Dual orexin receptor antagonists as promising therapeutics for Alzheimer’s disease

Introduction

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a devastating proteinopathy affecting millions of people1. With no known cure, it is imperative to develop effective treatments targeting a variety of pathological processes and symptoms associated with AD, including sleep disorders. It is known that AD is characterized by the accumulation of both tau and amyloid beta (Aβ) aggregates2. These aggregates are thought to be key factors contributing to neurodegeneration and impaired cognition in AD3. Furthermore, AD pathophysiology, sleep and cognitive impairments may be intertwined. For example, increased tau and Aβ aggregation (TAβA) in the hippocampus may lead to impaired hippocampal-cortical interactions during sleep, and is associated with impaired memory formation and consolidation4,5. The population with AD is growing, and thus the development of effective treatments is critical for patients, caregivers and society6,7. New drugs such as lecanemab recently have been introduced into the clinic, but these and most other pipeline efforts have focused on directly targeting the TAβA observed in AD8,9. This family of medications is limited by their risk of amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA) that present as ARIA-E (characterized by edema or effusion) or ARIA-H (characterized by microhemorrhage), which are seen via magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the brains of AD patients10. While such drugs may begin to slow progressive loss of memory and cognitive function, AD also carries many serious comorbidities such as sleep disruption and neurovascular diseases11,12,13. Additionally, other pathological features may be contributing to AD pathogenesis, including inflammation, sleep disorders and psychiatric risk factors, such as history of depression14. Sleep disruption is a risk factor for AD and has a bidirectional relationship with AD14,15,16,17. From a clinical perspective, assessment and management of sleep disruption in patients with AD should be among the most impactful interventions for both patients and their caregivers, as sleep disruption creates a significant burden for both18. There is also growing evidence suggesting that sleep disorders are a major contributing factor to AD pathogenesis by compromising the macroscopic waste clearance system for the brain known as the glymphatic system19. This system uses glial shunting into a lymphatic vessel network to clear waste from the central nervous system, and this activity is thought to be facilitated by sleep19. More directly relevant to AD, amyloid and tau aggregates are reduced during sleep and increased during awake periods in rodents and humans, suggesting that either sleep increases clearance of TAβA via the glymphatic system (or other mechanism), or such aggregation may increase during wake periods, or both15,16,17. Consistent with an increased production mechanism, sleep disruption in humans has been shown to lead to increased Aβ production17.

Numerous studies have associated sleep disorders with AD, thus it is imperative to delineate a mechanism for the linkage between TAβA, sleep and AD18. Research has shown that during slow wave sleep (SWS), glymphatic flux is heightened, thereby increasing the clearance of excess metabolites from the brain19 and suggesting that the reduction in amyloid observed in rodents during sleep15 may be due to this glymphatic mechanism. However, a recent study called this hypothesis into question by suggesting that the heightened glymphatic clearance during sleep, previously reported by several labs20, may have been driven largely by a methodological artifact and, in fact, that glymphatic flow may be lowest during sleep21. Thus, the precise mechanism driving the relationship between sleep and reduced AD pathogenesis is presently less clear15. This gap in knowledge highlights at least two critical areas that warrant future studies to develop novel treatments for AD. First, can sleep be facilitated to reduce amyloid aggregation and potentially other pathophysiological processes, such as inflammation, associated with AD? The orexin pathway has been established as an important regulator of wake/sleep cycles, and drugs antagonizing this pathway, like dual orexin receptor antagonists (DORAs), e.g. suvorexant, are effective for treating insomnia22. Thus, it is plausible that treating AD patients with a DORA, especially those with impaired sleep, may slow AD pathology by improving clearance of protein aggregates and other wastes. Because the orexin system is highly specific for sleep/wake regulation, DORAs may be preferred for their hypnotic efficacy with fewer side effects compared to current mainstay hypnotics, such as insomnia drugs that promote GABA systems23. Second, can the mechanism underlying reduced TAβA during sleep be elucidated to resolve the current controversy regarding the glymphatic mechanism or generate evidence for an alternative mechanism?

Previous Reviews and Critical Gaps

Recent reviews have covered some of the factors that may underlie the relationship between sleep and AD pathophysiology. For example, others have reviewed diurnal fluctuations in amyloid15, the evidence that the glymphatic system plays a role in AD pathology24, and that a key mediator of waste clearance through the glymphatic system is the water channel aquaporin-4 (APQ4), which co-localizes with astrocytes25. There also have been several reviews exploring the connections between sleep disorders, the glymphatic system and AD. These reviews explored potential links between increased protein aggregation and toxicity, and sleep and circadian dysregulation in AD26. Uddin et al. reviewed evidence for a causal relationship between AD and circadian dysfunction27. For example, higher levels of TAβA are linked to poor sleep quality, while conversely, short sleep duration is associated with increased Aβ burden, again supporting a bidirectional relationship between AD and sleep. Ahmad et al. reviewed evidence of correlations between the glymphatic system and aspects of circadian dysfunction, but only delved slightly into therapeutic agents such as suvorexant (a DORA drug), trazodone and Melatonin28.

Based on the current understanding of how sleep can be modulated by available sleep-enhancing drugs, sleep disruption, including fragmentation and irregularity in AD, is a modifiable risk factor for progression to AD and a treatable symptom that can slow or halt progression of the disease. While topics related to the glymphatic system, orexin system and circadian dysfunction in relation to AD have been reviewed individually, therapeutics such as DORA sleep drugs and the relationship with a potential glymphatic mechanism for the clearance of amyloid and tau is essentially untouched as a comprehensive review topic. The only exception is a mini-review by Zhou and Tang on the topic of sleep/wakefulness and effectiveness of DORA treatments in AD29. However, this review aims to be the first to focus on thoroughly synthesizing available research findings regarding DORA drugs as a therapeutic for mitigating insomnia and disease progression for AD and providing a timely review of the relationship with glymphatic clearance and its monitoring in the context of a recent report challenging current theory.

