Economic inequality is a crucial determinant of observed patterns of environmental migration

Introduction

The impacts of climate change and other environmental stresses on population migration have important implications for planning and have been identified as a potential link between climate change and conflict1,2,3. Migration is driven by complex interactions among multiple phenomena, so there is rarely a simple causal connection between climate change generally, or a single extreme event, and population movements3,4,5. Environmental migration may be considered as an example of a complex coupled human and natural system6, and understanding the dynamics and linkages in this system is important for planning adaptive responses to climate change and other environmental stresses.

Agent-based simulation models (ABMs) have been widely used to explore the dynamics and linkages between environmental change and migration7,8,9,10. ABMs are well-suited to these studies because they simulate human interaction with the environment while considering both individual and collective human behavior11. ABMs can account for emergent, non-intuitive patterns of collective behavior that arise from simple actions at the individual level. This makes ABMs useful tools for studying the dynamics of environmental migration and the links between environmental stress, individual decision-making, and large-scale migration outcomes7.

Recent ABM studies of both general and environmentally-driven migration have used a wide range of decision-making methods from simple stochastic processes to complex behavioral models informed by psychology7,8,10. This reflects the tension between simplicity and abstraction (“keep it simple stupid”, or KISS) versus complexity and detailed realism (“enhancing the realism of simulation”, or EROS)12,13. It is not always clear, especially when simulating human behavior, how much complexity is needed in a model.

Pattern-oriented approaches have proved valuable in ecological modeling and have potential to clarify the tradeoffs between complexity and simplicity14,15,16,17. In pattern-oriented modeling, multiple qualitative patterns are identified in empirical data and models are evaluated in terms of their ability to simultaneously reproduce the observed patterns. This approach can also provide sensitivity and uncertainty analysis for calibrating model parameters. Despite this potential, pattern-oriented modeling has not been widely applied to socio-environmental systems modeling18.

Bangladesh is widely considered to be one of the most vulnerable countries in the world to climate change because it has the greatest population density of any nation, apart from small city and island states, and a large fraction of that population lives on a low-elevation deltaic plain19,20. Many Bangladeshis live in rural agricultural communities, where their livelihoods are vulnerable to floods, droughts, and other hazards that threaten crops21,22. In Bangladesh, there is considerable interest in understanding the connections between environmental change and migration better, both to guide planning for adaptation to climate change23,24 and to potential future population changes25,26.

Bangladesh is located on the low-lying Ganges-Brahmaputra-Meghna (GBM) deltaic plain27. Most of Bangladesh occupies a low-elevation coastal zone, and is vulnerable to monsoon flooding, tropical cyclones, and sea level rise28. Additionally, both natural and anthropogenic environmental changes are contributing to shifts in livelihood activities21,22. In this complex socio-environmental system, frequent land ownership disputes are also a common challenge29,30.

In Bangladesh, migration is a common method of livelihood diversification and adaptation to environmental and economic stress31,32,33,34. Rural-to-urban migration is the most prevalent form35,36, and seasonal migration is common36,37. This distinctive combination of environmental vulnerability with established patterns of mobility, makes Bangladesh an ideal study site for modeling environmental migration dynamics in rural, primarily in coastal agricultural communities. It is unclear how climate change will affect these patterns in the future, and insights into the processes that produce these patterns will be valuable for adaptation planning.

Environmental shocks, such as droughts or heat-waves, that affect crop yields have much stronger influence than flood disasters on migration from rural communities in Bangladesh and Pakistan38,39. We developed an ABM to simulate the dynamics of migration from rural communities in Bangladesh in response to such environmental shocks. In the context of southwestern rural Bangladesh, this shock is most closely meant to represent a drought event. While ABM has not been widely used to study environmental migration in this context, two notable exceptions using very different decision-making methods yielded dramatically different results40,41. This points to a need to refine and validate ABMs of environmental migration in Bangladesh. To do so, we used a pattern-oriented approach in designing and assessing the model, both for validation of the model’s ability to reproduce observed patterns of migration, and for calibration and sensitivity analysis of model parameters15. Pattern-oriented modeling seeks to qualitatively reproduce multiple observed patterns that occur at different scales in the system of interest (e.g., individual versus collective levels), and analyze the sensitivity to parameter values of the model’s ability to reproduce those patterns. Ability to simultaneously reproduce observed patterns at multiple scales can be a powerful test for hypotheses14. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time that a pattern-oriented approach has been applied to an ABM of environmental migration. This contrasts with ecosystem modeling, where there is growing use of pattern-oriented approaches to study animal migration42,43,44,45. We represented decision-making by a simple economic heuristic of expected-utility maximization, but our flexible model structure will allow future research to compare different decision-making strategies. We used machine-learning methods to calibrate parameters, conduct sensitivity analysis, and evaluate how well the model reproduced the observed patterns.

