to dmrt1 disruption, loss of amh in the double mutant amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/− could also rescue the all-male phenotype observed in the cyp19a1a−/− single mutant. Histological examination of the double mutant revealed phenotypic heterogeneity. Approximately 30% of the double mutants developed as males (6/20), displaying hypertrophic testes with limited meiosis, mirroring the phenotype of the amh single mutant (amh−/−;cyp19a1a+/−)10. The remaining double mutants developed as either intersexual fish with ovotestes (4/20, 20%) or females with well-formed ovaries containing abundant primary growth (PG) follicles (10/20, 50%), in contrast to the all-male phenotype observed in the cyp19a1a−/− single mutants (Fig. 1). However, these ovaries turned out to be transient, and the females gradually turned into males via sex reversal (secondary sex differentiation). At 90 dpf, no females were found in the double mutants, and most individuals (12/18, 67%) were intersexual, displaying ovotestes with increasingly dominant testicular tissues. Interestingly, the oocytes in the intersexual fish could develop beyond the PG stage to enter the PV stage, indicating successful PG-PV transition or follicle activation (Fig. 2a). At 120 dpf, the majority of the double mutants developed into males (14/16, 87.5%) with only two individuals (2/16, 12.5%) exhibiting an intersexual phenotype (Fig. 2b, c). The gonads of these intersexual fish were largely testes with rudimentary regressing ovarian tissues, which contained only small PG follicles embedded in abundant somatic tissues (Fig. 2b).

Gonadal histology of four different genotypes at 50 dpf: testes and ovaries in controls (amh+/−;cyp19a1a+/−: n = 23 independent fish); hypertrophic testes and ovaries in amh single mutants (amh−/−;cyp19a1a+/−: n = 21 independent fish); all testes in cyp19a1a single mutants (amh+/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 15 independent fish); hypertrophic testes, ovotestes and ovaries in amh and cyp19a1a DMs (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 20 independent fish). PG primary growth follicle, PV pre-vitellogenic follicle, sg spermatogonia, sc spermatocytes, sz spermatozoa, O ovary, T testis.

a Gonadal histology of four different genotypes at 90 dpf: testes and ovaries in controls (amh+/−;cyp19a1a+/−: n = 17 independent fish); hypertrophic testes and ovaries in amh single mutants (amh−/−;cyp19a1a+/−: n = 16 independent fish); all testes in cyp19a1a single mutants (amh+/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 14 independent fish); hypertrophic testes and ovotestes in amh and cyp19a1a DMs (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 18 independent fish). b Gonadal histology of ovotestes in amh and cyp19a1a DMs at 120 dpf (n = 16 independent fish). PG primary growth follicle, PV pre-vitellogenic follicle, FG full-grown follicle, sg spermatogonia, sc spermatocytes, sz spermatozoa. c Sex ratio in four different genotypes of cyp19a1a and amh mutants at 50, 90, 120 dpf.

