Distinct age-related characteristics in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: patient reported outcomes and measures of gut physiology

Introduction

With a prevalence of ~4–10%, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), characterized by chronic or recurrent abdominal pain and altered bowel habits, i.e., diarrhea and/or constipation is one of the most common disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI)1,2,3. While IBS is common among all ages, studies have reported higher prevalence rates in younger individuals, with a decline in prevalence observed in older age1,2,4,5. Younger IBS patients have more severe gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and health-related quality of life is more deteriorated6. Although older individuals tend to report fewer GI symptoms in general7, there are specific symptoms that are reported more often among older individuals, including fecal incontinence8,9,10 and constipation11,12. Contributing factors to more severe GI symptoms in younger populations is not fully understood, but both psychological and physiological factors may contribute. Recent epidemiological studies found that psychological distress is more common among younger individuals, in line with the higher prevalence of IBS2,13. Further, a recent study has shown that visceral hypersensitivity, i.e., increased intensity of visceral sensations or decreased pain threshold for visceral stimuli, is less common in older individuals14. The effects of aging on colonic motility are unclear, with some studies reporting slower transit with older age, and other studies that show no change in transit time with older age15,16,17. Aging has a distinct effect on the anorectal function, with reduced basal and maximum anal sphincter tone, and decreased rectal compliance and increased sensory thresholds16,18,19. However, whether age-related changes in GI sensorimotor function are associated with specific GI symptoms remains unclear. Intestinal barrier dysfunction, present in inflammatory bowel disease and celiac disease, can result in intestinal damage and inflammation, and scientific research has also shown alterations in patients with IBS20,21. Whether intestinal barrier (dys)function is associated with age in patients with IBS has yet not been investigated.

Understanding the associations between IBS and age is crucial for tailoring diagnostic approaches, treatment strategies, and patient education. A limitation of the existing literature is that predominantly younger IBS patients are included in studies, and there are currently no data available that assessed age-related differences in factors of gut physiology in a large IBS population. No studies have assessed the combination of patient reported outcomes and multiple factors of gut physiology in younger versus older age groups. We hypothesize that age is associated with the severity of specific GI symptoms, and that factors of gut physiology can partially explain the differences in GI symptoms in IBS patients of different age. This study aimed to characterize IBS patients of different ages, by comparing patient reported outcomes and measures of gut physiology, and to explore potential associations between age, measures of gut physiology, and GI symptoms.

Results

Participants

In total, 1677 patients with IBS were included with a mean age of 39.2 ± 13.8 years and a mean body mass index (BMI) of 24.3 ± 4.2 kg/m2. The study population was predominantly female (74%) and with demographic and baseline characteristics given in Table 1. Based on the Rome III questionnaire 32% had IBS with predominant diarrhea (IBS-D), 33% IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C), 15% IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M), and 20% unspecified IBS (IBS-U). The severity of GI symptoms (Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale (GSRS)-IBS) was similar across the different Rome criteria and generally worse in females.

Age is associated with patient reported outcomes and factors of gut physiology

Linear regression analyses revealed that most of the patient reported outcomes and measures of gut physiology were associated with age, with decreasing severity observed for older age regarding GI symptoms, non-GI somatic symptoms, anxiety, and GI-specific anxiety (Table 2). Notably, severity of constipation and depression was not associated with age. Quality of life increased with increasing age including the domains related to emotional, mental, food, social role, and physical role, but sleep-related quality of life decreased with increasing age.

Oro-anal transit (radiopaque markers) was slower with increasing age, and in line with this the colonic transit and whole gut transit (wireless motility capsule) were also slower with increasing age. There were no associations between age and gastric emptying time or small intestinal transit time, see Table 2 for more details.

Sex-specific analyses are presented in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. In general, we found similar results, but also some sex-specific differences. Younger age was associated with severity of abdominal bloating and non-GI somatic symptoms, and the food and emotional domains of quality of life in females, but not in males. Furthermore, aging was associated with slower transit in females, but not in males.

