Electro-spun nanofibers-based triboelectric nanogenerators in wearable electronics: status and perspectives

Introduction: Mechanical energy utilization for greener wearable electronics

Dependence on non-renewable energy sources has caused significant economic and environmental issues1. Environmental protection, energy efficiency, and improved “access-for-all to energy” must be prioritized simultaneously, in order to achieve sustainable development in short term2. There are various ongoing efforts to harness diverse renewable energy sources like solar, wind, and other kinetic energies, fostering the development of portable and personalized energy needs; among these, particular attention has to be paid to those that are related to wearables3. Giving the fact that one quarter of the world’s energy consumption is due to tribology4, in principle, the conversion of friction-dependent mechanical energy to electrical energy could be one of ideal solutions to energy problem, especially involving waste materials, like plastics and polymers5,6. In this regard, the outcomes of recent exploration of triboelectric-based energy extraction from biocompatible nanomaterials that are used in wearable electronics, have led to important clues7,8,9,10. On the other hand, in the era of the Internet of Things (IoT) and artificial intelligence, a large amount of data have been accumulated, via mobile electronic devices and robots as mechanical energy-based self-powered systems3,11,12,13.

In 2012, a breakthrough in energy harvesting was accomplished with the development of triboelectric nanogenerators, TENGs14. As TENG is about conversion of otherwise-wasted mechanical energy into electrical energy, it holds immense promise as a clean and sustainable energy source, offering significant potential to address global energy challenges. The core principle underpinning TENG operation lies in the triboelectric effect. When dissimilar materials come into contact, separate, or experience friction, this effect induces charge separation, leading to the generation of electric current15. The inherent self-powering nature of TENG unlocks exciting new possibilities for the development of micro- and nano-scale systems. From low voltage fluctuation and sensing features of sensors to efficient energy harvesting-based automotive industry, all the nanogenerator technologies led by TENG cover a broad spectrum of potential applications16,17,18,19, particularly related to wearable technologies.

From materials point of view, compared to their bulk counterparts, nanomaterials like nanofibers possess unique size- and surface-dependent properties, including high specific surface area and distinctive physical and chemical characteristics20,21. For instance, nanofiber forms (such as membranes) offer superior performance compared to conventional thin films by means of enhancement of the piezoelectric effect22. Various kinds of electro-spun nanofibers23, that have been used in TENGs24, already demonstrated superior performance in wearable technologies. Therefore, at the intersection of wearable electronics and TENG, electro-spun nanofibers hold great promises, as depicted in Fig. 1a. These kinds of nanostructures are better endowed as materials for wearable devices with exceptional breathability, which is a crucial factor for user comfort24,25,26, as showcased in Fig. 1b. In this sense, electrospinning stands as a preferred growth technique of nanofibers (a stereotype of an electrospinning system is illustrated at the bottom left of Fig. 1a). Currently, by leveraging electro-spun membranes, TENGs can functionalize piezoelectric and dielectric properties of electroactive polymer and composite materials via structural optimization, intelligent design and integration with cooperating devices. For instance, composite electro-spun nanofibers made out of poly(vinylpyrrolidone) and amorphous TiO2 have been realized (Fig. 1c), which can provide enhanced TENG output. Especially, electro-spun nanofibers pertaining to energy harvesting (such as TENG), self-powered, and sensing devices have been fueling significant advancements in the realm of smart textiles.

a Schematic illustration of the interaction and use of electro-spun nanofibers-based nanogenerators in wearable electronics: a belt-drive for several important applications is defined. At the bottom left a typical electrospinning visual is given23. b A typical example of electro-spun nanofibers-based highly elastic and breathable triboelectric nanogenerator (TENG) consisting of PVDF, polyurethane, and carbon nanofibers. Reprinted with permission24. Copyright 2020, Wiley. c An SEM image of electro-spun composite polymer nanofiber is shown. Reprinted with permission23. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. d Main operational modes of TENG are shown: (i) contact-separation, (ii) lateral (or in-plane) sliding, (iii) single-electrode, and (iv) freestanding triboelectric layer mode. Gray (blue) color represents tribo-negative (tribo-positive) active layer, and light orange color is the electrode; cyan color clockwise arrow indicates the operation cycle. At the center of (d), an equivalent circuit for TENG is given. Reprinted with permission27. Copyright 2023, IOP Publishing.

Driven by the above-mentioned motives, an overview of electro-spun nanofibers as nanogenerator materials for the future of wearable electronics was found to be necessary. After introducing the fundamental principles of TENGs and a brief qualitative knowledge on electrospinning production method, the most noticeable progresses on the most commonly employed polymer nanofibers in TENG fabrication will be presented with discussions delving into current challenges. It is indispensable to mention applications of these TENGs in wearable self-powered sensors, human-machine interaction (HMI) technologies, smart home systems, and amplified energy harvesting. In the light of current status of the field, there are several conclusive results as well as open questions and ideas to be referred to. Among these, we will particularly pay tribute to the ones related to materials’ properties. For the future, we will underline the importance of hybrid nanofibers, which can aspire unprecedented, novel functionalities to be used in TENGs for wearable electronics.

Working principles of triboelectric nanogenerator

Mechanical energy harvesting devices, namely TENG, capitalize on the triboelectric effect and electrostatic induction to convert ubiquitous mechanical energy into electrical energy15. This technology takes advantage of the intrinsic physical and chemical properties of certain materials to acquire an electrical charge upon exertion of frictional forces at nanoscale and subsequent charge separation processes. In a TENG device, this principle is exploited by bringing two dissimilar materials with contrasting triboelectric properties. This process induces charge transfer, resulting in generation of potential difference and charge flow from contacting materials to electrodes. Notably, TENG can be categorized into four main operating modes: contact-separation, lateral sliding, single-electrode, and freestanding triboelectric layer27,28.

Contact-separation mode

The (vertical) contact-separation mode represents the most prevalent configuration for TENG. It features two vertically stacked dielectric materials, each equipped with electrodes on their opposing surfaces (Fig. 1a(i)). The continuous process of alternating contact and separation between these layers induces a potential difference, which is due to friction in the case of TENG. To achieve equilibrium, electrons flow through the external circuit, driven by this potential difference. This mode offers several advantages, including a straightforward design, high durability, and impressive power density. These attributes, coupled with the ease of modeling and analysis, make vertical contact-separation TENG highly attractive27,28,29,30. In particular, their practical applications extend to wearable devices, such as energy-harvesting shoe soles31. The natural simplicity and intuitive operation of this mode translate to broader applicability compared to other TENG configurations; for instance, it has been frequently used in ocean energy harvesting32,33. Due to its well-understood physical mechanism, straightforward manufacturing process, and ease of operation, the vertical contact-separation mode has become default mode for TENGs. It provides a robust platform for further exploration and advancements in the field.

Lateral sliding mode

The contact and in-plane (simply in-plane) or lateral sliding mode can be taken as an alternative configuration for TENG, characterized by planar layers engaged in sliding or rotational motions (Fig. 1d(ii)). This approach promotes enhanced charge generation and output power by eliminating the need for an air gap between the frictional surfaces31. However, a trade-off exists, as high-frequency friction can accelerate material wear, thereby diminishing device lifespan. In this configuration, sliding interfaces composed of friction materials like metals, semiconductors, or polymers induce directional electron flow to compensate for potential differences34,35. While in-plane sliding TENG exhibits lower durability compared to its vertical counterparts due to wear concerns, it can offer expanded energy collection capabilities. This advantage broadens the potential applications of nanogenerator technologies, such as wind-driven (including piezoelectric nanogenerator, PENG)36. Also, the advantages of in-plane sliding mode over contact-separation were demonstrated in random vibrational energy harvesting37.

Single-electrode mode

The single-electrode mode offers a simplified configuration of TENG, featuring a reference electrode grounded to the environment that interacts with a freely moving dielectric material (Fig. 1c(iii)). This design facilitates charge generation through periodic cycles of contact and separation, like in the case of ion injection in magnetic field-guided environment38. As the dielectric material comes into contact with the electrode, variations in the contact area and surface friction induce electron redistribution. This results in a potential difference arising between the electrode and ground, triggering electron flow to achieve equilibrium. Upon separation, electron flow ceases; however, the electrode retains a specific electron distribution due to electrostatic effects. Subsequent contact cycles reinitiate electron flow, generating a characteristic periodic current output. The inherent simplicity of this mode translates to advantages in manufacturability and user-friendliness, leading to practical applications in areas such as snowfall energy collectors39, strain, and angle measurement sensors40,41. While the single-electrode mode exhibits lower electron transfer efficiency, its streamlined design makes it a compelling choice for scenarios, where intricate multi-electrode configurations are impractical42,43.

