Drifting fish aggregating devices in the Indian ocean impacts, management, and policy implications

Introduction

Over the past three decades, tropical tuna purse seine fisheries have adopted and become increasingly reliant upon artificial drifting fish aggregating devices (dFADs) to increase their harvest efficiencies. In the Indian Ocean, each purse seine vessel may legally deploy hundreds of dFADs each year to aggregate fish, making them easier to harvest1. Between 2020 and 2022, the deployment of dFADs significantly increased from 25,690 to 72,068, with the daily count of satellite-monitored buoys within the large-scale purse seine fishery fluctuating between 8408 and 11,5362. The utilization of dFADs has sparked intense debate due to its ecosystem impacts that include growth overfishing of tuna populations3, ghost fishing4, and plastic pollution5,6,7,8 As a result, the utilization and management of dFADs have increasingly been negotiated in Regional Fisheries Management Organization (RFMOs) meetings.

Floating objects at sea tend to aggregate tuna (skipjack, yellowfin juveniles and bigeye juveniles), and tuna-like species such as sharks and billfishes. This facilitates high volumes of catch and allows purse seine fleets to dominate tuna harvests globally, but in some cases, may also contribute to population decline. Specifically, a staggering excess of 95% of yellowfin and bigeye tuna catches associated with dFADs are juvenile tunas9, with data by gear type highlighting that industrial purse seine fleets take the largest regional harvests of the Indian Oceans’ yellowfin tuna stock, a population that has been overfished since 2015.

Moreover, dFADs result in higher catches of vulnerable non-target species compared to targeting free-swimming schools of tuna5,6,8,10,11,12,13,14. Scientists have expressed concerns that the use of dFADs, especially their impact on tuna behavior, also creates uncertainties in scientific assessments through breaking assumptions of typical CPUE based-statistical abundance estimates while also causing a “basin effect” with hyperstability of catches that can obscure stock declines15,16,17,18. Assessments of these concerns have been complicated by factors such as seasonal fluctuations in dFAD use and stock abundance, differing dFAD designs, and the proliferation of dFAD use, meaning it is now practically impossible to compare data with pre-FAD baselines19,20.

Finally, concerns about oceanic plastic debris have become more pressing21, with some legal experts reporting that the current use of dFADs may violate international marine pollution laws, positioning harvests around these devices as potentially resulting from Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing8,21,22. Studies have identified dFADs as a major source of ALDFG7,13. Their impacts include habitat degradation, food web disruption, and direct harm to marine species4,5,23,24. Studies have suggested that <20% of deployed dFADs may be eventually retrieved25, and thus the abandonment of dFADs at their scale of use results in global-scale oceanic plastic pollution24. In the western central Pacific Ocean region (WCPO), the statistics are worse, with likely less than 10% of deployed dFADs being retrieved, leading to a majority of these satellite-tracked devices being lost or intentionally abandoned26. This pollution is burdening coastal states financially, as they often bear the burden of clean-up costs7,27,28, while causing ghost fishing and other ecosystem impacts that can continue for decades after abandonment. These issues have brought over 100 organizations together to demand improved dFAD management among purse seine fisheries operating in the IO29.

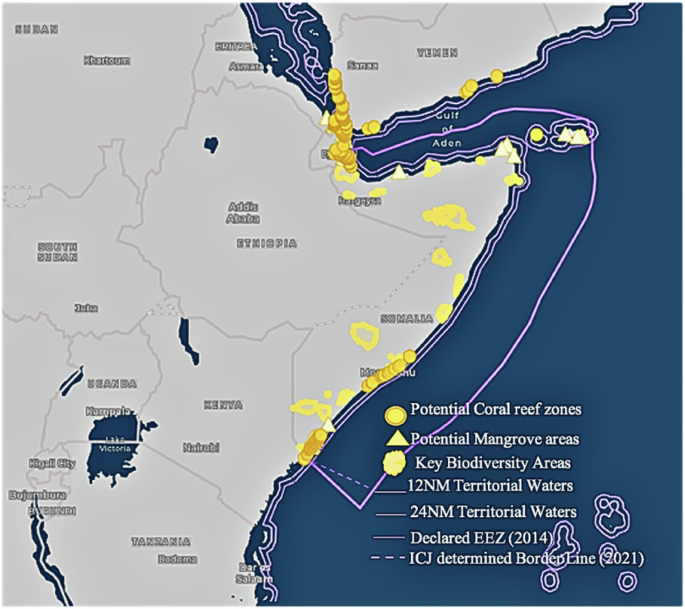

To understand the extent and impact of dFAD use, this study will investigate the prevalence of ALDFG in one area of the Indian Ocean where dFAD abundance is anecdotally high: within the waters of Somalia (Figs. 1 and 2). The choice to focus on the Federal Republic of Somalia is grounded in the region’s notable marine biodiversity, especially the rich populations of tropical tunas; the inherent fragility of its marine habitat’s biodiversity30,31,32 and emerging data suggesting that the Somali coastline might be a major accumulation zone for ALDFG, as underscored by33. We begin with a review of the use, impacts, and governance of dFADs in the Indian Ocean generally, and then dive into the specifics of dFADs in the waters of East African coastal States. We then describe the study methods, followed by results, and a discussion of the results with consideration of the governance challenges facing member States of the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC).

This map illustrates the marine biodiversity zones and territorial waters of Somalia, including key ecological areas and legal maritime boundaries. Potential Coral Reef Zones: indicated by yellow circles, these areas are identified as potential habitats for coral reefs. Potential mangrove areas: represented by yellow triangles, these regions are potential habitats for mangrove forests. Key biodiversity areas: highlighted in yellow, these areas are crucial for maintaining biodiversity. 12NM territorial waters: marked with a solid light blue line, these waters extend 12 nautical miles from the baseline, within which Somalia exercises sovereignty. 24NM territorial waters: indicated by a dashed dark blue line, these waters extend 24 nautical miles from the baseline, encompassing Somalia’s contiguous zone. Declared EEZ (2014): Represented by a solid purple line, this is the Exclusive Economic Zone declared by Somalia in 2014, where it has special rights regarding the exploration and use of marine resources. ICJ determined border line (2021): shown as a dashed purple line, this border line was determined by the International Court of Justice in 2021, defining maritime boundaries. The map underscores the environmental and geopolitical significance of these marine regions, highlighting areas that are critical for conservation and sustainable management. ©Secure Fisheries (Project Badweyn Map). Used with permission. This image is intended for readers to visualize the Project Badweyn Map. The permission to use and adapt this image has been obtained in writing.

