Earthquakes yes, disasters no

Introduction

After the 1755 Great Lisbon earthquake, German philosopher Immanuel Kant wrote: “If people build on inflammable materials, sooner or later the whole splendour of their buildings can be destroyed by shaking”1. Moreover, Kant mentioned in the same essay that earthquakes cannot be stopped, but disasters can be prevented, implying the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) that was already impending. These statements have a broader impact today. Earthquakes and other natural hazard events are not drivers of disaster losses but vulnerability and exposure to the events2,3. If nations are not prepared to prevent or significantly mitigate risks of extreme events, and if people do not know about the risks they live, one day they will face a disaster. Earthquakes will happen (yes) while the lithosphere dynamics generates tectonic stresses. However, disasters caused by earthquakes can be prevented, and then we would say disasters no.

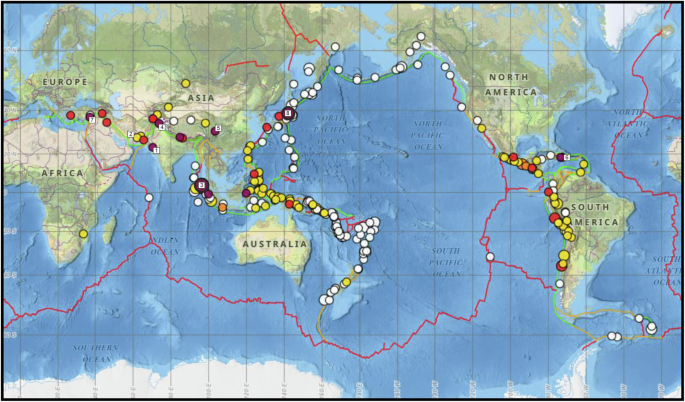

Disasters caused by earthquakes (or earthquake disasters, see Box 1) have been mostly associated with populated and vulnerable areas (see Supplementary Fig. 1 in Supplementary Information). Earthquake disasters have significantly increased since the onset of the 21st century. In terms of the impact (the number of fatalities), seven of the ten deadliest disasters and three costliest disasters of this century were caused by earthquakes (Fig. 1; and Supplementary Table 1 in the Supplementary Information). Earthquake disasters have a significant impact on both developed and developing nations, as well as various sectors of the economy at local, national, and regional scales; hence, they have the potential to adversely affect a wide range of United Nations Sustainable Development Goals.

The coloured circles show the number of casualties associated with the earthquakes: more than 1001 deaths are marked by brown; 101 to 1000 by red; 51 to 100 by orange; 1 to 50 by yellow; and no deaths by white). The circle’s size indicates the earthquake magnitude M: big, middle, and small circles are associated with earthquakes of M ≥ 9, M ≥ 8, and M ≥ 7, respectively. The seven deadliest earthquakes are marked by white squares marked with number: 1, the 2001 Gujarat M7.6 earthquakes (EQ); 2, the 2003 Bam M6.6 EQ; 3, the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman M9.1–9.3 EQ and tsunamis; 4, the 2005 Kashmir M7.6 EQ; 5, the 2008 Sichuan M7.9 EQ; 6, the 2010 Haiti M7.0 EQ; and 7, the 2023 Türkiye-Syria M7.8 EQ. Three costliest (adjusted for inflation in 2023) disaster events are the 2011 Tohoku M9.0-9.1 EQ (marked with number 8) and triggered tsunamis ( ~ US$ 320B), the Sichuan EQ and triggered landslides ( ~ US$ 212B), and the 2023 Türkiye-Syria EQ ( ~ US$ 163B). Red (divergent), orange (convergent) and green (transform) lines mark the plate boundaries. The map is generated using an online software by the NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/maps/hazards).

According to CRED-UNDRR data4, the economic losses from 552 earthquakes recorded between 2000 and 2019 amounted to a staggering US$ 636B. This accounts for approximately 21% of the total recorded economic losses from disasters worldwide. The vulnerability of contemporary society to seismic occurrences continues to escalate, mostly due to the urban population growth in earthquake-prone regions complicated by people migration because of conflicts or climate change, the increase in the quantity of high-risk structures, and socio-economic problems including extreme poverty.

Recent advancements in the research fields of geoscience, seismic hazard monitoring and assessments, earthquake modelling and forecasting, earthquake engineering, and earthquake risk and resilience assessments as well as in the development of modern national and international seismological networks5 and earthquake early warning (EEW) systems6 have contributed to a better understanding of earthquake disasters. These advancements have played a crucial role in preparing for, responding to, and adapting to potential disruptions resulting from earthquakes.

This paper aims to provide an answer to the question of why large earthquakes sometimes turn into disasters. After this introduction, studies on the lithosphere dynamics and large earthquake occurrences are overviewed. Seismic hazard assessment methodologies and cascading hazards triggered by large earthquakes are then discussed. Earthquake forecasting, as a component in comprehensive hazards and risk assessments, is still unknown of knowns; basic earthquake prediction methods are reviewed. Important aspects of earthquake risk analyses as well as preventive disaster mitigation measures and risk communication issues are further discussed. Knowledge gaps and outlooks related to earthquake hazard and risk science, vulnerability studies and earthquake engineering, and integrated research on disaster risks are then presented followed by concluding remarks.