We focused on two patterns reported by Gray and Mueller, in a highly cited study that uses longitudinal data covering a 15-year period from 1,700 households in rural communities across Bangladesh39. Gray and Mueller identified two unexpected patterns of internal migration from rural Bangladeshi villages after drought-induced crop failure:

-

Community pattern: As the proportion of a community impacted by environmental shock increases, rates of migration initially decrease below the baseline levels, but then increase, especially above a threshold where approximately 20% of the community is impacted. This shows that individual migration decisions are strongly influenced in a non-linear manner by community-level impacts.

-

Household pattern: Households that are directly impacted by environmental shock within the community are less likely to migrate. These households may find themselves trapped if they do environmental shocks and resulting economic losses leave them without the financial means to migrate.

These patterns are well-suited to ABM simulation because they connect phenomena at different scales, considering both household-level decisions (which households send migrants) and community-level effects (how the impact of drought on the entire community affects household-level decisions). An ABM that reproduces both patterns simultaneously can provide insight into mechanisms that couple the household and community scales.

Our model represents the decision to migrate as an economic one taken at the household level, maximizing the household’s expected utility, considering employment and other money-earning opportunities in the village, the earning opportunities in a destination, such as a city, and the cost of migrating. Coupling between the household and community scale is represented by a labor market, in which the impacts of drought affect labor supply (people seeking paid work) and demand (employment opportunities). When drought affects a few households’ farm plots, members can seek work on other households’ farms, but if many households are affected, fewer will hire workers, so people may leave the community to seek employment elsewhere.

Land ownership and the security of land tenure are known to affect vulnerability and resilience to climate change in rural agricultural communities, and the use of migration as an adaptation strategy46. Our model represents household land ownership using a Lomax (Pareto) distribution parameterized by a Gini coefficient. Our model experiments varied both the functional form of land distribution as well as the Gini coefficient. For each distribution of land ownership, we optimized two unknown parameters, representing the expected earnings of a migrant and the cost of migration, to simultaneously match the observed household and community patterns. Our results demonstrate that inequality in land ownership is critically important for capturing patterns of environmental migration in the study area.

Results

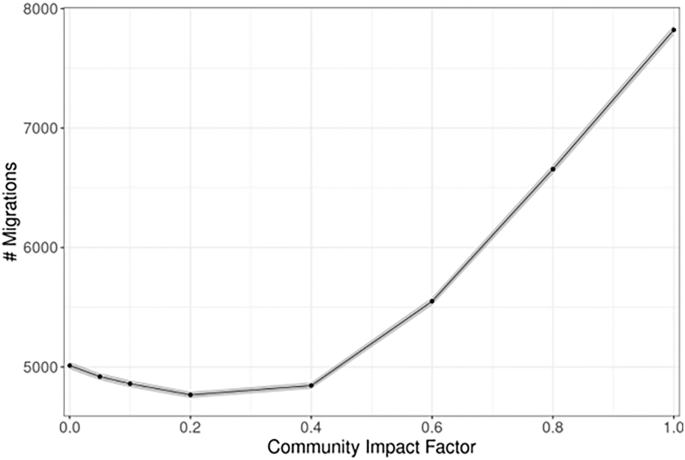

To assess the community pattern of interest, we measure how the total number of migrations varies for different levels of community impact. For each model run, we sampled household land ownership from a Lomax distribution with a Gini coefficient of 0.55, which we estimated from empirical survey data47. We sampled 150 pairs of the two unknown parameters, representing the cost and utility of migration, and for each of these pairs, we ran 100 simulations for each community impact factor (a total of 15,000 runs for each community impact factor). The simulations satisfied both patterns simultaneously for 137 of the 150 pairs of parameter values. For these 137 samples, the model runs cleanly match the community pattern, in which migration drops as the community impact factor rises from 0 to 0.2, and then rises for larger impact factors (Fig. 1).

