DJK-5, an anti-biofilm peptide, increases Staphylococcus aureus sensitivity to colistin killing in co-biofilms with Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Introduction

Chronic bacterial infections are a major issue worldwide, increasing in prevalence and severity, leading to a burden on healthcare systems1. Approximately 80% of chronic infections are associated with biofilms2. Biofilms are a population of bacteria encased within an extracellular matrix which protects them from environmental stressors and antimicrobial treatment3. Biofilm-associated infections are often polymicrobial in nature, including a combination of Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, and depending on the infection site, fungi4. Infections that are associated with biofilms are complex, harder to treat, and associated with worse patient outcomes5,6,7. Co-infections of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus are prominent in wound infections8, otitis media9, and the lungs of individuals with cystic fibrosis10.

Current methods for treating biofilm-associated infections in chronic wounds involve the physical removal of the biofilms by debridement and drainage of the infected site in combination with antibiotic treatment11,12. Treatments for biofilm-associated lung infections with P. aeruginosa include inhaled antibiotics tobramycin or aztreonam13,14. For chronic S. aureus infection within the lung of CF patients’, treatment includes inhaled vancomycin or fosfomycin15,16. Despite the increasing evidence of co-infection with P. aeruginosa and S. aureus in respiratory infections, chronic wounds, and bloodstream infections, current treatment methods often only target Gram-negative bacteria and are ineffective against Gram-positive bacteria, and vice versa. Last resort antibiotics are often narrow spectrum and target primarily Gram-negative or Gram-positive organisms. For instance, the two lipopeptide antibiotics, colistin (polymyxin E) and daptomycin, have distinct mechanisms of action and exhibit strong activity against Gram-negative17,18 and Gram-positive bacteria19, respectively. Polymyxins bind to the lipopolysaccharide component lipid A and displace the divalent cations magnesium and calcium. This causes uptake of polymyxin and interaction with the cytoplasmic membrane where its mechanism is less certain20,21. Daptomycin inserts into the cytoplasmic membrane via calcium-dependent integration. This process leads to rapid disruption and depolarisation of the membrane, as well as inhibition of other functions, without causing lysis22,23,24,25.

Polymyxins are considered ineffective against Gram-positive bacteria where the intrinsic resistance mechanism may be due to unfavourable binding to the lipoteichoic acids in the cytoplasmic membrane (i.e., colistin cannot attach to the cell to displace cations, causing leakage)26. However, recent studies have demonstrated that colistin exhibited non-canonical activity against Gram-positive organisms Paenibacillus polymyxa and Bacillus subtilis. This activity of colistin enhanced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) metabolism, leading to an increase of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and eventually cell death27. Rudilla et al. have further shown the chemical synthesis of colistin derivatives with antimicrobial activity against S. aureus28. Additionally, unlike other antibiotics, colistin has been shown to be effective against metabolically inactive biofilm-embedded cells located within the innermost layers of the biofilm29.

To reduce the rise of antibiotic resistance, new strategies to combat biofilm-associated infections include combination treatment with two antibiotics, or novel combinations of antibiotics with antimicrobial peptides (AMPs). DJK-5, a D-enantiomeric peptide with strong anti-biofilm activity30, has efficacy against multiple pathogens in vitro and in vivo30,31,32,33,34. Moreover, DJK-5 has shown synergistic activity when coupled with traditional antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin against P. aeruginosa LESB58 and vancomycin against S. aureus USA300 LAC35. The clear mechanism of this synergistic activity remains to be elucidated. However, there is evidence that DJK-5 treatment leads to the permeabilization of the bacterial membrane barrier resulting in leakage of intracellular materials and enhanced uptake34. Another proposed mechanism of DJK-5 against biofilm-associated cells is targeting and degradation of the signalling molecule ppGpp, a crucial component for the stringent stress response (SSR). Targeting ppGpp results in impaired formation and maintenance of biofilms and decreased abscess formation30,33. The SSR in bacteria is broadly conserved amongst all bacterial species, important for the control of adapting to stress, including nutrient deprivation, oxidative stress, biofilm formation, and virulence36,37.

Given that P. aeruginosa can protect S. aureus from antibiotic treatment via biofilm formation and siderophore production38,39, we investigated whether peptide DJK-5 could sensitize S. aureus to colistin treatment within co-biofilms. Using both a host-mimicking, co-culture static biofilm model and a murine, biofilm-like skin co-infection model, our study presents evidence that S. aureus can become vulnerable to treatment with normally selective antibiotics.

Results

Colistin combined with DJK-5 showed additive activity against P. aeruginosa LESB58 and S. aureus USA300 LAC in host-mimicking conditions

The impact of the host environment on drug susceptibility underscores the importance of considering host-specific factors in assessing therapeutic outcomes40,41. We previously demonstrated the enhanced synergistic activity of azithromycin with D-enantiomeric peptide DJK-5 and polycationic lipopeptide antibiotic colistin, respectively, under physiologically relevant conditions against P. aeruginosa42. This prompted us to further investigate whether host-mimicking conditions (tissue culture medium supplemented with foetal bovine serum; DFG) similarly affect antimicrobial activity against Gram-positive S. aureus.

S. aureus is resistant to colistin with MIC values of >100 µg/mL in MHB and 250 µg/mL in DFG. But intriguingly, the antimicrobial activity of anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5 against S. aureus increased in DFG by 4-fold (25 µg/mL to 6.25 µg/mL) (Table 1). Both colistin and DJK-5 showed decreased activity (2- to 4-fold) in DFG against P. aeruginosa as previously42.

We further determined the combinatorial effects of colistin and DJK-5 (Table 1), and daptomycin with DJK-5 (Supplementary Table 1). Colistin/DJK-5 synergized against P. aeruginosa in MHB (FICI of 0.5) but was only additive in host mimicking conditions. Interestingly, colistin combined with DJK-5 also showed additive activity against S. aureus in DFG (FICI of 0.75). This unexpected combinatorial effect highlights the potential for combination therapy as a strategic approach in combating S. aureus infections and warrants further investigation.