What we know about large earthquakes

The lithosphere dynamics and large earthquakes

The most powerful earthquakes are observed at oceanic trenches along the subducting lithosphere (Fig. 1). Large earthquakes (magnitude ≥7) also occur within the continental lithosphere, particularly in areas of continental collisions, rifts, and grabens7. During an earthquake, a portion of the released energy creates elastic waves propagating throughout the Earth. These waves produce abrupt ground motions and shaking, which can sometimes lead to structural damage or collapse, landslides, tsunamis, and other cascading hazards8.

The lithospheric plates split into smaller geological units, referred to as blocks, by thin fault planes serving as pathways for adjacent blocks to move in response to friction and plate motion9. The complex movements of blocks and faults reflect the nonlinear dynamics of the lithosphere, which exhibits features of a hierarchical dissipative system producing critical events, referred to as extreme seismic events10,11. Friction traps blocks along faults for decades to millennia, and tectonic strain and stress increase during these periods. When the stress exceeds the strength of the blocks and the strain exceeds frictional forces preventing slip, the blocks on both sides of the fault plane experience rapid sliding causing fault rupture (or earthquake). An earthquake results in a stress drop followed by stress redistribution. Subsequently, an elastic strain building commences again, initiating a seismic cycle that repeats along the fault. (Note that this paper focuses on earthquakes caused by sudden fast slip along a fault and not slow earthquakes that release energy over hours to months).

Earthquakes are generated at seismic patches of a fault, while no earthquakes occur at aseismic patches, and the fault slips continuously at conditionally stable patches. Meanwhile, these conditionally stable patches may undergo seismic slippage, when they are exposed to abrupt tectonic forces due to the failure of adjacent seismic patches. This slippage can result in a far greater earthquake than what would be anticipated from seismic patches alone12. Earthquake occurrences are regulated by the interaction between stress localization and frictional interface failure. Experimental studies on stress localization at a fault interface support the notion that stress nonuniformity is a crucial factor in regulating both frictional stability and fault dynamics13. The integration of field observations, geodetic studies, and remote sensing measurements enables the analysis of deformation patterns resulting from surface ruptures caused by large earthquakes14,15. Information on the surface ruptures and related deformations can be used by civil protection authorities in managing earthquake emergencies during an ongoing seismic crisis.

Understanding of lithosphere dynamics and large earthquake occurrences has been achieved through studies of deformations around faults and rupture processes13,15,16,17, stress localisation in the lithosphere and stress redistribution after fault slip18,19, and earthquake simulations20,21. Earthquake simulators enable the generation of synthetic earthquake catalogues that encompass extended time periods compared to those that represent recorded earthquakes. For example, an earthquake simulator, known as a block-and-fault dynamics model22, can generate synthetic events over a span of several thousand years identifying possible sites of large earthquakes. This model identified great seismic events with magnitudes greater than 9 in the northwestern section of the Sunda Arc23, where the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman M9.1–9.3 earthquake occurred. Similarly, this model identified a group of significant earthquakes (M > 7.5) along the Longmen Shan fault24, where the Sichuan M7.9 earthquake took place in 2008.

There are various other approaches for identifying the locations of large seismic events. Pattern recognition and machine learning have been assisting in identification of large seismic events within seismogenic nodes25. The seismogenic nodes formed at the intersections of lineaments (e.g., faults) can be identified by geomorphic, tectonic, geological, and topographic data analysis26. Juxtaposing the sites of large seismic events identified by pattern recognition methods with the epicenters of the earthquakes that happened after publications of the results of relevant studies shows that 86% of earthquakes occurred within the recognized seismogenic nodes27. The sites of large earthquakes can be forecast using the U.S. National Seismic Hazard model28, which was initially developed in 1996 and periodically updated29. It is feasible to predict the location and the anticipated frequencies of larger earthquakes by utilising the occurrence rates of previous M > 4 earthquakes worldwide30 or the cumulative Benioff strain derived from prior seismic events31.

Seismic hazard assessments

Within the field of seismology and earthquake engineering, seismic hazard is specifically defined in relation to engineering characteristics associated with strong ground motion, such as peak ground velocity/acceleration or seismic intensity. A broader concept of seismic hazard is outlined in Box 1. The process of seismic hazard analysis (SHA) relies on studies of seismic wave excitation characteristics at the source, seismic wave propagation (from the earthquake hypocentre to the sites of interest, accounting for wave attenuation), and site effects (e.g., subsurface soil conditions and/or liquefaction at the site)32,33,34. Site effects may amplify earthquake ground motions. For example, the 1985 Michoacan (Mexico) M8.0 earthquake caused strong ground motions leading to serious damage to the Mexico City situated at about 400 km distance from the earthquake epicentre. This damage was a result of the amplifications of the ground motions through the soft lacustrine clay deposit surrounded by hard volcanic rock formations35.