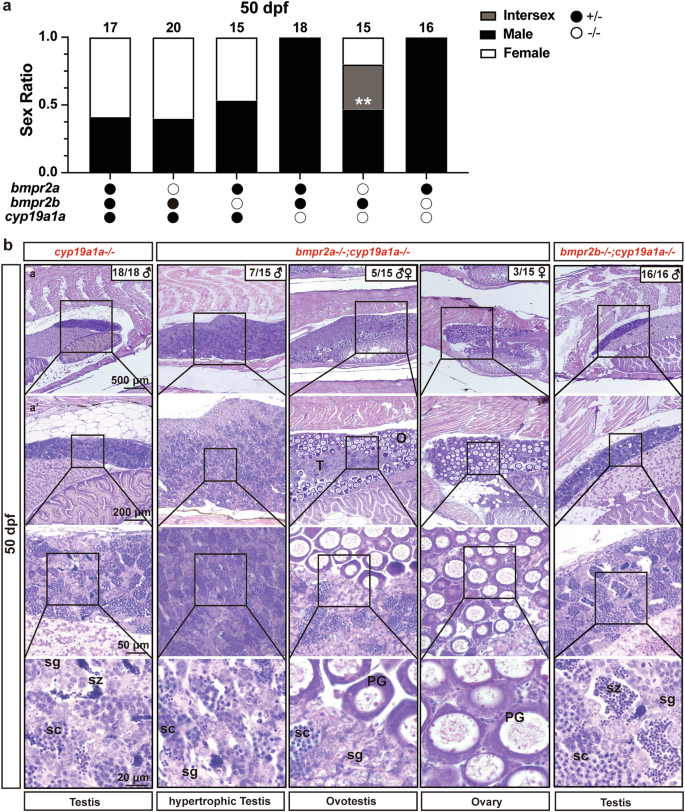

Unlike other vertebrates, zebrafish does not have the specific Amh type II receptor, AMHRII/Amhr2, in its genome. In our previous study, we proposed that zebrafish Amh might signal through a type II receptor of bone morphogenetic proteins (Bmpr2), particularly Bmpr2a28. Given that disruption of Amh could rescue the all-male phenotype observed in the cyp19a1a−/− mutants, we sought to investigate whether its potential receptors (Bmpr2a and Bmpr2b) also share similar functionality. To address this question, we generated two double mutants, bmpr2a−/−;cyp19a1a−/− and bmpr2b−/−;cyp19a1a−/−. Analysis of sex ratios at 50 dpf revealed that the single cyp19a1a−/− mutant showed an all-male phenotype as reported24. Simultaneous mutation of bmpr2a in the double mutant bmpr2a−/−;cyp19a1a−/− reversed the all-male phenotype induced by cyp19a1a mutation, and we could observe three types of individuals in the double mutant: males with hypertrophic testes (7/15, 47%), females (3/15, 20%), and intersexual individuals with ovotestes (5/15, 33%). In contrast, mutation of bmpr2b had no effect on the all-male phenotype in the double mutant with cyp19a1a (bmpr2b−/−;cyp19a1a−/−) (16/16 males, 100%) (Fig. 3). These findings provide compelling evidence supporting the notion that Bmpr2a is likely the type II receptor for zebrafish Amh signaling28, which is involved in promoting but not determining primary gonadal differentiation.

a Sex ratio in six different genotypes of cyp19a1a, bmpr2a, and bmpr2b mutants at 50 dpf. The data were analyzed by Chi-squared test compared with the cyp19a1a single mutants (bmpr2a+/−;bmpr2b+/−;cyp19a1a−/−) (**p < 0.01; p < 0.05 indicate a significant difference). b Gonadal histology of different genotypes at 50 dpf: all testes in cyp19a1a single mutants (bmpr2a+/−;bmpr2b+/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 18 independent fish); hypertrophic testes, ovotestes and ovaries in bmpr2a and cyp19a1a DMs (bmpr2a−/−;bmpr2b+/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 15 independent fish); all testes in bmpr2b and cyp19a1a DMs (bmpr2a+/−;bmpr2b−/−;cyp19a1a−/−: n = 16 independent fish). PG primary growth follicle, sg spermatogonia, sc spermatocytes, sz spermatozoa, O ovary, T testis.

To address the issue of androgen signaling in gonadal differentiation, we generated an androgen receptor mutant (ar−/−) using CRISPR/Cas9 method (Supplementary Fig. 1). Surprisingly, the mutant fish exhibited a normal sex ratio compared to the control fish, suggesting no role for Ar in primary sex differentiation (Fig. 4a). However, the ar−/− males were infertile as they could not induce female spawning (Fig. 4b) and lacked the breeding tubercles in the pectoral fins, a male secondary sexual characteristic (Fig. 4c). Histological examination showed no obvious abnormalities in spermatogenesis of the mutant males compared to the control fish at 50 and 120 dpf except that the mutant testes contained much less mature spermatozoa (Fig. 4d), which were quantified using the method described in our previous study29. In contrast to amh and dmrt1 mutants, which could reverse the all-male phenotype of the cyp19a1a−/− mutant, simultaneous mutation of ar and cyp19a1a in the double mutant (ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−) had no effect on the all-male phenotype of the cyp19a1a−/− mutant (Fig. 4a–e). It is worth noting that although dmrt1, amh, and ar are all considered masculinizing factors, their potency in driving testis development differed significantly as examined at 90 dpf. Dmrt1 was the most potent of the three, as its mutation completely recovered females in the cyp19a1a−/− mutant, with follicles developing fully to the PV stage. In contrast, Amh was less potent; its absence only partially rescued the all-male phenotype in the cyp19a1a−/− mutant, with most individuals being intersexual. Surprisingly, Ar mutation had no effect in preventing male development (Fig. 4e).

a Sex ratio in four different genotypes of ar and cyp19a1a mutants at 50 dpf. b Male fertility was assessed by mating performance, which is defined according to their ability to stimulate spawning of the wild-type (+/+) females. At least five individual male fish of each genotype (+/− or −/−) were tested with the wild-type (+/+) female fish separately. The tests were repeated at 5-day intervals. The spawning rate was defined as the ratio of successful spawning pairs over the total pair number. The experiment was repeated three times (n = 3 independent trial). Data shown are mean ± SEM, p values and statistical significance (p < 0.05) was revealed by unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test. c Genital papilla, a typical female secondary sexual characteristic, was not shown in the male ar+/− and ar−/− fish. The breeding tubercles and typical male secondary sexual characteristics were presented in ar+/− male fish and loss in ar−/− male fish at 120 dpf. Arrowhead: breeding tubercles. d Gonadal histology of ar+/− and ar−/− at 50 (ar+/−: n = 8 fish; ar−/−: n = 10 fish), 120 dpf (ar+/−: n = 5 fish; ar−/−: n = 5 fish); The ratio of mature sperm (spermatozoa) area was calculated using ImageJ by dividing the area of the mature sperm region by the total area of the testis section. Data shown are mean ± SEM, p values and statistical significance (p < 0.05) were revealed by two-tailed unpaired t-test (n = 5 fish). e The phenotypes of disrupting different male-promoting genes, including dmrt1, amh, and ar in cyp19a1a mutants at 90 dpf. PG primary growth follicle, PV pre-vitellogenic follicle, FG full-grown follicle, sg spermatogonia, sc spermatocytes, sz spermatozoa, O ovary, T testis.