This figure showcases various abandoned, lost, and discarded fishing aggregating devices (dFADs) recovered along the coast of Somalia. Top left image: displays a cluster of buoys and nets entangled with seaweed, washed ashore. Top right image: shows a large, dilapidated dFAD structure on the beach, illustrating the size and complexity of these devices. Bottom left image: features a small boat with recovered dFAD debris, highlighting the efforts of local fishers in collecting these abandoned gears. These images underscore the environmental impact of abandoned dFADs on Somali coastal ecosystems and the ongoing recovery efforts.

The IO is a diverse and productive ecosystem, home to almost one-third of global coral reef cover and over 40,000 km2 of mangroves34. For the 38 countries whose Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) encompass parts of this ocean, this biodiversity provides invaluable resources that have large contributions to economies and livelihoods. Tuna resources in the Indian Ocean represent a vital economic asset for coastal states, offering significant contributions to their economies through fishing activities, employment, and export revenues. In 2021, the catch from large-scale purse seiners using drifting floating objects amounted to 410,000 tons. This figure represents 87% of the total industrial purse seine catch, and 35% of the total catch of the IO tropical tunas35. These statistics underscore the predominant role of dFADs in the purse seining sector and their significant contribution to overall tuna catch in the IO. In the Western Indian Ocean, the total fish hold volume of purse seiners utilizing drifting dFADs is reported to be 97,000 cubic meters35. Coastal communities within these states are intertwined with the ocean, critically relying on its health and the sustainability of its resources for their day-to-day survival. The current prevalence of dFAD use may threaten not only sustainability of the resource base (tuna), but also local livelihoods and the economic development opportunities of IO coastal states28. Here we summarize the development of dFADs in the Indian Ocean and speak to the challenges of governing them in this region.

dFADs have been increasingly used by tropical tuna purse seine fisheries since the mid-1990s. These artificial floating objects, designed to aggregate fish, have seen a significant increase in their use throughout the Indian Ocean, rising from an estimated 2250 in use in October 2007 to 10,300 by September 2013—demonstrating at least a fourfold increase in the number of dFADs over a 7-year study period36. Similarly, an increase from 25,690 a year in 2020 to 72,068 in 2022 has been noted36. On an average day, the number of different satellite-tracked buoys, monitored by the large-scale purse seine fishery persisted between 8408 and 11,53636. In the Indian Ocean, the EU purse seine fleet relies heavily on dFADs, with over 80% of their sets made on dFADs. The increase in dFAD use over the past two decades has transformed fishing practices and prompted concerns over environmental impacts, necessitating sustainable management practices to mitigate adverse effects on tuna stocks and the open-ocean ecosystem.

The development of dFADs has considerably improved the searching efficiency of purse seiners, as noted by researchers5. Unlike targeting free-swimming schools, which often lead to overfishing and necessitate daylight hours for location, dFADs offer a distinct advantage by allowing for quick location and minimization of search time and operating costs. dFADs can be pinpointed at any time of day using a computer screen, to commence fishing operations at dawn. The latest generation of dFADs is equipped with echosounders, providing skippers with daily or hourly estimates of biomass beneath the buoy. This feature enables skippers to confirm the presence of a school beneath an FAD before visiting it, further enhancing efficiency5. Additionally, in some oceans such as the Atlantic and Indian, supply vessels collaborate with purse seine skippers to deploy and monitor dFADs using sonar and other fish-finding technologies, exemplifying the integration of advanced tools in modern fishing practices. This surge reflects a shift in fishing techniques and underscores the growing reliance on technological innovations to enhance fishing efficiency in the dynamic marine environment of the Indian Ocean. Furthermore, enhanced capabilities have led to a deeper understanding of the habitat characteristics and dynamics of pelagic species aggregated under dFADs, which is key to improving fishing practices37.

As the amount of dFAD use has increased, so too has the absolute volume of dFADs that remain uncollected, adding to the ocean’s burden, exacerbating the plastic pollution crisis, and affecting marine ecosystems21,24,27,38. dFAD pollution does not just litter the ocean floor; it may also introduce harmful entities like microplastics into marine food chains, posing risks to both marine life and humans39. The significant pollution clean-up costs are also inequitably borne by coastal states7,27 as the fleets deploying dFADs are often distant water fleets (for example the EU), but the abandoned dFADs typically end up beaching or polluting the waters of developing coastal States.

Not only has dFAD use increased, but dFADs themselves have undergone significant technological evolution in recent years. These innovations include the transmission of real-time data on biomass aggregation via satellite communications. Additionally, dFADs may now incorporate Artificial Intelligence to optimize fish aggregation by providing real-time data on fish biomass and species composition beneath the dFAD, theoretically enabling the fleets to target specific species and reduce bycatch. Despite these capabilities, there remains a substantial gap in the application of this technology for sustainable fishing practices, with most fleets prioritizing catch volume and financial value over ecological considerations.

Furthermore, echosounder technology has advanced to the point of being able to discern species compositions beneath dFADs, allowing purse seine fleets to operate more efficiently and continuously. These species differentiation capabilities should enable industrial purse seine fleets to avoid setting on dFADs dominated by juvenile tunas or those with a high abundance of aggregated bycatch species, but evidence of fleets using this technology to proactively fish more sustainably rather than to maximize their overall multi-species catch volumes and financial value, remains lacking. This underscores a critical need for further targeted research to explore how advanced technological improvements of echosounders are utilized in the field and its potential for promoting sustainability in commercial fishing operations.