SHA commonly employs two primary methods, deterministic (DSHA) and probabilistic (PSHA). The DSHA method focuses on credible critical earthquake scenarios and relies on analysing seismic energy attenuation as a function of distance from the earthquake sources. This enables the determination of the level of ground motion at a certain site. The estimates of ground motion consider the influence of specific site conditions and utilise existing knowledge regarding earthquake sources and the processes of wave propagation. Although the DSHA typically does not consider the frequency of ground motion, it is still a reliable method for assessing the seismic hazard of critical infrastructure (e.g., nuclear power plants, chemical and military plants, pipelines, and dams). The DSHA utilises existing data on earthquakes characteristics and the physical models that represent our current knowledge of earthquake phenomena33. This method is valuable for making informed decisions because DSHA outcomes are the estimated values of earthquake ground shaking and not the probabilities of the ground shaking exceedance.

The PSHA method addresses the rates at which certain levels of ground motion are surpassed during a specific period of time32. To conduct a PSHA at a specific location and develop a hazard curve (that is, a plot of the annual frequency of ground motion exceedance versus peak ground accelerations), the following primary elements are necessary: the proximity of the site to known or assumed earthquake sources; the anticipated recurrence pattern of these earthquake sources; and the calculated ground motion for the earthquakes occurring at the designated site36,37. The probabilistic analysis considers uncertainty in the earthquake source, path, and site conditions. Probabilistic seismic hazard maps differ from deterministic maps in that they do not depict actual ground shaking at a specific location. PSHA has faced a criticism in recent decades due to the occurrence of large and destructive earthquakes in regions that PSHA has identified as having a low probability of significant ground motion33,37,38,39,40.

The neo-deterministic SHA method41 is based on simulating earthquake ground motion using synthetic seismograms. Information regarding the regional lithosphere structure, regional seismicity, seismic source processes, and propagation of seismic waves is used to compute realistic synthetic seismograms40,41. The CyberShake SHA approach42 integrates deterministic sources and wave propagation effects into hazard assessments by employing physics-based simulations of ground motion triggered by fault ruptures. According to this approach, multiple rupture variations should be identified, and synthetic seismograms should be then computed for each rupture variation to determine a waveform-based seismic hazard estimate for a certain site. Hazard curves for the site are then developed by extracting peak intensity values from synthetic seismograms and integrating them with the original rupture probabilities42.

Information regarding the occurrence of large earthquakes in a certain area is normally insufficient for SHAs due to their infrequency. The utilisation of earthquake simulators for modelling seismic occurrences can effectively address the challenge by integrating observations, historical data, and modelled outcomes43,44,45. For instance, a data-enhanced SHA method43 employing a Monte-Carlo PSHA combines regional observed seismicity with large magnitude synthetic events derived from physics-based earthquake simulations. PSHA approaches often rely on pointwise (site by site) assessments of ground shaking. However, the anticipated ground motion level in a chosen region (comprising many sites) is greater than that observed at individual sites. A multi-level approach to SHAs integrates a conventional pointwise hazard assessment inside a designated earthquake-prone area and a multiple-site hazard assessment for urban and industrial zones within the same area that holds significant socio-economic value46.

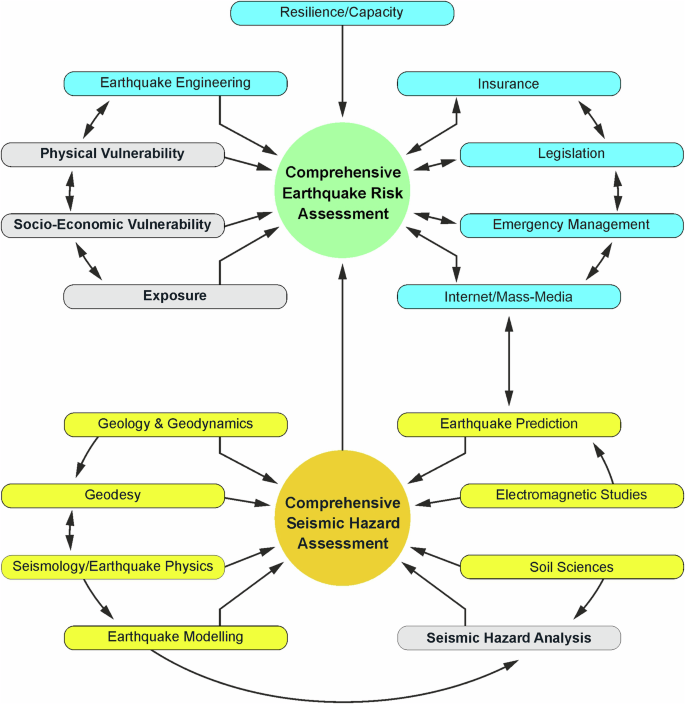

SHA methods have their strengths and weaknesses33. Neither method can provide fully reliable information on seismic hazards, especially those related to infrequent events. Therefore, a combination of various approaches in SHAs could enhance hazard assessments providing useful information for engineering purposes, earthquake risk assessment, and emergency planning. Finally, a comprehensive seismic hazard assessment (Fig. 2) should be based not only on seismological and soil science components for the analysis of ground motion parameters, but also on knowledge from geology, geodynamics, geodesy, electromagnetism, and earthquake physics to better understand large earthquake occurrences.

