Does earning money empower women? Evidence from India

Introduction

Empowerment of women has become a focal point in global discussions on equity and development (Kabeer, 2005; Malhotra & Schuler, 2005). Financial independence is often touted as a key factor in enhancing women’s status in society, yet emerging evidence suggests a complex and sometimes paradoxical relationship between earning money and women’s empowerment, particularly in South Asian contexts (Kabeer, 2021; Gupta & Roy, 2023). While earning money can expand women’s autonomy in certain domains, it may simultaneously create new vulnerabilities or exacerbate existing ones within intimate relationships (Schuler et al., 2017; Ali & Kiani, 2021).

This paradox is particularly evident in India, where women’s increased economic participation has produced mixed outcomes. Recent studies indicate that while financial independence can enhance women’s agency and decision-making power in public spheres, it may trigger adverse reactions within households, leading to increased intimate partner violence or restricted marital rights (Swain & Wallentin, 2016; Kabeer, 2020; Gupta & Roy, 2023). The complexity is further heightened by the intersection of gender with other social categories such as caste, religion, and region, revealing intricate patterns of disadvantage that women face in India (Varghese, 2020).

Several critical gaps persist in our understanding of this complex relationship. First, there is limited comprehension of how earning money differentially impacts women’s empowerment across various life domains—from public spaces where financial autonomy might enhance status, to private spaces where it might threaten traditional power dynamics. This gap is especially evident in understanding the nuanced effects of financial independence on decision-making authority, self-perception, societal respect, and the balance of power in gendered relations within households.

Second, existing research has predominantly focused on measuring empowerment through a limited set of parameters: participation in household decision-making, freedom of movement, control over resources, and women’s attitudes towards domestic violence (Alam et al., 2021). However, these measurements often overlook crucial aspects, such as the actual incidence of emotional, physical, and sexual violence against women. Those who have studied incidences of violence have mostly compared it to attitudes towards violence (West, 2006; Jejeebhoy et al., 2017; Dasgupta, 2019; Fattah & Camellia, 2020), while those who have connected it to earning money have done so in isolation from other measures of empowerment (Hidrobo & Fernald, 2013; Paul, 2016; Schuler et al., 2017; Assunção & Tavares, 2020).

This study addresses these gaps by exploring the paradoxical relationship between earning money and women’s empowerment in India, examining how financial independence simultaneously enables and constrains women’s autonomy across different life domains. Specifically, the research seeks to answer critical questions: How does earning money differentially impact women’s decision-making power in household matters versus decisions related to intimate relationships? To what extent does financial independence enhance women’s autonomy in public spaces while potentially constraining their rights within intimate relationships? How does earning money influence the incidence of intimate partner violence, and does this differ from its impact on attitudes toward such violence? To what extent are women able to exercise their marital rights? And, overall, does earning money truly empower women, or does it create new forms of vulnerability while addressing others?

Utilizing Bayesian statistical analyses, this study examines data from the Indian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) 2019–21. The DHS surveys women aged 15 to 49 and men aged 15 to 64, but it asks questions about marital rights and intimate partner relationships only to those who are currently married or in a relationship with a partner. Given that none of the women in the dataset identify as living with a partner, this analysis is primarily applicable to married women in the Indian context.

This study makes several unique contributions to the existing literature. First, it examines the contribution of women to family earnings as the predictor variable and the state of empowerment as the outcome variable, moving beyond the traditional focus on mere employment status and addressing a notable gap in Indian empowerment research (Yount et al., 2019). Second, it broadens the scope of empowerment indicators by including both process and outcome measures, particularly incorporating actual incidents of violence alongside attitudes toward violence. Third, the study compares outcomes across family wealth differentials, providing a more nuanced understanding of how economic factors interact with empowerment. Fourth, by utilizing extensive secondary data from the Indian DHS, it offers insights based on a larger sample size compared to the smaller, primary data samples used in most existing studies. Lastly, the study proposes a novel theoretical approach towards examining women’s empowerment, viewing it as the expansion of psychological real estate within the psycho-spatial dimensions of marriage and family.

Literature review

Conceptual framework of women’s empowerment

Following Kabeer (1994), most of the literature on empowerment relies heavily on the concept of choice and agency. At the elementary level, women empowerment is seen as the pursuit of equality between men and women (Eisenstein, 1979; Jaggar, 1983; Moser, 1989, 1993; Mellor, 1997; Tong, 2019). Perceived as such, empowerment is a process of awareness and transformation, where women gain the ability to make choices and act on them to bring about change (Kabeer, 1999). However, empowerment is not a linear process, but rather a complex and dynamic one that involves negotiation, resistance, and struggle against social norms and institutions (Malhotra et al., 2002; Kabeer, 2000, 2005; Alsop et al., 2006).