Model results of number of migrations in the community by varying levels of community impact. The black lines represent the mean of 13,700 model runs for each community impact factor. The gray band represents the 95% confidence interval for the mean.

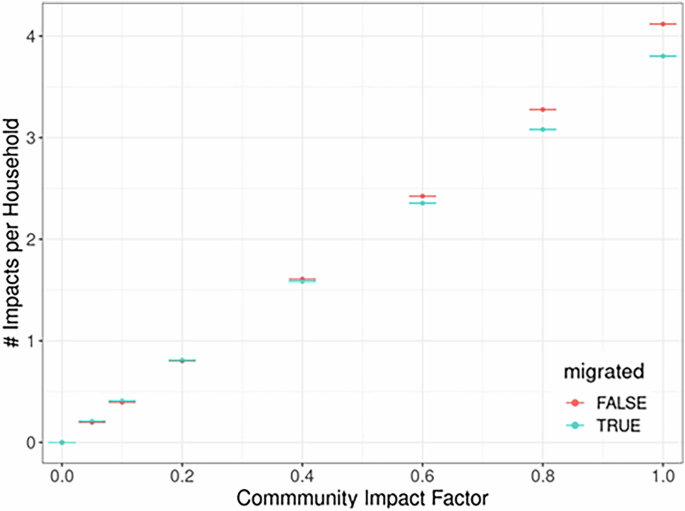

To assess the household pattern, we compare the number of environmental shocks experienced by households that migrated during the simulation versus those that never migrated (Fig. 2). The observed household pattern was that non-migratory households were impacted more frequently by environmental shocks than migratory households. This pattern is clearly reproduced for community impact factors about 0.4 in Fig. 2, which represents the same simulation runs used in Fig. 1.

Households are grouped into those that have migrated (blue) and those that have not (red). The mean number of times households in each group were impacted directly by an environmental shock across all trials is plotted, with error bars indicating 95% confidence intervals of the mean (across 13,700 model runs at each community impact factor). For community impact factors above 0.4, Pattern 2 is reproduced: non-migratory households were impacted by more environmental shocks than migratory households were.

Assessing successful parameter space

Results reported thus far have included only the results from parameter combinations that, when implemented in the model, were successfully able to reproduce both patterns of migration. To identify these successful parameter combinations of the 150 combinations tested, we aggregate the results of all the runs at each combination and evaluate them against our community pattern and household pattern criteria. If a parameter combination is able to reproduce both patterns simultaneously (evaluated by averaging outcome variables across all 100 runs), then it is counted as a “success”. We then use our machine-learning approach previously described to evaluate the parameter space.

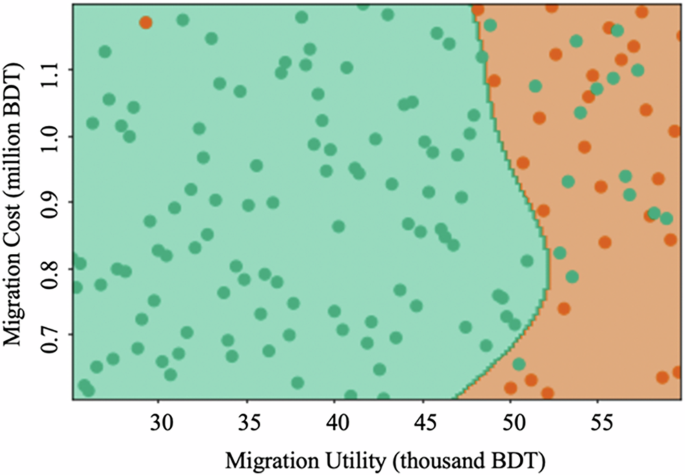

Cost of migration and utility of migration (both in Bangladesh Taka, BDT) are uncertain parameters that require calibration for the utility maximization decision method. For utility maximization with a Gini coefficient of 0.55, 137 of the 150 parameter combinations (91%) were able to successfully reproduce our patterns of interest. Results of the SVM predicted parameter space are shown in Fig. 3. These results highlight that the model is largely insensitive to the cost of migration within this range of parameters and above a cost of approximately 0.2 million BDT, around $1800, while the migration utility is successfully able to reliably reproduce the patterns of interest only below approximately 50,000 BDT, around $460 per year (Fig. 3).

