Effect of Baduanjin exercise on health and functional status in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a community-based, cluster-randomized controlled trial

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a common, preventable, and treatable disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms, partially reversible airflow limitation, impaired quality of life, and increased mortality1. Approximately 300 million people worldwide have COPD, which is a leading cause of mortality and morbidity2. By 2030, COPD is estimated to become the third leading cause of death and the fifth largest economic burden in the world3. The incidence of COPD is estimated to continue increasing over the next 40 years. By 2060, more than 5.4 million people may die of COPD and related diseases annually4. There are 99.9 million COPD patients in China, according to the latest report5. In 2017, COPD mortality was 68 per 100,000 persons and was the fourth major cause of disability-adjusted life years in China6. Therefore, COPD is a major disease burden both in China and worldwide.

Chronic and progressive dyspnoea, cough, and sputum production are the most common symptoms of patients with COPD. Combined with irreversible airflow obstruction, these symptoms can result in a gradual decline in lung function and a reduction in patients’ exercise capacity and quality of life7. Moreover, patients with frequent exacerbations experience a more rapid decline in physical activity8,9. In addition, respiratory muscle damage is common in COPD patients and leads to impaired muscle function, reduced exercise capability, and decreased activity10,11; therefore, individuals with COPD are less active than those without COPD12. Physical inactivity leads to higher rates of mortality and poorer quality of life in patients with COPD13,14. To improve patients’ quality of life and reduce mortality, exercise training should be recommended and offered to all COPD patients with reduced physical capacity or physical activity levels15. Exercise training can help relieve dyspnoea and fatigue and improve lung function, physical and mental states, exercise tolerance, and quality of life in patients with COPD independent of age, sex, level of dyspnoea, or disease severity11,16,17. Therefore, exercise training is considered a key component of pulmonary rehabilitation programs18. The type of training most suitable for COPD patients depends on their physiological requirements and individual demands.

Baduanjin exercise (BE) is a mild- to moderate-intensity aerobic exercise. BE routines are slow-paced and simple to learn and involve endurance training, flexibility training, mild exercise, and respiratory regulation. BE does not require any apparatus and can be performed anywhere. Therefore, BE is appropriate for individuals with low exercise tolerance and activity limitations19,20. BE training has been widely used for patients with COPD and has been demonstrated to be effective21,22. However, many BE studies have been performed in relatively small samples, have been conducted in outpatient or ward settings in general hospitals and/or feature BE training provided primarily by hospital healthcare professionals19,20,21,22 rather than by general practitioners in community settings via face-to-face exercise training. General practitioners are also known as village doctors in rural China. Village doctors (formerly known as “barefoot doctors”) act as community health workers and serve on the front line of primary healthcare in rural China23,24. Since the 1960s, the role of a village doctor has been to provide public health services and basic primary healthcare23. Owing to the nature of their work, village doctors must complete various levels of medical training organized by local health authorities every year. Their duties now also include follow-up management of patients with chronic diseases24. Village doctors are usually the first people to identify health problems and thus play an important role in managing the problems of patients with COPD. Research on village doctor care has shown that village doctors can effectively manage patients with diabetes and hypertension25,26,27.

The aim of the present study was to investigate whether village doctors in China can lead BE training and whether BE training can improve the health status of patients with COPD (compared with a control) over a six-month period.

Patients and methods

Study design

Three groups of patients with COPD participated in this community-based cluster-randomized controlled trial, which was conducted from May 2020 to October 2020 in Xuzhou City, Jiangsu Province, Eastern China. This region contains six rural districts with 2040 village clinics and an agricultural population of seven million. Approximately 169,000 individuals with COPD were registered in all the village clinics (an average of 83 patients per village clinic). To facilitate the intervention, we defined the study sample as patients in the village clinics rather than individual patients with COPD. In the first stage, one township was selected from each rural region. In the second stage, three village clinics were selected from each township using a random sequence based on the number of registered patients with COPD. In the final stage, patients registered for COPD management at these clinics were included in this study. A total of 472 participants were enrolled and randomly allocated to a control group or one of the intervention groups. The participants in the control group received usual care. The participants in the intervention groups received usual care plus BE or conventional pulmonary rehabilitation (CPR). As the study was conducted during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, all the study procedures complied with COVID-19 prevention and control measures (i.e., wearing masks, maintaining an interpersonal distance of more than one metre, and leaving one vacant seat between every two people). The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for cluster trial guidelines were followed28.