Empowerment is also understood to be a state meaning having the ability to make decisions and act on them, despite the constraints created by existing power dynamics. It is power relations and the social, cultural, and political context in which they are exercised that shape women’s economic, social, and political empowerment (Batliwala, 1994, 2007; Narayan, 2000; Malhotra & Schuler, 2005).

Multidimensional nature of empowerment

Women’s experiences and identities are not homogenous. Therefore, empowerment is not a one-size-fits-all concept, but rather context-specific to needs and realities of different groups of women (Crenshaw, 1989; Fraser, 1989; Butler, 2006) and multidimensional, encompassing various aspects such as increasing access to and control over economic resources, enhancing social status and networks, increasing participation in decision-making processes at various levels, and enhancing self-confidence, self-esteem, and belief in the ability to effect change (Batliwala, 1994; McEwan, 2001; Kabeer, 2005; Alsop, Bertelsen, & Holland, 2006; Hankivsky, 2012; Collins, 2015).

Empowerment is seen as expanding real freedoms rather than just increasing income or welfare (Robeyns, 2005) and is measured by women’s capabilities in health, education, employment, and participation in decision-making (Mohanty, 1988; Sen, 1999; Nussbaum, 2000, 2003; Holmstrom, 2002; Ibrahim & Alkire, 2007). Thus, women empowerment encompasses several key elements:

-

1.

The ability to make decisions related to household spending, investments, and savings, and to have control over household assets (Kabeer, 2001a, 2005; West, 2006; Khan et al., 2020; Amir-ud-Din et al., 2023).

-

2.

Self-confidence, self-esteem, and ability to participate in household decision-making processes (Zimmerman, 1995; Malhotra & Schuler, 2005; Misra et al., 2021).

-

3.

The ability to engage in income-generating activities and control over earnings and assets (Kabeer, 2001b; Duflo, 2012; Saha & Sangwan, 2019; Mehta & Sai, 2021).

-

4.

Control over their own bodies and resources for health decisions (Upadhyay & Karasek, 2012; Upadhyay et al., 2014; Stöckl et al., 2021; Haque et al., 2021).

-

5.

Social standing through education, earnings, property ownership, and community participation (Klasen, 2002; Malhotra et al., 2002; Bulte & Lensink, 2020).

These interconnected elements suggest that women’s empowerment is not achieved through isolated changes in any single dimension, but rather through cumulative progress across multiple domains, with earning capacity potentially serving as a catalyst for broader transformational change in women’s lives and social standing.

Women’s empowerment is achieved when women have full autonomy over their lives (Zimmerman, 1995; Kabeer, 1999; Mosedale, 2005; Tong, 2019). Dismantling patriarchal systems and economic structures that perpetuate gender inequality becomes critical for achieving women empowerment (Echols, 1989; Kabeer, 1994; Warren, 2000; Holmstrom, 2002; Derrida, 2016/1967). Traditional and socially constructed gender roles and institutional barriers that limit women’s opportunities and potential need to be challenged and changed for women to become empowered (Eagly, 1987; Rowlands, 1997; Parpart, 2004; Butler, 2006; Evans, 2016).

Income, self-worth, and household bargaining power

Marriage and family can be viewed as psychological real estate where disadvantaged women are marginalized by being confined to a limited space. This disadvantage stems primarily from societal and familial norms and is reinforced through legal, economic, and technological structures. To occupy a larger space, women must push through, jostle, or bargain with those who dominate this psychological real estate—husbands, partners, and in-laws. From this perspective, empowerment becomes the struggle to acquire more space within the psychological real estate of marriage and family.

The perception about a woman changes significantly when she starts earning money. Women who earn money are often perceived as independent, empowered, and capable (Lennon, 1994; Bittman et al., 2003). They are seen as contributors to the household and the economy, which can enhance their bargaining power within the household (Goetz & Sen Gupta, 1996; Hashemi et al, 1996; Agarwal, 1997; Salway et al., 2003, 2005; Kabeer, 2005; Anderson & Eswaran, 2009; Blau, Ferber, and Winkler, 2016). Money can serve as an even better bargaining chip when a woman’s contribution to family finances is significant, especially in households where the husband earns less or in poor households (Vogler & Pahl, 1994; Bertrand, Kamenica, & Pan, 2015; Majlesi, 2016).

