EEG-based headset sleep wearable devices

Introduction

Sleep plays a crucial role in overall health and well-being, and its quality is strongly linked to numerous health issues, as well as mental health and cognitive performance1,2. Polysomnography (PSG) has been the gold standard for clinical sleep monitoring and diagnostics, capturing a variety of physiological responses, including electroencephalogram (EEG), electrooculogram (EOG), and electromyogram (EMG) activity, as well as breathing effort, airflow, pulse, and blood oxygen saturation3. Despite PSG’s reliability in recording sleep patterns, it has several limitations. PSG studies are expensive and time-consuming, requiring trained professionals for setup and data scoring. Sleep stages (wake, sleep stages 1 (N1), 2 (N2), 3 (N3), and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep) are manually annotated by experts in 30-second epochs according to the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s guidelines3. N1 and N2 stages are often combined as light sleep, and N3 is referred to as deep sleep. This manual scoring suffers from low inter-rater reliability, with an average agreement of 82.6%4 or κ = 0.765, decreasing even further in patients with sleep pathologies4. The stage-specific agreement has shown to be even lower, with N1 demonstrating only fair agreement between scorers (κ = 0.24)5. Furthermore, PSG may not accurately represent a patient’s typical sleep. The unfamiliar clinical settings can cause stress, and one-night recordings do not account for intra-individual night-to-night variabilities.

Wearables and nearables are increasingly being used for sleep monitoring6,7,8,9,10,11. While nearables offer non-contact methods to monitor sleep, wearables provide more detailed and accurate sleep data12. Unlike other sleep-monitoring wearbles, EEG-based devices closely mimic the EEG component of PSG, making them highly relevant for precise sleep monitoring. In the past decade, advancements in wearable technologies have given rise to new types of sleep staging devices that use forehead, ear, or neck electrodes to acquire EEG data. These user-friendly and cost-effective devices can potentially offer a viable alternative to PSG, facilitating long-term, home-based sleep monitoring without the need for expert oversight. However, their integration into clinical practice is still in its infancy, largely due to the limited evidence of validations against PSG, regulatory constraints, data privacy and security concerns, and usability and availability issues.

While previous reviews6,7,8,9,10,11 have provided comprehensive overviews of wearable sensors in sleep monitoring, they typically cover a broad range of devices, including wrist-worn, ring-based, and other non-EEG-based wearables. However, these reviews often only touch upon EEG-based devices as part of a larger discussion. This review differentiates itself by specifically focusing on EEG-based wearable sleep monitoring devices, delving deeper into their unique challenges and advantages. We provide a detailed examination of validation studies, regulatory considerations, and specific applications of EEG-based devices in both clinical and healthy populations. Additionally, this review highlights distinct issues related to data privacy and security, usability, and the challenges hindering their wide adoption in clinical practice, along with potential strategies to mitigate these obstacles. By narrowing our focus to EEG-based devices, we aim to provide a more targeted analysis that can better inform the development, adoption, and future direction of these specific technologies in sleep monitoring.

EEG-based wearable sleep tracking devices

The performance of EEG-based sleep tracking devices is often evaluated using Cohen’s kappa (κ) values, which measure the agreement between two hypnograms (e.g., specialist vs. device) while accounting for agreements that occur by chance. It is calculated as κ = (pj–pe)/(1-pe), where pj is the scorer accuracy, and pe is the baseline accuracy. Kappa values less than 0.00 indicate poor agreement, 0.00–0.20 slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement, and over 0.80 excellent agreement13. While devices’ overall performance and agreement with the gold standard are often reported using Cohen’s kappa and/or accuracies, the evaluation of sleep-stage-specific performance frequently relies on sensitivity and specificity metrics, as they provide a clearer understanding of the device’s ability to detect specific sleep stages14.