Participants

Patients were included if they had been diagnosed with COPD and were registered for COPD management, met the 2017 Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines2, volunteered to participate in the study, and signed an informed consent form. The other inclusion criteria were age 40 to 75 years; COPD grade II or III (grade II: 50%≤forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) < 80% of the predicted value; grade III: 30% ≤ FEV1 < 50% of the predicted value); stable phase of COPD; no respiratory infections or acute exacerbations of COPD during the last four weeks; no engagement in BE or similar Qigong exercises or daily aerobic exercises during the last six months; and the ability to communicate well. The exclusion criteria were the presence of diabetes mellitus, active tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, lung cancer, congestive heart failure, unstable angina pectoris, or myocardial infarction within 12 months before enrolment; epilepsy within 12 months before enrolment or epileptic seizures; chronic liver and kidney disease; glaucoma; limited physical activity or other reasons why participants could not perform BE training; participation in any other clinical studies in the last six months; and bipolar depression or other serious psychological disorders. The endpoints were the final follow-up scores for each participant. Participants were considered lost to follow-up if they lost contact, declined to communicate, or could not complete the visit owing to the aggravation of the disease.

Intervention protocol

Control group

The control group received usual care, which included encouragement to quit smoking, vaccination, oxygen therapy, suggestions for rehabilitation training, and standardized medication prescribed by general practitioners based on the patient’s individual needs. Every two months, the caregivers were asked to ascertain each patient’s health status via telephone or face-to-face interviews, record the patient’s health status, and report this information to our research group. Participants who had experienced deteriorating health received medication or were referred to a respiratory specialist according to the GOLD guidelines. The content and frequency of the usual care services were irregular.

CPR group

Training of rural doctors

A total of 12 village doctors from six village clinics, six general practitioners (nurses) from community health service centres, and three members of our team participated in 2-day CPR skills training. The training content was formulated according to previous studies and included upper limb exercise training, breathing exercises (pursed-lip breathing, deep and slow abdominal respiration, and diaphragmatic respiratory rehabilitation training), endurance training (e.g., walking, chest expansion exercise, handy-bike exercise, static cycling, treadmill, and circuit training), resistance training (dumbbell lifting, squat up training), cough and expectoration training, and structured health education sessions, which included health self-management, psychological intervention, nutritional support, and smoking cessation support29,30.

CPR implementation

The CPR group received the usual care plus CPR. There were three CPR groups per village, with ~10 participants in each group. Each group engaged in exercise twice weekly under the guidance of the village doctors. Each exercise session lasted 60 min and included warm-up (~5 min), breathing exercises (~10 min), endurance training (20–30 min), resistance training (20–30 min) and cool-down (~5 min). In the first month, the sessions were supervised by physiotherapists and respiratory specialists with attending or above technical roles (some physiotherapists were hired by our study group) and members of our research team. In the second month, the sessions were supervised by our research team. From the third to sixth months, the sessions were supervised by a general practitioner from the community health service centers. All exercises were performed step by step in an orderly manner. Any participants who experienced discomfort were advised to stop exercising immediately. The participant education sessions were conducted twice per week by members of our research team; each session lasted for 60 min.

BE group

Training of rural doctors

A total of 15 medical personnel (12 village doctors from village clinics and 3 members of our research team) received 2 days of BE training from professional trainers (each with a training certificate from the General Administration of Sport of China) from the Xuzhou Qigong Association. The Baduanjin steps are as follows: 1. Pressing the Heavens with Two Hands, 2. Drawing the Bow and Letting the Arrow Fly, 3. Separating Heaven and Earth, 4. Wise Owl Gazes Backwards, 5. Punching with Angry Gaze, 6. Bouncing on the Toes, 7. Big Bear Turns from Side to Side, and 8. Touching Toes then Bending Backwards. On the first day, the medical personnel received 8 h of training (4 h in the morning and 4 h in the afternoon). On the second day, they attended group practice from 8 am to 12 pm and from 2 pm to 3:50 pm, supervised by the professional trainers. From 4 pm to 6 pm, the personnel were divided into five groups for examination.