However, the relationship between income and self-worth is not always linear. Women in high-earning positions may experience impostor syndrome (Clance & Imes, 1978). In societies where women’s worth is traditionally tied to their roles as caregivers rather than earners, income may have less impact on self-worth (Inglehart & Norris, 2003). In societies with strong traditional gender roles, women who earn money may be viewed as a threat to the male breadwinner norm (Kabeer, 1997; Rudman, 1998; Aizer, 2010), leading to a temporary increase in intimate partner violence (Schuler et al., 2017). Earning women may face stereotypes of being too ambitious or neglectful of their family responsibilities (Rudman & Phelan, 2008).

Women’s empowerment research in India

Women’s empowerment in India has been a subject of extensive empirical research due to the country’s complex socio-cultural landscape and persistent gender inequalities (Borooah, Diwakar, Mishra, Naik, & Sabharwal, 2014). Studies have primarily focused on gender equality in terms of household decision-making (Duflo, 2012), literacy and educational attainment (Drèze & Sen, 2013), health outcomes including sex-ratio, children’s health, and reproductive rights (Bloom, Wypij, & Das Gupta, 2001), labor force participation and wage gap (Galiè & Farnworth, 2019), access to credit (Field et al., 2010), and political representation (Bhalotra, Clots-Figueras, & Iyer, 2017).

Research has demonstrated that female literacy and higher education levels significantly increase women’s economic participation and decision-making power within households (Cherayi & Jose, 2016; Murugan et al., 2021; Chatterjee & Poddar, 2024). However, as Krishna (2018) points out, the focus on individual-level educational attainment often obscures the need for broader structural changes in educational institutions and labor markets. Studies have found that gender quotas in local governance have reduced gender bias in educational aspirations among adolescent girls (Beaman et al., 2012), though understanding how institutional changes interact with social norms remains crucial for creating lasting impact.

Research by Rao (2018) demonstrates how gender relations in North India are constantly renegotiated within existing power structures, suggesting that intervention-based approaches may need to better account for these dynamic social processes. Recent research has increasingly emphasized the intersectionality of gender with other social categories such as caste, religion, and region, revealing complex patterns of disadvantage that women face in India (Varghese, 2020).

The heavy reliance on NGO-implemented interventions deserves critical examination. While these initiatives often show positive short-term results, their dependency on external funding and limited scale raises questions about their potential for creating systemic change (Batliwala, 2015). Roy (2015) offers a compelling critique of what she terms the “NGOization” of women’s empowerment, arguing that the proliferation of funded programs has sometimes undermined rather than strengthened grassroots feminist movements in India.

Existing research has largely focused on either evaluating specific interventions, government schemes and microfinancing by NGOs (Swain & Wallentin, 2009) or examining particular aspects of women’s empowerment–primarily financial autonomy and decision-making (Pandey et al., 2019). Notably absent from the literature are studies examining the relationship between women’s contributions to household expenses or monetary resources and their overall empowerment status (Yount et al., 2019).

Methodological trends and limitations in existing research

Most studies measuring empowerment have focused on either paid employment, employment outside the family circle, or women’s entrepreneurial activities as causes, considering empowerment as an outcome measured primarily through four parameters: participation in household decision-making, freedom of movement, control over resources, and women’s attitudes towards domestic violence (Huis et al., 2017; Leder, 2016). While these parameters capture important aspects of empowerment, they may not fully reflect the complex reality of women’s lives, particularly in the Indian context.

The ability to earn money provides a monetary cushion and the means to leave demeaning and abusive relationships (Kabeer, 1997, 2005; Vyas & Watts, 2009). However, quantitative measures of empowerment in existing literature often fail to consider the incidence of emotional, physical, and sexual violence against women. This oversight limits our understanding of the relationship between economic empowerment and women’s safety within intimate relationships (Sharaunga et al., 2019).

Several methodological and conceptual limitations warrant attention. The predominant use of quantitative metrics and standardized surveys, while valuable for policy planning, often fails to capture the nuanced lived experiences of women across India’s diverse socio-cultural landscape. The widely used Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), for instance, rely heavily on household decision-making as a proxy for empowerment, potentially missing crucial dimensions of women’s agency and autonomy (Kabeer, 2021). This methodological constraint has led to what Cornwall (2016) describes as the “measurement imperative”—where complex social processes are reduced to simplistic indicators that may not reflect meaningful change in women’s lives.

Many studies uncritically apply Western frameworks of empowerment to the Indian context, raising questions about their cultural appropriateness and validity (Narayan, 1997; Mohanty, 2003). As Chakravarti & Krishnaraj (2020) argue, the dominant paradigms of empowerment research often fail to account for the specific historical and cultural contexts that shape gender relations in South Asian societies. This critique is particularly relevant when considering how caste hierarchies intersect with gender to create unique patterns of marginalization that may not be captured by conventional empowerment metrics (Rege, 2013; John, 2015).