Characteristics of IBS patients of different age

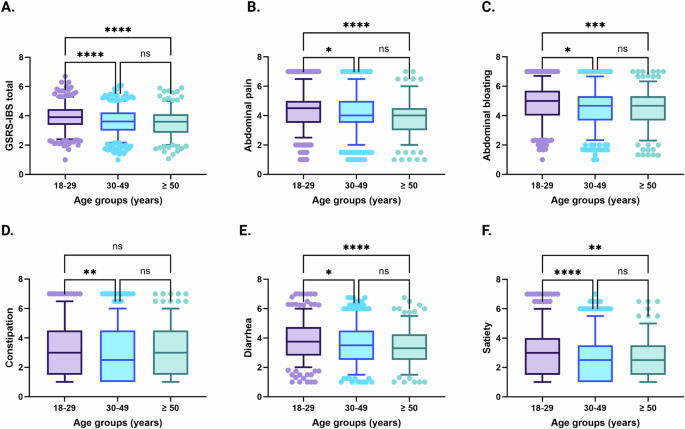

The IBS patients were stratified into age groups (18–29 years; n = 761; 45%, 30–49 years; n = 484; 29%, ≥50 years; n = 432; 26%) and distribution of sex was similar across age groups (18–29 years; females n = 595; 77%, 30–49 years; females n = 353; 73%, ≥50 years; females n = 299; 69%). The severity of all individual GI symptoms, as well as overall GI symptom severity, were different across age groups (Fig. 1). More specifically, abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, diarrhea, satiety, and overall GI symptom severity was worse in the youngest compared with the intermediate and oldest age groups. Severity of constipation was worse for the youngest vs. the intermediate age group, but not different between younger versus the oldest IBS patients. The severity of non-GI somatic symptoms was lower in the oldest compared with the two younger age groups. Among psychological symptoms, general anxiety and GI-specific anxiety was gradually decreasing by age groups, while depression was unaltered. In the oldest age group, quality of life was better than or similar to the younger ages groups except for sleep (Table 3).

Severity of GI symptoms, including overall GI symptom severity (A), abdominal pain (B), abdominal bloating (C), constipation (D), diarrhea (E), and satiety (F), across different age groups in IBS. 18–29 years; n = 546, 30–49 years; n = 329, ≥50 years; n = 251. Data are presented as mean with 5th and 95th percentiles. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