Roles of Amh and androgen signaling in folliculogenesis

Although the expression levels of amh and ar in the ovary were lower compared to the testis, they still play roles in ovarian development and function30,31. Previous studies have proposed that Amh may act as a promoting factor in zebrafish follicle activation during the PG-PV transition, as evidenced by the gradual arrest of follicles at the PG stage in aging amh−/− female mutants. However, the first wave of PG-PV transition at puberty onset did not seem to be affected by the loss of Amh10. Regarding steroids, it is worth noting that estrogen signaling is not essential for follicle activation. Disrupting ovarian aromatase (cyp19a1a) did not affect follicle activation or PG-PV transition in both zebrafish (in the absence of dmrt1)25 and medaka32. In comparison, androgen signaling, through a non-aromatizable pathway independent of estrogen signaling, has been implicated in the PG-PV transition in fish species33. However, there has been a lack of genetic data supporting this role for androgens. Our cyp19a1a mutant line provides a valuable tool to assess the roles of Amh and Ar-mediated androgen signaling in early follicle development before sexual maturity, without interference from endogenous estrogens.

Phenotype analysis at 90 dpf revealed the full scale of folliculogenesis from PG to FG stage in the ovary of single amh and ar mutants (amh−/−;ar+/−;cyp19a1a+/− and amh+/−;ar−/−;cyp19a1a+/−) as well as their double mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−;cyp19a1a+/−), comparable to that of the control (amh+/−;ar+/−;cyp19a1a+/−) (Fig. 5a, b). The amh single mutant displayed a greater abundance of PG follicles in the ovary (Supplementary Fig. 2), consistent with our previous report10. Interestingly, in the amh/ar/cyp19a1a triple mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−), all six individuals examined showed either ovaries (2/6) or ovotestes (4/6) in the background of cyp19a1a mutation. This observation revealed the potential collective effects of amh and ar in testis development. It should be noted that follicles in these fish could develop maximally to the early PV stage (PV-I, with a single layer of small cortical alveoli) (Fig. 5a). However, reintroducing ar into the mutant amh−/−;ar+/−;cyp19a1a−/− facilitated follicle development to the late PV stage (PV-III, with multiple layers of large cortical alveoli). These follicles could not progress further to the vitellogenic growth stage due to the absence of estrogens required for vitellogenin biosynthesis in the liver (Fig. 5a, b).

a Ovaries of different genotypes of amh, ar, and cyp19a1a at 90 dpf (n = 3 independent fish/each group). b Follicle diameters of different genotypes in different genotypes of amh, ar, and cyp19a1a at 90 dpf (n = 3 independent fish/each group). The data points shown are diameters of individual follicles, and the statistical significance of the means was demonstrated by unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test. Filled circles:+/−; open circles:−/−. PG (primary growth, <150 µm), PV (pre-vitellogenic, ~250 µm), EV (early vitellogenic, ~350 µm), MV (mid-vitellogenic, ~450 µm), LV (late vitellogenic, ~550 µm) and FG (full-grown, >650 µm). Me meiotic cells.

Roles of Amh and androgen signaling in testis growth and spermatogenesis

Amh and androgens are believed to play roles in male development, including primary and secondary characteristics. In zebrafish, the loss of Amh has been reported to induce testis hypertrophy with reduced meiotic activity10,19,20; while mutation of the androgen receptor ar resulted in a suppression of testis growth and spermatogenesis, a lack of male secondary sex characteristics, and male infertility due to their inability to engage in natural spawning with normal females21,22,34. Although these studies implicated Amh and Ar in male development, their interaction in the process remains largely unknown. In the present study, we found that the loss of amh resulted in a significant increase in ar expression in the testis. Similarly, in the testes of ar−/− mutants, the expression of amh also increased significantly22,28. These results suggest potential compensatory roles for Amh and Ar in testis development and spermatogenesis. To address this issue, we generated a double mutant of amh and ar (amh−/−;ar−/−) and compared its phenotypes in males to those of single mutants (amh−/− and ar−/−).