The emphasis on intervention-based research, while pragmatic, has led to a disproportionate focus on measurable short-term outcomes at the expense of understanding deeper structural barriers to empowerment. For example, while numerous studies document the impact of microfinance initiatives on women’s financial inclusion (Chattopadhyay & Duflo, 2004; Field et al., 2010), few examine how patriarchal social norms might limit the transformative potential of such interventions (Naved et al., 2018).

While the overall balance of research (Kibria, 1995; Kabeer, 1997, Endeley, 2001; Quisumbing & Maluccio, 2003) suggests that earning power does have the possibility to make a woman more empowered, methodological limitations have constrained our understanding of this relationship. Many studies rely on small sample sizes, focus on specific geographic areas, or use limited indicators of empowerment. Moreover, the interaction between women’s earnings and household wealth status remains understudied, particularly in the Indian context where social and economic hierarchies significantly influence gender dynamics.

To address these methodological gaps and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between earning money and women’s empowerment in India, this study employs a robust methodological approach using nationally representative data. The following section details our data sources and analytical methods.

Data and methods

Data source and sample characteristics

We use the India Standard DHS, 2019-21 Dataset (2021). The survey is part of the internationally comparable and standardized Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) Program, funded by USAID, UNICEF, WHO, and other international agencies. The survey instrument is revised and updated for each round of data collection. Variants of the questions included in the DHS survey instrument have been used by various researchers over the years. Conversely, variants of questions used in primary studies conducted by these researchers have also been included in the list of indicators in the DHS program. Published research reviewed for the present study that includes variants of the DHS indicators is presented in Table 1.

The survey covers 636,699 nationally representative households, with interviews completed for 724,115 females and 101,839 males. The females surveyed are between the ages of 15 and 49, including those currently living in union and those who have never married or are not currently living in union. The subset of women respondents used for the present study is extracted using three sequential filters.

The first filter selects only those respondents who are currently living in union, as questions regarding intimate partner violence are applicable only to them. Since missing values would make it impossible to categorize respondents as either empowered or not empowered, subsequent filters aim to minimize instances of ‘no response’ by selecting only those respondents who answered the question about their working status and, from among them, only those who responded to questions about domestic violence. Additionally, we exclude from our analysis cases where both the woman and her husband had no income during the reference period (income here is considered only as cash or a mix of cash and kind; earnings in kind only are not considered as income). This restricts the number of cases analyzed to 48,759 for the purpose of the present study.

The sample exhibits a stark urban-rural divide: 75.1% of respondents reside in rural areas. This rural majority also reflects a higher incidence of poverty, with 54.3% of rural respondents belonging to poorer households, compared to just 23.6% in wealthier households. This rural-urban disparity is further accentuated in urban settings, where a substantial 72.0% of respondents are from wealthier households, and only 11.4% are from poorer ones.

The youngest respondent in the sample is 16 years and the oldest is 49 years old; the median age being 33 years. A quarter of the women are below the age of 27 years and another quarter above the age of 39 years, indicating a relatively young cohort. Nearly half (47.5%) of the households consist of four or fewer members, with the median household size being five. Male heads dominate household leadership, with only 13.1% of households headed by women (Table 2). This is consistent across wealth categories.

Educational attainment varies significantly between the respondents and their husbands, with 28.1% of the women having no formal education, compared to 16.7% of their husbands. Most women (46.1%) have attained secondary education, yet only 11.3% have higher education, limiting their access to skilled employment opportunities and potentially reinforcing traditional gender roles.

The nature of women’s employment varies considerably (Table 3). Only 35.5% are engaged in gainful work, a stark contrast to the 97.2% employment rate among their husbands. Among employed women, agriculture is the dominant sector, employing 53.1% of working respondents, followed by skilled and unskilled manual labor (18.3%), while professional, technical, or managerial roles account for only 7.7% of employed women. While 58.6% of employed women work year-round, a substantial 36.5% are engaged in seasonal work, with agriculture accounting for the highest proportion (73.7%) of seasonal workers.

An examination of employer types and payment structures (Table 4) reveals that 79.5% of employed women work for family members or relatives. This high proportion of family-based employment is associated with concerning payment practices: 17.1% of employed women receive no payment for their work, with 87.2% of these unpaid workers employed by family members or relatives. Among those who are paid, 69.7% receive cash payments, 10.3% receive a mix of cash and in-kind payments, and 2.9% are paid solely in-kind. In contrast, men’s employment shows greater diversity and stability. While agriculture remains a significant employer (35.8%), there’s a more even distribution across sectors, with 30.4% in manual labor and 10.1% in clerical or higher positions.