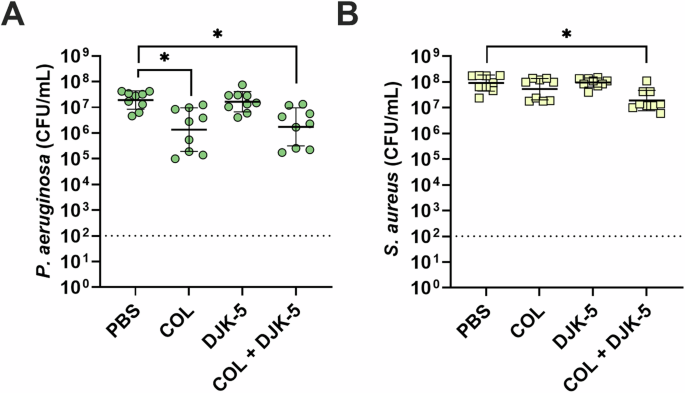

Peptide DJK-5 is a potent anti-biofilm peptide with broad-spectrum activity and synergizes with conventional antibiotics against biofilms30,43. To test whether this would also apply to the lipopeptide antibiotic colistin, we investigated their combinatorial activity against mature biofilms of P. aeruginosa, S. aureus and both grown together. Based on the additive activity of colistin/DJK-5 in DFG (Table 1), we developed a static biofilm model using tissue culture medium, showing about 107-108 CFU/mL being present after three days (Fig. 1). P. aeruginosa LESB58 biofilms treated with a high colistin concentration (125 μg/mL; 10 × MIC in DFG) significantly reduced bacteria within monomicrobial biofilms by more than one log (15-fold) (Fig. 1A). DJK-5 did not show activity under monomicrobial conditions in our static biofilm model and did not synergize with colistin. This correlates with our observation under planktonic conditions using DFG, which could potentially be due to the loss of activity in physiologically relevant media. As expected, colistin even at a concentration of up to 125 μg/mL, was ineffective against S. aureus biofilms (Fig. 1B). DJK-5 did not eradicate S. aureus biofilms in this model but, interestingly, it showed a minor, although significant, reduction of bacterial numbers by 0.5-log (5-fold) when combined with colistin. This combinatorial effect was also observed in the presence of sub-lethal exposure of oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide, H2O2) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

P. aeruginosa (A, green circles), S. aureus (B, yellow squares). biofilms were treated with colistin (125 μg/mL), DJK-5 (50 μg/mL) alone and in combination after three days. Bacterial survivors (CFU/mL) were determined on selective agar plates on day four. Each dot represents one experiment with geometric mean ± geometric standard deviation (n =9). Statistical analyses were performed using a One-way ANOVA compared to the PBS control using the Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction. Asterisks indicates significant differences (*p < 0.05). Dashed line represents limit of detection.

Colistin combined with DJK-5 exhibited synergistic activity against co-biofilms of P. aeruginosa-S. aureus

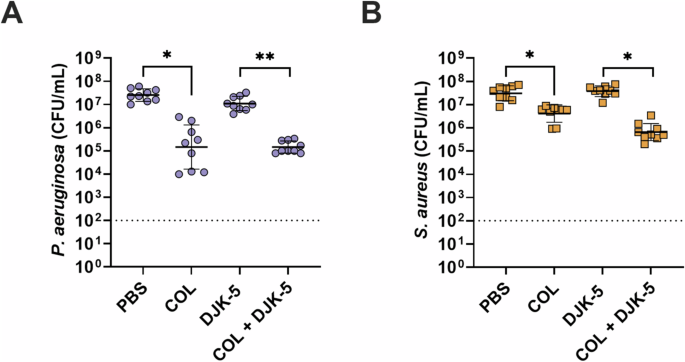

Given the frequent co-isolation of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus from cystic fibrosis airways and chronic wounds44,45, we further refined our host-mimicking biofilm model to allow for the co-existence of both bacteria at a concentration of ~107 CFU/mL over several days (Fig. 2). Individual treatment with colistin showed a significant ~1.6-log (40-fold) reduction in bacterial survivors against P. aeruginosa (Fig. 2A), while DJK-5 had a modest activity. Against S. aureus, colistin had no effect, but DJK-5 reduced CFUs by 1.6-log (40-fold) (Fig. 2B). Remarkably, when combining colistin with DJK-5, we observed a significant synergistic reduction (predictive additive effect – PAE) compared to the CFU counts obtained by the drug combination) of both P. aeruginosa (~2.8-log, 700-fold) and S. aureus (~1.4-log, 28-fold) compared to DJK-5 treatment alone. This reflected an overall ~3.0-log (1,050-fold) reduction of S. aureus and a ~3.3-log (2,140-fold) reduction in P. aeruginosa bacteria compared to no treatment. A similar, significant reduction in P. aeruginosa and S. aureus survival was observed when combining a 20 times lower concentration of colistin (6.25 µg/mL) with DJK-5 (Supplementary Fig. 2). Similarly to monomicrobial biofilms the combination treatment with the addition of H2O2 was also synergistic against co-biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 3).

P. aeruginosa (A, purple circles), S. aureus (B, orange squares). Co-biofilms were treated with colistin (125 μg/mL), DJK-5 (50 μg/mL) alone and in combination after three days. Bacterial survivors were determined on selective agar plates (CFU/mL). Each dot represents one experiment with geometric mean ± geometric standard deviation (n = 8). Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). The predicted additive effect (PAE) was determined by the sum of CFU log reduction obtained for each single treatment and a Mann-Whitney test performed to compare PAE to the CFU counts obtained by the drug combination; ⊕ p =<0.05 is synergistic. The dashed line represents limit of detection.

