Emerging trends in SERS-based veterinary drug detection: multifunctional substrates and intelligent data approaches

Introduction

Food safety concerns have intensified regarding veterinary drug residues in agricultural products, particularly in livestock and aquaculture. Despite strict regulations, illicit and excessive use of veterinary drugs—ranging from antibiotics to growth promoters—continues to pose significant health risks1,2.

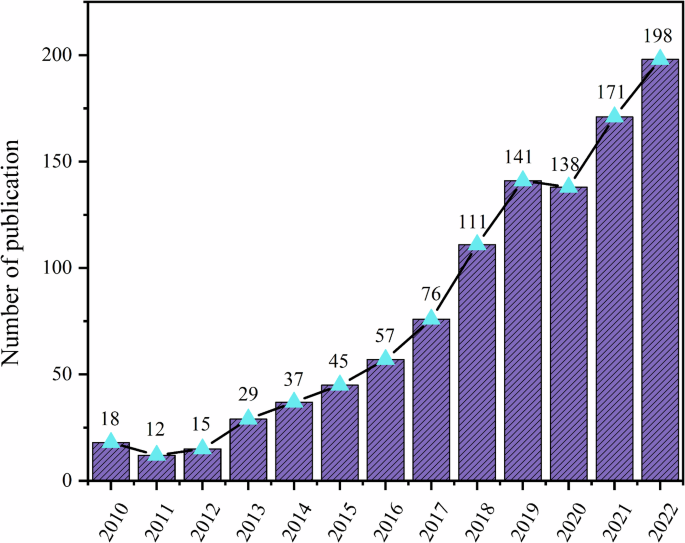

Although traditional analytical methods have high accuracy, they are limited by the complexity of detection pretreatment and long detection time, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography(HPLC), Gas Chromatography(GC), Capillary Electrophoresis(CE), Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry(LC/MS), and Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)3. SERS has gradually become a promising detection method with advantages in sensitivity, response time, and compound recognition specificity. The growing adoption of SERS in veterinary drug residue detection is evidenced by the significant increase in related publications from 2010 to 2022 (Fig. 1).

Number of publications in Web of Science related to SERS detection of residues from 2010 to 2022.

However, detecting veterinary drug residues based on SERS faces two main challenges. First, the design and synthesis of substrates must accommodate diverse sample matrices while maintaining high sensitivity and specificity, which is crucial because various types of food or animal products, such as meat or dairy, have different compositions and structures that can influence the Raman signal. Sensitivity refers to the ability of the substrate to detect even trace amounts of drug residues or other target substances, while specificity refers to the substrate’s ability to identify the target substance without interference from irrelevant compounds selectively. Therefore, it is essential to design and manufacture SERS substrates that can efficiently detect target substances, minimize interference from complex sample components, and maintain high sensitivity and specificity. The reproducibility problem of SERS substrates necessitates more stable and reliable designs to ensure consistent performance across various sample types4.

Second, the analysis of complex biological substrates generates large volumes of data that require advanced processing techniques. These challenges have spurred the development of smart, multifunctional substrates and cutting-edge analytical methods. The complexity of SERS data makes traditional data analysis methods insufficient, as SERS signals are not only influenced by the target molecules themselves but may also be interfered with by impurities, solvents, and surface contaminants. These impurities may hinder the adsorption of target molecules on the substrate, especially for molecules with weak affinity, thereby weakening their SERS signals. Alternatively, the SERS signals generated by the impurities themselves can overlap with or even overshadow the target signal. Furthermore, during SERS measurements, photothermal effects caused by localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effects, or photogenerated thermal carriers decomposition, may generate amorphous carbon signals, which create noise peaks that obscure the Raman signals of target molecules. LSPR is the resonant oscillation of free electrons on metal nanoparticle surfaces in response to light.

Due to these complex interferences, traditional data analysis methods, such as simple intensity-based quantitative detection, are difficult to effectively differentiate the target molecule’s signal5. To improve the accuracy of data analysis and signal-to-noise ratio, more advanced techniques are required, such as deep learning-based pattern recognition, denoising algorithms, and signal separation technologies. These methods can extract useful molecular information from noise and interference signals, thus enhancing the sensitivity and reliability of SERS detection6.

Deep learning, driven by advances in computing power and big data, presents promising solutions to these challenges. Its ability to automatically extract features from complex datasets, without requiring domain-specific expertise, makes it particularly well-suited for SERS applications7. The integration of deep learning with SERS has the potential to optimize substrate design, enhance spectral data processing, and significantly improve detection accuracy8.

The enhancement effect of SERS signals is non-linear with respect to factors such as laser intensity, the size and shape of metal nanoparticles, and localized electric fields9. The strength of the SERS signal is not only dependent on the intensity of the laser but is also closely related to the strength of the local electric field on the metal surface. This enhancement effect is largely induced by SPR, especially when molecules near the metal surface interact with the laser. Therefore, SERS signals exhibit complex non-linear behavior, such as fluctuations by several orders of magnitude due to factors like laser power, particle spacing, and molecular diffusion.

Deep learning can handle the non-linear enhancement effects in SERS10. Traditional SERS data analysis methods, such as linear regression-based signal analysis or simple peak fitting, are inadequate for capturing the non-linear characteristics of SERS signals11. Deep learning models, especially neural networks, can extract features from complex datasets through multi-level nonlinear mapping, without explicitly defining all the physical relationships12.

SERS signals often require processing a large amount of data, including experimental data under different conditions. Deep learning has a significant advantage in handling large-scale data, especially when the data volume is vast, the features are diverse, and the signal noise is strong. Deep learning can automatically extract key features from this data and identify meaningful patterns, without requiring extensive manual feature selection13.

Traditional peak fitting methods may fail to effectively distinguish the different components of complex signals, especially when signal interference is strong. Deep learning, however, can train on raw spectral data to identify subtle changes in the signal and accurately classify them. By training the network, the model can learn how to identify signal features related to target molecules without being interfered by impurity signals or noise14.

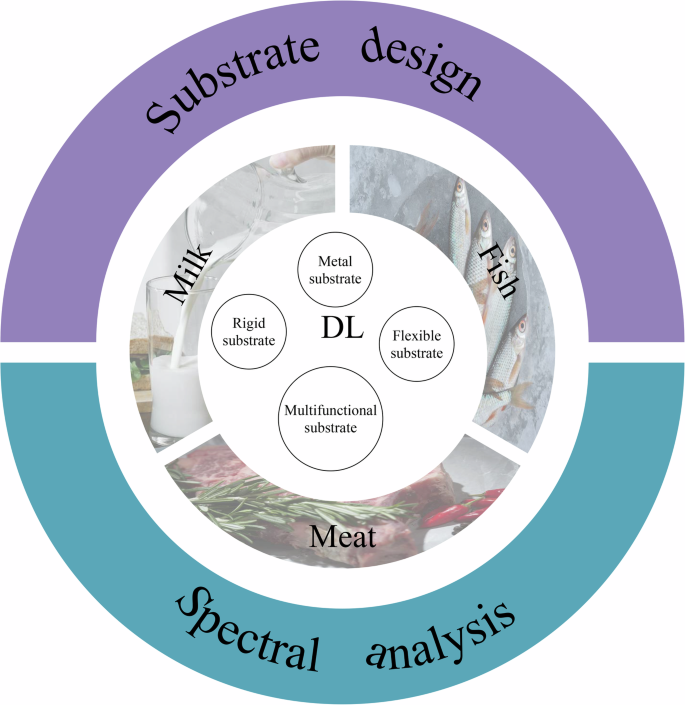

This review systematically addresses these challenges and potential solutions in SERS-based veterinary drug detection. First, the evolution of SERS substrates toward multifunctionality is examined, providing specific examples of their application in analyzing various animal-derived foods. Then, how deep learning enhances SERS applications through substrate synthesis optimization, data preprocessing, and model development is explored. The review concludes with a forward-looking perspective on the synergistic development of SERS and artificial intelligence in veterinary drug residue detection (Fig. 2).

Graphic showing a summary of the table of contents covered in this review.

Through this comprehensive analysis, we aim to provide insights into current limitations and innovative solutions in SERS-based veterinary drug detection, particularly focusing on the integration of smart substrate design and deep learning applications.