The caste composition of the respondents reflects India’s complex social stratification, with Other Backward Classes (OBC) forming the largest group (41.0%), closely followed by Scheduled Castes and Tribes (SCs/STs) at 39.5%. The general category, representing upper or forward castes, comprises 18.9% of the sample. In terms of religious affiliation, most respondents are Hindu (76.8%), which is consistent with the national demographic distribution. However, Muslims, who make up 11.7% of the sample, are notably underrepresented compared to their national population share of ~17%. In contrast, Christians, at 6.6%, are overrepresented compared to their national average of just below two percent.

Quantification of women empowerment

The Indian DHS survey questionnaire for women comprises over 542 questions divided into 11 sections. Section IX, titled “Husband’s Background and Woman’s Work,” includes 47 questions covering topics such as the husband’s education and occupation, the woman’s life in the family, her financial position, freedom of movement, and (for married women) her attitude towards her relationship with her intimate partner. Section XI, titled “Household Relations,” contains 40 questions primarily focused on women’s experiences of domestic violence—emotional, physical, and sexual—by an intimate partner or husband.

We use a selection of questions from these sections, based on the literature survey, to measure the empowerment status of the women respondents (Table 1). We group the selected survey questions into categories representing different aspects of empowerment: financial autonomy (fa), bodily autonomy (ba), participation in household decision-making (fdm), marital rights (mr), attitude towards intimate partner violence (att_ipv), incidences of intimate partner violence (inc_ipv), and recognition by peers (ss). Intimate partner violence is further subdivided into instances of emotional, physical, and sexual violence. Following Basu & Koolwal (2005) and West (2006), respondents are assigned scores of 0 or 1 based on their responses to the questions. A score of 1 is assigned if the response indicates that the respondent has at least some say in the issue at hand; a score of 0 is assigned when the respondent has no say in the matter at all (see Table 1).

Women are considered to have achieved adequacy in a particular aspect of empowerment if they meet or exceed the threshold score set for that category. Threshold scores vary by category: for financial and bodily autonomy, 50% of the maximum score is sufficient; for participation in household decision-making, 60% is required. For marital rights, attitudes towards, and incidences of intimate partner violence, a 100% score is necessary. We maintain that wife-beating is unjustifiable under any circumstances, and that women have unfettered reproductive rights. Additionally, since social standing among peers is measured by a single indicator, only a score of 100% indicates adequacy in this aspect. A woman is considered empowered (dependent variable) if she achieves adequacy in five out of the seven aspects of empowerment. The earning status (independent variable) of the women is used to categorize them into two groups: those who are currently earning or have earned money during the last 12 months from the date of the interview, and those who have not earned at any point during the same period.

Hypotheses and tests

We test three hypotheses. First, the proportion of empowered women is higher among those who earn money compared to those who do not. Second, the odds of being empowered are greater for women who earn money than for those who do not. Third, household wealth moderates the effect of earning status on women’s empowerment. Specifically, earning women from the poorest households have higher odds of being empowered compared to earning women from the wealthiest households. Additionally, we examine the hypothesis that earning money is positively associated with women making more empowering choices and exercising their rights. This could lead to a lower tolerance for intimate partner violence and a reduction in its incidence.

The first hypothesis is tested using a proportion difference test. For the second hypothesis, we calculate the odds of being empowered as a result of earning money by conducting a logistic regression, with money-earning status as the predictor variable and categorization as empowered (or not) as the outcome variable. The third hypothesis suggests that poorer households place more value on the money earned. To test this, we compare the odds of being empowered due to earning money between women from the poorest and richest households. We achieve this by splitting the cases analyzed using the wealth index from the DHS dataset, which ranks households from poorest to richest based on assets. Next, we perform a Bayesian logistic regression for each wealth class and compare the odds of being empowered across these categories. Additionally, we examine whether responses to survey questions differ significantly between women who earn money and those who do not, using the Chi-Square Test of Association between two categorical variables.

Using the Bayesian approach enables us to specify a higher prior probability of empowerment for women from poorer households when testing the third hypothesis. We use the same approach for testing the first two hypotheses, although these hypotheses do not require us to specify prior probabilities other than being equally likely. When the priors are equally likely, they do not influence the posterior distribution, making the analysis resemble a frequentist approach (Lemoine, 2019). Frequentist analyses can be viewed as a special case of Bayesian analysis where the priors are non-informative or uniformly distributed (Sidebotham, Barlow, Martin, & Jones, 2023).

Empirical results

To understand the basic relationships, we calculated tetrachoric correlations between women’s earning status, seven aspects of empowerment, and the final empowerment status. We employed the ‘psych’ package version 2.3.9 (Revelle, 2023) in R 4.3.2 (R Core Team, 2023) for these calculations.