Freestanding triboelectric layer mode

The nature of this mode contains similarities to the single-electrode mode, with an essential difference of generating electrical energy out of freely moving objects (Fig. 1d(iv)). Unlike space-confined features of modes (i) and (ii), this configuration offers several advantages and ranks as one of the principal working modes for TENG44,45. Also, its design aims to address limitations inherent to the single-electrode mode, such as output performance and charge transfer efficiency46,47,48. Freestanding nanogenerators operating in this mode can generate energy through contact-separation or sliding movements without constraints imposed by the triboelectric layer, thereby enhancing energy harvesting from all-directional mechanical stimuli, which is highly desired for wearable technologies49. The operating principle relies on two stationary electrodes fixed to the top and bottom of a device and a freestanding triboelectric layer that moves freely between them upon application of external mechanical energy that have been used in health monitoring applications50,51. As the movable layer approaches the stationary electrodes through contact-separation or sliding motions, periodic variations in the induced potential difference between the layers trigger the injection of free electrons through an external load, as seen in wind energy based TENG52, electronic skins (e-skins)53, and self-powered measurement-control combined systems consisting of advanced 2D materials54. Beyond its obvious useful functionality, as being a special mode of an energy conversion device, the freestanding triboelectric layer mode represents a significant technological innovation as witnessed in observation of charge transfer acceleration55 and fully self-powered vibration threshold monitoring56. The design developed for this mode is responsible for efficient energy conversion. Its broad applicability across diverse fields showcase how TENG technology can influence other technologies, such as contactless motion tracking57,58.

The versatility of TENGs, manifested through the aforementioned operational modes, empowers the efficient capture of mechanical energy in a multitude of forms. This capability translates into widespread applicability as various types of sensors, energy conversion systems, self-powered devices, and so on. The ongoing development of these technologies unlocks exciting possibilities for future advancements in energy harvesting and utilization. By harnessing these advancements, TENG hold immense promise to significantly contribute to a sustainable future across various fields, such as energy, health, textile, entertainment and similar, most importantly by being human- and environmental-friendly.

The operational modes described above are the most well-known modes of TENG. All these modes could be also applicable to other nanogenerators, such as PENG and could have important roles in wearable devices. Polymer nanofiber-based PENGs59,60 showed great promise in this respect. Also, in contact-separation mode, polymer-silver and polymer-graphene oxide composite nanofibers have been used as transparent electrode and tribo-layers in TENGs, respectively, with enhanced output characteristics61,62. In all these systems, the fabrication method of nanofibers relied on electrospinning, which stands as an efficient and promising technique to be more commonly used in wearable electronics, such as self-powered sensing63, human-machine interfacing in smart shoes64 and other textile-based electronics65, and biomechanical energy harvesting66.

Electrospinning technique to make nanofibers for TENG

Electrospinning stands as a cornerstone technique in making of fibers with exceptional control over material morphology at nanoscale. This versatile method relies on the application of strong electric fields to elongate, stretch, and solidify charged organic solutions, ultimately generating continuous ultrafine fibers with applications in various fields67, and recently showed great progress in polymer-based nanocomposite fibers10,61,62. The increase in surface to volume ratio due this technique also allows formation of various fiber structures, such as nonwoven, aligned, and patterned fiber meshes, as well as random assemblies68. There are various other spinning techniques in addition to non-spinning techniques that can yield nanofibers69. In this respect, electrospinning is advantageous over other spinning techniques like: melt spinning used in thermoplastics and nylons70, which require thermally stable polymers and complicated device preparation; blow-spun technique71,72, in which polymeric precursor, pressurized air, and collector assembly are used to collect irregular and relatively large diameter fibers; various solution spinning techniques73,74, in which fiber formation is controlled and limited by solvent evaporation, such as wet and dry spinning; and drawing75 (similar to dry-spinning), in which fibers are discontinuous, even though well-defined.

The electrospinning, that we focused in this review, is a solution-based process, which typically involves a multi-step sequence consisting of solution preparation, spinning, fiber elongation under strong applied electric field (in the order of 10 kV) through various kinds of needles (or nozzles), solidification, and solvent evaporation. Here, we emphasize that we will not delve into technical details and leave it to existing literature10,61,62,67,68,69,70,71,73,74,75,76,77; rather, we cover the outcome and scope of the process itself. This intricate process, results in the production of nanofibers with characteristic nanoscale dimensions in terms of radius. While there are various parameters being involved in the process and could be decisive in the final products’ almost all properties, electrospinning can be considered as a simple, effective fiber production method. It offers a multitude of advantages. Firstly, its relatively uncomplicated device setup and straightforward operational procedure translate to enhanced feasibility for practical applications. Secondly, electrospinning is able to render fine control over various process parameters, including voltage, flow rate, and solution properties. Therefore, precise tailoring of fiber diameter, morphology, and other critical characteristics that suit specific requirements can be easily realized67. Additionally, the extreme versatility of this technique allows processing of a broad spectrum of materials, ranging from polymers to biomaterials76; thereby, it is possible to significantly expand the application scope.

Electrospinning boasts impressive production rates, facilitating the efficient generation of large quantities of nanofibers, which is a crucial factor for mass production. Compared to alternative fabrication methods, electrospinning offers a cost-effective approach, demonstrating high economic viability and considerable potential for industrial-scale production20,21,69,70,71,73,74. Therefore, this technique has become a popular nanomaterial fabrication method to be used in a wide spectrum of nanogenerator devices77. Examples include encapsulated devices based on combination of nano-micro fibers of polymers with cooperating PENG and TENG functions78 and single-electrode mode bionic polymer nanofibers-based PENG mode79, as well as composite polymer-polymer blend nanofibers-based TENG80, in which mechanical robustness and durability can be outstanding.

Electrospinning technology plays a pivotal role in propelling high-performance flexible TENGs, by enabling the facile production of physically and chemically tailored components that are vital for efficient voltage and current generation. This is possible mainly because electro-spun nanofibers perfectly match with flexible substrates and electrodes within TENG, while preserving their main feature of high surface area and ductility. These attributes contribute to efficient charge transfer and accumulation with minimum loss. Furthermore, the incorporation of functional additives or nanomaterials into the polymer matrices of electro-spun composites and hybrids can enhance frictional interactions, charge transfer efficiency, and mechanical robustness, leading to a synergistic improvement in overall TENG performance77,81.

The fact that electro-spun nanofibers are soft but tough and not brittle, allowing air inside (breathability) without deformation, water-resistant, and being on substrates that permit electrical conduction make them ideal for wearable electronic applications82. This becomes more obvious and relevant by considering all possible TENG operation modes mentioned before (except sliding and freestanding modes, which have durability and wearing challenges in the case of electro-spun nanofibers near contacts) and selection of materials, namely polymer nanofibers to be used within TENG for high performance83. In this respect, flexible/wearable device examples of polymer-inorganic composite nanofibers-based mixed PENG-TENG84, layers of two polymers (far apart in the triboelectric series) nanofiber membranes-based TENG85, and polymer nanofibers used in a polymer matrix as self-powered e-skin86 have been inspiring works. The characteristics of durable conformity to human motion, blended with meticulous design and optimization of nanofiber structures, open windows for numerous useful aspects of wearable TENGs. Besides being a renewable energy source, they could function as eco-friendly sensing, monitoring, and interactive devices, since most electro-spun nanofiber materials have acceptable degradation lifetimes that are not been categorized as pollutants. Therefore, this synergistic integration of electrospinning technique with TENG development underscores the transformative potential of nanomaterials in ushering to the new era of sustainable energy solutions and next-generation wearable electronic devices29,30,82,83,84,85,86,87,88.

TENGs using electro-spun nanofibers for wearable electronics

The macroscopic output properties of TENGs, such as voltage, current, and power density, are dictated by a complex interplay of nanoscale factors, including surface characteristics and material properties. To achieve optimal TENG performance, researchers strategically have employed various nanofabrication and manufacturing techniques to tailor these critical aspects. Electro-spun nanofiber films, for instance, exhibit exceptional flexibility and lightweight, making them ideal candidates for wearable devices and flexible power sources87. Notably, for piezoelectric materials, the high electric fields and stretching forces inherent to the electrospinning process can significantly enhance material polarization. This phenomenon translates to improved piezoelectric performance in polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) films89,90, which can find various application possibilities91, including TENG, not only in film-based but also composite and/or hybrid nanofiber-based PVDF, in which both piezoelectricity and energy harvesting can be further enhanced92. Hence, electrospinning technology plays a critical role in the development of high-performance piezoelectric polymers by influencing not only their morphology and mechanical properties but also inducing favorable polarization through the application of strong electric fields.

The properties of electroactive components within nanofiber films evidently are expected to influence their overall characteristics, either by hybridizing or making composites. Recent research highlights the significant role of various synthetic polymers led by PVDF and its co-polymer (poly(vinylidenefluoride-co-trifluoroethylene), (P(VDF-TrFE)) in the development of TENG as electrode and tribo-layer materials91,93. Beyond their role in device performance, synthetic or natural electro-spun nanofiber films have attracted significant attention for their suitability in wearable applications due to their desirable biocompatibility, mechanical strength, antibacterial properties, breathability, and chemical stability. In the following subsections, recent research works about wearable electronic TENG devices made out of most commonly employed electro-spun nanofibers will be presented, starting with PVDF-based nanofibers as the exemplar platform for various aspects of smart textile applications.