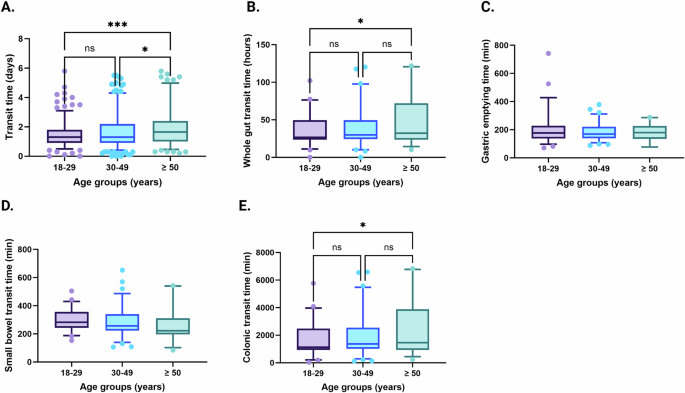

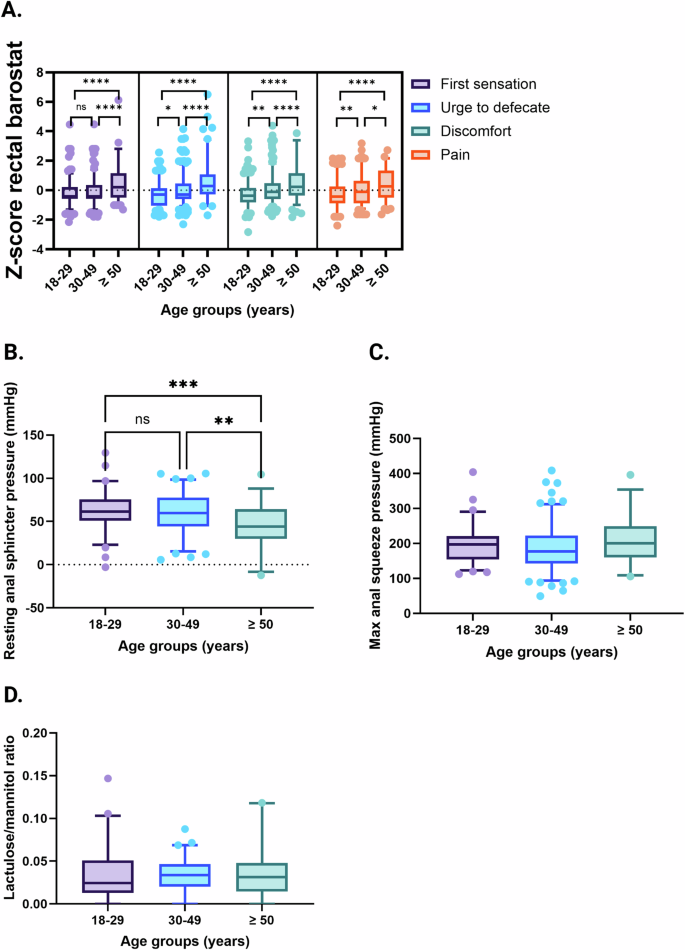

While gastric emptying time and small bowel transit time was similar in all, measures of gut transit involving the colon (oro-anal transit and colonic transit) became slower by age group (Fig. 2). Rectal sensory thresholds were lower in the youngest age group compared with both the intermediate and oldest age groups, and the intermediate age group also had lower rectal sensory thresholds compared with older IBS patients. The oldest age group had lower resting anal sphincter pressures compared with younger age groups, but no differences were observed for maximum anal squeeze pressure. The lactulose/mannitol ratio that reflects small bowel permeability was similar in the different age groups (Fig. 3).

Transit times, including total transit time measured by radiopaque markers (A), whole gut transit time (B), gastric emptying time (C), small bowel transit time (D) and colonic transit time (E) measured by wireless motility capsule, across different age groups in IBS. Radiopaque markers: 18–29 years; n = 352, 30–49 years; n = 210, ≥50 years; n = 129. Wireless motility capsule: 18–29 years; n = 52, 30–49 years; n = 79, ≥50 years; n = 26. Data are presented as mean with 5th and 95th percentiles. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Rectal sensitivity, including first sensation, urge to defecate, discomfort, and pain thresholds assessed by rectal barostat procedures combined into Z-scores (A), resting anal sphincter pressure (B) and maximum anal squeeze pressure (C) measured by anorectal manometry, and lactulose/mannitol ratio measured during small bowel permeability testing (D), across different age groups in IBS. Rectal sensitivity: 18–29 years; n = 315, 30–49 years; n = 193, ≥50 years; n = 115. Anorectal manometry: 18–29 years; n = 68, 30–49 years; n = 86, ≥50 years; n = 33. Small bowel permeability: 18–29 years; n = 49, 30–49 years; n = 61, ≥50 years; n = 26. Data are presented as mean with 5th and 95th percentiles. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Associations between age, measures of gut physiology, and severity of GI symptoms

Age, sex, psychological distress (HADS), transit time (radiopaque markers), and rectal sensitivity (rectal discomfort thresholds) were included in the combined linear regression analyses where female sex and more severe psychological distress were independently associated with more severe overall GI symptoms and abdominal bloating (Table 4). The combined model of age, sex, psychological distress, and measures of gut physiology explained 13.8% of the variation in severity of overall GI symptoms and 14.1% of the variation in severity of abdominal bloating.