Histological examination at 90 dpf revealed severely impaired spermatogenesis with little spermatogenic activity in the double mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−), with testes arrested at the pre-luminal stage (PL, stage I) according to the staging criteria we recently proposed35. These testes contained primarily spermatogonia with a limited number of early spermatocytes, lacking any tubular lumina and mature spermatozoa. In contrast, both single mutants, amh−/− and ar−/−, exhibited normal spermatogenesis with all stages of spermatogenic cells; however, their testes were at mid-luminal stage (ML, stage III), characterized by open lumina with small amount of mature spermatozoa, compared to the late luminal stage (LL, stage IV; open lumina with mass amount of spermatozoa) in the control. The more severe phenotype of the double mutant indicates additive effects of amh−/− and ar−/− mutations and compensatory roles for both Amh and Ar in spermatogenesis (Fig. 6a).

a Testes of different genotypes at 90 dpf (n = 3 independent fish/each group). b The dissected testes (fixed by Bouin’s solution) of different genotypes at 90 dpf (n = 3 independent fish/each group). c GSI of different genotypes at 90 dpf. The GSI was determined on fixed samples (fixed gonad weight/ the body weight of the fixed fish). Data shown were mean ± SEM, p values and statistical significance (p < 0.05) was revealed by unpaired Student’s two-tailed t-test. (amh+/−;ar+/−: n = 4 independent fish; amh−/−;ar+/−: n = 6 independent fish; amh+/−;ar−/−: n = 4 independent fish; amh−/−;ar−/− : n = 6 independent fish). d Expression of ar in the testes of male amh mutants and controls. Data shown are mean ± SEM, p values and statistical significance (p < 0.05) was revealed by two-tailed unpaired t-test (n = 4 independent fish). e Expression of fshb and lhb in the pituitary of male amh and ar single and double mutants (amh−/−;ar−/− : n = 4 independent fish; other groups: n = 3 independent fish). Data shown are mean ± SEM, p values and statistical significance (p < 0.05) was revealed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test. sg spermatogonia, sc spermatocytes, sz spermatozoa.

One distinct phenotypic difference between amh and ar mutants was their effect on testis growth. As we previously reported10,28, loss of amh resulted in significant testis hypertrophy at 90 dpf (Fig. 6a, b) with an increased gonadosomatic index (GSI) (Fig. 6c). In contrast, ar mutation did not induce testis hypertrophy; instead, the mutant testes were significantly smaller than controls (Fig. 6c). Interestingly, double mutation of amh and ar (amh−/−;ar−/−) significantly reduced the testis hypertrophy observed in the amh single mutant (Fig. 6a–c). Gene expression analysis revealed a robust increase in ar expression in amh−/− testes (Fig. 6d). Conversely, the expression of pituitary follicle-stimulating hormone (fshb) but not luteinizing hormone (lhb) decreased significantly in the amh mutant but increased significantly in the ar mutant. This increase in fshb expression persisted in the pituitary of the double mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−) compared to amh single mutant (amh−/−) (Fig. 6e). It is worth noting that, while ar mutation effectively prevented hypertrophic testis growth in the amh mutant at 90 dpf, this effect gradually receded with age. By 180 dpf, the testes of the double mutant also exhibited significant hypertrophy, approaching the control level (Fig. 7).

a Testes of different genotypes at 180 dpf; The degree of development can be divided as follows: preluminal (PL, stage I; no tubular lumina in testis), early luminal (EL, stage II; open tubular lumina without mature spermatozoa), mid-luminal (ML, stage III; open lumina with a small number of mature spermatozoa) and late luminal (LL, stage IV; open lumina with abundant mature spermatozoa). b The dissected testes (fixed by Bouin’s solution) of different genotypes at 180 dpf. c GSI of different genotypes at 180 dpf (n = 3 independent fish/each group). Data shown were mean ± SEM, p values and statistical significance (p < 0.05) was revealed by one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s test.

Discussion

Unlike mammals, birds, and some fish species, the majority of invertebrates and lower vertebrates do not have sex chromosomes or sex-determination genes, which makes their sex-determination and differentiation processes intricate4. The sex determination in zebrafish is polygenic, resulting from the interplay of various factors36. The Dmrt1 pathway, Amh signaling, and androgen signaling represent three principal pathways involving transcriptional factors, growth factors, and steroids, respectively, that facilitate male differentiation. Dmrt1 is a well-known male-promoting factor in vertebrates. However, the masculinizing effects of Amh and Ar are less understood and sometimes contested, especially in lower vertebrates like fish. In this study, we evaluated the male-promoting effects of amh and ar in zebrafish, referencing our recent work on dmrt125, using a novel genetic approach involving various mutant lines including single mutants (amh−/− and ar−/−), double mutants (dmrt1−/−;cyp19a1a−/−, amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−, ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−, bmpr2a−/−;cyp19a1a−/−, bmpr2b−/−;cyp19a1a−/− and amh−/−;ar−/−), and triple mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−). The key point of this approach is to create an estrogen-deficient zebrafish model, allowing for unhindered observation of the masculinizing effects of different male-promoting factors without interference by endogenous estrogens.

