DKK1 as a chemoresistant protein modulates oxaliplatin responses in colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) arises from benign polyps, posing challenges due to rising incidence, high mortality, and drug resistance. Surgical resection is the mainstay treatment, yet for unresectable cases or surgery intolerance, drug or radiation therapies are used pre- or post-surgery to shrink tumors or as adjuvant treatments [1,2,3]. Oxaliplatin, a third-generation platinum (Pt)-based compound, induces DNA interstrand crosslinks, forming DNA-Pt adducts that disrupt DNA replication, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Despite its efficacy, prolonged or repeated use of oxaliplatin often results in drug resistance, adverse events, tumor relapse, and reduced survival in CRC patients [4,5,6]. Therefore, comprehending how CRC surpasses oxaliplatin treatments is crucial. This insight will aid in devising innovative therapeutic approaches to enhance the clinical care of patients with oxaliplatin-resistant (OR) CRC.

Proposed mechanisms for oxaliplatin resistance include alterations in DNA damage response, changes in cell death and survival pathways, and alters in protein expression [7,8,9,10,11]. Pro-survival pathways such as AKT activation have been implicated in preventing cancer cell death. Notably, increased AKT activity have been observed in OR cancer cells, including hepatoma HepG2 cells [12], colorectal cancer cells [13,14,15], and cholangiocarcinoma cells [16]. Inhibiting the PI3K/AKT pathway has shown efficacy in enhancing oxaliplatin sensitivity in OR HepG2 [12] and OR CRC HCT116 cells [14]. These studies collectively highlight the critical role of AKT in fostering oxaliplatin resistance in cancer cells.

Dickkopf1 (DKK1), initially identified as an embryonic head inducer, holds significant importance in embryo development [17, 18]. This secreted protein contains two cysteine-rich domains: CRD1 and CRD2. The CRD1 domain interacts with the leucine zipper (LZ) domain of cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 (CKAP4) [19]. The CRD2 domain is required for interaction with low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6 (LRP6), identified as the first DKK1 receptor [20]. Canonically, DKK1 acts as a tumor suppressor by inhibiting Wnt signaling [17]. It forms a complex with LRP6 or Kremen receptors, leading to β-catenin degradation and Wnt signaling suppression. However, mutations in Wnt signaling components are common in human cancers. Despite its canonical role, DKK1 is often upregulated in various human cancers. A meta-analysis demonstrated that increased DKK1 expression correlates with shorter progression-free survival, disease-free survival, and time to recurrence in various cancers, including digestive system cancers [21]. Elevated DKK1 levels in tumor tissues are associated with poor prognosis in rectal cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [22, 23]. Additionally, high serum DKK1 levels are detected in CRC patients with liver metastasis, correlating with poorer overall survival [24]. It shows that DKK1 promotes the invasive ability of cancer cells in both gain- and loss-of-function studies [25, 26]. Recent research highlights the involvement of the DKK1-CKAP4 signal axis in tumor progression via AKT activation [19, 27, 28]. While DKK1’s role in promoting tumor malignant transformation is established, its link to drug resistance development remains underexplored.

In our study, we found elevated DKK1 expression in OR CRC cells. DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling activation significantly influences oxaliplatin responses in CRC cell and xenograft tumor models. Knockdown of DKK1 or CKAP4 not only suppresses AKT signaling but also enhances oxaliplatin sensitivity in OR CRC cells. Exposure to DKK1-containing conditional medium stimulates AKT signaling, thus reducing oxaliplatin-induced apoptosis and CRC cell sensitivity to oxaliplatin. Our findings reveal the importance of DKK1’s cysteine-rich domain 1 (CRD1) and CKAP4’s leucine zipper (LZ) domain in their cell surface interaction. Moreover, the LZ protein effectively disrupts DKK1-CKAP4 interaction, rendering OR CRC cells susceptible to oxaliplatin both in vitro and in vivo xenograft tumors. We suggest that DKK1 promotes chemoresistance in CRC cells by activating AKT signaling. Consequently, targeting DKK1 emerges as a promising therapeutic strategy for CRC patients with oxaliplatin resistance.