Inducing stringent stress response attenuated the combinatory effect of colistin and DJK-5 against S. aureus in co-biofilms

Previously, de la Fuente-Núñez et al. demonstrated that DJK-5 prevented the accumulation of the intracellular stringent stress response signalling molecule ppGpp30,33. Here, we exposed biofilms to 1 mmol of serine hydroxamate (SHX) to induce increased ppGpp production an hour prior to treatment with colistin, DJK-5, or a combination of both. While we found no significant difference in survival for P. aeruginosa in co-biofilm controls (~3.2 × 107 CFU/mL), the addition of SHX resulted in slightly higher survival for S. aureus in co-biofilm controls (2.5 × 107 CFU/mL) compared to no SHX (1.4 × 107 CFU/mL). A direct comparison of the data presented in Figs. 2 and 3 is provided in Supplementary Fig. 4.

P. aeruginosa (A, purple circles), S. aureus (B, orange squares) biofilms were treated with colistin (125 μg/mL), DJK-5 (50 μg/mL) alone and in combination. Bacterial survivors were determined on selective agar plates (CFU/mL). Each dot represents one experiment with geometric mean ± geometric standard deviation is shown. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). Dashed line indicates limit of detection.

DJK-5 activity was abolished against both pathogens in the presence of SHX. Similarly, the combination of DJK-5 and colistin was also less effective upon SHX treatment, resulting in a significant >10 times higher survival of both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus (Supplementary Fig. 4). The synergistic effect of colistin and DJK-5 was not observed when cells were induced with SHX, likely due to the partial inactivation of DJK-5.

These same conditions against monomicrobial biofilms showed the same response as biofilms treated without the presence of SHX (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Secreted factors did not account for the combinatorial effect of colistin with DJK-5

Given the observed combinatorial effect of colistin and DJK-5 against co-biofilms, we hypothesized that P. aeruginosa might produce a secreted factor that enhances the susceptibility of S. aureus. To test this hypothesis, we treated biofilms with the addition of 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline-N-oxide (HQNO), a potent quorum-sensing molecule known to be directly involved in P. aeruginosa-mediated killing of S. aureus within biofilms46,47,48. However, the addition of exogenous HQNO did not increase susceptibility to colistin and DJK-5 in monomicrobial biofilms of either P. aeruginosa or S. aureus (Supplementary Fig. 6A, B). Furthermore, HQNO did not induce increased killing within co-biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 6C, D).

To confirm there were no other secreted factors produced by P. aeruginosa in co-biofilms that could elicit this effect, we added concentrated co-biofilm supernatant at the time of treatment with colistin, DJK-5, or their combination. The addition of concentrated biofilm supernatant did not increase the efficacy of treatment against monomicrobial biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 7A, B) nor against co-biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 7C, D).

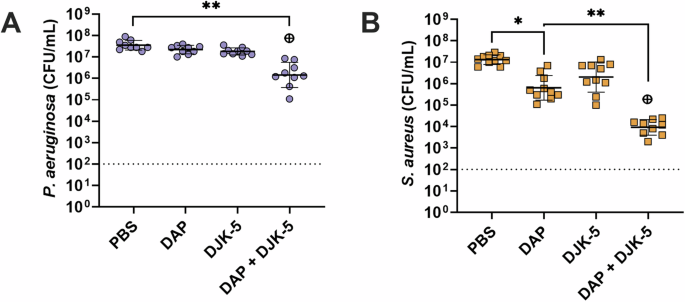

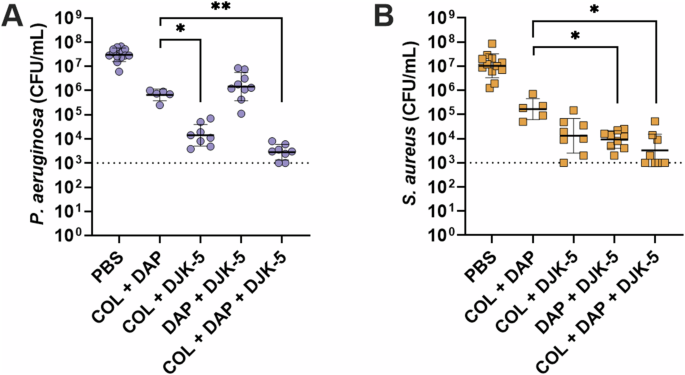

The Gram-positive bacteria targeting antibiotic daptomycin showed activity against P. aeruginosa in co-biofilms when used in combination with DJK-5

Given colistin’s lack of activity against S. aureus, we aimed to explore the potential of inducing similar activity using a traditionally Gram-positive antibiotic against Gram-negative P. aeruginosa. The lipopeptide antibiotic daptomycin was used in the same way colistin was tested (by itself and in combination with DJK-5). As expected, daptomycin (10 μg/mL, 10 × S. aureus MIC) showed no activity against P. aeruginosa monomicrobial biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 8A) and high activity against S. aureus monomicrobial biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 8B, 1.7-log (55-fold) reduction), with the combination of daptomycin and DJK-5 showing no synergistic activity. Remarkably however, the combination of daptomycin and DJK-5 showed a significant ~1.5-log (30-fold) decrease in survival compared to the individual treatments against P. aeruginosa within co-biofilms (Fig. 4A). Additionally, there was a synergistic effect between daptomycin and DJK-5 against S. aureus in co-biofilms with the combination showing a 1.9-log (80-fold) decrease in survival when compared to either daptomycin, or DJK-5 treatment alone (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, combinations of colistin and daptomycin showed no significant synergistic effect for monomicrobial biofilms of P. aeruginosa or S. aureus (Supplementary Fig. 8). There was also no significant synergism between colistin and daptomycin against co-biofilms of P. aeruginosa and S. aureus (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. 9)

P. aeruginosa (A), S. aureus (B). Biofilms were treated with daptomycin (10 μg/mL), DJK-5 (50 μg/mL) alone and in combination. Bacterial survivors were determined on selective agar plates (CFU/mL). Each dot represents one experiment with geometric mean ± geometric standard deviation is shown. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). The predicted additive effect (PAE) was determined by the sum of CFU log reduction obtained for each single treatment and a Mann-Whitney test performed to compare PAE to the CFU counts obtained by the drug combination; ⊕ p =< 0.05 is synergistic. The dashed line represents the limit of detection.