Polyvinylidene fluoride and its co-polymers

Polyvinylidene fluoride, abbreviated as PVDF, stands out as a pivotal triboelectric material due to its high electron affinity, inherent spontaneous polarization, and stable dipole moment94. Moreover, its fascinating mechanical strength and flexibility make PVDF a perfect choice as a TENG dielectric layer. It exhibits five distinct crystalline polymorphs (α, β, γ, δ, and ε), with the β-crystalline phase being the most attractive one95, and it is the indication of high piezoelectricity (high piezoelectric coefficient). The application of a strong electric field during mechanical stretching process promotes the alignment of C-F dipoles in an all-trans conformation, thereby fortifying the β-crystalline phase and enhancing the dipole moment within PVDF films90,96. Also, recently it was shown that in TENGs based on PVDF films, it is possible to quantitively separate the piezoelectric component97. Furthermore, PVDF can be strategically co-polymerized with other monomers, such as trifluoroethylene (TrFE) and hexafluoropropylene (HFP), to tailor its performance characteristics in various forms, such as nanofibers, for specific applications98, such as highly sensitive acoustic sensors99 and self-repairing, hydrophobic, efficient water droplet energy harvester textile100. For instance, PVDF-TrFE, a co-polymer formed with TrFE and tetrafluoroethylene, exhibits ferroelectric properties, making it suitable for piezoelectric sensors and energy converters98. In contrast, PVDF-HFP, a co-polymer incorporating HFP, is recognized as a promising electroactive material for wearable TENG due to its outstanding mechanical flexibility, biocompatibility, chemical stability, and advantageous electronegative properties arising from the presence of fluorine moieties84,99,100. The versatility and tunability of these PVDF-based materials offer vast opportunities for advancements in electronic devices and energy converters. Especially, electrospinning process that is used in making of nanofibers based on PVDF, PVDF-TrFE, and PVDF-HFP has been a key tool to obtain unique structural properties, e.g., use of variety of nozzle combination to obtain segregated or mixed composite polyimide/PVDF-TrFE nanofibers enhancing TENG performance101. Consequently, this multifaceted fabrication technique renders nanofiber complexes highly valuable for wearable TENG applications3,6,29,31,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,91,98,102,103, such as sensing, human-machine interfacing, self-powered systems, and enhanced energy harvesting.

Wearable sensing

The conversion of mechanical energy from human motion into electrical energy by a TENG can be thought as a sensing capability to be used in wearable devices. This functionality can be seen as high responsivity to voltage or current fluctuations within a reasonable time period. In this sense, a flexible TENG can be an ideal wearable sensing device, with rapid response to subtle mechanical stimuli. In a very recent work104, Yang et al. have developed a high-performance flexible wearable sensor (HFWS) with breathable characteristics (Fig. 2a). The HFWS integrated in a film comprising of electro-spun, polarized PVDF-barium titanate (PVDF-BTO) nanofiber film and a nickel fabric electrode was strategically positioned on various parts of body. This sensor effectively monitored corresponding motion signals104. Similarly, Yang et al. pursued a yarn-based approach105, creating a sheath-core structure combining PVDF/graphene (G) with carbon fiber (CF) via conjugate electrospinning (Fig. 2b). This design incorporated a commercially available CF core encapsulated within an electro-spun sheath of G-doped PVDF nanofiber film. This configuration enhanced the fatigue resistance of electro-spun nanofiber films during extended periods of friction while preserving flexibility. When integrated into wearable devices for sportive activities, these yarns generated electrical signals upon activation by body movements such as bending limbs or walking. These signals hold promise for various wearable sensor applications105.

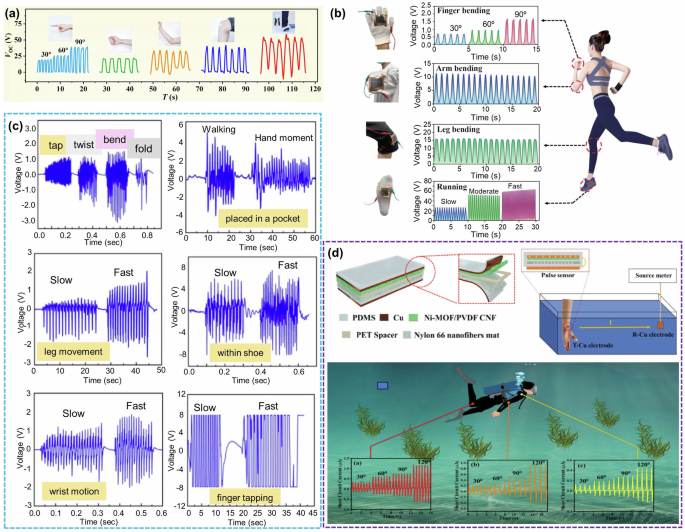

a Open circuit voltage (Voc) of a high-performance flexible wearable sensor (HFWS) TENG, consisting of PVDF-barium titanate nanofiber film against Ni fiber film in contact-separation mode, attached to different parts of human body. Reprinted with permission104. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. b Human motion monitoring and signal transmission using graphene and carbon fiber doped PVDF nanofiber film in a single-electrode mode TENG-based textile used in various parts of body during sportive activity. Reprinted with permission105. Copyright 2024, Tsinghua University Press. c Versatile TENG in contact-separation mode, consisting of a tribo-negative layer of PVDF nanofibers doped with P-Si.HBP-G3 (silane-based hyperbranched polyester of the 3rd generation) against melt-blown thermoplastic urethane layer, used as a sensor in harnessing biomechanical energy from various human motion activities. Reprinted with permission106. Copyright 2024, Elsevier B.V. d Single-electrode TENG consisting of PVDF/MOF composite electro-spun nanofiber film for acquiring biomechanical energy and monitoring joint movements due to its exceptional shape adaptability. Reprinted with permission107. Copyright 2023, Wiley.

Indumathy and Prabu further expanded the potential of hybrid PVDF nanofibers-based TENG in wearable electronics. They fabricated electro-spun nanowebs composed of blends of PVDF and silane-based hyperbranched polyester of the 3rd generation (Si.HBP-G3) to be used as tribo-negative layer in TENG against melt-blown thermoplastic urethanes (TPU) nonwoven fabric layer in contact-separation mode. This TENG exhibited exceptional adaptability to diverse physical deformations during usage in different parts of clothes and shoes, making them suitable for wearable device operations (Fig. 2c)106. In another work, Das et al. explored the application of TENG in underwater environments by demonstrating a single-electrode triboelectric nanogenerator (S-TENG), making use of composite nanofibers based on PVDF, carbon nanofibers (CNF, and Ni based metal-organic framework (MOF), designed to function as a wireless sensor in sea environment107. This sensor deployed the Maxwell’s displacement current concept and was intended to use on scuba divers to monitor arterial pulse and body movements, while being underwater, for safe diving purposes. Therefore, S-TENG is a valuable tool for diving activities to track divers’ underwater motions (Fig. 2d).

Human-machine interaction (HMI)

Among many candidates, TENG have emerged as revolutionizing HMI tool due to easy-integration and compatibility feature, while keeping high sensitivity mentioned earlier. This capability empowers TENG as devices being able to detect specific motions and touches in a smart way. These sensors can be integrated into touch-based control interfaces or gesture recognition systems, fostering intuitive user interaction with electronic devices. The lightweight and flexible nature of TENG facilitates their seamless integration into various surfaces and structures for usage at home or office. These characteristics allow incorporation of TENG inside buildings, on or within, such as furniture and flooring with modifications favoring AI-based minimalism108,109. By collecting ambient mechanical energy, TENG acts as a green energy source, offering energy-saving within buildings. This innovation reduces reliance on conventional power sources87, ultimately promoting automation and convenience.

