Effective climate action must address both social inequality and inequality aversion

Introduction

Why do some climate policies spark widespread public support while others ignite protests and backlash? Understanding the role of inequality aversion may hold the key.

Scholars have argued that social inequality threatens the goals of the Paris Agreement. Contributing to climate change mitigation is often individually costly, requiring additional expenditure on climate-friendly transport and food, adopting green technologies, and paying climate change taxes. Economic constraints can be a serious barrier for the less privileged, as climate action puts a greater strain on their budgets due to lower incomes and assets1,2,3.

The significance of another key factor related to inequality that can undermine support for climate policy and action is less well understood: inequality aversion (see Box 1 for a detailed explanation of this and other key concepts discussed in the following paragraphs). This refers to the disutility caused by differences between one’s own economic situation and that of others, which can dampen intrinsic motivation to support climate action. The Yellow Vest movement in France in 2018 illustrates this effect. The protests erupted in response to a carbon tax increase and were fueled by earlier tax cuts for affluent individuals, demonstrating the potential for public backlash against climate policies perceived as unfair4,5. Numerous other countries have experienced similar public backlash against climate policies6,7.

Addressing inequality aversion is critical to preventing backlash and fostering both support for climate policies and the adoption of costly individual climate actions (collectively referred to as climate cooperation). Previous research has highlighted that perceptions of disadvantage or injustice can undermine support for climate mitigation efforts8,9. However, the literature remains vague on the mechanisms linking objective inequality to intrinsic motivations and subsequent climate cooperation.

We develop a coherent theoretical framework based on the climate public goods game to show how the interplay of inequality and two forms of inequality aversion shape the level of climate cooperation within a population. These forms are, first, advantageous inequality aversion, the disutility of being better off than others, which encourages cooperation, and, second, disadvantageous inequality aversion, the disutility of being worse off than others, which discourages cooperation. We show that when inequality is absent or moderate, advantageous inequality aversion dominates and promotes climate cooperation. In contrast, pronounced inequality amplifies disadvantageous inequality aversion and undermines cooperation.

Our framework allows us to assess the impact of inequality and different climate policies on inequality aversion and subsequent climate cooperation. First, we show how inequality aversion promotes cooperation among homogeneous individuals. We then show how pronounced inequalities promote disadvantageous inequality aversion and undermine climate cooperation. Next, we highlight aspects of current mitigation strategies that overlook inequality aversion. Finally, we propose policy solutions that directly address inequality aversion to enhance climate cooperation and support the effective implementation of climate policies.

Advantageous inequality aversion fosters cooperation in homogeneous populations

We demonstrate the effects of inequality aversion using the climate public goods game, a standard tool for modeling contributions to climate change mitigation10,11. A stable climate is socially beneficial, but climate cooperation in the form of contributions to mitigation is individually costly. Thus, a self-interested individual has incentives to choose defection, like taking a cheap short-haul flight or voting against a carbon tax, over cooperation, like taking a more expensive, time-consuming train ride or voting in favor of a carbon tax. In the standard model, assuming self-interested preferences, defection yields higher benefits than cooperation, regardless of the level of climate cooperation in the population (Fig. 1a). This creates a social dilemma: if everyone follows their self-interest, the outcome is detrimental to all.

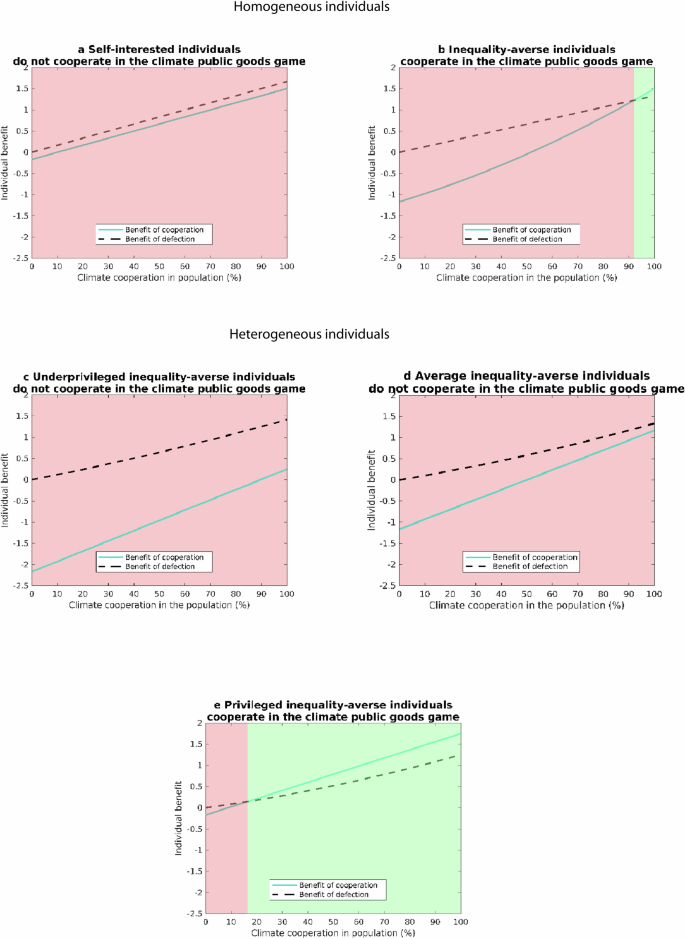

The solid green line represents an individual’s benefit from cooperation, and the dashed black line represents their benefit from defection, both depending on the expected level of climate cooperation in the population. a Homogeneous, self-interested individuals never cooperate in the climate public goods game, indicated by the red-shaded area. b Homogeneous, inequality-averse individuals cooperate when expected climate cooperation reaches a threshold of 92%, indicated by the green-shaded area. c Climate public goods game with inequality-averse heterogeneous individuals. Underprivileged individuals do not cooperate. d Average individuals do not cooperate. e Privileged individuals cooperate when climate cooperation reaches a threshold of 16%.

However, individuals often deviate from the standard model and behave differently. In experimental public goods games and analogous real-world settings, many individuals are willing to cooperate when they expect others to do the same—a behavior known as conditional cooperation12,13,14.

Conditional cooperation can be explained by inequality aversion15,16. Conditional cooperators experience discomfort when there is inequality in contributions. If they do not contribute while others do, they feel an intrinsic penalty for being better off than others, known as advantageous inequality aversion, which incentivizes them to cooperate. Conversely, if they contribute while others do not, they feel discomfort from being worse off than others, known as disadvantageous inequality aversion, which may incentivize them to defect15,17.

Therefore, if conditional cooperators expect the cooperation of a sufficient number of others, they will also cooperate to avoid “horizontal inequities”—inequities arising from different choices within equal groups18. Thus, if a sufficiently large number of others are willing to pay a premium to take the train on vacation instead of a cheap short-haul flight, they will do so too, to avoid advantageous inequality aversion. This is illustrated in Fig. 1b, which shows a climate public goods game with homogeneous inequality-averse individuals. The benefit of individual cooperation exceeds the benefit of defection when about 90% of the population cooperates for the climate. That is, if individuals trust that 90% of the population will contribute, the mitigation measures will be successfully implemented. The finding that social preferences can lead to universal cooperation has led scholars to advocate for promoting social norms of cooperation as an effective policy measure to address challenges arising from social dilemmas, such as contributions to climate mitigation19,20,21,22.

Disadvantageous inequality aversion undermines cooperation in heterogenous populations

While inequality aversion can promote cooperation in homogeneous populations, pronounced inequality greatly reduces this potential. This is because disadvantageous inequality aversion is typically a stronger motive than advantageous inequality aversion. People generally dislike being worse off relative to others more than they dislike being better off15,23. Consequently, when individuals perceive that their contributions to public goods exceed those of others, their incentives to defect increase.