More severe psychological distress and lower rectal discomfort thresholds were independently associated with more severe abdominal pain. The combined model of age, sex, psychological distress, and measures of gut physiology explained 11.8% of the variation in severity of abdominal pain.

A more rapid transit and more severe psychological distress were independently associated with more severe diarrhea and a slower transit was independently associated with more severe constipation. The combined model of age, sex, psychological distress, and measures of gut physiology explained 15.2% of the variation in severity of diarrhea, and 16.0% of the variation in severity of constipation.

Younger age, a slower transit and more severe psychological distress were independently associated with more severe satiety. The combined model of age, sex, psychological distress, and measures of gut physiology explained 8.3% of the variation in severity of satiety.

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate the importance of age regarding the severity of GI and non-GI symptoms, quality of life, and gut physiology in a large IBS population. We show distinct age-related characteristics, with younger IBS patients having more severe GI, non-GI, and psychological symptoms, and worse quality of life. Furthermore, we observe age-related differences in GI sensorimotor function, as older IBS patients are less sensitive to rectal balloon distensions, have lower resting anal sphincter pressures, and have slower gut transit times in measures involving colon. Exploratory analyses that combined sex, age, psychological distress and measures of gut physiology suggested that age-related changes in GI sensorimotor function may partially explain the severity of specific GI symptoms.

Previous epidemiological studies have highlighted that the prevalence and the severity of IBS decreases with age2,4,5,22, and our data confirm the latter as more severe GI symptoms were associated with younger age. Previous studies have reported symptoms of constipation to be more prevalent and more severe in older individuals2,4,5,7,8,11,13,22. We did not find a clear association between increasing age and constipation in the context of IBS, as the youngest age group of patients with IBS had the most severe symptoms of constipation compared with the intermediate group, but with no differences were observed between the youngest and oldest age groups. An explanation for this may be that other factors, such as physiological and psychological factors, could be of importance regarding the severity of constipation symptoms in younger and older IBS patients. We show that older IBS patients have slower transit, which is associated with more severe symptoms of constipation23, and younger IBS patients have more severe psychological distress and are more sensitive to rectal balloon distensions, which are both associated with more severe symptoms24,25. Moreover, for the other GI symptoms, our data show that younger age is associated with more severe symptoms overall. Group comparisons show that especially the youngest group of patients with IBS have more severe GI symptoms, while those of intermediate and older age had similar GI symptom intensities. As suggested by previous studies, these differences may be due to other factors related to symptom reporting, including more severe psychological distress and other (non-GI) somatic symptoms24,26. Our data are in line with this, as we show that more severe anxiety, GI-specific anxiety, and non-GI somatic symptoms were associated with younger age. Interestingly, the severity of depression was not associated with age and no differences were observed between the different age groups. Quality of life was in general worse in younger patients with IBS, which is in line with existing literature2,13.

Other factors that could potentially explain decreasing severity of GI symptoms with increasing age are age-related changes in gut physiology, e.g., visceral sensory function. Visceral hypersensitivity is associated with abdominal pain intensity25,27, and a recent study has shown that visceral hypersensitivity is less common in older IBS patients14. We also observe that the low rectal sensory thresholds are stepwise increased by age groups, which are pointing towards a gradual decline in visceral sensitivity with aging in IBS. Neuroplastic or degenerative mechanisms may play a role28,29 where it is possible that visceral afferents, including the nociceptive pathways, are affected by age. Furthermore, factors involved in the central processing of visceral afferent information could also be involved, as visceral sensitivity is influenced by psychological factors in DGBI, and psychological state affects reporting of symptoms and symptom perception25,30,31,32.

Besides visceral sensitivity, we also assessed several other measures of gut physiology simultaneously, which has not been done before. Our data show that transit time in particular is associated with increasing age. Transit time was assessed with two extensively validated methods23,33,34, and a strength of our study is that both methods show similar results, that older IBS patients have slower transit when the colon is included compared with younger IBS patients. As previously mentioned, constipation seems to increase with aging, but previous studies assessing associations between colonic transit time, colonic motility, and age show no clear associations15,16,17. However, we show that transit times are longer for older IBS patients compared with IBS patients of younger and intermediate age, but no differences were observed for IBS patients of younger age versus intermediate age.

For sensorimotor function of the anorectum, we assessed resting and maximum squeeze anal sphincter pressures by using high-resolution anorectal manometry. Previous studies have shown that basal and maximum anal sphincter pressures decrease with aging, and that these changes are more pronounced in women16,17,19. Our data also show that resting anal sphincter pressures are reduced with aging, but no differences were observed for maximum anal squeeze pressures between the different age groups. An explanation for this discrepancy may be the small number of patients that completed anorectal manometry. The urine lactulose-mannitol excretion test is the optimal test to assess intestinal barrier (dys)function20, and previous studies using the same test have shown that barrier dysfunction is present in a substantial proportion of IBS patients, especially in IBS-D and post-infection IBS but less in IBS-C. Intestinal barrier dysfunction is also suggested to be associated with more severe GI symptoms, including abdominal pain35. It seems like aging does not affect intestinal barrier dysfunction in IBS, as we find no associations between age and small bowel permeability. In the current study, IBS patients of all subtypes were included and IBS subtype may be a confounding factor that could influence the results. There may be subtype-specific associations between small bowel permeability and age, but we did not perform these analyses due the expected power issues, and future studies that assess these subtype-specific associations are warranted. Moreover, intestinal barrier function was only evaluated using the lactulose/mannitol excretion test, which assesses barrier function over the entire proximal GI tract. The sensitivity of the test to detect more subtle and regional differences in permeability has not been evaluated36. However, the use of more direct tests of barrier function, such as intestinal biopsies in Ussing chambers, is not feasible in large cohort studies like ours.

Exploratory regression analyses of age, sex, psychological distress, and measures of gut physiology combined show interesting associations of specific GI symptoms and age-related changes in GI sensorimotor function but also highlight the importance of gut-brain interactions. Female sex and more severe psychological distress are independently associated with more severe abdominal bloating and GI symptoms in general. As discussed previously, psychological distress is an important factor involved in symptom reporting24,26, and highlights the importance of gut-brain interaction in IBS. We also identified female sex as an independent predictor of more severe symptoms, which is in line with previous findings. Epidemiological studies have consistently shown that IBS is more prevalent in females, and that females report more severe symptoms compared to males1,2,3,4,5,6,7. More severe psychological distress and lower rectal discomfort thresholds are independently associated with abdominal pain. As previously discussed, visceral hypersensitivity seems to gradually decrease with aging, and these results may suggest that younger IBS patients, predominantly suffering from abdominal pain, may respond better to treatments targeting psychological distress, e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy, and/or targeting visceral hypersensitivity, e.g., neuromodulators including amitriptyline, which is considered an effective treatment37. Our data also show that a slower transit is independently associated with more severe constipation. Solely slower transit was identified as a predictor of more severe symptoms in the regression model, highlighting the importance of GI motility influencing the severity of constipation. Independent of age, assessing transit time in IBS patients that experience severe constipation could be valuable and guide pharmacological management, as there are several treatments that target transit time and stool consistency. For diarrhea, more rapid transit time and psychological distress are independently associated with more severe diarrhea. Based on these data, we hypothesize that the mechanisms leading to symptoms of diarrhea are complex and including both gut motor function and gut-brain interactions. Nevertheless, assessment of transit time in IBS patients that suffer from refractory diarrhea may also be valuable to guide pharmacological management by understanding if an accelerated gut transit is a mechanism of importance on an individual basis. We show that a slower transit, a younger age, and more severe psychological distress are independently associated with more severe symptoms of satiety. Similar to constipation, transit time seems to be of particular importance for satiety symptoms, as transit time influenced the model more compared with age and psychological distress. Existing literature only report on associations between satiety and transit time in subtypes of IBS and with conflicting results that both suggest no differences in satiety between IBS subtypes, and that early satiety and abdominal fullness are more common in patients with IBS-C compared with IBS-D38,39.