Forehead

Wearable EEG-based devices utilizing forehead electrodes have demonstrated varying degrees of success in sleep staging and monitoring. A common type of wearable EEG measurement device is a headband, with which electrodes are primarily placed on hair-free facial locations to ensure optimal contact and signal quality. Headbands such as Zeo have shown moderate agreement with PSG (κ = 0.56) but face challenges in detecting wakefulness and have lower performance in low sleep efficiency sleep15,16,17. The Dreem headband has shown good similarity with PSG (κ = 0.75)18. In addition to sleep staging, the Dreem headband has been used to measure sleep position19 and apnea events20, expanding its utility in sleep monitoring. Sleep Profiler (κ = 0.63 to 0.65) and Cognionics (accuracy = 74%) headbands have also demonstrated moderate agreement with PSG but had low agreement (κ = 0.07) and sensitivities for the N1 stage (sensitivity = 0.27–0.32)21,22,23,24. Sleep Profiler is also used to measure arousals25, sleep position26 and sleep spindles27. Other types of devices utilizing forehead and EOG electrodes include sleep masks, which have demonstrated substantial agreement with PSG (κ = 0.77 and κ = 0.79) but also face limitations in accurately measuring N128,29. The Sleepscope device has been utilized not only for sleep staging, where it demonstrated a substantial agreement with PSG (κ = 0.75), but also for measuring arousals30. Neury, a prototype bipolar EEG device, has been used for spike quantification, providing insights into sleep microstructure31. Devices using thin, comfortable, cost-effective electrode sheets while ensuring data quality can offer a comfortable alternative to the existing headband and sleep-mask-type devices. Such devices have shown substantial agreement with PSG (κ = 0.72 and κ = 0.70)32,33. Another type of device, the SOMNOwatch Plus EEG, combines actigraphy with EEG. In healthy adults, the device showed a high agreement (κ = 0.78) with PSG when using semiautomatic sleep analysis (Somnolyzer 24×7), while its software DOMINO Light only showed fair agreement with PSG (κ = 0.37)34. In sleep apnea patients, SOMNOwatch Plus EEG showed high agreement with PSG (agreement = 74.2%), and combining EEG with EOG/EMG improved the results (agreement = 75.5%)35.

Ear

Ear EEG devices have emerged as a promising alternative for sleep monitoring, demonstrating good agreement with PSG and potential applications in various settings. Both in-lab and home monitoring studies have consistently shown that such devices can be used for automatic sleep staging (substantial agreement with PSG, κ = 0.61–0.74)36,37,38,39,40,41,42, longitudinal monitoring39, sleep spindle detection43, muscle activity detection44, and drowsiness monitoring45,46. Devices using around-the-ear electrodes, like the cEEGrid, have shown moderate to substantial agreement with PSG (κ = 0.42 to 0.67)47,48,49, which increased with the addition of EOG and EMG electrodes (κ = 0.70)50. Self-application of these devices has been proven feasible for healthy participants, enabling self-recording of EEG at home50,51. However, like devices utilizing forehead electrodes, ear EEG devices face challenges in detecting the N1 stage36,37,38,39,40,41,42,47,48,49,50.

Neck

The Zmachine Insight+ sleep monitoring system uses electrodes placed on the neck and derives data from the differential mastoids (A1-A2). The system has demonstrated excellent agreement with PSG (κ = 0.85)52 for sleep-wake detection and substantial agreement (κ = 0.72) for staging wake, light, deep, and REM sleep53.

In this review, we examine 32 studies utilizing EEG-based wearable sleep monitoring devices in clinical (n = 20) and healthy populations (n = 12). Most of these studies (n = 21) used forehead devices. Overall, Sleep Profiler, Zmachine Insight+, and Dreem were the most used devices in the analyzed studies. An overview of the devices is provided in Table 1.

Wearable EEG-based sleep-tracking devices in clinical and healthy populations

This section explores the applications of wearable EEG-based sleep-tracking devices in both clinical and healthy populations. The studies include comparisons of sleep patterns between healthy individuals and those with clinical conditions, analyses of intervention effects on sleep, performance comparisons with gold-standard methods, and investigations of the relationships between sleep and various aspects of daily life. Tables 2 and 3 summarize these applications, highlighting the effectiveness and potential benefits of these devices in diverse settings.