BE implementation

In addition to usual care, participants in the BE groups received BE training. During the first 2 weeks, the training was led by a village doctor, guided by professional trainers, and supervised by our research team. After the first two weeks, the training was led by a village doctor for two weeks and supervised by our research team members. The participants practised at home from the second to the sixth month. The participants were required to practice for at least 5 days a week, twice a day, for 30 min per session. The participants reported their exercise status to the village doctors via text messages or WeChat before 6:30 pm every day. At 7 pm each evening, the village doctors commented on the participants’ daily activities. The doctors asked participants who had not engaged in exercise that day about their reasons for not practising and reminded them to participate in the exercise the following day.

Termination and withdrawal criteria

All the participants were informed that they had the right to withdraw from the trial at any time. The reasons for withdrawal were recorded by the village doctors. The criteria for withdrawal were (1) the occurrence of exercise-related adverse events or inability to tolerate the exercise; (2) other serious acute diseases that required treatment; (3) <80% compliance with the required participation time; (4) joining other nonpharmacological interventions or pulmonary rehabilitation programs; and (5) inability to cooperate in completing all sessions, management and evaluation.

Outcomes

Primary outcome: The primary outcome was the change in health status, as measured by the COPD Assessment Test (CAT)13 score, and dyspnoea from baseline to the end of the follow-up period, which was collected on paper forms. The CAT scores included responses on eight items, each scored from 0 to 5. The total possible score was 0–40, with a higher score indicating a poorer health status. The Cronbach’s alpha of the Chinese version of the CAT was 0.80531. Dyspnoea was assessed with the modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea scale32. The total possible score range is 0–4, with a higher score indicating more severe dyspnoea. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the mMRC scale was 0.74433.

The secondary outcomes were changes in body endurance, psychological status (depression and anxiety), and dyspnoea; these data were also collected with paper forms. Body endurance was measured with the six-minute walking distance (6MWD) performance, which was carried out according to American Thoracic Society guidelines34. Depression and anxiety were screened and measured via the Chinese version of the 14-item Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). This scale comprises seven items related to anxiety (HADS-A) and seven related to depression (HADS-D). The total possible score range is 0 to 21, with subscale scores ≥8 indicating possible anxiety or depression35. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the HADS and its two subscales were 0.89, 0.76, and 0.83, respectively36.

Other demographic variables

The general characteristics of the patients were collected via a self-designed questionnaire and included age, sex, years of education, smoking status, alcohol consumption, disease course, and regularly used medications. The height and weight of the patients were measured, and the body mass index was calculated. Individuals who smoked ≥one cigarette per day for > three months were classified as smokers, and individuals who consumed ≥30 g of alcohol per week for ≥one year were classified as drinkers. Any medications prescribed for COPD in the previous year and used continuously (no interruption of use for ≥two consecutive days) were classified as regular medications.

Sample size

The primary outcome was scores on the CAT13 at baseline and six months. On the basis of a previous report37, we assumed that (μ1 − μ2) = 3 would indicate a meaningful difference in CAT scores between the BE and control groups following the intervention. Using a two-level cluster random design, a total of 2N patients were selected and randomly assigned to the intervention or control group. The probability of Type I error was 0.05, and the test power was 0.8. A total of 20 participants were included from each village clinic. The allowable error was 0.25 times the standard deviation, and the intragroup correlation coefficient ρ was estimated to be 0.05, according to the following formula: n = 2(Z1-α/2 + Z1-β)2σ2[1 + (n − 1)ρ]/(µ1 − µ0)2. We estimated that each group needed at least 122 participants from six village clinics. Because the rate of stable COPD patients is 85%38, 144 patients were needed per group; therefore, 24 managed COPD patients were needed per clinic. Assuming a rate of loss to follow-up/ineligibility of 15%, we estimated that at least 27 patients would be needed from each clinic. A total of 18 village clinics were selected, and all COPD patients were assessed for health status, psychological factors, and disease severity.