P. aeruginosa (A), S. aureus (B). Biofilms were treated with daptomycin (10 μg/mL), DJK-5 (50 μg/mL), or colistin (125 μg/mL) alone and in combination. Bacterial survivors were determined on selective agar plates (CFU/mL). Each dot represents one experiment with geometric mean ± geometric standard deviation shown. Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

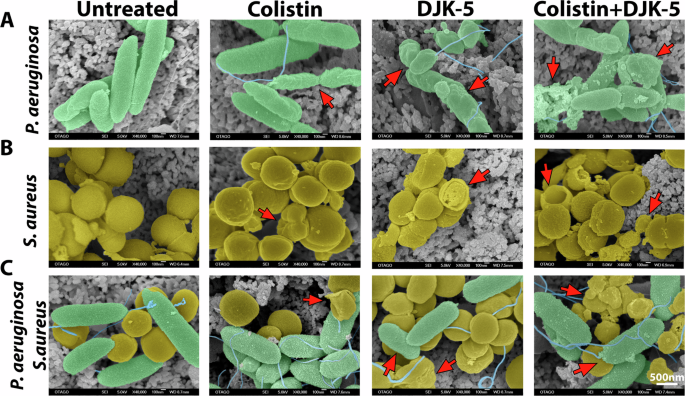

Colistin combined with DJK-5 caused cell deformation of both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus within co-biofilms

We have previously shown that biofilms treated with DJK-5 led to tube-like blebbed structures with shrinkage in cell morphology in P. aeruginosa and enlarged S. aureus cells with a rough cell surface morphology43. Here, we further investigated morphological changes on the cell surfaces of co-biofilms upon treatment with colistin, DJK-5, or both. We used a low concentration of colistin (6.3 µg/mL) to treat monomicrobial P. aeruginosa biofilms (Fig. 6A) and a higher concentration of colistin (125 µg/mL) to treat monomicrobial S. aureus biofilms (Fig. 6B) and co-biofilms (Fig. 6C). Upon treatment of P. aeruginosa monomicrobial biofilms with either colistin or DJK-5, we found bacterial cells that were significantly smaller, appearing as short rods (Fig. 6A, Supplementary Fig. 10). The combinatorial treatment of colistin and DJK-5 led to changes to the surface morphology of P. aeruginosa surface, indicating membrane damage (Fig. 6A). In contrast, S. aureus cells treated with individual compounds and the combination, led to minimal surface changes, however, cell area was significantly reduced, and cells showed a higher prevalence of wrinkled damaged membrane (Fig. 6B, Supplementary Fig. 10).

(A) Monomicrobial P. aeruginosa (green) biofilm was treated with colistin (6.3 μg/mL), DJK-5 (40 μg/mL) and combination of both. (B) Monomicrobial S. aureus (yellow) biofilm treated with colistin (125 μg/mL) DJK-5 (40 μg/mL), and the combination of both. (C) Co-biofilms treated with colistin (125 μg/mL), DJK-5 (40 μg/mL) and a combination of both. Biofilms were fixed, washed, dehydrated, and coated approximately 25 nm AuPd and imaged by SEM. Arrows indicate cell membrane damage and cellular debris. The scale bar applies to all images in this figure (n = 4 replicates / 6 images per replicate), unmodified SEM image is shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

In co-biofilms, both bacteria co-localized in close interaction on the surface (Fig. 6C). Individual treatment with colistin exhibited similar effects on P. aeruginosa cells where the surface showed a crumbled phenotype while S. aureus surface integrity was maintained (Fig. 6B). DJK-5 treated co-biofilms led to shorter P. aeruginosa rods where S. aureus cells appear wrinkled and less cocci-shaped. The combined treatment led to more visible debris where both P. aeruginosa rods and S. aureus cocci cells exhibited a crumbed, wrinkled appearance (Fig. 6C).

Membrane leakage in co-biofilms indicated the synergistic bactericidal effect of colistin and DJK-5 against S. aureus

Given the prevalence of deformed and damaged cells observed through SEM in biofilms treated with colistin and DJK-5, we employed a codon optimized LacZ49,50-producing strain of S. aureus USA300 LAC to enzymatically assay the presence of free LacZ in the supernatant of biofilms post-treatment, indicative of membrane damage and cell lysis. Three-day-old biofilms comprising P. aeruginosa LESB58 and S. aureus USA300 LAC::pJB185sarAP1 were treated with colistin, DJK-5, or their combination and the relative amount of LacZ in the supernatant was assayed using ONPG49. Consistent with CFU determination (Fig. 1B), a modest increase in LacZ release was observed when monomicrobial S. aureus biofilms were treated with the colistin and DJK-5 combination (Supplementary Fig. 12A). Remarkably, in co-biofilms with P. aeruginosa, there was a significant 25-fold increase in the relative amount of LacZ in the biofilm supernatant following treatment with DJK-5 alone and a 35-fold increase in combination with colistin and DJK-5 (Supplementary Fig. 12B).

