Emoji-mediated comments in Chinese vlogs: pragmatic and rhetorical perspectives

Introduction

In 1982, Professor Scott Fahlman (USA) used punctuation marks to form a rotated smiley face [:-)] to distinguish nonserious conversations from serious conversations. This practice was gradually expanded to include a set of expressions in the United States. Later, the Japanese adjusted Fahlman’s rotated face to a similar frontal expression, [^_^], and called it [顔文字] kaomoji, which conveyed the affective states and emotions by developing physical organs such as the eyes, mouth, and nose through punctuation, letters, Chinese characters and Japanese kana. In the late 1990s, Shigetaka Kurita from Japan created [絵文字]emoji, which is now mainly built into IOS and Android and is widely seen on social media, expressing emotions by highlighting facial expressions and indications of objects. For example, the [ ]emoji was voted as the word of the year in 2014 and a billion times of usage daily, and the [

]emoji was voted as the word of the year in 2014 and a billion times of usage daily, and the [ ]emoji was chosen as the word of 2015 by the Oxford Dictionary. Over the long course of emoticon development, six variants have been widely employed on social media: kaomoji, emoji, stickers, GIFs, images, and videos (Herring and Dainas, 2017). The latter four variants—which are sometimes accompanied by text—were mostly invented by individuals, while kaomoji and emoji were developed by software technology companies, with each emoticon having a unique code that is consistent across platforms. Kaomoji has notably fewer users because it is less consistently used than emojis and stickers, GIFs, images, and videos are in less consistent usage. The most stable, vivid, and expressive is the emoji (Herring and Dainas, 2017; Bai et al. 2019). Furthermore, statistics demonstrate that emojis enjoy an overwhelming frequency of 69% use compared with 12% use of emoticons (Jin et al. 2022). Therefore, emojis are also the focus of this study.

]emoji was chosen as the word of 2015 by the Oxford Dictionary. Over the long course of emoticon development, six variants have been widely employed on social media: kaomoji, emoji, stickers, GIFs, images, and videos (Herring and Dainas, 2017). The latter four variants—which are sometimes accompanied by text—were mostly invented by individuals, while kaomoji and emoji were developed by software technology companies, with each emoticon having a unique code that is consistent across platforms. Kaomoji has notably fewer users because it is less consistently used than emojis and stickers, GIFs, images, and videos are in less consistent usage. The most stable, vivid, and expressive is the emoji (Herring and Dainas, 2017; Bai et al. 2019). Furthermore, statistics demonstrate that emojis enjoy an overwhelming frequency of 69% use compared with 12% use of emoticons (Jin et al. 2022). Therefore, emojis are also the focus of this study.

To our knowledge, most existing emoji research focuses on daily conversations on Facebook (Dresner and Herring, 2010) or product promotion and marketing data on social media platforms such as Facebook and Weibo (Herring and Dainas, 2017; Ge and Gretzel, 2018). Vlogs seem to be absent from emoji studies in the current literature. However, vlogs, which are popular among individual users in documenting and promoting both domestically and internationally, have also been utilized by various cultural and tourism departments and authorities in China to promote their regions in recent years. Cultural and tourism vlogs are a new type of promotion, or more like a kind of organizational communication, which might differ from the communication and promotion on Facebook and Weibo. Emojis in vlog comments might perform the audience’s speech acts and provide feedback on the communication effect. However, the emojis in the vlogs comment section receive scarce attention and concern.

Therefore, the current study explores the role of emojis in the comments of Chinese regional promotional vlogs. The following section provides a brief overview of emoji research and key terms, thus introducing the research gap and questions of our study. The next section introduces the materials and methods. The next sections present emoji-mediated speech acts and the pragmatic functions of emojis in vlog comments. The penultimate section addresses the rhetorical identification achieved with the help of emojis in the vlogs comments. We present a discussion, conclusions, and limitations of this study in the last section.

An overview of emoji research

Before we present an overview of emoji research, we need to clarify a few key terms. First, according to Herring (1996), Kern et al. (2016), computer-mediated communication (CMC), which emerged in the 1960s and gained popularity in the 1990s, refers to communication that occurs between humans via the internet, the Web, mobile devices, converged media, and private intranets. CMC is available in various forms, such as instant messaging, emails, discussion forums, social media platforms, massive open online courses (MOOCs), and online distance learning (ODL) programs (Chew and Ng, 2021). CMC occurs in multiple dimensions, such as one-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, many-to-many, and even one alone (Nguyen, 2008), in educational, business, social, recreational, governmental, and other organizational contexts. There are two main types of computer-mediated communication: synchronous CMC and asynchronous CMC. Synchronous CMC refers to the interaction that occurs in real-time with an immediate exchange of messages. Common platforms for synchronous CMC include instant messaging applications such as WeChat, WhatsApp, Snapchat, and Facebook Messenger. Asynchronous CMC refers to interactions that are staggered over time, as people send and respond to messages at different times via email or posts on blogs or social media (Chew and Ng, 2021).

As previously mentioned, several types of emoticons exist. However, with its vivid image, rich information, and affective meaning, there is wide adoption of emojis in formal, informal and personal or business CMCs. There is currently no definition of emoji-mediated communication in the literature. In this study, emoji-mediated communication refers to communication realized through emojis alone or along with some verbal cues in CMC. The term “vlog” comes from “video blog” or “video log”. A vlog is simply a blog in which the medium is a video instead of written words. A vlog is most often a personal video that is filmed by the subjects themselves, with an introduction, procedures, or other information about specific interests being filmed and released regularly online. Vlogs, which emerged as personal sharing and display tools, were recently adopted by the Chinese Regional Culture and Tourism Department to share regional beauty. Unlike personal vlogs, vlogs released by culture and tourism departments are not released and uploaded daily or regularly. In fact, they resemble regional promotion and propaganda realized through the form of vlogs. Finally, David Crystal (2005) mentioned the definition of internet linguistics. He defined it as “synchronic analysis of language in all areas of internet activity, including email, the various kinds of chatroom and games interaction, instant messaging, and Web pages, and including associated areas of CMC, such as SMS messaging (texting)” (Crystal, 2005, p. 17). We believe that the language in vlogs is under the scope and study of Internet linguistics. In the next section, we present a brief introduction to current research on emojis.

With the founding of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism in China, the development of technology, the popularization of social media, and some disagreeable factors, such as COVID-19, in the past several years, some governmental cultural organizations, such as museums, attractions, and provincial departments of culture and tourism, have adopted vlogs to attract visitors both online and offline. For example, a vlog in which He Jiaolong, the secretary of the Department of Culture and Tourism of a remote region in China, played the leading role went viral in 2021 when the pandemic was still ongoing. Later, increasingly more leaders of the Department of Culture and Tourism acted in the vlogs to promote their regions, thus becoming web celebrities. The participation and involvement of leaders of the Department of Culture and Tourism encouraged the popularization of vlogs as popular media to promote regions in China. It was found that there were 2534 vlog accounts of culture and tourism nationwide up to 2024 (Li, 2024). Therefore, the tourism sector is a great arena where vlogs display their prowess for governmental tourism authorities. Moreover, data have revealed that there were more than 0.888 billion vlog users in China as of June 2021, accounting for 87.8% of internet users in China. It was reported that vlogs, following instant communication, have been the second most popular type of media (Huang, 2022). Among the vlog platforms, Douyin and Kuaishou attract the most users (Gao and Zhou, 2024).

With respect to emoji use in China, a survey showed that more than 90% of college students preferred emoticons in online communication (China Youth Net, 2021). Moreover, emojis have become an important form of nonverbal language in social media, according to the survey. The overwhelming preference for emojis in CMCs is a noteworthy characteristic of network language and culture. Ming Jing (2020) mentioned that an emoji is a visual picture used to identify emotions and release psychological stress in a social context. To a certain extent, colourful emojis cater to public psychology, trigger users’ emotional resonance under the domination of attention, and adapt to the growing number of netizens in the era of online media (Jing, 2020). Additionally, Jin et al. (2022) suggested that emojis fulfil social functions such as emotional expression, linguistic expression, interpersonal relationship maintenance, and language replacement in CMC. Bai et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of emojis in the following domains: computer science, communication, marketing, behavioural science, linguistics, psychology, medicine, and education.