Clinical populations

Neurodegenerative diseases

EEG-based wearables have provided valuable insights into critical sleep differences between neurodegenerative disease (NDD) patients and healthy controls, such as reduced slow wave sleep in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) patients54 and NREM (non-REM) slow wave activity as an early biomarker for identifying individuals at risk for AD25. Additionally, these devices highlighted that agreement levels between Zmachine Insight+, actigraphy, and sleep diaries were shown to decrease in AD patients, highlighting that sleep diaries may capture different aspects of sleep compared to wearable EEG devices55. For Parkinsonian spectrum disorder (PSD) patients, EEG wearables have shown comparable results to PSG56, suggesting their potential in tracking disease progression through biomarkers like NREM sleep with hypertonia27. In multiple sclerosis (MS) patients, a correlation between physical activity and increased deep sleep was revealed57. Furthermore, supine sleep was found to be more prevalent in NDD patients than in healthy controls26. These findings align with broader research indicating that sleep disorders are observed in over 60% of patients with NDDs like PSD, AD, and MS58,59,60,61,62,63. Addressing sleep disorders could potentially delay or prevent the development of cognitive impairments, yet the relationship between sleep disturbances and NDDs remains unclear64. Overall, EEG-based wearables can provide critical insights into this relationship and guide the development of targeted interventions for NDD patients.

Neurological and psychiatric disorders

Wearable EEG-based devices have shown promising results in monitoring sleep and responses to therapy in epilepsy patients. Ear EEG has demonstrated effectiveness in detecting seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy patients and provided moderately high agreement with scalp EEG for sleep staging38,65. In pediatric epilepsy patients with continuous spike-wave of sleep, these devices can provide accurate quantification of spike activity and have been used to monitor responses to corticosteroids, sulthiame, and ketogenic diets31. These findings are consistent with broader research indicating that sleep and epilepsy share a complex bidirectional relationship, where on one hand, seizures and anti-epileptic drugs have found to impact sleep, and on the other hand, sleep pattern changes, such as increased wake after sleep onset, decreased REM, disruptions in the stability of NREM sleep, and sleep oscillations, have been linked to epilepsy66. Sleep disturbances, such as insomnia, poor sleep quality and nightmares, are also prevalent in psychiatric disorders and are associated with the severity of psychiatric symptoms67,68,69. Monitoring sleep in this patient group using Zmachine Insight+ showed fair to good agreement with PSG for most sleep metrics70, suggesting that wearable EEG-based devices could be effectively used for longitudinal monitoring. This could facilitate the development of targeted interventions to improve sleep quality and overall well-being in psychiatric patients.

Chronic pain

EEG-based wearables like the Dreem headband have shown potential for monitoring sleep in chronic pain patients, as preliminary findings indicate patient satisfaction with the device, suggesting its future utility in clinical practice71. Despite the prevalence of sleep problems among this population and their role in developing and maintaining chronic pain, they are often overlooked in routine care72,73. Integrating wearable EEG-based devices could help better understand and address sleep-related issues in chronic pain management.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Wearable EEG devices have provided valuable insights into sleep disturbances experienced by individuals with PTSD. For instance, data collected using the Cognionics device revealed that PTSD patients have less REM and Lo Deep sleep (0.1–1 Hz) and more Hi Deep sleep (1–3 Hz) compared to controls74. Additionally, the impact of medications on sleep efficiency and fragmentation was demonstrated in another study using the Cognionics device, with melatonin being associated with more Lo Deep sleep, indicating its potential effectiveness in treating PTSD-related sleep problems75. These findings align with broader research indicating that over 92% of individuals with PTSD report sleep disturbances, including insomnia and nightmares, which significantly impact their overall functioning and quality of life76,77,78.

Diabetes

Wearable EEG-based devices have highlighted significant associations between sleep quality and glycemic variability in diabetes patients. For instance, a study using Zmachine Insight+ showed that poor sleep quality was associated with increased glycemic variability in type 1 diabetes patients, emphasizing the need to consider sleep quality in personalized diabetes management plans79. This aligns with broader research demonstrating sleep disturbances in this population and the relationship between poor sleep quality and lowered glycemic control in both, type 1 and 2 diabetes patients80,81. Using wearable EEG-based devices for home monitoring may provide a feasible way to optimize blood glucose control in diabetes patients.

Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and surgical patients

EEG-based wearables have provided critical insights into sleep disturbances in ICU and surgical patients, highlighting the impact of these disturbances on patient outcomes. Using the Sleep Profiler, Jean et al. examined sleep architecture in critically ill patients, demonstrating how intubation and sedation methods affect sleep quality82. This aligns with broader research indicating that sleep deprivation in ICU patients is linked to delirium, prolonged mechanical ventilation, increased mortality, and extended ICU stays83,84,85. Another study found the potential benefits of dexmedetomidine sedation on sleep duration in non-intubated ICU patients86. In geriatric cardiac surgical patients, the Dreem headband was utilized for peri- and postoperative sleep analysis, revealing increased light sleep and decreased deep sleep in the postoperative phase87. Overall, using EEG-based devices can enhance the management of sleep disturbances and improve outcomes in ICU and surgical settings.

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) and Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

Wearable EEG-based sleep trackers have facilitated the investigation of sleep impairments in both OUD and AUD patients. For instance, gender-based differences and discrepancies between objective and self-reported sleep metrics were noted in individuals with OUD undergoing methadone vs. buprenorphine treatment, while no differences between the treatment groups were found88. In another study, further discrepancies between EEG-based and self-reported sleep metrics, along with associations between withdrawal severity and alterations in sleep metrics, were found89. A study in individuals with AUD found lower cortical thickness in the right and left hemispheres to be associated with shorter N3 and REM sleep stage durations, respectively, indicating that addressing brain structural changes could positively impact sleep and vice versa90. These findings are consistent with broader research showing that sleep impairments are a common comorbidity in OUD and AUD patients91, underscoring the potential of wearable EEG-based devices to improve the management of sleep disturbances in these populations.

Sleep disorders

EEG-based sleep wearables have demonstrated potential in detecting and monitoring sleep disorders. The Dreem2 headband accurately detects OSA with performance comparable to expert PSG scorers, making it suitable for at-home monitoring20. The Sleep Profiler is effective in diagnosing sleep bruxism92 and identifying biomarkers for non-REM hypertonia and REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), aiding early diagnosis of neurodegenerative conditions93. These findings are particularly relevant given the established links between sleep disturbances, including OSA and central sleep apnea, and severe cardiovascular issues such as hypertension, stroke, arrhythmias, coronary artery disease, and heart failure94,95,96. The relationship between sleep disturbances and cardiovascular diseases highlights the potential of sleep monitoring wearables to provide critical insights and enable timely, effective interventions.

Healthy populations

Diet, stress, and chemosensory function

Wearable EEG-based sleep monitoring devices have demonstrated the short-term impacts of sleep fluctuations on daily life and well-being. Studies in non-obese participants revealed associations between sleep duration and chemosensory function, with longer sleep being correlated with lower sweet taste preference and better odor identification97,98. Additionally, one night of reduced sleep in non-obese women was linked to increased hunger, tiredness, sleepiness, and food cravings99. These findings align with broader research indicating that poor sleep quality is associated with poor dietary habits, including higher intake of fats and carbohydrates, which can exacerbate sleep disturbances100,101. Furthermore, the EEG-based wearables have shown that changes in sleep measurements can predict next-day stress levels102 and changes in emotional status30, supporting the connection between poor sleep quality and heightened stress levels highlighted in the broader literature103,104,105. Overall, these insights underscore the potential of wearable EEG-based devices to enhance our understanding of the interplay between sleep, diet, and stress, suggesting that improving sleep quality could positively impact dietary habits and stress levels.

Sports and exercise

EEG-based sleep monitoring devices have shown promise in sports science research, providing valuable insights into the relationship between exercise, sleep, and neurocognitive health. Although such devices cannot fully replace PSG, they can be feasible for monitoring and detecting sleep disorders in athletes42. A study investigating the effects of exercise on sleep in older adults found increased deep sleep, decreased REM sleep, and increased total EEG power in light and deep sleep following a 12-week aerobic exercise intervention106. These findings support broader research indicating that good sleep quality, which can be enhanced by moderate-intensity aerobic exercise, particularly in older adults107, is crucial for overall health and athletic performance108,109,110.

Changes in daily routine

Wearable EEG-based sleep monitoring devices have been used to study the effects of changes in daily routines and work schedules on sleep. For instance, data collected using the Dreem headband demonstrated alterations in objective sleep measures during COVID-19 lockdowns in France. The largest changes were found in “night owls” whose REM sleep had significantly increased111. Another study used Zmachine Insight+ to monitor night shifts’ effects on anesthesia residents’ sleep and demonstrated that a three-day recovery period is not sufficient for restoring sleep levels after night shifts112.

Improving sleep

EEG-based wearable devices have demonstrated potential in improving sleep quality and reducing sleep disturbances. For example, the Dreem headband has been shown to be feasible for delivering auditory stimulation during N3 sleep to enhance slow oscillations and improve sleep quality113. Additionally, it has been used to administer acoustic simulations during sleep apnea events to reduce apnea event duration and oxygen desaturation amplitude and duration114. iSleep, an EEG- and audio-based sleep enhancement device, significantly reduced time-to-sleep for individuals with difficulty falling asleep115. Furthermore, a randomized controlled trial demonstrated that providing feedback and guidance on sleep perceptions using wearable devices like Fitbit and EEG headbands can reduce insomnia severity and sleep disturbance, though it did not alter sleep-wake state discrepancies significantly116.

Discussion

Challenges

Wearable EEG-based devices for sleep staging have emerged as a promising solution to enable data-driven approaches in healthcare, promoting personalized and preventive medicine. However, their widespread adoption in clinical practice faces several technical and ethical challenges. Collaboration between various stakeholders, including technology experts, medical professionals, and regulatory bodies, is essential to overcome these barriers.

Accuracy and validation

Demonstrating clinical validity is crucial for the adoption of wearable EEG-based devices. Recent guidelines by Menghini et al. emphasize the importance of epoch-by-epoch evaluation when validating sleep trackers against gold standard PSG, which should be considered for accurate validation of new devices14. Even studies achieving the highest accuracies18,38,53 have exhibited lower agreeability measures with PSG than inter-scorer reliability in PSG-based approaches (κ = 0.76)117, likely due to a lower signal-to-noise ratio in wearables. Manual scoring can improve agreement with PSG data; for instance, Sleep Profiler’s agreement increased from 71.3% (κ = 0.63) to 73.9% (κ = 0.67) after manual review, demonstrating that current automatic staging of these devices is still not as accurate as human expert analysis23. Several disorders can impact sleep structure, possibly affecting the performance of automatic staging, yet most devices have only been validated against PSG in healthy populations. Evidence in clinical populations is limited (Table 2). Accuracy can also be affected by inter-user variabilities, such as age and sleep hygiene and structure118, as well as intra-user variability and first-night bias. For example, sleep spindles, autonomic activation, and N3 stage have shown the least between-night variability and strongest stability in users, while sleep time duration, REM stage, and sleep efficiency show the lowest stability, suggesting that two-night studies may be necessary for accurate profiling of these metrics23.

Improving automatic scoring is crucial for establishing the clinical validity of these devices. However, this task is complicated by the significant variability in interscorer agreement. While the overall interrater reliability of manual PSG scoring indicates substantial agreement (κ = 0.76), the agreement for specific sleep stages varies considerably: fair for N1 (κ = 0.24), moderate for N2 and N3 (κ = 0.57 for both), substantial for REM (κ = 0.69), and substantial for Wake (κ = 0.70)5. This variability complicates the validation of automatic scoring systems against PSG standards. Furthermore, this subjectivity inherent in manual scoring can be transferred to trained models when they rely on single-scorer annotations4,117. Interscorer agreeability has also been shown to be lower for scoring the data from EEG-based wearable devices, e.g., κ = 0. 66 for a wearable device vs. κ = 0. 76 for PSG in one study32 and κ = 0.94 vs. κ = 0.97 in another21. Ensuring the accuracy and validity of these devices requires the development of evaluation frameworks, collaboration between stakeholders, and further research to improve device performance across various populations.

Regulatory issues

Challenges related to regulatory issues for EEG-based wearable sleep-tracking devices are multifaceted, requiring a delicate balance between ensuring quality and safety and fostering innovation. Most wearable devices are classified as lifestyle and fitness products and are often not subject to the same level of regulatory scrutiny as medical devices. The absence of clear regulatory oversight policies governing these devices can lead to the emergence of products with unknown safety and accuracy, posing risks to consumers and undermining trust in wearable health technologies.

Integration into clinical practice requires devices to be regulated, providing credibility and reliability for medical professionals and patients. However, current regulatory pathways can create market barriers, particularly for small companies and start-ups. In the European Union (EU), manufacturers must comply with the Medical Device Regulation (MDR) 2017/745 put in place in 2021, leading to additional requirements for software products, including wearables119. However, with no centralized regulatory body, the process is complicated, and time-to-certification can take 13–18 months120. In the United States (US), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates medical devices. Its 510(k) process allows for an accelerated clearance, allowing wearable devices to be marketed upon demonstrating substantial equivalence to an existing medical device121,122,123. Furthermore, with the increasing use of artificial intelligence (AI), new regulatory frameworks are being developed, such as the European Commission’s AI Act, which aims to harmonize rules for AI systems and promote development while addressing possible risks124,125,126. These regulations can be especially challenging for small- and medium-sized enterprises or academic researchers developing new devices, often hindering the availability of innovative devices for medical use. In navigating these multifaceted regulatory landscapes, the role of ethical design standards like IEEE Std 7000™-2021127 becomes crucial. This standard offers a methodology to integrate ethical considerations into system design, emphasizing communication with stakeholders and ensuring their ethical values are traceable throughout the design and implementation. By leveraging such ethical design, developers can navigate regulatory challenges more effectively, ensuring the alignment of their products with ethical considerations and contributing to the attainment of regulatory approvals. To support innovation, efforts have been made to accelerate the development and adoption of new devices, such as the FDA’s real-world evidence program in the United States128 and the DiGA Fast-Track in Germany129.

Data privacy and security

EEG-based wearable sleep-tracking devices pose distinct data security risks, as brain wave data can reveal various personal details such as potential predispositions to certain diseases or disorders, as well as age and sex assigned at birth130. Ensuring data privacy and security is crucial to protect users from potential abuses of their data. In the EU, the key framework for protecting personal data is the European General Data Protection Regulation ((EU) 2016/679, GDPR) which grants individuals the right to access, alter, or delete their personal data and restrict its processing131. The EU’s MDR also requires adherence to the GDPR. Additionally, the EU has introduced a Directive on Security of Network and Information Systems to harmonize cybersecurity regulations132. In the US, data privacy regulations are less strict compared to the EU. Nonetheless, specific rules apply to healthcare data, particularly the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). HIPAA establishes relatively broad permissions for the use of protected health information, often making individual consent unnecessary, and devices not intended for use within the healthcare context of HIPAA-covered entities are not subject to these regulations133.

To mitigate data privacy and security risks linked to wearable devices, strategies such as using advanced cybersecurity tools like blockchain, developing transparent data user agreements, updating outdated regulations, and raising individual awareness of security risks could be employed. Furthermore, following standards like IEEE Std 7000™-2021127 reinforce ethical considerations and values in system design, enhancing the overall trust of these devices. Implementing robust data privacy and security measures will foster users and healthcare professionals’ trust, facilitating the integration of these devices into clinical practice.

Availability

One of the main challenges with integrating EEG-based wearable devices into clinical practice is addressing availability concerns and ensuring equal access to these technologies. Users with higher digital literacy and socioeconomic resources are more likely to benefit from wearable devices, which in turn can exacerbate disparities in healthcare access. Public health policies and reimbursement strategies should be designed to promote equal access to these devices and cover the costs associated with wearable data reviews and prescribing. This would encourage healthcare providers to adopt wearables in clinical practice.

In the US, the Center for Medicare134 and Medicaid Services has established new reimbursement codes for remote patient monitoring. In Germany, a fast-track process for low-risk medical devices, including wearables, was introduced in the Digital Health Care Act. These digital health applications, referred to as DiGA, are intended for direct patient use and can be prescribed by physicians or psychotherapists in primary care settings129.

Behavioral change in clinicians

Maintaining behavioral change in clinicians is crucial for the successful integration of EEG-based wearable devices in clinical practice. Clinicians are often hesitant to adopt new technologies for various reasons, such as unfamiliarity, concerns about data privacy, and compatibility with existing clinical systems. Addressing these concerns requires a comprehensive approach that focuses on easing the transition for clinicians. First, seamless interoperability between wearables and existing hospital systems must be ensured without compromising patient privacy or data accessibility. Second, a strong body of clinical evidence demonstrating the benefits and safety of wearable EEG-based devices is needed to increase patient and clinician trust. Finally, comprehensive training and ongoing support must be provided for clinicians, incorporating structured learning modules about wearables and their clinical applications.

Usability

Usability remains a significant challenge for wearable EEG-based devices, particularly in terms of comfort and impact on perceived sleep quality. A study by Mikkelsen et al. (2019)37 that utilized in-ear EEG devices revealed that 85% of participants rated their sleep quality as bad or bearable on the first night, and 75% of participants reported the comfort of the earplugs as bad or bearable on the first night. Only 10% of participants indicated that the earplugs did not negatively impact their sleep at all during the first night of recording18. To ensure wider uptake and consistent usage of these devices, it is vital to address issues related to user experience. Manufacturers should prioritize improving designs by, for example, making them lighter, incorporating soft, breathable textiles in headbands, and utilizing ergonomic designs that better conform to users’ head and ear shapes. Additionally, ensuring that devices are easy to apply correctly, as well as offering clear instructions and support, can further enhance the user experience. By focusing on improving usability, manufacturers can make wearable EEG-based devices more appealing to users, ultimately leading to better patient adherence and more high-quality data collection.

Subjectivity

Subjective sleep assessments are essential for a comprehensive understanding of sleep health, especially in at-home monitoring. These assessments provide insights into perceived sleep quality, complementing objective measures from wearable devices. Common methods include sleep diaries, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)135, and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)136. For example, a study comparing single-channel EEG, actigraphy, and sleep diaries in older adults found that while total sleep time agreement was high, it decreased in participants with mild impairment and Alzheimer’s, showing that sleep diaries capture different sleep aspects. Integrating subjective assessments with wearable EEG data can provide a more comprehensive view of sleep health, identifying issues that objective measures alone may miss55. Including these assessments in studies and at-home monitoring enhances sleep health understanding and helps tailor interventions. More studies should combine both methods to better capture different aspects of sleep.

Clinical practice

As sleep monitoring devices gain traction, healthcare professionals and policymakers face numerous challenges when integrating these technologies into clinical practice.

There are various types of wearables and nearable devices available for sleep monitoring, each offering different advantages and levels of accuracy. Wearable nasal flow devices have proven to be particularly useful for diagnosing disordered breathing-related sleep disorders like OSA, offering diagnostic accuracy comparable to PSG with less invasiveness137,138,139,140. Nearable devices, such as an audio-based system has achieved 87.00% agreement with PSG in sleep stage classification141, and a contactless breathing monitor has shown high sensitivity for deep and REM sleep (75.00% and 74.80%, respectively), but lower sensitivities for light sleep and wake (59.90% and 57.10%, respectively), outperforming some wrist-worn devices142. Wrist and finger-based wearables, including devices like Fitbit, Apple Watch, Garmin, Polar, Oura Ring, WHOOP, and Somfit, are popular for home-based sleep monitoring due to their non-invasiveness. These devices are effective in detecting sleep versus wake states but struggle with specific sleep stage detection (κ = 0.20–0.65)143,144,145,146.

Overall, EEG-based wearables provide superior accuracy compared to wrist-based devices, which, while offering greater user-friendliness and cost-effectiveness, have lower accuracy in clinical populations. For example, EEG headbands have shown higher accuracy compared to actigraphy for sleep quality parameters147, and the Zmachine has shown higher agreement with PSG compared to Fitbit in psychiatric patients148. Integrating EEG-based wearables into clinical practice is crucial for precise sleep monitoring, especially in clinical populations where accuracy is paramount. However, the choice of sleep monitoring technology should be tailored to the specific needs of the patient. For instance, patients with suspected sleep-related breathing disorders may benefit more from nasal wearables, while wrist-based wearables might be more suitable for healthy populations requiring long-term monitoring due to their comfort and ease of use.