Despite the technological advancements in dFADs, there are ongoing concerns regarding their role in IUU fishing activities, especially in the Indian Ocean40. Advanced geo-location tools and echosounder buoys also present strategic deployment and irregular use of tracking technologies and pose challenges in fisheries management. In the WCPO, operational factors, particularly dFAD deployment strategies, have a significant impact on the occurrence of beaching events26. In regions like Somalia, where regulatory oversight is still developing, the potential of these devices to facilitate IUU fishing is of particular concern. Such technologies allow for precise control and monitoring of dFADs, potentially enabling them to be used in unauthorized areas or in ways that evade regulations. For instance, suspected strategic and covert dFAD deployments have been noted, while intentionally sporadic use of vessel tracking technologies pairs with dFAD issues to likely facilitate IUU fishing activities by industrial purse seine fleets, including within the Somalia EEZ41. Studies also indicate that a substantial number of dFADs remain adrift in the Indian Ocean, often entering EEZs of countries without official permission6,18,33. Many of these dFADs are abandoned outside designated fishing grounds, posing risks to marine ecosystems, and potentially affecting the migratory routes of tunas and other pelagic species.

Governance of dFADs is a growing and complex challenge. Firstly, multi-level governance is in place due to the migratory nature of tuna species. As highly migratory species, their governance falls under regional international cooperative management structures through RFMOs42, but tuna fisheries also tend to be managed via domestic regulations or license conditions attached to vessel practices. The IOTC is the RFMO with an Area of Competence spanning the Indian Ocean and, therefore, mandated to ensure sustainable fisheries for tuna and tuna-like species in the study region. Established in 1996 under the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the IOTC’s primary role encompasses the conservation and sustainable management of tuna and tuna-like stocks within this region. The IOTC’s responsibilities involve conducting scientific research, establishing catch limits, and formulating strategies to minimize bycatch and preserve marine ecosystems. With 30 member countries and territories, including both Indian Ocean coastal States and distant fishing nations, IOTC’s objective is to encourage sustainable management of fisheries within its remit.

To date, the current governance of FADs by RFMOs, including in the Indian Ocean, is widely regarded as insufficient on a global scale; for example, Indian Ocean studies including those by5,6,8, have critically evaluated the efficacy of RFMOs in managing these devices and found effective management lacking. Some critics have specifically highlighted the inadequacy of the IOTC’s measures, especially when contrasted against the magnitude of overfishing threats and addressing the ramifications of dFAD use and the regional importance of ensuring the sustainable use of tuna species in this region9. The IOTC’s Resolution 19/02, for instance, only pertains to actively fished or followed dFADs, meaning it does not cover the many dFADs that already makeup ALDFG throughout the Indian Ocean and may still be opportunistically fished whenever they are encountered, regardless of the status of their satellite communications8. Most recently, two thirds of IOTC members endorsed the implementation of Resolution 23/02 to improve dFAD management in the region. Unfortunately, in the following weeks, one-third of IOTC member States were politically bullied into objecting to the same Resolution, which would limit dFAD numbers, improve reporting responsibility, and close parts of the region to dFAD fishing for 72 days. With one-third objecting, the measure becomes non-binding and essentially ineffective.

From a tuna sustainability standpoint, the most pressing concern of dFAD use centers around the disproportionate aggregation of juvenile fish. By skewing the catch towards juvenile fish, there’s a significant reduction in the average size of the caught fish, limiting the yield per recruit13,14. This also means that fisheries targeting adult fish, for example, Japanese longlines, have their potential yield reduced if not enough juveniles are left to grow into adults. Furthermore, there is a hypothesis that dFADs set up ‘ecological traps’43,44. Fish, especially migratory species, find themselves drawn to these structures, often leading them away from their natural habitats, migration routes, and affecting their overall health45,46.

Fishing has been a crucial source of livelihood for many coastal communities bordering the Indian Ocean. In some countries, the fisheries sector is seen as a growing sector that can bring economic prosperity and development. However, the introduction of modern fishing technologies, such as dFADs, raises concerns about the long-term potential of the marine ecosystem to support these economies into the future13. A considerable number of these dFADs, once released, appear to end up stranded in the territories of the East African coastal states33. Furthermore, there’s increasing concern over the legality of certain fishing practices8,22,40. The relative lack of data reporting about dFAD numbers, locations, and use is also being maintained through questionable claims of “commercial confidentiality” coming from the purse seine industry. For example41, have pointed out specific instances where purse seine fleets have overstepped their boundaries and engaged in unauthorized fishing within the waters of coastal states, but investigations have been complicated by the seemingly intentionally maintained scarcity of dFAD data and lacking transparency in purse seine fleet operations.

The study conducted by ref. 33 provides valuable understanding regarding the trajectories of drifting dFADs. Their research reveals that a notable proportion of dFADs diverge from their initial fishing areas within the IO and subsequently approach within approximately 50 kilometers of a port. This proximity is maintained on average for just over 3 days. More fulsome dFAD trajectory data can improve our understanding of ghost fishing, beaching events, and the broader ecosystem impacts of abandoned or lost dFADs. Overall, detailed trajectory analysis is vital for developing effective fisheries management strategies and mitigating the environmental impacts of dFADs38. This may suggest that collecting these drifting dFADs might not only be feasible but also financially viable, particularly given the extensive ecological harm these devices may cause if left in the water.

Tropical purse seiners seem to have a targeted strategy wherein they release these devices outside the EEZ of Somalia, typically during the period from June to August33. The underlying intention is to exploit the onshore currents, positioning the dFADs to drift through the primary fishing regions situated within Somalia’s EEZ before they later drift out of Somali waters with valuable tuna aggregated beneath them for harvesting. This seemingly calculated move is also a tactic to bypass the potent monsoon-induced currents that dominate from July to December, as detailed by ref. 47. These currents, if not strategically avoided, could inadvertently push the dFADs further eastward. Given the patterns of marine currents, the peak fishing season using dFADs in this part of the Indian Ocean falls between August and October.