As an early marker of testicular differentiation, AMH is expressed in the embryonic testis but not the ovary in mammals, and its expression in the ovary starts after birth37. In non-mammalian vertebrates such as birds and fish, AMH is expressed in the developing gonads of both sexes but predominantly in the testis38,39. AMH expression in the early fetal testis is regulated by several key transcription factors, including SRY, SOX9, SF-1, WT1, and GATA440, suggesting an important role for AMH in male differentiation. However, targeted mutation of AMH/MIS in mice did not result in any deviation of sex ratio, with all individuals carrying the Y chromosome developing as males6. This agrees well with our recent study in zebrafish without a Y chromosome, which demonstrated that loss of amh did not significantly impact the sex ratio compared to controls10. However, different zebrafish studies in different amh mutants have reported different sex ratios10,19,20. The reason for this discrepancy remains unclear but could be attributed to the inherent high plasticity of zebrafish sex determination and differentiation, which is due to the lack of master sex-determining genes, rendering their sex differentiation process susceptible to internal and external factors.

To further elucidate the role of Amh in gonadal differentiation, we employed a novel approach in the present study: the generation of an estrogen-deficient zebrafish model. By deleting aromatase gene cyp19a1a to attenuate the female-promoting pathway, this strategy aimed to reveal the full masculinizing potential of male-promoting factors, such as Amh, in driving testis development. Similar approaches have been proven effective in our previous studies, demonstrating the crucial role of dmrt1 in male development25 and dissecting the distinct functions of figla and nobox in female development and folliculogenesis27.

As previously reported, the cyp19a1a mutant exhibited complete masculinization, with all individuals developing as males24. However, the additional mutation of amh in the double mutant (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−) rescued the all-male phenotype observed in the cyp19a1a single mutant, resulting in ovarian formation. This phenotypical rescue was recapitulated in the bmpr2a mutant but not the bmpr2b mutant, supporting our previous proposal that Bmpr2a, rather than Bmpr2b, likely serves as the type II receptor for Amh in zebrafish28. These findings provide unequivocal evidence that, in the absence of endogenous estrogens, Amh signaling is critical for driving testis differentiation. However, the masculinizing effect of Amh in gonadal differentiation is obviously weaker than Dmrt1. First, the loss of Dmrt1 could fully rescue the all-male phenotype of cyp19a1a mutant in the double mutant (dmrt1−/−;cyp19a1a−/−), allowing the ovaries to develop fully with follicles reaching the full size of PV stage25. However, in the double mutant of amh and cyp19a1a (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−), although the ovaries initially formed fully in young females, they eventually turned into ovotestes with testicular tissues before the follicles entered the PV stage. Second, spermatogenesis proceeded normally in the testicular parts of the ovotestes in the double mutant (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−), in contrast to the complete cessation of spermatogenesis in the double mutant of dmrt1 and cyp19a1a (dmrt1−/−;cyp19a1a−/−).

In addition to participation in gonadal differentiation, AMH is also known to participate in testis growth and spermatogenesis. In zebrafish, Amh suppresses the proliferation of spermatogonia in the testis while promoting differentiation of their exit to advanced stages, which contributes to the maintenance of testis homeostasis and spermatogenesis19,20,28. Mutation of amh results in testis hypertrophy (due to hyperproliferation of spermatogonia) and suppression of spermatogenesis10,28. We also observed in the present study that the hypertrophic testis growth was accompanied by impaired spermatogenesis in the amh mutant.

AMH is also known to play roles in ovarian development and folliculogenesis. It is produced by granulosa cells in the ovary from birth in mammals40, suggesting its potential roles in the ovary. In birds and fish, AMH is also expressed in the ovary, although its expression level is lower than that in the testis38,39. In agreement with our previous study10, we did not observe obvious abnormalities in the ovary of young amh mutant in terms of folliculogenesis up to 90 dpf except relatively more abundant PG follicles. In the double mutant (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−), the follicles in the ovotestes could develop up to the PV stage but not stages of vitellogenic growth. This was most likely due to the lack of aromatase (cyp19a1a), therefore leading to failure in vitellogenin synthesis in the liver.

Androgen signaling via AR is widely recognized for its crucial role in male development. However, despite their masculinizing effects on the secondary sex characteristics, androgens do not have the testis-inducing capacity in female mammals41,42,43. Also, the testes can still form without AR in various models, including fish, although this is often accompanied by suppression or even defective spermatogenesis13,21,22,44. These findings suggest a more nuanced role for androgen signaling in sex differentiation than previously thought. To further elucidate the specific contributions of androgen signaling via Ar in sex differentiation and gametogenesis, we adopted the same approach in the present study to examine the phenotype of ar mutation in an estrogen-deficient background, which would help unmask the potential masculinizing effects of androgen signaling without interference by estrogens.