CSHA encompasses a detailed seismic hazard analysis (including an assessment of ground motion parameters and the earthquake intensity) accounting for the local and regional geology and geodynamics, geodesy, seismology (including paleoseismology), earthquake physics, modelling and prediction, soil science (including assessments of seismic wave amplification and site effects), and electromagnetic studies. CSHA is a component of the CERA, which combines traditional assessments of the physical and socio-economic vulnerability and exposure to earthquakes with engineering solutions on earthquake resistant constructions, studies of resilience and capacity of the societal groups to prepare, cope with, respond, and adapt to possible disruptions due to disasters. The inclusion of various stakeholders involved in disaster risk reduction, such as government representatives, emergency management authorities, the insurance industry, legislation sector, and mass media representatives, should be considered in the CERA. This consideration is crucial for promoting risk financing, enhancing preparedness and awareness regarding risks, and advancing risk communications, among other significant risk reduction issues. Arrows indicate links between the components. Colours mark traditional assessments (grey), additional components (light yellow) of CSHA (dark yellow), and additional components (cyan) of CERA (light green). The figure is modified after ref. 113 and generated using the Adobe Illustrator 28.4.

Earthquake-triggered cascading hazards

A large earthquake may trigger other hazard events (Fig. 3), often referred to as cascading hazards (Box 1), including landslides (e.g., the 2008 Sichuan M7.9 earthquake-triggered landslides47), tsunamis (e.g., the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman M9.1-9.3 earthquake-triggered tsunamis in the Indian Ocean48), dam breaks and flooding (e.g., the 1965 Chile M7.4 earthquake-triggered sand liquefaction and resulting failures of sand dams with subsequent flooding, which resulted in fatalities and widespread contamination of an agricultural valley49), fires (e.g., several cases of earthquake-triggered fires in electric power and industrial facilities50), epidemics and disease outbreaks (e.g., several cases of infectious disease outbreaks following earthquakes in Europe51), environmental hazards (e.g., environmental and health hazards due to the 2023 Türkiye–Syria earthquake52), and technological hazards (e.g., the 2011 Tohoku M9.0–9.1 earthquake-triggered powerful tsunami followed by seawater inundation and flooding, which led to a loss of power in the cooling systems, core meltdowns at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, and the nuclear incident53).

A single large earthquake may trigger different types of hazard events: geohazard, such as strong aftershocks and remote large earthquakes, liquefaction, uplift or subsidence, subaerial or submarine landslides; hydrological hazards, namely, flood or tsunami; technological hazards, such as dam failure, building collapse, fire, nuclear plant failure, water supply and supply chain failure; societal hazards, e.g., financial shocks and military conflicts; biological hazards, such as infectious disease (e.g., cholera) and serious mental health issues; and environmental hazards, such as land degradation and salinity. Hazard types and specific hazards names are taken from the Hazard Information Profiles114. The black and colour arrows show secondary and tertiary hazards, respectively. Generated using the Adobe Illustrator 28.4.

A large earthquake is normally followed by aftershocks, i.e. earthquakes occurring after the mainshock in the vicinity of the mainshock epicentre due to stress changes. Although aftershocks typically have a smaller magnitude than the mainshock, there are instances where aftershocks can be of comparable magnitude causing further damage and exacerbating the disaster due to the mainshock. For instance, the 2015 Gorkha (Nepal) M7.8 earthquake resulted in numerous aftershocks with M ≥ 4 within several months after the earthquake. The most significant M7.3 aftershock, occurring three weeks after the mainshock, caused a strong ground motion resulting in additional damage/destruction to the buildings, monuments, and infrastructure that were previously damaged by the mainshock54.

Large earthquakes can remotely trigger other earthquakes. For example, the 1992 Landers M7.3 earthquake triggered earthquakes, which occurred at distances up to 1250 km from the Landers mainshock55. The 2023 Türkiye–Syria M7.8 earthquake triggered the M7.6 earthquake at about one hundred km from the epicentre of the M7.8 earthquake. This earthquake doublet caused hundreds of M ≥ 4 aftershocks within several days with the strongest M6.7 aftershock that occurred in a few minutes after the M7.8 mainshock56. Aftershocks increase the number of casualties due to building collapses and worsen the humanitarian catastrophe, impeding the relief and rehabilitation endeavours, hence complicating the responders’ access to the impacted regions. Aside from inflicting physical harm, large earthquakes followed by significant aftershock activities may have mental health issues associated with affected people52.

A powerful earthquake alters the stress distribution in the soil and the uppermost sedimentary layers of slopes. This stress alteration can lead to a slope instability when the resisting shear forces of the slope are reduced57. Landscape modifications and disruptions to a slope equilibrium can contribute to the slope instability and the dynamics of landslides58. The majority of large earthquakes trigger ground displacements and landslides; some can cause rivers and lakes to be dammed, resulting in the collapse of dams over a period of days to centuries. Landslides that are internally disrupted can be triggered by even the slightest shaking, while deeper-seated slides necessitate more intense shaking57. The occurrence of substantial human casualties was linked to rock avalanches, rapid soil flows, and rock falls, and the extent of landslides exhibited a positive correlation with earthquake magnitude57.