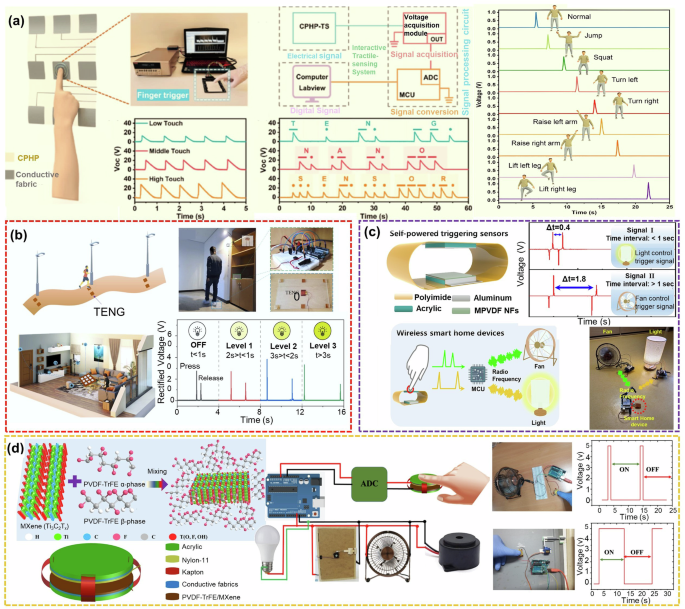

Within last couple of years, Niu et al. conducted research on the development of a high-performance TENG with a single-electrode configuration110. Their innovation centered on a cellulose nanocrystal (CNC)-reinforced PVDF hybrid paper (CPHP) by using electrospinning. This CPHP-based TENG exhibited robust output performance, paving the way for its integration into a self-powered tactile sensor (CPHP-TS). Notably, the CPHP-TS was consistently integrated into a virtual environment, enabling intuitive game control through character movement manipulation (Fig. 3a)110. In another work, Pandey et al. made significant step forward in the development of smart home and street control by introducing nafion-functionalized BTO nanoparticles BaTiO3 NPs/PVDF composite nanofibers-based high-performance triboelectric nanogenerator (NBP-TENG) (Fig. 3b)111. This TENG functioned as a human-machine interface, controlling street lights and household appliances upon integration with a signal conversion system and microcontroller unit. Sohn et al. further expanded the applications of TENG in smart homes by engineering MOF-based composite PVDF nanofibers (MPVDF NFs) as a trigger system (Fig. 3c) device112. It was possible to demonstrate that MPVDF TENG can control a fan and a room light simultaneously, emitting distinct signals to trigger separate electronics from a single device. In a more fundamental study, Rana et al. explored the potential of PVDF-TrFE/MXene nanocomposite materials for TENG development113. They successfully fabricated an electro-spun nanofiber-based TENG (EN-TENG), consisting of PVDF-TrFE/MXene nanocomposite nanofiber tribo-negative layer against nylon 11 nanofiber layer, capitalizing on PVDF-based nanocomposite layer’s superior dielectric constant and high surface charge density. By leveraging the advantages of EN-TENG, they designed a smart switch for home appliances, demonstrating versatility of flexible TENGs in proof-of-concept wearable electronic applications (Fig. 3d).

a Flexible cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs)-reinforced PVDF hybrid nanofiber paper (CPHP)-based single-electrode TENG acting as self-powered tactile sensor (CPHP-TS) for game control systems with well-defined character movements shown on the right. Reprinted with permission110. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH GmbH. b Implementation of a composite BaTiO3/PVDF nanofibers-based TENG in contact-separation mode against a Cu layer, in a smart street and home control system with a smart triboelectric switch. Reprinted with permission111. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. c Integration of a metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)-based composite PVDF nanofibers (MPVDF NFs)-based TENG, in contact-separation mode against an Al layer, into a smart home control system. Reprinted with permission112. Copyright 2023, Elsevier B. V. d Utilization of an electro-spun nanofiber-based TENG (EN-TENG), consisting of PVDF-TrFE/MXene nanocomposite nanofiber tribo-negative layer against nylon 11 nanofiber layer, as a self-sustainable power source for driving electronic devices in smart home applications by scavenging biomechanical energy. Reprinted with permission113. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society.

Self-powered devices

Sensors based on TENGs shine with their compact size, lightweight design, and high-resolution responsiveness to a variety of stimuli, including touch, motion, and vibrations. These attributes have been sought as an opportunity to be used as continuous power supply in device integration strategies11 and energy autonomy3. Fortunately, a TENG sensor, in accordance with environmental sustainability, can operate as a renewable energy source provided by its own, which makes it a self-powered device. The integration of wearable TENG devices and its IoT applications are vital for energy-efficient sustainable future and there has been important progress in terms of fiber-based systems114.

As one of pioneering works, Huang et al. developed a novel single-layer binary fiber nanocomposite membrane (SBFNM) for multifunctional self-powered TENG sensor device115. This membrane, fabricated via co-electrospinning of PVDF/CNTX with PAN/CNTX; labeled as DPCPCX, where CNTs are carbon nanotubes, PAN is polyacrylonitrile, and “x” is the CNT content in PVDF and PAN, with values can be ranging from 0.25 to 1.5 wt%. The SBFNM-based TENG mentioned above exhibited exceptional durability of 5000 cycles and long stability of 3 months, indicating self-sufficiency as a self-powered sensor, which could find ways in applications, such as night-time safety alarm for various surveillance needs (medical, building safety, and so on). For illustration purposes, a single-chip microcomputer alarm device was used to demonstrate a self-powered sensing system (Fig. 4a)115.

a Wearable TENG consisting of single-layer binary fiber nanocomposite membranes (SBFNMs) by co-electrospinning of PVDF with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and polyacrylonitrile (PAN) with CNTs with Cu electrodes at the top and bottom, for self-powered wearable sensors demonstrated as single-chip microcomputer alarm device. Reprinted with permission115. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. b Triboelectric-generating soft actuator (TEG-SA) as self-powered wearable heat sensor based on TENG with PVDF nanofiber layer against nylon 6/6 film layer, collecting data as open circuit voltage (Voc). Reprinted with permission116. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. c Fire alarm system integrating a highly flexible and self-powered thermal sensor (FSTS) based on a TENG (using a flexible printed circuit board (PCB) between PDMS and PVDF-TrFe micro/nano fibers layers) with a LED. Reprinted with permission117. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. d Ultra-stretchable, waterproof, and air-permeable PVDF-HFP/SEBS nanofibers-based TENG (PHS membrane) acting as highly sensitive self-powered electronic skin (e-skin) TENG was demonstrated. Reprinted with permission118. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd.

In another case, a natural heat-dependent self-powered sensing device was reported by Zhang and Yuan116, in which a triboelectric-generating soft actuator (TEG-SA) with a hollow bilayer structure was used for temperature sensing (Fig. 4b). This actuator basically made up of a TENG consisting of PVDF nanofibers film on a liquid crystal elastomer (LCE) and nylon 6/6 film on a conducting tape. The LCE is deformed by heat, prompting the TENG tribo-layers to generate electrical signals via triboelectric effect between PVDF and nylon 6/6. These signals can be further processed to trigger light and sound alarms116. This kind of system can be categorized as self-powered wearable heat sensor. As another self-powered heat sensing example, Shie et al. developed a fire alarm system that integrates a highly flexible and self-powered thermal sensor (FSTS) with an LED (Fig. 4c)117. This system incorporated several key features: a graphene-modified intumescent flame retardant (GIFR) coating layer, self-powered PVDF-TrFE micro/nano fibers (MNFs) deposited by near-field electrospinning74,93,117,118, and an electrostatic friction layer created using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) rolling-over technology, which separates MNFs by a flexible printed circuit board (PCB). Encapsulated within the GIFR coating, the MNFs functioned as a motion-induced vibrational energy harvester, powering the entire self-powered fire alarm system117.

In an earlier work, the challenges of elasticity, breathability, and waterproof functionality in wearable self-powered sensing was addressed by developing an ultra-stretchable, waterproof, and air-permeable textile TENG via the electrospinning of PVDF-HFP/ styrene–ethylene–butylene–styrene (SEBS) (simultaneous electrospraying of SEBS microspheres) by utilizing physical interlocking strategy118. A stretchable nanofibers-based TENG (SNF-TENG) device in single electrode mode (e-skin) with printable electrode consisting of liquid metal (LM) (gallium indium tin particles) and silver flakes, sandwiched between SNF layer and a SEBS substrate, labeled as PHS membrane (PVDF-HFP/SEBS) and this self-powered e-skin exhibited strong electrical durability (Fig. 4d). It was attached on a finger and the output voltage values yielded similar negative and positive values, indication of mixed contact-separation TENG mode. This textile-based design is able to capture the finger touch behavior real-time as a self-powered security or entertainment system118,119. This clever approach can open up new avenues in wearable self-powered sensing technologies.

Amplified energy harvesting

Nanofibers amplify the voltage and current output obtained out of TENG devices, namely, they make output values much larger compared to those that would be obtained from bulk film forms. Therefore, as the primary goal of renewable energy source, enhanced energy harvesting from small mechanical movements via nanoscale triboelectric effect can be realized. In the field of wearable electronics, this clear advantage allows TENG to effectively capture energy from human motion, vibrations, wind, water flow, and other environmental sources, when it is a part of textile or home/office indoor/outdoor appliances, and so on. For instance, Jiang et al. achieved a significant breakthrough by engineering a stretchable, breathable, and stable nanofiber composite (LPPS-NFC) using a lead-free perovskite/PVDF-HFP-SEBS blend via electrospinning120. The triboelectric-piezoelectric nanogenerator (T-PENG) developed in this project, effectively harvested energy, when it was placed inside a shoe pad (T-PENG operated in contact-separation mode as in Fig. 5a). Inorganic perovskites incorporation increased the charge trapping capacity of the composite nanofibers, and simultaneously enhanced the β phase of PVDF-HFP. As a result, the charge transfer efficiency of the LPPS-NFC in the T-PENG has improved due to the synergy between tribo- and piezo-electric effects.

a Visualization of energy harvesting from various human motions, with the specific example of a shoe pad, from lead-free perovskite/PVDF-HFP-SEBS-based nanofiber composite (LPPS NFC) used as a triboelectric-piezoelectric nanogenerator (T-PENG) in contact-separation mode and charge transfer efficiency was increased compared to PENG mode. Reprinted with permission120. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH GmbH. b Enhanced energy harvesting out of a TENG consisting of polyurethane (PU) film and a tribo-negative layer of PVDF nanofibers mixed with second-generation aromatic hyperbranched polyester (Ar.HBP-G2), labeled as PAG2 and 10 wt% yielded the largest output. Reprinted with permission121. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. c Biomechanical energy harvesting and monitoring from a wearable TENG consisting of hybrid Cs2InCl5(H2O)@PVDF-HFP nanofibers (CIC@HFP NFs) tribo-negative layer against nylon 6,6 nanofiber layer. Reprinted with permission19. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. d Washable fibrous WF-TENG integrated into a face mask to collect energy from breathing. Reprinted with permission122. Copyright 2023, The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd.