In contrast to the all-male phenotype observed in cyp19a1a mutant and mutants of estrogen receptors (esr1, esr2a, and esr2b)24,45, our results showed that the loss of androgen receptor ar did not affect the sex ratio, suggesting that androgen signaling via Ar is not essential for the primary sex differentiation. Supporting this conclusion, knockout of cyp11c1, which disrupted androgen synthesis in zebrafish, showed a sex ratio comparable to the wild-type control14. Similarly, knockout of ara and arb in medaka did not lead to sex reversal in XY mutants, further reinforcing the view that androgens play a dispensable role in gonadal sex determination in at least some teleosts44.

Previous studies on ar mutant zebrafish reported varying observations regarding sex ratios. Tang et al. did not report sex ratios22, while Yu et al. observed a feminized sex ratio of approximately 62:38 (female:male)21. A subsequent study by Crowder et al. described a more pronounced feminization, with ~80% female offspring34. These results suggest potential variability in the impact of ar mutations on sex differentiation. In contrast, our study using a newly generated ar mutant allele did not reveal a significant sex ratio bias, in contrast to the female-biased ratios reported in previous studies21,34. While smaller sample sizes in some studies could lead to spurious deviations from expected sex ratios, the sample sizes used in our study are believed to be sufficient to detect significant deviations. Such discrepancies may also stem from inherent differences between laboratory strains of zebrafish. Zebrafish sex ratios are known to be highly variable and influenced by both genetic and environmental factors18. Strain-specific differences in the genetic mechanisms of sex differentiation likely contribute to the variation observed across studies. Furthermore, environmental conditions, such as temperature, population density, and water quality, may further complicate the interpretation of sex ratios18. These factors highlight the complexity of zebrafish sex differentiation and the challenges in drawing consistent conclusions across studies.

To further investigate the role of Ar in primary sex differentiation, we generated an ar mutant in an estrogen-deficient background. We hypothesized that if Ar promotes testis differentiation, its disruption might rescue the all-male phenotype induced by estrogen deficiency. However, the ar mutation did not rescue this phenotype, unlike the rescue observed with dmrt1 and amh mutants. This result further supports the conclusion that Ar does not play a significant role in primary gonadal differentiation and testis formation.

However, our findings underscore the critical role of ar in male reproductive functions as the mutant males lacked specific secondary sex characteristics and were infertile. Histological analysis showed the presence of mature sperm, albeit significantly less than in controls, indicating that the androgen pathway is not indispensable for sperm maturation. These findings align with previous reports on ar mutation in zebrafish22,34, which demonstrated successful in vitro fertilization using sperm from ar mutants, further confirming that the absence of androgen signaling does not entirely block spermatogenesis34. Interestingly, another study demonstrated that progesterone could promote sperm maturation through the progesterone pathway in the absence of androgen signaling46. Despite its dispensable role in primary sex differentiation, androgen signaling via Ar appears to play an important role in driving spermatogenesis.

Having characterized the phenotypes of amh and ar single mutants in sex differentiation and gametogenesis, we next investigated the interplay between Amh and Ar signaling in gonadal growth and gametogenesis. As previously reported10,28, the loss of amh and its receptor, bmpr2a, caused severe gonadal hypertrophy, particularly in the testes. Despite the excessive growth of the testes, spermatogenic activity was significantly impaired. The mutant testes were primarily composed of spermatogonia, with reduced meiotic activity and progression through the subsequent stages of spermatogenesis.

Intriguingly, simultaneous mutation of amh and ar in the double mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−) significantly reduced testis hypertrophy at 90 dpf, although this effect of ar attenuated at a later stage (180 dpf). This finding strongly suggests that androgen signaling via Ar might act as a downstream mechanism contributing to the hypertrophic growth of the amh−/− testes. This notion is further supported by the robust increase of ar expression in amh−/− testes. We recently proposed that the gonadal hypertrophy observed in amh mutant is gonadotropin-dependent because simultaneous mutation of gonadotropin receptors (fshr and lhcgr) completely abolished the hypertrophic growth of amh−/− gonads28. Our current discovery adds another layer to this mechanism, implicating androgen signaling in the hypertrophic process as well, although its contribution appears less pronounced than that of gonadotropins. It is worth noting that the loss of ar also reversed the decreased expression of pituitary FSH (fshb) observed in the amh mutant, suggesting a negative feedback loop between gonadotropin expression and androgen signaling. Interestingly, although spermatogenesis proceeded normally in the testes of both amh and ar single mutants with a production of mature spermatozoa, albeit at reduced levels, it was completely abolished in the testes of the double mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−). This finding strongly suggests that both Amh and Ar are required for the initiation and/or maintenance of spermatogenesis and they have strong compensatory effects in the process (Fig. 8a).

