Effects of nitrogen vacancy sites of oxynitride support on the catalytic activity for ammonia decomposition

Introduction

Hydrogen has emerged as a crucial alternative energy carrier in the face of progressing global warming caused by the extensive consumption of fossil fuels and subsequent CO2 emissions1. However, serious problems exist in the storage of liquid hydrogen, such as boiling of the liquid and the requirement of extremely low liquefaction temperatures (–259 °C)2. Ammonia has garnered attention as a hydrogen carrier because of its high hydrogen storage density and ease of liquefaction under mild conditions. To realize the practical utilization of ammonia as a hydrogen carrier, the development of an efficient process for hydrogen production via catalytic ammonia decomposition is highly important. The catalytic activity for ammonia decomposition over transition metal catalysts is governed by the interaction between the transition metal surface and ammonia molecules, which results in a volcano-shaped relationship, and Ru has the optimum activity according to this relationship. Ni-based catalysts have been investigated as alternatives to precious metal Ru catalysts for ammonia decomposition. However, the catalytic activity of Ni catalysts is significantly lower than that of Ru catalysts, even though the adsorption of nitrogen on Ni can be enhanced by the formation of alloys or electron donation from the catalyst support3,4,5. As a result, high reaction temperatures are required to achieve high ammonia decomposition activity. Therefore, the development of Ni-based catalysts that are highly active at low reaction temperatures is strongly desirable.

Recently, it has been reported that nitride-based materials promote the activity of nonnoble metal catalysts for the decomposition of ammonia6,7,8,9. For example, composite catalysts of alkali or alkaline earth metal imides/amides and transition metals (TMs) are efficient for ammonia decomposition. In particular, the catalytic performance of TM-Li2NH composite catalysts is comparable to or greater than that of conventional Ru catalysts such as Ru/carbon nanotubes and Ru/MgO9. In these catalysts, Li2NH acts as an NH3 transmitting agent, which enhances the bonding between the TM and nitrogen. However, these alkali or alkaline earth metal imides/amides are very sensitive to moisture, which leads to deactivation after exposure to air. We recently developed an air-stable oxynitride support of perovskite BaTiO3-xNy with a hexagonal structure (h-BaTiO3-xNy) that promotes the activity of nonnoble metal catalysts such as Ni, Fe, and Co for ammonia decomposition10. The chemical composition of BaTiO3-xNy was determined to be BaTiO2.00N0.34ϒ0.66, where ϒ denotes an anion vacancy site. The BaTiO3-xNy catalyst thus allows many anion vacancy sites in the lattice and promotes ammonia decomposition via a lattice N- and/or anion vacancy-mediated Mars–van Krevelen-type mechanism. The catalytic performance of Ni/BaTiO2.00N0.34ϒ0.66 is comparable to that of a Ca-imide-supported Ni catalyst and remains unchanged even after exposure to water10. This oxynitride was demonstrated to be a useful catalyst support for ammonia decomposition10; however, the role of the oxynitride support in ammonia decomposition has yet to be clarified owing to a lack of studies.

In this study, the catalytic performance of Ni/BaTiO2.00N0.34ϒ0.66 (hereafter denoted as Ni/BaTiO2.00N0.34) was compared with that of other oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts to clarify the role of the oxynitride support in the ammonia decomposition reaction. Some perovskite oxynitrides have been well studied as photocatalysts for the water splitting reaction because of their high stability in water and efficient light absorption ability11,12. BaTaO2N and LaTiO2N were selected as oxynitride catalyst supports because they have high nitrogen concentrations and are stable in water. The role of the oxynitride support in the catalytic cycle was investigated experimentally and computationally.

Results and discussion

Figure 1a shows the ammonia decomposition activity of Ni supported on various perovskite oxynitrides as a function of reaction temperature. Ba5Ta4O15 and La2Ti2O7 were also tested as references. These oxides were also used as starting materials for the synthesis of BaTaO2N and LaTiO2N. The oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts showed greater activity than the oxide-supported Ni catalysts did, and 2.5–18 times greater catalytic performance was obtained for the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts at 500 °C. The oxynitrides without Ni loading exhibited low ammonia conversion (<15%), even at a reaction temperature of 650 °C (Fig. S1), which is much inferior to the catalytic performance of the Ni-loaded oxynitrides. The Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 catalyst exhibited the highest ammonia decomposition activity among the catalysts tested. The apparent activation energy (Ea) for ammonia decomposition over the oxynitride-based catalysts was in the range of 69–76.2 kJ mol–1, which is relatively lower than that for the oxide-based catalysts (83.8–100.2 kJ mol–1). This result suggests that the use of an oxynitride as a support changes the reaction pathway compared to that of oxide-based catalysts. Metal oxide supports with alkaline earth or rare earth elements effectively promote the decomposition of ammonia over supported TM catalysts13,14,15,16,17. However, the promotion effect is much more prominent for oxynitride supports that consist of the same elements as the oxide supports, except for nitrogen. As shown in Fig. S2, the ammonia decomposition activities of the Ni-loaded oxynitrides were repeatedly confirmed, with a standard deviation of 5%, demonstrating the high reproducibility of the oxynitride-based catalysts.