As an indispensable part of CMC, emojis are special linguistic symbols that co-occur or even replace words. Liang (2006) elaborated on the origins of emojis in terms of Japanese cultural connotations and psychology, suggesting that emojis arose from the Japanese psychology of valuing frontal faces and visual information. Yu and Qin (2011) explored the essence of emojis, arguing that “text sequence+online emojis” in virtual communication is equivalent to “text sequence+facial expressions” in face-to-face communication and that the process of generating and understanding emojis is that of encoding and decoding language, which reflects the linguistic nature of emojis. Departing from the linguistic nature of emojis, scholars have carried out semiotic and linguistic research on emojis, mainly focusing on the semantic function of emojis (Barach et al. 2021), the pragmatic features of emojis or emojis (Dresner and Herring, 2010; Herring and Dainas, 2017; Ge and Herring, 2018; Togans et al. 2021), social-communicative functions (Yang and Liu, 2021; Ge-Stadnyk, 2021; Rodrigues et al. 2022; Cavalheiro et al. 2022), rhetorical functions (Ge and Gretzel, 2018), the emotional meaning of emojis (Jaeger et al. 2019; He et al. 2017) and comparisons of the pragmatic functions of emojis and other emoticons (Konrad et al. 2020). Therefore, emojis serve as emotional tools conveying affective states and attitudes and as paralinguistic tools to perform semantic, pragmatic, rhetorical, and communicative missions as verbal language does.

In previous linguistic research, emojis have been examined from pragmatic (Togans et al. 2021; Dresner and Herring, 2010; Herring and Dainas, 2017) and rhetorical (Ge and Gretzel, 2018) perspectives separately. Togans et al. (2021) explored emojis under the guidance of the politeness principle and face theory. Dresner and Herring (2010) conducted research on emoticons from the perspective of speech act theory. Their research revealed the contextually dependent illocutionary forces achieved through emoticons in daily computer-mediated interpersonal dialogues. The characteristic of the research lies in emoticons (including kaomoji and emoji) and interpersonal communication (i.e., communication between individuals). The emoticons in dialogues helped realize illocutionary speech acts and intentions between individuals. The illocutionary forces of emoticons revealed the pragmatic role of emoticons even as a paralinguistic element in CMC more than ten years ago. Herring and Dainas (2017) analysed the pragmatic functions of graphicons (including emoticons, emojis, stickers, GIFs, images, and videos) on Facebook. Six main functions emerged from their analysis: mention, reaction, tone modification, riffing, action, and narrative sequence. Dresner and Herring’s (2010) and Herring and Dainas’ (2017) research had common ground: these two studies explored graphicons in interpersonal communication in CMC from the pragmatic perspective, which revealed the pragmatic functions of graphicons in CMC. The study of graphicons in interpersonal communication raised doubts concerning emojis’ pragmatic role and illocutionary forces in the newly-emerging vlogs with the widespread usage of emojis in CMC.

Moreover, from a rhetorical perspective, Ge and Gretzel (2018) studied the rhetorical relationship between emojis and the context of social media. Ge and Herring (2018) observed how social media influencers adopt emojis to persuade and establish their credibility (ethos), touch others’ emotions (pathos), and articulate their logical reasons (logos). The former focused on emojis and textual language, and the latter focused on emojis as a persuasive strategy used by social media influencers to average internet users. Both of these studies focused on emojis on social media between individuals and ignored the examination of the effect of interpersonal communication (rhetoric of reception). To investigate the communicative effect of online communication, comments constitute a good channel. As a part of network language and internet linguistics (Crystal, 2005), Douyin comment language reveals the characteristics of network language, and it is timely to study Douyin comment language (Kou, 2020). Therefore, we collect network comment language as a study object to explore the speech acts and communication effectiveness of the comment language of tourism vlogs.

These observations of prior emoji research from pragmatic and rhetorical angles reveal that emojis in vlogs and emoji persuasion should be examined from a reception perspective. Moreover, the pragmatic intention and role attempting to achieve and play by emojis overlap with the persuasive effect or communication effectiveness in interpersonal communication. As an important paralinguistic element, every emoji might serve as a speech act independently or cooccur with texts, aiming at realizing a certain communication effect, i.e., rhetorical effect. Additionally, previous studies on emojis have employed either pragmatic or rhetorical perspectives (Togans et al. 2021; Herring and Dainas, 2017; Dresner and Herring, 2010; Ge and Gretzel, 2018; Ge and Herring, 2018).