a The roles of Amh and androgen in testis differentiation. Amh inhibits spermatogonial proliferation and promotes spermatogonial differentiation, while Ar supports spermatogenesis. Amh and Ar have complementary roles in promoting spermatogenesis, as the absence of either Amh or Ar still allows the production of mature sperm; however, the simultaneous absence of both Amh and Ar completely blocks spermatogenesis. b The roles of Amh, androgen, and estrogen in early follicle development. Amh and androgen are involved in follicle activation, or PG-PV transition, which marks puberty onset in females. While estrogen plays no direct role in the PG-PV transition, it is crucial for the subsequent transition from pre-vitellogenic to vitellogenic growth or PV-EV transition. The effects of estrogen on follicle development are more pronounced than those of Amh and androgen. The subtle roles of Amh and androgen are primarily revealed in the absence of estrogen signaling. c Zebrafish sex differentiation is orchestrated by the antagonistic interplay between female- and male-promoting factors, with estrogens playing a key feminizing role. We investigated the roles of Dmrt1, Amh, and androgen signaling (via the androgen receptor, Ar) in counteracting this estrogenic influence. Our findings reveal a hierarchy of masculinizing potency: Dmrt1 exhibits the strongest anti-estrogenic activity, followed by Amh, while Ar plays a negligible role in promoting male differentiation.

In addition to its roles in testis development and spermatogenesis, androgen signaling has also been implicated in regulating ovarian function. Studies in mammals have demonstrated AR expression in the ovary, predominantly in granulosa cells and, to a lesser extent, in theca and stromal cells. This expression pattern appears to be functionally relevant, as AR expression levels positively correlate with granulosa cell proliferation and negatively with apoptotic activity47. Furthermore, AR knockout mice exhibit reduced fecundity compared to wild-type females, suggesting a role for AR in female fertility13. In teleosts, androgen signaling has been implicated in regulating folliculogenesis, particularly during the early stages of follicle development, such as the transition from primary to secondary growth33,48. However, direct genetic evidence supporting the role of androgens in fish folliculogenesis had been lacking. Recent studies in zebrafish showed that lack of ar resulted in progressive deterioration of the ovary after 120 dpf21 and that the mutant females showed signs of premature ovarian failure at later stages21,34.

In the present study, we did not observe any noticeable abnormalities in the ovaries of ar mutant zebrafish up to 90 dpf. However, when examined in conjunction with amh and cyp19a1a mutations, the loss of ar revealed a significant effect on early follicle development, especially the PG-PV transition or the transition from primary to secondary growth. In the amh and cyp19a1a double mutant (amh−/−;cyp19a1a−/−), ovaries formed in over half of the individuals, and the follicles could undergo PG-PV transition to reach the late PV stage (PV-III). However, the additional mutation of ar in the triple mutant (amh−/−;ar−/−;cyp19a1a−/−) arrested follicle development at the PG stage, with only a few follicles entering the early PV stage (PV-I). This key finding provides compelling genetic evidence supporting a role for androgens in early follicle development. It is worth noting that this effect was only apparent in the absence of both amh and cyp19a1a, suggesting that the influence of androgens on early folliculogenesis is subtle and potentially masked when estrogen signaling is present (Fig. 8b).

In conclusion, using a novel genetic approach, the present study investigated the potential masculinizing effects of Amh and Ar in gonadal differentiation and gametogenesis in an estrogen-deficient zebrafish model. Our findings reveal a hierarchy of masculinizing potency among the factors examined, with Dmrt1 exhibiting the strongest anti-estrogenic activity, followed by Amh. In contrast, Ar showed minimal, if any, impact on counteracting estrogen-mediated feminization. These results demonstrate a role for Amh, but not Ar, in promoting male differentiation (Fig. 8c). While dispensable for sex determination and differentiation, Ar is nonetheless essential for spermatogenesis, folliculogenesis, and male secondary sexual characteristics, with its loss resulting in male infertility.

Methods

Animal

All experiments were conducted using AB strain zebrafish (Danio rerio). The alleles cyp19a1aumo5, amhumo17, bmpr2aumo25, and bmpr2bumo26 were produced in our previous studies10,24,28, were utilized in this investigation. The ar−/− mutant allele was created in this study using CRISPR/Cas9. The fish were maintained at 28 ± 1 °C with a photoperiod of 14 h of light and 10 h of dark in an environmental chamber (Thermal Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and a flow-through aquarium system (Tecniplast, Buguggiate, Italy). Water pH was maintained around 7.3, conductivity at 400 mS/cm, and temperature at 28.0 °C. Larvae were fed Paramecium and Artemia, while adults received Artemia and commercial dry food.

Zebrafish were euthanized by immersion in a buffered tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) solution at a concentration of 0.25 mg/mL (pH 7.0–7.5). Fish were immersed in the solution until the cessation of opercular movement to ensure euthanasia. All experiments were conducted in accordance with the standards and regulations of the University of Macau’s Research Ethics Committee (Approval. No. AEC-13-002). We have complied with all relevant ethical regulations for animal use.