Earthquakes occurring beneath the ocean floor have the potential to trigger tsunamis and submarine landslides. In the case of thrust faulting earthquakes, tsunamis are generated due to sudden vertical displacement of the ocean floor and the consequent upward movement of the water column above the mean sea level. The tsunami amplitude is significantly influenced by the earthquake directivity resulting from rupture propagation along the fault, rather than by the earthquake source depth and focal geometry59. While earthquakes and landslides occur locally, the impacts of tsunamis are spatially and temporally dispersed, with potential global ramifications. For example, the tsunami triggered by the 2004 Sumatra-Andaman M9.1–9.3 earthquake had an impact on many countries around the Indian Ocean.

Earthquakes can trigger not only secondary hazard events but also tertiary and further events in time and space (Fig. 3) or increase the probability of their occurrence60. The 1964 Alaskan M9.2 earthquake triggered submarine landslides resulting in a tsunami61 and regional subsidence leading to an increased probability of flooding62. In the case of the 2008 Sichuan M7.9 earthquake, approximately 200,000 landslides occurred in the region. Following the initial event, a significant number of these landslides were reactivated within a few years due to rainfall, leading to occasional catastrophic debris flows63.

Buildings and infrastructure that are partially damaged during earthquake ground motion may be more susceptible to strong aftershocks because of an increase in the probability of additional damage to structures that were previously weakened by the mainshock. Therefore, evacuation from damaged buildings after a large earthquake is imperative. However, weather conditions may hinder prompt evacuation to safer areas, as it happened during the 2023 Türkiye-Syria earthquakes and led to further injuries and fatalities during subsequent aftershocks52. Additionally, the occurrence of a large earthquake has the potential to trigger a fire in the event of malfunctioning gas-water heaters in buildings64.

Earthquake-triggered cascading hazard assessments provide certain difficulties in comparison to seismic hazard analysis. These problems arise from the distinct characteristics of hazard occurrences and various approaches used for assessing individual hazards as well as vulnerabilities65. Furthermore, the evaluation of risks associated with a cascading hazard is somewhat intricate; for instance, an earthquake may have a lesser societal impact than a triggered event, such as a tsunami. Occasional hydro-meteorological events during or immediately after the earthquake disaster, such as tropical storms or hurricanes, can lead to further damage and collapse of buildings and infrastructure and, hence, worsened the disaster.

What we do not know about large earthquakes

We do not know exactly when and where a large earthquake will occur. Currently, accurate and reliable earthquake prediction with sufficient precision to warrant actions, such as evacuations, is exceedingly challenging37. The perception of earthquakes as unpredictable phenomena is reinforced by the suddenness, seeming irregularity, and infrequent nature of extreme seismic events66. The field of earthquake prediction research has been the subject of extensive debate, with differing viewpoints on the feasibility of prediction67,68,69.

Earthquake prediction can be made by monitoring an earthquake precursor, which serves as an indicator of an impending large earthquake, and raising an alarm when the precursor exhibits anomalous behaviour. The seismic precursors can be classified into various overarching categories: biological, electromagnetic, geochemical, geoelectrical, hydrological, physical, thermal, and others66. While several observations indicate atypical alterations in natural fields during the proximity of a large earthquake, most of these reports document a distinct case history and lack a comprehensive description70. For instance, by monitoring anomalies in land elevation, ground water level, foreshock activity, and peculiar animal behaviour prior to a large earthquake, Chinese seismologists could successfully predict the 1975 Haicheng M7.3 earthquake. However, using the same precursors, they were unable to forecast the 1976 Tangshan M7.6 earthquake, which became one of the deadliest earthquakes in the history of recorded earthquakes66.

Statistical analysis of seismicity can also serve as a foundation for earthquake prediction methodologies. The alarm-based method for predicting large earthquakes with a magnitude M > 8 involves monitoring and analysing various indicators of seismic activity in a region of interest71. This method could predict 2/3 of great earthquakes that occurred between 1985 and 2019 worldwide72. The short-term earthquake probability technique73 employs aftershock data to generate hourly updates on the probability of strong ground shaking. Short-term forecasts may yield significant probability gains, while the probabilities of potential damaging earthquakes are considerably lower than 0.1 due to the shorter forecasting intervals compared to the recurrence intervals of major earthquakes66.

Although the quality and accuracy of the present-day earthquake predictions are notably inferior to those of weather forecasts, the current capacity for earthquake prediction holds important value in the evaluation of earthquake risk and the enhancement of disaster preparation. This inquiry pertains to the potential integration of existing fundamental scientific knowledge and earthquake forecasting methodologies with risk reduction tactics to provide cost-effective mitigation measures74. This, in turn, enables the potential for future enhancements in earthquake disaster prevention.