Surface enhanced raman scattering: principles, applications, and challenges

SERS principles and advantages

SERS began in 197415, rooted in Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman’s discovery of the Raman effect in 192816. SERS enhancements stem primarily from electromagnetic and chemical processes17,18,19. Since the mid-1970s, SERS has seen rapid development with a variety of substrates15, each having unique properties. Different types of SERS substrates have been identified, ranging from metal nanoparticles in suspension to those integrated with porous materials, and categorized based on their material, like ionic nanoparticles or organic semiconductors20,21,22,23. These advancements highlight the diverse applications and potential of SERS in molecular spectroscopy. Utilizing criteria from previous studies, we evaluate SERS substrates against several key indicators24,25,26,27. The indicators used to evaluate the substrates, such as those listed in Table 1.

Liu et al. categorized SERS substrates based on their advantages and application values, including flexible, reusable, selective for specific targets, and microfluidic SERS-based sensors28. Liu et al.’s Classification focuses on the relationship between the enhancement effect and particle shape, offering a simplified approach to selecting substrates based on structural features. While effective for identifying optimal shapes, this method may overlook other important factors, such as chemical properties, particle size, and distribution, which can also significantly impact SERS performance. Nguyen et al. classified trace analysis SERS substrates into four main types: spherical nanoparticle-based, non-spherical nanostructured, multi-particle composite nanostructured, and flexible substrates29. Nguyen et al.’s Classification organizes substrates by material type, which helps researchers select appropriate substrates based on specific enhancement effects or target recognition needs. However, it may not fully account for material compatibility with particular experimental environments, potentially limiting its practical applicability in some cases. In their study, Lin et al. described four distinct SERS substrate types, differentiated by design approach: (1) metal nanoparticles (MNPs) in suspension, (2) metals deposited on solid matrices, (3) metals integrated with porous materials, and (4) MNPs applied to biological or commercial bases30. Lin et al.’s Classification emphasizes functionality, making it particularly useful for applications such as biosensors or environmental monitoring. However, the complexity of categorizing based on functionality can lead to overlapping categories and difficulties in establishing unified evaluation criteria, potentially complicating the classification process. Azadeh Nilghaz et al. classified SERS substrates into three categories based on substrate material: ionic nanoparticles, and inorganic and organic semiconductors31. Azadeh Nilghaz et al.’s Classification is based on surface modification and functionalization, which can enhance SERS performance through tailored adjustments. While this approach is highly adaptable for various applications, the increased complexity in preparation and reliance on surface modifications may limit its scalability and reproducibility.

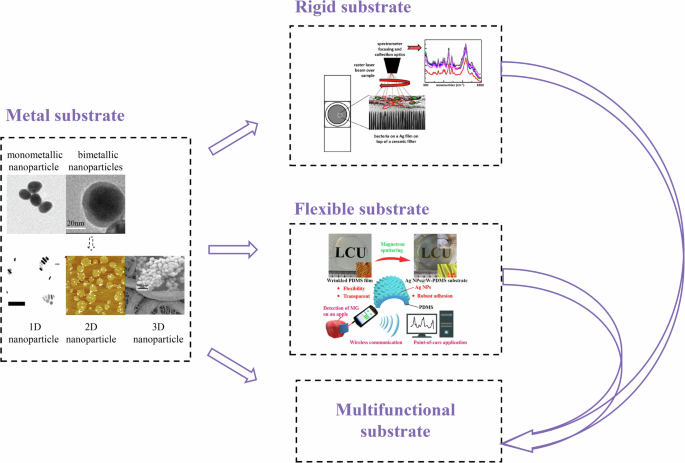

In contrast to these methods, our classification system integrates multiple dimensions, including the development timeline, the different forms of substrates, the diverse application scenarios, and the detection requirements, offering a more comprehensive and versatile approach. This paper, taking into account the developmental phases of SERS, methodologies of preparation, application objectives, performance criteria, and the materials and structures employed, identifies four principal types of SERS substrates: (1) Metal-based substrates, (2) Rigid substrates, (3) Flexible substrates, (4) Multifunctional substrates. Metallic substrates are the earliest types and have been the focus of research for a long time. Rigid and flexible substrates are products that have emerged from metallic substrates due to different application needs. However, with the development of SERS technology, these types of substrates can no longer fully cover the diversity of substrate needs, so in this paper, we propose a new type of substrate — multifunctional substrates. A detailed discussion of this can be found in “Development of SERS Substrates”.

Our classification method offers a scientific, systematic, and targeted framework for selecting the best SERS substrate based on the needs of different application stages, providing high matching and practicality across various stages of technological development. Additionally, by incorporating factors from materials science, nanotechnology, application needs, and performance optimization, this interdisciplinary approach enhances the comprehensiveness and foresight of the classification, offering unique strategic guidance for the long-term development of SERS technology. Figure 3 illustrates the basic development trajectory as discussed in this review.

The basic development process outlined in this review41,69,236,237,238,239.

Development of SERS Substrates

Metal substrates

Metal substrate is the most important module in SERS substrate. In essence, many other substrates are derived from the research and development of metal substrate. Therefore, we focus on the metal substrate to highlight its central role in SERS technology. In metal substrate, 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D structures represent different dimensional configurations of nanomaterials, each with distinct properties and applications. 0D nanostructures are nanoparticles confined in all three spatial dimensions, typically spherical, offering high surface-to-volume ratios and quantum effects, which are useful for sensing and catalytic applications. 1D nanostructures, like nanowires or nanotubes, have two nanoscale dimensions and a larger third dimension, enhancing electromagnetic fields and providing localized hotspots that significantly boost Raman signals in SERS applications. 2D nanostructures are thin, flat materials such as nanoparticle arrays or graphene, where one dimension is on the nanoscale, and the other two are larger. These structures are ideal for creating ordered arrays that maximize hotspot density, improving SERS signal enhancement. Finally, 3D nanostructures extend in all three dimensions, providing the highest surface area and hotspot density, which significantly improves SERS sensitivity and signal intensity. The expanded surface area and increased hotspots in 3D structures allow for more effective use of the Raman lasers’ confocal volume, enhancing SERS’s detection capabilities. Each dimensional structure offers unique advantages for various applications, particularly in enhancing Raman spectroscopy for more sensitive and accurate detection (Hotspots in SERS refer to localized regions on metal nanoparticle surfaces where the electromagnetic field is intensely amplified, significantly enhancing the Raman signal for more sensitive molecular detection).

0D metal substrates are the earliest type of SERS substrates and serve as the foundation for all related research. They have laid the crucial theoretical and experimental groundwork for the development of subsequent substrates. 0D nanoparticle structures include both mono-metallic and bi-metallic nanoparticles32. These nanoparticles are often synthesized on assembled or roughened surfaces and gained prominence in the 1980s33. Common materials for 0D nanoparticles include Au, Ag, Cu, Si, and carbon-based materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and fullerenes. Among these, Au/AgNPs is the most widely used in SERS due to their excellent optical properties, ease of synthesis, and high surface reactivity. The size, shape, and dielectric function of metal nanoparticles affect the LSPR, thereby determining the effectiveness of Signal Enhancement. For example, in the study, size-adjustable AuNPs were used to regulate clenbuterol in pork34, and size-adjustable AgNPs were employed to detect salbutamol in pork35.

Single metal nanoparticles, particularly Au and Ag, often exhibit suboptimal performance in SERS due to limitations such as weaker LSPR in Au and aggregation issues in Ag36. As a result, bimetallic nanoparticles, which combine the high stability of Au with the superior plasmonic properties of Ag, were developed to enhance SERS performance by optimizing both the structural stability and plasmonic resonance properties. These bimetallic structures include alloys and core-shell structures, with their SERS performance dependent on the proportion and distribution of the metals37. Some researchers have already used adjustable Au@Ag NPs to detect ractopamine in pork38.

Recent studies have expanded beyond Au-Ag alloys to include metal-zinc oxide and metal oxide-metal nano SERS substrates39. For example, the AuNPs/PSi hybrid structure was used to enhance the rapid detection of penicillin in spiked milk40. These substrates exhibit exceptional performance and a wide range of applications due to hotspot generation or charge transfer. Compared to regular spherical nanoparticles, anisotropic particles generate stronger hotspots, significantly enhancing EFSERS. Hence, the development of 1D, 2D, and 3D metal structures is gradually emerging.