Generation of ar null zebrafish mutant line

The CRISPR/Cas9 system was utilized to generate mutations in the ar gene of zebrafish, following established protocols25,49,50. Briefly, an sgRNA was designed via CRISPRscan (https://www.crisprscan.org) to target exon II of ar while minimizing off-target effects (Supplementary Table 1). The sgRNA and Cas9 mRNA were produced by in vitro transcription from DraI-digested pDR274 (Addgene Plasmid #42250) and pCS2-nCas9n (Addgene Plasmid #47929) using the mMACHINE T7 and SP6 kits (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocols. Subsequently, a 4.6 nl injection mixture containing 60 ng/μl sgRNA and 200 ng/μl Cas9 mRNA was injected into one- or two-cell-stage embryos with a Drummond Nanoject system (Drummond Scientific, Broomall, PA). F0 embryos were initially screened for mutations using high-resolution melting analysis (HRMA) and a heteroduplex mobility assay (HMA)51,52,53, with positive results confirmed by sequencing. Mosaic F0 founders were then outcrossed with wild-type fish to produce heterozygous F1 progeny (ar+/−), and subsequent intercrossing of F1 siblings with the same mutation generated homozygous F2 mutants (ar−/−). A seven-base pair deletion ar (−7/−7) line was chosen for further analysis and experiments (Supplementary Fig. 1), as it is predicted to cause a frameshift that abolishes the synthesis of a functional Ar protein.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA from each embryo or a small piece of the caudal fin was extracted by alkaline lysis according to our previous studies51. Samples were incubated in 30–50 µl of 50 nmol/µl NaOH at 95 °C for 10 min to extract the DNA. Following extraction, 3–5 µl of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) was added for neutralization. The DNA extract was then used for HRMA, and the melt curves were analyzed using the Precision Melt Analysis software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) according to our previous studies51. Primers used for genotyping are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Sampling and histological examination

The fish were sampled at various time points for phenotype analysis. They were euthanized following anesthesia with MS-222 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Each fish’s gross morphology was photographed with a Canon EOS 700D digital camera (Canon, Tokyo, Japan). The pectoral fins and cloaca were examined under the Nikon SMZ18 dissecting microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and photographed with the Digit Sight DS-Fi2 camera (Nikon).

For histological analysis, the entire fish were fixed in Bouin’s fixative for a minimum of 24 h. Dehydration and infiltration were carried out using the ASP6025S automatic vacuum tissue processor (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). The samples were then embedded in paraffin and serially sectioned at 5 µm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and observed under the Nikon ECLIPSE Ni-U microscope (Nikon), with images captured using the Digit Sight DS-Fi2 camera (Nikon). Sibling wildtype (+/+) and/or heterozygous (+/−) fish served as controls for the phenotype analysis.

Follicle staging and quantification

Follicles were staged based on their size and morphological characteristics, including the presence of cortical alveoli and yolk granules, as previously described54,55,56. We divide follicles into six stages: PG (primary growth, <150 µm), PV (pre-vitellogenic, ~250 µm), EV (early vitellogenic, ~350 µm), MV (mid-vitellogenic, ~450 µm), LV (late vitellogenic, ~550 µm), and FG (full-grown, >650 µm). To analyze the follicle ratio in the ovary, we conducted serial longitudinal sectioning of the entire fish at a thickness of 5 μm. For each individual, the largest ovarian section was selected for follicle quantification using NIS-Elements BR software (Nikon), according to our previous studies57,58. The ratio of PG follicles was calculated by dividing the number of PG follicles in each section by the total number of follicles.

Sex identification

In general, sex was determined based on sexually dimorphic morphological characteristics, such as body shape, fin coloration, and the appearance of the genital papilla59. If necessary, dissection was performed using the Nikon SMZ18 stereomicroscope (Nikon). At the conclusion of sampling, histological analysis was conducted to confirm the sex identity.

RNA extraction and quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the testis or pituitary using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Reverse transcription was performed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was conducted using 2× SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Bio-Rad) on the CFX384 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) utilizing the primers provided in Supplementary Table 1 with the following thermal cycling conditions: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 20 s, 72 °C for 30 s, and 84 °C for 8 s. Primer specificity was verified via melting curve analysis. Gene expression levels were normalized to ef1a and expressed as a fold change relative to the control group. The data were analyzed using the 2^−ΔΔCt method.

Statistics and reproducibility

The sample sizes shown in figure legends were determined based on statistical requirements, the need for experimental reliability, and sample availability. Each group had at least three phenotypic replicates. To analyze sex ratios, the sample sizes were much larger as required by the assessment. All values are presented as the mean ± SEM, p values, and statistical significance (p < 0.05) were analyzed by Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA using Prism 9 (GraphPad Prism, San Diego, CA). The significance levels are indicated in the figures by exact p values or asterisk (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; p > 0.05 or ns not significant). Sample sizes correspond to independent biological replicates, and all experiments were conducted at least twice. All individual data values plotted in the figures were contained in Supplementary Data (Supplementary Data 1).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses