Effects of literature circles activity on reading comprehension of L2 English learners: a meta-analysis

Introduction

As one of the most complex language abilities for L2 learners, reading comprehension is an interactive and constructive process to interpret meaning from the text based on prior knowledge (Yamashita, 2022). As early as the 1940s, Davis (1944) identified nine component skills related to reading comprehension, laying the foundation for further exploration of this topic. Grabe (2009, 2014) provided a more encompassing explanation of reading comprehension by dividing the skills into lower-level processes, including word recognition skills, lexico-syntactic processing, and semantic processing of information, and higher-level processes that include forming the main idea, recognizing thematic information, building a summary understanding of the text, and developing a personal interpretation of the text. Proficient readers usually employ a combination of the component skills in the reading process.

However, the challenges faced by L2 learners in developing reading proficiency are multifaceted, encompassing linguistic, cognitive, and social factors, such as background knowledge and reading strategies (Boakye, 2011; McNeil, 2011), anxiety, L1 interference, and socioeconomic background (Soomro, 2022), syntactic and prosodic awareness (Park, 2017), decoding skills, and grammar and vocabulary knowledge (Choi & Zhang, 2021; Jeon & Yamashita, 2022; Zhang & Zhang, 2022), etc. As reading is affected by both reader-based and text-related factors determined by its dynamic nature (ÿlmez, 2016), reading achievement is related to both the quality and quantity of reading by students (Topping et al., 2007), as well as the use of strategies by instructors to construct meaning and generate a mental representation of the text for effective text comprehension (Friesen & Haigh, 2018). In terms of reading materials that determine the reading quality and quantity, a multitude of past studies have shown the effectiveness of integrating literature into L2 learning, as manifested in improving the four language abilities (Abdelrady et al., 2022; Ashrafuzzaman et al., 2021), contributing to esthetic, inferential, and intellectual skills (Regmi, 2022), enhancing learner motivation, as well as improving literary competence (Calafato & Hunstadbråten, 2024).

Regarding the effective method to integrate literature into L2 learning, previous research emphasized the importance of reading activities to promote effective reading by creating a cooperative learning environment and group discussions (Mubarok & Sofiana, 2017; Olaya & González-González, 2020). These activities can help compensate for cultural unfamiliarity and enhance understanding of the original text by focusing on cultural schema (Gürkan, 2012). Additionally, they can aid in improving comprehension and language development by promoting better understanding and linguistic construction (Jung & Révész, 2018). Furthermore, such activities can also support the development of reading skills, as well as boost vocabulary acquisition (Suk, 2017). Of the various reading activities, literature circles build a collaborative learning community for students to explore multiple features of the language, ranging from lexicogrammar to content knowledge through peer interaction and role scaffolding by instructors (Widodo, 2016).

Founded in the 1990s among K-12 students in America, literature circles were defined as “small, peer-led discussion groups” in which participants read the same stories, poems, and books (Daniels, 2002, p. 2). Over the past 30 years, this reading activity has developed into a powerful learning boom, transcending the K-12 classroom to the tertiary stage (Levy, 2011; Thomas & Kim, 2019) and extending beyond the L1 setting to the L2 language context (Kim, 2004). The effectiveness of this reading-discussion learning activity is likely attributed to its versatility to accommodate “a wide range of ages, circumstances, and needs” with the flexible basic tenets and assigned roles (Dalie, 2001, p. 85). Rooted in sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978) and transactional theory (Rosenblatt, 1978), literature circles provide a collaborative social environment for students to participate in meaningful discussions, engage with reading texts to create meaning, and share their own understanding, concerns, interpretations, and knowledge with peers. The magnetism of literature circle activities lies in their capacity to enact group dynamics that integrate collaboration, empowerment, and authenticity into the reading process (Dalie, 2001; Daniels, 2002).

The most distinctive feature of literature circles is the basic roles that give group members clearly defined tasks with cognitive and social purposes, including connector, questioner, literary luminary/passage master, and illustrator as the four basic roles that can be filled and expanded with optional roles (Daniels, 2002). The second defining feature of literature circles is the basic tenets that mark a successful literature circle, including (1) how to select reading materials, (2) forming small temporary groups, (3) different groups reading different books, (4) regular meetings for discussion, (5) drawing notes while reading, (6) students preparing discussion topics, (7) having open and natural conversations for discussion, (8) teacher assisting as facilitator, (9) incorporating teacher evaluation and self-evaluation, (10) ensuring the process is enjoyable, and (11) recombining new reading groups after each cycle (Dalie, 2001; Daniels, 2002; Furr, 2004).