Our study has a number of strengths that include the combined assessment of patient reported outcomes and measures of gut physiology in a large IBS cohort using only validated questionnaires and validated measures of gut physiology. Moreover, a comprehensive spectrum of physiologic measurements was performed, providing valuable information from different parts of the GI tract. Furthermore, the participants were not only recruited through referral from primary care to our specialized center for neurogastroenterology, but also through advertisements in (social) media. Therefore, we believe that our data to at large extent is valid for IBS patients in general. Study limitations include that we combined IBS patients with a diagnosis based on different diagnostic criteria where the Rome IV criteria is considered to define a more severe IBS phenotype40. However, our data show that severity of GI symptoms was similar regardless if Rome II, III, or IV criteria was used for the diagnosis. The cross-sectional study design makes us unable to conclude on causality of the associations. The patients were stratified, based on age, into three groups and this may have resulted in loss of valuable data. However, we decided to analyze the data with both regression models and group comparisons, and for the regression analyses, there was no loss of data. One could discuss that the cut-off of ≥ 50 years was a relatively young definition for IBS patients of older age, but this cut-off was carefully chosen, as previous epidemiological studies have shown that the incidence and prevalence of IBS, as well as severity of GI symptoms decrease at age of 50 or after mid-life1,2,4,5,22. Another reason for this cut-off is due to physiological changes associated with age, as most of the females are likely to be postmenopausal from the age of 50. The sex-specific analyses should be interpreted with caution, as this stratification resulted in lower number of subjects in the analyses, especially for males, therefore, these data may be underpowered. Another limitation is that not all subjects underwent all physiological measurements, even though we have large number of subjects for most of the measures. Like symptoms, some physiological measurements may change over time in patients with IBS. For example, studies have observed intraindividual differences in gut transit time41, and the cross-sectional study design did not allow us to take this into consideration. However, for rectal sensation, we have demonstrated in a small study that rectal hypersensitivity remained stable at the group level over 8–12 years in IBS42. We did not include other biological variables in this study, such as data on gut microbiota and metabolites, which would have provided valuable information. In addition, not all subjects underwent all physiological measurements, even though we have large number of subjects for most of the measures.

In conclusion, we demonstrate distinct age-related characteristics in IBS, as younger patients have more severe symptoms and worse quality of life, whereas older patients are less viscerally sensitive and have slower colonic transit. Age should be taken into consideration in the management of IBS, as we show that age-related differences in GI sensorimotor function may be of importance for the severity of specific GI symptoms. Furthermore, future studies in IBS should control for age, as aging is an important factor that influences both symptom reporting and the physiologic state of the gut.

Methods

Participants

Patients with IBS that completed questionnaires and/or gut physiology testing in studies of pathophysiologic mechanisms (Dnr S 489-02; Dnr 731/09; Dnr 988/14) and in intervention studies (NCT03869359; NCT02970591; NCT01252550; NCT05182593; NCT01699438; NCT02107625), were included in this retrospective cohort study (n = 1683). From the intervention studies, only baseline data were used. The inclusion period was between 2002 and 2022 at our specialized unit for neurogastroenterology at Sahlgrenska University Hospital, Gothenburg, Sweden. For the different studies, the IBS patients were recruited by any of the following: referral from primary care, self-referral, or advertisements in university buildings, newspapers or social media. IBS diagnosis was made by MS, HT, or specially trained gastroenterology residents, according to the Rome criteria at time of inclusion (Rome II, 2002–2006; Rome III, 2006–2016; Rome IV, 2016–2022)3,43,44. For all studies, exclusion criteria were severe cardiovascular, hepatic or neurological diseases, psychiatric disease being the dominant clinical problem, other GI disease explaining the GI symptoms, diabetes, GI surgery (except for appendectomy or cholecystectomy), use of antibiotics within one month before initiation of the study, pregnancy or breastfeeding. The patients gave written and verbal informed consent before any procedures were performed, and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Gothenburg approved all studies that were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki. All authors had access to the study data and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Patient reported outcomes