Bidirectional Relationship Between Sleep Disruption and AD

Some studies in humans have found evidence that disrupted sleep can be a primary cause of AD by contributing to an increase of Aβ levels, as seen after sleep deprivation17,30. Other studies suggest that AD pathophysiology is causing sleep disruption26. For Amyloid Precursor Protein/Presenilin 1 (APP/PS1) mice, it has been reported that amyloid plaques form and subsequently disrupt sleep. However, it should be noted that the plaques were not reported in the parts of the brain thought to be critical for control of sleep and wake cycles, such as the hypothalamus14,20,31. Similarly, in APP/PS1 mice, the sleep-wake cycle markedly deteriorated, and diurnal fluctuation of interstitial fluid Aβ dissipated following plaque formation. Clearing amyloid restored sleep and diurnal fluctuations in interstitial fluid Aβ, suggesting that plaque formation may lead to impaired clearance during sleep, further exacerbating amyloid aggregation32. Tau in brain interstitial fluid is shown to be increased in the P301S mouse model during both wakefulness and with sleep deprivation, suggesting a similar relationship between sleep and tau aggregation as has been described for Aβ33. Similar to mice with PS1 mutations, young adult humans with PS1 mutations also showed a marked reduction in the diurnal fluctuation of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) Aβ following Aβ plaque formation, as assessed via PET scans and serial CSF samples, suggesting impaired clearance during sleep in humans following Aβ aggregation32. These findings provide evidence that both central circadian rhythms and diurnal fluctuation of CSF are influenced by Aβ plaque formation. It is possible that dampening of these fluctuations represents decreased clearance via the glymphatic system. Together, these results suggest that, regardless of which comes first, a vicious cycle may result, with sleep disturbances further exacerbating AD pathophysiology and AD pathophysiology, in turn, reaching a tipping point where clearance of tau and amyloid aggregates during sleep is reduced.

Disrupted Sleep May Lead to Glymphatic Dysfunction in AD

The glymphatic system is thought to play an important role in transporting nutrients and signaling molecules into the brain parenchyma while clearing toxic interstitial chemicals and proteins out of the brain23. This system seems to be most effective during sleep, especially during non-rapid eye movement (NREM), and is therefore reliant on a healthy sleep-wake cycle24. The role of the glymphatic system in AD is crucial, as it is thought to be the main source of clearance for AD pathologies such as TAβA through the APQ4 channel24. APQ4 is a protein expressed by glial cells called astrocytes34, and is critical for allowing bidirectional water flow to and from the CNS24. APQ4 channels have been implicated in clearance impairments35,36 as is observed with AQP4 channelopathies [autoimmune disorders where one’s immune system targets the AQP4 channel37]. In fact, loss of APQ4 water channels sharply increased both Aβ plaque formation and cognitive deficits in APP/PS1 mice23. There is also a notable age-related decline in APQ4 polarization, which could lead to a static reduction in glymphatic function and favor AD pathological accumulation, potentially hastening disease progression37. Furthermore, the glymphatic pathway also is regulated by the circadian system as APQ4 is regulated by the circadian clock [internal clock with an approximately 24 h rhythm that is typically entrained to the light/dark cycle19,38. Additionally, it was recently shown that pharmacological enhancement of slow-wave activity shows a reduction in amyloid pathology along with cognitive improvement in early disease stage Tg2576 mice providing evidence that slow wave activity plays a role in glymphatic clearance of AD pathology39. Alongside this finding, is has also been discovered that restoration of disrupted slow wave oscillations via optogenetics can health amyloid deposition in APP mice, indicating the important relationship between slow wave activity and AD40. Finally, while the glymphatic system has been the main source of attention (and we are guilty of contributing to this focus in our review), it should be acknowledged that the meningeal lymphatic system is also thought to clear waste during sleep41,42,43, and dysfunction in this system has also been associated with neurodegenerative disease42,43,44. This additional promising target also deserves additional research attention.

While direct evidence linking glymphatic dysfunction to reduced clearance in humans is lacking, there is some indirect evidence. In humans, the efflux of CSF containing Aβ and phosphorylated tau is reduced in patients with AD compared with age-matched controls45. The suppression of CSF clearance in AD is so substantial that it may serve as a biomarker for the disease23. It also was discovered that the amount of interstitial fluid Aβ positively correlated with wakefulness and significantly increased during acute sleep deprivation46. Recent work has suggested that it may be possible to more directly measure peri-vascular glymphatic flow and associate it with sleep and neurodegenerative disease47. Thus, there is considerable evidence that amyloid and tau aggregates decrease during sleep and that components of the glymphatic system are linked to this sleep-induced reduction of these aggregates in rodent models of AD and similar dysfunction is also apparent in humans with or progressing towards AD.

Is Glymphatic Flow Greatest During Sleep?

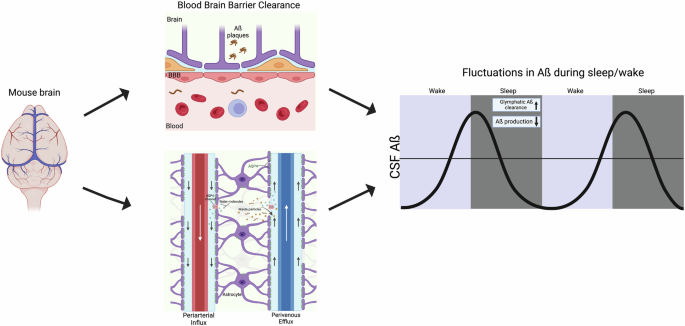

Surprisingly, a recent article has suggested otherwise, indicating that clearance is reduced during sleep (compared to wake) rather than increased21. Until this study, it was unclear whether sleep enhances clearance via increased bulk flow (i.e., inflow and outflow) as most studies measured inflow and only assumed outflow. Therefore, this study investigated outflow by injecting a small-molecule dye into the caudate putamen and tracking its movement into the cortex. The authors found that the movement is predominantly caused by diffusion and remains unchanged during sleep. Furthermore, EEG data show a negative correlation between delta power and peak clearance, indicating that the deeper the mice slept, the lower the clearance. This finding raises the possibility that clearance during sleep occurs through a non-glymphatic mechanism. For example, clearance may be supported by other systems, including the blood-brain barrier (BBB), as sleep was also found to promote endocytosis and clearance of metabolites across the BBB [Fig. 148]. However, this study did not actually test clearance but measured the flow of fluorescent tracers within the brain, making it difficult to draw firm conclusions about clearance from these results. Moreover, this study does not explain the literature linking the APQ4 channel to clearance during sleep. Additionally, APQ4 channel deletion does not alter BBB clearance, making the BBB an unlikely alternative mechanism49. It also should be noted that the study showing reduced glymphatic flow during sleep examines normal mice and only used male mice, while AD research has focused on female mice because pathology and cognitive impairments tend to be greater in both female mice and humans, though not necessarily due to the same underlying causes21. Furthermore, this new study does not offer an alternative explanation for why the opposite pattern is observed in mice modeling amyloid and tau aggregation (decreased amyloid during sleep and increased amyloid during wake). Finally, related to this point, Miao et al. selected a small dye that could move freely in extracellular spaces; however, larger molecules (such as Aβ oligomers and plaques and tau tangles) may behave differently. Therefore, while this study’s provocative data suggests more work is needed to understand the relationship between glymphatic flow, amyloid/tau aggregation and sleep, it appears that the paper alone is insufficient to change current views about glymphatic waste clearance and AD. Furthermore, a recent article has provided further context as to the mechanism underlying glymphatic clearance during sleep50. Their findings attribute an infraslow rhythm that occurs during microarousals and is accompanied with a surge of norepinephrine, which controls opposing changes in blood and CSF volumes, predicting glymphatic clearance. This recent finding suggests that there are other factors contributing to glymphatic clearance, specifically during sleep, which is contradictory to the above conclusion from Miao et al.50.