Furthermore, it was possible to carry out healthcare monitoring by energy harvesting from contact-separation mode TENG consisting of two tribo-layers of polyurethane film and a tribo-negative film of PVDF nanofibers mixed with second-generation aromatic hyperbranched polyester (Ar.HBP-G2), labeled as PAG2 with varying Ar.HBP-G2 ratios (largest output obtained at 10 wt%). The TENG was placed in various parts of human body to collect signals 15 times larger than then PENG only version121, as shown in Fig. 5b. In another work, core-shell and biocompatible hybrid Cs2InCl5(H2O) doped PVDF-HFP nanofibers (CIC@HFP NFs) fabricated through one-step electrospinning assisted self-assembly, and was used as tribo-negative layer against nylon 6,6 nanofibers as tribo-positive layer in contact-separation TENG mode. This all-fiber-based biocompatible TENG effectively converted random walking energy to power up stopwatches and calculators, as seen in Fig. 5c, due to the crystalline polarized phase enhancement of PVDF with perovskite nanofiller in electrospinning process19. Although in applications shown in Fig. 5c, the output voltage values are few volts, this TENG reached to 681 V and 53.1 μA, which are the highest reported values for halide perovskites-based TENGs. Khanh et al. brought gain in energy harvesting by nanofibers to another level, by developing a washable and self-healing fibrous triboelectric nanogenerator (WF-TENG) using PVDF nanofibers and polybutadiene-based urethane (PBU) fibers. The output power of this highly-functional and industrially-feasible design was quite high (1.14 W.m−2) and was integrated into face masks, enabling energy harvesting from user’s breathing cycles (Fig. 5d)122.

Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)

As a synthetic polymer composed of repeating acrylonitrile units, polyacrylonitrile (PAN), is a common raw material in many industries due to its chemical and thermal stability, high mechanical strength, and ability to make blends and composites with a variety of materials123. Its cost-effectiveness and ability to generate fine fibers (tens to hundreds of nanometers in diameter) are the main reason for widespread use, including TENG devices, as mentioned earlier in composite PAN/CNT nanofiber-based TENG115. These properties make PAN a preferred material for nanofiber production via electrospinning124, and TENG devices made out of pure electro-spun PAN nanofibers perform much better than spin-coated PAN. Efficient charge separation can take place with a tribo-layer consisting of PAN-based nanofiber films with appropriate opposite tribo-layer in a TENG. Similar to PVDF, PAN can be taken as an ideal platform for wearable TENG applications, as it was demonstrated in PVDF incorporated in PAN piezoelectric elastomers acting like artificial skin125.

Recently, it has been reported that PAN nanofibers electro-spun with succinite and SiO2 particles can yield large and Young’s modulus (elasticity)126. On the other hand, although PAN itself doesn’t possess high piezoelectricity, when it is electro-spun with PVDF it exhibits even much higher piezoelectricity than pure PVDF nanofibers127, due to PAN’s sawtooth planar conformation. Also, in a noise harvesting device based on PAN/PVDF nanofibers, it was possible to effectively convert the noise-to-electricity due to triboelectric effect within the nanofiber membrane128. All these observations indicate that electro-spun PAN nanofibers-based membranes can find applications as self-powered sensors and energy harvesters in diverse fields, including healthcare monitoring and environmental sensing. One of the most recent examples of PAN nanofibers usage as TENG material is the work reported by Varghese et al., in which they used PAN nanofibers layer against PDMS layer and developed a self-powered obstacle detection system using a triboelectric artificial whisker (TAW) (Fig. 6a)124. In this work, a motion sensor was developed that generates an electrical signal upon mechanical contact with an obstacle during navigation124.

a Obstacle detection system using a triboelectric artificial whisker (TAW) sensor (using a contact-separation mode TENG consisting of tribo-positive PAN nanofiber layer against PDMS layer) with large open circuit (Voc) that was generated upon obstruction triggered by finger motion. Reprinted with permission124. Copyright 2023, Wiley-VCH GmbH. b All-nanofiber-based single-electrode TENG, consisting of TiO2/PAN composite nanofiber film as active layer and Ag nanowires/thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) nanofibers as electrode material, integrated into a self-powered pedometer for real-time movement tracking. Reprinted with permission129. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society. c Self-powered filter utilizing a TENG consisting of electro-spun polybutanediol succinate (PBS) nanofibers film and PAN/polystyrene (PS) nanofibers film for air purification. Reprinted with permission130. Copyright 2023, Donghua University, Shanghai, China. d Self-powered visible light communication (VLC) system for wireless human-machine interaction based on a PZ-TENG, consisting of zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) as nanofillers in PAN, “PAN@ZIF-8 nanofiber” layer against tribo-negative PTFE film layer. Reprinted with permission131. Copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V. e Self-charging power system utilizing a TENG, consisting of PAN nanofiber-based composites against tribo-positive nylon 66 nanofiber film layer, for energy harvesting and powering an LED. Reprinted with permission132. Copyright 2022, The Authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

In an earlier work, Jiang et al. designed a multifunctional (single-electrode) TENG by engineering three layers of films, in which two nanofiber films separated by water-proof PTFE layer129. This light-sensitive TENG had several features, such as UV-protection, self-cleaning, and antibacterial (Fig. 6b). In addition to silver nanowires/TPU nanofiber layer as electrode, TiO2@PAN nanofiber networks had the role of active layer. Notably, this TENG effectively monitored human motion and was integrated into a self-powered pedometer for real-time movement tracking129. From a different point of view, Yang et al. explored the triboelectric charging in a self-powered filtration system. They developed air purification filter utilizing a TENG consisting of electro-spun polybutanediol succinate (PBS) nanofibers film (tribo-positive layer) and PAN/polystyrene (PS) nanofibers film (tribo-negative layer), as shown in Fig. 6c, with large filtration efficiency130. Also, for specific self-powered sensing purpose, Pandey et al. prepared a PZ-TENG, consisting of zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) as nanofillers in PAN, “PAN@ZIF-8 nanofibers” as tribo-positive layer and PTFE film layer tribo-negative layer (Fig. 6d). They obtained three times larger output voltage compared to PAN nanofibers without ZIF-8131. The most important outcome of this work was the development of a self-powered visible light communication (VLC) system for wireless HMI, showcasing impact of nanofillers in nanofibers for wearable TENG to be used in security, defense, home, and surveillance applications131. In an attempt to make a self-charging power system, a TENG and a supercapacitor made out of PAN nanofibers film and polyaniline (PANI)-coated PAN nanofiber membrane, respectively, were utilized by Park et al.132. They integrated the electro-spun PAN nanofiber-based composites as one layer of TENG and electro-spun nylon 66 nanofiber film as the tribo-positive layer of TENG and stored energy right after generation using (PANI)-coated PAN nanofiber membrane (Fig. 6e). This design resulted in a self-charging power system capable of illuminating a commercial LED, highlighting the potential of TENG for sustainable power generation132.

Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU)

The thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) is a heat-sensitive polymer known for its porous structure, elasticity, durability, and its ability to interlock with materials like graphene to become more compressible and exhibit stable piezoresistive sensing133. When it is used as TENG layer, a TPU film, with its spongy nature, can lead to an enhancement in TENG output, such as in the case of TPU-making composite with ferroelectric BTO-coupled 2D MXene, in which coupling with MXene increases the dielectric constant and the dielectric loss is lowered via coupling with the BTO134. Also, a more specific application of TPU in wearable electronics was reported135 in respect to efficient energy harvesting in a TENG in contact-separation mode, in which TPU-coated yarn (tribo-positive) was used against PDMS-coated yarn (tribo-negative) as tribo-layers. Moreover, as self-powered e-skin application, an ultra-stretchable triboelectric nanogenerator (S-TENG) consisting of a membrane with alternative layers of electro-spun TPU microfibers and Ag nanowires mixed with reduced graphene oxide (rGO) conductive layers was constructed for energy harvesting and tactile sensing136.