As a highly developed form of collaborative learning movement that emphasizes group dynamics, literature circles not only enhance students’ understanding of what they read but also contribute to the cohesiveness and productivity of the classroom community (Daniels, 2002). Since their emergence, literature circles have been extensively employed in L1 teaching contexts for their benefits in improving various language skills (Carrison & Ernst-Slavit, 2005; Day & Ainley, 2008; McElvain, 2010; Thomas & Kim, 2019). With the increasing popularity of literature circles, their influence has extended to EFL and ESL settings to enhance learners’ second language acquisition as scaffolding. As a reading program, literature circles were commonly implemented in extensive reading as an effective tool to enhance L2 learners’ reading engagement and comprehension (Chou, 2022; Furr, 2004; Irawati, 2016; Widodo, 2016), potential bibliotherapy to engage EFL learners (Wang, 2024), and as a platform to foster critical reading and collaborative learning skills (Wafiroh et al., 2024). Moreover, literature circles were effective in enhancing the learning experience and communicative competence (Kim, 2003), reading enjoyment (Su & Wu, 2016), vocabulary enrichment (Hassan, 2018), speaking skills (Kaowiwattanakul, 2020), and increased motivation for literature reading (Imamyartha et al., 2020). Therefore, by integrating collaborative learning with meaningful text engagement, literature circles serve as a dynamic educational tool that fosters both cognitive and social growth, crucial for the language development of L2 learners.

Additionally, numerous existing meta-analyses have focused on the effects of interventions to improve L2 learners’ reading ability. Richards-Tutor et al. (2016) synthesis of published experimental studies from 2000 to 2012 indicated a moderate to large effect size for interventions aimed at improving the reading comprehension skills of beginners. The effect of reading interventions on English learning was further examined from outcomes such as reading accuracy, fluency, comprehension, and overall reading development (Ludwig et al., 2019), from basic reading skills development of students at risk for reading disabilities (Cho et al., 2021; Gersten et al., 2020), from writing performance (Graham et al., 2018), and reading comprehension and strategy ability in the whole classroom setting (Okkinga et al., 2018). Regarding specific reading activities, the effects of extensive reading on reading development have been a focus (e.g., Jeon & Day, 2016; Kim, 2012; Liu & Zhang, 2018). Furthermore, Fitton et al. (2018) reported a significant and positive effect of shared book reading on English learners’ outcomes. Nevertheless, there is a scarcity of meta-analytic research examining the overall effect of literature circles on L2 learners’ reading comprehension. Therefore, the current study aims to address the following research questions using a meta-analysis:

Question 1: What is the overall effect of literature circles on the reading comprehension of L2 English learners?

Question 2: To what extent are the effects of literature circles moderated by publication year, context, research method, treatment, outcome measures, and focus skills?

Methods

Search strategy

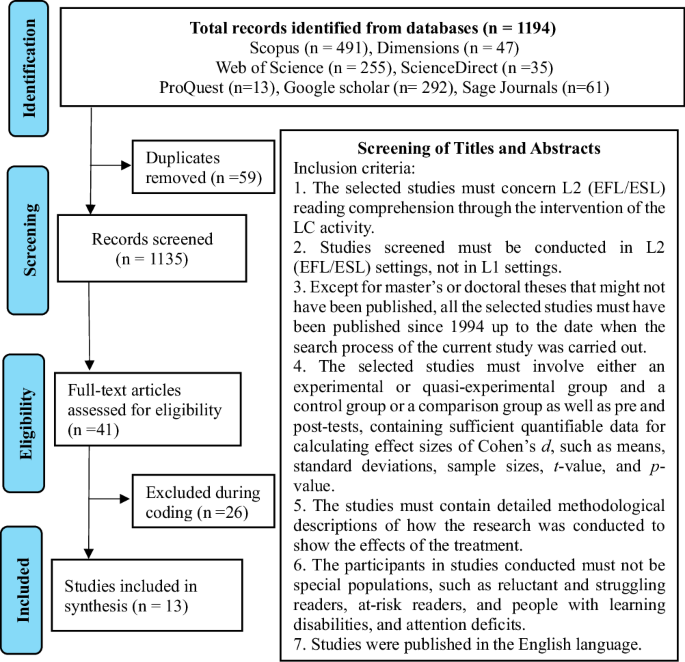

The present meta-analysis was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 statement for identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion processes (Page et al., 2021). It searched studies published from 1994, the year when literature circles were introduced and began to grow into a boom (Daniels, 2002), until June 10, 2024, to identify published experimental and quasi-experimental studies investigating the effects of literature circles on the development of reading comprehension in EFL and ESL settings. The keywords were identified before the search process, including “literature circles”, “reading circles”, “reading clubs”, and “reading comprehension”. The researcher then utilized a combination of keywords to locate relevant records across renowned databases of Scopus, Dimensions, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, ProQuest, Sage Journals, and Google Scholar. The search strategy, including identification, screening, eligibility and inclusion, was illustrated in the Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the search strategy.

Included studies and coding procedure

After a systematic search procedure, a total of 1194 records were identified across the seven databases, encompassing various sources such as books, book chapters, journals, reviews, conference proceedings, dissertations, and editorials, which were exported into the Mendeley reference management software for screening based on titles and abstracts. Finally, 13 primary studies were deemed eligible for synthesis and analysis based on the inclusion criteria, including three dissertations, one conference paper, and nine articles. All the eligible primary studies were conducted after the 2010s, although the study’s search scope extended to 1994. From the 13 primary studies, 15 sample studies were extracted, including one study involving a pre-post-test design and 14 sample studies utilizing a quasi-experimental control group design. Despite the inclusion of different study designs using independent groups and pre-post scores, the effect size (D) maintains the same statistical significance regardless of the substantive differences between the designs (Borenstein et al., 2009). Furthermore, due to the limited number of pre-post one-group designs, the data from the two different types of studies were combined as they function similarly in testing intervention effectiveness with comparable outcomes.