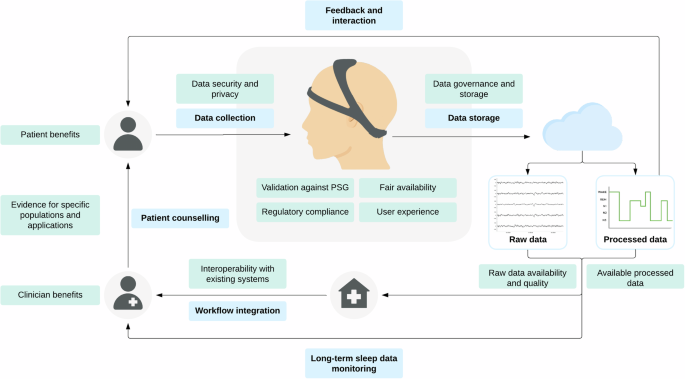

To assist clinicians in evaluating and incorporating wearable sleep-tracking devices into their daily practice, we present a comprehensive list of topics to consider (Table 4). This list covers devices’ available data, validation against PSG, regulatory status, evidence for specific clinical populations and applications, and fair availability. It also addresses the potential benefits for patients and clinicians, such as cost-effectiveness, and the challenges of workflow integration, including electronic health record integration, staff training, billing, and data review. Finally, the list highlights the crucial aspects of data rights, governance, storage, and privacy. By carefully considering these factors, clinicians can potentially adopt wearable sleep monitoring devices effectively, paving the way for a new era of connected remote patient care in sleep monitoring. To further illustrate the proposed integration process, Fig. 1 outlines the steps for integrating EEG-based wearable devices into clinical practice, from data collection to clinician review and patient counseling, highlighting key considerations at each step.

This figure outlines the steps (blue) of data collection from users via wearable devices, followed by data storage and data processing to yield both raw and processed data. Processed data is supplied back to the user for feedback and interaction, while both raw and procsessed data are provided to the clinician for review, enabling long-term sleep data monitoring. The clinician then utilizes this data for patient counseling. The figure emphasizes key considerations (green) at each step, such as the validation results and user experience of the device, data privacy, data availability and quality, interoperability with existing systems, integration into the clinicians’ workflow, and benefits for clinicians and patients. PSG: polysomnography.

EEG-based wearable sleep monitoring devices hold great potential for transforming the field of sleep medicine by offering a more accessible, cost-effective, and patient-centric approach to sleep assessment. This paper has delved into the current state and applications of these devices, exploring their role in understanding sleep in various clinical populations, the effect of interventions on sleep patterns, and daily aspects of sleep. For instance, these devices have provided insights into sleep alterations in patients with NDDs and the effects of lifestyle factors such as diet and stress on sleep patterns, and vice versa.

However, the integration of these technologies into clinical practice presents several challenges, such as validation against PSG, regulatory compliance, data privacy and security, and patient and clinician benefits, which must be addressed. This paper has provided a comprehensive list of factors to consider to effectively adopt wearable sleep monitoring devices in clinical settings. Clinicians should carefully evaluate the available data, validation results, regulatory status, evidence for specific clinical populations and applications, and fair availability. The potential benefits and challenges for both patients and clinicians should be weighed, including the improvement of clinical workflows, cost-effectiveness, remote patient care, and the complexities of integrating these devices into existing systems. Moreover, addressing the critical aspects of data rights is crucial to maintain patient and clinician trust.

As we look toward the future, the continued exploration of wearable sleep monitoring devices in specific clinical populations and applications will be crucial. Future research should focus on furthering the devices’ validation and establishing best practice guidelines for their use, ultimately aiming to seamlessly integrate them into clinical practice. Sleep monitoring devices may pave the way for a new era of connected remote patient care in sleep monitoring, enabling personalized and effective sleep disorder management. However, this requires a collaborative effort between researchers, healthcare professionals, device manufacturers, and policymakers to ensure that these technologies are responsibly and ethically integrated into the clinical landscape.

Responses