1D structure, where two dimensions are significantly smaller than 100 nanometers while the third dimension is comparatively larger, is considered ideal SERS substrates. This is due to their enhanced local electromagnetic fields and tunable LSPR properties41,42,43,44,45. Common 1D model structures include single nanowires46, nanoparticle nanowire assemblies47, nanowire dimers48, and nanowire bundles49. For example, AgNPs can form nano-chains under the influence of CTAB and MUA through self-assembly50. Additionally, vanadate nanorods (β-AgVO3 NRs) have been used for ultrasensitive detection of chloramphenicol in milk51.

Unlike 0D and 1D structures, which are mainly particles or linear arrangements, 2D structures involve flat or nearly flat arrangements of nanoparticles or nanostructures. These can range from ordered nanoparticle arrays to thin films with specific geometric patterns.

Common types of 2D nanostructures include nanoparticle arrays, metal films, and graphene-based materials. Nanoparticle arrays are highly ordered structures that maximize hotspot density, while metal films, such as those made from Au, Ag, or copper, can also produce strong plasmonic resonances when structured on substrates. Additionally, 2D materials like graphene and transition metal dichalcogenides are being explored for their unique electronic properties, which can enhance SERS signals in specific wavelength ranges. In this context, Au NFs@ZIF-67 has been used to detect histamine in fish to estimate the freshness of fish products52.

Beyond traditional metal nanoparticle arrays, SERS substrates based on two-dimensional materials, such as graphene53, hexagonal boron nitride54, Black Phosphorus (BP)55, SnSe256, MoS257, WS258, AuNPs/2D MoS259. These materials combine the advantages of 2D nanostructures, such as high surface area and unique electronic properties, offering new directions for SERS applications.

Researchers also have explored various synthesis methods to prepare precious metal SERS substrates of different dimensions, such as star-shaped60,61, linear62, rod-shaped63,64, polyhedral65, and cubic structures66, thus leading to the derivation of 2D and 3D nanostructures. Compared to disordered metal nanoparticle films, the enhancement factor of 2D periodic arrays can be several orders of magnitude higher, primarily attributed to reduced losses such as hysteresis or damping effects.

3D structures more effectively utilize the confocal volume of Raman lasers67. 3D nanostructures, significantly extended in the z-axis direction68, greatly enhance SERS signals with an increased number of hotspots and expanded surface area, offering possibilities for more accurate and sensitive detection69,70.

The synthesis of 3D nanostructures is often more complex than that of 1D or 2D structures. Common fabrication methods include bottom-up approaches like self-assembly, chemical vapor deposition, or templating techniques. These methods allow for the creation of intricate and well-defined 3D shapes, such as nanoparticle clusters, dendritic structures, and interconnected networks. Such structures can also be tailored to exhibit specific plasmonic properties, such as tunable LSPR, by adjusting the size, shape, and material composition of the nanoparticles.

The design and fabrication of 3D SERS substrates exploit three dimensional space for superior performance. Various materials have been explored for making these substrates, including precious metals71, semiconductor materials72, graphene family materials73, polymer materials74, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)75. The integration of these materials enhances the multifunctionality of the substrates, such as having a large specific surface area, selective adsorption, rapid enrichment capabilities, and synergistic electromagnetic and chemical enhancement effects.

Some of the most common 3D nanostructures used for SERS applications include Au or Ag nanoparticle aggregates, hierarchical nanostructures, and nanofoam structures76. For example, the use of Ag or Au nanoparticle clusters can create 3D networks with extremely high surface areas, which enhance the formation of hotspots. Similarly, dendritic or branched nanostructures are highly effective at creating localized regions of intense electromagnetic fields. These 3D designs are not only capable of producing strong SERS signals but also offer the potential for long-range plasmonic interactions that can further improve the detection sensitivity over larger areas. The main categories of 3D SERS substrates include multilayer substrates, microporous substrates, and array substrates. While these substrates exhibit significant advantages, important research topics in practical applications include further enhancing their SERS performance, simplifying the fabrication process, and improving stability. For example, lamellar nanostars, sea urchin-shaped nanostars, and serrated nanostars have been used to detect crystal violet in fish77.

There are diverse strategies for manufacturing 3D SERS substrates, typically including assembly strategies78, bottom-up approaches79, template-assisted strategies80, and other integrative strategies81. The fabrication process might be relatively complex, like integrating 3D laser lithography with assembly methods and combining template-assisted methods with assembly techniques82. These comprehensive strategies leverage their respective strengths to guide the development of high-performance 3D SERS substrates.

Under normal circumstances, from 0D to 3D nanostructures, there is an obvious performance improvement, accompanied by the increase of costs and manufacturing complexity. While 0D nanoparticles have the lowest enhancement factors and poor uniformity, they are widely used due to their low cost and simple synthesis process. 1D nanostructures show improved performance with better uniformity, though at increased cost. 2D nanostructures represent a major leap in performance, demonstrating excellent uniformity and reproducibility at moderate costs, making them an optimal balance between performance and cost. 3D nanostructures achieve the highest enhancement factors and sensitivity, making them ideal for ultra-sensitive detection, though their complex production process leads to the highest costs and relatively poorer uniformity and reproducibility. This dimensional progression reflects the inherent trade-off between performance enhancement versus cost and manufacturing complexity.

In terms of performance, 3D nanostructures offer the highest enhancement effect, but they also come with the highest fabrication complexity and cost. On the other hand, 0D nanoparticles are the cheapest but provide the weakest enhancement. 1D and 2D nanostructures strike a better balance between performance and cost, with 2D nanostructures particularly excelling in uniformity, stability, and sensitivity. Overall, 0D and 1D structures are suitable for general detection needs, while 2D and 3D nanostructures stand out in high-performance, ultra-sensitive detection applications.

Metal substrates, due to their nanoscale size, are well-suited for integration with enzymes, antibodies, probes, and other biomolecules for veterinary drug detection, making them the most widely used in this application.

Rigid substrates

Uncontrollable aggregation of colloids associated with metals poses significant challenges in terms of stability and repeatability in practical applications83,84,85. These challenges have led to increasing attention on solid matrix-supported SERS substrates.

Rigid substrates, developed more recently in the early 2000s, offered a stable and reproducible solution by providing a structured surface for metal films that could enhance electromagnetic hotspots in a controlled manner. Rigid substrates are typically composed of a layer of metal film rich in electromagnetic hotspots laid on a hard substrate86. Some rigid substrates can be directly synthesized, such as the uniformly fixed AgNPs (AAO/Ag) on a waffle-like anodized aluminum, which is carefully designed and manufactured as a SERS substrate for the rapid determination of chloramphenicol in honey87.Plasma treatment was used to prepare large-area uniform nanoforest structures on a PMMA substrate, and a high-sensitivity Ag/PMMA SERS substrate was obtained via thermal evaporation. This substrate successfully detected melamine in milk at a concentration of 0.001 ppm, well below the allowed level of melamine in milk88

Methods for preparing such orderly hard substrates mainly divide into top-down60,89,90 bottom-up91,92,93, and templating approaches89,94,95. Top-down methods can precisely control the microstructure and dimensions of the substrate, providing highly ordered and structurally uniform SERS-active substrates. However, they have limitations, such as the inability to assemble structures with nanogaps smaller than 5 nm, and they require expensive equipment with high costs and significant time consumption86. Bottom-up methods involve assembling small nanostructure units into ordered nanostructure arrays. Compared to top-down methods, these are simpler to operate, less costly, and suitable for large-scale batch production, but they struggle to precisely control the shape, distribution, and density of the assembled nanostructures. The uniformity and batch repeatability of the substrates prepared by these methods still need further optimization. Templating methods involve depositing nanostructures directly onto hard templates (like glass, quartz, silicon, etc.), providing well-organized superstructures and nanogaps, and creating highly enhanced plasmonic regions88. In some cases, AgNPs are directly synthesized and added onto metal plates to modify TiO2 nanotube arrays. These have been successfully used as integrated SPME-SERS substrates for extracting and identifying antibiotic degradation products in real milk samples96.

With technological advancements, rigid substrates have been applied in commercial detections, such as detecting harmful compounds in food safety and environmental monitoring. Commercial solid surface substrates, like Klarite and Q-SERS, have been used for detecting melamine97,98, malachite green99, and pesticide residues on the surfaces of fruits and vegetables100. Homemade solid surface substrates, like Au-coated zinc oxide composite nanoarrays101, have also shown great potential.

Despite these substrates offering higher stability and customizability, they still face challenges. High cost is a major issue, especially for commercial solid surface substrates used in food analysis. Additionally, due to their lack of flexibility, these substrates cannot adhere to irregular surfaces, limiting the possibilities for in-situ surface Raman analysis102,103,104,105. When using these substrates, detecting solid samples with non-flat surfaces requires complex preprocessing, thus limiting the applications of non-invasive detection106.

Flexible substrates

Flexible substrates have emerged as a promising alternative to traditional rigid substrates due to their ability to adapt to irregular and non-planar surfaces, which are common in practical sample analysis107. Traditional rigid substrates, such as silicon, glass, and aluminum foil, require complex sample pretreatment steps, like dissolving target analytes in solvents and adsorbing them onto plasmonic templates for analysis108. These rigid substrates also struggle to perform SERS on rough or curved surfaces, limiting their practical application in real-world scenarios. In contrast, flexible SERS substrates can be easily applied to various unconventional surfaces, such as the curved or irregular surfaces of objects, enabling more versatile and non-destructive testing109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116.

The design principles of flexible SERS substrates are similar to their rigid counterparts, with a core requirement of high average enhancement factors. These factors largely depend on the type of plasmonic metal used, the size and shape of the nanostructures, and the assembly method of these nanostructures. Flexible substrates can be categorized into four types based on the construction method of the plasmonic structures: in-situ wet chemical synthesis, physical deposition of plasmonic metals, nanoparticle adsorption, and nanoparticle embedding108,117,118,119.

The advantages of flexible SERS substrates are significant. Beyond sensitive detection akin to rigid substrates, they facilitate unique non-invasive analyses. These substrates can be cut into any desired shape and size, easily wiped or wrapped around sample surfaces, enabling non-destructive and even in-situ detection120. Additionally, lightweight flexible SERS substrates can be integrated with portable Raman devices for on-site testing121,122.

For example, the implementation of flexible substrates, specifically thin cotton fabric functionalized with plasmonic nanoparticles, demonstrates superior conformability to non-planar surfaces, facilitating in-situ detection of pesticide residues on intact fruit surfaces. This methodology circumvents the necessity for sample manipulation or destruction. In contrast, conventional rigid substrates, such as glass slides, exhibit inherent limitations in surface contact when interfacing with curved geometries, thereby compromising measurement accuracy unless significant sample modification is performed. For example, Ag/nanocellulose fiber SERS substrates (Ag@NCF substrates) have been used to detect compounds like furanonitrile, thiabendazole, malachite green, and enrofloxacin in fish123.Additionally, special types of flexible materials, such as using polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) plasma chambers as SERS substrates, have been employed to detect tetracycline in milk124.

Besides traditional materials like metals and plastics, flexible substrates now include cotton fabrics, tapes, and biological materials. These materials, with their unique structures and properties, such as the 3D interconnected framework of cotton fabrics125, the adhesive nature of tapes126, and the natural homogenous 3D nanostructures of biological materials, are utilized in constructing SERS substrates. Biologically-derived materials successfully used in SERS substrate preparation include rose petals127, cicada wings128, dragonfly wings129, eggshell membranes130, and mantis wings131. Common flexible SERS substrates also encompass cellulose132 polymers, and graphene-based substrates133. Cotton fiber-Ag composites are suitable as SERS substrates for detecting malachite green (MG) residues in fish134.

In the field of flexible SERS, three main technological categories prevail135 Firstly, ‘actively tunable SERS’, where the platform’s performance can be adjusted to meet various detection needs, demonstrating versatility across applications. Secondly, ‘swab sampling SERS strategies’, utilizing flexible materials like swabs to directly collect samples from various surfaces for analysis, are well-suited for rapid on-site testing. Lastly, ‘in-situ SERS detection methods’, allow analysis at the sample’s original location, reducing the complexity of sample handling, and providing more accurate molecular information.

Flexible SERS substrates still face challenges in industrial applications. The utilization of natural materials such as rose petals as flexible SERS substrates presents intrinsic challenges related to autofluorescence phenomena. In the absence of appropriate fluorescence-quenching treatments, the intrinsic fluorescence emission from these biological substrates can significantly interfere with the target analyte’s Raman spectral features. This spectral interference potentially leads to compromised detection sensitivity and unreliable analytical results, particularly in trace-level molecular detection applications. A significant challenge is the presence of competing molecules in complex matrices, potentially affecting the accuracy of quantitative detection. Designing specific recognition elements, antibodies, or molecular imprints could enhance substrate specificity. Moreover, issues like fluorescence interference, cross-contamination, and analyte saturation adsorption need addressing. Most flexible substrates are disposable, and finding renewable approaches will be a focus of future research.

Multifunctional substrates

In the field of SERS, metal substrates, rigid substrates, and flexible substrates each have their distinct characteristics and limitations. The common goal for these types is to achieve enhanced, stable, and uniform signals, along with improved cost-effectiveness and repeatability. To address these challenges, researchers are striving to improve the shortcomings of each substrate type. For instance, metal substrates are being explored with more economical metal or non-metal materials, such as semiconductors and MOFs, to enhance their capabilities. Semiconductors are categorized into inorganic, organic, and hybrid conductors.

The above three kinds of substrates have their advantages and disadvantages. For example, the synthesis method of metal substrate is simple, but it has low repeatability and high price. Although the rigid substrates have been developed to the commercial level, there are few application scenarios. The flexible substrates overcome the above shortcomings, but synthesis is more troublesome.

With the emergence of an increasing variety of novel substrates, existing substrate classification methods can no longer fully encompass all types of substrates. Some of the older classification methods may be overly simplified and fail to meet current needs. For example, new substrate types, such as DNA hydrogel networks generated by ligation-rolling circle amplification (RCA), are used for simple and ultrasensitive detection of kanamycin (KANA). In the presence of KANA, the double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) structure of the aptamer is disrupted, and the released primers are used to construct two partially complementary circular lock probes (CPPs). The DNA hydrogel network is formed by the winding and self-assembly of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) chains generated by two RCAs, during which AuNPs (GCNPs) and magnetic beads (MBs) are entangled and incorporated. Finally, quantitative detection of KANA is successfully achieved using the DNA hydrogel network136.Although this substrate can be categorized as a flexible substrate because it belongs to the hydrogel type, its functions and applications have exceeded the traditional concept of flexible substrates, presenting a new direction for development. Additionally, special types of flexible materials, such as PDMS plasma chambers used as SERS substrates for detecting tetracycline in milk, have moved beyond the traditional concept of flexible substrates124.

A trend in SERS substrate development is the integration of multiple functions into a single substrate. This allows for the detection of minute quantities of analyte molecules adsorbed on the enhanced surface but also makes SERS particularly sensitive to surface contamination. Therefore, SERS substrates are often used for single measurements to ensure optimal sensitivity and quantitative accuracy, significantly increasing the cost of SERS analysis. Considering the cost and environmental impact, designing recyclable and highly sensitive SERS substrates has become a research hotspot. In the development of reusable and regenerable integrated SERS substrates, a key focus is on repeatability and regeneration. This includes simple substrate recycling procedures137, designing photocatalytically regenerable substrates138, superhydrophobic self-cleaning designs139, and strategies involving reversible intermolecular interactions140. In addition, using digital (nano)colloid-enhanced Raman spectroscopy, reproducible quantification of a broad range of target molecules at very low concentrations can be routinely achieved with single-molecule counting, limited only by the Poisson noise of the measurement process141.

In self-cleaning substrates, they contain plasmonic precious metals that provide SERS enhancement and photocatalytically active materials capable of degrading adsorbed analyte molecules. For example, multifunctional FeO@TiO@Ag microparticles have been designed as recyclable SERS substrates for direct antigen detection in human serum. Concentrating the microparticles using an external magnetic field can further enhance their catalytic efficiency. Using human serum containing antigens as a test sample, adsorbed antigens can be degraded to undetectable levels after a certain period of ultraviolet light exposure, allowing the microparticles to be reused.