The sample studies were subsequently coded for demographic features, moderating variables, and outcomes. The coding scheme was informed by meta-analysis studies on L2 acquisition (e.g. Dalman & Plonsky, 2022; Jeon & Day, 2016; Lee et al., 2015; Plonsky, 2011) to compile information. Following a comprehensive reading of the sample studies and pilot coding, the finalized coding scheme comprised six sections, as presented in Table 1.

Each study was first identified for demographic data such as author, title, publication year, and type. The second category was context, including the language setting (EFL/ESL) that may influence learner beliefs, interactional behaviors, and comprehension (Sato & Storch, 2022; Taguchi, 2008), participants’ age and educational level that determine their cognitive and linguistic development (Bigelow & Watson, 2013). The third section examined the method concerning the research design, specifically whether participants were randomly assigned to different groups and whether reliability was reported.

For the treatment process, the following variables were analyzed: treatment provider (teacher or researcher), implementation environment (virtual or face-to-face), types of reading materials (literary works or other non-literary types), and mode of implementation (LCs as the reading course only or as a component of the reading course). Additionally, since the treatment duration for the sample studies was reported in different units of weeks, months, and semesters, this variable was classified into three categories (less than 1 month, 1–3 months, and 3–6 months) after examining the minimum, maximum, and average length of treatment across all sample studies. For the outcome measures section, the test-item formats were coded into two values (MCQ and Miscellaneous), as most studies only employed MCQ items, while others included True or False, Blank-filling, and Answering Questions in addition to MCQ. The test types were categorized into two values: standardized papers, which were drawn from established test papers, and teacher/researcher-generated papers, which were created from various sources without adhering to established guidelines.

Interrater reliability

The first-round coding was conducted by the researcher. To ensure reliability, all 13 primary studies were recoded by an expert in the field. Cohen’s Kappa (Cohen, 1960) statistic was used to evaluate the agreement between the two coders, resulting in a high inter-coder agreement of 0.92. The disagreements primarily revolved around determining treatment duration and test-item formats. To address these discrepancies, the coders revisited the guidelines for treatment duration and the different test formats to ensure consistency. After careful consideration and negotiation, the coders resolved all disagreements and reached consensus.

Statistical analysis

Calculation and interpretation of effect size

For the current study, Comprehensive Meta-Analysis (CMA) 3.0 software was used to implement the meta-analysis for its many user-friendly advantages in systematically summarizing the results of studies (Brüggemann & Rajguru, 2022). Meta-analysis is a research method used to aggregate effect relationships from multiple studies, which may be evaluated in odds ratios, risk ratios, risk differences, correlations, and standardized mean differences, of which standardized mean differences d and Hedges’ g are commonly used in social sciences meta-analysis to compare the differences between two groups (Borenstein & Hedges, 2019). In this study, Cohen’s d (Cohen, 2013) was used as an appropriate effect-size estimate, as is a customary practice within L2 research (Plonsky, 2011; Norris & Ortega, 2000). The formula for calculating the standardized mean difference between two independent groups and pre-post scores or matched groups is expressed similarly (Borenstein & Hedges, 2019):

But the Swithin (pooled standard deviation) for between groups and pre-post scores comparison is different and expressed as follows:

In the current meta-analysis, only one primary study employed a pre-post one-group research design, and twelve studies involved the comparison between two independent groups. With the sophisticated features of CMA, the outcomes between two groups and within one group can be analyzed efficiently, alongside the program’s capabilities for estimating effect sizes in subgroups, assessing publication bias and sensitivity, and generating high-resolution plots for data analysis.

The benchmark for interpreting effect sizes from standardized mean differences proposed by Cohen is 0.2 (small), 0.5 (medium), and 0.8 (large). However, Cohen’s benchmark has been deemed a potentially misleading index for interpreting relationship magnitudes within social science disciplines and specific domains (Valentine & Cooper, 2003) and tends to underestimate experimental effects in L2 research (Oswald & Plonsky, 2010). In recent years, the scale for interpreting effect-size estimates presented by Oswald and Plonsky (2010) has become prevalent (e.g., Choe et al., 2020; Jeon & Day, 2016) within the SLA subdiscipline. Therefore, this study adopted the SLA standards for effect sizes, where d = 0.40 represents a small effect, d = 0.70 indicates a medium effect size, and d = 1.00 signifies a large effect size for between-group contrasts.

Results

Demographic features of the sample studies

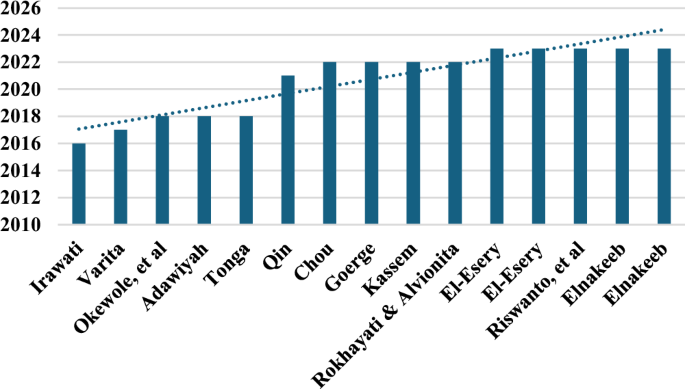

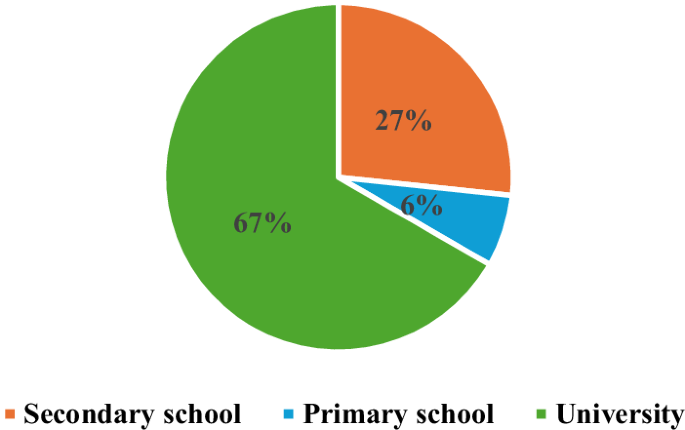

The study analyzed 15 sample studies (13 primary studies) comprising 899 participants. The sample included 10 studies from journal articles, four from dissertations, and one from a conference paper. Although literature circles were initially practiced in 1994 in America with K-12 L1 learners, their implementation in L2 learning (EFL or ESL) gained momentum after the 2010s, with 67% of the sample studies occurring after the 2020s, compared to 33% in the 2010s (Fig. 2). Among the 15 sample studies, 13 (87%) were conducted in an EFL context compared to 2 (13%) in ESL settings. While literature circles were originally utilized among elementary school students, the descriptive results indicated a greater application of this reading program in universities (67%) to enhance the reading proficiency of tertiary-level students (Fig. 3). Regarding implementation modes, five sample studies (33%) were conducted virtually, while 10 (67%) employed face-to-face instruction. Concerning reading materials, six sample studies (40%) utilized literary texts such as stories or novels as language input, whereas nine (60%) employed textbooks or expository texts. To assess intervention outcomes, multiple-choice questions were utilized in all studies, with eight (53%) studies employing them as the sole testing format, and seven (47%) combining them with other formats such as true-or-false questions, matching, blank-filling, and essay questions.

Year of publication of sample studies.

Distribution of educational levels of the sample studies.

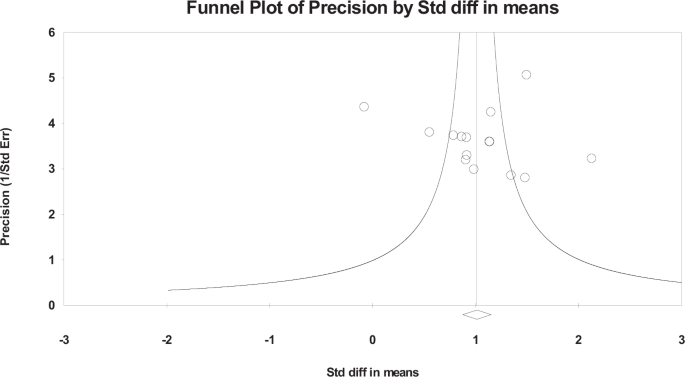

Publication Bias

To assess the presence of publication bias, a funnel plot and Classic fail-safe N test were implemented. The funnel plot depicts scatter plots of treatment effects estimated from individual studies (Sterne & Harbord, 2004). The horizontal axis shows the standard difference in means, while the vertical axis indicates precision (inverse of the standard error). The funnel shape illustrates the expected distribution of studies: those with higher precision (lower standard error) tend to cluster closer to the mean difference (near the funnel’s top). Results from smaller studies scatter more widely at the graph’s bottom, with the spread narrowing among larger studies. The scattered points within the funnel denote individual studies. Without bias, the plot resembles a symmetrical, inverted funnel. Based on Fig. 4, the plot appears symmetrical. The data points concentrate more densely near the funnel’s bottom (where precision is lower), gradually dispersing as precision increases. This symmetrical pattern suggests minimal publication bias.

Funnel plot of precision by effect sizes.

The Classic fail-safe N test determined the number of null effect studies needed to elevate the p-value associated with the mean effect above the alpha level (α = 0.05). The test revealed that 792 additional studies would be necessary to nullify the overall d obtained in this meta-analysis. When the fail-safe N is substantially large compared to the observed studies, the meta-analysis results are robust against publication bias (Rothstein et al., 2005). Since only 15 sample studies were included in the current analysis, it is improbable that 792 studies with nil-null results were excluded due to publication failure or researcher oversight during the literature review. Thus, these findings remain uncompromised by publication bias.

Results of meta-analysis

Overall effects of literature circles and test of heterogeneity

The major goals of a meta-analysis are to test whether the results of studies are homogeneous and to assess the effect’s magnitude of an intervention across included studies (Huedo-Medina et al., 2006). Table 2 shows the summary effect with both the fixed-effect model and random-effects model and the heterogeneity assessment. The fixed-effect analysis assumes that the true effect is identical across all studies, while the random-effects analysis assumes that the summary estimate represents a random sample of effect sizes observed (Borenstein et al., 2009). The selection of the statistical model depends on the assessment of the presence or absence of true heterogeneity by using the Q test, which is computed by summing the squared deviations of each study’s effect estimate from the overall effect estimate and follows a chi-square distribution with k-1 degrees of freedom (k = number of studies) under the hypothesis of homogeneity among the effect sizes (Huedo-Medina et al., 2006). As shown in Table 2, the homogeneity test has reached statistical significance (Q = 49.47, df = 14, p < 0.05), indicating that the homogeneity assumption that all studies evaluate the same effect size is rejected, and there is more variability across effect sizes than would be expected based on sampling error.

Moreover, to further assess the extent of heterogeneity, the I2, which can quantify the magnitude of heterogeneity as a percentage of total variation, is a more insightful index (Borenstein et al., 2009; Huedo-Medina et al., 2006). The benchmarks for I2 were 25%, 50%, and 75%, representing low, moderate, and high degrees of inconsistency in the studies’ results (Higgins et al., 2003). The percentage of I2 for the current meta-analysis was 71.70%, indicating a moderate to high degree of heterogeneity among the 15 studies, so random-effect assumptions were appropriate to estimate the overall effect sizes in this study.

Therefore, the results of the random-effects size were estimated to answer the first research question, which addresses the overall effectiveness of literature circles on reading comprehension of L2 English learners. The overall effect size was 1.035, indicating that the treatment of using literature circles was indeed effective in improving the reading comprehension of L2 learners (p < 0.05), and there is 95% certainty that the true effect is far from zero, falling anywhere within the large effect range (between 0.77 and 1.30). According to the suggested effect sizes by Plonsky and Oswald (2014) in L2 learning, the overall effect size of the literature circles treatment on the reading comprehension of L2 English learners is high in strength.

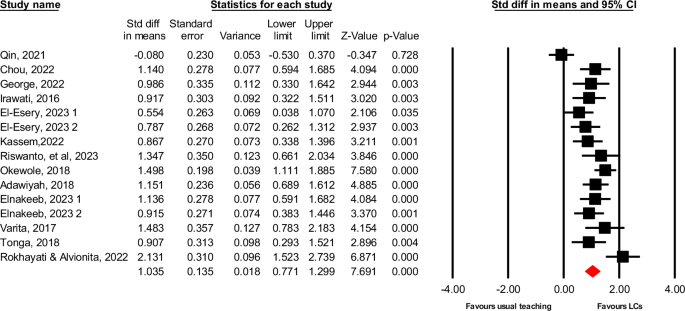

To better interpret the statistics in context, the forest plot is utilized in this study (Borenstein et al., 2009). In Fig. 5, the forest plot displays the effect sizes of individual sample studies. The diamond at the bottom represents the overall pooled effect from the included sample studies, with the width of the diamond indicating the confidence interval for the overall effect. Each included study is depicted by a line above the diamond, with the midpoint of the box representing the point estimate of the effect size. The width of each study line extending through the box shows their confidence intervals, reflecting the likelihood that the true effect in the population lies within that range. The vertical line corresponding to the value 0 represents the line of no effect. As evident from the plot, both the pooled point estimate and the 95% confidence interval lie entirely to the right of the line of no effect, indicating a statistically significant difference in the outcomes. In terms of individual sample studies, all the point estimates lie to the right of the no-effect line except for the first study (Qin, 2022), suggesting that the difference in outcome between the LCs intervention and comparator is not statistically significant in only one sample study (7%), while the intervention appears effective in the majority of studies (93%).

Forest plot illustrating the treatment effects of included studies.

Sensitivity

Sensitivity analysis is an important part of research synthesis in assessing robustness and bounding uncertainty (Cooper et al., 2019). Sensitivity analysis is an evaluation method that determines whether the conclusions of an analysis are robust when the criteria for including studies are changed, or when some assumptions are changed while performing the analysis (Borenstein et al., 2009). This sensitivity analysis, conducted with CMA by removing different studies in each pass, repeatedly shows that regardless of which study is removed, the pooled effect size does not change substantially (0.96 ~ 1.12). This indicates that the result is not sensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of specific studies, suggesting that the overall conclusions drawn from the meta-analysis are trustworthy.

Results of moderator analysis

Quantifying the extent of heterogeneity not only affects the decision to adopt the appropriate model but also necessitates the examination of the association between the heterogeneity and the characteristics of the studies (Valentine & Cooper, 2003). In other words, there is evidence for additional systematic sources of variability that need to be explained by potential moderator variables. To assess which variable source was a significant moderator of the variance in the observed effect sizes, a mixed-effects model was employed (Rodriguez et al., 2023) to achieve answers to the second research question from the aspects of identification, context, method, treatment, and outcome measures.