a Temperature dependence of NH3 conversion during ammonia decomposition over various Ni catalysts. The black dotted line represents the equilibrium conversion rate of ammonia decomposition. b Time course of ammonia decomposition over Ni-loaded oxynitride catalysts. The values in parentheses indicate the operating temperature.

The stability of these oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts was evaluated at similar NH3 conversion levels (Fig. 1b). The catalytic activities of Ni/BaTaO2N and Ni/LaTiO2N decreased slightly during the first 10 h and subsequently became constant. In contrast, the Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 catalyst exhibited stable activity during the entire test period. Furthermore, the catalytic activities of Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 in the second run were almost identical to the initial activities in all the temperature ranges (Fig. S3). The crystal structure of the oxynitrides remained almost unchanged after the ammonia decomposition reaction, with only Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 exhibiting slight peak broadening (Fig. S4). However, there is no significant difference in the N2 desorption behavior between the Ni/h-BaTiO3-xNy catalysts before and after ammonia decomposition (Fig. S5), which indicates that the composition of the h-BaTiO3-xNy support remains unchanged during the reaction. These results suggest that the crystallinity of h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 slightly decreases because of surface reconstruction during the ammonia decomposition reaction through a nitrogen vacancy-mediated reaction mechanism. This surface reconstruction may lead to the aggregation of Ni particles on h-BaTiO2.00N0.34, which accounts for the slight decrease in catalytic activity with increasing reaction time.

Structural characterization was conducted to elucidate the difference in the ammonia decomposition activity, as shown in Fig. 1. The Brunauer‒Emmett–Teller (BET) surface areas of the samples used in the experiments are summarized in Table S1. These results indicated little difference between the surface areas of different samples. Structural modifications of the Ni nanoparticles caused by interactions with the support were investigated via X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements. Figure 2a shows the Ni K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra of the tested catalysts. Although the Ni in Ni/LaTiO2N was slightly oxidized, the other catalysts were composed of only metallic Ni particles. The partial oxidation of Ni in the Ni/LaTiO2N catalyst is attributed to the small Ni particle size (Table S2)18, i.e., the fraction of the Ni-support interface was larger for Ni/LaTiO2N than for the other catalysts. Fourier transforms of the extended XAFS (EXAFS) spectra (Fig. 2b) indicated that most samples presented signals associated with Ni–Ni bonds with a similar intensity at 2.2 Å, except for Ni/LaTiO2N. As summarized in Table S2, the Ni particle size in Ni/h BaTiO2.00N0.34 was larger than that in the other catalysts. These results suggest that the variation in the ammonia decomposition activity is not due to structural factors such as the size of the supported Ni particles or the surface area of the support.

a Ni K-edge XANES spectra of various Ni-loaded catalysts after the NH3 decomposition reaction. b FTs of k3-weighted EXAFS oscillations for various loaded Ni-loaded catalysts after the NH3 decomposition reaction.

The electronic state of the Ni particle surfaces was further investigated via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements. As shown in Fig. 3, the Ni 2p3/2 peak for Ni/h-BaTiO3-x, Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34, and Ni/BaTaO2N appears at a similar position to that of metallic Ni (852.7 ± 0.4 eV)19. Only Ni/Ba5Ta4O15 showed a Ni peak below 852 eV, which indicates that negatively charged Ni formed on this catalyst. The Ni 3p spectra for Ni/LaTiO2N and Ni/La2Ti2O7 are shown in Fig. 3b, and the La 3d3/2 peak overlaps with the Ni 2p peak20,21. The Ni 3p peak position is almost the same as the Ni metal peak position (67 ± 0.2 eV). If electron donation from the support to Ni is a dominant factor for ammonia decomposition activity, then Ni/Ba5Ta4O15 should exhibit the best catalytic performance. However, Ni/Ba5Ta4O15 had a much lower activity than the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts. These results indicate that the high ammonia decomposition activity of the oxynitride-based catalyst is not attributed to an electron-donating effect.

a XPS Ni 2p3/2 spectra of Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34, Ni/h-BaTiO3-x, Ni/BaTaO2N, and Ni/Ba5Ta4O15 after the NH3 decomposition reaction. b XPS Ni 3p3/2 spectra of Ni/LaTiO2N and Ni/La2Ti2O7 after the NH3 decomposition reaction.