While photocatalytically regenerable SERS substrates allow for the effective removal of even strongly adsorbed analytes, these procedures often require careful operation by experts, limiting their routine application. Visible-light-induced self-cleaning SERS substrates may be more sustainable and typically offer faster regeneration speeds. For instance, actively reduced graphene oxide (RGO)@MoS@Ag nanopowders have been designed, which can be regenerated using sunlight exposure. These nanocomposites exhibit excellent SERS efficiency and demonstrate superior photocatalytic activity.

In addition, superhydrophobic self-cleaning enhanced substrates can often be rapidly regenerated through simple water rinsing. These substrates typically comprise dispersed precious metal nanoparticles on microstructured surfaces, mimicking the surface structures of self-cleaning biological materials. For instance, a non-pin type superhydrophobic film with plasmonic layered micro and nano surface structures has been designed as a reusable SERS substrate. This substrate can be regenerated through simple water washing, while its special surface structure allows for significant enrichment of the analytes.

Reusable SERS substrates constructed via reversible intermolecular interactions are usually achieved by functionalizing the enhanced surfaces with functional material layers. For example, a reusable SERS sensor has been designed for real-time monitoring of CO based on the reversible interaction of CO with iron porphyrin. This sensor can be regenerated through simple environmental adjustments, allowing multiple CO detection cycles. Alternatively, self-calibrating SERS substrates have been developed, some of which have been combined with the functional materials discussed above to construct integrated separation-calibration-enhancement SERS substrates. These substrates allow direct quantitative SERS analysis of complex samples with higher precision and accuracy. Self-calibrating enhanced substrates are mainly divided into two categories: surface modification via adsorption of self-assembled monolayers and calibration using inherent reference substances142.

Using self-assembled monolayers of Raman reporter molecules to modify the enhanced surface is a common strategy to introduce self-calibration functionality. For instance, Raman reporter molecules like 4-Mercaptobenzoic acid and 5,5’-Dithiobis strongly adsorb on Ag/Au surfaces, producing intense Raman scattering. These reporter molecules can serve as internal standards, improving the quantitative performance of SERS.

Calibration using inherent reference substances involves cases where SERS/Raman signals can be directly used as stable references for signal calibration. For example, the SERS signal of acetone in Au nanoparticle arrays has been used as a reliable reference for calibrating analyte molecules. This method does not rely on surface modification of the enhancement materials, allowing analyte molecules to approach and interact directly with the enhanced surface.

To address the challenges of analyzing actual samples, including the chemical and physical complexity of sample matrices such as proteins and DNA in meat, researchers have developed multifunctional SERS substrates that can directly separate and enhance the target analyte signals from complex matrices. These are mainly categorized into (1) magnetic and wetting-based separation; (2) polarity-based separation; (3) intermolecular interaction-based separation; (4) size exclusion-based separation143,144,145.

Magnetic SERS substrates can be dispersed in sample solutions and conveniently extracted using a magnetic field. For example, mixtures of magnetic nanoparticles and plasmonic precious metal nanoparticles have been used for direct analysis of physically challenging samples like honey. Another approach involves using superhydrophobic SERS substrates to directly separate heterogeneous mixtures of water and oil for independent analysis. Intermolecular interaction-based separation is achieved by functionalizing the surface of enhanced nanomaterials with functional material layers, allowing the separation of compounds in complex sample matrices. For instance, enhanced surfaces modified with aptamer or antibody self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) can selectively capture target analytes. Size exclusion-based separation uses nanoporous materials like zeolites or polymer macromolecules to repel large molecular contaminants from the enhanced surface, enabling direct SERS analysis of biological samples.

It is noteworthy that substrate design must consider other critical metrics, such as suitability for automated batch production and stability during storage. More importantly, standardized procedures and methods must be developed to determine substrate performance, as well as the practical application of SERS, as these are key prerequisites for promoting SERS to non-specialist users146,147.

Metal-based substrates typically offer high selectivity and excellent sensitivity due to their strong plasmonic properties, but they may lack uniformity and reproducibility across large areas, and their cost can be relatively high. Rigid substrates provide good stability and reproducibility, but they may have limited flexibility and can be more challenging to scale for varied applications. Flexible substrates are advantageous for their versatility, cost-effectiveness, and ease of use in diverse sample environments, though they may sacrifice some uniformity and stability compared to rigid substrates. Multifunctional substrates combine multiple properties, offering high selectivity and potential for enhanced performance, but they often face challenges in maintaining uniformity, reproducibility, and cost efficiency, depending on the complexity of their design and materials.

Examples and challenges of SERS applications in veterinary drug residue detection in animal-origin food products

The detection of veterinary drug residues in animal-origin foods is crucial for food safety and regulatory compliance. SERS has gained popularity in this area due to its high sensitivity, rapid analysis, and minimal sample preparation. There are two main approaches to SERS-based detection: targeted and non-targeted detection.

Targeted detection focuses on identifying specific veterinary drug residues using selective probes or receptors. This method has the advantage of high sensitivity and can meet regulatory requirements, making it the most commonly used approach in veterinary drug residue detection. In targeted SERS detection, specific molecules are often employed to selectively bind to the drug residues, enabling precise detection at very low concentrations. However, targeted detection has limitations, particularly when identifying unknown or emerging veterinary drug residues. In such cases, label-free detection has been receiving increasing attention. Unlike targeted detection, label-free SERS detects a wide range of substances by analyzing the overall Raman scattering signal of the sample, including unknown veterinary drug residues. While label-free detection offers a broader detection scope, it typically has lower sensitivity compared to targeted methods and requires more complex data analysis techniques. Non-targeted SERS detection has been applied in high-throughput screening scenarios, where these methods can rapidly scan a large number of samples, making them crucial in preliminary screening processes. In the study, the screening of crystal violet residues in pond water, Au/Ag bimetallic nanocuboid superlattices coated with Ti3C2 nanosheets were used as the substrate148. This represents a non- targeted detection approach.

Despite the advantages, both targeted detection and non-targeted detection faces challenges, including lower sensitivity and increased complexity in data analysis. To improve the performance of both targeted and non-targeted detection, advances in SERS substrates are essential. Most current SERS-based veterinary drug detection techniques use metal-based substrates, such as AuNPs and Ag NPs, which are cost-effective and relatively simple to synthesize. However, complex matrices like food samples can interfere with the Raman signal, requiring the development of effective spectral preprocessing techniques to improve the quality of the data.

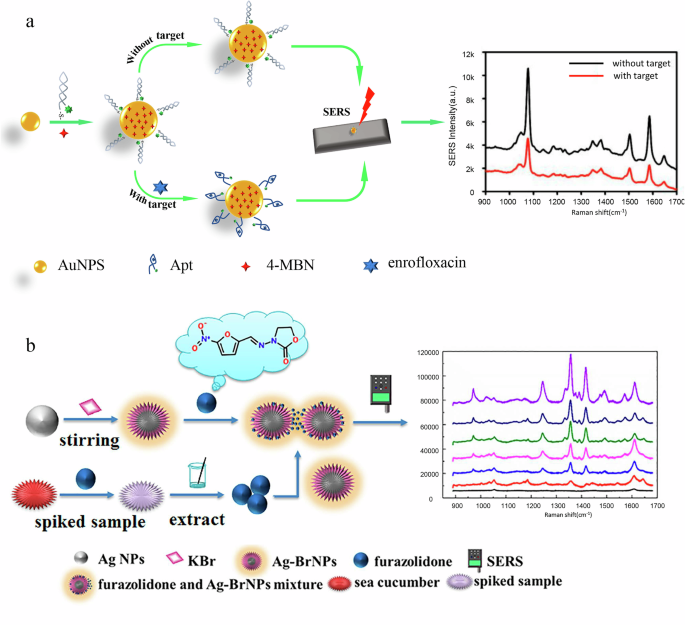

There is usually a direct correlation between tagging methods and target detection. Target detection usually involves the use of tagging methods, as tagging can improve sensitivity, especially at very low concentrations of the target substance. Labeled SERS detection involves tagging the drug residue with a fluorescent or radioactive marker. This marker then enhances the Raman signal, allowing for more sensitive detection. For example, labeled SERS detection has been applied in the detection of clenbuterol in pork149, and enrofloxacin in fish and chicken150. In the detection of clenbuterol in pork, researchers used an aptamer probe combined with Fe3O4@Au@Ag as the substrate, achieving a detection limit as low as 0.003 ng/mL. Similarly, aptamer-based detection with AuNPs has also been applied to detect enrofloxacin in fish and chicken. These methods demonstrate high sensitivity and specificity, enabling accurate differentiation of various veterinary drug residues. However, this method requires additional steps for tagging the drugs, which can be time-consuming and may lead to potential interference in complex samples.