Randomization

Signed informed consent was obtained from each participant. An independent investigator who had no contact with the village clinics or participants randomly divided the 18 village clinics into the BE group, CPR group, or control group at a 1:1 ratio based on a random number table.

Allocation concealment

Another independent investigator selected the village clinics. The generated random allocation sequence was placed in sequentially encoded, sealed, opaque envelopes and locked in the investigator’s office, which was used to ensure concealment until clinical identification. Village clinics were automatically included in the study when the numbered envelopes were opened, and the numbers on each envelope ensured that all clinics were enrolled after being randomly assigned.

Masking

A single-blind method was used in this trial. The investigators and statisticians were blinded to the grouping. To minimize bias, all outcome evaluators were blinded to the participant grouping and research objectives. Unblinding was performed at the end of the statistical analysis.

Adverse event reporting and safety assessments

Adverse events that were directly attributable to the study interventions, as well as those not attributable to the study interventions, were monitored during the intervention period. Any participants who experienced dyspnoea, dizziness, falls, muscle strain, or COPD exacerbation during exercise were advised to immediately stop training and see a doctor. Detailed records of any adverse events were kept and reported to our ethics committee within 12 h.

Statistical analysis

All data analysis was conducted according to the principle of intended processing. Missing values were replaced via the last observation carried forwards method. To ensure accuracy, we carefully checked the data before analysis, especially if two complete datasets appeared to be very similar. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 17.0 software (SPSS 17.0, Chicago, IL, USA) was used to analyse the data. The quantitative data are expressed as the means ± standard deviations and were tested via group t tests or nonparametric tests. The number and percentage of cases were tested via the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact probability method, and score data were tested via nonparametric tests. One-way analysis of variance was conducted to detect differences among the three groups. For significant differences (two-sided P value < 0.05), we used the post hoc Bonferroni correction to examine differences between each pair of group means. To preserve the original randomization, an intention-to-treat analysis was used.

Results

Setting

Group characteristics

There were no group differences in the number of participants at baseline or six-months or in the number of medical personnel in each community (Table 1).

General characteristics of the study population

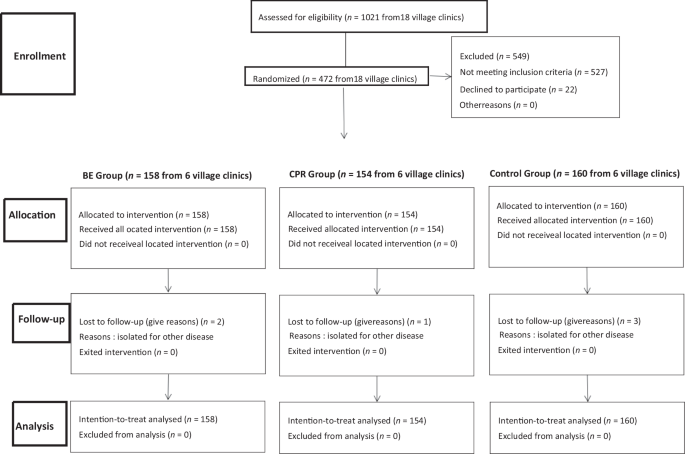

Participants were recruited from January 2020 to March 2020. Baseline data were collected from participants from April 1 to 30, 2020. The trial was conducted from May 2020 to October 2020 in Xuzhou City. The final survey was completed from November 1 to 14, 2020. In this study, 1021 patients registered in 18 village clinics met the 2017 GOLD criteria. A total of 22 patients declined to participate, and 527 patients did not meet the inclusion criteria. Figure 1 shows the CONSORT diagram for cluster trials: 158 participants from six clinics were randomly allocated to receive BE plus usual care, 154 participants from six clinics were randomly allocated to receive CPR plus usual care, and 160 participants from six clinics were randomly allocated to receive usual care. There were no significant differences in general characteristics among the three groups at baseline (Table 2). At the end of the study, there were 466 completers and six non-completers (two in the BE group, one in the CPR group, and three in the control group). No participants received other non-pharmacological treatments during the six-month follow-up.