Identification

Despite the wide range of search studies traced to the 1990s, the studies eligible for synthesis in this current study covered only the period of the 2010s onwards. The 15 sample studies were grouped into two periods of publication, with five studies in the 2010s and 10 in the 2020s. As Table 3 shows, the studies in the 2010s had a large effect size (d = 1.23, k = 5) compared to the medium effect size in the 2020s (d = 0.96, k = 10), indicating a decrease in effect size and an increase in the number of studies using literature circles in English reading development after the 2020s. However, the difference between the two groups shows that the publication year is not a significant moderator of the variance in the observed studies (Q = 1.47, p > 0.05).

Context

Table 4 displays the analysis of moderating variables in the context of language setting and educational level. Even though the age group was also coded, since they have the same values corresponding to the educational level, the analysis was not performed to avoid repeated analysis. In terms of language settings, the ESL setting has an obviously larger effect (d = 1.31, k = 2) than studies in the EFL settings (d = 1.00, k = 13), but the difference between the two settings was not statistically significant (Q = 1.22, p > 0.05), indicating that EFL settings provide language learners a contextual environment as effective as the ESL setting. However, a significant difference was found across the educational level or age group (Q = 6.78, p < 0.05), indicating that the educational stage is a significant moderator causing heterogeneity across the included studies. The results revealed that the effect of the LCs decreases as the learners’ age grows and the number of studies included increases, with the studies among university students displaying the lowest effect size (d = 0.93, k = 10). Nonetheless, more relevant studies are needed to confirm the results due to the sharp difference in the number of studies included in each group.

Method

Related to the variable of whether the participants were assigned randomly into groups, only five out of the 15 sample studies have reported random assignment, and 10 have conducted treatment with intact classes. Table 5 demonstrates the studies without random assignment reported a higher effect size (d = 1.13, k = 10) compared to those with random assignment (d = 0.85, k = 5). The sample studies reporting instrument reliability achieved a medium effect size (d = 1.00, k = 7) compared with those that did not report instrument reliability (d = 1.10, k = 8). However, there were no statistically significant differences found in both the methods of random assignment (Q = 1.43, p > 0.05) and reliability reported (Q = 0.15, p > 0.05) to influence the effect of the LCs.

Treatment

Regarding the moderator analysis across treatment (Table 6), there is no statistically significant difference between the two treatment providers (Q = 0.32, p > 0.05), but there is a more significant effect size of studies with the researcher as treatment provider (d = 1.25, k = 4) than with the teacher as provider (d = 0.96, k = 11). The reading program of LCs is similarly effective whether it is conducted online (d = 1.05, k = 5) or face-to-face (d = 1.03, k = 10), but no significant difference was found between the two learning environments to moderate the variability of included studies. Although literature circles primarily adopt literary works as reading materials to prompt discussion, the analysis shows a more significant effect size from studies using miscellaneous genres (d = 1.07, k = 9) than studies using only literary texts (d = 0.99, k = 6). Like the learning environment, the variable of reading materials is not a significant moderator. Additionally, no statistical difference was found among the length of treatment (Q = 5.94, p > 0.05), but the studies with a duration of less than a month surprisingly achieved the highest effect size (d = 1.24, k = 7) than the studies with a duration of one to three months (d = 0.86, k = 6) and with three to six months (d = 1.02, k = 2), indicating that the length of treatment does not influence the effectiveness of literature circles as a tool to improve the reading comprehension of L2 English learners.

Outcome measures

The next variable examined is the types of test items that could potentially moderate the effect of literature circles. Table 7 shows that the studies adopting multiple-choice-question items have an aggregated large effect size (d = 1.31, k = 8) compared with the medium effect size from studies that use multiple test formats (d = 0.71, k = 7). The analysis also shows that the test-item format is a significant moderator to the variability in the overall effect size from the observed studies (Q = 7.65, p < 0.05).

Outcomes

The last moderator variable to be examined is the comprehension skills to develop through literature circles. Table 8 shows no statistically significant difference between reading comprehension and vocabulary acquisition (Q = 0.77, p > 0.05). The effect size on reading comprehension was large (d = 1.066, k = 13) compared with the moderate effect size on vocabulary acquisition (d = 0.85, k = 2).

Discussion

The current meta-analysis sets out to explore the overall effects of literature circles on the reading comprehension of L2 English learners and proceeds to examine the potential moderating factors that may influence the effects regarding publication year, context, research method, treatment, and outcome measures. Based on the research questions, this section aims to provide a deeper understanding of the results within the context of existing knowledge and offer insights into the implications of the findings.