The most important TENG feature of TPU is its hydrophobicity, which is appealing for textile-based electronics. Electrospinning of TPU into nanofibers yields membranes with a high surface area, nonwoven properties, and interconnected structure, being resistant to water and sweat. This has a critical role in TENG fabrication process and can make TENG an efficient energy harvester as well as a self-powered sensor. Inspired by plant water transport systems, Cheng et al. designed a two opposite wettability (Janus) textile-based single-electrode triboelectric nanogenerator (J-TENG) (Fig. 7a) using TPU nanofiber film as near skin hydrophobic layer137. This innovative textile exhibited directional moisture transport, with simultaneous vibrational energy harvesting and motion sensing. The J-TENG featured a double gradient in pore size and wettability, which was achieved through a hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile (HPAN)/hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets (BNNS) fibrous membrane laminated on top of TPU nanofiber layer. The HPAN/BNNS layer facilitated moisture wicking away from the body, while the TPU layer prevented sweat from returning, ensuring skin dryness during operation137. Also, thanks to TPU nanofibers’ elastic properties, it was possible to translate object handling operation into TENG voltages, as demonstrated by Li et al.138. They integrated mica (a material with highest triboelectric charge density) nanosheets with electro-spun TPU nanofibers against tribo-negative PVDF/MXene nanofiber film, in single-electrode mode of the TENG for sorting objects based on gripping strength (Fig. 7b)138. Water-contact angle measurements showed no variation for all mica concentrations, confirming the role of hydrophobicity of TPU138. Moreover, regarding e-skin applications, tactile sensing was realized by Jiang et al. with a stretchable, washable, and ultrathin skin-inspired TENG (SI-TENG) (Fig. 7c)139, consisting of a membrane of PDMS electrification layer, TPU/AgNWs composite electro-spun nanofiber layer, and VHB insulating tape, connected to signal processing circuit. This SI-TENG functioned in single-electrode mode, it was a highly sensitive self-powered haptic sensor, capable of harvesting human motion energy as well as recording kinesthesia.

a Janus textile-based triboelectric nanogenerator (J-TENG, in single-electrode mode), consisting of hydrophilic hydrolyzed polyacrylonitrile/hexagonal boron nitride nanosheets on top hydrophobic TPU nanofiber layer, for directional moisture transport and self-powered motion sensing. Reprinted with permission137. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. b Utilization of a contact-separation mode TENG, consisting of composite electro-spun TPU/mica nanosheets-based nanofibers against tribo-negative PVDF/MXene nanofiber film, for self-powered body motion monitoring and robotic sensing using. Reprinted with permission138. Copyright 2023, The Author(s). Published by Elsevier Ltd. c Demonstration of skin-inspired, washable SI-TENG in single-electrode mode, consisting of a membrane of PDMS electrification layer, TPU/AgNWs composite electro-spun nanofiber layer, and VHB insulating tape, connected to signal processing circuit to be used as self-powered haptic sensing translated from human motions via SI-TENG. Reprinted with permission139. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

Since TPU can easily make composite with various materials, it has diverse applications in its electro-spun nanofiber form that can be used in TENG-based wearables. A breathable and antibacterial TENG, made out of electro-spun TPU nanofiber layer and poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan (PVA/CS) nanofiber layer, separated by electro-sprayed Ag nanowire layer by Shi et al.140 was developed. In that work, TPU layer acted as sensing layer and thermal-moisture provider, Ag nanowires as electrode, and PVA/CS layer as antibacterial layer; and as a result, this self-powered e-skin was used in sportive activities for analytical purposes and sportsmen evaluations (Fig. 8a). With a motivation of understanding the effect of dielectric and thickness on TENG performance, composite TPU nanofibers with LM particles were studied by Song et al.42. They observed enhancement in TENG output voltage both by thickness and amount of LM nanofillers within TPU nanofibers. They designed a LM-TENG operating in contact-separation mode for a smart door lock system (Fig. 8b). This LM-TENG offered an enhanced security through password privacy and anti-peeping features enabled by case-sensitive sliding patterns42. In another thickness study, Oh et al. found out the enhanced energy harvesting in so-called N-TENG, consisting of TPU nanofibers with nonwoven (N) relatively more porous polypropylene (PP) nanofillers, with Ni-coated fabric as top and bottom electrodes. Much thicker TPU/PP layer yielded much larger voltage compared to that without PP and used as insole (Fig. 8c)141.

a A breathable and antibacterial TENG consisting of electro-spun TPU nanofiber layer and poly(vinyl alcohol)/chitosan (PVA/CS) nanofiber layer, separated by electro-sprayed Ag nanowire layer, operating in single-electrode mode placed on arm used for sportive activity data collection. Reprinted with permission140. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. b Liquid metal (LM)/TPU composite nanofibers-based TENG employed as a password system for anti-peeping smart door locks. Reprinted with permission42. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. c Demonstration of enhanced energy harvesting in composite TPU nanofibers with nonwoven polypropylene (PP) nanofillers-based TENG, operating in contact-separation mode with Ni-coated fabric as electrodes, with increased thickness of TPU layer. Reprinted with permission141. Copyright 2020, The Authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland.

Nylon

Nylon is a widely used synthetic polymer made out of polyamide. It is known for its unique mechanical properties, including toughness, elasticity, and resistance to abrasion and chemicals. Electrospinning is one of the standard methods to produce nylon nanofibers with diameters ranging from nanometers to micrometers142. The electro-spun nylon nanofibers possess a high surface-to-volume ratio and an interconnected porous structure, allowing hybridized nylon nanofibers; and they emerged as a promising material for TENG particularly due to rare tribo-positive nature unlike many other tribo-negative polymers. As studied just recently by Jelmy et al.143, a TENG based on tribo-positive electro-spun nylon 6 nanofibers and tribo-negative fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP), in contact-separation mode, was found to be useful for breath sensing (Fig. 9a). This wearable belt-integrated TENG enabled monitoring of breath patterns, highlighting its potential in healthcare applications143.

a Breath-sensing wearable belt fabricated using electro-spun nylon 6 nanofibers and fluorinated ethylene propylene (FEP) for monitoring breath patterns. Reprinted with permission143. Copyright 2024, The Author(s). Published by IOP Publishing Ltd. b A TENG composing of nylon 12/A-rGO nanofiber films, where A-rGO is hybridized rGO, against tribo-negative layer of EcoFlex/MoS2 composites for a flexible triboelectric sensor (TES) applicable in human-machine interfaces and child tracking alarms. Reprinted with permission144. Copyright 2024, Elsevier Ltd. c HM-TENG utilizing nylon/L-cystine composite nanofibers layer against FEP film for efficient biomechanical energy harvesting. Reprinted with permission145. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. d Schematic of a self-powered triboelectric sensor (TES) consisting of a contact-separation mode TENG using a composite nylon 11/ poly L-lysine (PLL) nanofiber membrane against EcoFlex/SrTiO3 composite layer for measuring human activities via a wireless system. Reprinted with permission146. Copyright 2023, Published by Elsevier Ltd. e All-textile TENG, incorporating MXene-doped PVDF nanofiber tribo-negative layer against antibacterial Ag@nylon 6/6 nanofiber layer, and making self-powered tactile sensor arrays (SPTSA) for gesture recognition and tactile sensing via 9 sensors as HMI application (e.g., letters A, B, and C can be specifically typed with varying amplitude). Reprinted with permission7. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. f Ultra-sensitive acoustic sensor made out of contact-separation TENG using two layers of nylon nanofiber films with different surface potentials (labeled as S-TENG since only single (S) material was used) for voice signal recognition. Reprinted with permission147. Copyright 2022, Wiley-VCH GmbH.

The versatility of nylon nanofibers being either hybrid or composite can have high value and various TENG applications can be realized. It is important to identify what can nylon-based hybrid nanofibers bring into wearable TENG technology compared to composite ones. A research group prepared 2D amino-functionalized reduced graphene oxide (A-rGO) (hybridized rGO), to be electro-spun with nylon 12 as tribo-positive layer, used against tribo-negative layer of EcoFlex/micro-patterned molybdenum disulfide (MoS2) composite film144. Their characterization showed that A-rGO improved nylon 12 properties, which led to high TENG output performance in contact-separation mode. As shown in Fig. 9b, this TENG acted as a flexible triboelectric sensor (TES) and HMI device, for remote child surveillance144. In another work, highly efficient, high output biomechanical energy harvesting in a folded and multilayered TENG (HM-TENG, where H stands for high output and M for multilayer), consisting of nylon 6/L-cystine composite nanofiber film (NCNF) against FEP film (tribo-negative layer), was obtained without changing properties of nylon 6 (Fig. 9c)145. This HM-TENG was used as self-powered device, like thermometers and pedometers.