The mechanism that facilitates these fluctuations may be through blood-brain barrier (BBB) clearance or glymphatic clearance, both of which contribute to clearance during sleep. Understanding the mechanisms that aid in reducing amyloid beta levels during sleep is important for understanding Alzheimer’s disease (AD) pathology. Note, the recent finding that glymphatic flow may be lower during sleep does not account for the Aquaphorin-4 APQ4 literature, and APQ4 deletion does not impact BBB clearance. Therefore, it remains that the mechanism of amyloid clearance during sleep is likely at least partially mediated by the glymphatic system (see text for details). This figure was generated using BioRender.

Assessment of Glymphatic Function

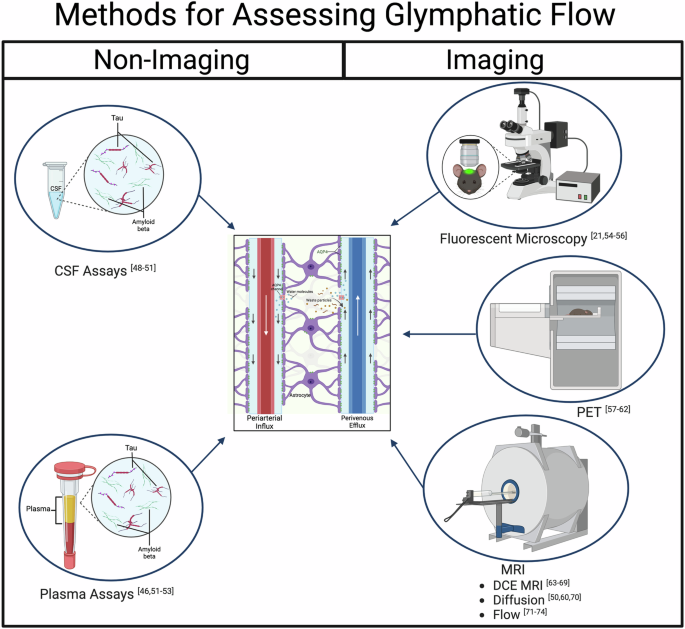

One concern highlighted by the recent negative finding suggesting that glymphatic flow may not be increased during sleep is that there still does not exist a gold standard for assessing glymphatic flow. In fact, Miao et al. did not use a new method, but rather an old method in a new way. Therefore, a discussion of currently available methods and their relative advantages and disadvantages is warranted before reviewing the relationship between sleep and reductions in pathophysiological features of AD. Assessment of glymphatic system function may be achieved through several methods, including non-imaging and imaging techniques. Currently, as there is no consensus on the best imaging method to assess different aspects of glymphatic clearance, this section reviews the most popular and promising techniques.

Non-Imaging

Biological waste exits the brain via the CSF, ultimately clearing the brain though bloodborne transport. Indirect glymphatic clearance assessment is possible with blood or CSF biomarkers, with the latter collected via lumbar puncture. CSF biomarkers are very sensitive and low cost, but due to the invasive collection method, are not always practical clinically51. A strong correlation exists between the magnitude of slow-wave sleep disruption and levels of Aβ40 in the CSF, while poor sleep quality over several days was linked to increased CSF tau52. However, note that the 42 amino acid variant of Aβ is thought to be the stronger driver of amyloid aggregation. AD patients have significantly lower levels of Aβ, total tau and phosphorylated tau in CSF when compared to cognitively healthy control patients (presumably due to less clearance). Similarly, individuals with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and lower perivascular diffusion also had significantly lower levels only of Aβ in CSF44. Even in cognitively normal amyloid-negative participants, multiple forms of Aβ and tau concentrations in CSF were found to increase by approximately 35–55% during sleep deprivation, while plasma concentrations decreased by 5–15%, indicating that protein clearance from CSF to plasma was impaired by sleep loss53. By correlating with possible plasma biomarker concentrations, waste products that are thought to be cleared via glymphatic mechanisms, such as Aβ, tau, neurofilament light chain and glial fibrillary acidic protein, can be assessed54. However, such an approach cannot distinguish clearance via the BBB, which also occurs during sleep48,55. However, these findings imply that there is a progressive reduction in clearance, and consequently, higher residual waste products in the MCI brain and (to a greater potential extent) in the AD brain, and that there exists a potential inverse relationship between protein transport and sleep deprivation.

Imaging

Fluorescence

The glymphatic system was, in part, discovered using fluorescence microscopy. Through the use of fluorescent tracers injected into the cerebral cortex of mice, CSF was labeled, and its dynamics and flow were mapped with two-photon scanning microscopy56. Fluorescent specificity is high, allowing for precise/direct viewing of bulk CSF influx along para-arterial pathways. Importantly, the ability of the tracer to enter the interstitial spaces from the paravascular sheaths was dependent on its size. This discovery becomes particularly relevant for future imaging studies. However, due to the limited field of view/depth, deeper regions of the brain could not be imaged via two-photon methodology. Influx pathways were verified, and efflux pathways were determined separately via ex vivo methods. Note, this is an important limitation as highlighted by the recent negative result paper21 which suggests that an overreliance on measures of influx could be a problem. Tracers moved inward along arteries and proceeded to accumulate along paravenous routes during exit, particularly along the medial internal cerebral and caudal rhinal veins56. Another study utilized two-photon imaging to study glymphatic flow in different arousal states of mice57. It was discovered that anesthetized and sleeping mice have similar influx rates of CSF along periarterial spaces and into the parenchyma, but mice that are awake have significantly reduced influx. However, the recent study measuring efflux during sleep and anesthesia calls this result into question21. Furthermore, measures that require anesthesia should be interpreted with caution because there are differences in glymphatic clearance between mice in sleep and anesthetized states55. While fluorescent microscopy provides excellent resolution over small areas (made accessible with an intracranial window), alternative imaging modalities are needed to assess deeper brain structures.

