Effectiveness of flaxseed consumption and fasting mimicking diet on anthropometric measures, biochemical parameters, and hepatic features in patients with Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD): a randomized controlled clinical trial

Introduction

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is the most common chronic liver disease worldwide, with an estimated prevalence of 25% in general population [1]. The annual economic burden of MASLD in the United States is estimated to be 103 billion dollars [2]. MASLD has a wide pathological spectrum, from simple steatosis to steatohepatitis with varying degrees of fibrosis, to cirrhosis that may progress to liver failure and hepatocellular carcinoma [3].

Currently, no definitive medical treatment has been found for MASLD [3], while current studies suggest that the best treatment approach for MASLD is weight loss, which requires a combination of dietary modification and exercise to achieve and maintain this goal [3]. Besides the restriction of energy intake, some dietary interventions have shown promising effects on disease amelioration [4,5,6], or prevention [7,8,9].

Flaxseed with the Latin name of Linum usitatissimum is known as a functional food due to its beneficial nutritional properties [10]. In addition to omega-3, flaxseed has high fiber content, lignan, highly digestible protein, antioxidants and various phytoestrogens, which has made this seed an effective compound in the management of MASLD [11,12,13]. Suppression of hepatic glycolytic and lipogenic genes, stimulation of fatty acid oxidation, improvement of insulin sensitivity are among the benefits of flaxseed [11,12,13].

According to recent findings, the time of food consumption is an important factor besides the diet composition and the amount of energy intake in preventing obesity and its complications [14, 15]. Over the last decade, various fasting diets have been proposed. Time-restricted feeding (TRF), one of the most common of these diets, is a type of intermittent fasting that provides opportunities to eat at specific times during the day. For instance the 16:8 model includes an 8 h eating period followed by a 16 h fasting period [16,17,18]. The key feature of this diet is the so-called “metabolic switch”, which refers to the body’s preferential use of fatty acids and ketones derived from fatty acids instead of glucose from glycogenolysis [19]. This switch occurs when liver glycogen stores are depleted (usually after 12 h of fasting) and subsequently lipolysis of adipose tissue increases, which results in weight loss, decreased insulin resistance, and lower blood glucose levels [19].

Although benefits of flaxseed [11,12,13], and fasting mimicking diet (FMD) [16,17,18], per se, have been shown in managing MASLD risk factors, the benefit of combining the two is not clear. Therefore, the aim of this controlled clinical trial was to investigate the effect of the combination of FMD and flaxseed consumption compared to either of these interventions for the treatment of patients with MASLD.

Materials and methods

Recruitment and eligibility screening

The adult patients with MASLD, who referred to the Liver and Gastroenterology Clinics in Tehran were recruited. Liver steatosis was assessed using transient elastography (Echosens, Paris, France) [20], and patients with grade 2 or higher steatosis (CAP score ≥ 263) were included in the study. Patients with MASLD due to alcohol consumption (>10 g/d in women and >20 g/d in men) or hepatitis B or C were excluded. Other exclusion criteria were: professional athletes, pregnant or breastfeeding women, those taking anti-inflammatory medications or any other drugs known to affect liver function (even herbal preparations), the presence of gastrointestinal, cardiac, renal, pulmonary, autoimmune, thyroid diseases and severe metabolic abnormalities, and those who have previously had weight loss surgery or are on a weight loss program.

Study design and procedure

The present study was a randomized, parallel, open-label controlled clinical trial in patients with MASLD for 12 weeks. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of National Nutrition and Food Technology Research Institute, and written informed consent was obtained from the participants. The clinical trial protocol was registered at the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials (IRCT ID: IRCT20100524004010N36). The total planned sample size was 100 subjects with equal assignment to each intervention group (25 patients per group). Eligible participants were divided into four groups using a simple random method according to a table of random numbers, after stratification by gender and age. At the beginning of the study, all participants were given dietary modification recommendations [21]. The diet of all participants (in the four groups) were planned based on age, gender and BMI, and in order to coordinate the groups, the daily energy intake was determined to be 50% from carbohydrates, 20% from protein and 30% from fat. The control group only received dietary modification recommendations; the second group (flaxseed) was given 30 grams of flaxseed powder per day; the third group followed the FMD with 16 h of fasting, the fourth group (FMD + flaxseed) received the combination of two interventions (30 g of flaxseed and FMD with 16 h of fasting). Patients were followed closely every 4 weeks and charged with supplements. Adherence to the study protocol was assessed based on unused flaxseed. Patients were called every 7 days to remind the use of the supplements and to check probable adverse effects of the intervention. Additionally, 3 days of 24 h dietary recall were completed for patients to assess their dietary intakes.