The issue with deploying dFADs related to IUU fishing centers on their unregulated movement near the Somalia EEZ. When these dFADs drift into Somali waters without authorization and subsequently return to the high seas, they pose a significant challenge. Often, the fleets associated with these dFADs may not report to the IOTC when the devices stray from designated fishing zones into prohibited EEZ areas, only to drift back into international waters where unrestricted fishing resumes. This allows fleets to exploit potentially valuable resources gathered by the dFADs during their unmonitored journey through the EEZ. For instance33, document the trajectories of dFADs that, between 2012 and 2018, originated from areas adjacent to the designated fishing zones near the Somalia EEZ. Notably, 1641 of these dFADs were lost in Somali waters. Their path frequently skirts close to the EEZ particularly around Mogadishu port and extending towards the coastlines of countries like Tanzania and Mozambique.

This unrestricted movement of dFADs reveals a stark trend: a significant majority—ranging from 30% to as high as 100%—definitively leave the designated fishing grounds, moving beyond a 50-kilometer boundary from the ports in the East African coastal states33. This migration pattern emphasizes the strategic importance of these areas for fishing operations. Such movement not only makes the Somali coast a nexus of marine activity but also highlights it as a crucial epicenter for illegally discarded and systematically abandoned dFADs in the vast stretch of the Indian Ocean. There is a maintained lack of accountability for ownership and responsibility to compensate for the true ecological cost of such practices, which has resulted in conflicts with conservation goals and management arrangements48. These arrangements include limits on the number of active dFADs, time-area deployment restrictions, and the mandatory use of biodegradable materials in dFAD construction48.

To understand the magnitude and ecological consequences of the utilization of dFADs, we assess the prevalence of ALDFG within a particularly impacted segment of the Indian Ocean, specifically the waters of Somalia. The rationale for concentrating on Somalia is multilayered, underpinned by the nation’s remarkable marine biodiversity, which is notably characterized by substantial populations of tropical tunas. This decision is further justified by the inherent vulnerability of the region’s marine biodiversity, as documented in works by refs. 30,31,32. Additionally, emerging evidence posits the Somali coastline as a principal deposition zone for ALDFG, a notion supported by the findings of ref. 33.

Results

Over the study period, 63 dFADs were recovered as stranded within the study area, which was 150 km of coastline.

The study provides a robust estimate of the number of dFADs that potentially drift into the Somali EEZ annually. Despite the variation in the area of the study shelf, the final estimate of the total number of recovered dFADs for the entire Somali EEZ remains consistent, demonstrating the reliability of the proportional density calculation method. This assessment offers valuable insights for policymakers and stakeholders in managing and mitigating the impact of abandoned, lost, or discarded dFADs in the Somali EEZ.

To convert this to an estimated total number of recovered dFADs per year, we multiplied it by the total number of lost, abandoned, and discarded dFADs in the Somali shelf area per annum. This gave us an estimated total number of 1395 dFADs that potentially drift into Somalia’s EEZ as ALDFG per year. Following some of the ALDFG dFADs recovering during the project period. (Fig. 3)

The image depicts a local fisherman recovering an abandoned drifting Fish Aggregating Device (dFAD) on the shoreline. The recovery of such devices is crucial to mitigate their environmental impact and prevent navigational hazards.

Of the 63 dFADs recovered, 43 (68%) were recorded as beached after becoming stranded ashore and no longer free-floating at sea. Of the total beached dFADs found during the assessment, about 17% of beaching events occurred in mangrove habitats, with half (49%) of events occurring on sandy beaches. The remaining 33% dFADs had the final positions in shallow coastal waters, with most being recovered within 500 m from the shoreline on coral reefs or seagrass beds. Some beached FADs possibly impacted more than one type of habitat; for example, in some locations, a final position in the mangrove habitat would require the dFAD to first pass over coral reef areas to reach that position. In this case, over 50% of the dFADs were in this position and, therefore, had unknown impacts on coral reefs or seagrass beds before beaching on the shoreline. However, Mogadishu (Liido beach) showed the highest number of beaching habitats, with half (49.21%) of all dFADs strandings being there, which also happens to be a sandy beach. Below are photos of an ALDF dFAD retrieved by local fishers during the project data collection (Fig. 3) and another abandoned dFAD underwater in the Indian Ocean, with synthetic rope and nets attached (Fig. 4).

This underwater photograph shows an abandoned drifting Fish Aggregating Device (dFAD) submerged in the ocean. The image highlights the entanglement hazards and potential environmental damage caused by these devices when left unchecked. It provides readers with an understanding of what dFADs look like underwater. © RainervonBrandis/iStock, used with permission. Stock photo ID: 175423896.”. This image is intended for readers to understand how dFADs look underwater. The permission to use and adapt this image has been obtained in writing.

Of the recovered dFADs, 59 included a satellite/operational buoy and, of these, 4 were lone buoys that were no longer attached to a dFAD structure (Table 1).

Using the 4 indicators of compliance as above, we found that, out of the 63 dFADs recovered during the project period, none were fully compliant with the regulations of Resolution 19/02. None of the buoys had the IOTC vessel registration included, the shade cloths were all either nets or meshed materials, also putting them in non-compliance.

The primary areas of non-compliance identified were the lack of UVI numbers on satellite buoys and the use of meshed materials, particularly in the rafts. Marking with the UVI is important for tracking FAD ownership and creating accountability. Instead of the number, many vessels appear to use abbreviations of their vessel name with varying degrees of clarity. The materials used to cover the raft of the recovered dFADs were mainly made of plastic material, with fishing nets and meshed shade cloth typically covering the surface. Substructures were often constructed of synthetic rope and netting hanging from the center of the floating raft to depths ranging from 14 m to 33 m, often with woven sacks, polystyrene tubes, or rolled and tied bundles of nets attached. The IOTC Secretariat reported a significant decrease in the use of fishing nets dFADs in the IO over the last two decades. By 2022, only 5% of dFADs were made with recycled fishing nets, compared to 76% in 2015, highlighting a major shift towards tracking systems and away from net-based constructions35,49.