The research findings show that the overall effect of the literature circles on reading comprehension was large (d = 1.04) based on the benchmark set by Oswald and Plonsky (2010), confirming the effectiveness of this reading intervention in improving the reading comprehension abilities of L2 learners. This effect size from the study was comparable to the findings of a previous meta-analysis that synthesizes the effects of reading interventions on English learning. For example, a similar large effect of reading interventions on reading accuracy (d = 1.221) and reading fluency (d = 0.802), but a moderate effect on reading comprehension (d = 0.499) (against Cohen’s criteria) was obtained in the study of Ludwig et al. (2019), along with moderate-to-large effect sizes (ES range, 0.58–0.91) for interventions targeting beginning reading skills, and also moderate-to-large effect sizes (ES range, 0.47–2.34) for interventions targeting reading or listening comprehension (Richards-Tutor et al., 2016). The effect was much larger than the small effect size (d = 0.39) in the synthesis of reading interventions for primary-grade students (Gersten et al., 2020), a small effect size of reading strategy interventions on reading comprehension (d = 0.186 for standardized test and d = 0.431 for researcher-developed test) and a medium effect size (d = 0.786) on reading strategic abilities (Okkinga et al., 2018), and a moderate effect size (d = 0.653) of reading interventions on reading outcomes for K-12 ELLs (Cho et al., 2021), as well as a similar moderate effect size (d = 0.91) of L2 reading strategy intervention on reading comprehension (Yapp et al., 2021).

The large effect size of the current study supported the previous research findings that guided reading interventions significantly improved reading comprehension and reading (e.g. Nayak & Sylva, 2013; Lara-Alecio et al., 2012), reading attitudes, and vocabulary learning (Chen et al., 2013), reading rate, and vocabulary acquisition (Suk, 2017) of L2 learners. The study results further highlighted the advantages of incorporating literature circles in L2 reading, supporting previous research that indicates these circles can enhance students’ content knowledge and language learning (Widodo, 2016), improve reading comprehension (Fitri et al., 2019; Varita, 2017), foster an understanding of literary texts and self-regulated language learning skills (Kassem, 2022), develop text analysis skills (Karatay, 2017), and boost students’ self-efficacy in reading comprehension (Wati & Yanto, 2022).

The second primary objective of the current study is to identify potential variables that moderate the effect of literature circles on reading comprehension. The research findings from the aspect of identification showed the interest in applying LCs has extended immensely from L1 settings to L2 learning over the years since 2010, but the effect size of this activity in L2 settings has decreased when compared to studies in the 2010s (d = 1.23) with the 2020 s (d = 0.96), even though the number of studies has doubled. However, similar to the burgeoning interest in LCs that originated in America (Daniels, 2002), the influence of this program has begun to gain momentum and has been investigated both quantitatively (Chou, 2022; Huljanah et al., 2020; Karatay, 2017) and qualitatively in both EFL and ESL settings (e.g. Nurhadi & Anggrarini, 2022; Dalie, 2001; Su & Wu, 2016), indicating that LCs are a promising pedagogical approach for improving reading comprehension in language acquisition.

In terms of the context of language setting and educational level, the research findings revealed that educational level or age group is a significant moderator (Q = 6.78, p < 0.05), while the difference between EFL and ESL did not cause variability across the included studies (Q = 1.22, p > 0.05). The results concerning language settings are consistent with previous research comparing reading comprehension in EFL and ESL settings (Taguchi, 2008) and reading strategy awareness (Karbalaei, 2010), but differ from previous research regarding learner beliefs and behaviors in which EFL learners performed better (Sato & Storch, 2022), and pragmatic awareness where ESL learners increased more significantly (Schauer, 2006). The results also differ from the findings of previous meta-analyses that indicate the EFL setting provides more positive effects than the ESL setting in L2 aspects such as extensive reading (Jeon & Day, 2016), listening strategy instruction (Dalman & Plonsky, 2022), and phonemic awareness (Choe et al., 2020). However, this finding helped enhance the effectiveness of LCs in improving reading abilities in both L1 and L2 settings (Hsu, 2004; McElvain, 2010; Thomas & Kim, 2019).

The research findings regarding the variable of educational level as a significant moderator were consistent with previous meta-analyses in L2 learning; younger learners benefit more from interventions (Cho et al., 2021; Choe et al., 2020; Graham et al., 2018) than older learners (Dalman & Plonsky, 2022; Jeon & Day, 2016), despite the overwhelming number of included studies involving university students. This decrease in effect size as educational levels increase may be attributed to the collaborative nature of literature circles that evolve from elementary school and rely on group dynamics (Daniels, 2002). Nonetheless, this reading activity has also been increasingly used in college classrooms as an apparatus for interaction with a text and meaning construction (Levy, 2011).

The methodological variables regarding whether the participants are randomly assigned into groups and whether the reliability of the instruments is reported also did not significantly affect the effect size of literature circles. Of the 15 sample studies, only 5 (33%) have used random assignment, and 7 (47%) have reported instrument or interrater reliability. However, contrary to the findings in L2 learning (e.g., Dalman & Plonsky, 2022; Plonsky, 2011), the studies committed to these methodological rigors obtained moderate effect sizes compared to those studies conducted without these features reported. This result may testify that the effect of an intervention is the outcome of a series of factors, such as time, resources, effort, and the degree of experimental manipulation (Plonsky & Oswald, 2014), with methodological rigors accounting for less overall effect.