Results

DKK1 is upregulated in oxaliplatin-resistant colorectal cancer

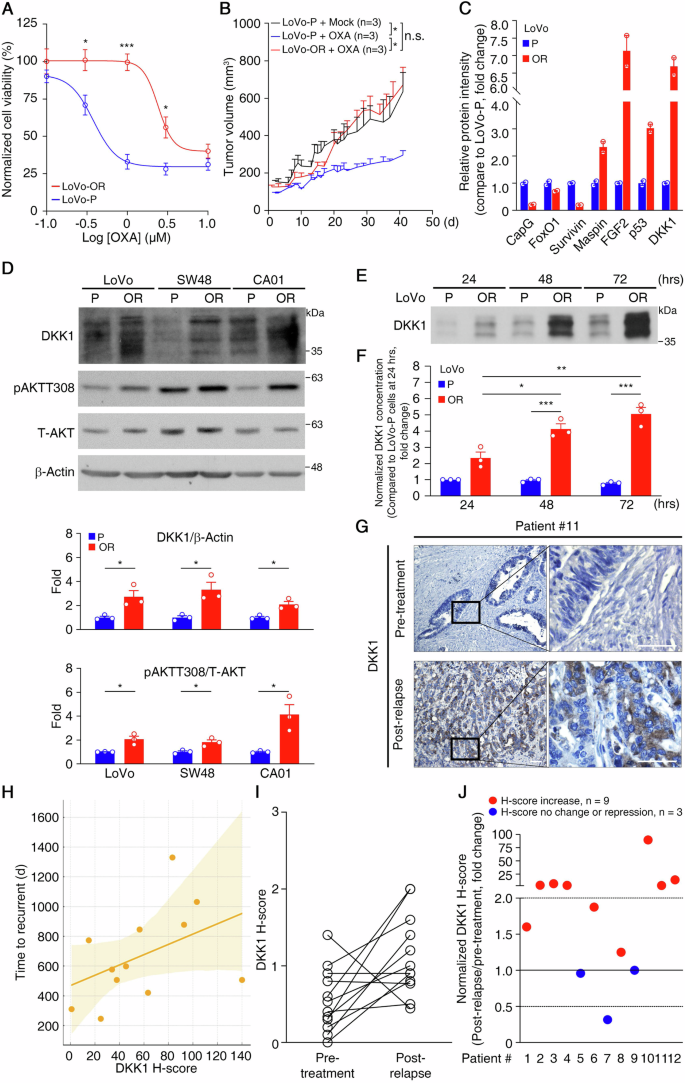

OR CRC cell lines (LoVo-OR, SW48-OR, and CA01-OR) were created following established protocols [7]. Utilizing MTS-based assays revealed reduced sensitivity to oxaliplatin compared to parental cells (P) (Fig. 1A and Supplementary Fig. 1A). Further analysis via tumor sphere formation (Supplementary Fig. 1B) and xenograft assays confirmed the robust growth of LoVo-OR cells in the presence of oxaliplatin (Fig. 1B and Supplementary Fig. 1C). To explore molecular factors influencing oxaliplatin responses, we conducted proteomic analysis comparing LoVo-OR and LoVo-P tumor spheres. Utilizing the Proteome Profiler Human XL Oncology Array, we identified three downregulated proteins (CapG, FOXO1, and Survivin) and four upregulated proteins (Maspin, p53, DKK1, and FGF2) in LoVo-OR spheres (Fig. 1C and Supplementary Fig. 1D). CapG, FOXO1, and Survivin are of significant interest due to their roles in tumor promotion and drug resistance; however, they were downregulated in LoVo-OR cells. Maspin and p53, both well-known tumor suppressors, were upregulated in LoVo-OR cells. Investigating their roles in OR cells could be significant, but the proteins DKK1 and FGF2 are even more noteworthy for this study. FGF2, a member of the fibroblast growth factor family, is known for its role in angiogenesis, wound healing, and embryonic development, as well as its involvement in tumorigenesis and cancer progression. DKK1, a member of the Dickkopf family, is a key modulator of the Wnt signaling pathway, which is crucial for cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. The upregulation of FGF2 and DKK1 in OR cells suggests that these proteins might play critical roles in the development of oxaliplatin resistance, making them prime targets for further investigation.

A Viability of LoVo-OR cells and their parental oxaliplatin-sensitive (P) counterparts after treatment with varying concentrations of oxaliplatin for 3 days. Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. (n = 3). B Growth curves of xenograft tumors derived from LoVo-P and LoVo-OR cells. Mice bearing LoVo-P tumors were treated with mock (n = 3), or administered 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week (n = 3). Mice bearing LoVo-OR tumors were treated with 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week (n = 3). Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, n.s. not significant. C The relative expression level of proteins between LoVo-P and LoVo-OR cells. Cell lysates from LoVo-P and LoVo-OR cells were prepared and analyzed by a proteome profiler human XL oncology array. Protein spots with different expression levels was quantified (n = 2). D Representative western blots of a panel of CRC cell lines (top) and quantification analysis (bottom). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). E Representative western blots of DKK1 in CM collected from LoVo-P and LoVo-OR at different time points. F Quantification of DKK1 in the CM collected from LoVo-P and LoVo-OR at different time points. Data are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. (n = 3). G Representative images of IHC analysis of DKK1 expression in patients with CRC. Magnified images of the boxed areas are shown. Scale bar: 50 μm. H Scatter plot showing the relationship between DKK1 H-score and time to recurrence in days. Each dot represents a patient. The regression line indicates a moderate positive correlation between higher DKK1 H-scores and longer times to recurrence. The shaded area represents the confidence interval. I The H-score for DKK1 in 12 matched pre-treatment and post-relapse CRC samples. p values were determined by paired two-tailed Student’s t test, *p < 0.05. J Fold change in the DKK1 H-score in 12 post-relapse versus pair-matched pre-treatment CRC samples.

Dysregulation of FGF signaling is associated with aggressive cancer traits, drug resistance, and poor clinical outcomes [29]. However, analysis from the UALCAN database showed that FGF2 upregulation wasn’t significantly linked to colon adenocarcinoma (COAD) tissues, tumor stages, lymph node status, or clinical outcomes (Supplementary Fig. 1E–H), and findings from the Human Protein Atlas indicate that FGF2 protein was not detected in CRC samples (https://www.proteinatlas.org/). On the contrary, DKK1 is frequently upregulated in various tumors and is associated with poor prognosis in patients [25, 30, 31]. Analysis of the UALCAN database showed a significant increase in DKK1 expression in COAD tissues (p = 0.0019) across different tumor stages and lymph node statuses (Supplementary Fig. 1I–K), suggesting its potential as a diagnostic marker for COAD patients. Although the association between DKK1 expression and overall survival (OS) in COAD patients was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 1L), analysis of the association between DKK1 and CRC recurrence-free survival (RFS) indicated that high DKK1 expression in stage III CRC patients was significantly associated with poorer RFS, as shown by the comprehensive Kaplan-Meier survival analysis platform (https://kmplot.com/analysis/). These findings suggest that CRC patients with high DKK1 expression tend to relapse earlier compared to those with low DKK1 expression after treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1M) and that DKK1 could be a marker of drug resistance development and a prognostic indicator of early relapse.

Western blotting analysis of CRC tumor spheres demonstrated upregulated DKK1 expression in OR cell lines (LoVo-OR, SW48-OR, and CA01-OR) compared to their oxaliplatin-sensitive counterparts (P) (Fig. 1D). As DKK1 is a secreted protein, we examined its levels in the cell culture media. Daily collection of medium samples showed detectable DKK1 protein in both LoVo-P and LoVo-OR cells, with higher levels in LoVo-OR cells (Fig. 1E). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) quantification normalized against cell numbers confirmed more efficient DKK1 secretion in LoVo-OR cells, with a concentration of secreted DKK1 (sDKK1) measured at 0.084 ± 0.023 ng/μl in LoVo-OR cell culture medium on day 3 (Fig. 1F). The levels of FGF2 protein were upregulated only in LoVo-OR cells compared to LoVo-P cells, and they were low in other cell lines and in the cultured medium (Supplementary Fig. 1N).

To associate the protein expression of DKK1 with the development of oxaliplatin resistance in CRC patients, we conducted IHC on 12 pairs of pre-treatment and post-relapse tumor samples (Fig. 1G and Supplementary Table). The pre-treatment samples were collected from patients who had not yet received oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, whereas the paired post-relapse samples were collected from the patients after they had undergone adjuvant oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy and subsequently experienced metastatic relapse. We grouped patients #1, #5, #7, #9, and #11 as having high DKK1 expression (DKK1 H-score >58), while the others were considered to have low DKK1 expression. Analysis showed that for patients with high DKK1 expression who received oxaliplatin treatment, there was no markedly increased expression of DKK1 in the post-relapse tumor samples, indicating a possible saturation point or inherent resistance mechanism. For patients with low DKK1 expression, there was a significant increase in DKK1 expression in most of the post-relapse tumor samples. This observation suggests that DKK1 signaling could be an adaptive response leading to oxaliplatin resistance. Moreover, a scatter plot with a regression line showed a moderate positive correlation between the DKK1 H-score and time to relapse. However, this correlation is not statistically significant, possibly due to the small sample size (Fig. 1H). Statistical analysis revealed a significant difference in DKK1 expression between pre-treatment and post-relapse CRC samples (p = 0.0197, Fig. 1I). Normalizing DKK1 H-scores from 12 post-relapse samples against their pre-treatment counterparts yielded fold changes in DKK1 expression. Remarkably, increased DKK1 H-scores (fold change >1.0) were found in 9 post-relapse CRCs, constituting 75% of the total 12 CRCs. Among these, 6 post-relapse CRCs (50% of the total 12 CRCs) exhibited over a 2-fold increase in DKK1 H-score (Fig. 1J). These results suggest a positive association between DKK1 expression and oxaliplatin resistance development in CRC. Additionally, the FGF2 protein was non-detectable in these pre-treatment and post-relapse tumor samples (Supplementary Fig. 1O)

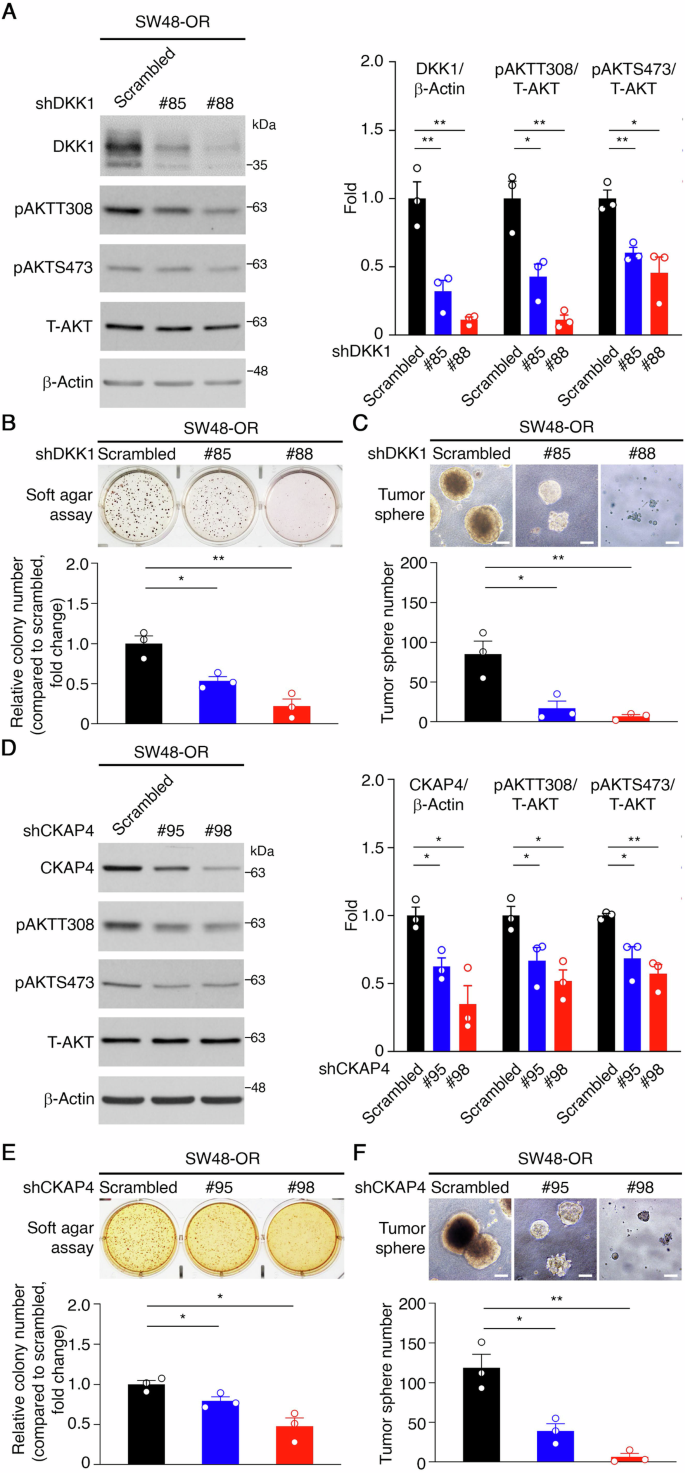

Downregulation of DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling sensitizes OR CRC cells to oxaliplatin

DKK1 is known to bind, cytoskeleton-associated protein 4 (CKAP4, a membrane protein), activating downstream AKT signaling and facilitating cancer cell proliferation and malignant transformation [17, 30]. To explore the involvement of DKK1 signaling in oxaliplatin resistance in CRC, we examined AKT activation, finding a positive correlation with increased DKK1 expression in OR CRC tumor spheres (Fig. 1D). Using RNA interference (RNAi), we reduced DKK1 expression with two independent DKK1-specific shRNAs (#85 and #88). SW48-OR cells expressing DKK1 shRNAs showed decreased DKK1 expression, leading to reduced phospho-AKT levels at Thr308 and Ser473 (Fig. 2A). DKK1 knockdown inhibited SW48-OR colony formation in soft-agar assays (Fig. 2B) and significantly reduced the number of SW48-OR tumor spheres in the presence of oxaliplatin (Fig. 2C). Similar results were observed in LoVo-OR and CA01-OR cells (Supplementary Fig. 2A–D), underscoring DKK1’s crucial role in activating AKT and modulating oxaliplatin responses in resistant CRC cells.

A Representative western blots of SW48-OR cells stably expressing either a scrambled shRNA or shRNAs specific for DKK1 (left) and quantification (right). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). B Representative images of soft agar colony formation assays for DKK1 knockdown experiments (top) and quantification of colony number (bottom). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). C Representative images of tumor sphere formation assays for DKK1 knockdown experiments (top) and quantification of tumor sphere number (bottom). ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). D Representative western blots of SW48-OR cells stably expressing either a scrambled shRNA or shRNAs specific for CKAP4 (left) and quantification (right). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). E Representative images of soft agar colony formation assays for CKAP4 knockdown experiments (top) and quantification of colony number (bottom). *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). F Representative images of tumor sphere formation assays for CKAP4 knockdown experiments (top) and quantification of tumor sphere number (bottom). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3).

Subsequently, UALCAN database analysis revealed elevated CKAP4 expression in COAD tissues (p = 0.0016), significant across tumor stages and lymph node status (Supplementary Fig. 2E–G). Although the association between CKAP4 mRNA expression and overall survival (OS) in COAD patients wasn’t statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 2H), we investigated CKAP4’s role in mediating DKK1-stimulated AKT signaling. SW48-OR cells expressing CKAP4 shRNAs exhibited decreased CKAP4 expression, reduced AKT activity, and impaired colony and tumor sphere formation compared to controls with scrambled shRNAs (Fig. 2D–F). Similar effects were seen in LoVo-OR and CA01-OR cells (Supplementary Fig. 2I–L). In conclusion, our findings suggest that DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling axis is upregulated in oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cells and plays a crucial role in promoting cell growth in the presence of oxaliplatin.