Due to a lack of IOTC vessel ID numbers on dFAD buoys (as required through Resolution 19/02), despite device serial numbers being permanently marked in large writing on each buoy, only 56 dFADs could be assigned to a vessel with a reasonable level of confidence. According to the findings, 42% of the 56 dFADs identified were from Spanish-flagged vessels. Spanish fleets were responsible for the highest relative number of dFADs recovered in Somali waters through this study. The Seychelles accounted for the second-highest number of FADs, with 29% of the recovered devices originating from vessels with this flagged under Seychelles. It is likely that the beneficial ownership (In this context, ‘beneficial ownership’ refers to the individuals or entities who derive economic benefits from the deployment or use of dFADs in fishing operations. This article explores how this beneficial ownership influences fishing practices, sustainability efforts, and the conservation of marine resources [Gokkon, B. (2021, September 17). Mongabay.https://news.mongabay.com/2021/09/for-sustainable-global-fisheries-watchdogs-focus-on-onshore-beneficial-owners/]”) of the vessels as well as those flagged under other states, is directed toward the EU. Tanzania, France, and Mauritius had 9%, 8% and 1% dFADs associated with their vessels, respectively, Additionally, 11% lacked any clear mark that could enable tracing the dFAD to its responsible vessel (Table 2).

Discussions with Somali fishing communities during this study also exposed anecdotal evidence that there is a high probability that many more beaching events of dFADs may have occurred during the study period, but that they were not included in the analyses and rather were disassembled so their components could be used for various purposes (particularly the solar panels in buoys and ropes) by coastal communities. This highlights the need for ongoing monitoring38, and analysis to improve local fisher awareness of the recovery program and provide a more comprehensive understanding of dFAD use24, ownership, liability, and its impact on the marine environment in the IO.

Discussion

Our study’s finding suggests a significant prevalence of ALDFG dFADs with the Somali EEZ, with a notable portion of recovered dFADs showing signs of non-compliance. This suggests systemic issues in the adherence to and enforcement of dFAD management protocols in the IOTC regulations. The findings provide valuable insights into the potential abundance of dFADs that may continue to fish ‘illegally’ within the Somali EEZ, highlighting the urgent need for comprehensive monitoring and regulatory measures to address this issue. Somalia’s EEZ is large and proximate to the main purse seine fishing grounds of the Indian Ocean, and with that in mind, it is not surprising that the highest evidence of ALDFG is also concentrated along the Somali coastline.

This study tracked instances of ALDFG along a stretch of the Somali coast, as well as evaluated the compliance of these recovered dFADs with the IOTC Resolution 19/02. The outcomes of this research contribute to the rather new body of knowledge on the prevalence, impact, and need for management of ALDFG in Somali waters and, more broadly throughout the Indian Ocean. During the project period from March and August–to December 2022, 63 dFADs were recovered, and 100% did not fully comply with IOTC Resolution 19/02. The non-compliance observed suggests a widespread disregard for regulations to minimize the negative impacts of dFADs on marine ecosystems. The fact that the dFADs are mainly made of plastic and entangling materials while not being suitably marked—perhaps to intentionally obscure their ownership—emphasizes the need for improved regulation and monitoring. These devices continue to pose significant and long-lasting threats to marine biodiversity50.

Furthermore35,49, note a significant decrease in the prevalence of dFADs with netting in 2021–2022 compared to the past two decades. Our study, based on the analysis of 63 recovered dFADs in Somalia, indicates that only four dFADs had netting, with nets often ranging from 14 m to 33 m long attached to the dFADs. The data analyzed in the study also demonstrates the susceptibility of mangrove and coral reef habitats to beached dFADs. Similarly, a study conducted in the Seychelles found that coral/algae habitats were disproportionately affected by dFAD beaching’s, with 35.3% of events occurring in these areas, indicating a significant impact on these sensitive ecosystems51,52. This is alarming as these habitats are vital for the survival and productivity of various marine species upon which coastal communities depend for nutrition and livelihood support on a daily basis, thus emphasizing the significant social-ecological implications of ALDFG. Furthermore, the finding that certain dFADs may impact multiple habitats indicates the potential for cascading effects on interconnected marine ecosystems.

Based on our calculations and assumptions, we estimate that 1395 ALDFG could have been recovered per year in Somalia’s coastal areas. Similarly, in the Seychelles, clear seasonal patterns in dFAD beaching events were observed, with most occurrences during the monsoon (December–March) and inter-monsoon (April–May), emphasizing the need for targeted prevention, mitigation, and clean-up programs51. Such findings call for strengthened surveillance and international cooperation in the IO to ensure adherence to dFAD fishing protocols and to safeguard marine ecosystems against the extensive dFAD impacts that persist in the meantime.

Our estimates serve as a foundational benchmark for comprehending the magnitude of the issue concerning ALDFG along the Somali coastline. It is imperative to acknowledge that these estimates are predicated on the hypothesis that the incidents of beaching are uniformly distributed across the entire coastline and that the duration of the study is indicative of the typical annual trends. Nevertheless, it is crucial to recognize that these figures are merely estimates. The actual frequency of beaching events might surpass these estimates due to several study limitations. These include the constrained scope of opportunistic recovery areas, the limited personnel allocated for the recovery of FADs, and the shortness of the observation period.

Importantly, our results suggest that substantial numbers of dFADs have illegally entered Somali waters, illegal in the sense that deploying countries did not have legal fishing rights within the Somalia EEZ historically or during the study period. Notably, dFADs are considered to be fishing from the moment of deployment into the water until they are recovered6,8. Their current use could, therefore, be considered IUU fishing if entered into nonauthorized waters8. An additional concern is the lack of data reporting about dFAD numbers and locations being maintained through questionable claims of “commercial confidentiality” coming from the purse seine industry. Recent research elucidates instances of malpractices by purse seine fishing fleets, which have exhibited non-compliance with established maritime boundaries41. Specifically, these fleets have been found to engage in unauthorized fishing operations within the jurisdictional waters of sovereign coastal nations. These identified breaches not only underscore the challenges in maritime governance but also highlight potential infringements on sovereign rights, potential threats to marine biodiversity, and potential destabilization of local fisheries’ economic sustainability. This illegal fishing needs to be addressed as a priority issue, but the IOTC Compliance Committee has yet to react to various submissions across multiple years to their meetings of evidence that non-compliant dFADs are continuing to stand in the waters of its coastal state members.