What we know about earthquake risks

Earthquake risk analysis

Earthquake risk (Box 1) is quantitatively represented by the convolution of the seismic hazard, vulnerability, and exposure variables. Various methodologies have been developed to assess seismic hazards (see Sect. 2.2), vulnerabilities and risks75,76,77. Earthquake risk models enable the determination of average annual losses and probable maximum losses due to an earthquake of a certain magnitude occurring in a specific region of interest78. These models are intensively employed by the (re)insurance industry as tools for assessing potential earthquake losses.

Assuming that an earthquake has occurred, exposure and vulnerability are the primary drivers that determine earthquake risk and contribute to disaster losses3,79. Moreover, as exposed-to-hazard values increase with economic development, a crucial aspect of disaster risk management becomes the reduction of vulnerability. The 2010 Chile M8.8 earthquake and triggered tsunami caused the loss of several hundred lives, while the 2010 Haiti M7.0 earthquake resulted in a disaster characterised by the loss of several hundred thousand lives because of significant physical and socio-economic vulnerabilities3. Meanwhile, the 2021 Haiti M7.2 earthquake, which occurred approximately 100 km from the 2010 earthquake epicentre, resulted in fewer human casualties (Supplementary Table 1), because the 2021 epicentre was not situated in a densely populated area3.

Earthquake risk assessments conducted for Baku, Azerbaijan80 and Lisbon, Portugal81 have demonstrated that earthquake risk is closely linked to physical vulnerability, namely, to building damage. Despite the Iranian government’s efforts to reduce earthquake risk, the country still faces physical vulnerability that could result in significant losses during a large earthquake82. On the other hand, Japan has effectively implemented its national earthquake risk reduction policy providing resources for building construction and reinforcement. This policy leads to a substantial reduction in earthquake impacts and losses83 and to enhancing resilience (Box 1) of the society.

The resilience is linked to the capacity of a community/society to respond to the impact of large earthquakes or other extreme hazard events, and it describes specific conditions of a community/society to recover from earthquake impacts. Damage to buildings, transportation networks, lifelines, and other critical infrastructure or economic losses can determine the degree of the resilience to earthquake occurrences84. Reducing damage will lead to increasing a resilience to earthquake impacts.

Resilience assessments should consider also economic, social, and behavioural indicators, such as the number of the people affected, gross domestic product per capita, people behaviour during and after earthquake disasters, and the number of beds in hospitals85,86. The combined assessments can provide a scientific knowledge to the actions toward reductions of physical vulnerabilities and earthquake risk. These assessments may help national and local governance to improve resilience at the community level in urban areas87. Still more efforts are needed to increase a resilience of communities in many earthquake-prone regions88.

Earthquake risk and resilience research and their assessments offer a precise and objective scientific perspective on the potential socio-economic consequences of large seismic events and strategies for mitigating substantial human and economic losses89. The inclusion of knowledge from various stakeholders in earthquake risk assessments (Fig. 2) is crucial for enhancing preparedness and awareness regarding risks and advancing risk communications.

Preparedness, public awareness and earthquake risk communication

Preparedness and public awareness are important elements in proactive steps to alleviate disasters associated with earthquakes or other hazards90. They should always accompany efforts to minimize uncertainty in risk assessments and to effectively communicate risks. For instance, Japan is a renowned for its exceptional preparedness for and public awareness of natural hazards and risks. Nevertheless, during the Tohoku earthquake on 11 March 2011, the initial information about the height of tsunami waves was underestimated, and as a reaction, some individuals refrained from evacuation to more secure areas as they believed that seawalls would protect them against tsunamis83.

To effectively convey earthquake risk assessments to stakeholders, it is essential to employ a well-designed risk communication strategy. This strategy should be based on comprehending the risk perceptions of different groups of individuals, considering their level of knowledge on the subject, as well as their requirements and challenges in implementing mitigation measures91.

The risk communication of large earthquakes may be approached in several ways92. Scientists disseminate their expertise by offering astute alerts and ideas pertaining to risk reduction due to forthcoming seismic events (an example of one-way risk communication efforts). In some cases, notifications about an imminent seismic hazard were overshadowed by other concerns, such as political, financial, environmental, and societal matters. For example, scientists recognised that the Enriquillo fault, which is situated in a close proximity to the capital city of Haiti, has the potential to generate a M7.2 earthquake93, and they alerted local authorities. However, no actions were taken before the 2010 Haiti M7.0 earthquake occurred.

Following the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake and the triggered Indian Ocean tsunamis, a collaborative effort in risk communication was undertaken by natural and social scientists in Japan. They conducted a series of meetings with at-risk communities, sharing information about large earthquakes and triggered tsunamis, showing movies of realistic numerical models of tsunami inundations, and engaging people in intensive discussion (an example of two-way communication of risk). Interactions between residents and natural/social scientists not only increase awareness of risks but also involve them in disaster risk reduction (DRR) efforts94. Also, the disaster caused by the 2004 Sumatra–Andaman earthquake/tsunami highlighted the need for an effective coordination in DRR at international and national levels, especially related to the earthquake and tsunami early warning systems95.