As vlogs have become increasingly popular among internet users, official cultural and tourism departments of provinces and regions have filmed their own promotional vlogs to meet the increasing need for travel and to promote regions. As they are carefully filmed and beautifully presented, these promotional vlogs of regional spots of attraction receive much attention and many responses. However, there appears to be a real paucity of research addressing emojis from a combined pragmatic and rhetorical framework to observe the speech acts and communication effects of emojis. Thus, our research questions are as follows: (1) In the official communicative activity of regional culture and tourism promotional vlogs, what kind of speech acts do viewers perform with emojis in comments, and how are the speech acts distributed? (2) In the rhetorical activity of regional culture and tourism promotional vlogs, what kinds of responses do viewers make to vlogs by containing emojis in their comments? (3) How do emojis’ pragmatic speech acts and rhetorical responses organically integrate with comments to help viewers convey their attitudes towards vlogs?

In 1962, John Langshaw Austin’s How to Do Things with Words marked the founding of speech act theory; specifically, Austin argued that the object of language research should not be the words and sentences but the acts that were achieved through them. He distinguished between constatives and performatives. Austin’s distinction between constatives and performatives was a powerful attack on logical positivists, who claimed that “any statement that cannot be proved to be true or false is a pseudostatement and is meaningless”. Austin’s distinction between constatives and performatives was the immediate source of speech act theory. However, later, Austin realized that constatives were just as capable of performing a certain act as performatives and abandoned the division between constatives and performatives. Austin broke down the action performed in uttering performatives into three kinds of actions: locutionary act (mere utterance of the performative, consisting of phatic, phonetic and rhetic acts), illocutionary act (the act that is being done in uttering a performative) and perlocutionary act (act of the speaker in eliciting a certain response from the hearer, or in making an effect on the hearer) (Mabaquiao, 2018; Austin, 1975). John Searle, a prominent American analytic philosopher, inherited some of Austin’s ideas and modified and developed speech act theory. Searle preferred the term “speech acts” to Austin’s performatives and used it to refer to illocutionary acts. Searle divided a speech act into utterance acts (consisting of phatic and phonetic acts), propositional acts (consisting of referring and predicating acts), illocutionary acts, and perlocutionary acts (Searle, 1999). Searle practically did not follow Austin’s classification (the only thing he retained was Austin’s commissives). Instead, he developed his own five basic types of speech acts on the basis of three primary dimensions of speech acts, namely, the illocutionary point, direction of fit, and sincerity condition. Under the guidance of 12 dimensions accounting for the differences (the above three are the primary ones), Searle classified speech acts into the following five types: assertives, directives, commissives, expressives, and declarations (Searle, 1976), which are further elaborated in the following speech act analysis section.

Aristotle is the father of Western rhetoric, and Kenneth Burke is undoubtedly the most influential scholar in modern rhetorical thinking in the United States (Ju, 2005). While classical and modern rhetoric has their roots in “persuasion”, Burke advocated the replacement of “persuasion” with “identification”. Moreover, he proposed that the success or failure of persuasion depends on whether the audience ‘identifies’ with the speaker (Liu, 2008, p. 345). On this basis, Burke proposed the identification theory. Identification theory is an expansion and extension of classical rhetoric. Identification can be achieved in three ways: identification by sympathy, identification by antithesis, and identification by inaccuracy (Burke, 1966). Identification by sympathy emphasizes shared feelings between people, particularly through putting themselves in each other’s shoes or sharing common feelings, attitudes, opinions, values, etc. Identification by antithesis emphasizes unity and cohesion through division, where two individuals achieve temporary identification because they are confronted with a common enemy or problem. Identification by inaccuracy emphasizes the rhetor’s ability to make the audience unconsciously identify with the rhetor through verbal or nonverbal language. Burke suggested that the study of rhetoric should not be limited to spoken and written texts but could also be extended to other areas, such as promotion, courtship, social etiquette, education, witchcraft, literature, and painting. Burke’s definition of rhetoric also includes nonverbal elements, and he believed that nonverbal language could fulfil a persuasive function as well (Burke, 1966).

Burke proposed that where there is persuasion, there is rhetoric (Burke, 1966). Tan (2000) and Zong and Zhao (1997) agreed that rhetorical tradition has focused mostly on the rhetoric of expression at the expense of neglecting the rhetoric of reception. As Burke (1966) suggested, identification is both the destination of rhetoric and the means to achieve it. The study of the rhetoric of reception from an identification perspective would broaden the vision of rhetoric. Therefore, the reception rhetoric is the focus of this identification analysis.