Severity of GI symptoms (n = 1122) was assessed by the GSRS-IBS questionnaire that consists of 13 items scored on a Likert scale from 1 (no discomfort) to 7 (severe discomfort), with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Based on the 13 items, severity of five different syndromes can be evaluated including abdominal pain, abdominal bloating, diarrhea, constipation, and satiety45. The participants also prospectively recorded stool consistency, using the Bristol Stool Form (BSF) scale46, and number of bowel movements during 14 days (n = 1427). These data were used to define IBS subtype according to the Rome III criteria.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) that consists of 14 items was used to assess psychological distress (n = 1508)47. Seven items measure symptoms of anxiety and seven items measure symptoms of depression. Each item is scored on a four-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating more symptoms of anxiety or depression.

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)-12 that consists of 12 items where each represent a specific somatic symptom was used to assess severity of non-GI somatic symptoms (n = 1161)48. Participants were asked to rate the frequency of each symptom over the past two weeks on a scale ranging from “Not bothered at all” to “Bothered a lot.” Total scores were calculated by summing the item scores, with higher scores indicating more severe somatic symptoms.

The Visceral Sensitivity Index (VSI) consists of 15 items that measure the extent to which individuals experience anxiety related to their GI symptoms and concerns (GI-specific anxiety) (n = 1223)49. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from “Not at all” to “Extremely.”

Irritable Bowel Syndrome-Quality of Life (IBS-QOL) questionnaire consists of 34 items and is a measure of health-related quality of life specifically designed for individuals with IBS (n = 968)50. It covers eight domains related to the impact of IBS on different aspects of daily life: emotional, mental, sleep, energy, physical functioning, food, social role, physical role, and sexual. Lower percentages (range 0–100) represent a worse quality of life.

Measures of gut physiology

Oro-anal transit time was assessed by use of radiopaque markers (n = 688)23,34. Ten radiopaque markers were ingested in the morning day 1–5, and 5 markers were ingested in the morning and in the evening day 6. In the morning of day 7, the number of retained markers were assessed (Fluoroscopy, Exposcop 7000 Compact, Ziehm GmbH, Nüremberg, Germany). Oro-anal transit time expressed in days was calculated by dividing the number of retained radiopaque markers by 10. No medications that could affect gut motility were allowed during the oro-anal transit time studies. The protocol of oro-anal transit time using radiopaque markers has been described and validated34,51,52. Local reference values (5th and 95th percentiles) from healthy volunteers were used to define normal oro-anal transit time: males 0.7–2.1 days; females 0.9–3.9 days23,34.

Segmental transit time was assessed using the wireless motility capsule (Smartpill®, Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) (n = 154)53. The wireless motility capsule is an ingestible, single-use, cylindrical capsule (27 × 12 mm) that measures pH (0.5–9 pH units with ± 0.5 unit accuracy), pressure (0–350 mmHg with ± 5 mmHg accuracy below 100 mmHg and 10% of the applied pressure when >100 mmHg), and temperature (20–42 °C with ± 1 °C accuracy) throughout the GI tract. Measurements of pH, pressure, and temperature are transmitted from the capsule to a data receiver that the participants wear on a belt. The data receiver stored the data with a minimum battery life of seven days. The wireless motility capsule investigation was done according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Smartpill®, Medtronic, Minneapolis, USA) and the identification of characteristic pH-landmarks defined gastric emptying time, small bowel transit time, and colonic transit time, respectively53.