Randomization

Given that gender and age can have significant effects on the study’s outcomes, stratified randomization and the permuted block randomization method with quadruple and binary blocks were used to ensure that these variables were distributed evenly among the groups. Using the www.sealedenvelope.com website, the quadruple block or double block were generated based on the sample size of 100 people. In fact, the researchers were unaware of the groups into which the patients were randomly assigned throughout the assessment phase (anthropometric measures and laboratory testing), as well as the allocation of participants into each group (intervention and control group) until the conclusion of the intervention. Also, the random sequence generated during the study was unpredictable.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on different dependent variables, and the largest sample size was obtained for CAP score. The study sample size was calculated based on the study of Yari et al. [12] with considering type one error (α) of 0.05 and type two error (β) of 0.20 to create a 25 dB/m difference in CAP score between groups. The sample size was calculated as 25 patients in each group, considering a 10% dropout.

Dietary intake and physical activity assessment

In this study, 3-day 24 h food recalls (2 weekdays and 1 weekend) were taken at the beginning and at the end of the 12th week of the study through face-to-face or via telephone interviews. Dietary intake data were analyzed by a nutritionist using Nutritionist IV nutritional software (First Data Bank, San Bruno, CA, USA) modified for Iranian foods [22]. Physical activity level at the beginning and end of the study was evaluated using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) that was defined by metabolic equivalents hour per day (MET-h/d) [23].

Measurement of anthropometric parameters

At the beginning, height was measured to the nearest 0.5 cm using a tape measure attached to the wall. Weight was also measured using a Seca digital scale with an accuracy of 100 grams while wearing light clothing. In addition, waist circumference (WC) was measured between the lower margin of the last rib and top of the iliac crest to the nearest 0.5 cm. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m2).

Measurement of biochemical parameters

After a 12 h fasting period, 10 ml of venous blood samples were taken from the subjects before and after the intervention. Plasma concentrations of alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), gammaglutamyl transpeptidase (GGT), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride (TG); fasting blood glucose (FBG) (Pars Azmoon Co, Tehran, Iran), insulin (Monobind Inc., USA); High-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) (Zellbio, Germany) were measured using the relevant kits, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) level was determined using the Friedewald equation [24]. Also, homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), to evaluate insulin resistance, was calculated using the following formula = fasting glucose (mg/dl) × fasting insulin (lU/ml)/405 [24]. Quantitative Insulin Sensitivity Check Index (QUICKI) was used to estimate insulin sensitivity and calculated according to the following formula = 1/[log plasma insulin (μU/ml)+log plasma glucose (mg/dl)] [25].

Liver steatosis and fibrosis evaluation

In this study, liver steatosis and fibrosis were measured by transient elastography using XL probe (FibroScan®, Echosens, Paris, France) at the beginning and at the end of the 12th week. Hepatic evaluation was performed by an experienced hepatologist with the same device.

Statistical analyses

In this study, statistical analysis was performed using the version 22 of SPSS software. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to determine whether the data followed a normal distribution. In this study, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and LSD (least significant difference) multiple comparisons were used to compare quantitative variables at the beginning of the study and also to compare the mean changes of these variables during the intervention among the four groups. In addition, the pair t-test or its non-parametric equivalent, Wilcoxon, was used to compare quantitative variables in each of the four groups before and after the intervention, and chi-square test was used to compare qualitative variables. The data were analyzed according to the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed to compare the mean of variables after adjusting for confounding factors (age, gender, etc.) and a p-value of ≤ 0.05 was considered as the significance level.