The decomposition of 15NH3 was conducted to clarify the contribution of the oxynitride support to the reaction mechanism. Both 30N2 and 29N2 gases were produced from the Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 catalyst, whereas 29N2 was not produced over Ni/h-BaTiO3-x (Fig. 4). This suggests that the lattice N3– in the oxynitride support is involved in the reaction. Figure 4 summarizes the initial 30N2 and 29N2 production during the decomposition of 15NH3 over various oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts. Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 resulted in the highest 29N2 production, although h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 had the lowest surface area and lowest nitrogen content among the tested oxynitrides. In addition, 29N2 production from Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 was initiated at ~350 °C (Fig. S6), which is consistent with the onset temperature for ammonia decomposition over Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 (Fig. 1a). The catalytic performance of the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts is thus governed by the reactivity of the lattice nitride anions on the support surface rather than the structural and electronic properties of the Ni particles.

29N2 and 30N2 production during 30 min of 15NH3 decomposition over various Ni-loaded samples at 450 °C.

Figure 5a shows the N2 temperature programmed desorption (N2-TPD) profiles for various oxynitride catalysts. N2 desorption from lattice nitrogen started at a lower temperature for Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 than for the other oxynitride-based catalysts. Figure 5b shows that the N2 desorption temperature significantly decreased after Ni loading of the h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 support, which indicated that the supported Ni particles facilitated the formation of nitrogen vacancy sites at the Ni-support interface. The N2 desorption temperatures for LaTiO2N and BaTaO2N also decreased after Ni loading (Fig. S7). This tendency is very similar to the results of the ammonia decomposition tests. As shown in Fig. 1 and S1, the oxynitrides without Ni loading exhibited much lower activity than did the Ni-loaded oxynitrides. These results imply that N2 desorption from the oxynitride support is a kinetically significant step that is facilitated by the supported Ni particles.

a N2-TPD profiles of various oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts. b N2-TPD profiles of h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 with and without Ni.

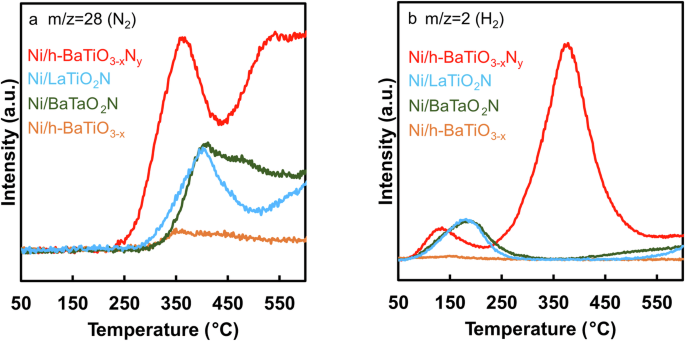

Ammonia-temperature programmed surface reaction (NH3-TPSR) measurements were conducted to explore the reactivity of the nitrogen vacancy sites on each catalyst. Prior to the measurement, each catalyst was heated under Ar flow at 600 °C to form nitrogen vacancy sites, after which NH3 was adsorbed at 50 °C. N2 and H2 were desorbed from the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts as the temperature increased (Fig. 6), which indicates that the adsorbed NH3 molecules decomposed on the catalyst surface at elevated temperatures. Ni/h-BaTiO3 showed very weak desorption peaks because the Ni surface and oxide support have very weak interactions with NH3 molecules. On the other hand, the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts exhibited strong N2 and H2 desorption peaks. Given the difference in the Ni particle size (Table S2), the large difference in the desorption peaks infers a difference in the number of nitrogen vacancy sites on the oxynitride supports, i.e., NH3 molecules are preferentially adsorbed at nitrogen vacancy sites on the oxynitride support. As confirmed by N2-TPD measurements (Fig. 5), many more nitrogen vacancy sites are formed on Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 than on the other catalysts after heat treatment in Ar at 600 °C. Consequently, Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 showed the most intense desorption peaks. N2 and H2 desorption was initiated at lower temperatures for Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 than for the other catalysts, which implies that NH3 molecules are effectively activated at nitrogen vacancy sites on Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 at lower reaction temperatures. Overall, these results strongly suggest that the nitrogen vacancy sites function as adsorption and active sites for ammonia molecules.

a N2 (m/z = 28) and (b) H2 (m/z = 2) desorption during NH3-TPSR over various Ni-supported catalysts.