Label-free SERS detection can directly measures the Raman signal from the drug residue without the need for external markers. This method has the advantage of being simpler, as it avoids the time-consuming labeling process and reduces the possibility of interference, making it more suitable for rapid analysis in real-world applications. For example, label-free targeted SERS detection has been successfully applied to detect amprolium HCl in chicken and duck151. Similarly, label-free detection has been used for the detection of quinolone and flunixin meglumine in pork152. In these studies, researchers employed Au@AgNPs as substrates for detecting amprolium HCl in chicken and duck, achieving a detection limit of 0.48 nmol/L. For quinolone and flunixin meglumine in pork, AgNPs and Au@MIL-100(Fe) were used as substrates, with detection limits of 1 μg/L and 0.15 mg/g, respectively. Figure 4 shows a schematic diagram illustrating both labeled150and label-free detection methods153.

a labeled detections; b label-free detection.

It is noteworthy that, as summarized in Table 2, the current veterinary drug detection predominantly uses metal-based substrates, encompassing 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D nanostructures, with limited use of rigid substrates and flexible substrates. As mentioned above, metal substrate is still the simplest substrate to synthesize, which is one of the reasons why metal substrate has the most application scenarios and is still under study. In addition, most application scenarios need to measure the samples several times. Therefore, for most veterinary drug residue detection scenarios, the simplicity and cost of substrate synthesis methods must be considered in the future multifunctional substrate.

Regarding the comparison of detection limits between SERS and conventional platforms, SERS generally offers superior sensitivity compared to traditional methods. Conventional platforms, such as LC-MS and ELISA, while highly accurate and reliable, typically have higher detection limits and require more complex sample preparation154. In contrast, SERS can detect substances at concentrations as low as ppb levels, often without the need for markers, making it more sensitive and convenient for rapid testing.

In some veterinary drug detection cases, the detection limits have not met the required standards, often due to the use of relatively simple substrate types. Many studies use metal-based substrates because they are easy to synthesize and cost-effective. However, in certain complex samples, these substrates may not perform well. For example, when using AuNPs as a substrate to detect florfenicol residues in chicken meat, the detection limit was 0.25 μg/L, which did not meet the required standards155. Moreover, the detection limit in veterinary drug testing is influenced not only by the type of substrate used but also by various factors such as laser power, aggregating agents, sample preparation, measurement time, temperature, and matrix interference. In other veterinary drug detection cases, the detection limits have already met national standards. For example, using a three-dimensional nanoporous Au substrate for detecting malachite green isothiocyanate in fish meat, the detection limit can reach 10−16 M156, which is due to the high Enhanced Raman Scattering effect of the 3D Au-based substrate. This allows for a lower detection limit, meeting the regulatory requirements. Therefore, SERS shows significant advantages in many fields, especially in the detection of veterinary drug residues and environmental monitoring.

Moreover, several issues have been identified in the detection of veterinary drugs. As mentioned, the Raman effect, being a weak phenomenon, is easily contaminated by noise and other corrupting factors157. For instance, the complex matrix of milk, especially the high protein content, can interfere with the SERS signal, which underscores the importance of preprocessing steps158. Spectral preprocessing, including background noise removal, smoothing, and signal enhancement, is crucial for improving the quality and readability of SERS spectra159. According to studies by Bocclitz et al. and Guo et al., spectral normalization and dimension reduction are always necessary after obtaining raw spectra, peak correction, wavenumber calibration, intensity calibration, baseline correction, and spectral smoothing160. Due to the high computational complexity of the above preprocessing sequence and the lack of universal preprocessing techniques, over-processing can lead to data distortion161. Additionally, the absence of standardized preprocessing protocols across different laboratories and instruments means that some methods may be inappropriate.

Research progress of SERS combined with deep learning for veterinary drug detection

Foundations and chanllengs of deep learning veterinary drug detection in SERS

Despite these challenges metioned in “Examples and Challenges of SERS Applications in Veterinary Drug Residue Detection in Animal-Origin Food Products”, traditional methods such as linear models struggle to capture the complexity of SERS data13. Linear models, while simple and easy to use, are not capable of accurately reflecting the true relationship between SERS signals and analyte concentration, particularly in complex sample matrices. This is because SERS signal intensity is influenced not only by the analyte concentration but also by factors like substrate uniformity, sample preparation methods, and experimental conditions. Over-reliance on these simplistic models often leads to misinterpretation of results. Furthermore, data analysis with traditional techniques faces additional challenges, such as baseline/background drift, low signal-to-noise ratio, peak shift, peak broadening/narrowing, and strong peak overlap162. These issues complicate the extraction of meaningful quantitative data from the raw SERS spectra.

This is where deep learning becomes indispensable. Traditional approaches fail to effectively handle the vast amounts of high-dimensional data generated by SERS, especially when dealing with complex samples163. Deep learning techniques can process large-scale datasets and automatically identify complex patterns, offering a significant advantage over conventional methods164. These algorithms can handle issues like noise, baseline drift, and peak distortion, while improving signal-to-noise ratios and resolving overlapping peaks165. Moreover, deep learning models are capable of identifying subtle correlations between SERS signals and analyte concentrations that traditional models may miss. In addition, the design and optimization of SERS substrates, which plays a critical role in signal enhancement and sensitivity, is another area where deep learning proves valuable166. By predicting the performance of different substrate configurations and materials, deep learning can guide the development of substrates that maximize sensitivity and specificity for veterinary drug residue detection167. Deep learning are capable of identifying subtle correlations between SERS signals and analyte concentrations that traditional models may miss168. By integrating deep learning with SERS, it becomes possible to not only address the limitations of conventional data analysis but also enhance the accuracy169, sensitivity, and reliability of veterinary drug residue detection, making it feasible for real-world applications in complex environments170.

Overall, the application of SERS technology in the detection of veterinary drug residues in animal-origin foods shows great potential. However, the complexity of signal preprocessing and limitations in quantitative analysis remind us that data must be handled cautiously in practical applications, and more advanced data processing and analysis methods, such as deep learning, should be considered to enhance accuracy and robustness171. The power of deep learning in large-scale, high-dimensional data processing and complex pattern recognition offers a promising solution to the challenges posed by traditional methods in SERS-based detection172.

Deep learning enables sophisticated tasks that require implicit knowledge and high-dimensional data interpretation, which are often difficult for humans to perform. It has demonstrated superhuman abilities in specific, controlled environments, such as image classification and strategy-based games, exemplifying its vast potential and adaptability in fields beyond human capability173. The core advantage of deep learning lies in its ability to autonomously derive hierarchical feature representations from complex data structures, achieving progressively abstract levels of insight through multi-layered networks174. This allows algorithms to extract nuanced patterns and representations from data, facilitating comprehensive analysis across various domains175. Deep learning’s architecture is commonly composed of stacked layers where lower levels capture fundamental features, which higher layers abstract into more complex patterns176.

In practical applications, deep learning has shown groundbreaking success across fields such as speech recognition177,178,179,180,181, computer vision182, and natural language processing183,184,185. Within these domains, its unique strengths and capabilities continually reshape technological boundaries, proving its adaptability and potential for innovation.The evolution of deep learning has yielded a variety of specialized network architectures, each tailored to different data structures and analytical needs. These include: Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) for general-purpose learning tasks186, Autoencoders(AE) and VAE for feature learning and dimensionality reduction187, Recurrent Neural Networks (RNN) for temporal and sequential data are widely used in applications like natural language and time-series analysis188,189,190, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) foundational in image processing due to their capability to capture spatial hierarchies191, Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) and Conditional GANs (CGANs), known for generating new data samples192, U-NET for image segmentation tasks, crucial in medical imaging193, Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithms194,Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) for graph-based data, such as social or molecular networks195, Densely connected convolutional networks(DENSENET)196.

