Efficient reinterpretation of rare disease cases using Exomiser

Introduction

High-throughput and lower-cost sequencing have enabled the integration of whole-exome and whole-genome sequencing (WES/WGS) in clinical practice and the advent of large sequencing projects for rare Mendelian diseases. However, a substantial fraction of rare disease patients (50–80%) remain currently undiagnosed following WES/WGS1. One explanation for this shortfall is that the causative variant is in a gene that has not yet been identified as associated with the patient’s condition at the time of analysis. Hundreds of new disease-gene associations are discovered every year, highlighting the need to reevaluate unsolved cases. To address this, a periodic reinterpretation of the genetic data for undiagnosed individuals has been proven to increase the diagnostic yield by 10–15%2 and it has the potential to bridge the gap between ever-changing scientific knowledge and clinical practice for patient benefit. However, even with the automation of some steps, reanalysis of these sequences is a laborious process, so efficient methods are required to more broadly apply reinterpretation for increasing diagnostic yield.

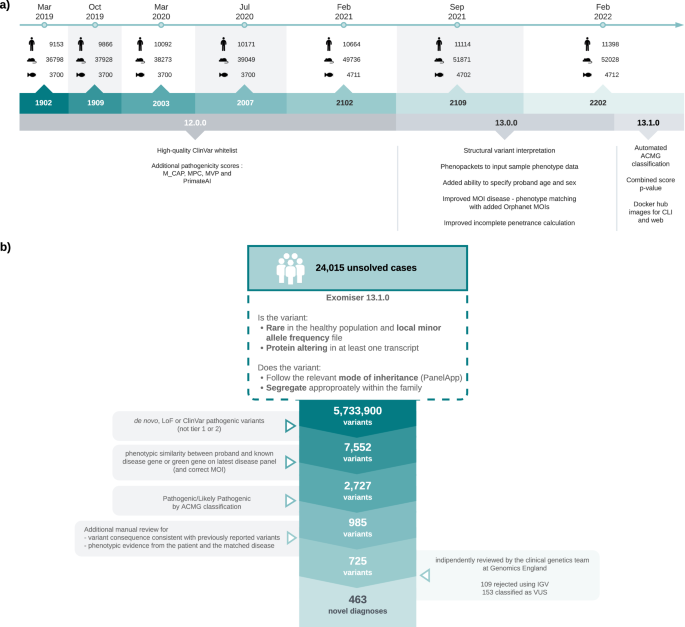

Exomiser is a phenotype-driven tool that leverages information on variant frequency, predicted pathogenicity and similarity between the patient’s phenotypes and annotations of human disease genes, model organisms or protein-protein associated neighbours to filter and prioritise likely causative variants. We regularly update the software with new features as well as incorporate the latest knowledge into the underlying reference databases e.g. newly discovered disease-gene associations (Fig. 1a). For almost a decade, the Exomiser software framework3 has been used in primary diagnostic pipelines in large-scale projects such as the Undiagnosed Disease Program3 and 100,000 Genomes Project (100kGP)1. In this study, we now demonstrate that it also offers a scalable and efficient solution for genetic reinterpretation.

a Timeline of Exomiser software and database releases. Details are shown for the Feb 2019 to Feb 2022 time period analysed in this study for new software features (below) and numbers (above) of human (disease), mouse and zebrafish annotated gene associations in the underlying database. b Summary of reinterpretation strategy applied to 24,015 unresolved cases. The figure demonstrates a stepwise reduction in the number of variants per filtering stage by employing a conservative candidate selection approach that led to the identification of 463 novel diagnoses. Figure generated using LucidChart.

Results

To assess the use of Exomiser for reinterpretation, incorporating the latest knowledge of diseases, genes and phenotypes, a large-scale reanalysis of 24,015 unsolved cases from the 100kGP was performed: selected on the basis of not having a known diagnostic finding after the 100kGP primary pipeline run 2016–2019. The 100kGP primary pipeline largely involved the identification and interpretation of rare, segregating, de novo, predicted loss-of-function (pLoF) or predicted pathogenic missense variants in curated panels of known genes related to the patient’s disease in PanelApp4. These 24,015 cases were analysed using Exomiser 13.1.0 and the Feb 2022 database release, with default settings on single proband and family-based variant call format (VCF) files. This generates rare (<0.1% autosomal/X-linked dominant or homozygous recessive, <2% autosomal/X-linked compound heterozygous recessive; using publicly available sequencing datasets including gnomAD), protein-coding (including canonical splice acceptor/donor and splice region), segregating and most predicted pathogenic (per each gene) candidate variants for each case.