Herring and Dainas (2017) suggested that emojis have the following functions in speech acts: action, reaction, tone modification, narrative sequence, mention, and riff. In their study, the mention function of emojis refers to the emojis themselves, in contrast to the communicative uses of emojis. For example, two heart emojis in “Love  for the scenery and actress in the vlog” are mentions of love. Reaction is defined as an emoji use that depicts an emotional response to content that was posted earlier in the thread, typically in the initial prompt. For example, when A expresses that they are friendly neighbours for a long time, B, as a neighbour of A, responds with an emoji

for the scenery and actress in the vlog” are mentions of love. Reaction is defined as an emoji use that depicts an emotional response to content that was posted earlier in the thread, typically in the initial prompt. For example, when A expresses that they are friendly neighbours for a long time, B, as a neighbour of A, responds with an emoji  to express B’s affection and friendliness to A. Riff, a humorous elaboration on, play on, or parody of a previous emoji or text comment. For example, a Mandarin comment on a Fujian province communication vlog read as follows: “This is a vlog of the southern part of Fujian communication

to express B’s affection and friendliness to A. Riff, a humorous elaboration on, play on, or parody of a previous emoji or text comment. For example, a Mandarin comment on a Fujian province communication vlog read as follows: “This is a vlog of the southern part of Fujian communication  ”; an image of burying head in the hand and laughing triggered the riffs, a kind of humour. Tone modification is emoji usage that directly modifies the text it accompanies. The emoji functions as a nonverbal, para-verbal, or paralinguistic cue as to how the text should be interpreted. This includes the use of emojis to clarify intent and hedge the illocutionary force of an utterance. For example, the emoji in “Xiamen is a wonderful place for travelling

”; an image of burying head in the hand and laughing triggered the riffs, a kind of humour. Tone modification is emoji usage that directly modifies the text it accompanies. The emoji functions as a nonverbal, para-verbal, or paralinguistic cue as to how the text should be interpreted. This includes the use of emojis to clarify intent and hedge the illocutionary force of an utterance. For example, the emoji in “Xiamen is a wonderful place for travelling  ” provides a paralinguistic cue of approval and awesome. An action is an emoji used to portray a (typically) physical action. An action can sometimes substitute for the predicate in a text comment, similar to

” provides a paralinguistic cue of approval and awesome. An action is an emoji used to portray a (typically) physical action. An action can sometimes substitute for the predicate in a text comment, similar to  in “I

in “I  Xiamen”, which signifies an action of “love”. A narrative sequence is a series of consecutive emojis that tell a story of sorts, similar to the emoji series “

Xiamen”, which signifies an action of “love”. A narrative sequence is a series of consecutive emojis that tell a story of sorts, similar to the emoji series “ ”, indicating “being sick and unhappy and heartbroken”.

”, indicating “being sick and unhappy and heartbroken”.

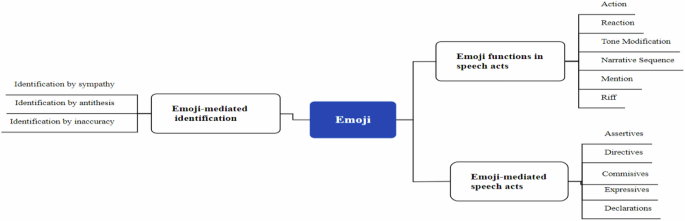

To better serve the purpose of examining emojis from a combined pragmatic and rhetorical perspective as well as the pragmatic functions of emojis in speech acts (Herring and Dainas, 2017), i.e., action, reaction, tone modification, narrative sequence, mention, and riff, we offer a combined theoretical framework, as shown below (see Fig. 1).

Theoretical framework of emoji’s pragmatic and rhetorical features.

Methods

The data of this study come from the vlogs’ comments retrieved by the Chinese hashtag “文旅宣传” (cultural and tourism promotion in English), which are widely collected on the short video platforms Douyin (equivalent to TikTok in America) and Bilibili. Specifically, most statistics in the following tables are obtained from the comments of the Fujian Province (a coastal province in eastern China) cultural tourism promotion video “We are blessed to meet” on the Douyin platform from its release time (November 26, 2020) to June 26, 2023. We chose this specific time duration because, in April 2021, the tourism promotion vlog of He Jiaolong, the secretary of the Department of Culture and Tourism, went viral on the internet, and the vlog as a channel of tourism communication has received increased attention since then. Thus, the time period covers the initial stage, peak, and normalization stage in the employment of vlogs in tourism promotion.