Also, a TENG-based sensor without spacer (in contact-separation mode) consisting of nylon 11 nanofiber membranes modified by poly L-lysine (PLL) (PNy11) tribo-positive layer against EcoFlex and 10 wt% SrTiO3 composite (EC10S) tribo-negative layer was used to monitor human activities via a wireless transfer system (Fig. 9d)146. In another study, Ag nanoparticles doped nylon 6/6, Ag@nylon 6/6 composite nanofiber layer (tribo-positive) against a hybrid PVDF (doped with MXene) nanofiber film layer (tribo-negative), was also used as an all-textile TENG for motion detection, as shown in Fig. 9e, in the form of self-powered tactile sensor arrays (SPTSA) where tactile sensing was realized via 9 sensors (e.g., ABC with varying amplitude for one of the sensors)7. These two works7,146, with composite-composite and composite-hybrid nanofiber structures with nylon being tribo-positive layer, contributed to the development of more robust and functional wearable TENG for gesture recognition and tactile sensing applications. Nylon is an extremely sensitive platform in terms of electrospinning parameters, as it was shown by Babu et al. in measurements of surface potential147. They designed an ultra-sensitive acoustic sensor based on a contact-separation TENG using two layers electro-spun nylon nanofibers with different surface potentials, as produced during electrospinning process by varying applied voltage. This sensor, which was labeled as S-TENG (since only a single (S) material was used), was quite effective on a facemask in voice signal recognition (Fig. 9f). This worked demonstrated the easily-adjustable nature of nylon nanofibers by electrospinning directly reflected on applications, in addition to making composites and hybrids.

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)

PVA is a versatile and water-soluble synthetic polymer with high mechanical strength, good biocompatibility, and non-toxicity. These properties make PVA a preferred biomaterial148,149,150 and can be used in biomedical device applications151,152. The electrospinning of PVA has led to new advantages in TENG performance. Since PVA is usually hydrophilic, it could affect the response to water of a composite materials consisting of PVA nanofibers, which could play a crucial role in TENG-based textiles. The combination of PVA nanofibers with complementary materials in TENG has led to the development of innovative self-powered systems for energy harvesting and sensor applications.

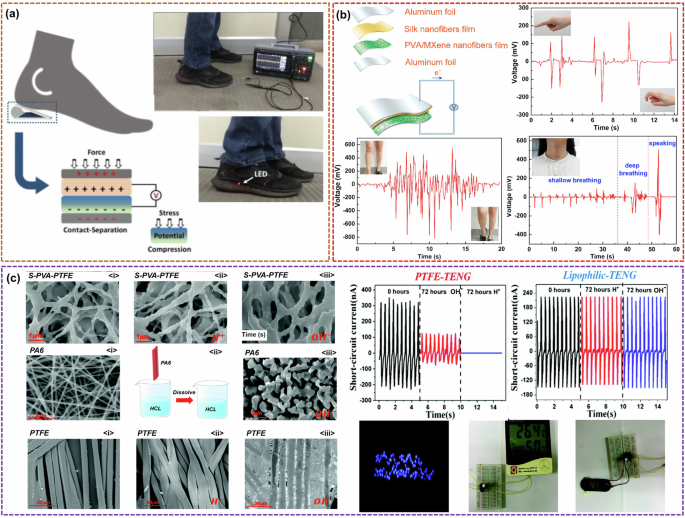

Electro-spun PVA nanofibers have been used by Sardana et al.153 as a flexible and compressible triboelectric nanogenerator (FC-TENG) for insoles, by incorporating lead-free dielectric material, potassium sodium niobate (KNN), embedded with Ti3C2Tx MXene fillers into a PVA matrix via electrospinning as one layer (electron-acceptor) and a cellulose nanofiber (electron-donor) another layer in contact-separation mode, as shown tribo-negative bottom layer and tribo-positive top layer, respectively, of the TENG in Fig. 10a. This FC-TENG effectively harvested energy from walking and other movements, showcasing its potential for wearable energy harvesting applications153. In another work154, a TENG, which was made out of a composite of MXene fillers in PVA nanofiber matrix was used as tribo-negative layer against the other layer of silk fibroin (SF) (as an electron donor) as tribo-positive layer, bottom and top, respectively in Fig. 10b. The result was the enhancement of triboelectric output with a peak power density of 1087.6 mW/m2 at 5.0 MΩ load resistance, while biocompatibility, stability, and durability were maintained. It was possible to obtain real-time monitoring of various body motions using self-powered sensor based on this TENG (Fig. 10b)154. Wu et al. had a different approach in usage of PVA nanofibers in TENG155. In their work, they tackled TENG contamination and corrosion challenges by developing a super-hydrophobic sintered PVA-polytetrafluoroethylene (S-PVA-PTFE) composite membrane via electrospinning and sintering processes. A TENG consisting of relatively tribo-positive industrial oil-absorbing paper against S-PVA-PTFE nanofiber layer was capable of powering electronic devices even after prolonged exposure to harsh conditions, including immersion in strong acid (hydrochloric acid, HCl) and alkali (sodium hydroxide, NaOH) solutions. This exemplified how normally hydrophilic PVA can be modified by making composites: becoming a super-hydrophobic material and act as a robust TENG to be used in harsh-condition wearables155, such as in chemical factories (Fig. 10c).

a Flexible and compressible triboelectric nanogenerator (FC-TENG), consisting of a tribo-negative (bottom) layer of PVA nanofiber with potassium sodium niobate (KNN) embedded with Ti3C2Tx MXene fillers, against cellulose nanofiber tribo-positive (top) layer, integrated into an insole for energy harvesting during walking. Reprinted with permission153. Copyright 2023, The Author(s). Published under an exclusive license by AIP Publishing. b All-electro-spun TENG with MXene nanosheets fillers in PVA nanofiber film and silk fibroin (SF) layer, for real-time monitoring of breathing and speaking. Reprinted with permission154. Copyright 2019, Elsevier Ltd. c Robustness to acid (H+) and alkali (OH−) of sintered PVA-PTFE (S-PVA-PTFE) nanofibers layer based TENG (lipophilic, against tribo-positive oil-absorbing layer), as shown by SEM images, while polyamide 6 (PA6) and PTFE-based TENGs degrade rapidly as seen by short-circuit current output and demonstrated energy harvesting. Reprinted with permission155. Copyright 2020, The Royal Society of Chemistry.

Silk

Silk, a natural protein fiber derived from silkworms and spiders, is renowned for its exceptional mechanical strength and biocompatibility156, making it suitable for various flexible electronic applications157. Silk nanofibers are essential wearable electronic materials and were studied in detail158, including self-powered nanogenerators159. Electrospinning allows silk to be processed into nanofibers, paving the way for the development of platforms like TENGs for wearable electronics for energy harvesting from human motion and environmental interactions. Here, we will mention some recent important works related to silk nanofibers’ strong ability as electron donor, their biocompatibility and ability to make composites160, and configurability of mechanical strength.

Guo et al. studied output performance and sensing applications of a TENG consisting of a tribo-positive layer of silk nanofibers mixed with poly (ethylene oxide) (PEO) against tribo-negative layer of PVDF nanofibers161. In this pioneering work, they were able to separate piezoelectric and triboelectric effects on TENG performance and find out hybrid piezoelectric-induced triboelectricity and labeled as TPNG, in contact-separation where they obtained enhanced output values. Additionally, they were able use this hybrid TPNG in integration mode, in which two layers stayed together unlike separation mode, sensing system. The hybrid TPNG acted as self-powered body motion detection via an automated system (Fig. 11a)161. They demonstrated that TPNG in separation mode can be used for versatile healthcare applications, such as person’s fall detection and posture monitoring161. In the other work, Su and Kim explored the use of silk nanofibers mixed with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) as one of the layers on top of silk and entangling silk nanofibers layer in a TENG in single-electrode mode and demonstrated a flexible fiber-substrated TENG (F-TENG) (Fig. 11b)162. This F-TENG was fabricated using a combination of electrospinning and electrospray techniques, resulting in a unique layered microstructure. Notably, this design aimed at user comfort with reliable electrical output, making the F-TENG suitable for activities like typing, writing, or general skin contact162, which is one of the ideal wearable electronic applications. In a more recent work, a highly efficient, wearable, water-resistant, and fully recyclable TENG consisting of composite PEO/silk nanofibers film as tribo-positive layer and poly(vinyl butyral-co-vinyl alcohol-co-vinyl acetate) nanofibers (PVBVA-NFs) film as tribo-negative layer was developed with large output voltage of 2.1 kV by Joshi and Kim163. They demonstrated this TENG can act as motion sensor, producing different voltage patterns for various human activities and have potential in HMI applications.

a Textile-based wearable hybrid triboelectric-piezoelectric nanogenerator (TPNG), consisting of PVDF nanofiber and PEO/silk nanofiber layers, integrated with a micro-cantilever to perform in integration mode for real-time fall detection, enabling a remote emergency call microsystem. Reprinted with permission161. Copyright 2018, Elsevier Ltd. b Flexible fiber-substrated TENG (F-TENG) in single-electrode mode, consisting of mixed silk nanofiber/carbon nanotube layer on top of entangling silk nanofiber layer, for energy harvesting from daily activities such as typing, writing, or skin contact. Reprinted with permission162. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. c Water-resistant and fully recyclable TENG consisting of composite polyethylene oxide-silk nanofibers (PEO-Silk-NFs) film as tribo-positive layer against poly(vinyl butyral-co-vinyl alcohol-co-vinyl acetate) nanofibers (PVBVA-NFs) film showing sensing capabilities: different voltage waveform obtained when used in various parts of body acting as motion sensor and self-powered tactile sensor arrays (SPTSA) for gesture recognition and tactile sensing via sensor arrays to be used in HMI. Reprinted with permission163. Copyright 2024, Elsevier B.V.