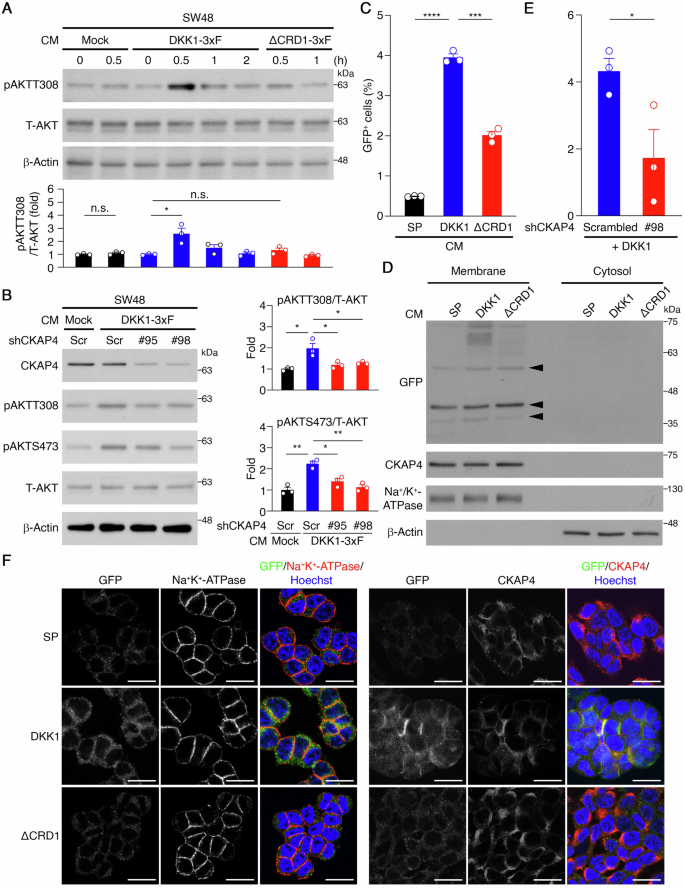

Secreted DKK1-mediated activation of AKT signaling via CKAP4 in colorectal cancer cells

The DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling axis’s impact on cancer biology has been previously demonstrated by manipulating cellular DKK1 expression levels [19, 30]. We aimed to address the function of secreted DKK1 (sDKK1) in CRC cells. sDKK1-containing conditioned media (CM) was obtained from 293 cells expressing 3xFlag-tagged DKK1 (DKK1-3xF, Supplementary Fig. 3A) after a 3-day serum-free medium incubation. Levels of DKK1-3xF in CM were assessed via western blotting (Supplementary Fig. 3B) and ELISA. Time-course CM treatment of SW48 cells revealed significant AKT activation at the 30-minute mark with DKK1-3xF, contrasting with negligible effects observed with mock CM (Fig. 3A). To assess sDKK1’s interaction with the CKAP4 receptor, we employed a truncated form of DKK1 lacking CRD1 (DKK1ΔCRD1-3xF; Supplementary Fig. 3A), responsible for CKAP4 interaction [32]. CM containing DKK1ΔCRD1-3xF (ΔCRD1-3xF) was collected and leveled (Supplementary Fig. 3B), revealing reduced DKK1-induced AKT phosphorylation in SW48 cells (Fig. 3A), similarly observed in CA01 cells (Supplementary Fig. 3C). Subsequently, we explored CKAP4’s role in mediating sDKK1-induced AKT signaling. SW48 cells expressing shRNAs against CKAP4 treated with DKK1-3xF-containing CM showed partially attenuated DKK1-3xF-induced phospho-AKT levels (Fig. 3B), suggesting CKAP4’s involvement in mediating sDKK1-activated AKT.

A Representative western blots of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells (top) and quantification analysis (bottom). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05. n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). B Representative western blots of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells expressing CKAP4 shRNAs or carrying a scrambled control (left) and quantification analysis (right). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). C Percentage of GFP+ cells in the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells. ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). D Representative western blots of membrane protein isolation and cell fractionation experiments of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells (n = 3). Arrows indicate non-specific bands. E Percentage of GFP+ cells in CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells expressing CKAP4 shRNAs or a scrambled control. *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). F Representative images of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells, as determined by immunocytochemistry and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Scale bar: 20 μm.

Additionally, to visualize sDKK1’s interaction with CKAP4 on the plasma membrane, we generated a DKK1-GFP fusion protein, where GFP was tagged at DKK1’s C-terminus. The signal peptide (SP) [33] derived from DKK1 was fused to the N-terminus of GFP (SP-GFP) for GFP secretion guidance, serving as a control (Supplementary Fig. 3A). CM collected from 293 cells expressing SP-GFP (SP), DKK1-GFP (DKK1), or DKK1ΔCRD1-GFP (ΔCRD1) was analyzed and leveled (Supplementary Fig. 3D). Flow cytometry analysis of SW48 cells incubated with CM revealed a significant decrease in GFP+ cells with ΔCRD1 CM compared to DKK1 CM (Fig. 3C and Supplementary Fig. 3E). Plasma membrane isolation assays confirmed DKK1 presence in the plasma membrane fraction, with reduced levels for ΔCRD1, supporting sDKK1’s binding to the cell plasma membrane, attenuated by CRD1 truncation (Fig. 3D). To validate CKAP4’s role in sDKK1-cell interactions, flow cytometry analysis of SW48 cells expressing shRNAs against CKAP4 incubated with DKK1 CM revealed reduced GFP+ cells (Fig. 3E and Supplementary Fig. 3F). Immunocytochemistry (ICC) analysis further confirmed sDKK1’s association with the plasma membrane and CKAP4, with colocalization observed and reduced by CRD1 truncation (Fig. 3F). These findings support CRD1’s critical role in sDKK1 interaction with CKAP4 on the cell surface to activate AKT signaling.