All observed correlations were generally weak (Fig. 1). Notably, attitudes towards intimate partner violence (att_ipv) and actual incidences of intimate partner violence (inc_ipv) exhibited negative correlations with women’s earning status. This suggests a complex relationship that warrants further investigation.

Heatmap of the tetrachoric correlations between earning status of women and the seven aspects of their empowerment.

Group differences in empowerment indicators

We next examine the measures of association for specific empowerment indicators, comparing women who earn money to those who do not.

Autonomy in mobility

The proportion of women in the money earning group who are allowed to visit places alone is consistently higher than that of the non-earning group with large and statistically significant differences (Table 5). This points to a greater degree of mobility and autonomy among earning women.

Attitudes towards and experiences of intimate partner violence

Women who earn money not only show a higher acceptance of intimate partner violence across various scenarios but also report experiencing higher rates of violence compared to non-earning women. These differences are statistically significant and often substantial. Tables 6 and 7 presents this somewhat counterintuitive but consistent pattern across all scenarios presented.

The scenario eliciting the highest justification for intimate partner violence in both groups was “disrespect for in-laws,” with 35.8% of earning women and 28.5% of non-earning women considering violence justified. Conversely, “refusing sex” received the lowest justification (12.7% of earning women vs. 9.3% of non-earning women). The largest disparity between the groups was observed for “neglecting house or children,” where 31.4% of earning women justified intimate partner violence compared to 23.5% of non-earning women—a difference of 7.9 percentage points. This substantial gap suggests that earning women may feel a heightened sense of responsibility or guilt regarding domestic duties, possibly due to the dual burden of managing both professional and household responsibilities.

Earning women reported higher incidences across all categories of violence: physical, emotional, and sexual. Slapping was the most frequently reported form of violence in both groups. A substantial proportion of women in both categories (29.0% of earning women and 21.6% of non-earning women) experienced this pervasive physical violence within intimate partnerships. Earning women reported experiencing severe physical violence—being “kicked or dragged”—at nearly double the rate of non-earning women (10.1% versus 5.3%). Sexual violence, while less common overall, still showed higher rates among earning women. For instance, 5.2% of earning women reported being forced into unwanted sex, compared to 3.4% of non-earning women. This pattern held true for other forms of sexual violence as well.

Marital rights, sexual health, consent, and autonomy

Women who earn money tend to exercise their marital rights to a lesser degree than those who do not earn (Table 8). Although majority of women across the groups assert their rights, nevertheless, the proportion of women in the money earning group who are not able to “refuse sex” or “say no” to their husbands is higher than that in the non-earning group. The decision to use contraception presents an ambiguous picture: while joint decision-making about contraception is overwhelmingly the norm in both groups, earning women are statistically—though subtly—more likely to report having the main say in contraception decisions compared to non-earning women.

Decision-making power within the family

The association between a woman’s status in family decision-making and her status as earning member of the family is statistically significant across the empowerment spectrum (Table 9). Across both groups, joint decision-making is the most common pattern. Within each group, women having no say (decisions made solely by husband or others) are fewer than those who are sole or joint decision-makers. However, when comparing the groups, earning women are more likely than non-earning women to be sole decision-makers.

Control over earnings and spending

When it comes to deciding how to spend their own earnings, both men and women primarily make joint decisions (Tables 9 and 10). However, the proportion of men who solely decide how to spend their money is more than that of women who have sole control over their earnings. Also, among the group of women who earn money, while only 8.8% of husbands have no control over their earnings, the proportion of women who have no say in how their earnings are spent (14.8%) is almost double.

Financial autonomy and asset ownership

Financial autonomy, as reflected in independently managed cash or bank accounts, differs significantly between the groups (Table 11). While most women in both groups have some degree of independent financial control, the proportion is significantly higher among earning women. Furthermore, earning women are more likely to own a house and land (either solely or jointly) whereas non-earning women are more likely to own neither. Overall, the non-earning group has a higher proportion of women without ownership of key financial assets.

Access to loans and peer recognition

Earning women are more likely to have taken loans from self-help groups or other agencies compared to non-earning women. (Table 12). These loans typically rely on the borrower’s reputation among peers suggesting that a woman’s earning status enhances her social recognition and creditworthiness within her community.

Overall empowerment attainment

Finally, we examine the relationship between earning status and the overall empowerment attainment (Table 13). While only 22.2% of all respondents achieved adequacy in overall empowerment, this proportion is significantly higher among earning women compared to non-earning women.

Comparing overall empowerment proportions

We used the Logit Transforming Testing (LTT) approach of the Bayesian test of difference in proportions as implemented in the abtest package version 1.0.1 in R (Gronau, 2019) to compare the directional hypothesis H1 (more women are empowered in the money earning group than in the non-earning group) against the null hypothesis H0 (the proportion of empowered women does not differ between the groups). Since the evidence in the extant literature for earning money positively impacting empowerment of women is, at best, mixed, we employed a truncated normal distribution with (mu =0) and ({sigma }^{2}=1) under the alternative hypothesis.