Risk communication is essential in regions experiencing minor to moderate earthquakes because these regions typically have lower levels of preparedness for large events than do regions where people frequently encounter moderate to strong earthquakes. For example, the Chilean government acknowledged the substantial risk following the 1960 Valdivia M9.5 earthquake and prioritized its actions related to seismic safety. Meanwhile, the Haitian people were unaware of the risk of large earthquakes and resided in precarious and unreinforced homes that crumbled during the devastating 2010 earthquake. Advances in telecommunications (e.g., cellular telephony including messaging, broadcast networks, and social media platforms) provide the background for timely information on earthquakes contributing to rapid assessments of seismic intensities and to earthquake early warnings96.

Knowledge gaps and outlooks

This section does not aim to address all the knowledge gaps and possible perspectives in the areas related to large earthquakes, seismic and cascading hazard analyses, vulnerability and risk; rather, the most important knowledge gaps are highlighted according to the author’s opinion.

Large earthquake hazard

Despite significant advancements in seismology, several issues remain that continue to pose challenges97. Of particular significance for seismic hazard analysis are the mechanisms by which faults interact and cause large earthquakes, as well as the factors that determine when a propagating rupture comes to an arrest98. One of the main challenges in solving these complex problems is the lack of direct observation of earthquakes and limited in-situ verification of their physical parameters.

The occurrence of large earthquakes in areas with long-lasting earthquake swarms remains an unresolved problem in seismology. The 2024 Noto Mw = 7.5 earthquake took place in an area known for its frequent seismic activity. Over the past three years, this region has experienced thousands of small to moderate earthquakes (seismic swarms), making this seismic event quite unexpected99. Recent investigations related to this earthquake occurrence showed a complex rupture process associated with lower-crust fluid supply to the area of the seismic swarms100,101.

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning techniques have been utilised to monitor fault activities with remarkable spatial resolution102 and to forecast earthquake magnitudes through rupture simulations and using GNSS data103. These techniques could be used in seismic hazard and earthquake prediction104 to improve forecasting outcomes.

Advanced scientific methods and approaches for data analysis and modelling have the potential to improve our understanding of extreme seismic events and hazard assessments. Earthquake simulators that accurately mimic tectonic activity are valuable tools for studying seismicity over extended periods and for assessing seismic hazards43. The development of enhanced earthquake models and of powerful simulators is crucial for enabling interactions within fault networks at scales of less than one hundred meters and hence improving seismic hazard and forecasting capacities.

It is crucial to prioritize multi-hazard analysis and risk assessments and their rapid transfer from theory to informed policymaking. Quite often, decisionmakers are faced with the multiple challenge of mitigating earthquake risks and cascading risks associated with earthquakes105. Enhanced methods for cascading risk assessments should be developed to effectively reduce disaster risks65. Additionally, it is important to improve EEW systems106,107 using geodetic and seismological investigations. Moreover, assimilating the observed wavefield generated by an earthquake into a seismic wave propagation model can aid in forecasting ground shaking for EEW purposes108.

Vulnerability to earthquakes

Vulnerability assessments have significantly improved recently, but there is still no common approach for conducting these assessments, let alone integrating them into a regional-to-global composite assessment. Many places lack disaster risk data, notably vulnerability and exposure metrics. A few national disaster loss and damage databases exist; however, they differ in geographic or temporal coverage, measurement, and classification of beginning hazard or threat producing harm83.

Although building regulations for new and retrofitted structures have improved to withstand earthquakes, there are issues related to vulnerable building structures. These structures can be considered as ticking “time bombs”. A large earthquake can set off these “bombs” leading to the collapse of buildings and causing both human and economic devastation. Wood is often chosen as the preferred material for small houses due to its durability and resistance to damage from ground shaking. However, the 2024 Noto earthquake served as a stark reminder of the vulnerability of wooden buildings: a fire broke out and destroyed hundreds of wooden structures during this earthquake99.

Retrofitting buildings using shaking-resistant materials (and here is a space for engineering solutions and innovations) should be approached with the utmost precision and attention to detail. Undoubtedly, buildings in areas prone to intense ground shaking should be promptly reinforced, much like the urgent defusing of unexploded bombs from past wars. The Yingxian Wooden Pagoda in China, which was constructed in 1056 AD and survived multiple powerful earthquakes, is a prime example of seismic safety. This nearly millennium-old building serves as a powerful reminder of the statement that earthquakes do not kill people but building constructions collapsing due to strong earthquake ground motion do it.