A conservative candidate selection procedure was used to identify the 725 most likely diagnoses (Fig. 1b). First of all, the Exomiser combined scores were rescaled to new 0–1 scores using the softmax function: exp(10 * score)/sum(exp(10* score)) for the top-ranked scores (up to a maximum of 1000). Only those scoring above 0.1 were retained. These were further filtered for:

-

having a human phenotype score >0.6 or involving a gene classified green in the latest recruited disease panel (23/2/2022) in PanelApp4 with the correct mode of inheritance for the disease-gene association;

-

classified as either (i) de novo by the 100kGP, (ii) pLoF by Exomiser, or (iii) P/LP by ClinVar with non-conflicting evidence and multiple sources;

-

not classified as tier 1 or 2 and, hence, already interpreted and rejected by the GMCs in the previous pipeline;

-

classified P/LP by Exomiser’s automated ACMG classifier;

-

variant type (missense versus LoF) consistent with previously reported variants for the disease;

-

hallmark phenotypic features of the disease present in the patient.

Finally, the 725 candidates were independently reviewed by the Genomics England clinical genetics team to identify 463 (2% of the 24,015 cases) to return as newly discovered diagnoses, with 153 remaining as variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and 109 rejected as false variant calls after IGV review (Fig. 1b). The Genomics England team is composed of clinical scientists and geneticists and performed an equivalent variant classification to that which would be performed in a diagnostic laboratory and confirmed 463/616 (75%) of automatically classified, correctly called variants were indeed P/LP.

251/463 of these new diagnoses were based on ClinVar P/LP variants with consistent evidence from multiple submitters: 144 were identified in the original 100kGP pipeline but overlooked as they affected genes outside the panel at the time of analysis, whilst 107 were previously filtered out and retained here due to Exomiser whitelisting feature where such variants are always retained regardless of filtering settings. 98/463 new diagnoses were made based on de novo or LoF variants in genes that are present on the latest versions of the panels associated with the patient’s disease. For 84/99 of these, the gene was not on the panel when the primary 100kGP pipeline was run, suggesting new evidence has since emerged for the disease-gene association. For example, a de novo PPP3CA:p.Asn117Lys variant in an intellectual disability patient was the top-ranked Exomiser candidate based on the association to Houge-Janssens syndrome 3 described in 20195 and therefore not highlighted in the 100kGP primary pipeline run prior to that date. Finally, Exomiser highlighting of candidates in genes that are still not present on the disease panel associated with the patient was responsible for 114/463 of new diagnoses, e.g., a de novo MORC2:p.Gly36Arg variant in a mitochondrial disorders patient was the top ranked Exomiser candidate based on the association with a newly described neurodevelopmental disorder6. Overall 330 (72%) of the 463 diagnoses involved a variant that was identified in the primary 100KGP pipeline but in a gene that was not in the relevant panel(s) at the time. 205 (62%) of these disease-gene associations were already known and overlooked by the PanelApp strategy revealing the higher sensitivity of a less targeted approach, whilst the remainder represent new discoveries identified in the reinterpretation.