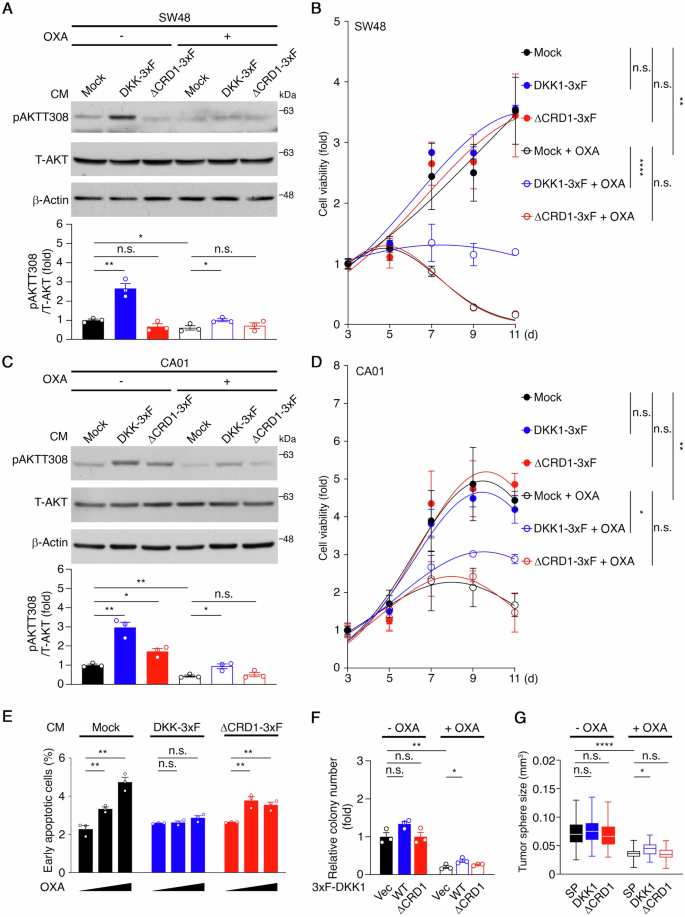

sDKK1 modulates oxaliplatin responses in CRC cells

Next, we investigated the impact of sDKK1 on oxaliplatin responses in CRC cells via the CKAP4/AKT pathway. CM containing sDKK1 was obtained from 293 cells expressing DKK1-3xF, DKK1ΔCRD1-3xF (ΔCRD1-3xF), or an empty vector (Mock). SW48 cells treated with 0.1 μM oxaliplatin for 24 hours, followed by a 30-minute CM incubation. Western blotting showed increased phospho-AKT levels with DKK1-3xF CM, partially restoring oxaliplatin-inhibited AKT phosphorylation, weakened by CRD1 truncation (Fig. 4A). MTS assays indicated no significant effect on cell proliferation, but DKK1-3xF CM partially rescued oxaliplatin-inhibited cell growth (Fig. 4B). Similar results were observed in CA01 cells (Fig. 4C, D). Apoptosis assays in SW48 cells showed DKK1-3xF CM minimized oxaliplatin-induced early apoptosis compared to mock or ΔCRD1-3xF CM (Fig. 4E and Supplementary Fig. 4A). Long-term focus formation assays in SW48 cells stably expressing DKK1-3xF and ΔCRD1-3xF indicated DKK1 expression partially rescued cells from oxaliplatin treatment (Fig. 4F and Supplementary Fig. 4B). Anchorage-independent cell growth assays in SW48 cells demonstrated DKK1 expression partially restored oxaliplatin-suppressed sphere growth, whereas ΔCRD1 did not (Fig. 4G and Supplementary Fig. 4C). These findings collectively suggest sDKK1 contributes to modulating oxaliplatin responses through the CKAP4/AKT pathway.

A Representative western blots of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells in response to oxaliplatin (top) and quantification analysis (bottom). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). B Cell growth curves of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 in response to oxaliplatin, as determined by MTS assays. **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). C Representative western blots of the CM treatment experiments on CA01 cells in response to oxaliplatin (top) and quantification analysis (bottom). β-Actin served as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). D Cell growth curves of the CM treatment experiments on CA01 in response to oxaliplatin, as determined by MTS assays. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). E Apoptosis analysis was performed in CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells in response to 0, 0.1, and 0.3 µM of oxaliplatin. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). F Quantification analysis of clonogenic growth assays for SW48 cells stably expressing DKK1-3xF (WT) and DKK1ΔCRD1-3xF (ΔCRD1), or carrying an empty vector (Vec) in response to oxaliplatin (top) and (bottom). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). G Quantification analysis of tumor sphere size in SW48 cells stably expressing SP-GFP (SP), DKK1-GFP (DKK1), or DKK1ΔCRD1-GFP (ΔCRD1) in response to oxaliplatin. *p < 0.05, ****p < 0.0001, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM. A total of 30 tumor spheres were counted in each experimental setting.

DKK1 sustains CRC tumor growth in the presence of oxaliplatin

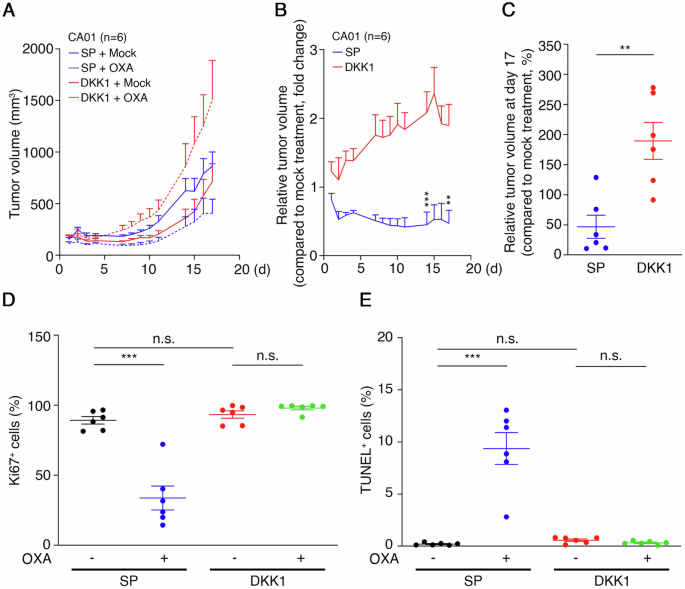

In a study on CRC’s oxaliplatin resistance, CA01 cells expressing SP-GFP (SP) or DKK1-GFP (DKK1) were xenografted into mice. Mice received mock or oxaliplatin injections (5 mg/kg) weekly for 3 weeks. DKK1-GFP expression had no significant effect on tumor volume. However, oxaliplatin notably reduced tumor volume in SP-GFP tumors, whereas DKK1-GFP tumors-maintained growth (Fig. 5A, B). By treatment end, SP-GFP tumors decreased while DKK1-GFP tumors increased in size (Fig. 5C). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis revealed a decrease in Ki67+ cells to 33.7 ± 8.5% and an increase in TUNEL+ cells to 9.4 ± 1.5% in SP-GFP tumors, whereas these responses were attenuated in DKK1-GFP tumors (Fig. 5D, E and Supplementary Fig. 5A, B). To confirm DKK1-GFP secretion in tumor-bearing mice, blood plasma underwent immunoprecipitation with anti-GFP antibodies and protein A/G beads. Western blotting confirmed GFP fusion protein presence, indicating SP-GFP and DKK1-GFP secretion from tumors into the blood (Supplementary Fig. 5C).