Computational calculations

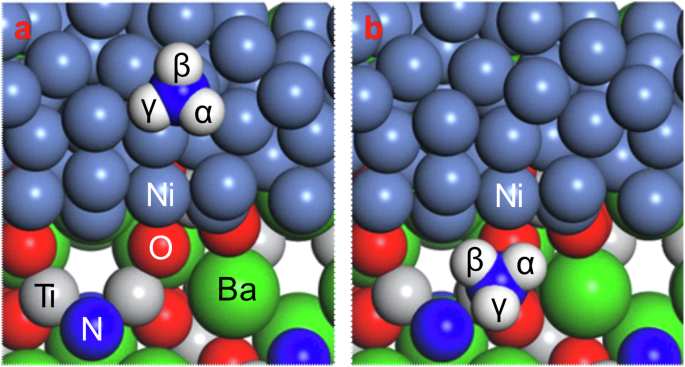

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to simulate NH3 adsorption on the catalyst surface. Prior to NH3 adsorption on the catalyst surface, the nitrogen vacancy formation energy (Ef(VN)) on the oxynitride-based catalysts was calculated. Ef(VN) for h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 could not be calculated because h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 originally has many intrinsic anion vacancy sites due to the 2N3– substitution of 3O2–, which leaves an oxygen vacancy and becomes unstable in the simulation when further VN sites are created. As summarized in Table S3, Ef(VN) decreases from 2.98 to 2.68 eV for BaTaO2N and from 2.23 to 1.98 eV for LaTiO2N after Ni loading. This result is consistent with the decrease in the nitrogen desorption temperature after Ni loading (Fig. S8). Therefore, it was experimentally and theoretically demonstrated that the supported Ni particles enhance the formation of nitrogen vacancy sites on the oxynitride surface. Next, the adsorption energy for NH3 (Ead(NH3)) on a catalyst surface with VN sites was calculated, and the optimum adsorption configuration is shown in Fig. 7 for Ni/h-BaTiO3-xNy and in Fig. S8 for Ni/BaTaO2N and Ni/LaTiO2N. For the Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 catalyst, h-BaTiO2N1/3ϒ2/3 was used as the model structure for the calculation. Ead(NH3) for the Ni surface was estimated to be –1.34 eV. On the other hand, NH3 molecules are adsorbed at Ti cation sites on the support surface adjacent to VN sites, with an Ead(NH3) of –1.41 eV (Table 1). Similarly, the NH3 molecules strongly interact with the support surface rather than the Ni surface on the Ni/LaTiO2N and Ni/BaTaO2N catalysts (Table S3). These results suggest that the ammonia decomposition reaction over the Ni-loaded oxynitride mainly occurs at VN sites near the interface between the supported Ni and the support.

Adsorption models for ammonia molecules on various oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts. Ammonia adsorption on (a) the Ni surface and (b) the support surface of Ni/h-BaTiO3-xNy.

The calculated lengths of the N‒H bonds of ammonia adsorbed on the catalyst surfaces are summarized in Table 2 for Ni/h-BaTiO3-xNy and in Table S4 for Ni/BaTaO2N and Ni/LaTiO2N. The N‒H bonds are more elongated on the surface of the oxynitride support with VN than on the Ni surface, which indicates that N‒H bond cleavage is facilitated on the support surface. A similar phenomenon is observed for the Ni/CaNH catalyst, i.e., ammonia molecules are dehydrogenated at anion vacancy sites on the CaNH surface rather than on the Ni surface, and N‒H bond cleavage occurs even at 50 °C6. Furthermore, the NH3-TPSR results in Fig. 6 show that the desorption temperature for N2 is higher than that for H2, which suggests that the rate-determining step for ammonia decomposition on the oxynitride-supported Ni catalyst is N2 desorption from the oxynitride support.