Our study has identified significant management challenges associated with the use of dFADs, particularly their unauthorized entry into Somalia’s EEZ. Originally deployed in designated fishing areas off the Somali coast, these dFADs frequently drift into Somali waters without formal reporting or authorization and subsequently return to the high seas. This problematic behavior allows fleets to continue fishing around these dFADs—potentially aggregating valuable marine resources—without adequately reporting their movements in and out of the EEZ. Typically, fleets only report when a dFAD is definitively lost, significantly undermining the regulatory frameworks intended to manage the sustainable use of marine resources and combat IUU fishing and overfishing.

Compounding these regulatory challenges is the advancement of technologies on dFADs, such as Artificial Intelligence. For instance, a study conducted by ref. 50 examined data from the 2016/2021 PNA FAD Tracking Program. It reveals that fishing companies have implemented geofencing on a significant portion of dFAD trajectories before transmission to the Parties to the Nauru Agreement (PNA). This practice resulted in notable gaps in the data and introduced potential biases in the analyses conducted, thus affecting the reliability of findings related to FAD usage patterns50. Such clandestine utilization of sophisticated technology presents a formidable obstacle to mitigating IUU fishing, as it allows for the unchecked exploitation of marine resources. Moreover, this conduct not only undermines regional conservation efforts but also threatens the sustainability of the local marine ecosystem. A major barrier to addressing these violations is the maintenance of such data confidentiality on dFAD deployments and the general lack of transparency in the operations of purse seine fleets. This dearth of data impedes regulatory oversight and enforcement, leaving authorities without the essential information needed to confirm compliance or pinpoint infractions.

Addressing these issues necessitates a deeper investigation into how data are collected, shared, and utilized within the industry. It is crucial to explore the reasons behind the lack of transparency and determine which stakeholders benefit from maintaining the obscurity of dFAD data. Improving transparency in fishing operations can be effectively addressed by enforcing more stringent data reporting requirements and establishing clearer accountability mechanisms for non-compliance. Implementing international agreements that mandate the sharing of all dFAD tracking data with RFMO could represent a significant step forward. Additionally, the enhancement of satellite monitoring and other technological measures can ensure that all vessels adhere to the rules set forth by fisheries management authorities50.

Furthermore, according to our findings, 42% of the 56 identified dFADs were from Spanish-flagged vessels. The report highlighted that between the years 2017 and 2018, purse seiners from Spain harvested an approximate total of 330 tonnes of fish from EEZ of Somalia prior to the formal issuance of offshore licenses by the Somali authorities in two decades41. The first license for foreign fishing in Somalia was issued in November 2019. Notably, before this period, the fishing endeavors by the European Union member state, Spain, within Somalia’s EEZ were not conducted under any formal access agreement. This raises pertinent questions regarding marine governance, jurisdictional rights, and the ethics of international fishing operations. This illegal fishing by dFADs within developing coastal States waters is compounded by the potential that dFADs may actually drift back to the high seas with aggregated resources in tow, actually attracting fish outside of Somalia’s waters. IUU fishing poses significant threats to the sustainability of fish stocks, marine ecosystems, and the livelihoods of local fishing communities. This highlights the importance of regional dFAD, ownership, transparency, and data tracking systems along with enforced adherence to the national and international regulations in effectively addressing ALDFG dFADs. It also emphasizes the crucial role of effective traceability mechanisms in determining liability and ensuring compliance with regulations, as well as the important role that regulatory bodies need to play in terms of better enforcement and repercussions for those operating outside of regulations. All factors that were being addressed within IOTC Resolution 23/02, which was politically compromised and objected to following endorsement by two thirds of IOTC members.

The estimated number of ALDFG dFADs in this study represents the best estimate of the number of dFADs that may be present along Somalia’s coast but does not necessarily suggest that all of those have already been stranded. We do contend, however, that the presence of the gear located and retrieved in this study and the estimation calculated do provide evidence that Somalia is a hotspot for illegal fishing by dFADs deployed by industrial-scale foreign fleets. However, it is important to note that our estimates are based on certain assumptions, such as the assumption that the density of recovered dFADs is representative of the entire Somali shelf area. In reality, the density of ALDFG may vary across different areas of the Somali shelf and may change over time due to various factors such as shifting fishing efforts and ocean currents. The analysis presented in this study focused on a specific region within the Somalia EEZ, Mogadishu, and three surrounding landing sites. While this provided valuable insights into the beaching events and compliance of recovered dFADs in this area, it is essential to acknowledge that the study’s scope is not necessarily representative of the entirety of Somalia’s EEZ. The EEZ of Somalia encompasses a vast ocean area, and dFAD beaching events may occur in various locations across the region with less or more frequency than estimated through this study. The study period was also limited to 6 months (including one month of a pilot study), which further affects the representation of beaching events as we do not know if these 6 months are representative of the entire year. Additionally, the opportunistic nature of data collection means that not all beaching events may have been recorded or reported, potentially leading to missing data and incomplete information on dFAD beaching occurrences.

To address these limitations, future studies could consider a more systematic approach to regional data collection, covering a larger geographical area and extending the study duration. The implementation of a standardized regional data collection protocol concerning the retrieval of ALDFG within the jurisdiction of the IOTC would help in capturing a more comprehensive picture of dFAD beaching events in the Somalia EEZ. This, in turn, would provide a more robust foundation for understanding the extent and impact of illegal dFADs, highlighting the importance of transparent dFAD management in the IO. Utilizing advanced tracking technologies and remote sensing methods could also enhance the data collection process, providing a more accurate estimate of the total number of beaching dFADs in the region. Incorporating the proportional number of beaching dFADs in the entire Somalia EEZ would add a significant layer of understanding to the study’s findings, potentially highlighting additional hotspots of illegal dFAD and guiding the development of targeted management measures to address the issue comprehensively. While the current analysis provides valuable insights, it is essential to acknowledge its limitations and the need for further research to encompass the entire Somalia EEZ’s dynamics related to illegal dFAD in country waters.