A Growth curves of xenograft tumors derived from CA01 cells stably expressing SP-GFP or DKK1-GFP. The tumor-bearing mice were treated with mock (n = 6) or administered 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week (n = 6) for 3 weeks. Data are mean ± SEM. B Curves of relative tumor volume in xenograft tumors from (A). Relative tumor volume was calculated using oxaliplatin-treated tumor volume/mock-treated tumor volume. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM. C Relative tumor volume at day 17, as described in (B), was calculated as oxaliplatin-treated volume/mock-treated volume × 100%. **p < 0.01. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6). D The percentage of Ki67+ cells in CA01 xenograft tumors are shown in (A). A total of 2000 cells were calculated in each tumor section. ***p < 0.001, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6). E The percentage of TUNEL+ cells in CA01 xenograft tumors is shown in (A). A total of 2000 cells were calculated in each tumor section. ***p < 0.001, n.s. not significant. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6).

Findings from SW48 cells expressing DKK1-3xF (WT), DKK1ΔCRD1-3xF (ΔCRD1), or empty vector (Vec) mirrored those in CA01 xenograft tumors. DKK1 or ΔCRD1 expression didn’t significantly enhance SW48 xenograft growth. Oxaliplatin notably reduced tumor volume in ΔCRD1 or Vec tumors, while DKK1-expressing tumors remained stable (Supplementary Fig. 5D, E). By treatment end, ΔCRD1 and Vec tumors decreased in size, while DKK1 tumors increased (Supplementary Fig. 5F). Animal body weights remained consistent throughout treatment (Supplementary Fig. 5G). These findings support elevated DKK1 sustaining CRC tumor growth in oxaliplatin presence, indicating its key role in oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer.

LZ protein suppresses oxaliplatin-resistant CRC cell growth

Our findings suggest that the crucial role of the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction in regulating oxaliplatin responses in CRC cell lines, indicating a potential therapeutic strategy for suppressing OR CRC cell growth. Given the reported requirement for the LZ domain in CKAP4 and the CRD1 in DKK1 for their interaction [19, 32], we investigated the disruptive potential of an LZ domain-containing protein.

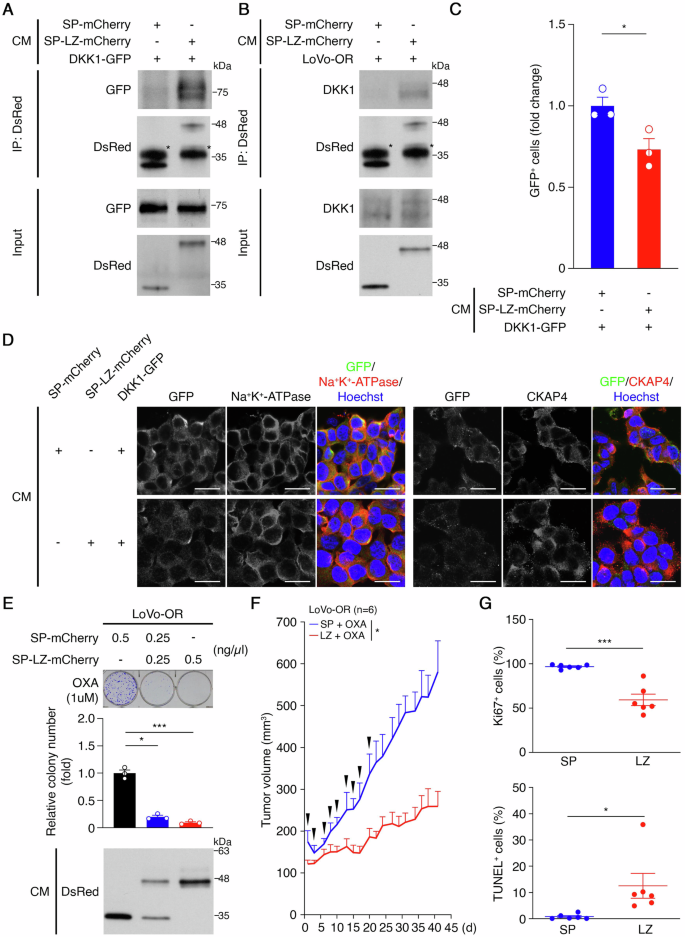

We cloned a one-hundred-amino-acid region overlapping the defined LZ domain (aa 468–503) of CKAP4 [30], generating a secreted form of the SP-LZ-mCherry fusion protein (LZ protein) (Supplementary Fig. 6A). CM containing LZ protein or SP-mCherry was collected, confirmed, and normalized for consistency (Supplementary Fig. 6B). To assess the interaction of the LZ protein with sDKK1 via CRD1, immunoprecipitation assays were performed using anti-DsRed antibodies with CMs containing DKK1-GFP and LZ protein. The results revealed GFP fusion proteins in the anti-DsRed immunoprecipitation complex in DKK1-GFP CM, with diminished levels in DKK1ΔCRD1-GFP CM (Supplementary Fig. 6C), suggesting that the CRD1 mainly facilitates the interaction between the LZ protein and sDKK1. Further validation of the specificity of the LZ protein/sDKK1 interaction was achieved, demonstrating the specific interaction of the LZ protein with both exogenously expressed DKK1-GFP and endogenous sDKK1 proteins (Fig. 6A, B). To assess the impact of the LZ protein on the binding of sDKK1 to CKAP4 on the cell surface, flow cytometry and ICC analyses were performed using SW48 cells incubated with DKK1-GFP + SP-mCherry CM or DKK1-GFP + LZ protein CM for 30 minutes. The percentage of GFP+ cells (Fig. 6C and Supplementary Fig. 6D) and the association of sDKK1-GFP with the cell surface (Fig. 6D) were reduced by the presence of LZ protein CM, contrasting with SP-mCherry. These results suggest that the LZ protein functions by sequestering sDKK1, thereby interfering with the binding of sDKK1 to CKAP4 on the cell surface.

A Representative western blots of DKK1-GFP coimmunoprecipitated with anti-DsRed antibodies. (n = 3). B Representative western blots of endogenous DKK1 coimmunoprecipitated with anti-DsRed antibodies. (n = 3). C Percentage of GFP+ cells in CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells. *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM. (n = 3). D Representative images of the CM treatment experiments on SW48 cells, as determined by immunocytochemistry and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Scale bar: 20 μm. E Representative images of clonogenic growth assays for CM treatment experiments on LoVo-OR cells (top), quantification analysis of colony number (middle), and representative western blots of mCherry fusion proteins in CM (bottom). *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 3). F Tumor growth curves in mice bearing xenograft tumors originating from LoVo-OR cells treated with 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week (n = 12). When the tumor size reached 100 mm3, the tumor-bearing mice were grouped into SP (n = 6) and LZ (n = 6). The SP group had SP-mCherry containing CM, and the LZ group had SP-LZ-mCherry containing CM three times per week for 3 weeks. After CM withdrawal, tumor growth was monitored for an additional 3 weeks. Oxaliplatin was administered throughout the courses. Arrows indicate CM administration. *p < 0.05. Data are mean ± SEM. G The percentage of Ki67+ cells (top) and TUNEL+ cells (bottom) in LoVo-OR xenograft tumors, as described in (F). A total of 2000 cells were counted in each tumor section. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM (n = 6).