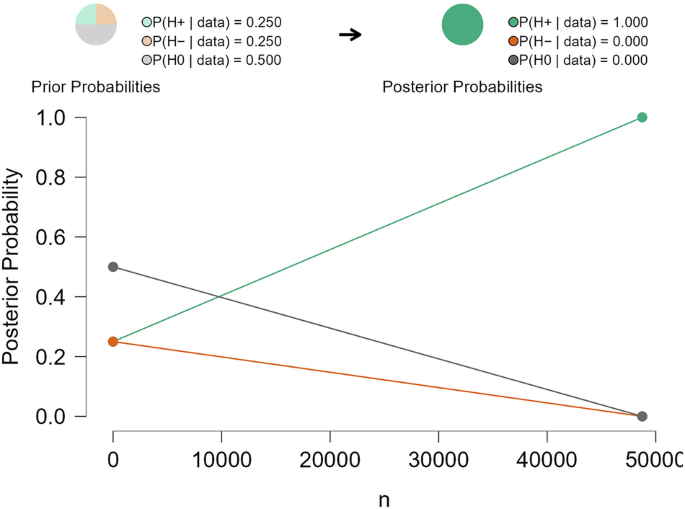

The observed sample proportions of 0.206 for the non-earning group and 0.255 for the money earning group indicate that more women are empowered in the money earning group than in the non-earning group (Table 14). The Bayes factor ({{BF}}_{10}=7.686{e}^{30}) supports the alternate hypothesis. Figure 2 traces the evidence for both the hypotheses sequentially. The evidence for the alternative hypothesis is overwhelming; data increases the plausibility of H1 from 0.25 to almost 1.00 whereas the posterior probability of H0 decreases from 0.50 to almost zero.

Sequential analysis of the posterior probabilities of the base and the hypothesized model.

To quantify the difference between the two groups, we estimated the odds ratio and plotted the prior and posterior distributions of odds ratio for the two-sided alternate hypothesis. Given that the posterior odds ratio is not exactly zero, it is 95% probable to lie between 1.265 and 1.382 with the median of 1.322 (Fig. 3). The heatmap of Bayes factor against prior distribution of effect sizes (Fig. 4) peaks around 0.25 indicating sensitivity to the prior normal distribution.

Prior and posterior distribution of odds ratios.

Heatmap plot of the Bayes factor against prior distribution of effect sizes.

Modeling the effect of earning status on empowerment

We conducted a Bayesian logistic regression using earning status as the predictor and empowerment status as the outcome variable comparing the odds of a woman being empowered if she earns money than if she does not. We employed BIC criteria and used beta binomial (1,1) as model priors (Table 15).

Although the BF10 value of 1.00 indicates neutral evidence in favor of H1 over H0, the P(M|Data) and BFM values provide overwhelming evidence with a high degree of confidence. This is also buttressed by the posterior inclusion and exclusion probabilities (Table 16). The data suggests that earning status is highly relevant in predicting the outcome (P(incl|Data) = 1.000) and finds no support for excluding it (P(excl|Data) = 0.000). The BFinclusion factor is extremely high (7.508 × 1029) also indicating strong evidence for including it.

Since the 95% confidence interval of earning does not cross zero (Fig. 5), it can be said with high degree of certainty that earning status has a positive effect on empowerment. The computed odds ratio implies that women earning money are 32% (mean odds ratio = 1.32; 95% confidence interval: 1.28—1.38) more likely to be empowered than those not earning money. Despite the high certainty of the parameter effects, the model has very low explanatory power (R2 = 0.003) implying that while the earning status model is better than the null, it still does not explain variability in data in any significant way.

Marginal distribution of posterior probabilities.

However, when we control for family wealth in the regression (setting beta binomial (3,2) as priors), more nuanced results emerge (Table 17). For a woman in the poorest household wealth category, the likelihood of being empowered is about 11% less (mean odds ratio = 0.89; 95% confidence interval: 0.60—1.32) than that of a woman from the richest household wealth category. But the confidence interval spans both sides of 1.0 suggesting a likelihood that is not much better than chance. Thus, household wealth does not seem to affect the state of empowerment of woman—the third hypothesis gets no support from the data.

Discussion

Existing literature presents mixed evidence on the relationship between earning money and aspects of women empowerment. Holvoet (2005) argues that women who have their own money are more likely to be involved in decision-making within their households. This can help to reduce male dominance and create a more equitable relationship. Some studies suggest that access to money or earning income (through participation in microfinance groups or targeted transfer payments) decrease domestic partner violence (Goetz & Sen Gupta, 1996; Hashemi et al., 1996; Hidrobo, Peterman, & Heise, 2016).