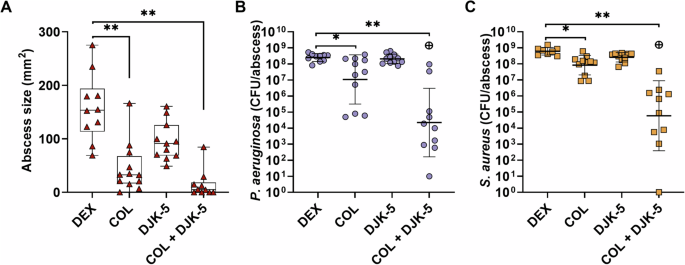

Colistin combined with DJK-5 demonstrated synergistic efficacy against co-infections within cutaneous abscesses in vivo

The treatment of chronic infections such as lung infections in CF patients, chronic wounds, and chronic otitis suppurative media remains challenging51. To further investigate the combinatorial activity of colistin and DJK-5 against co-infections caused by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus, we adapted our mono-microbial high-density (biofilm-like) murine skin abscess model51. We chose P. aeruginosa LESB58 due to its well-documented characteristics of chronic infection. It is also known for its decreased motility due to reduced flagella production, a common adaptation for chronic growth in the CF lung52,53. Chronic wounds, like CF lungs, present a persistent inflammatory environment where P. aeruginosa can establish long-term infections54. The ability of LESB58 to thrive in chronic conditions without dissemination aligns with the infection dynamics observed in chronic wounds, making it a relevant model for our studies.

Colistin treatment alone significantly reduced the size of co-infected abscesses by 75% when compared to the dextrose control. Promisingly, combinatorial treatment with DJK-5 further enhanced the anti-abscess activity, reducing abscess infection sizes by 98% (Fig. 7A). Similar to the anti-abscess activity, we found that colistin alone significantly reduced both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus survival by ~1.5-log (30-fold) and 1-log (10-fold), respectively (Fig. 7B,C). DJK-5 showed a visual reduction of abscess lesions but did not exhibit any antimicrobial activity against P. aeruginosa or S. aureus at the given concentration (3 mg/kg). The combinatorial treatment of colistin and DJK-5, however, significantly reduced both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus survivors by ~4-log (11,000-fold) and ~3.5-log (3,000-fold) respectively compared to the control. Overall, the combination significantly reduced P. aeruginosa and S. aureus survivors by ~2.5-log (300-fold) compared to the treatment with colistin alone. A less pronounced effect was observed when mice were treated as above although with daptomycin (2.5 mg/kg) in replace of colistin. Daptomycin and the combination of daptomycin and DJK-5 significantly reduced abscess size (Supplementary Fig. 13A). Daptomycin treatment resulted in a 1-log (10-fold) reduction in P. aeruginosa survival and a ~ 3.4-log (2600-fold) reduction in S. aureus (Supplementary Fig. 13B, C). The combination of DJK-5 and daptomycin enhanced the efficacy of treatment showing a significant PAE and a ~ 2.4-log (250-fold) and ~4.5-log (32,000-fold) reduction in survival for P. aeruginosa and S. aureus respectively (Supplementary Fig. 13B, C).

Mice were subcutaneously injected with ~2.5 × 107 CFU of each P. aeruginosa and S. aureus and treated with dextrose (Dex), colistin (2.5 mg/kg), DJK-5 (3 mg/kg) or a combination of both one hour later. After three days, mice were euthanized, abscesses were measured (A, red triangles) and then collected for bacterial enumeration of P. aeruginosa (B, purple circles), and S. aureus (C, orange squares) on selective agar plates. Each dot represents one mouse with geometric mean ± geometric standard deviation (n = 10-11). Statistical analyses were performed using a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. Asterisks indicate significant differences (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01). The predicted additive effect (PAE) was determined by the sum of CFU log reduction obtained for each single treatment and a Mann-Whitney test performed to compare PAE to the CFU counts obtained by the drug combination; ⊕ p =< 0.05 is synergistic.

Discussion

The complex crosstalk between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus within biofilms elicits antimicrobial tolerance and resistance, posing difficult challenges in therapeutic intervention8,46. Given the hurdles associated with combating polymicrobial biofilm infections55,56,57 there is a need to explore new therapeutic avenues.

In certain scenarios, it has been shown that the co-administration of antibiotics can re-sensitize resistant bacterial strains. For example, synergy has been shown when colistin is combined with other antibiotics, such as clofoctol, a synthetic antibiotic used against Gram-positive bacteria, by inhibiting cell wall synthesis and inducing membrane permeabilization58. This combination exhibited synergy against a collection of colistin-resistant Gram-negative bacteria, including clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa, K. pneumoniae and A. baumannii59. However, limited research has been conducted regarding the potential of lipopeptide polymyxins in combination with other antimicrobials, especially against Gram-positive pathogens. In a recent study by Si et al., it was demonstrated that colistin enhanced S. aureus susceptibility to the polypeptide antibiotic bacitracin60, likely due to increased cell wall permeability enhancing polymyxin uptake into the cell membrane. Conversely, another study by Choi et al.61 showed antagonistic interaction between colistin and glycopeptide vancomycin against S. aureus, in both in vitro and in vivo settings. Both studies were conducted against S. aureus alone and in nutrient-rich planktonic cultures and the underlying mechanisms were not determined. It is widely acknowledged that the host environment can significantly influence bacterial virulence62 and antibiotic efficacy63. Consequently, there is a growing recognition that evaluating novel compounds and antibiotic combinations in conditions mimicking the host environment hold greater clinical relevance63,64.

We previously showed that polymyxin B synergized with the antimicrobial peptide LL-37 against E. coli and P. aeruginosa65. Building upon these findings and considering the promising outcomes of lipopeptide and polypeptide combinations58,59,60, prompted us to further investigate a combination of colistin with the D-enantiomeric anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5 against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Both colistin and DJK-5 are cationic, facilitating their binding to negatively charged lipopolysaccharide (LPS). In our study, we used tissue culture medium supplemented with foetal bovine albumin, which is known to bind to colistin66. In addition, albumin binds multiple different antimicrobial peptides, inhibiting their activity. This may contribute to the observed reduction in antimicrobial activity and synergy against P. aeruginosa67.