Flowchart of participant screening, randomization, and follow-up. A total of 1021 participants were assessed, 472 were randomized into BE (n = 158), CPR (n = 154), and UC (n = 160) groups. The diagram details allocation, follow-up, and reasons for attrition.

Participant attendance at exercise practices

A total of 97.5% of the participants fully participated in all the BE practices. The participation rate for the CPR group was 90.38%. Non-participation in the BE group was due to the occurrence of acute exacerbation; in the CPR group, participants showed a lack of persistence in the endurance exercise, especially during the early intervention period.

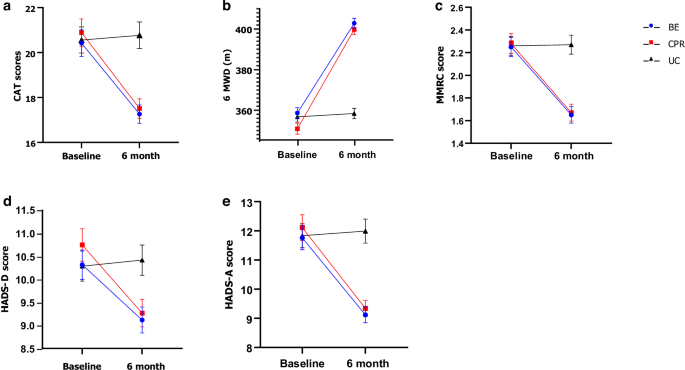

Changes in health status

An examination of the trends in health status changes over the six-month period revealed that all individuals from the BE and CPR groups demonstrated a stable improvement trend; there were no variations in the control group. The CAT scores in the BE groups were significantly lower than those in the control group (P < 0.05) but not significantly different from those in the CPR group (P > 0.05) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Changes in clinical outcomes from baseline to 6 months across BE, CPR, and UC groups. a CAT scores, b 6MWD, c MMRC scores, and d, e HADS-D and HADS-A scores improved significantly. Data are shown as mean ± standard error, with groups represented by blue (BE), red (CPR), and black (UC).

Changes in body endurance

After six months, the 6MWD performance in the BE group was significantly longer than that in the control group (P < 0.05), but there was no significant difference between the BE and CPR groups (P > 0.05) (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Changes in HADS-D scores

The mean baseline HADS-D scores of participants with symptoms of depression in the BE, CPR, and control groups were 10.32 ± 4.01, 10.75 ± 4.31, and 10.29 ± 4.12, respectively; the scores did not differ significantly among the three groups (F = 0.595, P = 0.552). The BE group had lower mean HADS-D scores after the six-month intervention (t = 2.945, P = 0.010) than the control group did. However, this improvement in the BE group was not statistically significant compared with the CPR group (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Changes in HADS-A scores

At baseline, the mean HADS-A scores were 11.76 ± 5.15, 12.11 ± 5.45, and 11.83 ± 5.19 for participants with anxiety in the BE, CPR, and control groups, respectively; the scores did not differ significantly among the three groups (F = 0.193, P = 0.825). After the six-month intervention, the mean HADS-A scores of the BE group were lower than those of the control group (t = 6.210, P < 0.001). However, this improvement in the BE group was not statistically significant compared with the CPR group (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Changes in dyspnoea symptoms

There was no statistically significant difference in the mean mMRC scale scores among the BE, CPR, and control groups at baseline (F = 0.032, P = 0.969) (Table 1). The mean mMRC scale scores of the BE group were lower than those of the control group after the six-month follow-up (t = 5.719, P < 0.001). The mMRC scale scores in the BE group were not significantly different from those in the CPR group (P > 0.05). The mMRC scale scores of the control group did not change throughout the study period (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Adverse events

Throughout the study, 8 participants in the BE group, 10 participants in the CPR group, and 15 participants in the control group experienced at least one serious adverse event (χ2 = 2.360, P = 0.307), including hospitalization for physical illness. However, none of these events were judged to be related to the training procedures or intervention.

Discussion

The main purpose of the current study was to test the effect of a village doctor-led BE intervention to manage patients with COPD. The results showed that village doctors can learn to administer BE interventions to patients with COPD. This community-based cluster randomized controlled trial in rural China revealed improvements in the health status, body endurance, and psychological status of patients with COPD with BE training. To our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate that a village doctor can lead BE interventions to manage patients with COPD.

The observed completion rate (98.7%) differed from that reported in previous studies of BE programs; one study reported a completion rate of 89.5%39, and another reported a completion rate of 67.8%40. These differences may be related to the timing and location of the exercise, whether the exercise was supervised, and the level of supervision. The high completion rate in the present study indicates that BE is simple and easy to learn. Similar to previous studies39, patients with COPD in this study exhibited high compliance and did not experience adverse events associated with the intervention, confirming the feasibility and safety of this program.

The CAT scale, which is based on St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire, is used to evaluate the health status of COPD patients and has demonstrated reliability and validity13. The CAT has not only been shown to be useful in measuring pulmonary rehabilitation41 but has also been used to measure the effect of exercise on patients with COPD42. High CAT scores indicate that patient quality of life is substantially reduced; CAT scores were improved after patients performed BE or CPR and exceeded the minimum clinically important difference of 3 points. The present results were consistent with the findings of two recent systematic reviews and meta-analyses, which confirmed that BE can improve the health status of patients with COPD, as shown by a reduction in CAT scores21,43. This result may be explained by the fact that BE not only includes respiratory exercise but also involves upper and lower limb exercises to further strengthen the role of the auxiliary respiratory muscles. BE also promotes the smooth flow of Qi and blood and regulates the yin–yang balance44. The lung function of patients with COPD correlates with CAT scores45. BE may enhance cardiopulmonary function46, which may provide another explanation for why BE reduces CAT scores. In the present study, the effect of BE was similar to that of CPR, which indicates that BE could be used as rehabilitation training for patients with COPD.

A reduction in endurance capacity is one of the main characteristics of COPD47. The 6MWD test is used to evaluate the endurance capacity of patients with COPD48,49. After six months of exercise intervention, the 6MWD performance of the participants in the BE group was significantly better than that of the participants in the control group. These findings indicate that BE can improve physical activity levels and cardiopulmonary endurance. These results are consistent with those of previous studies21,43, indicating that BE can improve the cardiorespiratory function of patients with COPD46,50 and can substantially improve lower extremity strength48. The mean 6MWD increase in our study was 48.21 m, which exceeds the minimum clinically important difference of 30 m51. However, this finding differs from the results of another study that reported that BE training only slightly improved 6MWD performance in patients with COPD40. In that study, the baseline 6MWD performance was 310.78 ± 13.03 m for COPD patients aged ~70 years. After a BE intervention, patients showed an increase in walking distance of 27.25 m (338.53 ± 13.42 m, P = 0.26)40. However, in the present study, a baseline 6MWD of 358.75 ± 32.80 m was observed in the BE group for patients aged ~61 years. The BE group showed a significant improvement in walking capacity (402.85 ± 30.43 m, P = 0.001) postintervention. This difference may be because the attrition rate was high (30%) in this study52. Previous research has reported a low adherence rate for individuals with a lower exercise capacity52. Another reason for the discrepancy may be differences in exercise intensity: our participants were asked to practice at least five days a week, twice a day, for 30 min each time. The previous study required participants to practice at least four times a week and at least once per day. This finding suggests that BE cannot improve participants’ endurance if the frequency and intensity of exercise are insufficient. A previous study showed that BE training for more than six months with an optimal training intensity may be more useful for COPD patients21. Another possible reason for the difference in findings across studies is age differences; our participants were 10 years younger than participants in previous studies. Participant age and baseline conditions affect the level of improvement in walking capacity in COPD patients; that is, patients over 65 years of age who have 6MWD baseline values above 350 m have less potential to increase their performance53. The present results suggest that the walking capacity of COPD patients may be affected not only by age and baseline values but also by pulmonary function, aerobic capacity, and other factors. The improvement in the endurance capacity of patients with COPD after BE may be because the various movements of BE involve different parts of the body, such as the waist, abdomen, back, legs, and arms. Through practice, the strength and flexibility of these parts can be enhanced. Long-term practice can increase the body’s flexibility and suppleness, improving muscle endurance and strength. These aspects of BE movements may be the keys to strengthening the lung capacity and diaphragm of COPD patients. Additionally, BE trains the respiratory muscles and improves the force of muscle contraction to stretch the patient’s trunk and limbs, providing the opportunity to strengthen the muscles and improve limb coordination and exercise performance21. In the present study, the 6MWD performance of the BE and CPR groups increased, but there was no difference between the groups, which indicates that the effect of BE was similar to that of CPR.