Polylactic acid, polycaprolactone, and polyethylene oxide

Biodegradable polymers of polylactic acid (PLA), polycaprolactone (PCL), and polyethylene oxide (PEO), have emerged as attractive materials for many applications due to their biocompatibility and degradability164. They can be efficiently used in TENG devices in various forms, such as in PEO matrix165,166 or biodegradable polymer nanofibers167. Electrospinning allows these polymers to be processed into nanofibers for diverse enhanced functionalities in healthcare and environmental protection168. Recently, there has been important advances in TENGs consisting of these biodegradable electro-spun nanofibers169. Here we provide most recent representative work on PLA, PCL, and PEO-based electro-spun nanofibers with respect to wearable TENGs in contact-separation mode for some specific applications.

For air filtering applications based on PLA, it has been shown that composite electro-spun PLA/MOF nanofibers170 can have better performance than commercial ones, while PLA melt-blown nonwovens were efficient for PM0.3 removal171. Furthermore, Song et al. prepared a highly electroactive PLA-based nanofibrous membranes (NFMs) as positive electrode integrated with a TENG-based on CNT electrode as negative electrode, and developed a recharging mechanism as a self-powered respirator. This design enabled prolonged respiratory protection against fine and ultrafine particulate matters (PM0.3 and PM2.5), while offering wireless monitoring of physiological parameters, highlighting the potential of TENG in wearable healthcare applications (Fig. 12a)172. A more recent work from the same group demonstrated humidity-resistant TENG face mask with improved interface polarizability of PLA-based nanofibers and they tested their device by machine learning-based respiratory monitoring173.

a Self-powered respirator utilizing highly electroactive PLA nanofibrous membranes (NFMs) for respiratory protection, real-time physiological monitoring, and wireless communication. Reprinted with permission172. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. b Self-powered, single-electrode TENG-based flexible tactile sensor array and HMI for real-time monitoring of pressure distribution within prosthetic sockets, fabricated using biocompatible PDMS film, PCL nanofiber membranes, and PEDOT: PSS electrode. Reprinted with permission174. Copyright 2023, Elsevier Ltd. c A wearable TENG for human motion monitoring and energy harvesting, consisting of sodium chloride (NaCl) into electro-spun PEO nanofibers as tribo-positive layer against MXene doped PVDF-HFP layer. Reprinted with permission175. Copyright 2024, Elsevier Ltd.

Meanwhile, PCL and PEO nanofibers have taken important role in motion sensing applications. Chang et al. used the fact that PCL has high specific surface area and introduced a self-powered, single-electrode mode TENG-based flexible tactile sensor array for prosthetic sockets as HMI174. This sensor system utilized an all-biocompatible tribo-layers PDMS and PCL nanofiber membranes, with PEDOT:PSS as electrode, enabling real-time monitoring of internal pressure distribution (Fig. 12b)174. Faruk et al. constructed a self-powered TENG in contact-separation mode, made of V2CTX MXene doped PVDF-HFP composite nanofiber (VPCN) mat and tribo-positive layer of PEO nanofiber layer, labeled as VPCN-TENG175. MXene increased the electronegativity, while formation of micro-capacitor networks in PVDF-HFP enhanced the dielectric property. Most importantly, highly hydrophilic, and semi-crystalline PEO nanofibers played a crucial role in accurate voltage outputs in human body motion monitoring.

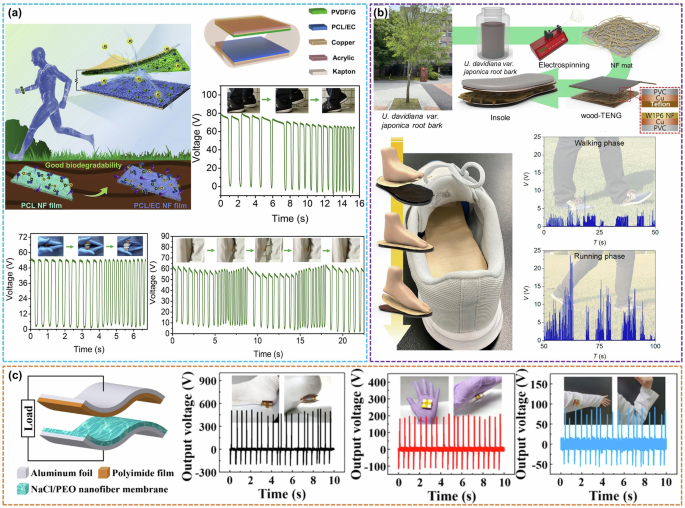

Recently, outcome of making composites and/or hybrids in PLA, PCL, and PEO nanofibers and using them in wearable TENGs was also brilliant. Among these, PCL-based nanofibers-based ones have been noticeable in motion sensing. Fan et al. reported a wearable TENG based on PVDF/graphene composite nanofibers film layer against tribo-positive layer of PCL/ethyl cellulose (EC) biocomposite nanofibers film with remarkable performance compared to pure PCL nanofiber film (46 times enhanced output voltage), with highly polarizability (due to EC), mechanically strength (due to PCL), and good biodegradability (Fig. 13a)176. That flexible TENG was attached to the human body as a wearable motion sensor and was possible to obtain stable, accurate intensity at varying frequency to a variety of human activities176. In another PCL nanofibers study, Park et al.177 demonstrated mechanically durable, superhydrophilic, and sustainable wood-derived triboelectric nanogenerator (wood-TENG) with relatively larger energy harvesting compared to existing conventional biodegradable TENG counterparts (3 to 10 times) mainly due to high surface area. It also exhibited antifungal activity and mechanical robustness, allowing to be used in shoe sole (Fig. 13b). The wood-TENG was composed of a wood-derived natural product doped PCL nanofiber mat (labeled as W1P6, with specific concentration of wood product) as tribo-positive layer against a Teflon tape, and able to distinguish walking from running. Another pioneering study of wearable TENG was conducted in hybrid PEO-based nanofibers by Lee et al.178. They introduced a method for integrating sodium chloride (NaCl) into PEO nanofibers to vary dielectric constant. This careful tailoring of charge carrier density together with dielectric constant resulted in enhanced power generation and 3.3 times larger output voltage compared to pristine PEO nanofibers. Therefore, more efficient (in addition to being renewable) pressure sensors and mechanical energy harvester from human body motions were possible (Fig. 13c)178.

a An energy harvester and human motion detector utilizing a contact-separation TENG consisting of tribo-positive layer of composite ethyl cellulose doped poly-ε-caprolactone nanofiber (PCL/EC) layer against graphene doped PVDF (PVDF/G) nanofiber layer, with outstanding output (46 times enhanced output voltage compare to pristine PCL) and stable, accurate intensity and frequency response to various human activities. Reprinted with permission176. Copyright 2022, The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. b Self-powered TENG-based flexible tactile sensor array for real-time monitoring of pressure distribution within prosthetic sockets, fabricated using biocompatible PDMS and PCL nanofiber membranes. Reprinted with permission177. Copyright 2022, Elsevier Ltd. c A TENG for pressure sensing and energy harvesting from human body motions, constructed through integration of sodium chloride (NaCl) into electro-spun PEO nanofibers used against polyamide film yielding 3.3 larger output compared to pristine PEO nanofibers. Reprinted with permission178. Copyright 2023, American Chemical Society.

Conclusions and perspectives

A concise overview of the burgeoning field of electro-spun nanofibers integration into smart, flexible wearable electronics via nanogenerators (involving mainly triboelectricity-based nanogenerators, i.e., TENGs) was provided. Various TENG systems with varying electro-spun nanofiber materials were introduced from main wearable electronic aspects, such as wearable sensing, human-machine interfaces, self-powered systems, and amplified energy harvesting. The electro-spun nanofibers mentioned here can be summarized in terms of electroactivity (tribo-negative or tribo-positive), water resistance, mechanical strength, TENG mode, and specific application. But, also, they can be classified as being exclusively composite or not. Nature of the nanofibers being pristine, composite, or hybrid could have decisive role179 in wearable TENG performance and applications. Because, composites consist of materials, which are cooperating but not necessarily exhibiting mixed effects at nanoscale, unlike hybrid materials, which can show novel effects, such as in the case of hybrid organic-inorganic perovskites180. Tables 1 and 2 give a synopsis and comparison of most prominent examples regarding electro-spun nanofibers used as components of wearable TENGs in this survey: (1) exclusively composite and (2) other forms (pristine, hybrid, and hybrid/composite), respectively.