This research study provides valuable insights into the problem of non-compliant IUU fishing dFADs in the coastal waters of Somalia. It brings to light the extensive prevalence of this issue and reinforces the urgent need for enhanced dFAD management measures, dFAD transparency, and the implementation of a more robust dFAD data tracking system to mitigate the harmful impacts of these devices on the Indian Ocean. It is concerning that our study found not even one of the 63 collected dFADs fully complied with the regulations of IOTC Resolution 19/02. This significant lack of compliance, especially concerning the use of non-biodegradable materials despite Resolution 19/02 only encouraging the flag state to use biodegradable dFADs, underscores the complexity of achieving full implementation of biodegradable dFADs without mandatory enforcement. Such shortfalls in the IOTC regulations have negative ecological repercussions for the entire ocean ecosystem. This highlights the critical need for stringent adherence to international standards and the adoption of enhanced management practices for dFADs, coupled with the enforcement of existing measures. The responsibility for such compliance extends to regulatory authorities, the vessels using dFADs, the fisheries and beneficial owners, as well as flag States.

To enhance compliance with dFAD regulations, stricter monitoring and reporting requirements are essential. The IOTC mandates that any dFAD entering a non-permitted coastal state’s EEZ must be reported within 48 h, facilitating the tracking of unauthorized activities. Enforcement can be achieved through electronic monitoring systems and onboard observers, providing real-time data on dFAD deployments. Additionally, satellite tracking and geofencing detect unauthorized deployments, allowing for prompt regulatory actions. Penalties for non-compliance should be clearly defined, potentially including fines and the classification of vessels as engaging in IUU fishing for violations of coastal state sovereignty. Effective international cooperation among IOTC member states is crucial, involving data sharing and coordinated actions.

dFAD recovery programs are vital for mitigating environmental impacts on marine ecosystems and protecting habitats such as coral reefs and seagrass beds by intercepting and removing FADs before they cause harm. For example, the FAD-watch project reported a 41% reduction in FAD beaching events from 2016 to 2017 due to effective detection and removal strategies, along with the use of non-entangling and biodegradable FAD designs53,54. Transparency and accountability in identifying beneficial owners are paramount for effective dFAD regulation. Implementing these measures can significantly enhance compliance, providing accurate data on dFAD densities and distributions, and contributing to the sustainability of marine resources.

A noteworthy observation from our study is that all these devices were found to have drifted into areas outside of any formal licensing agreements before ultimately being discovered along the shores of Somalia. This movement not only represents a breach of national territorial waters but also undermines Somalia’s conservation efforts and facilitates IUU fishing activities. It is imperative to clarify that these devices had no authorization to operate within the Somali EEZ, which is a critical distinction in addressing the scope of IUU fishing and its repercussions.

However, the recent session of the IOTC in Bangkok in May 2024 marked significant progress in managing dFADs within the region’s tuna fisheries. Two proposals, one submitted by Indonesia, Pakistan, Somalia, and South Africa as co-proponents and the other by the European Union, underwent substantive negotiations with member States. Impressively, the IOTC adopted a framework designed to mitigate the environmental impact of dFADs and ensure sustainable fishing practices. This new framework includes several key measures:

-

Prohibition of the use of fully non-biodegradable drifting dFADs;

-

Gradual phase-out of non-biodegradable components in drifting dFADs to fully biodegradable dFADs in 2030;

-

Reduction of the number of drifting dFADs per vessel (from 300 today to 250 dFADs in 2026 and 225 in 2028)

-

The introduction of dFADs registry to improve governance and ensure compliance with regulations.

Despite these advancements, challenges persist, underscored by the broader socio-economic and political factors influencing fisheries governance. Issues such as sovereignty, the neo-colonial impacts of industrial fishing fleets, and the pervasive IUU nature of dFAD fishing continue to challenge the sovereignty of coastal States in the Indian Ocean, highlighting the persistent effects of neo-colonialism. Although the commission has engaged in constructive discussions, the path toward effective dFAD management remains long and complex. These measures collectively signify a substantial advancement in regulatory oversight within the IOTC’s jurisdiction and reflect a commitment to sustainable fisheries management and the mitigation of environmental impacts associated with dFADs. The successful adoption of these measures, despite complex negotiations and diverse interests, underscores the importance of collaborative international efforts in addressing fisheries management challenges.

Finally, in light of these observations, it becomes imperative for the IOTC and its members to refine and enhance their regulatory and enforcement frameworks continuously. Prioritizing collaborative initiatives that respect and uphold the sovereignty and economic prerogatives of coastal states will be essential in addressing the residual neo-colonial impacts of industrial fishing fleets. As global consciousness regarding the environmental and socio-economic ramifications of industrial fishing intensifies, the IOTC’s dedication to fostering a transparent, participatory, and sustainable governance model will play a critical role in the stewardship of the IO’s marine ecosystems. Effective management of dFADs and the broader challenges of fisheries governance can only be achieved through sustained, inclusive international cooperation, which aligns with both ecological sustainability and socio-economic equity.

