Efficacy of identifying Treatment-Resistant and non-Treatment-Resistant Schizophrenia using niacin skin flushing response combined with clinical feature

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a severe mental disorder with hallucinations, delusions, and behavioral disturbances as core symptoms. Up to 2019, the global prevalence of schizophrenia is approximately 23.6 million1. Currently, medication is the mainstay of treatment for schizophrenia, but about one-third of patients do not respond well to antipsychotic medication and develop treatment-resistant schizophrenia (TRS)2, which severely affects individuals’ physical health and social function3. At the same time, patients with TRS also increase the economic burden on society. A meta-analysis suggested that the cost of TRS is 3–11 times higher than that of patients with schizophrenia in remission in the United States4. Therefore, early identification of patients with TRS and timely adjustment of treatment strategies and management measures are crucial for patients’ physical health, social function and stability, and reduction of socioeconomic burden.

The search for predictors and biological markers associated with TRS is necessary for the early identification of patients with TRS. Previous studies have found that TRS is characterized by early age of onset5,6,7, long duration of disease8, multiple relapses9,10, and poor adherence to antipsychotic medication8 compared to NTRS. The above clinical indicators are important in our understanding of the factors influencing TRS. In addition, objective and effective biomarkers are an important basis for the differential diagnosis of this disease, and the combination of clinical features with biomarkers may be able to play a better role in the early identification of TRS.

In recent years, studies of the niacin skin flushing response (NSFR) in schizophrenia have suggested its potential as an objective biomarker for the differential diagnosis of the disease. The mechanism by which the NSFR occurs involves the phospholipase A2 (PLA2)–arachidonic acid (AA)–cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) cascade pathway. Niacin binds to G protein-coupled receptors on epidermal Langerhans cells and stimulates PLA2 to release AA from membrane phospholipids11. Free AA is subsequently metabolized by COX2 to prostaglandin D2 and prostaglandin E212, which subsequently promotes capillary dilation and skin flushing13. Previous studies have generally found reduced NSFR in patients with schizophrenia, suggesting its potential as a companion diagnostic biomarker14,15,16,17. However, in the differential diagnosis of schizophrenia with other disorders and healthy controls using the NSFR, the sensitivity is between 30% and 60%17,18,19, suggesting that only about half of the patients with schizophrenia could be screened by the NSFR. Factors contributing to this result may be related to the existence of different subgroups of schizophrenia, such as TRS and NTRS, but no study has yet demonstrated that TRS and NTRS differ in the NSFR and assessed the efficacy of identifying TRS using NSFR.

Therefore, the first aim of this study was to assess differences in NSFR between patients with TRS and NTRS. The second aim was to assess the potential efficacy of the NSFR combined with clinical features in the adjunctive diagnosis of TRS.

Methods

Participants

This study was conducted between October 2021 and December 2021 in Hunan Forensic Hospital of China. In this study, we recruited 269 patients with schizophrenia (99 TRS and 170 NTRS). Criteria for TRS: (1) met the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia; (2) after treatment with 2 antipsychotic drugs in full dosage or Clozapine monotherapy in full dosage (400–600 mg/d chlorpromazine equivalent dose), full course (≥6 weeks), and with good adherence to the medication, the symptoms do not improve significantly and still have moderate or severe symptoms (PANSS score >60), and the duration ≥12 weeks. Criteria for NTSR: (1) met ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia; (2) previous antipsychotic medication has been effective, with significant improvement in symptoms for more than 6 months; (3) the psychiatric symptom scores are mild or better. Exclusion criteria: (1) patients with schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, intellectual disabilities, epilepsy-induced psychosis, etc.; (2) history of organic brain diseases or craniocerebral injuries; (3) other serious physical illnesses; (4) refusal to participate this study. All participants’ information was kept strictly confidential and used only for this study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University and supported by the Hunan Provincial Institute of Compulsory Medical Treatment.

Measurements

A self-designed questionnaire was used to collect socio-demographic data, including age, sex, education level, history of smoking, history of alcohol use, family history of mental illness, age of first onset and course of disease, etc.

The severity of clinical symptoms in patients with schizophrenia was assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS). The PANSS consists of 7 positive symptom entries, 7 negative symptom entries, and 16 general psychopathology entries. Each entry is rated on a scale of 1–7, with a total score ranging from 30 to 210, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity20.

Subjects’ cognitive function was assessed using the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS), which consists of five cognitive dimensions: immediate memory, visual breadth, verbal function, attention, and delayed memory. Higher score on each dimension and the total score indicate better cognitive function21.

The Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaires (ITAQ) were used to assess the subjects’ knowledge of the disease and their attitude toward treatment. It consists of 11 items, each of which is categorized into 3 levels (score 0 = no insight, score 1 = partial insight, score 2 = good insight). The total score ranges from 0 to 22, with higher total scores indicating good insight22.

Niacin skin test

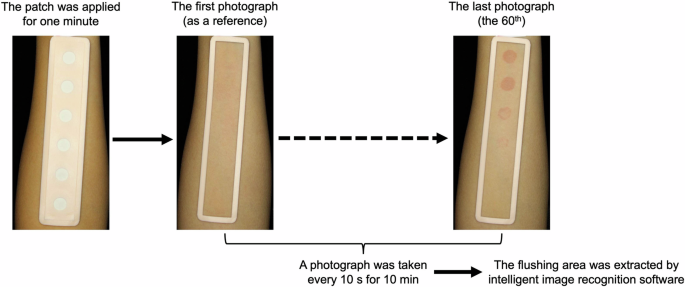

The operation of the niacin skin test was consistent with the previous study23. Niacin skin flushing response was tested using BrainAid Skin Niacin Response Test Instrument TY-AraSnap-H100 (Shanghai Tianyin Biological Technology Ltd., Shanghai, China). This tester consists of a standard patch, an automated imager, and intelligent image recognition software24. Equal volumes of aqueous methyl nicotinate (AMN, C7H7NO2, 99%, Sigma-Aldrich) of six concentrations (60, 20, 6.67, 2.22, 0.74, and 0.25 mM) were added into six separate holes of the patch, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1, the patch was contacted to the participant’s forearm for 1 min and then removed. Afterward, photographs of the subject’s forearm were taken from a fixed vertical perspective at 10-s intervals throughout the 10-minute period, for a total of 60 photographs per person. The raw quantification of each flushing spot was assessed using intelligent image recognition software. The first photograph was used as a reference, so there are a total of 354 primary flushing areas [6 AMN concentration × 59 photographs]. The sum of these 354 primary flushing areas was defined as the NSFR total area. EC50 for 60 mM AMN was calculated using nonlinear fitting to determine the duration required to produce a half maximum flushing area. A time-mean niacin flushing area plot was used to reflect the relationship between the niacin flushing area and time in subjects.

Simple flow chart for niacin skin testing.

Statistical analysis

Data was statistically analyzed using SPSS 26.0 software. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical variables were expressed as numerical values. Differences in continuous variables were analyzed using independent samples T-test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test. The relationship between the two variables was analyzed using Spearman correlation analysis. The role of age at the first onset, course of the disease, RBANS total score, ITAQ total, and NSFR in identifying TRS and NTRS was assessed using the ROC curve. P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics and clinical features

A total of 269 patients with schizophrenia (99 TRS, 170 NTRS) were included in this study. In the demographic characteristics, BMI (t = −2.184, p = 0.030) and history of smoking (χ2 = 6.171, p = 0.013) were statistically different between TRS and NTRS with NTRS having a higher BMI on average and a greater number of patients with a history of smoking. There was no statistical difference in sex, age, education, and history of alcohol use (p > 0.05). In the clinical features, age of first onset (t = −2.631, p = 0.009), course of disease (t = 2.331, p = 0.020), PANSS total score (t = 22.075, p < 0.001), RBANS total score (t = −2.421, p = 0.016) and ITAQ score (t = −12.920, p < 0.001) were significantly different between patients with TRS and NTRS. Patients with TRS were more likely to have a younger age of first onset, longer course of disease, higher PANSS scores, and lower scores on the RBANS and ITAQ. Family history of mental illness (χ2 = 0.950, p = 0.330) was not significantly different between the two groups. Specific details are shown in Table 1.