Of the moderating effects concerning the treatment procedures, none of the variables constituted a significant moderator, indicating that literature circles are effective regardless of the provider, learning environment, material type, and length of treatment. The results regarding the variable of treatment provider and duration aligned with the findings of previous meta-analyses (Cho et al., 2021; Dalman & Plonsky, 2022; Jeon & Day, 2016), contrary to the expectation that a longer duration of treatment provided by instructors can result in more differentiating effects. The findings regarding the online and face-to-face learning environments were contrary to previous investigations by Alhamami (2022), indicating students hold a more positive attitude toward face-to-face environments than in online language settings; by Kelly et al. (2007), noting that the delivery method can significantly affect learners’ skills in analyzing topical themes and categories; and by Bi et al. (2023), showing that e-learning groups outperformed face-to-face groups in English learning and vocabulary retention rates. However, the result aligned with the findings by Bozkurt & Aydin (2023), in which no significant difference was found between the two delivery methods regarding collaborative instruction outcomes on learners’ speaking anxiety, and by Read et al. (2011), highlighting that online learning of L2 can be as effective as face-to-face learning.

In terms of the types of reading materials, although literature circles were literature-centered (Daniels, 2002), the current study indicated that there was no statistically significant difference between literary texts and mixed types in impacting the effect of literature circles on L2 learners’ reading comprehension. The result differed from past research, which suggested that literary texts can tremendously improve students’ abilities such as critical thinking (Khatib & Alizadeh, 2012), inferring ability (Khatib & Alizadeh, 2012), cultural awareness, and language acquisition (Bérešová, 2014). Aligned with the claim that literature circles provide a platform to integrate both literary and non-literary texts (Stien & Beed, 2004), the current study did support the principle of LCs allowing students to select their reading materials (Furr, 2004; Shelton-Strong (2012)).

In addition, in line with the results of previous meta-analyses in this domain (Chang, 2024; Dalman & Plonsky, 2022), the current research findings indicated that different outcome measures can significantly moderate the research results. The effect size for the test type of MCQ was larger (d = 1.31) than the test type using mixed testing methods (d = 0.71) such as MCQ, true-or-false, blank-filling, and essay questions. This result further corroborated the research findings that students perform better in receptive tests than in productive tests (Perez et al., 2013); MCQ was advantageously easier than open-ended questions (Polat, 2020); and students can achieve substantially and significantly higher scores with MCQ (Currie & Chiramanee, 2010). However, this also indicated that the types of testing formats in language evaluation can play an important role in measuring the effect of interventions, thus, deserving further investigation concerning the difficulty level and discriminating power of the test formats.

Conclusion

This meta-analysis examined the overall effect of literature circles in improving learners’ reading comprehension, as well as the moderating factors that influence the reading intervention program’s outcomes. The results revealed a large effect size from the sampled studies, confirming LCs’ effectiveness in both EFL and ESL learning. Moreover, among various moderating variables, only the learners’ education level/age group and test formats significantly affected the results.

The findings of the current research contribute valuable insights to the existing literature on literature circles’ effectiveness in L2 reading. It also carries practical and theoretical implications. As a valuable tool enabling students to engage in collaborative reading, literature circles create an immersive learning experience for text encounters and viewpoint sharing (Imamyartha et al., 2020), thus providing a transformative pedagogical approach that combines diverse reading texts and collaborative learning within a scaffolded framework. Furthermore, as a highly evolved component of the collaborative learning environment (Daniels, 2002) rooted in transactional theory (Rosenblatt, 1978) and sociocultural theory (Vygotsky, 1978), the large effect size of this meta-analysis provided further evidence of improving reading comprehension through collaborative learning, peer interaction, and meaning construction, demonstrating these theories’ practical application in L2 learning contexts. Consequently, building on these findings, educators and policymakers can leverage literature circles’ effectiveness by prioritizing reading activities’ integration to create a more engaging and supportive atmosphere, empower students, and ultimately enhance language proficiency.

However, several limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, this meta-analysis included only published articles for synthesis, omitting unpublished works, which may introduce publication bias and overestimate the true effect size based on a biased sample (Rothstein et al., 2005). The second limitation is the small number of included L2 setting studies, excluding numerous empirical studies from L1 settings, which, according to Borenstein et al. (2009), may yield inaccurate point estimates and confidence intervals. Finally, despite identifying educational level/age group and test formats as significant moderators affecting outcomes, caution is necessary when generalizing these findings due to small sample sizes and the fact that educational intervention effectiveness typically results from comprehensive factors working together rather than specific elements alone.

These limitations suggest recommendations for future studies. While the current meta-analysis demonstrates LCs’ overall effectiveness in improving reading comprehension, future research should: (1) investigate this intervention’s synthesized effect in developing other language abilities such as speaking, writing, social skills, and critical thinking; (2) incorporate unpublished studies and L1 setting research to assess literature circles’ true effect size in language learning more objectively; (3) employ alternative literature review methods such as network meta-analysis and systematic review to provide a more comprehensive assessment of LCs in language learning.

Responses