We then evaluated the LZ protein’s therapeutic potential in inhibiting OR CRC growth. Long-term focus formation assays demonstrated significantly inhibited colony formation in LoVo-OR cells when exposed to LZ protein CM compared to SP-mCherry (Fig. 6E). To validate these findings, LoVo-OR cells were xenografted into mice, divided into SP and LZ groups, and administrated SP-mCherry CM and LZ protein CM three times per week for 3 weeks. After CM withdrawal, tumor growth was monitored for an additional 3 weeks with continuous oxaliplatin administration (Supplementary Fig. 6E). Notably, LoVo-OR tumor growth was significantly suppressed in the LZ group compared to the SP group, and this effect persisted for up to 3 weeks after discontinuing LZ protein CM administration (Fig. 6F and Supplementary Fig. 6F). Importantly, there were no discernible effects on the mice’s body weight (Supplementary Fig. 6G) and did not cause histopathological damage to organs, including the lung, kidney, or liver (Supplementary Fig. 6H), suggesting the safety of CM administration. Additionally, IHC analysis of tumor samples revealed a reduced percentage of actively proliferating tumor cells (96.9 ± 0.9% in SP, and 59.4 ± 6.5% in LZ) and an increased percentage of apoptotic cells (0.8 ± 0.4 in SP, and 12.5 ± 4.8% in LZ) in the LZ group (Fig. 6G and Supplementary Fig. 6I, J). These findings collectively support the LZ protein’s inhibitory effect on oxaliplatin-resistant CRC growth, suggesting a promising therapeutic strategy for CRC characterized by elevated DKK1 levels.

Discussion

Our study reveals a clear link between DKK1 expression and oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer. DKK1 secretion is notably higher in OR CRC cells compared to parental cells. Clinically, DKK1 expression is significantly elevated in post-relapse tumors from patients on oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy, suggesting its role in resistance development in CRC. Mechanistically, we demonstrated that secreted DKK1 (sDKK1) activates AKT by binding CKAP4 on the cell membrane. This DKK1 signaling shields CRC cells from oxaliplatin-induced cytotoxicity, causing oxaliplatin resistance in vitro and in vivo. Importantly, blocking the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction with the LZ protein heightened OR CRC cells’ sensitivity to oxaliplatin and inhibited OR CRC xenograft tumor growth. In summary, our findings highlight two main points: 1) DKK1 signaling is pivotal in regulating oxaliplatin responses in CRC, and 2) inhibiting the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction using the LZ domain could be a promising therapy for oxaliplatin-resistant CRC.

The development of oxaliplatin resistance is a multifaceted process involving a variety of proteins that vary according to the biological samples and conditions used. Thus, it is difficult to comprehensively understand oxaliplatin resistance development using only a few analytical methods. In this study, we performed protein array analysis to screen candidates that may contribute to the development of oxaliplatin resistance. Although the detection capabilities were limited by the antibodies spotted on the array, we identified seven proteins with significant expression differences in oxaliplatin-resistant (OR) cells. In this shortlist, CapG has been documented to be upregulated in many types of cancer cells and is associated with patient prognosis. It plays a role in promoting the proliferation, migration, invasion, and metastasis of numerous tumor cells [34,35,36,37]. Additionally, it was is now considered a novel biomarker for early gastric cancer and is involved in Wnt signaling pathways [38] and promotes the development of paclitaxel resistance in breast cancer [39]. FOXO1, a member of the forkhead (FOXO) box family of transcription factors, contains a highly conserved DNA-binding domain. FOXO1 and FOXO3 as critical modulators in cellular processes, including drug-induced resistance in different types of cancer cells [40, 41]. Moreover, FOXO1 acts as a tumor suppressor while also maintaining cancer stem cells in some digestive system cancers, including liver, colorectal, and gastric cancers [42]. Survivin is predominantly expressed in human cancers, compared to normal tissues. It is one of the most tumor-specific molecules identified, known to antagonize apoptosis, support tumor-associated angiogenesis, and act as a resistance factor to various anticancer therapies [43]. These three proteins are of significant interest due to their tumor-promoting and drug resistance developing roles. The roles of downregulation of these three proteins in CRC drug resistance require further studies. Maspin [44] and p53, are both well-known tumor suppressors. Investigating their roles in regulating the development of oxaliplatin resistance could be significant; however, their upregulated expression in oxaliplatin-resistant cells may counteract the malignant characteristics typically associated with these resistant cells.

AKT activation is intricately regulated by diverse upstream pathways, notably phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), which regulates fundamental cellular processes like apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation. This pathway, notorious for driving malignant transformation, is implicated in key cancer features. Moreover, AKT activation is strongly linked to drug resistance in various cancers [45, 46], including cisplatin-resistant lung cancer [47], acquired resistance to standard therapies breast cancer [48], and BRAF inhibitor-resistant melanoma [49]. Our study revealed that sDKK1’s role in stimulating AKT activation in oxaliplatin resistance. Exploring DKK1 signaling in other AKT-driven drug-resistant cancers and assessing the LZ protein’s effects could be promising future research directions.

Clinical studies link higher DKK1 levels with shorter recurrence times and poorer prognosis in patients [21,22,23]. Elevated DKK1 is seen in CRC patients with liver metastasis, correlating with reduced overall survival [24]. Both gain- and loss-of-function studies show DKK1’s role in tumor progression and malignant transformation through the DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling [19, 27, 28]. In our study, we demonstrated a positive association between the protein expression of DKK1 and the development of oxaliplatin resistance in CRC. Through the DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling axis, upregulated DKK1 plays a crucial role in integrating diverse cellular events in different CRC cell lines in response to oxaliplatin, including cell proliferation, colony formation, anchorage-independent cell growth, apoptosis, and xenograft tumor growth.

It’s proposed that DKK1’s CRD1 and CKAP4’s LZ domain are crucial for their interaction, supported by immunoprecipitation-western blot (IP-WB) assays using cell lysates from cells expressing variants of DKK1 or CKAP4 [19]. To explore their cell surface interaction, we utilized GFP-tagged DKK1 in conditioned medium to visualize sDKK1 binding to the cell membrane. Our findings highlight the essential role of CRD1 in sDKK1’s association with CKAP4 on the cell surface, as evidenced by reduced AKT activity, membrane association, and modulation of oxaliplatin responses upon incubation with CRD1-truncated DKK1. This underscores the therapeutic potential of targeting the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction in OR CRCs.