Advanced deep learning techniques for optimizing SERS in veterinary drug residue detection

Deep learning technology has shown immense potential in predicting and understanding specific SERS nanostructures and molecular properties, marking a forward-looking research direction in the field197. Researchers are actively exploring deep learning to optimize the design of substrates and molecules, as well as to identify the best manufacturing conditions, thus achieving the desired performance characteristics198. This approach has significantly improved the efficiency of the design process199. With the aid of deep learning, preprocessing methods have also undergone substantial enhancements, facilitating processes such as pattern recognition, differential detection, correlation analysis, and prediction of results and potential factors. This, in turn, has enhanced the quality of data in subsequent analyses200. Table 3 summarizes the current role of deep learning in key areas: SERS substrate design and spectral analysis. Specifically, in the paper, substrate design includes both structural design and optical property prediction, while spectral analysis is broken down into spectral preprocessing and both qualitative and quantitative analysis of spectra.

In the initial step of veterinary drug residue detection, traditional substrate design relies on empirical methods and intuitive physical understanding, such as utilizing Maxwell’s equations and Mie scattering theory to predict the scattering characteristics of spherical nanoparticles201. However, the combination of CNN and RNN offers a new pathway for SERS substrate design. These methods approximate the equations by learning the complex relationships between input structures and output properties, rather than directly solving Maxwell’s equations. For instance, the U-Net architecture modified by Li et al. mapped scattering and incident images onto electromagnetic wave scattering nanostructures with various shapes, orientations, material parameters, and illumination conditions202. Wiecha et al.’s trained 3D CNN predicted near-field and far-field responses203 while the CNN combined with the RNN model developed by Sajedian et al. showed potential in covering arbitrary structures with various thicknesses204. A key advantage of deep learning methods in SERS substrate design is their ability to handle highly complex structures while significantly reducing time and computational resource demands205. By learning from extensive datasets, these methods can rapidly and accurately predict the optical responses of nanostructures206. For example, training deep learning models to identify Raman spectral features of different nanostructures enables predictions to be made within seconds, supporting both forward and inverse design205,207. Importantly, these novel design methods are universally applicable across various domains, including veterinary drug detection.

Beyond substrate design, obtaining high-quality signals is crucial in SERS analysis. Advanced instruments and deep learning algorithms have been developed, focusing on improving the speed, resolution, and sensitivity of data collection and preprocessing while minimizing noise and background interference. Data preprocessing involves identifying and addressing defects in instruments and samples, such as spikes, background signals, and noise. Given the characteristics of these unwanted components—such as their frequency, bandwidth, and amplitude—appropriate strategies must be formulated for effective remediation. Some software allows for the manual removal of spikes caused by cosmic rays; however, this repetitive operation limits the potential use of other tools208. Consequently, CNNs in deep learning have been introduced to automate the extraction of cosmic ray features, minimizing manual intervention. Through supervised learning, CNNs can restore processed spectra using transposed convolution layers, matching the size and intensity of the input spectra, thereby significantly improving the performance of spike removal, irrespective of whether the spikes are close to or overlap with the Raman peaks5,12.

To address the challenge of limited SERS spectral data, data augmentation techniques increase diversity and scale by modifying existing data or generating synthetic data using deep learning. Common transformation methods include baseline variation, spectral line shifting along the horizontal axis, adding Gaussian noise, and linear superposition. These techniques have been applied in various SERS-based applications, such as the identification of milk types. For example, Kazemzadeh et al. reported a case where data augmentation significantly improved classification accuracy209. However, Houston et al. considered mixing Raman spectra from different categories, finding that it had a negligible impact on compound identification and could even reduce model performance210. Additionally, generative models like VAE have been employed to synthesize new data by approximating the distribution of data space. Data generated by VAE positively impacted deep networks, although it could negatively affect traditional machine learning models. Similarly, GANs have proven effective for synthesizing Raman spectra.

Even preprocessing methods leverage ANN to simulate different perturbation patterns for designing desired transmission matrices, thus facilitating the automatic design of modern multimodal optical elements. Diederich et al. optimized the shape of the illumination source for the target object’s structure, effectively enhancing phase and overall contrast211 Beyond original data collection, advances in microscope technology have introduced new encoding techniques based on the geometric characteristics of photonic nanostructures for information storage. By employing far-field characterization and CNNs in deep learning for optical retrieval, a 9-bit information storage capacity per diffraction-limited area has been achieved, significantly surpassing the traditional 1-bit capability5.

In label-free detection using SERS technology, any peak in the spectrum may represent an overlay of fingerprint spectra produced by the vibrational modes of multiple molecules. The intensity and frequency of these peaks can be influenced by substrate conditions and coexisting molecules. Therefore, manual calculation methods relying on a single or a few peaks may not suffice to uncover molecular characteristics, particularly in the complex context of veterinary drug detection.

As illustrated in Table 3, deep learning plays a significant role in veterinary drug detection of both qualitative and quantitative analyses, including: identifying specific molecular fingerprints within the spectrum212, determining the abundance of molecular concentrations213, analyzing multiple variations across the entire spectrum214, and resolving the spatial distribution of SERS features215.

Quantitative analysis can provide proportional values among different components, yielding deeper insights into molecular compositions. For instance, Au nanoparticle-modified violet phosphorene (VP) substrates demonstrated excellent reproducibility and a low detection limit for sulfamethoxazole, while a 1-D CNN-based deep learning model achieved 100% accuracy in distinguishing similar antibiotics174. Additionally, a sensor combining triple SERS signal amplification with machine learning successfully detected amoxicillin (AMO) and ciprofloxacin (CIP) in meat, with a high prediction accuracy (98.06%)216. Another study focused on a portable TLC-SERS sensor for detecting ofloxacin in beef, achieving a remarkable sensitivity of 0.01 ppm, and providing superior accuracy compared to traditional models217. Finally, a new deep learning model, HGASNet, was proposed to address issues like noise and spectral shifts in SERS detection of ractopamine in pork, demonstrating outstanding performance with R² = 0.997214. These studies highlight the potential of combining deep learning and SERS in enhancing the sensitivity and accuracy of veterinary drug detection, paving the way for safer food products.

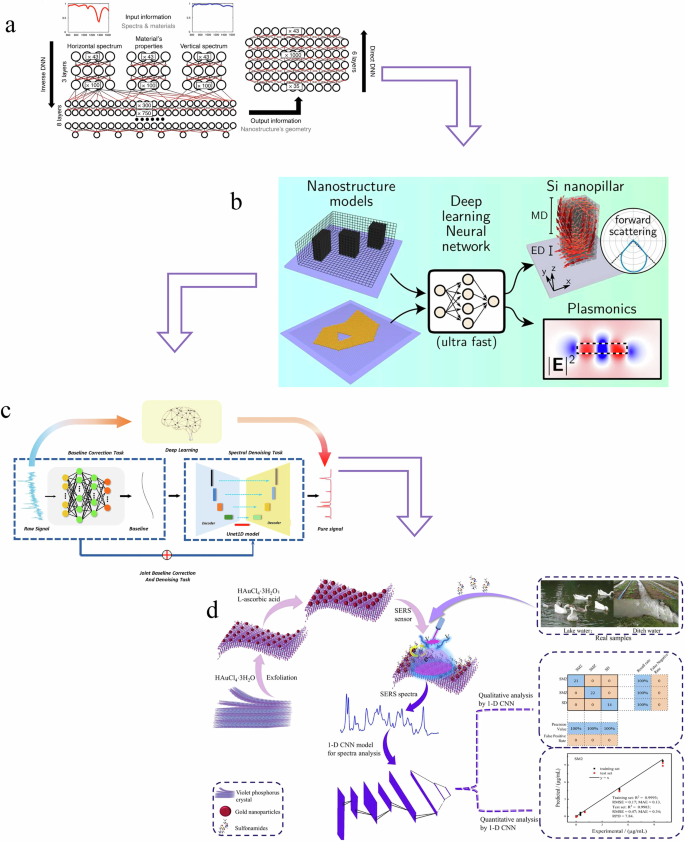

Moreover, deep learning’s ability to recognize and interpret complex patterns in spectral data is crucial for analyzing multiple changes and imaging throughout the entire spectrum. In veterinary drug detection, deep learning can help differentiate subtle differences between various drug components, even when traditional analysis methods struggle to discern these distinctions. Figure 5 illustrates several applications of deep learning combined with SERS in veterinary drug detection, including substrate design, optical property prediction, spectral preprocessing, and spectral analysis. These aspects highlight how deep learning enhances the performance and accuracy of SERS in detecting veterinary drugs. However, progress in this specific area remains limited at present.

a Structural design235; (b) Optical properties prediction233; (c) Spectral preprocessing10; (d) spectral quantitative/qualitative analysis240.