Differences in NSFR between patients with TRS and NTRS

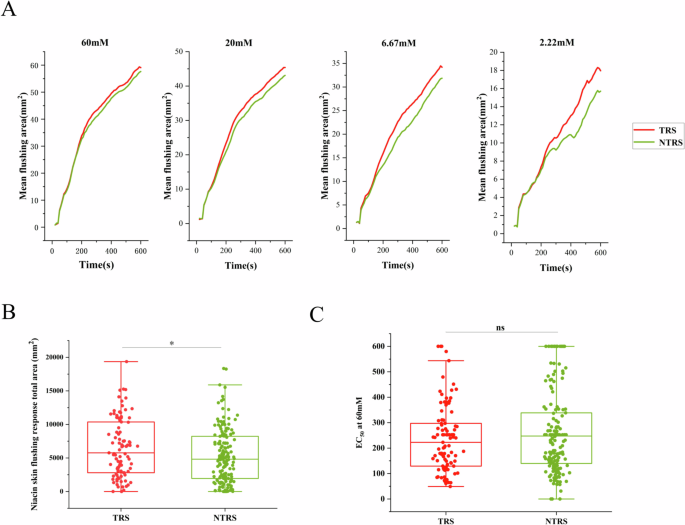

In this study, we analyzed the trend of the mean flushing area over time in the patients with TRS and NTRS. At the 60, 20, 6.67, and 2.22 mM concentrations, the mean flushing area was higher in patients with TRS than in patients with NTRS, as shown in Fig. 2A. However, this result was not a statistical difference. At the 0.74 and 0.25 mM concentrations, the mean flushing area was nearly zero, so the trend of the mean flushing area over time in the two concentrations was not evaluated.

A The time-flushing curves upon aqueous methyl nicotinate (AMN) stimulation of 4 higher concentrations. Flushing areas of the patients with TRS and NTRS are shown with mean. B The niacin skin flushing response total area in patients with TRS and NTRS. C The EC50 at 60 mM aqueous methyl nicotinate (AMN) of the patients with TRS and NTRS. TRS treatment-resistant schizophrenia, NTRS non-treatment-resistant schizophrenia. *p < 0.05; n.s. no significance.

Subsequently, we examined the NSFR total area in the patients with TRS and NTRS. It was found that the NSFR total area was higher in the patients with TRS than in patients with NTRS, and the difference was statistically significant (Fig. 2B). Next, EC50 was calculated based on the time flushing curve at 60 mM AMN and used to characterize the rate of NSFR. The EC50 was found to be lower in patients with TRS than in patients with NTRS, suggesting that patients with TRS only need a shorter period of time to reach half of the maximum niacin response area. However, this result was not a statistical difference, as shown in Fig. 2C.

Correlation between the NSFR total area and clinical features

In this study, we investigated the relationship between NSFR and clinical features. It found that PANSS score was negatively correlated with the age of first onset (r = −0.133, p = 0.029), RBANS total score (r = −0.184, p = 0.003), and ITAQ score (r = −0.728, p < 0.001), and positively correlated with course of disease (r = 0.121, p = 0.047). Course of the disease was negatively correlated with the age of first onset (r = −0.378, p < 0.001) and positively correlated with the NSFR total area (r = 0.132, p = 0.030). No significant correlation was found between NSFR and age of first onset, PANSS score, RBANS total score, and ITAQ score (p > 0.05). Specific details are shown in Table 2.