Parameter combinations of migration utility and migration threshold with a utility maximization decision method and SVM predicted successes of the parameter space for both patterns of interest. Points show parameter combinations sampled in the numerical experiments with green points indicating successful pattern replications and orange points indicating failed pattern replications. Colors show SVM predictions where green represents predicted success and orange represents failure.

A strength of pattern-oriented modeling is that sensitivity analysis of parameter calibration can reveal which characteristics of the model dynamics are due to the structure of the model and which arise from specific parameter values14,48. The lack of sensitivity to the unknown parameters for the cost and benefits of migration suggests that the patterns observed by Gray and Mueller arise from the basic structure of our model, and that overfitting of these two parameters is not a concern.

Importance of land distribution

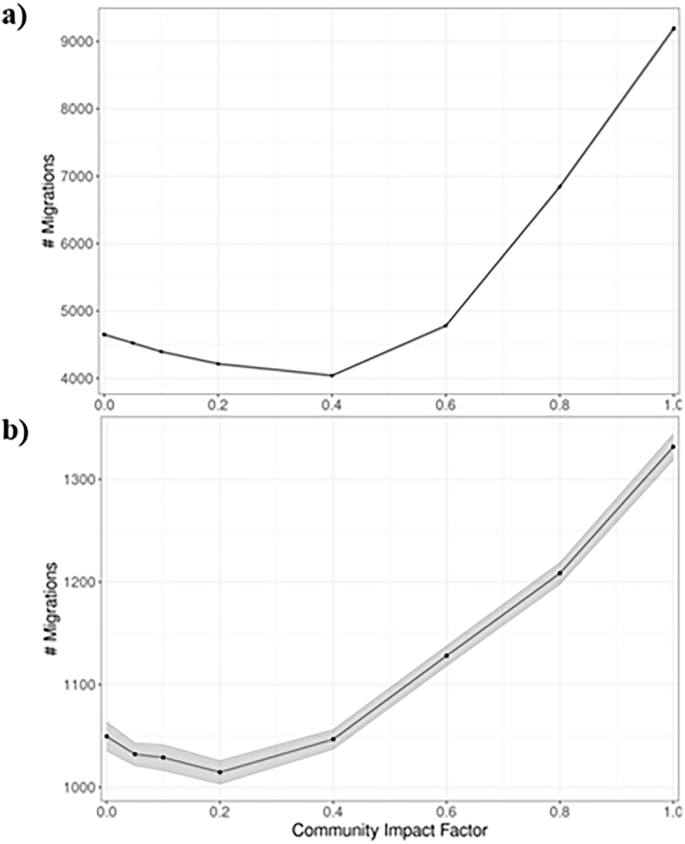

As a sensitivity on the value of Gini coefficient of land distribution, we repeated the model experiments for a Gini coefficient of 0.25 and 0.75 and compared to the baseline coefficient of 0.55. With the utility maximization method, a Gini coefficient of 0.25, representing less inequality in land distribution, was only able to reproduce our patterns of interest across 73 (49%) of the 150 parameter combinations (Supplementary Fig. 1), while a Gini coefficient of 0.75 succeeded for 119 (79%) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, the shape of migrations across levels of community impact factor is affected by the Gini coefficient: For a Gini coefficient of 0.25 the number of migrations is comparable to the baseline, but the threshold for increasing migrations occurs at a community impact factor of 0.4 instead of 0.2 (Fig. 4). For a Gini coefficient of 0.75, the threshold remains at 0.2, but the total number of migrations is much smaller than for the baseline. In a previous paper, we also tested the model using a lognormal distribution of land ownership instead of a Lomax distribution, and a success rate of just 1 of the 150 parameter combinations (0.67%)49. Thus, both the shape of the distribution of land ownership (i.e., the distributional form used) and the degree of inequality matter for reproducing the patterns of interest. The fact that the model qualitatively reproduces the observed patterns over a broad range of Gini coefficients suggests that these patterns arise from the basic structure of the model, and reduces concern about overfitting, while the fact that the model best reproduces the details of the observed patterns at Gini coefficients equal to or greater than the empirically observed value suggests that changing the degree of inequality can affect the detailed dynamics of environmentally driven migration.

Model results based on utility maximization decision method of number of migrations in the community by varying levels of community impact and for a Gini coefficient on land distribution of 0.25 (a) and 0.75 (b). The black lines represent the mean of all trials. The gray band represents the 95% confidence interval for the mean.