Results

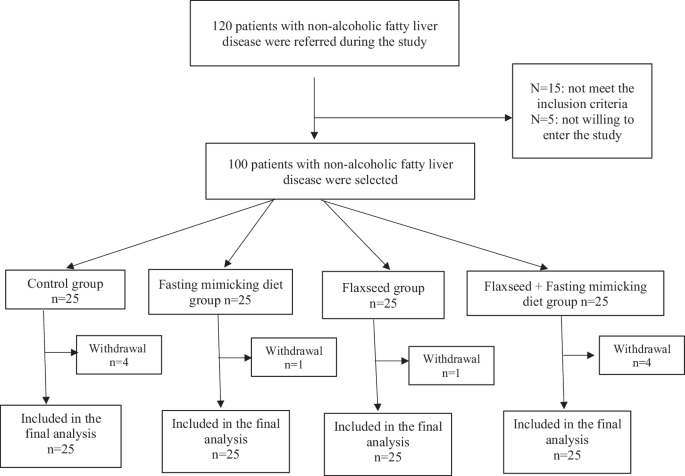

Among 120 participants who referred to the Liver and Gastrointestinal Clinics of Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, 100 participants who met the inclusion criteria were included in the study (four equal groups). Four of participants were excluded from our study due to low adherence to the sepecific diet or suplements (two participants) as well as personal reasons (two individulas). A consort flow chart of the trial design is shown in Fig. 1.

The consort diagram of participants in the study.

As it is shown in Table 1, there was no significant difference among the groups in terms of age and sex. Less than half of the participants were women (46%) and the average age and BMI of the participants were 45.15 ± 11.3 years and 31.49 ± 4.72 kg/m2, respectively. The difference between the groups was significant in terms of energy intake and macronutrients, and among the serum variables, TC, LDL and ALT showed a significant difference between the groups.

There was no significant difference in dietary intakes, except for cholesterol (P-value = 0.025), among the groups during the study (Table 2). The decrease in calorie intake during 12 weeks of intervention was significant in all four groups, except for the flaxseed + FMD group. Regarding macronutrients, the intake of carbohydrates and fat at the end of the study compared to the beginning of the study showed a significant decrease, except for carbohydrates in the flaxseed + FMD group and fat in the FMD group.

As it is presented in Table 3, weight and WC decreased significantly in all groups during 12 weeks. However, only the BMI change differed among the four groups significantly (P-value = 0.032). The most reduction of BMI was observed in the combination group; however, it was not significantly different from other interventions.

Table 4 shows the results of lipid, glycemic and inflammatory profiles in the groups before and after the intervention. During 12 weeks, TC, LDL and TG decreased significantly in all groups, except for TG in the control group. This difference between groups was significant only for TC (P-value = 0.028) and TG (P-value < 0.001).

The results of paired t-test showed that insulin and FBG decreased significantly in all three intervention groups, while insulin increased in the FMD group. Therefore, in this group, unlike the other three groups, insulin resistance increased and insulin sensitivity decreased, although it was not statistically significant. Other groups showed a significant decrease in insulin resistance and a significant increase in insulin sensitivity. The comparison of changes in glycemic parameters among 4 groups was significant, except for FBG.

The serum level of hs-CRP decreased significantly in all groups except the control, although this difference between groups was not significant. The most reduction of insulin, HOMA-IR, and hs-CRP was observed in the combination group; however, it was not significantly different from other interventions.

The serum level of liver enzymes in all groups, except the control, decreased significantly during the intervention. Also, the comparison of changes in the serum level of liver enzymes among the four groups indicated a significant difference in AST (P < 0.001) and GGT (P = 0.028) (Table 5). At the end of 12 weeks, steatosis (CAP) and fibrosis scores decreased significantly in all groups, and the highest decrease was observed in the combined intervention group. Although comparing the differences between the four groups did not show significant differences for CAP, fibrosis was significantly different between the groups (P = 0.032). The most reduction of CAP, and hepatic fibrosis was observed in the combination group.