Conclusion

Compared with oxide-supported Ni catalysts, perovskite oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts exhibited much higher activity for ammonia decomposition. Among the tested catalysts, Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 showed the highest activity. The difference in activity is not due to differences in the support surface area, Ni particle size, or electronic state of Ni but rather to the ease of nitrogen vacancy formation on the oxynitride support. N2-TPD revealed that the supported Ni particles promoted nitrogen desorption from the oxynitride support and that Ni/h-BaTiO2.00N0.34 had the lowest nitrogen desorption temperature. NH3-TPSR and DFT calculations indicated that NH3 molecules are activated at nitrogen vacancy sites rather than at the Ni surface. N–H bond cleavage is facilitated at nitrogen vacancy sites on the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts, and N2 desorption from the oxynitride support is the rate-limiting step. These results provide new insights for the design of highly active and stable ammonia decomposition catalysts.

Materials and methods

Synthesis of BaTiO2.00N0.34 and h-BaTiO3-x

BaTiO2.00N0.34 was synthesized via a solid-phase reaction according to a previously reported procedure10,22. h-BaTiO3-xHx was synthesized via the solid-state reaction of BaH2 and TiO2. BaH2 was prepared by hydrogenation of Ba metal pieces (99.9%, Aldrich) under H2 gas flow (20 mL min–1) at 450 °C for 20 h. TiO2 nanoparticles (99.5%, Aldrich) were dehydrated at 500 °C for 6 h. BaH2 and TiO2 were then mixed in an Ar-filled glovebox using an agate mortar for 30 min. The mixture was placed in a quartz tube and heated under a H2 flow (10 mL min−1) at 800 °C for 20 h. The resultant powder was collected in an Ar-filled glovebox and washed with water several times to remove the small amount of impurity phase present, followed by drying overnight at 70 °C. BaTiO2.00N0.34 was prepared by heating h-BaTiO3−xHy at 600 °C for 12 h in a stream of pure N2 gas (10 mL min−1). h-BaTiO3−x was also prepared by heating h-BaTiO3−xHx at 800 °C for 12 h in an air atmosphere.

Synthesis of LaTiO2N and La2Ti2O7

Powders of LaTiO2N were obtained by nitridation of oxide precursors prepared via a polymerizable complex method. For oxide precursor synthesis, Ti(C4H9O)4 (Kanto Chemical, 97.0%), La(NO3)3·6H2O (Wako Pure Chemical, 99.9%), and citric acid (Wako Pure Chemical, 98%) were added to CH3OH (Kanto Chemical, 99.8%). After chelation, propylene glycol (Kanto Chemical, 99.0%) was added, and the mixture was gelatinized. The organic materials were carbonized at 550 °C to obtain the oxide precursors. Nitridation of 1.0 g of oxide precursors was performed under an NH3 stream (100 mL min−1) at 950 °C for 15 h in a tubular furnace. La2Ti2O7 was obtained by heat treatment of the oxide precursor at 950 °C for 15 h under an air atmosphere23.

Synthesis of BaTaO2N and Ba5Ta4O15

Powders of BaTaO2N were obtained by nitridation of oxide precursors prepared via a polymerizable complex method. For oxide precursor synthesis, Ta(C2H5O)5 (Kojundo, 99.999%), BaCO3 (Kanto Chemical, 99.9%), citric acid (Wako Pure Chemical, 98%), and propylene glycol (Kanto Chemical, 99.0%) were added to CH3OH (Kanto Chemical, 99.8%). After chelation and gelatinization, the organic materials were carbonized at 550 °C to obtain the oxide precursors. Nitridation of 1.0 g of oxide precursors was performed under an NH3 stream (100 mL min−1) at 950 °C for 15 h in a tubular furnace. Ba5Ta4O15 was obtained by heat treatment of the oxide precursor at 950 °C for 15 h under an air atmosphere23.

Ni loading method

Nickel-supported catalysts were prepared by H2 reduction of a mixture of support materials with Ni(η5-C5H5)2 (Tokyo Chemical Industry, 98.0%) at 250 °C for 1.5 h.