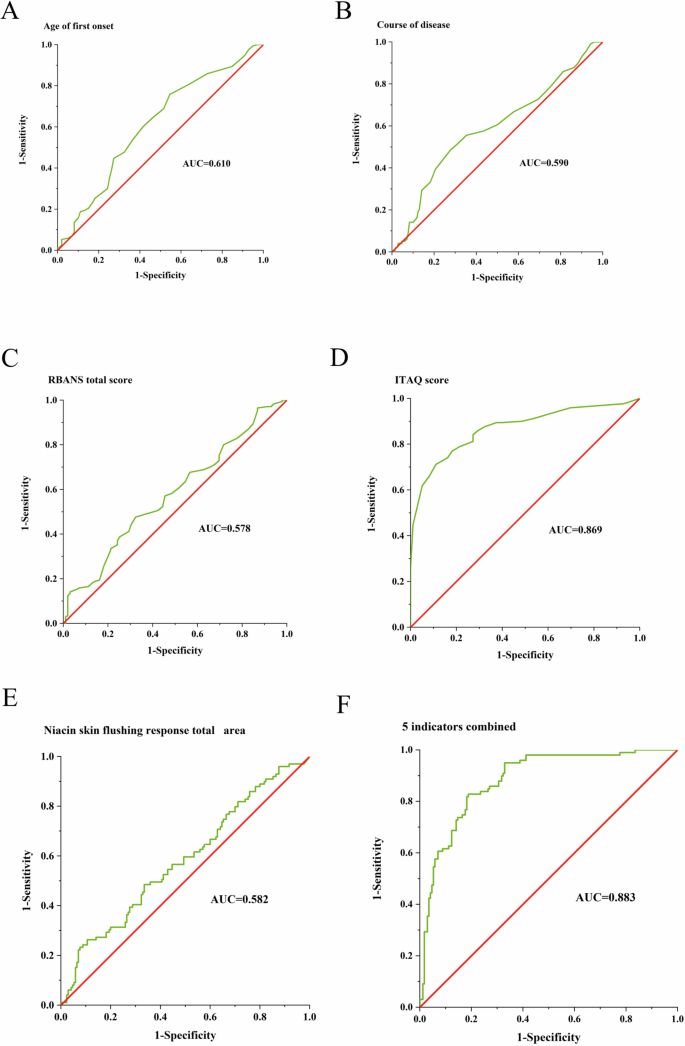

Efficacy of combined NSFR and clinical features to identify TRS and NTRS

In order to be able to recognize patients with TRS and NTRS, we constructed a diagnostic model based on the NSFR and clinical features. The NSFR had poor diagnostic efficacy with an AUC value of 0.582. The diagnostic efficacy of age of first onset, course of disease, and RBANS total score for the identification of TRS was poor, with AUC values ranging from 0.578 to 0.610. ITAQ score had a better diagnostic efficacy for patients with TRS and NTRS with an AUC value of 0.869. The combined diagnostic efficacy of age of first onset, course of disease, RBANS total score, ITAQ score, and NSFR was 0.883, which is a better diagnostic efficacy. The relevant specific data is shown in Fig. 3.

A–F ROC curve for identifying TRS by the age of first onset, course of the disease, RBANS total score, ITAQ score, niacin skin flushing response total area, and above 5 indicators combined, respectively. RBANS repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status. ITAQ insight and treatment attitudes questionnaires. AUC area under curve.

Discussion

This study found that the NSFR was more pronounced in patients with TRS than in patients with NTRS. Previous studies have found that the NSFR becomes blunted in a proportion of patients with schizophrenia compared to healthy controls and that there is no difference in the NSFR in a proportion of patients with schizophrenia14,15,16,17. This suggested that a subtype of blunted NSFR may exist in patients with schizophrenia, such as TRS. However, the results of the present study seem to be inconsistent with the traditional understanding. Our study found that the NSFR was more sensitive in patients with TRS compared to NTRS. Current studies have focused on exploring the mechanisms of niacin abnormalities in schizophrenia, and there is no better explanation for niacin abnormalities in TRS. Therefore, the mechanism of NSFR abnormality in patients with TRS and NTRS will be an important task in our next phase.