Concerns about horizontal equity—such as choosing a more expensive train over a cheap short-haul flight to avoid feeling better off than others (addressing advantageous inequality aversion)—can be overridden by concerns about vertical equity18. Vertical equity pertains to fairness across different income levels; individuals with lower incomes may avoid paying a higher relative price for an expensive train ticket because it imposes a greater financial burden on them compared to wealthier individuals. This heightened financial strain exacerbates their disadvantageous inequality aversion, discouraging them from cooperating.

The presence of pronounced inequality strengthens the impact of disadvantageous inequality aversion relative to advantageous inequality aversion, leading to decreased cooperation. This pattern is illustrated in Fig. 1c–e. In this variant of the climate public goods game, the individuals involved pay the same average cost as before. However, while the average individual—the one paying the average cost—still pays the same, the financially underprivileged individual pays 50% more, and the financially privileged individual pays 50% less. This financial disparity, coupled with constant inequality aversion, leads the underprivileged individual to withhold their contribution to the climate public good (Fig. 1c–e). Both the increased financial costs and the increased psychological costs due to their underprivileged status contribute to this result. In contrast, the average individual still pays the same price as before. However, even they switch from cooperation to defection solely because of their lower status and associated disadvantageous inequality aversion.

Addressing disadvantageous inequality aversion promotes cooperation

What policies can address disadvantageous inequality aversion? Consider a policymaker with a fund to reduce the total cost of contributions by 50%. How should the available funds be distributed among three inequality-averse and heterogeneous individuals—one underprivileged, one average, and one privileged? Drawing on various distributive justice theories and current proposals to address the climate crisis24,25,26, the following discussion is based on a counterfactual analysis. In this scenario, financial costs are held constant at the average, but psychological or intrinsic costs differ: the underprivileged individual experiences costs fifty percent higher than the average, while the privileged individual faces costs half the average, as shown in Fig. 2a. This approach demonstrates the effect of an intervention on cooperation through inequality aversion alone, holding financial costs constant. A scenario that includes both financial and intrinsic costs is discussed in Supplementary Information Sections 1–3 and yields equivalent results.

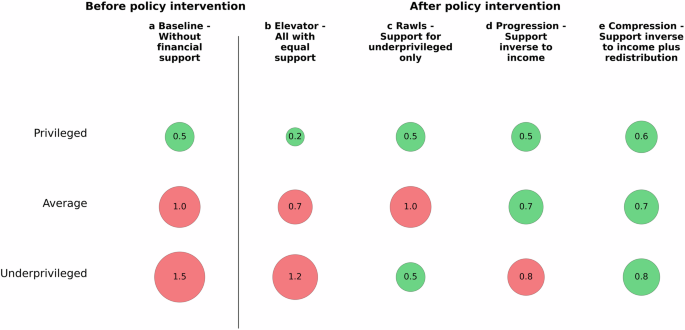

Numbers represent mitigation costs for the underprivileged (lower circle), average (middle circle), and privileged individuals (upper circle), with circle size proportional to individual contribution costs before the intervention (a) and after the intervention (b–e). Green indicates willingness for climate cooperation, while red indicates unwillingness.

Figure 2a shows the baseline scenario, before any intervention, in which only one of the three individuals cooperates (green circle) and two defect (red circles). The first intervention, Elevator, follows a Benthamite approach and divides the fund equally among the three individuals. As the elevator moves up one floor, status differences are preserved, producing the same outcome with only one cooperating individual (Fig. 2a).

Focusing on the least advantaged, Rawls transfers the entire fund to the underprivileged, making them open to cooperation. While two out of three individuals are now willing to cooperate, a Rawlsian approach has its limitations. By focusing only on the underprivileged, the intervention fails to motivate those in the middle of the distribution. Thus, at least when starting from a low level of cooperation, Rawls is not an ideal intervention strategy (Fig. 2c).