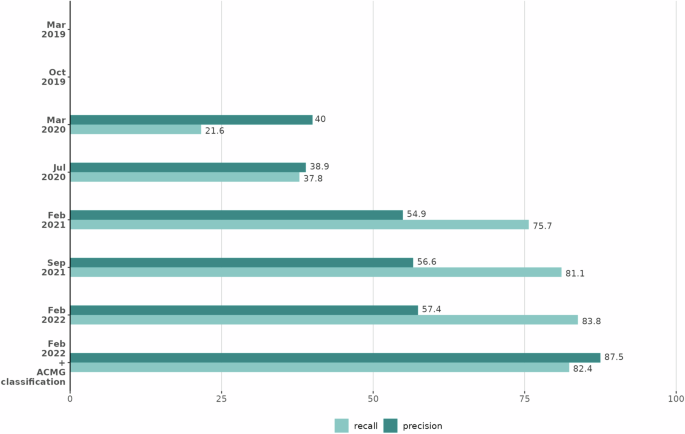

Extensive manual interpretation was required for these new diagnoses; consequently, future reanalysis would ideally only highlight candidates due to new disease gene discoveries or newly assigned P/LP variants. We therefore investigated the best strategy to achieve this with the Exomiser framework on 37 solved cases from the 100kGP primary pipeline based on all those identified with a diagnosis in a disease-gene association appearing in OMIM between February 2019 and February 2022. This date range was chosen as Exomiser database releases from this time period are backwards-compatible with Exomiser 13.1.0. Ideally, a much larger cohort of solved cases would have been used in this evaluation but we were also limited by most 100kGP cases having been analysed prior to 2019. Exomiser 13.1.0 was run on these cases using all seven versions of the database from Feb 2019 till Feb 2022. We investigated in detail the combination of Exomiser variant and human phenotype scores that optimised the detection of these new diagnoses whilst reducing the number of false positive candidates to investigate (Supplementary Table 1). The selection of these two scores was made to ensure independence between the two variables while enabling the capture of both likely pathogenic variants via the variant score and newly discovered disease-gene associations through the increments in the human phenotype score. Each variant called by Exomiser was classified as a true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP) or true negative (TN) by comparing the results obtained using the combination of Exomiser score tested and a trusted external observation (the diagnosed variants). Measures of recall and precision, as well as F and F2 scores, were derived using R/4.2.1. The F2 score, which is a weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall where recall is weighted higher than precision, is often utilised in diagnostic settings and was used for optimising the best combination of scores.

A combination of variant score >0.8 and an increase in human phenotype score of 0.2 between Exomiser runs was identified as the optimal way to detect candidates. Comparing Exomiser results based on Feb 2019 vs Feb 2022 analysis (Fig. 2), these thresholds highlight 54 new candidates in the 37 solved cases with 31 being the correct diagnosis, representing impressive recall (84%) and precision (57%). For the 6 cases not detected by these criteria, this was due to missense variants having a low predicted pathogenicity or patient Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) terms not similar enough to the new disease-HPO annotations to increase the score by 0.2. For the former, future incorporation as P/LP in ClinVar will ensure they get flagged due to Exomiser whitelisting. On the latter, presumably, additional phenotype data was available to the recruiting clinician to make them confident of the diagnosis. Finally, Exomiser’s automated ACMG/AMP classifier converted 92% of the diagnostic variants from VUS to P/LP and including this extra condition in the reinterpretation strategy further improves precision to 88% with only a small drop in recall to 82%. On the basis of this investigation, we recommend a combination of variant score > 0.8 and an increase in human phenotype score of 0.2 to easily identify candidates from Exomiser’s programmatic output (TSV, VCF or JSON). From the analysis of the families investigated here, this reduces the number of candidates to review per case from a median of 30 (range 11-214) to only one or two variants per case. The number and complexity of variants to review after Exomiser filtering obviously varies but based on typical interpretation times per variant, this will make it possible to reinterpret a case in minutes rather than more than an hour.

Precision (dark green bars) and recall (light green bars) are shown for each Exomiser database release when new candidates were selected for the 37 cases based on an increase in the human phenotype score of 0.2 and a variant score >0.8 and, for the final bars, when also restricting to those variants classified as pathogenic/likely pathogenic by Exomiser’s automated ACMG classifier. Each version of Exomiser (Y axis) shows increased precision and similar or better recall than previous versions. Figure generated using R/4.2.1.

Discussion

In this study, we have shown how Exomiser reanalysis can identify many new diagnoses, even when restricting to coding SNV/indels with a high probability of being pathogenic and affecting known disease genes linked to the patient’s disease or phenotypes. As reviewed above, previous studies have estimated a 10–15% increase in diagnostic yield so our study shows the lower limit of what can be achieved through reanalysis, and more extensive investigations of the non-coding, structural and novel disease-gene candidates highlighted by the Exomiser framework would likely increase the diagnostic uplift further. While the current analysis focused on SNV/indels within coding regions as well as canonical splice acceptor/donor sites and splice regions, there is potential for future studies to include a broader spectrum of genomic variation. Since v13.0.0, Exomiser has been able to handle and prioritise structural variants; therefore, this enhancement offers an opportunity to include SVs in future analyses, potentially furtherly improving the diagnostic yield. Furthermore, the use of Genomiser could help address the limitations associated with non-coding regions and regulatory regions that were excluded from the current analysis. Our analysis used the original VCFs generated for the 100kGP analysis pipeline but realignment and variant calling of the original samples could also identify new diagnoses. In addition, variants already classified as tier 1 or 2, and thus previously interpreted and rejected by the GMCs, were excluded from consideration. This filtering may have eliminated potential diagnoses in the reinterpretation where further variant-level evidence of pathogenicity now exists, e.g. newly classified as P/LP in ClinVar. The potential lags in Exomiser in incorporating new discoveries could also be reducing the reinterpretation yield. However, we suspect that the biggest factor is that the 100kGP recruited samples from a vast range of rare disease categories with highly varying chances of being explained by monogenic genetic causes and hence diagnostic yields1 and likely low reinterpretation yields for some categories as well.