Since COPD is associated with a long disease course, a high likelihood of recurrence, a gradual decline in lung function, and difficulty breathing, patients (especially those with moderate or severe COPD) are prone to psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression54. Non-pharmacological interventions such as BE can reduce anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with COPD19,55. Participants in the BE group experienced greater alleviation of anxiety and depression symptoms than did those in the control group after six months of intervention. These findings indicate that BE can reduce anxiety and depression levels. The present results are consistent with those of previous studies reporting a therapeutic effect of BE for patients with depression and anxiety19,43,56,57. BE may reduce anxiety and depression levels because it emphasizes musculoskeletal relaxation, an empty state of mind, and breathing regulation. These BE elements play a very important role in reducing anxiety58,59. Studies have shown that slow and deep breathing patterns can correct the sympathovagal imbalance and produce a calming effect60,61. In adult animal models, rhythmic respiratory regulation has a calming effect on anxiety and panic states62. The results of this study showed that BE practice was significantly correlated with an improvement in depressive symptoms. This result may be explained by the fact that adiponectin levels are reduced in depressed patients, and BE interventions significantly increase plasma levels of adiponectin, which has antidepressant-like functions56. Some reports indicate that more frequent BE practice is associated with a greater reduction in depression19,56. When practising BE, attention is given to the integration of the body and mind. By relaxing the body and adjusting breathing, tension and anxiety can be alleviated, and emotions can be balanced. BE also helps individuals develop a sense of inner peace and concentration, which allows them to enter a meditative state and promotes spiritual growth and awakening. The HADS-A and HADS-D scores of the BE and CPR groups in the present study were not different after six months of intervention. These findings indicate that BE and CPR have similar effects, and both interventions can reduce anxiety and depression levels.

After six months of intervention, BE had a similar effect to that of CPR; participants in the two groups had greater reductions in mMRC scale scores than did participants in the control group. Our findings are similar to those of previous studies indicating that BE can alleviate dyspnoea in patients with COPD. BE is an aerobic exercise that improves respiration by increasing gaseous exchange, prolongs breathing and vital capacity63, and prevents COPD-related deterioration of lung function20. On the other hand, BE can also reduce the levels of IL-8 and C-reactive protein in the sputum, thereby alleviating the inflammatory response in patients with COPD64. Therefore, long-term BE training substantially improves patients’ respiratory muscle strength and endurance, thereby improving respiratory function and alleviating the symptoms of dyspnoea. After six months of intervention, the mMRC scale scores of the participants in the BE and CPR groups were greater than those of the participants in the control group, which indicated that BE had a similar effect to that of CPR.