Characterization

X-ray diffraction analysis was conducted via a diffractometer (D8 ADVANCE, Bruker) with monochromatic Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm) at 45 kV and 360 mA. The air-sensitive samples were placed in airtight X-ray transmitting capsules in an Ar-filled glovebox and measured in air. The BET specific surface area of the catalysts was estimated from N2 adsorption isotherms measured at 77 K via an adsorption instrument (BELSORP-mini, MicrotracBEL). N2-TPD and NH3-TPSR measurements were conducted via a catalyst analyzer (BELCAT A instrument, BELCAT 2 instrument, BELMass, MicrotracBEL) under an Ar flow (10 mL min–1) in the temperature range of 25–1000 °C. XAFS spectra were analyzed via ATHENA and ARTEMIS software24 and the FEFF6 code25. The Ni particle size was calculated based on the coordination number calculated from the peak fitting results for Ni‒Ni bonds18. Ni has an fcc structure at room temperature and the nearest neighbor coordination number is 12. The Ni‒Ni bond coordination number for each catalyst was calculated using a value of 12, which is the coordination number for the Ni foil used as a reference in the measurements. XPS spectra (Kratos Ultra 2, Shimadzu) of Ni 2p and 3p were measured using Al Kα radiation at <10–6 Pa. The La 3d3/2 peaks for Ni/LaTiO2N and Ni/La2Ti2O7 were compared with the Ni 3p peak because the peak position is close to that of Ni 2p. The binding energies for all the spectra were calibrated with respect to the C 1s peak of the sample. All samples were sealed in transfer vessels in an Ar-filled glovebox to prevent oxidation by air and then introduced into the chamber.

Ammonia decomposition reactions

NH3 decomposition was performed in a fixed-bed plug-flow silica glass reactor at ambient pressure. Prior to the ammonia decomposition activity tests, the oxide-supported Ni catalysts and the oxynitride-supported Ni catalysts were heated under a N2/H2 mixed gas flow (N2/H2 = 1:3, 20 mL min–1) at 500 °C for 2 h for catalyst pretreatment. The catalytic activity and stability tests were performed using 0.1 g of catalyst at 360–660 °C under pure NH3 gas flow (25 mL min–1), which corresponds to a weight hourly space velocity (WHSV) of 15,000 mLNH3 gcat.–1 h–1. Effluent gases were analyzed with an online gas chromatograph (GC-14A, thermal conductivity detector (TCD), Porapak OS column, Shimadzu; He carrier gas).

15NH3 gas decomposition tests were performed at 450 °C for 30 min over Ni-loaded oxynitrides and h-BaTiO3−x (75 mg of catalyst) in a U-shaped silica glass reactor connected to a closed gas circulation system. 15NH3 (98% as 15NH3, 3.5 mmol) gas was introduced into the glass system, and the product gases were monitored with a mass spectrometer (M-101QATDM, Canon Anelva Corp).

Computational methods

DFT calculations were performed using the generalized periodic boundary conditions and gradient approximation with the Perdew–Vurke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional26 implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP)27,28. The core electrons were handled using the projector augmented wave method6, and valence electrons were represented with wave functions based on plane waves. The DFT calculations of the oxynitrides were implemented as follows: h-BaTiO2.00N0.34(110) contained 260 atoms with the bottom four layers of the 11 atomic layers fixed, BaTaO2N(001) contained 368 atoms with the bottom four layers of the 9 atomic layers fixed, and LaTiO2N(010) contained 306 atoms with the bottom four layers of the 10 atomic layers fixed. Each surface was the most stable among the low-index stoichiometric surfaces calculated via DFT. No spatial symmetry was imposed in the calculations. These surfaces were modeled using the supercell approach with sufficient vacuum regions of more than 20 Å to avoid artificial interactions between slabs that are periodically repeated along the axis normal to the surfaces. The z-axis was defined as the direction perpendicular to the surface plane. The cutoff energy of the plane wave basis set was 400 eV. The Monkhorst–Pack k-point grid for Brillouin zone sampling was 2 × 2 × 1 for each model, where the z-axis was defined as the direction perpendicular to the surface plane. The convergence criteria for energy and force were 1.0 × 10–5 eV and 1.0 × 10–2 eV Å–1, respectively, for all the models. For further correction, the DFT-D3 method of Grimme et al. with a zero-damping function was used29. Ni60-loaded h-BaTiO2.00N0.34(110), Ni70-loaded BaTaO2N(001) and Ni70-loaded LaTiO2N(010) were used for ammonia adsorption. The number of Ni atoms used was sufficient to fill one side of the structure. Ni is placed in four atomic layers on the catalyst surface and is fully relaxed. Visualization of the crystal structures was performed using the VESTA package30. The formation energy for N3– vacancies on the BaTaO2N surface, Ni70/BaTaO2N interface, LaTiO2N surface, and Ni70/LaTiO2N interface was defined as

where E(A) represents the total energy of system A, and Sd and Sp represent oxynitrides with and without surface VN, respectively.

The adsorption energy for the NH3 [Ead(NH3)] species on the surfaces was defined as

where Etot(NH3/surface) is the total energy for the optimized NH3 molecule adsorption configuration and Etot(NH3) is the total energy for NH3.

Responses