PET

Positron Emission Tomography (PET) utilizes positron-labeled radiotracers to gather images. Although limited with respect to resolution, PET is beneficial due to its high sensitivity and selectivity to concentration58. Quantified PET also reduces assumptions and estimations of tracer mass concentrations. Numerous PET agents are available, including the conventional fluoro-deoxy-glucose (18FDG), larger-sized fluoro-deoxy-sorbitol (18FDS) and 11C-Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) that targets amyloid beta. To study pharmacokinetics of the glymphatic system in rats, a recent study used 18FDG injected intravenously as a baseline versus injection into the cisterna magna58. Obtained at 5-min intervals over 1.5 h, scans demonstrated that the uptake of 18FDG was different between the two injection locations. CSF administration displayed an earlier time to peak plateau (25 min) in the brain compared to intravenous injection (35 min). Furthermore, this study provided evidence that both uptake of 18FDG into the CSF and brain as well as clearance from the brain (increase and then decrease in signal) could be monitored temporally, which is relevant to both entrance and exit from the glymphatic system as well as more complex modeling of the kinetics of glymphatic clearance. As a larger tracer and analogous to similar work using fluorescent agents of different sizes, 18FDS has the potential for quantitative assessment of different aspects of glymphatic system clearance over time59.

The Pittsburgh compound is often used to evaluate Aβ accumulation in AD, due to its specificity for extracellular Aβ [58]. A study utilized this compound’s specificity to evaluate build-up in relation to potential glymphatic clearance60. Patients with MCI, AD, and normal cognition were injected intravenously with PiB and scanned continuously for 70 min. A strong correlation between PiB accumulation and the DTI-APLS score, a metric that will be explained in the MRI section below, suggests that glymphatic drainage is closely related to initial Aβ deposition60. A separate study using a tau radiolabel (18F-THK5117) to assess ventricular CSF time-activity found that CSF clearance from the ventricles in AD patients was reduced by 23% compared to the cognitively normal over the course of 90 min of continuous PET scanning. Furthermore, the PiB Aβ burden was related inversely to 18F-THK5117 CSF clearance, suggesting glymphatic system impairment in AD patients45. Additional support for these findings comes from a PiB study looking at ventricles and tissue clearance in MCI and AD patients61. Lateral ventricles had lower PiB signal in AD than control patients. Furthermore, AD patients had higher PiB signal in gray matter, implying that CSF-mediated tissue clearance is decreased. CSF tissue clearance may be related to Aβ deposition before AD onset, as evidenced by MCI patients displaying PiB values between those of control and AD groups. Dynamic PET scans are a viable option for monitoring glymphatic system dynamics and changes with pathology61. One pitfall of PiB is that its half-life is roughly 20 min62, limiting its use to shorter periods of time or continuous injection.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Due to its noninvasive nature and accessibility both in research and clinically, focus within the imaging field is currently on developing and refining MRI methods to evaluate the glymphatic system. MRI can utilize a wide range of techniques to create diverse types of images, providing various avenues for the assessment of glymphatic function. The most popular are dynamic contrast enhancement, water diffusion and flow-based imaging.

Dynamic Contrast Enhanced (DCE)

DCE-MRI utilizes exogenous agents to provide contrast, which allows for tracking of flow within the glymphatic system. Among potential agents, gadolinium-based contrast agents (GBCA) are popular as they provide T1-relaxation-related signal enhancement with reduced acquisition times. Because they require a chelating cage molecule to sequester the otherwise toxic Gd from biological processes, GBCA sizes can be tuned in a similar fashion to fluorescent probes, giving differential access to the glymphatic system56. For example, gadopentetate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA) at 938-Da molecular weight has been injected into the cisterna magna of rats to study glymphatic transport changes with age dynamically with repeated imaging to capture influx and efflux within the brain63. This study identified a widespread reduction in influx and efflux in aged animals compared to young animals, along with morphological changes within the brain. Similarly, Gd-DTPA was used to track CSF flow in a murine model of AD tau pathology, rTg4510, showing that glymphatic influx was lower in areas of tau deposition64. Another GBCA injected intrathecally, Gadospin at 200 kDa accumulated in perivascular spaces as it could not exit through the astrocytic end-feet gaps, compared to Gd-DTPA that was able not only to enter perivascular spaces, but continued along the full pathway of glymphatic flow and was found throughout the parenchyma56, Gadobutrol has been found to penetrate the parenchyma deeply and into all subregions of the human brain65. At 550-Da, gadobutrol is even smaller than other GBCA, which allows for full glymphatic transport throughout the brain66,67. These studies helped confirm the existence of the glymphatic system in humans, as previously reported in rodents, and demonstrate the importance of agent size and access with respect to the penetration and evaluation of the glymphatic system and its dynamics.

Another comparison study of tracers within the glymphatic system was performed using Gd-DTPA and 17O labeled water68. Previous work had established the importance of AQP4, a protein intrinsic to water transport channels, on interstitial fluid movement in the brain through the use of H217O MRI69. The study hypothesized that, because specific AQP4 channels exist within the brain, previous estimations of glymphatic flow were likely underestimated due to limitations in the transport of the larger Gd-DTPA. These agents were injected via the cisterna magna into rats. H217O-induced relaxation displayed more rapid glymphatic flow and more extensive penetration into the parenchyma than the Gd-DTPA, supporting the hypothesis69. As such, H217O proved a good tracer for glymphatic flow evaluation, but it is important to note that the low natural abundance and cost of isotopically labeling make 17O a difficult and expensive option as an indirect contrast agent69.