Next, we will discuss some of the possible confounding factors about the niacin test. Firstly, Clinical studies have found that sex and age have an effect on the NSFR. Female patients are more sensitive to NSFR than male patients, and younger patients are more sensitive to NSFR than older patients25,26. There was no statistically significant difference in the sex ratio and age between the two groups in this study, avoiding the influence of sex and age on the NSFR. Secondly, previous studies have not found an effect of nicotine on NSFR27. Similarly, no significant effect of nicotine on niacin sensitivity was found in animal studies with either acute or chronic administration of nicotine28. Therefore, although there was a difference in the proportion of smoking history between the two groups in this study, the effect of smoking on NSFR could be disregarded based on the results of previous studies. Thirdly, all patients were taking antipsychotic medication at the time of doing NSFR, raising the question of whether antipsychotic medication affects the NSFR. One study found a blunted NSFR in patients taking antipsychotic medication compared with those taking no medication29. Therefore, the effect of long-term antipsychotic medication on niacin sensitivity cannot be ruled out in this study. Next, it is necessary to enroll and follow up patients with first-episode schizophrenia in the outpatient clinic and evaluate the effect of different medications on the NSFR in patients with TRS and NTRS.

In addition, in the clinical features, we found an earlier age of first onset in patients with TRS compared to NTRS, which is the most consistent point among the clinical features of patients with TRS6,30,31,32. A meta-analysis has found that younger age of first onset is associated with a variety of poor outcomes in schizophrenia, such as more hospitalizations, more negative symptoms, more relapses, poorer social/occupational function, and poorer overall prognosis33. This study also found a negative correlation between the age of first onset and PANSS total score, indicating that the younger the first onset, the more severe the psychiatric symptoms. The younger first onset may suggest that it may be more influenced by genetic factor34,35, which may be one of the reasons why it becomes treatment-resistant. In addition, this study found that patients with TRS had a longer course of disease and more severe impairment of cognitive function and insight, which correlated with the severity of psychotic symptoms. Therefore, if a subject has an outcome with the above four indicators, then we should be highly alert to the possibility of developing TRS.

Currently, the NSFR has achieved good power in recognizing schizophrenia, mood disorders, or those without mental illness17,36. However, the role of NSFR in recognizing TRS has not been studied. This study is the first time to use NSFR in combination with clinical features to identify patients with TRS and NTRS. The results of this study suggested that a single NSFR has poor efficacy in recognizing TRS. Indeed, TRS is often not recognized in time in clinical settings. The findings of this study may provide a theoretical basis for the early identification of patients with TRS, which is expected to play a positive role in guiding the use of medication by clinicians. For example, clozapine is the only antipsychotic recommended for patients with TRS6, and it is more effective than other antipsychotics in relieving psychotic symptoms in patients with TRS37,38. However, the use of clozapine is often delayed in patients with TRS39. Multiple and high-dose antipsychotics were often used prior to the administration of clozapine with less benefit to the patient. Therefore, if this period of inadequate treatment could be shortened, it would have important implications for patients’ symptomatic outcomes. In addition, the results of this study could be used for early identification of TRS and will have a salutary effect on the management of patients with TRS. Families, communities, and governments will need to focus on this group of patients to understand the dynamics of their illnesses and do a better job of prevention, which will play a positive role in reducing the economic burden on families and society.

Limitations

Firstly, our study did not have a healthy control group, and the difference in niacin between patients and healthy controls was not able to be measured. Secondly, the patients in this study were on long-term antipsychotic medication, and the effect of antipsychotic medication on the NSFR could not be ruled out. the patients were hospitalized for a long period of time, and the results of the study may be less applicable to outpatients, which needs to be further validated in the clinic.

Conclusion

Among the clinical features, the ITAQ has an important role in recognizing treatment-resistant schizophrenia. The NSFR has a poor efficacy in recognizing treatment-resistant schizophrenia.

Responses