S. aureus has been shown to lower the pH under high glucose conditions through the fermentation of glucose and secretion of lactate and acetate68. Under low pH conditions, albumin undergoes conformational changes losing its anionic properties69. The enhanced activity of DJK-5 against S. aureus in vitro may therefore, at least partially, be attributed to the slightly acidic environment in our culture conditions (based on the phenol red pH indicator in tissue culture medium changing from red to yellow). Thus, the net positive charge of DJK-5 could potentially be increased, as shown previously with peptidomimetic peptoids70,71. This positive charge could potentially enhance interactions with polyanionic components such as lipoteichoic acids and teichoic acids.

Interactions between P. aeruginosa and S. aureus frequently alter the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of both bacterial species. We found that in a co-microbial environment, P. aeruginosa enhances the susceptibility of S. aureus to the anti-biofilm peptide DJK-5, while S. aureus appears to protect P. aeruginosa against colistin. This protection is likely due to factors such as altered nutrient utilization, pH changes, and secreted compounds such as staphylococcal protein A (SpA), which binds to the P. aeruginosa cell surface and may enhance antimicrobial tolerance72. This protective effect is supported by studies showing SpA contributes to antibiotic tolerance in polymicrobial biofilms39. Intriguingly, the combination of colistin and DJK-5 exhibited synergistic activity against both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus within our co-microbial setting (Fig. 2). Jorge et al.73 previously showed that combinatory treatments of colistin with other AMPs such as temporin-A, citropin 1.1, and tachyplesin I linear analogue displayed additive and synergistic activity against both mono- and co-microbial biofilms formed by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Our findings contribute additional evidence supporting efficacy of anti-biofilm peptides in polymicrobial environments.

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the synergistic activity of colistin and DJK-5, we examined bacterial cell surface morphology for evidence of membrane damage and assessed overall biofilm disruption activity. Using a three-day, static biofilm model grown on hydroxyapatite discs, we tested the anti-biofilm activity against biofilms formed by S. aureus and P. aeruginosa individually, as well as in co-culture. Colistin exhibited pronounced membrane-damaging activity against P. aeruginosa inducing a reduction in cell length (Supplementary Fig. 10A, B), but had minimal effects on S. aureus, as expected (Fig. 6, Supplementary Fig. 10C, D). However, we were intrigued by the studies of Yu et al.27,74, that demonstrated that colistin disrupts cell membranes and induces surface alterations in its producer bacterium P. polymyxa, which they attributed to NADH metabolism leading to the generation of ROS. Additionally, Shah et al. 75 showed that P. aeruginosa can damage S. aureus cell membranes through ROS generation. We also recently reported the superior biofilm eradication and membrane-damaging activity of DJK-5 against individual P. aeruginosa and S. aureus biofilms grown on an air-liquid interface human skin model43. Thus, we hypothesized that combining colistin with DJK-5 could induce cellular damage under co-microbial conditions. Indeed, within the co-microbial environment we observed increased cell wall damage and debris, suggesting that both colistin and DJK-5 combine to act on P. aeruginosa and S. aureus cell membranes. This was reflected in the significant reduction in cell area for S. aureus and cell length for P. aeruginosa (Supplementary Fig. 10). The crumbled and wrinkled phenotypes observed in our SEM studies indicate biofilm matrix disruption and structural collapse. These changes suggest DJK-5 treatment causes damage to bacterial cell walls and membranes, reducing biofilm matrix and leading to cell lysis and debris formation30,43. Wang et al.34 have previously demonstrated DJK-5 destroys the integrity of bacterial membranes and leads to cell leakage. This disruption enhances bacterial susceptibility to further treatments, aligning with previous findings on antibiofilm peptide efficacy76,77. This effect may be attributed to the rearrangement of electric charges on the cell surface, as previously shown by Si et al. using colistin and bacitracin60 or to enhanced perturbation of the inner membrane which is the site of cell wall precursor addition. To further investigate whether membrane perturbations were induced by the combination treatment of colistin and DJK-5, we quantified extracellular LacZ activity from S. aureus (Supplementary Fig. 12). In both monomicrobial and co-biofilms, the combination treatment resulted in a significant increase in LacZ activity, indicating that membrane damage induced by the treatment leads to leakage from the cell membrane. This suggests that colistin and DJK-5 are not primarily synergizing to reduce biofilm formation but rather to cause cell membrane damage and subsequent cell death in S. aureus within co-biofilms. It was also shown that the addition of SHX could partially diminish the efficacy of DJK-5 in S. aureus biofilms (Supplementary Fig. 4B). This is likely through SHX increasing accumulation of ppGpp within the cell, which has been shown to interact with DJK-5. Although recent research has indicated that ppGpp null mutants of both P. aeruginosa and S. aureus are more susceptible to DJK-5, suggesting that ppGpp provides a protective effect on the cells during DJK-5 treatment33,78. It has been observed that DJK-5 can increase the pH within oral biofilms and directly reduce biofilm exopolysaccharide abundance79. This effect could also be occurring in our co-biofilms, although further study would be required.

Interestingly, we observed similar combinatorial activity when daptomycin and DJK-5 were combined against co-microbial biofilms (Fig. 4) and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 13), although there was no synergistic activity between them. These findings indicate that DJK-5 holds promise as an adjuvant therapy (Fig. 5, Supplementary Figs. 8-9). We further hypothesize that colistin and daptomycin enhance the uptake of DJK-5 into S. aureus and P. aeruginosa cells, however, further investigation is warranted in future studies.

DJK-5 has been shown to promote the degradation of the stringent response signalling molecule guanosine tetraphosphate (ppGpp), resulting in biofilm disruption33,35. To test if ppGpp signalling could be the means by which we observe synergistic activity between colistin and DJK-5, we induced excessive stringent stress response to elevate intracellular ppGpp levels. Remarkably, this resulted in reduced killing of S. aureus within co-biofilms (Fig. 3B), although it seemingly did not fully account for the synergistic effect. Thus, targeting stress-related responses in conjunction with membrane-damaging agents presents a promising novel therapeutic approach against complex infections caused by multiple pathogens.