Diffusion

Unlike exogenous contrast agents, diffusion-based MRI utilizes endogenous water to map the local environment with respect to translational movement, bulk flow and restrictions. Though typically applied to probe microstructural aspects of ordered white matter tracts or exchange in the more anisotropic gray matter, the sensitivity of diffusion MRI to fluid motion can interrogate the perivascular channels of the brain as well as links between vascular pulsation and CSF movement70.

Utilizing a diffusion encoding formalism and ultra-long echo time to eliminate tissue signal contributions and focus only on CSF and perivascular flow, motion probing gradients applied parallel or orthogonal to perivascular spaces were sensitive to flow directionality. This approach demonstrated parallel flow to known structures (i.e., right and left perivascular tracts off the Circle of Willis) but also significant dependence on the cardiovascular cycle, changing by 300% during moments of arterial pulsation. This study established modified diffusion MRI to interrogate the relative magnitude and directionality of perivascular flow noninvasively.

Making use of the 3D nature of imaging gradients to probe arbitrary directions, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) investigates the anisotropy of water diffusion within the restricted and tortuous microenvironment of the brain. With respect to glymphatic clearance, a DTI-based method has been proposed to evaluate DTI along the perivascular space (DTI-ALPS) running parallel to deep medullary veins. Although limited in its application to cerebral white matter level at the upper part of the lateral ventricles where medullary veins run transversally to and parallel with the image slice orientation, DTI-ALPS is proposed to provide a noninvasive index that is decreased significantly in AD patients compared to controls and positively correlates between the DTI-ALPS indices and measured CSF Aβ44. Another study determined that the DTI-APLS index had a strong correlation to the amount of Aβ deposition in AD patients, as quantified by PET60. Researchers discovered a significant association between the ALPS index of AD and cognitively normal patients with gray matter volume loss64. Although a growing body of literature has applied the analysis to multiple pathologies that may impact glymphatic clearance, DTI-ALPS is considered controversial due to the potential for interference from white matter tracts and blood vessels and its inability to quantify whole brain glymphatic clearance beyond the deep medullary veins.

Flow

Arterial spin labeling (ASL) is an endogenous contrast imaging method that is typically used to quantify larger artery flow as well as capillary-level perfusion. Using an ultra-long echo time in the ASL sequence allows for tissue signal to be eliminated, allowing long spin-spin relaxation CSF to be emphasized71. This approach showed that water delivery across the blood-CSF barrier in the 3xTg-AD mouse model of TAβA is increased more than 50%, with high rates detected in the AD mouse at early stages, even before widespread tau depositions. This modified ASL method may be able to detect early changes both in choroid plexus output as well as glymphatic flow/clearance in AD transgenic models.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which exploits cognitive activity coupled to micro-hemodynamics, also has an intrinsic flow basis that recently has been applied to measure glymphatic clearance. One study utilized resting state (rs)-fMRI to quantify CSF velocity in humans via an inflow effect67, in which signal intensity increases as unperturbed CSF (with respect to RF saturation) moves into the imaging voxel. The degree of signal intensity change is related to the rate of flow/velocity. Ventricular CSF velocity was determined to be within the range of values found through other MR methods, validating the methodology. Although only able to determine velocities perpendicular to the imaging slice, the benefit of this method is its ability to capture slow flow velocities, with which many other methods struggle. This methodology could be applied to study even oscillating CSF flow, potentially monitoring changes that may indicate glymphatic alterations relating to AD pathology67.

Another study sought to determine the direction of CSF flow, as well as to elucidate the coupling of hemodynamics with CSF flow through rs-fMRI72. Influx and efflux were studied using different directionalities of the imaging scans. Influx scans were acquired from neck to top of the head, and efflux scans vice versa. Fourth ventricle and superior brain CSF movement was found to be bi-directional. Additionally, there was coupling between CSF flow fluctuations and hemodynamics of the brain of awake patients.

Another type of fMRI relies on the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal to analyze brain activity. A study compared rs-fMRI global BOLD (gBOLD) to evaluate whole brain signals as well as CSF movement, measured via the inflow effect73 as discussed above. Significant coupling was found between ventricular CSF movement and changes in the gray matter gBOLD signal, with decreased coupling only apparent in neurodegenerative (Parkinsonian) cases with identified cognitive deficits. These findings indicate that gBOLD-CSF coupling acquired with the same rs-fMRI scan may provide metrics for quantifying cognitive decline in neurodegenerative diseases, but also hint at the disruption in flow dynamics that may be related to glymphatic dysfunction73.

In summary, MRI methods leverage both exogenous and endogenous approaches that can interrogate the inflow and outflow of the glymphatic system, as well as CSF production and movement (also see Fig. 2). With tunability over a range of differentially sized contrast agents down to the magnetic labeling of water, MRI can probe different compartments of the CSF and glymphatic systems, offering the potential to address concerns raised by Miao et al. about a general lack of measures of glymphatic outflow or at least an overreliance on measures on inflow21. MRI studies can be designed, pursued and compared under both awake and anesthetized conditions to assess impacts to glymphatic in- and outflow under these conditions. In both preclinical animals and translation to clinical patients, ASL and rs-fMRI have the unique potential to assess in- and outflow from the whole CSF and glymphatic systems endogenously, with the potential of diffusion-based approaches to provide complementary though potentially localized flow-related metrics. In addition, a critical complement to these MRI approaches would be to assess glymphatic clearance for comparison between the anesthetized and sleeping state versus the awake condition, which is possible in animal models. Such experiments would set baseline conditions to assess the impact of DORAs on facilitating glymphatic flow and clearance of amyloid, tau and other pathophysiology in rodents modeling aspects of AD and humans at risk for AD, which likewise can be investigated with MRI approaches.

Non-imaging methods to evaluate glymphatic flow include CSF and plasma assays, which provide direct concentration measurements of the products of interest but are invasive. The imaging methods utilize various contrast agents and tracers, which can be tuned by size to interrogate different aspects of the glymphatic system. Fluorescence microscopy was able to define the glymphatic system initially and has high resolution and specificity; however, it has a limited field of view and cannot probe deep into the brain. PET can provide dynamic information, is highly sensitive and selective, but has limited resolution. MRI can use endogenous contrast in addition to exogenous agents, making it less invasive and provides a wider range of imaging capabilities, while also being highly translatable to clinical work. This figure was generated using BioRender.