Rectal sensitivity was assessed by rectal barostat (n = 623) using an electronic barostat (Dual Drive Barostat Distender, Distender Series II; G&J Electronics, Toronto, Ontario, Canada); and with two different protocols54,55. In both protocols, participants were positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, and a latex balloon was inserted into the rectum and linked to a barostat device. Gradually increasing pressures were applied through sequential distensions, and participants were directed to provide sensory thresholds, including first sensation, urge to defecate, discomfort, and pain. The sensory intensity ratings were obtained to assess rectal sensitivity. In protocol 1 we used phasic distensions, where participants first received a habituation sequence, followed by determination of the operating pressure, i.e., 2 mmHg above the minimal distending pressure necessary to record respiratory variations in balloon volume. Next, phasic distensions (an ascending methods of limits paradigm) of 30 seconds were performed, separated by 30 seconds rest intervals at the operating pressure. The distensions were applied with 5 mmHg stepwise increments, starting at the operating pressure and increasing until the participant reported pain or the pressure of 70 mmHg was reached. In protocol 2 we used a distension paradigm with ramp inflation. Here, the participants also received a habituation sequence followed by determination of the operating pressure. Next, sensory thresholds were measured by ramp inflation, starting at 0 mmHg and increasing in steps of 4 mmHg for 1 minute per step to a maximum of 60 mmHg. To combine these data, we calculated Z-scores based on sensory thresholds (mmHg).

Anal sphincter function was assessed by high-resolution anorectal manometry (n = 190)56. The participants were positioned in the left lateral decubitus position, and a solid-state catheter with pressure sensors (Manoscan AR Catheter Regular, Given Imaging Inc, USA) was inserted into the rectum. After allowing for acclimatization, resting anal sphincter pressure was measured by calculating the mean pressure during a 1-minute resting period, while maximum anal squeeze pressure was determined by measuring the peak pressure generated during three maximal voluntary squeeze efforts. The analysis was primarily performed by automated software system (ManoView AR v3.0, Medtronic Inc, USA), and if needed manually adjusted using the e-sleeve function by reviewer (AB) to fit area of interest. Data points were thereafter extracted from the program.

Small bowel permeability (n = 136) was assessed using the urine lactulose-mannitol excretion test36,57,58. After voiding their bladder, participants ingested 150 ml of a solution containing 5 g lactulose and 1 g mannitol, after which urine was collected for 2 hours59. The total urine volume was noted and 1.5 ml sample aliquots were filtered through 0.45 μm filters and stored at −20 °C until further analysis. The concentrations of lactulose and mannitol in the urine samples were quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography – evaporative light-scattering detector (HPLC-ELSD), as described by us previously60, and the lactulose-to-mannitol ratio was calculated as a measure of small bowel permeability, with higher ratios indicating increased permeability.

Data analysis

Demographic and characteristics were presented for the whole study population and divided by the different Rome criteria. Data were tested for normality (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test) and all analyses were done using the whole study population. First, linear regression models were used to assess the associations between age (independent variable) and patient reported outcomes and measures of gut physiology (dependent variables) in separate models, assessing the strength and direction of the associations. All analyses were controlled for sex. The variable ‘duration of IBS (years)’ was initially added to all models but did not influence the outcomes. Therefore, ‘duration of IBS (years)’ was later removed from all models. Second, IBS patients were stratified into groups based on age: younger, 18–29 years, intermediate age, 30–49 years, and older, ≥50 years. ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis tests with pairwise comparisons (Bonferroni correction for post-hoc analyses) were used to assess differences between the age groups. Third, linear regression analyses were used to explore if age, sex, psychological distress, and measures of gut physiology combined (independent variables) were associated with severity of GI symptoms (dependent variables). In these analyses, the different measures of transit time and rectal sensitivity were included, as previous studies have highlighted the association of these aspects of GI symptom severity23,25,61. Multicollinearity was excluded before these analyses, using Spearman r > 0.7 as cut-off. Data are presented as frequencies (n and/or %), mean ± SD, mean with 5th and 95th percentiles or β-coefficients with S.E. and 95% CI, and R2 values were presented for regression analyses. P values < 0.05 (two-tailed) were considered as statistically significant, and all statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism version 10.0.0 (GraphPad Software, Boston, Massachusetts, USA).

Responses