Discussion

In this work, we present results of an original ABM of environmental migration dynamics in rural Bangladesh. Our model incorporates individual agents, households, and livelihood opportunities within a stylized agricultural community. Importantly, our model also presents, to the best of our knowledge, the first time that a pattern-oriented approach has been used to model environmental migration.

For our community-level pattern of interest, we see that a utility maximization decision heuristic robustly reproduces both observed patterns of migration, including the nonlinear aspects of the community pattern. We also find that the threshold of community impact at which migration begins to rise in the testing of the community pattern occurs at approximately 20% (0.2), in the simulation, as it does in the observed pattern (Fig. 1), although this quantitative agreement might well be coincidence. The household-level pattern in which households that are impacted directly by an environmental shock are less likely to migrate is also reproduced for community impact above 40% (Fig. 2). Our model satisfied both patterns simultaneously for 91% of the 150 unique combinations we tested of the migration cost and migration utility parameters. Evaluation of the parameter space using a radial SVM method shows that within our sampled parameter space, as long as the one-time migration cost is greater than 200,000 BDT ($1700 US) and the annual benefit is less than 50,000 BDT ($425 US) the model is fairly insensitive to both parameters (Fig. 3). We recognize that this cost of migration is very high compared to the wealth and income of a typical rural household. One possible explanation is that the cost of migrating may incorporate non-monetary (hedonic) costs of migration, in addition to the monetary costs. These hedonic costs could include such considerations as the pain of leaving one’s home, family, and community. Empirical studies of migration in Bangladesh have found that migration can be costly in terms of both monetary costs and non-monetary disutility36,50.

After the initial evaluation using an empirical land distribution derived from survey data, we used the model to evaluate the influence of inequality in land ownership upon migration by re-running the analysis with varying levels of inequality and an alternate distribution function. Both the shape of the distribution (Lomax versus log-normal) and the degree of inequality used to parameterize the distribution affected how well the simulation results matched the observed patterns. When the inequality was equal to or greater than that observed in our survey data, the model maintained a high rate of successful pattern reproduction, although the threshold of community impact at which migration increased changed. When the inequality was less than the observed value, the model was much less successful at matching observed patterns, and the model was almost completely incapable of reproducing the patterns with a log-normal distribution of land ownership.

This unexpected finding highlights the important influence of economic inequality on patterns of migration following environmental shocks, which we were only able to learn through our model and pattern-oriented approach. Previous work has suggested that climate change and migration will contribute to more severe inequality51, but, here, we show that community-level inequality is important for influencing patterns of climate-related migration themselves. This is broadly consistent with empirical work in the context of Bangladesh that has shown that wealth may have a u-shaped relationship with migration, with the lowest income and highest income houses both being more likely to migrate as a result of a climate shock52. What we are able to demonstrate with our model, beyond Wiig et al.’s findings52, is that levels of inequality are important for community-level patterns of migration, not just individual migration.

A simple model of expected-utility maximization, with minimal assumptions, was able to robustly reproduce observed patterns of migration, but only when inequality was captured correctly. The model’s performance was very sensitive to inequality of land ownership, but not to the exact cost and utility of migration. With our model, we found that inequality in immobile assets (land ownership) was especially important, rather than inequality in income. The insensitivity of our model results to the cost and utility of migration suggests that the phenomena that produce the observed patterns of migration in rural Bangladesh are captured in the model’s structure in which households make migration decisions to maximize expected utility in the context of a dynamic local labor market. Future work could further consider how inequality in different kinds of assets, beyond land ownership, may or may not influence migration. Additional future work could explore model sensitivity to additional factors such as network effects, labor market conditions, varying environmental shocks, and more complex decision-making methods.

Individual migration decisions are deeply personal and undoubtedly involve more than purely economic calculations (including the importance of gender, social networks, and norms in influencing those decisions7,53,54), and our model’s flexible representation of decision-making will facilitate future investigations of such factors; but, in this context, an economic model can capture enough of the decision-making processes to reproduce observed patterns. This is consistent with recent empirical work in the region, which suggests that “climate migration” in Bangladesh is primarily an economic decision and environmental pressures are secondary55.