Orexin System in the Sleep-Wake Cycle and Interactions with AD

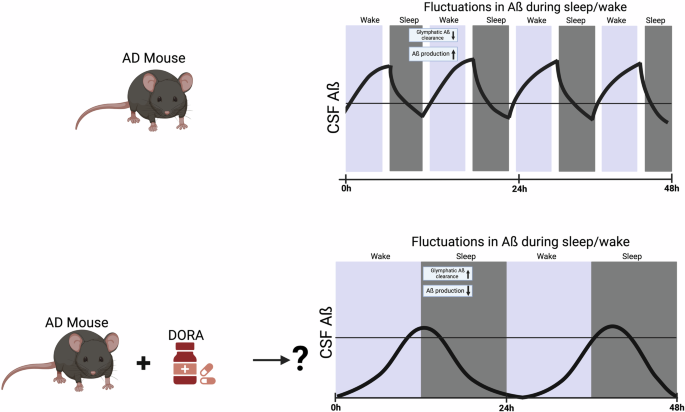

Regardless of the outcome of the recent challenge to the theory that glymphatic flow is increased in sleep (which alone is not sufficient to shift current theory), if these challenges eventually lead to significant revision of this theory the potential for DORAs to treat such dysfunction remains. In other words, given the preponderance of evidence that sleep leads to reductions in amyloid and tau aggregates, thus, facilitating sleep should reduce pathology regardless of the precise mechanism. Further, it has been reported that the orexin system is compromised in neurodegenerative diseases. However, it has not been determined whether the dysregulated orexin system contributes to the pathology of neurodegenerative diseases or is secondary to the disease process74,75. The orexin system is involved in a variety of functions across the body, such as mood, cognition, feeding behavior and sleep74. Orexin A and orexin B are neuropeptides that are strong regulators of the sleep-wake cycle76. Sleep is regulated by two distinct but interconnected mechanisms: sleep homeostasis (the pressure that builds to sleep as the time without sleep increases) and the circadian clock77,78,79. Optimal sleep quality requires alignment of these two sleep-regulating pathways, and disruptions in either one can affect the other pathway and lead to sleep disorders80,81. The homeostatic mechanism is mainly responsible for the total amount of sleep and sleep depth, while the circadian clock regulates the timing of sleep onset and consolidation of sleep. The circadian clock in the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) is considered a master clock that drives daily rhythms in behavior and physiology82,83,84, and dysfunction of the clock has been implicated in diverse disease states including sleep disorders85,86,87,88,89. The homeostatic pathway is driven by a complicated neural network consisting of sleep- and wake-promoting neurons located in several areas, including the Preoptic Area, hypothalamus, and locus coeruleus90. Orexin neurons in the hypothalamus play a major role in sleep homeostasis by activating wake-promoting neurons directly and indirectly91, and orexin neurons also are an important point of interconnection between the homeostatic and circadian neural circuits92,93. Unlike sleep-promoting neurotransmitters such as GABA, orexin release seems to be primarily regulated by the circadian system, and orexin levels peak a few hours prior to sleep onset in both diurnal and nocturnal animals94,95. The orexin pathway also may feed back onto the circadian system and affect sleep/wake rhythms96,97. Orexin knockout mice show more fragmented sleep and wakefulness with more frequent transitions between these behavioral states mimicking the clock mutant mouse model98. For example, a deficiency of orexin neurons can lead to serious sleep dysfunction and narcoleptic phenotypes76. Effects of orexin A and B differ slightly, with orexin A having higher CSF levels compared to orexin B76. It was found that, in comparison with controls, increased orexin A levels were detected in the CSF of patients with MCI. Further, orexin concentrations in CSF were higher overall in AD patients suffering from sleep complaints compared with AD patients with fewer sleep complaints98. Similarly, when APP/PS1 mice received orexin-A, cognitive impairments worsened and Aβ accumulation increased99. However, the time of day at which orexin-A was administered was not reported, making these results difficult to interpret. In terms of sleep architecture, REM sleep was reduced in AD patients, and had a negative correlation with orexin CSF levels74, though REM changes in AD may have more to do with degeneration of the cholinergic nucleus basalis of Meynert than orexin changes100. These findings suggest that the orexin system is involved in AD. More recently, a significant positive correlation was found between CSF orexin-A levels and cognitive function in AD patients, which suggests that daytime orexin activation may also facilitate cognitive function in AD101. Further, in humans the amount of interstitial fluid Aβ increased during sleep deprivation and orexin infusion, but decreased after infusion of the DORA almorexant46. This study also found that in APPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice, chronic sleep restriction increased Aβ plaque formation, while Orexin blockade with almorexant decreased Aβ plaque formation. However, DORAs may not be able to remove plaques once they have formed, because a different DORA (dora-22) was not able reduce the number of plaques in the a mouse with aggressive aggregation, specifically the 5xFAD mouse33. Further, knocking out the Orexin gene in APP/PS1 mice suppresses Aβ plaque formation102. These findings indicates that DORAs may be able to restore the sleep-wake cycle and reduce amyloid and tau aggregation as a result (Fig. 3).

Top. Depiction of hypothetical CSF Aβ fluctuations in a mouse with Aβ and Tau aggregation. AD pathology is thought to lead to lower glymphatic clearance during sleep/wake cycles and as a consequence higher Aβ production. Bottom. Regardless of the exact mechanism, if clearance is occurring during sleep, then improving sleep quality to reduce fragmented sleep may be one strategy to slow AD further Aβ and Tau aggregation. Treating AD mice with Dual Orexin Receptor Antagonists (DORAs) could potentially regulate Aβ fluctuations during sleep/wake cycles by increasing glymphatic clearance and lowering net Aβ production. This figure was generated using BioRender.