Methods

This study analyzes the extent and impact of one type of ALDFG, namely dFADs, on Somalia’s coastal regions, focusing particularly on how these devices contribute to ALDFG. We explore the implications of these dFADs for IUU fishing and marine ecosystem health. Our study assesses the impact of dFADs on marine ecosystems with an emphasis on their contribution to IUU fishing within the Somali EEZ. Although our data collection does not directly document technological tracking and monitoring, our analysis acknowledges the role these technologies play in complicating fisheries management. We focus on the recovery and documentation of ALDFG dFADs, analyzing their presence, distribution, and compliance issues as indicators of potential IUU activities which none of these dFADs register in the Somalia EEZ. This approach allows us to infer the broader implications of dFAD technology on regulatory challenges and IUU risks in the Indian Ocean. The research centers on four Somali beach sites: Jazeera, Liido, Warsheik, and Adale (Fig. 5). These sites fall between 2.0070° N, 45.2841° E, and 2.758889° N, 46.328611° E with an overall distance of 160 km from Jazeera beach to Adale, which covers ~6.90% of Somalia’s coastline or 0.459% of inshore fishing area. Conducted in two stages, an initial pilot in March 2022 was used to refine data collection methods, followed by a main study period from August to December 2022. Data were then organized and assessed electronically. These particular beach sites were selected due to reports from local fishermen and community heads about dFAD beaching incidents. Notably, three of these sites are vital nesting grounds for turtles and are home to crucial mangrove ecosystems.

The map highlights the four primary locations along the Somali coast where drifting Fish Aggregating Devices (dFADs) have been recovered: Jazeera, Liido, Warsheik, and Adale. The red markers indicate these specific recovery sites. This research focuses on the recovery and documentation of Abandoned, Lost, and Discarded Fishing Gears (ALDFG) dFADs, analyzing their presence, distribution, and compliance issues as indicators of potential Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) fishing activities. None of these dFADs are registered in the Somalia EEZ. This approach allows us to infer the broader implications of dFAD technology on regulatory challenges and IUU risks in the Indian Ocean. ©Google Maps. This image is being used for illustrative purposes under the terms of Google Maps’ standard permissions, which allow for such uses without the need for direct permission from Google.

The data collection process was divided into two phases: the pilot study and the main study. Data collection during the pilot study was conducted in an ad-hoc manner, where data were collected when dFADs were removed from where they had beached or stranded. The retrieved dFADs collected during this period were stored locally for later assessment. This phase of the study was conducted during March 2022. The main study was then conducted from August to December 2022 using a standardized protocol for data collection (Supplementary Fig. 1), which included photographs and descriptions of the dFAD. Fishers and community members were provided with a translated version of the data collection form to facilitate their understanding and implementation of the collection procedure (Supplementary Table 1). The project required fishers and local communities to report and recover ALDFG in the Somali waters or the coastal zones on the four beach sites.

The data collection form consisted of three main sections:

-

1.

Location/environment recovered: Information on the location and environment where the dFAD was recovered, such as the latitude and longitude, beach site name, and habitat type.

-

2.

FAD structure and design: Information on the dFAD structure and design, such as the type of dFAD, the materials used, the satellite buoy, raft cover, and sub-structural equipment.

-

3.

Observed entanglement events: Information on any observed entanglement events, such as the number of fish, type, size, and habitat entanglement.

The data were collected using the above protocol, and photographs were taken of all material of the recovered dFADs (the raft covers, satellite buoys, ropes, and all sub-structural equipment) and compiled through electronic versions for analysis.

Collected data were managed using electronic databases, with details stored in an Excel file. Images of the recovered ALDFG were analyzed following IOTC Resolution 19/02 requirements as the guide for compliance. Descriptive statistics were applied to the data to summarize the number of recovered dFADs, their materials, entanglement events, compliance, and geographic locations.

To understand the scale of dFAD strandings in Somalia, we estimated the prevalence of ALDFG in both space and time using the total number of recovered dFADs and the recovery area as our key parameters before scaling up the equation to cover the entire Somali shelf, assuming consistent density throughout and extrapolating this out to estimate the annual impact. Geospatial techniques were used to visualize the spatial distribution of the dFADs. Geospatial techniques were used to visualize the spatial distribution of the dFADs. Statistical methods were used to examine patterns in dFAD recovery rates and compliance with international fishing regulations, helping to highlight areas with high incidences of ALDFG and potential IUU fishing hotspots.

To understand the levels of compliance in the sample, they were assessed using 4 indicators of compliance based on IOTC Resolution 19/02 requirements as the guide:

-

dFAD rafts must not include any meshed materials;

-

dFAD aggregators must not include any meshed materials;

-

dFAD buoys must be marked with the manufacturer’s serial number; and

-

dFAD buoys must be marked with the vessel’s Unique Vessel Identifier (UVI) number from the IOTC.

Each dFAD recovered was measured against these metrics to assess how many were fully compliant with IOTC Resolution 19/02.

An examination of the entanglement events was conducted to assess the potential environmental impact of dFADs. Content analysis was applied to categorize and code the entanglement data, identifying marine habitats/species affected and the frequency of such events. The study’s methodology aimed to give an in-depth analysis of the effect of ALDFG on the marine ecosystem, emphasizing their prevalence in the Somalia EEZ.

To estimate the prevalence of lost, abandoned, and discarded dFADs in Somalia’s coastal areas, we used the total number of recovered dFADs and the recovery area as our key parameters. Specifically, we obtained data on the total number of recovered dFADs, and the recovery area rate of dFADs, we first determined the total number of dFADs successfully recovered during the project. We then divided this total by the duration of the project. This process enabled us to derive the average number of dFADs recovered per day. Similarly, we were able to determine the average number of dFADs recovered by area by dividing by the total study area.

-

Number of recovered dFADs in study area (({N}_{r})): to be determined.

-

Length of study area coastline (({L}_{s})): 150 km

-

Duration of study (({P}_{{dy}})): 160 days

-

Total length of Somali coastline (({L}_{t})): 3333 km

-

Total area of Somali shelf (({A}_{t})): 737,289 km2

-

Area of the study shelf (({A}_{s})): 2289 km2 (*Derived from Somalia Shelf Area: 50,878 km2)

Calculation process

We calculated the recovery rate per day

We Calculated the Density of Recovered dFADs per km of Coastline in the Study Area (({D}_{k}))

We Calculated Density Proportion for the Study Area (({P}_{{dens}}))

We also calculated Proportional Density for the Entire Somali Shelf Area (({D}_{{prop}}))

We estimate the total number of Recovered dFADs of entire Somalia EEZ (({N}_{{total}}))

Responses