Progression supports the individuals in inverse proportion to their wealth. In our example, shown in Fig. 2d, the underprivileged receive 70% of the fund, and the average individual receives 30%. This strategy also results in two out of three individuals being willing to cooperate. Under the chosen parameters, the share given to the underprivileged is not sufficient to motivate them to cooperate. However, it is possible to motivate all individuals to cooperate by increasing the share allocated to the underprivileged. Progression, with its potential for further adjustment, is thus the most powerful strategy discussed so far.

Compression is even more powerful. It is based on the same logic as progression, except that it also redistributes wealth from the top. In the example shown in Fig. 2e, again 70% is transferred to the underprivileged and 30% to the average individual. In addition, the privileged individual’s cost is raised by 10%—a change that is sufficient to motivate the underprivileged individual to cooperate simply by reducing their inequality aversion, without transferring the money thus raised to them. The policymaker either gets their intervention at a discount or can use the money to further increase cooperation.

Discussion and conclusion

We have shown that social inequality not only limits climate cooperation among the less privileged due to economic constraints but also discourages it across broader society through disadvantageous inequality aversion. Consequently, policies should not focus solely on supporting the most disadvantaged while neglecting those at the center of the income distribution. Nor should policies aim to reduce costs equally for all, as this approach sustains inequality and the associated inequality aversion. Instead, policies need to reduce the disparities in the costs of climate action across broad segments of society. Rather than relying on highly regressive national carbon taxes, progressive systems should be implemented, with rebates inversely proportional to income. Our analysis also reinforces the case for a progressive global wealth tax to fund climate action25.

In our analysis, we have abstracted from the fact that the subjectively expected level of cooperation may not correspond with actual cooperation. People tend to robustly underestimate others’ willingness to cooperate in public goods scenarios, including climate action. As a result, defection may dominate not because individuals are genuinely unwilling to cooperate, but because of overly pessimistic expectations regarding the cooperativeness of others27,28. Therefore, providing transparent feedback about the actual willingness of others to support climate mitigation could positively impact cooperation, although recent research highlights the need to do so repeatedly and consistently29. Public awareness campaigns highlighting collective efforts and commitments, both domestically and internationally, can help correct misperceptions and foster climate cooperation.

Perceptions of inequality and disadvantage are also subject to cognitive biases30,31,32,33. People may have an overly pessimistic perception of disadvantage, due to the prevalent narrative of populist parties that the “ordinary people” are being taken advantage of by a “corrupt elite”6,33,34. A preference for populism is often associated with subjective disadvantage, and populist movements consistently oppose climate policy6,9,35,36,37,38. In light of this major contemporary issue, communicating accurate trends in inequality reduction or highlighting policies that effectively address inequality might be beneficial. Addressing these misperceptions through education and transparent communication can reduce undue pessimism and foster a greater willingness to cooperate.

So far, we have focused on the negative impact that disadvantageous inequality aversion exerts on climate cooperation. However, advantageous inequality aversion can also prompt reciprocal behavior. Building on this notion, policymakers should support citizens through robust welfare systems that reduce economic disparities and promote social inclusion. Linking such support to climate action initiatives can encourage citizens to reciprocate by engaging in climate-friendly behaviors. The Scandinavian welfare state model, which is associated with higher levels of social trust and lower levels of inequality, provides a pertinent example39,40. Trust, in turn, is a strong predictor of cooperation, including in the context of climate action41,42,43,44. Moreover, citizens in the upper segments of the income or wealth distribution should be made aware of their proportionally lower contributions to climate change mitigation. This awareness could activate advantageous inequality aversion, motivating them to contribute more to climate-friendly initiatives.

Climate policy should stringently incorporate social sustainability, the extent to which people perceive the contributions to climate mitigation of others as just, correct biases, and offer tailored financial instruments to reduce inequality—nationally and globally. Addressing both social inequality and inequality aversion is essential to achieving broad climate cooperation.

Responses