Our results reveal that, in this context, inequality in land ownership is a key driver of overarching migration dynamics, suggesting that environmental migration research should pay close attention to the role of internal socioeconomic dynamics in a place, rather than focusing primarily on external environmental or climatic pressures. This insight can enable the development of more nuanced policies to address the root causes of migration, such as improving access to education, healthcare, and livelihoods for marginalized groups while promoting equitable growth. Thus, our results can help policymakers in designing targeted, equity-focused interventions that strengthen social cohesion and reduce migration pressures. Our results are also important for policy given the large number of land-disputes in Bangladesh’s legal and socio-economic landscape29,30. The demonstrated connection with migration draws further attention to the need for land-rights policy reformation. Such policy may open pathways for more sustainable and inclusive climate adaptation strategies if land related problems can be addressed. Moreover, centering equity also opens pathways for more sustainable and inclusive climate policy, ensuring that development policies address both the symptoms and cultural causes of migration. Such policies could align with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), namely SDG 10 (Reduce Inequalities) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), offering opportunity for a comprehensive approach to tackle interconnected challenges in coastal Bangladesh.

As mentioned, previous empirical and theoretical work has identified household wealth as an important factor influencing a household’s ability to afford to send a migrant and ability to adapt in place after environmental change53,56. We find that inequality across the community, not just individual household wealth, has an important effect on migration decisions. This could have useful applications in policymaking to enhance community resilience i.e. development organizations, advocacy groups, and local stakeholders can leverage these insights to foster community-led initiatives that address inequality. The findings also resonate in global policy arenas, informing strategies for managing migration pressures in other inequality-prone regions57. This finding may also direct future empirical work to investigate interactions between inequality and migration. Finally, while this study investigated an expected-utility maximizing decision process, our model has a flexible structure that will make it easy to substitute other, more psychologically complex decision models, and compare their performance to the economic one.

Methods

Agent-based model structure and scheduling

Our ABM, which was first presented in Best et al., uses a multi-scalar approach to simulating environmental migration by incorporating agents with characteristics and decision-making at the individual, household, and community level within a stylized origin community49. The model is constructed to simulate migration decisions at the household level under varying levels of community-level environmental stress and is designed to investigate dynamics of migration, livelihood opportunities within a community, and environmental stress. We provide a detailed description of the model based on the Overview, Design concepts, and Details (ODD) protocol (Supplementary Methods)58. We also provide our full model code, which is implemented in Python.

While the model is not explicitly spatial in nature, the virtual environment consists of entities across scales. Each time step of the model simulates one year of time. Entities representing individuals, households, and the overall community are incorporated, and each type of entity has specified attributes and behaviors.

Individuals are primarily defined by attributes of gender, age, employment at each step of the model, wages, and status as a migrant or not. Each individual is assigned to a household, which is specified by the individuals it contains, land owned, and total wealth. Each household entity also has a defined head of household. The household head is defined as either the oldest adult male individual within the household or, if no male members are present, the oldest adult female member. As the primary economic and decision-making unit within the model, households also keep track of wealth at each step of the model. Households who own land may also hire individuals from other households and keep track of their employees, payments, and expenses. In this way, the economic accounting of the model takes place at the household level. At the next level up in scale, each household belongs to a stylized origin community. The community contains a certain amount of total land distributed across the households, as well as livelihood opportunities in agriculture and both skilled and un-skilled non-agricultural employment options. The community of the model is also the level at which environmental shocks may occur within the environment. At each time step, an “environmental shock” may occur stochastically. If an environmental shock occurs, a specified fraction of the households within the community are chosen at random and subjected to a and loss of crops and agricultural income.

Each model simulation begins by initializing the population of individuals, households, and the community. Importantly, the distribution of land ownership within the community is parameterized as a Lomax distribution, as a Lomax distribution fits the survey data well and has widely proved useful for describing observed distributions of wealth and income59. The Lomax distribution characterizes inequality using a single parameter ((alpha)), which is related to the Gini coefficient (Eq. (1))60:

We calculated (alpha) from a Gini coefficient of 0.55, which we derived from Carrico and Donato’s surveys of rural households47. For comparison, the national-level Gini index for Bangladeshi income is 0.32, so land-ownership in our study area is distributed far more unequally than income is for the country as a whole61. Our model assumes that the number of agricultural jobs is proportional to agricultural land holdings and rounds to zero below a threshold, so livelihood opportunities are limited by the number of households that own large amounts of land.