To explore the therapeutic potential of this drug combination, we optimized our murine skin infection model51 to enable co-infection by both organisms32. Much like in vitro co-biofilms, within our murine model we observed substantially enhanced synergistic killing with colistin and DJK-5 (Fig. 7). This led to significant reductions in abscess size and dermonecrosis (Fig. 7A). During infection, ROS are generated by the host immune system’s phagocytes, including macrophages and neutrophils, to eliminate pathogens and protect against infection80. We have previously demonstrated that rapid recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the inflammatory site during P. aeruginosa infection81, with peak reactive species production within the initial three hours post infection. Consistent with our in vitro findings using co-biofilms, the combination of colistin and DJK-5 significantly reduced bacterial survival in abscess infections in vivo. Furthermore, colistin alone and in combination with DJK-5 significantly decreased abscess sizes and effectively killed both bacteria within the infection.

Our research underscores the potential of combining lipopeptides with an anti-biofilm peptide that targets cell membranes and stringent stress response as a promising new treatment approach against co-biofilm-associated infections caused by P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics like colistin or daptomycin, which lack antimicrobial activity against certain pathogens, can still be utilized in combination with other antimicrobials. The co-administration of colistin with an anti-biofilm peptide may also enable the reduction of colistin dosage, mitigating its nephrotoxic effects.

Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

Bacterial strains P. aeruginosa LESB5882 and S. aureus USA300 LAC83 were grown at 37°C on LB agar for 12–18 h.

Antimicrobial activity of colistin and DJK-5

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of colistin and DJK-5 were determined using the broth microdilution method84 in Greiner bio flat chimney polypropylene 96-well plates using Mueller Hinton Broth (MHB; Oxoid) and DMEM-FBS-Glucose (DFG; DMEM (Gibco’s Dulbecco’s minimal Eagle’s medium; Thermo Fisher) supplemented with 5% foetal bovine serum (FBS; NZ source) and 1% glucose. All tests were performed at least in triplicate following the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines85. Bacterial growth was visually examined after 18-24 h incubation (37 °C). The fractional inhibitory concentration indices (FICI)86 were determined by a synergy checkerboard assay where P. aeruginosa and S. aureus were exposed to a combination of colistin and DJK-5 in MHB. The FICI was determined by the formula [MIC of colistin in combination]/MICcolistin + [MIC of DJK-5 in combination]/MICDJK-5. FICI values represent synergy: ≤0.5, additive: >0.5 – 1, indifferent: >1 – 4, antagonistic: >486.

Biofilm colony forming units and synergistic activity

P. aeruginosa and S. aureus monomicrobial and co-biofilms were grown for three days in 24 well plates in DFG. Bacteria were prepared in 1 × PBS at 2 × 107 P. aeruginosa and 2.5 × 107 S. aureus to form monomicrobial biofilms and mixed 1:1 to form co-biofilms. The media was changed daily. After 72 h, biofilms were treated with either 6.3 μg/mL or 125 μg/mL colistin, 50 μg/mL DJK-5 (equivalent to 2 × MIC of S. aureus and ½ × MIC of P. aeruginosa), or a combination of colistin/DJK-5 at both the low and high concentrations of colistin and re-incubated for an additional 24 h. Biofilms were washed three times in PBS and sonicated (Bandelin BactoSonic) at 100% intensity (40 kHz) for 5 min, serially diluted and plated for CFU. Monomicrobial biofilms were plated onto LB agar and co-biofilms were plated onto selective media – LB agar containing 7.5% NaCl and Pseudomonas Cetrimide Agar (PCA; Oxoid). Colonies were counted the following day to enumerate CFU/mL. Biofilm CFU was also performed in the presence of 0.1 mM H2O2 added to DFG before treatment with colistin and DJK-5, 10 μg/mL of 2-heptyl-4-hydroxyquinoline-N-oxide (HQNO), and the presence of co-biofilm supernatant concentrated using 10 kDa filter (Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter unit) centrifuged at 6000 g for 30 min. Biofilm CFUs were also performed with daptomycin; biofilms were treated the same as colistin combinations mentioned above with the same concentrations of DJK-5, with 10 μg/mL (10 × MIC S. aureus USA300 LAC).

Biofilm growth conditions and preparation for scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

P. aeruginosa and S. aureus monomicrobial and co-biofilms were grown for three days on calcium deficient hydroxyapatite (HA) (0.5’ diameter x 0.04-0.15’ thick; Clarkson Chromatography) discs submerged in DFG. Bacteria were prepared in PBS at 2 × 107 P. aeruginosa and 2.5 × 107 S. aureus to form monomicrobial biofilms and mixed 1:1 to form co-biofilms, a ratio determined to yield equal proportions of both bacteria after 72 h (Supplementary Fig. 14). The medium was changed daily over the course of three days. Subsequently, HA discs with bacteria were submerged for 3 h into DFG with either colistin, DJK-5 or a combination of colistin/DJK-5. P. aeruginosa monomicrobial biofilms were treated with 6.3 μg/mL colistin, 40 μg/mL DJK-5 and a combination of both at the same concentration. S. aureus monomicrobial biofilms were treated with 125 μg/mL colistin, 40 μg/mL DJK-5 and a combination of both at the same concentration. Co-biofilms were treated with either 6.3 μg/mL or 125 μg/mL colistin alone and in combination with 40 μg/mL DJK-5.

For SEM experiments, biofilms grown on HA discs were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in a 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) at 4 °C overnight. The next day, discs were washed three times with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer, transferred to 2% osmium tetroxide for 60 minutes, and subsequently washed again with 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer. The samples were dehydrated through an ethanol series (20, 50, 70, 90, 95, 100%) then critical point dried using ethanol as the intermediary and liquid carbon dioxide as the CDP fluid (Bal-Tec CPD-030 critical point dryer, Balzers, Liechtenstein). The samples were then coated with approximately 25 nm AuPd (80:20) and viewed in a JEOL 6700 F FE-SEM (JEOL Ltd, Tokyo, Japan) at an accelerating voltage of 5 kV.