DORAs as a Promising Therapeutic Class for Preventing Progression to AD or Improving Sleep for Those Diagnosed with AD

Suvorexant

DORAs have an overall good tolerability and safety profile without indications of rebound insomnia, withdrawal or dependence potential103. Suvorexant, the first FDA-approved DORA, specifically antagonizes by reversibly binding two orexin receptors, OX1R and OX2R, which play roles in wakefulness and arousal22,90. Suvorexant improves sleep quality, onset and maintenance in patients with insomnia. Use of suvorexant in animal models of AD suggested the potential for beneficial effects in humans. In APP/PS1 mice, suvorexant treatment effectively ameliorated cognitive impairments, alleviated impairments in hippocampal long-term potentiation, and reduced Aβ deposition in the hippocampus and cortex, suggesting that suvorexant could be beneficial for prevention and treatment of AD. One study found that suvorexant promoted REM sleep in both male and female rTg4510 mice (a bi-transgenic tauopathy model), without affecting wake or NREM sleep, similarly REM sleep also is increased by suvorexant in normal humans104. Clinically, suvorexant may be a favorable option for AD patients, because it reduced Aβ deposition in the hippocampus and cortex, suggesting that suvorexant could be beneficial for prevention and treatment105. A 2018 clinical trial found that suvorexant is an adequate treatment for sleep disturbances and insomnia in AD patients and patients with probable AD106. Suvorexant does not alter the underlying sleep architecture in AD patients with insomnia, contrasting results in normal humans and tauopathy mice for which REM, but not slow wave sleep, was increased107. Given that amyloid is reduced during sleep in AD, improving total sleep time may be beneficial for clearing excess waste and toxic accumulation of metabolites. Another study showed suvorexant improved sleep and acutely decreased tau phosphorylation and Aβ in the human CNS, which was measured via PET imaging and/or lumbar puncture107. This extremely promising finding suggests that ameliorating sleep disturbances can have lasting effects on AD TAβA as well as cognitive deficits.

Analysis of suvorexant in elderly populations through phase 3 clinical trials has indicated its safety and efficacy, and this drug is well tolerated after multiple doses108. However, in instances where patients have been on another medication for insomnia previously, higher incidences of adverse drug reactions and dependence were reported109. Suvorexant was reported to have aided in reducing nocturnal delirium in elderly AD at severe and acute levels compared to trazodone, risperidone and quetiapine110. It is notable that when nocturnal delirium is present, it is less severe with suvorexant than with other commonly prescribed insomnia drugs. Thus, suvorexant has the potential to be used to prevent progression to AD and to treat its symptoms, even if the end result is that progression is slowed but not halted.

Lemborexant

Lemborexant promoted REM and non-REM sleep in equal proportions in wild-type mice and rats111. Chronic dosing was not associated with a change in effect size or sleep architecture. Lemborexant did not increase the sedative effects of ethanol or impair motor coordination, showing a good safety margin in non-human animals111. Lemborexant treatment reduced activity during lights-on, and increased activity in the latter half of lights-off, demonstrating a corrective effect on overall diurnal rhythm in SAMP8 mice compared to mice that did not receive a DORA111. Lemborexant can treat symptoms in AD and irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder such as daytime sleepiness, decreased total sleep time, and increased sleep fragmentation112. Recent clinical trial data for use of lemborexant in humans has found the drug to be both safe and effective long-term in adults with insomnia for a number of sleep parameters and various doses113,114,115,116. Thus, lemborexant is another DORA that the potential to be used to prevent progression to AD and to treat its symptoms.

Daridorexant

Daridorexant is another FDA-approved DORA that entered the market in 2022 and has undergone several clinical trials proving its effectiveness for insomnia. In rats, daridorexant increased duration of REM and non-REM sleep and decreased total wake time, and it showed a similar activity profile in dogs117. In rats, daridorexant was found to attenuate fear/stress responses in experimental models that simulate endophenotypes that are specific for post-traumatic stress, obsessive-compulsive and social anxiety disorders, suggesting a potential added benefit in AD populations for which anxiety is also prevalent118,119. Comprehensive clinical trials have been reported with daridorexant at 25–50 mg for a 3-month period and found improvement in a number of sleep parameters at one or both doses119. It has been used successfully in elderly people with insomnia disorder and patients suffering from AD119,120. When considering abuse potential, studies in rats treated chronically with daridorexant showed no signs of withdrawal symptoms, consistent with human studies that demonstrated lower scores in a drug-liking visual analogue scale (VAS) compared to suvorexant and zolpidem121, suggesting potential benefits over suvorexant.

Long Term Efficacy of DORAs

The long-term safety and efficacy of daridorexant has been demonstrated in a Japanese population for 52 weeks [4.3 years122]. Similarly, lemborexant has been shown to be safe and effective for 1 year123. Further, a systematic review of clinical trials for suvorexant revealed that this DORA has also been shown to be safe and effective for up to one year124. Thus, a potential concern for DORAs is that they are new, so less is known about long-term efficacy and safety; however, all available data to date suggests that DORAs are safe and effective for up to 4.3 years.

Targeted Orexin Drugs

Thus far, attempts to use more specific orexin system manipulations in the context of AD are lacking or inconclusive. Chronic blockade of a specific orexin receptor (OX1R) via a selective OX1RA antagonist (SB-334867) leads to impairments in short-term working memory, long-term spatial memory and synaptic plasticity in female 3xTg-AD mice along with increased levels of soluble Aβ oligomers and phosphorylated tau, and decreased PSD-95 (a protein found at the connection between neurons that is thought to be related to brain plasticity such as the plasticity thought to underlie learning and memory) expression in the hippocampus125. These findings indicate that the detrimental effects of SB-334867 on cognitive behaviors in 3xTg-AD mice are closely related to the decrease of PSD-95 and depression of synaptic plasticity caused by increased Aβ oligomers and phosphorylated tau125,126. However, this drug was administered right before the active phase, so these detrimental effects could be related to inducing sleep when mice should be awake, and administering the drug before the inactive phase could have very different results.

There Is Not a Strong Alternative to DORAs for Treating Sleep Disturbances in AD

Melatonin and ramelteon can improve latency to sleep time, but not total sleep time or sleep efficiency, and the high doses necessary for these improvements lead to adverse effects

Melatonin is an endogenously produced hormone that decreases with age and in patients with AD127. Melatonin can improve sleep efficiency to an extent and aid in behavioral symptoms related to circadian dysfunction, such as sundowning128. However, actigraphy (wearable-based activity measurements) data has shown that Melatonin is not an effective mechanism for fully reversing sleep disturbances in AD127. Chronic administration of high Melatonin doses to increase nocturnal total sleep time was found to elevate daytime Melatonin levels, which negatively affect nighttime sleep. These findings are consistent with several other studies showing that Melatonin is only somewhat effective in AD patients when given in higher doses, but chronic administration has an adverse effect on the circadian rhythm127,129,130. Thus, Melatonin is not a suitable option for treating sleep disturbances in AD. Similar issues arise when considering ramelteon, the first selective Melatonin receptor agonist, as an alternative therapeutic for sleep disturbances. Ramelteon has some positive effects in improving some sleep measures but only during the first week of treatment and not consistently thereafter131. Other studies have found a lack of meaningful effect on sleep132 and reported multiple adverse effects compared to placebo31,132. Thus, Melatonin and ramelteon may not be ideal for preventing progression to AD or treating patients with AD.