At the beginning of every time step, which represents one year of time, the community faces a stochastic risk of experiencing an environmental shock based on a pre-defined probability. In this case, the annual probability of an environmental shock is set to 0.2. If the environmental shock takes place, a specified fraction of households in the community will be directly impacted, resulting in loss of crop yields and the associated income on any land owned.

Next, individuals assess employment opportunities within the community. These individuals may find opportunities in agriculture (on their own land or on another household’s land) or non-agricultural jobs (either unskilled and lower paying or skilled and higher paying). Only individuals who belong to households with a sufficiently large amount of land may work on their own agricultural land. These households with large amounts of land may also elect to hire outside employment to help. In this case, households that are looking to hire agricultural labor may enter an internal labor market. Individuals who are looking for employment may also enter this labor market and attempt to be “hired” by a searching household. The labor market uses a simultaneous double auction approach to match job seekers with possible employers based on what salary individuals are willing to accept and what households are willing to pay. At the end of the double auction, some individuals may be left without employment in either agriculture or non-agriculture.

Once all individuals have found or attempted to find employment, each household conducts a calculation of its expected income, based on its members’ expected wages from employment, and crops grown on its land. The household then uses the specified decision-making method to decide whether to send an individual as a migrant. Each household has a DecisionMethod object (Supplementary Methods), which provides a function that implements the decision. In this work the decision model used an expected-utility maximization approach, but the model allows for easy substitution of other decision methods in future work. If a household sends a migrant, that individual no longer participates in the model activities within the community (i.e., raising crops and searching for employment), but contributes to the household’s income by adding remittances at each time step, the value of which is determined by the migration benefit parameter (in BDT).

At the end of each step, every household updates its wealth by summing individual wages, subtracting expenses and payments to employees, and adding income from crops grown on the household’s land, if it was not impacted by an environmental shock in that time step. Each individual ages by one year and the time-step ends. At the end of each time step, the model records household migrations, wealth, and employment. This process repeats for a specified number of steps (years). Data from two primary social surveys from southwestern Bangladesh was used to parameterize many of the variables to be initialized within the model, as described in Best et al.47,62,63,64.

Decision-making

We designed our ABM to facilitate adding multiple decision strategies and specifying them at run-time. Here, we focus on a simple economic method of migration decision-making, but the model allows for future research to easily substitute alternate decision strategies, such as psychological theories. Our economic decision model serves as a baseline for assessing whether such a simple expected-utility maximization heuristic can reproduce observed migration patterns. A household will send a migrant if the decision is economically beneficial when comparing the cost of migration and the migrant’s expected income to what they could earn in the home village. The household first selects one member who is eligible to migrate (males older than 14 years). The household then compares the cost of the trip and the migrant’s expected income at the destination to what they could earn within the community. If migration will increase household economic utility (expected wealth) and the household has sufficient funds to meet the cost of sending a migrant, then that individual will successfully “migrate” from the origin community. After a successful migration decision, a household subtracts the cost of migration from its wealth.

Machine learning for model calibration

We parameterized key model parameters based on available data, following procedures described by Best et al.49. However, we were unable to find data to estimate the costs and benefits of migration. We combined machine learning with pattern-oriented modeling to calibrate these uncertain parameters and identify a parameter space over which we expect our model to successfully reproduce our two patterns of interest49.

We use Latin hypercube sampling to select 150 unique combinations of the cost and the utility of migration across the uncertain parameter space65,66,67. We then conducted ABM simulations for each sampled combination of parameters, running the model 100 times for each of 8 values of the community impact factor, from 0 to 1 (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8, and 1). We then assessed what fraction of the simulations matched the community and household patterns. The criteria for matching the community pattern are that there is a community impact factor for which the average number of migrations, over the 100 simulations for that combination of parameters and impact factor, is less than for a community impact of 0, and there is a threshold community impact above which the average number of migrations is greater than for an impact of 0. This definition captures the initial decline followed by an increase in migrations as the level of community impacted by the environmental shock increases. The criterion for matching Pattern 2 is that on average, non-migratory households are directly affected by more environmental shocks than migratory households.

We assigned a binary condition of success or failure to each parameter combination according to its success in reproducing both patterns. We then used a support vector machine model (SVM) with a radial kernel to predict a region of parameter space within which the model will successfully reproduce both observed migration patterns.

Responses