Generation of a lacZ producing S. aureus USA300 LAC

A lacZ producing S. aureus USA LAC strain was constructed using a modified plasmid pJB18550 containing the sarA P1 promotor upstream of the S. aureus codon optimized lacZ50. The sarA P1 promotor was cloned from plasmid pKK2287 using primers shown in Supplementary Table 2 with a 5ʹ EcoRI site and a 3ʹ SalI site yielding plasmid pJB185sarAP1, a highly active and stable LacZ producing plasmid. pJB185sarAP1 was transformed via electroporation into the cloning intermediate strain S. aureus RN4220 (BEI resources, NR-45946), prior to cloning into S. aureus USA300 LAC. Electrocompetent S. aureus were generated based on the protocol outlined by Monk et al.88. Briefly, overnight S. aureus cultures were grown in Brain Heart Infusion broth (BHI, BD Difco) shaking at 37 °C, 250 rpm. Cultures were then diluted to an OD600 of 0.5 in fresh media and incubated for a further 90 min. Cells were then harvest at 4000 g for 10 min at 4 °C, supernatant was discarded, and cells were washed with an equal volume of ice-cold sterile distilled water, this was repeated two times. Then cells were resuspended in ice-cold sterile 10% (v/v) glycerol and 500 mM sucrose to 1/200th of the original culture volume. Cells were electroporated (Eppendorf eporator®) fresh using 1-5 µg of plasmid in 1 mm electroporation cuvettes (Bio-Rad) pulsed at 2.1 kV, 100 ohms, and 25 µF. Cells were immediately resuspended in 1 mL of pre-warmed BHI containing 500 mM sucrose and incubated at 37 °C for 1 hour prior to being plated on BHI agar plates containing 10 µg/mL of Chloramphenicol (Sigma), and 50 µg/mL of X-Gal (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-beta-D-galacto-pyranoside, Abcam) for 24 h. Blue colonies confirmed the presence of a functional plasmid, and were further confirmed using a restriction digest of the plasmid using EcoRV (Thermo Fisher, present within the sarA P1 insert) and PstI (Thermo Fisher).

Membrane leakage assay

P. aeruginosa and S. aureus monomicrobial and co-biofilms were grown as described above, with S. aureus USA300 LAC containing pJB185sarAP1. After 72 h, biofilms were washed with 1 × PBS three times and fresh pre-warmed media was added containing 125 μg/mL colistin, 50 μg/mL DJK-5, or a combination of colistin/DJK-5 for 1 h. After 1 h, the biofilm supernatant was harvested, filtered using 0.22 µm filters to remove intact planktonic cells, and 1 mL of supernatant was concentrated using 3 kDa filter (Amicon Ultra-0.5 3000 MWCO). One hundred µL was assayed for LacZ activity using 2-Nitrophenyl β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) following Krute el al.49. The yellow colorimetric shift was measured at a wavelength of 420 nm in 96-well plates (BMG CLARIOstar plus). LacZ activity was calculated via Miller units89. ({Miller; units}=1000times frac{{{OD}}_{420}}{{time}left(min right)times {volume}left({mL}right)times {{OD}}_{600}}) Modified Miller units could not be calculated due to the presence of FBS within the DFG media.

Murine skin abscess model

The cutaneous abscess model was performed as described previously for monomicrobial infections51. Clinically relevant isolates previously shown to co-exist during in vivo infection P. aeruginosa LESB58 and S. aureus USA300 LAC were grown individually to an OD600 of 1.0 in dYT broth. Bacterial cells were washed twice in PBS (Gibco; pH 7.4) and resuspended to an OD600 of 2.0 for S. aureus (~2.5 × 107 CFU/mL) and 1.0 for P. aeruginosa (~2.5 × 107 CFU/mL). P. aeruginosa and S. aureus were mixed (1:1) immediately prior injecting 50 μL subcutaneously into the right side of the dorsum. Dextrose, colistin (2.5 mg/kg), DJK-5 (3 mg/kg), daptomycin (2.5 mg/kg) and a combination of colistin/DJK-5 and daptomycin/DJK-5 were injected directly into the infected area one-hour post infection. Progression of infection was monitored daily, and mice euthanized by CO2 and cervical dislocation on day three. Dermonecrosis was measured using a caliper, and abscesses (including accumulated pus) were excised and homogenised in sterile PBS using a Mini-Beadbeater (BioSpec Products, Bartlesville, OK) for bacterial enumeration. Serial dilutions were plated on selective agar plates Pseudomonas cetrimide agar (Oxoid) to select for P. aeruginosa and 7.5% NaCl LB agar to select for S. aureus and incubated for 16-24 hours at 37 °C. At least three independent experiments containing 2-4 mice each were performed.

Study approval and animals

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Canadian Council on Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines following approval by the University of British Columbia Animal Care Committee (A14-0253), and the University of Otago Animal Ethics Committee (AUP19-125). Mice used in this study were outbred CD-1 or Swiss Webster (SW) mice(female, 6-7 weeks, weighed ~25 g). Animals were purchased from Charles River Laboratories, Inc. (Wilmington, MA) (CD-1) or the University of Otago Biomedical Research Facility (SW). Animals were group housed in cohorts of five littermates.

Statistical analysis

In vitro and in vivo experiments were performed with a minimum of three biological replicates unless stated otherwise. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism v10.2.3. For monomicrobial biofilms, a One-way ANOVA Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s correction was used, and for polymicrobial co-biofilms a two-way ANOVA with post-hoc Dunnett’s multiple correction test was used. The predicted additive effect (PAE) was determined by the sum of CFU log reduction obtained for each single treatment and Mann-Whitney test performed to compare PAE to the CFU counts obtained by the drug combination; synergy: p ≤ 0.0590.

Responses