Benzodiazepines and Nonbenzodiazepine benzodiazepine receptor agonists (NBBZRAs) have dangerous side effects, can create amnesia and increase fall risk, and can even increase risk of developing AD

Benzodiazepines are a commonly used class of drugs for insomnia, and are frequently used for patients with AD, potentially in part due to the lack of alternatives until recently133. There is some debate on the protective effect that these drugs may have, with some evidence for reducing tau phosphorylation, neuroinflammation and slowing AD progression. However, these drugs, such as lorazepam and triazolam, can have adverse side effects such as amnesia, risk of dependence and abuse, risk of falling, impaired coordination, dizziness, and cognitive decline, especially concerning in an aged population vulnerable to falls134,135. Finally, triazolam does not provide beneficial effects in AD patients with disrupted sleep136. NBBZRAs include zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon and zopiclone, and have been studied in older patients with insomnia and/or AD137,138. In rodents, zolpidem, a GABA-A receptor positive allosteric modulator, decreased wake time in the inactive phase and increased NREM sleep in both male and female rTg4510 mice (a transgenic tauopathy model) compared to controls104. However in humans with high doses of zolpidem in the first year of use or extended use and with underlying diseases, such as hypertension, stroke and diabetes, there were significant increases in risk of developing AD compared to non-zolpidem users139,140. Another study also found that increased dementia risk was associated with zolpidem use in elderly populations, especially when used over extended periods of time and with underlying diseases, such as hypertension, stroke and diabetes140. Other drugs in this same class, such as eszopiclone, zaleplon, as well as zolpidem, also have been associated with serious injuries or fatalities in elderly patients with complex sleep behaviors, such as sleep-walking and other NREM-related parasomnias141. Thus, with the abuse potential and noted side effects of acute cognitive and memory impairment, Benzodiazepines and NBBZRAs may not serve as a good therapeutic option for preventing progression to AD or treating patients with AD, who already have substantial memory and cognitive deficits. The key differences between sleep medications are summarized in Table 1.

Trazadone is sometimes used for treating sleep disturbances but may cause memory impairments

There are also instances for which patients are prescribed an antidepressant, such as trazodone, to aid in sleep disorders that include primary insomnia and depression-related insomnia. Trazodone is a serotonin-2 antagonist-reuptake inhibitor (SARI) and is not FDA-approved for the treatment of insomnia. Although positive effects on sleep from trazodone use have been reported in AD, trazodone has been reported to impair anterograde memory in humans the following morning after its bedtime administration the previous night142. Thus, trazadone may not be ideal for preventing progression to AD or treating patients with AD given the impacts on memory.

Atypical antipsychotics, such as quetiapine, are not approved for treatment of insomnia and can cause adverse side effects when used for this purpose

Quetiapine is an atypical antipsychotic drug and is commonly used for the treatment of insomnia. Antagonism of histamine H1 receptors is one of the mechanisms of quetiapine, which may enhance sleep in patients with psychotic and mood disorders. While a good option for some patients, there are adverse side effects such as metabolic syndrome and sleep apnea. Quetiapine, like other atypical antipsychotics, carries an increased risk of death in elderly dementia patients. Individuals who are at risk for progression to AD and patients with AD or are generally elderly, and thus have overall slower metabolic states that would exacerbate the side effects of this medication and cause substantial weight gain and hyperlipidemia alongside sleep apnea90. In addition, a common side effect of quetiapine is daytime drowsiness and sedation. Finally, while this drug and several others in its class do have sedative and sleep-inducing effects, they are not FDA approved for treatment of insomnia. As with antidepressants, prescribing antipsychotic medications off-label can cause issues when being considered for preventing progression to AD or for AD-related treatment plans if they cannot be directly prescribed and validated for the desired purpose.

Conclusions and Future Directions

AD directly and indirectly effects a large portion of the world population. With no current cure, there is a strong need for preventative and therapeutic measures to aid AD patients. A vicious cycle between sleep disturbances and AD pathophysiology has been established: AD-related cognitive and pathophysiological decline lead to sleep disturbances, and sleep disturbances worsen AD pathophysiology. In both respects, a mechanism for this linkage is desperately needed so that appropriate amelioration strategies can be designed. It has been established that the glymphatic system plays a significant role in brain waste clearance, providing a potential mechanism linking reduced sleep in AD to further deterioration. However, while there are many papers providing evidence that this system is primarily active in clearing waste during sleep, a recent paper has suggested that more research is needed due to limits in methodology used to assess glymphatic clearance. Further research is needed to understand why circadian disruption leads to less effective waste clearance of toxic metabolites that accumulate in the brain during wakefulness, why amyloid is reduced during sleep in mice modeling amyloid and tau aggregation aspects of human AD, or why there is a relationship between AQP4 and amyloid clearance during sleep. Regardless of the precise mechanism, a favorable approach is to target and ameliorate sleep disturbances in AD to enhance the circadian clock and clearance of aggregates during sleep to restore or at least maintain cognitive functioning. Over the years, there have been a plethora of drugs prescribed and used to aid in restoring the sleep-wake cycle and circadian rhythm in AD patients. However, most of these drugs are prescribed indirectly for other intended uses, have adverse side effects, cannot be taken chronically, have high abuse potential, or other issues. There is a need for a safe and efficacious therapeutic for AD patients. Recently, a new class of drug has emerged – the DORAs. These drugs block the wakefulness effects of orexin and facilitate sleep. Present data suggest that these drugs are effective at relatively low doses when taken chronically and seem to have limited adverse side effects. While suvorexant, lemborexant and daridorexant are FDA approved to treat insomnia, other DORAs are seeking approval and are being tested in clinical trials and laboratories. This review analyzed current literature focusing on the background and need for therapeutic aids for sleep disturbances in AD, why many current drugs on the market may not be the best option for patients, and how DORA drugs may be a new and better alternative in treatment of this ongoing issue. There is now a critical need to understand the relationship between DORAs and AD pathophysiology, if these drugs can impact this pathophysiology positively, and the mechanisms and monitoring of such effects so that future treatment can be tailored accordingly.

Responses