Challenges and future trends in the use of deep learning combined with SERS for veterinary drug detection

Challenges in applying deep learning to SERS for veterinary drug detection

The integration of SERS and deep learning in veterinary drug residue detection holds great promise but also faces several significant challenges. These challenges encompass various aspects, including the selection and design of reporter molecules for veterinary drugs, the representation of structurally similar drug molecules, generalization across different meat matrices, substrate costs in large-scale applications, issues with false samples, data imbalance, and the high demand for computational resources, among others.

Firstly, in the selection and design of reporter molecules for veterinary drugs, the interaction mechanisms between different types of veterinary drug molecules (such as antibiotics and hormones) and SERS substrates varys218. This requires the careful selection or design of appropriate reporter molecules for each type of veterinary drug. Reporter molecules play a crucial role in the accuracy of detection, covering three key stages in the detection process. For example, fluorescent molecules exhibit unique advantages in specific systems due to their resonance electromagnetic enhancement effect with SERS substrates219. Traditional methods may struggle with handling these effects, but recent studies show that deep learning models can analyze various characteristics of fluorescent molecules, such as their absorption and emission wavelengths in different solvents. This ability demonstrates the significant potential of deep learning in predicting molecular behavior and optimizing molecular selection. However, these deep learning models often rely on high-quality training data, which is difficult to obtain for fluorescent molecules suitable for veterinary drug residue detection. Therefore, the selection and optimization of molecules remain a challenge220,221.

Another major challenge is the development of effective representations for structurally similar veterinary drug molecules. Unlike SERS substrates, molecules may have structurally similar forms but different functions. As such, the representation of molecules must be both concise and unique, capturing key features such as atom types, bond lengths, three-dimensional conformations, and nuclear charges222. This requires researchers to strike a balance between the precision and diversity of molecular representations, avoiding excessive simplification that could result in the loss of important information.

Additionally, due to differences in the composition and structure of various meats (e.g., pork, beef, chicken), the same veterinary drug produces significantly different SERS signals in each type of meat. This matrix effect makes it challenging for models to generalize well and requires a large volume of training data across different matrix environments. Matrix interference also increases the difficulty of feature extraction, as the model needs to accurately identify the target drug’s features from complex mixed signals. To accommodate this complexity, model structures must become more intricate, which brings new issues such as an increased risk of overfitting and greater training difficulty. These challenges seriously impact the reliability and accuracy of deep learning models in practical detection applications.

Furthermore, challenges such as high substrate costs, false samples, and data imbalance are also present in veterinary drug residue detection. While small-scale data collection and experimental operations are feasible, as demand increases, the high cost and precision requirements of substrates make their application more complex. Deep learning-driven SERS technology requires large amounts of high-quality data, which places higher demands on the development and production of substrates, thus increasing costs and limiting its widespread application in large-scale experiments. Moreover, although automation and standardization in experiments can reduce human error, slight differences in sample collection, preparation, and measurement processes can still lead to false samples. These false samples affect the quality of the dataset, further impacting model training and performance. Finally, in veterinary drug residue detection, some drugs have extremely low residual concentrations and low detection frequencies, resulting in severely imbalanced datasets with an uneven ratio of positive and negative samples. This imbalance causes the model to bias towards the majority class during training, affecting its accuracy and detection performance.

Additionally, the demand for computational resources is a significant challenge in SERS applications. To enable the simultaneous detection of multiple veterinary drugs, the model needs to process massive amounts of spectral data. Training complex deep learning models, optimizing nanostructures, and improving spectral data quality often require powerful computational resources. For instance, developing high-resolution models to capture subtle variations in spectral data or simulating nanoscale structures typically requires substantial computing power, which is not only costly but also potentially burdensome to the environment. To overcome this computational limitation, high-performance computing, cloud computing resources, and hardware accelerators (such as GPUs and TPUs) will become essential. Furthermore, optimization algorithms need to be developed to reduce the model’s complexity without sacrificing accuracy, making AI-driven SERS applications more scalable and accessible223,224.

Future trends in the integration of deep learning with SERS for veterinary drug detection

The future development of deep learning combined with SERS for veterinary drug detection will follow several key trends. As deep learning technologies advance, intelligent molecular design and optimization will become crucial. Machine learning can predict interactions between molecules and SERS substrates, enabling the development of more efficient detection methods with higher sensitivity and selectivity. This approach can significantly reduce the cost and time of traditional trial-and-error experiments. Additionally, to address interference from different meat matrices, future models will focus on adaptive mechanisms that automatically adjust for variations in signal caused by different matrix environments, leading to more stable and reliable detection.

In data processing and model optimization, future detection systems will integrate data from various methods, including SERS spectra, mass spectrometry, and chromatography, to improve accuracy and reliability through multimodal data fusion. To address high computational resource demands, the focus will be on developing lightweight models, using techniques such as model compression and knowledge distillation to maintain performance while reducing computational complexity225,226. Furthermore, to overcome challenges in data acquisition, transfer learning and few-shot learning will be increasingly applied to help models perform well with limited training data.

Current challenges, such as dataset quality, model generalizability, and interpretability, point toward several future research directions. Building high-quality, representative datasets and developing deep learning models that balance interpretability with predictive power are pivotal steps forward. Additionally, multimodal data fusion, along with the automation and standardization of experimental procedures, could reduce variability in data collection and preprocessing, thereby enhancing reproducibility in veterinary drug detection applications227,228,229.

In particular, the limited availability of veterinary drug residue samples has posed a challenge for traditional deep learning algorithms, which generally rely on large datasets for robust training. Approaches such as small-sample learning, data migration, and GAN provide solutions by generating synthetic data to augment the dataset or adapt models to work effectively with fewer samples230. These methods have demonstrated success in SERS-based applications, where GANs have been used to generate realistic synthetic spectra, increasing dataset diversity and model robustness.

The interpretability of deep learning models remains a crucial requirement in scientific applications, especially in fields like SERS where physical principles play a central role. A deeper understanding of deep learning models’ internal mechanisms—often described as ‘black boxes’—could yield insights into the relationships between nanostructures’ optical properties, geometric shapes, and material attributes201. Techniques for analyzing the decision-making processes within models allow researchers to establish stronger connections between substrate design choices and SERS outcomes, ultimately supporting more scientifically grounded substrate optimization.

Deep learning models based on GAN architectures are already facilitating the generation of nanostructures with specific optical properties. By incorporating sequential architectures into the GAN’s generator, researchers have achieved stable convergence, even though the inverse solutions generated may lack uniqueness. This approach allows for greater flexibility in designing nanostructures that meet specific optical criteria231. Further work on interpretability-focused model designs will likely advance understanding in SERS applications, enabling more transparent and scientifically driven model predictions.

The intellectualization and automation of experimental system is also an important development direction. The future detection system will combine robot technology and artificial intelligence to realize the automation of the whole process of sample preparation, data collection and result analysis, improve data quality. At the same time, with the improvement of algorithm and hardware, the detection system will pay more attention to real-time, and can complete the detection quickly and give early warning in time, which is of great significance to food safety supervision and quality control.These trends will collectively accelerate the application of SERS technology in veterinary drug detection, particularly for complex matrices and multi-component detection, where deep learning will play an increasingly important role.

Conclusion

This article provides an in-depth overview of recent advancements in SERS technology for veterinary drug residue detection, emphasizing the evolution of substrate designs and potential future multifunctional forms. By examining specific detection cases, it highlights current challenges and innovative strategies for advancing detection accuracy and reliability. The integration of deep learning enhances SERS by substrate structure design optimization, optical property prediction, spectral preprocessing, and both qualitative and quantitative spectral analyses, all of which contribute to higher sensitivity and selectivity. However, challenges such as generalization across different meat matrices, substrate reproducibility, high material costs, and the computational demands of deep learning models remain obstacles to wider application. Addressing these issues through scalable, cost-effective manufacturing, AI-driven predictive modeling, and optimized computational strategies will be crucial. Looking forward, as technological and methodological innovations continue, SERS technology is expected to deliver faster, more precise, and accessible solutions for veterinary drug residue detection.

Responses