Generally, improvements in exercise capacity, health status, and psychological disorders in COPD patients may be explained by the movement characteristics of the BE routine. First, BE includes endurance training, breathing muscle training, stretching training, and psychological adjustment, all of which are required for pulmonary rehabilitation. Second, muscle atrophy is very common in patients with COPD, and their lower limbs are weaker than those of healthy individuals; therefore, their physical capacity gradually decreases, and they may not be able to perform high-intensity exercise65. BE is a low-intensity aerobic exercise characterized by slow, coordinated postures that are suitable for COPD patients who have low exercise tolerance19,20,63. Furthermore, routine BE training involves coordinated musculoskeletal stretching and relaxation, diaphragmatic breathing (inhaling and exhaling through the nose), and mental concentration. Mental focus and relaxation are also integral parts of BE training. These factors may help COPD patients experience less fatigue during training and find training more pleasant, which may improve mental health and increase adherence to the exercise protocol. As exercise capability and lung function improve, COPD patients experience reduced psychological symptoms19,43,55,56,57 and improved dyspnea63,64, thus naturally experiencing a better quality of life20,21,22,39,40,43,46.

At present, the provision of CPR requires specialist services66. Pulmonary rehabilitation is a cornerstone of comprehensive management for patients with COPD. Pulmonary rehabilitation should form the basis of exercise training, the main objective of which is to increase the aerobic capacity of patients18. However, most patients with COPD do not adapt to high-intensity and sustained exercise training because of dyspnoea, fatigue, and older age67. In addition, high-intensity exercise may generate adverse effects, such as hypercapnia or lactic acidaemia68 and disturbed breathing patterns, which may further reduce exercise capability among patients with COPD69. Patients with COPD (particularly older and frailer adults) who experience positive effects from CPR tend not to maintain these effects six months after the completion of a rehabilitation program40. Like CPR, BE is a low-intensity aerobic exercise that can improve participants’ endurance. BE has several advantages. First, it is simple and easy to learn. Second, it does not require any apparatus, and its practice is not limited by time, location, or weather factors. Third, it is very safe and easy to maintain. Fourth, it includes both physical and mental exercise. Fifth, it is accessible to people of all ages and levels of physical strength and has few known side effects. Sixth, it has greater perceived therapeutic value in Eastern cultures40,43. Therefore, BE is less expensive and much more applicable than CPR.

The strengths of this study include the community-based, multicentre, two-level, randomized controlled design; the rigorous methodology; and the use of a sufficient sample size for the intention-to-treat analysis, which limits the risk of bias. The study was conducted in a primary care setting, and the results are applicable to COPD patients in the community.

This study had several limitations. First, the participants and village doctors could not be blinded; thus, the results may have been affected by subjective bias. Second, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, personnel movement and aggregation were restricted, and lung function (which is a major indicator of the patient’s disease state) was not directly assessed. Third, according to a previous study, the outcome of pulmonary rehabilitation exercise in patients with mild COPD may not be obvious, and patients with very severe COPD are susceptible to adverse events70. To ensure that reliable effects could be identified and to reduce adverse events, we did not include patients with stage I or stage IV COPD. However, a previous study showed that BE training offers better protection against acute exacerbation of COPD among GOLD stage I COPD patients and improves exercise capacity and quality of life among patients with advanced-stage COPD39. Therefore, future research should include real-world studies to ensure that patients with all stages of COPD are sampled. Fourth, as self-report questionnaires were used to assess anxiety and depression, health status, and dyspnoea, the possibility of response errors and bias cannot be ruled out. Finally, all participants were Chinese and were recruited from a single geographical area. Therefore, caution is needed before the results can be generalized to non-Chinese COPD patients and those living in other areas in China.

Conclusions

In conclusion, village doctors, who are often the first people to identify health problems, can learn and implement BE. BE could improve health status, increase 6MWD performance, reduce anxiety and depression symptoms, and relieve dyspnoea in COPD patients. BE had effects similar to those of CPR in improving subjective symptoms among COPD patients. Despite several study limitations, we believe that our results have important implications for public health. These findings suggest that BE is an effective pulmonary rehabilitation strategy for managing patients with COPD. There are currently 99.9 million patients with COPD in China5. Many have a poor understanding of COPD and quality of life, high rates of undertreated anxiety and depression, and very low rates of respiratory rehabilitation71,72. Additionally, rural doctors have very poor skills in managing patients with COPD73. BE is an inexpensive and practical method for improving the health status of COPD patients. Additionally, the simplicity and accessibility of BE for village doctors may increase their ability to manage patients and may increase patients’ compliance with management.

Responses