Blocking the interaction between DKK1 and CKAP4 using designed antibodies is being explored as a potential therapeutic strategy for several human cancers. Elevated levels of DKK1 are associated with focal bone lesions in multiple myeloma (MM) [50]. Preclinical studies in mice with human MM showed that the humanized DKK1-neutralizing antibody BHQ880 reduced MM cell numbers [51]. A phase IB study found that combining BHQ880 with zoledronic acid was tolerated and showed potential clinical activity in MM patients [52]. Another humanized DKK1-neutralizing antibody, DKN-01, demonstrated tolerability and clinical activity in phase I studies with advanced biliary cancer, non-small cell lung cancer, esophageal cancer, and gastroesophageal junction tumors [53,54,55]. In a phase II study, DKN-01 combined with tislelizumab and chemotherapy improved overall survival in advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma patients [56]. Furthermore, anti-CKAP4 monoclonal antibodies effectively blocked the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction, reducing AKT activation, pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, and tumor growth in mouse models [57]. Overall, these findings suggest that inhibiting DKK1 signaling holds promise as a cancer therapeutic strategy.

In our strategy, rather than creating DKK1-neutralizing antibodies, we designed an SP-LZ-mCherry fusion protein, utilizing the signal peptide (SP) to guide LZ-mCherry secretion. These secreted LZ proteins interact efficiently with DKK1, disrupting the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction on the cell membrane. This approach effectively inhibits colony formation and xenograft tumor growth in OR CRC cells, highlighting the LZ protein’s therapeutic promise for OR CRC. Future research will assess the LZ protein’s anti-tumor efficacy in DKK1-overexpressing cancers. Notably, DKK1’s association with a suppressive tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) and its potential as an immunotherapeutic target are significant [58, 59]. Therefore, investigating the LZ protein’s impact on DKK1-mediated TIME modulation is crucial. Our study presents a novel approach to dampen DKK1 signaling via the LZ protein, offering a convenient method for generating LZ fusion proteins through SP-directed protein secretion.

Our study not only unveiled a positive association between the expression of DKK1 and the development of oxaliplatin resistance in colorectal cancer (CRC) but also elucidated the molecular mechanism through which the DKK1/CKAP4 interaction modulates oxaliplatin responses. Furthermore, our results strongly indicate that attenuating the DKK1/CKAP4/AKT signaling axis using the LZ protein effectively suppressed oxaliplatin-resistant (OR) CRC cell growth both in vitro and in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 6K). This finding holds promise as a potential therapeutic strategy for the treatment of OR CRC.

Materials and methods

Patient samples and establishment of a colorectal cancer cell line

Patients provided signed informed consent prior to their inclusion in this study, which was approved by the institutional review board at the National Cheng Kung University Hospital (B-BR-106-068, NCKUH, Tainan, Taiwan). Patients were diagnosed with early-stage CRC and received surgery and oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy after tumor resection. All of them developed oxaliplatin resistance, and the tumors recurred in different parts of the body. They underwent surgery again and provided post-relapse tumor samples (Supplementary Table).

No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. No samples were excluded. The formalin-fixed tissue was analyzed to confirm the presence of viable tumor by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining.

To generate a primary CRC cell line, CA01, the procedures were performed as previously described [60]. Briefly, a tumor section was excised from a 63-year-old Taiwanese woman who underwent surgical operations at NCKU in 2020 (0140140-2). The sample was mechanically fragmented and enzymatically digested. Cells were collected and cultured in DMEM/F-12 medium (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Hyclone, Logan, UT, USA) and 100 U/ml of penicillin–streptomycin (Gibco) for further experiments.

In vivo xenograft tumor growth studies

Mice were maintained in accordance with facility guidelines on animal welfare and with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Usage Committee (IACUC) of the National Cheng Kung University. Four- to 6-week-old female NOD/SCID mice (NCKU, Tainan, Taiwan) were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment in the animal facility of NCKU. For oxaliplatin sensitivity assays, 1 × 107 LoVo-P or LoVo-OR cells were mixed with Matrigel (1:1, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and subcutaneously inoculated into the flanks of the mice. LoVo-OR tumor-bearing mice (n = 3) were administered oxaliplatin (5 mg/kg) once per week for 6 weeks by intraperitoneal injection. The LoVo-P tumor-bearing mice were grouped into mock (n = 3) and OXA (n = 3) groups when tumor size reached 100 mm3. The mock group was administered PBS, and the OXA group was given 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week for 6 weeks by intraperitoneal injection.

To evaluate the effects of DKK1 on oxaliplatin sensitivity, 2 × 106 CA01 cells stably expressing SP-GFP or DKK1-GFP were grown as xenograft tumors. When tumor size reached 100 mm3, mice were randomly assigned to two groups: mock (n = 6) and OXA (n = 6). The mock group was administered PBS, and the OXA group was administered 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week for 3 weeks by intraperitoneal injection. In addition, 2 ×106 SW48 cells stably expressing DKK1-3xF, DKK1ΔCRD1-3xF, or carrying an empty vector were grown as xenograft tumors. The tumor-bearing mice were randomly assigned to two groups: mock (n = 6) and OXA (n = 6). The mock group was administered PBS, and the OXA group was administered 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week for 3 weeks by intraperitoneal injection.

To address the impact of the LZ protein on suppressing oxaliplatin-resistant tumor growth, 1 × 107 LoVo-OR cells were subcutaneously inoculated into the flanks of the mice. The mice were administered 5 mg/kg oxaliplatin once per week. When the tumor size reached 100 mm3, the tumor-bearing mice were randomly assigned to two groups: SP (n = 6) and LZ (n = 6). The SP group was intraperitoneally injected with SP-mCherry containing CM and the LZ group was administered SP-LZ-mCherry containing CM three times per week for 3 weeks. After CM withdrawal, the tumor growth was monitored for an additional 3 weeks. Oxaliplatin was administered throughout the courses.

The tumor-bearing mice were randomly grouped using Research Randomizer at http://www.randomizer.org. The sample size was not statistically determined. Tumors and body weight were monitored daily. Tumor size was calculated using the following formula: volume = [length × (width)²]/2. The relative tumor volume was determined by dividing the volume of oxaliplatin-treated tumors by that of mock-treated tumors. When the tumor size reached 1000 mm³, the mice were humanely euthanized. The investigators were not blinded to group allocation or outcome assessment, and no animals were excluded from the experiments.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, New York City, NY, USA). The in vitro experiments were performed in biological triplicate each time and independently repeated at least 3 times. Data are presented as the mean ± SEM and the number (n) of samples used was as indicated. An unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test was used to compare differences between the control and experimental groups, unless otherwise indicated. For all statistical analyses, differences were labeled as *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****; n.s. = not significant. p values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Responses