However, the present study exposes a clear divide in how earning money affects different areas of women’s psychological real estate. The impact of earnings is not deterministic; rather, it varies across this space, clearly distinguishing between intimate and non-intimate domains. In intimate spaces, earning money does not seem to shift power dynamics in women’s favor, whereas in non-intimate spaces money appears to facilitate the expansion of territories.

The results of the present study agree with others (Bates et al., 2004; Ahmed & Hossain, 2020; Ali & Kiani, 2021) that found higher incidences of intimate partner violence faced by wage-earning women. In general, women who earn money are comparatively more likely (“often”, “sometimes”) to experience various forms of abuse (emotional, physical, sexual) than those who do not earn money. The ability to say no to sexual intercourse for certain reasons (husband has STD or multiple sex partners, wife is not in mood) is also negatively affected by women earning money. This is mirrored in the attitude towards intimate partner violence: proportionately more women in the money earning group justify husband beating his wife for certain ‘transgressions’. Earning money seems to make women cede ground to their husbands when it comes to marital rights and intimate partner relation.

Several factors may contribute to these counterintuitive findings. First, earning money may challenge traditional gender roles and power dynamics within households. Increased violence is perhaps a mechanism through which husbands try to increase their bargaining power and reassert control in intimate relationships—a sort of pushback to wives bargaining for more with her earned money (Eswaran & Malhotra, 2011). Also, economic stress within households with uncertain finances could potentially lead to increased tensions and conflict, manifesting in higher rates of violence against earning women.

Second, the higher acceptance of intimate partner violence among earning women might be a reflection of internalized gender norms and expectations. Despite their financial contribution, these women may feel an increased pressure to fulfill traditional roles and may view violence as a justified response to perceived failures in these duties. This is particularly evident in the high justification rates for scenarios related to neglecting household responsibilities.

Third, it is possible that earning women have greater awareness of their rights and are more likely to recognize and report various forms of abuse. This could partly explain the higher reported incidences of intimate partner violence among this group. However, this explanation does not account for the higher acceptance of violence in hypothetical scenarios.

Nevertheless, earning money does seem to provide for higher financial autonomy in terms of independent ownership of resources (money, bank accounts, house, land), greater bodily autonomy in the sense of freedom of movement beyond the confines of home and surroundings (market, healthcare facility, places outside community, cinema visits), and larger say in family decision-making (visit to relatives, healthcare, major purchases, decision to spend money). It even leads to increased recognition among peers as loan uptake from NGOs is primarily dependent on self-help groups based on mutual recognition and trust.

Conclusion

Analysis of the Indian DHS data revealed that: (a) women’s earning status and intimate partner violence-related variables are negatively correlated, (b) a significantly higher proportion of women in the money-earning group (25.5%) are empowered compared to the non-earning group (20.6%), (c) women earning money are 32% more likely to be empowered than those not earning, and (d) women from the poorest households show no significant difference in empowerment levels compared to those from the richest households. Overall, the results support a positive but limited relationship between earning status and women’s empowerment, with household wealth playing a negligible role.

While earning money is a good predictor of a woman’s overall empowerment status, it inadequately explains the complexity of the relationship between the two. Women’s financial participation does not inherently equate to empowerment in all its facets. Our findings suggest that financial independence alone is insufficient to change deeply ingrained social norms and attitudes regarding gender roles and violence—higher acceptance and incidence of intimate partner violence among earning women being the case in point.

Practically, this means that interventions designed to financially empower women, such as India’s national rural employment guarantee program—arguably the world’s largest, where women constitute about two-thirds of the beneficiaries (Press Information Bureau, 2024)—do little to change their empowerment status in intimate spaces. To be effective, policies and interventions should focus not just on increasing women’s income, but also seek to transform power relations. They should address cultural norms and attitudes that limit women’s opportunities and choices, and engage men and communities in discussions about gender equality. Empowerment strategies should consider the intersecting forms of discrimination and oppression that women face due to their identities in intimate and non-intimate spaces.

This dichotomy challenges simplistic narratives about the relationship between economic participation and empowerment. Empowerment is deeply influenced by cultural norms, traditional gender roles, and internalized beliefs that manifests differently across various domains of a woman’s life. Future research should examine the mechanisms behind these disparate effects. This could include longitudinal studies to examine how attitudes and experiences change over time, as well as qualitative research to gain deeper insights into the lived experiences of women as their economic roles evolve within traditional social structures in both public and private spheres.

Responses