We have demonstrated that simple strategies applied to Exomiser’s output can considerably reduce the number of candidates to be considered in each reanalysis, allowing users to build their own scalable and efficient reinterpretation pipelines or services. Our approach relies on teams at OMIM, Orphanet and Monarch to efficiently curate disease-gene and disease-phenotype associations from the ~200 new association publications each year7. These are incorporated into the disease databases and HPO annotations (HPOA) a few months after publication and Exomiser incorporates these associations in its next biyearly release. Moving to more regular Exomiser database releases, particularly when synchronised with the quarterly HPOA releases, will help to reduce any lag before associations can be detected by Exomiser and we have recently streamlined our build process to make this feasible from now on. However, although Exomiser can be run on a case in minutes and our reinterpretation strategy highlights only 1–2 new candidates to reinterpret on average, yearly reinterpretation is probably a reasonable compromise given disease-gene discovery rates and incorporation times into Exomiser. An alternative strategy is to use natural language processing of the published literature to incorporate this new knowledge in a shorter time-frame such as in the AMELIE approach8. However, the improved quality of the disease, gene and phenotype annotations from the efforts of the OMIM and HPO curation teams are then lost, potentially resulting in a lack of accuracy. We are also investigating a middle approach where we prioritise HPO annotation and Exomiser incorporation of new disease-gene associations that may appear in multiple GenCC9 contributing sources before OMIM and Orphanet. In conclusion, this study underlines the key role of reinterpretation methodologies, aiming to tackle the challenge of extensive manual interpretation by promoting an efficient reinterpretation strategy using Exomiser.

Methods

Analysis of 100kGP samples

Exomiser 13.1.0 was run with default settings on single proband and family-based VCF files for unsolved 100kGP cases. All patients included in this study consented to participate in the 100,000 Genomes Project – ethics approval by the Health Research Authority (NRES Committee East of England) REC: 14/EE/1112; IRAS: 166046 and we complied with all relevant ethical regulations including the Declaration of Helsinki. This generates rare (<0.1% autosomal/X-linked dominant or homozygous recessive, <2% autosomal/X-linked compound heterozygous recessive; using publicly available sequencing datasets including gnomAD), protein-coding (including canonical splice acceptor/donor and splice region), segregating and most predicted pathogenic (per each gene) candidate variants for each case. Exomiser output was processed to select the most likely diagnoses. First of all, the Exomiser combined scores were rescaled to new 0–1 scores using the softmax function: exp(10 * score)/sum(exp(10* score)) for the top ranked scores (up to a maximum of 1000). Only those scoring above 0.1 were retained. These were further filtered for:

-

having a human phenotype score >0.6 or involving a gene classified green in the latest recruited disease panel (23/2/2022) in PanelApp4 with the correct mode of inheritance for the disease-gene association;

-

classified as either (i) de novo by the 100kGP, (ii) pLoF by Exomiser, or (iii) P/LP by ClinVar with non-conflicting evidence and multiple sources;

-

not classified as tier 1 or 2 and, hence, already interpreted and rejected by the GMCs in the previous pipeline;

-

classified P/LP by Exomiser’s automated ACMG classifier;

-

variant type (missense versus LoF) consistent with previously reported variants for the disease;

-

hallmark phenotypic features of the disease present in the patient.

Reanalysis optimisation

We assessed and compared the performance of seven releases of the Exomiser database from February 2019 to February 2022 in detecting diagnoses among 37 100kGP patients that remained unsolved as of February 2019 but later received a diagnosis based on newly discovered disease-gene associations. We evaluated how Exomiser performed using different combinations of variant scores and increments in human phenotype score thresholds. The selection of these two scores was made to ensure independence between the two variables while enabling the capture of both likely pathogenic variants via the variant score and newly discovered disease-gene associations through the increments in human phenotype score. Each variant called by Exomiser was classified as a true positive (TP), false negative (FN), false positive (FP) or true negative (TN) by comparing the results obtained using the combination of Exomiser score tested and a trusted external observation (the diagnosed variants). Measures of recall and precision, as well as F and F2 scores, were derived using R/4.2.1. The F2 score, which is a weighted harmonic mean of precision and recall where recall is weighted higher than precision, is often utilised in diagnostic settings and was used for optimising the best combination of scores.

Responses