Integrated research on earthquake risks

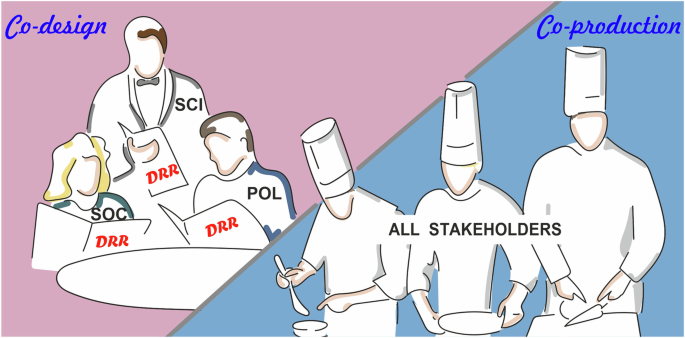

An integrated approach that combines the natural and social sciences and engineering is necessary to understand and reduce earthquake risks. Developing inter- and trans-disciplinary, team-based approaches is crucial for incorporating the contributions of all disciplines and stakeholders into a risk management strategy83. It is also important to foster partnerships among scientists, governments, and all segments of society through co-designed (e.g., sharing ideas and existing knowledge, planning workflow activities, sharing funding, envisaging outcomes, and developing feasible solutions for earthquake risk reduction) and co-produced (e.g., engaging technical experts in different fields of science and engineering to analyse, model, synthesise various outcomes, and to facilitate solutioning for earthquake and earthquake-triggered hazard risk reduction; and creating a collaborative work between the technical experts, decisionmakers, stakeholder, and representatives of local communities) research (Fig. 4). This research should provide practical and policy-focused knowledge in order to implement this knowledge for reducing disaster risks (e.g., adapting technical findings into more meaningful, usable and useful information for decision making)83,109.

While the process of co-designed and co-produced work is rather intricate, it is compared here using a simple analogy with the preparation of a meal at a restaurant115. (Left panel) Scientists (SCI) offer a comprehensive range of information on DRR (“DRR menu”). Policymakers (POL) and stakeholders representing the society (SOC) articulate their requirements and goals for DRR. Following a collaborative deliberation, they collectively co-design the cooperative work (“place an order for a meal”). The willingness of politicians to provide funds for disaster risk mitigation is significantly constrained by a restricted budget. (Right panel) Natural, social and political scientists, engineers, and other stakeholders work together and co-produce a product. This joint product (“cooked meal”) encompasses novel knowledge, risk assessments, and suggestions for informed decision-making. The co-designed and co-produced work has the potential to provide practical and policy-oriented knowledge aimed at (earthquake) risk reduction and hence enhancing the usefulness and applicability of the acquired knowledge. Modified after ref. 115 based on a professional designer’s advice and generated using the Adobe Illustrator 28.4. The rights in the material are owned by a third party.

The scientific community and other stakeholders face challenges in collaborating to understand earthquake disaster risk. Although seismologists have been collaborating with earthquake engineers on seismic hazard assessments for several decades, communication among electromagnetic, hydrological, geodetic, and seismological communities is limited. Communication between natural and social sciences, policymakers, and insurance officials is much harder because stakeholders have different professional experiences in seismic hazard and risk reduction. Hence, multiway communication is needed to help stakeholders understand hazards and risk management choices83,92.

Concluding remarks

Significant knowledge exists on the physical processes and forcing mechanisms that cause large earthquakes. Earthquake hazards have been extensively studied along with investigations into the predictability of extreme seismic events. Yet, disaster losses triggered by large earthquakes impose great challenges for sustainability21. Disasters occur because of the significant vulnerability and low capacity of the society to manage and reduce earthquake risks. They occur not because of earthquakes, but rather because of human decisions related to authorities’ unwillingness to invest in resistant construction and to reduce socio-economic vulnerabilities, or their irresponsibility, ignorance, and corruption83 (Supplementary Table 1). Disaster losses will continue to grow unless earthquake risks are substantially reduced, and societies become resilient.

The following challenging problems in seismic hazard and disaster science, yet to be resolved, can help in reducing disaster risks associated with earthquakes:

-

It is crucial to acquire a deep understanding of extreme seismicity by improving Earth observations and conducting thorough research utilising existing knowledge, models, observations, and advanced modelling techniques.

-

The development of comprehensive seismic hazard assessment tools is pivotal. Understanding the intricate interplay between earthquake hazards, exposure, and vulnerability110 is essential for the development of practical and effective models for risk assessment.

-

Reducing uncertainties in earthquake forecasting is important for enhancing the connection between the disaster mitigation community and the public.

-

Careful consideration should be given to the examination of cascading hazards associated with large earthquakes and to assessments of relevant risks.

-

As earthquakes cannot be prevented, a significant reduction in vulnerability to extreme seismic events is an important task. This can be accomplished by the regular surveillance of building and infrastructure conditions82 as well as by the monitoring of human systems at local, regional, and global levels with respect to demographic and economic shifts111. Emerging methodologies for data analysis, such as AI and machine learning approaches, will greatly assist in the field.

-

Interdisciplinary research related to seismic hazards and earthquake risk analyses as well as a transdisciplinary cooperation among stakeholders in DRR should be encouraged.

-

Less-affluent countries often lack the basic infrastructure, e.g. seismic instrumental networks, EEW systems, earthquake engineering regulations and communication networks112. Developing the infrastructure, reducing the differences among countries and regions, and enhancing earthquake resilience should be prioritised.

-

The enhancement of public awareness and capacity building about extreme seismic hazards and earthquake risks may be achieved via the utilisation of sophisticated risk communication skills. This can contribute to a substantial reduction in disaster risk.

Responses