Discussion

The present study is the first clinical trial to investigate the combined effects of the FMD and flaxseed powder on anthropometric measures, lipid and glycemic profiles, inflammation, liver enzymes, and hepatic steatosis and fibrosis in patients with MASLD. The findings of this study indicated significant differences in changes in BMI, liver fibrosis, insulin, HOMA-IR, QUICKI, TG, TC, AST, and GGT among the study groups; significant changes in TG, FBG, liver enzymes, and hs-CRP were seen in all three intervention groups compared to the control group. Although the combination of FMD and flaxseed, compared to each one alone, failed to show a significant difference, the most reduction of BMI, insulin, HOMA-IR, hs-CRP, hepatic steatosis, and fibrosis was observed in the combination group.

After adjusting all confounders, BMI changes showed significant differences among the studied groups. In all groups, during 12 weeks, a significant decrease in weight and waist circumference was observed; however, the difference among groups was not significant. These results are consistent with previous studies investigating the effects of FMD [17, 26], or flaxseed [12], individually. One of the main mechanisms of weight loss after FMD is metabolic changes. It has been suggested that FMD increases beta-hydroxybutyrate, which has anti-inflammatory effects, leading to improvement in metabolic parameters and obesity [27]. Moreover, the anti-obesity effects of flaxseed are attributed to its fatty acids and lignan content. Based on current evidence, eicosanoids derived from flaxseed have the ability to prevent adipose differentiation and induce apoptosis in pre-adipocytes, which might show inhibitory effects on obesity [28]. In our study, combination of these interventions reduced BMI more than each one alone; however, the difference was not significant. Thus, it seems that the synergistic effects of these interventions in short term duration is not significant.

In the present study, supplementing with flaxseed, adherence to FMD, and the combination of these two showed significant effects on the improvement of serum lipid profile components, except for HDL. Research results regarding the effects of flaxseed and FMD, each one alone, on lipid profile have shown previously [29,30,31].

In the present study, after 12 weeks of all three interventions, glycemic parameters showed a significant improvement, although the initial serum concentrations of FBG and insulin were almost within the normal range. Only, insulin increased in FMD group, which resulted in non-significant changes in HOMA-IR, and QUICKI. Previous studies have also reported promising results of flaxseed and FMD, individually, in improving glycemic parameters [19, 32]. Supplementation with flaxseed along with FMD reduced insulin resistance more than each one alone; however, the difference was not significant.

In the present study, supplementation with flaxseed, following FMD and the combination of the two significantly reduced hs-CRP, and the largest reduction was observed in the group of combined intervention, although no difference was found among the groups. The effects of flaxseed supplementation on the reduction of inflammatory factors such as TNF-α and CRP were frequently shown in previous studies [12, 33]. On the other hand, a meta-analysis on 16 clinical studies [34] showed that FMD and calorie restriction intervention program significantly reduced CRP (−0.024 mg/dl), with no significant effect on TNF-α and IL-6 levels. Furthermore, these analyzes showed that FMD more effectively reduced CRP levels (−0.029 mg/dl) compared to energy-restricted diets (−0.001 mg/dl).

Liver enzymes decreased significantly in all three intervention groups in this study. Similar results have been reported in previous studies by flaxseed supplementation or adherence to FMD in patients with MASLD [12, 17, 35]. In confirmation of the available evidence, in the current study, a significant decrease in fibrosis and steatosis was seen in all groups, and the largest decrease was related to the combination of flaxseed and FMD. In previous studies, flaxseed supplementation alone [12] showed promising results in inhibiting hepatic fat accumulation and significantly reduced fibrosis and steatosis scores. Similarly, adherence to FMD alone or along with other interventions has also shown a significant reduction in liver fat content [17, 36].

The following limitations of the study should be considered in interpreting the results. First, the study interventions, although randomized, were administered in an open-label manner. Second, the sample size of 25 subjects per each treatment group was small. Third, the trial duration was only 12 weeks. Fourth, we used ultrasound elastography (FibroScan) to measure hepatic steatosis and stiffness rather than assessing histopathology with liver biopsy. Baseline fibrosis scores were not indicative of significant fibrosis. Finally, Omega-3 intake did not increase at 12 weeks (Table 2) suggesting that the study participants were not adherent to the recommended flax powder consumption.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our data indicate that the combination of FMD with flaxseed consumption is not superior to any of these interventions alone in the management of MASLD. Further research with different duration, larger sample size, and different forms of flaxseed (oil and whole seed) are needed to find the optimum dosage and duration of the supplementation.

Responses