Our survey revealed that “We are blessed to meet” received the most comments among all the vlogs released by official regional cultural and tourism authorities on the Douyin platform. Gao and Zhou (2024) reported that Douyin and Kuaishou attract the most vlog users. “We are blessed to meet”, released both on platforms Douyin and Kuaishou. However, the official video “We are blessed to meet” had 7842 comments and 112,000 likes on Douyin and 84 comments and 17,000 likes on Kuaishou. Therefore, it enjoyed more engagement on Douyin than on Kuaishou. Thus, we chose “We are blessed to meet” on the Douyin platform to be the vlog in question.

To better illustrate the emoji under the theoretical framework, we included specific examples from both the aforementioned vlog of Fujian Province and several official cultural and tourism promotional vlogs from provinces and regions such as Shanxi, Jiangsu, and Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. The figures mentioned in the following sections to illustrate speech acts and identification strategies were collected from the comments of the abovementioned official vlogs both on the Douyin and Bilibili platforms.

Methods

In this paper, two theories (speech act theory and identification theory) and one important finding from Herring and Dainas (2017) were adopted into the discourse analysis of emojis in vlogs’ comments. The specific theoretical framework is shown in Fig. 1. The following procedures were followed in this study: (1) the two authors first chose the vlogs with the largest number of comments and repeatedly visited the comments of the vlogs on Douyin and Bilibili. (2) During the analysis of the comments, we marked and reported the number of comments containing emojis, the speech acts, and the identification strategy the emoji helped with the comments. (3) With respect to the specific speech acts and identification strategy, the two authors discussed and agreed on every speech act and identification strategy performed and realized by emojis. In this way, we satisfactorily collected our first-hand data. With respect to discourse analysis of textual comments, discourse analysis is one of the most popular qualitative analysis techniques. As Krzyżanowski and Wodak (2009) put it, “discourse analysis provides a general framework to problem-oriented social research”. Basically, discourse analysis is used to conduct research on the use of language in context in a wide variety of social problems. In this study, discourse analysis was conducted to explore the speech acts and identification strategy of a comment discourse (emojis included) performed to identify the functions that emojis realize during the performance of speech acts and identification.

Speech acts of emoji-mediated comments on Chinese regional cultural and tourism promotion vlogs

As mentioned, “We are blessed to meet” had the largest number of comments among all the vlogs released by official regional cultural and tourism authorities up to 26 June 2023. Additionally, given its dramatically greater degree of engagement on Douyin than on Kuaishou, we referred to the comments of this video as the corpus for our statistical analysis. This officially revealed 7842 comments, including viewer B’s likes on viewer A’s comments, but the likes of the comments are not the textual form of comments to be counted in this study. After manual counting, 2350 comments were presented in “We are blessed to meet” (not including likes), 940 of which contained emojis; thus, 40% of the 2350 comments contained emojis, a percentage that again proved the indispensability of emojis in daily online communication. Among the 940 emoji-included comments, there is a total of 29 kinds of emojis included after our manual counting and the emojis in the order of frequencies are as follows:  (thumbs up),

(thumbs up),  (love),

(love),  (bury head in the hands and laugh),

(bury head in the hands and laugh),  (flower),

(flower),  (applause),

(applause),  (feel aggrieved),

(feel aggrieved),  (thanks),

(thanks),  (666, means smooth and successful),

(666, means smooth and successful),  (geili in Chinese, means awesome and impressive),

(geili in Chinese, means awesome and impressive),  (smile),

(smile),  (supercilious look),

(supercilious look), (Stuck-Out Tongue),

(Stuck-Out Tongue),  (frown),

(frown),  (naughty),

(naughty),  (sinister smile),

(sinister smile),  (snicker),

(snicker),  (awkward),

(awkward),  (face with tears of joy),

(face with tears of joy),  (dizzy and confused),

(dizzy and confused),  (supercilious look),

(supercilious look),  (angry),

(angry),  (grin),

(grin),  (bye),

(bye),  (cup one fist in the other hand, a sign of respect),

(cup one fist in the other hand, a sign of respect),  (surprise),

(surprise),  (kiss),

(kiss),  (a flash of wit),

(a flash of wit),  (nose-picking),

(nose-picking),  (Ruhua in Chinese, a film character, means tease and ridicule). The emoji with the greatest and overwhelming frequency is

(Ruhua in Chinese, a film character, means tease and ridicule). The emoji with the greatest and overwhelming frequency is  , which is utilized in 560 comments, followed by

, which is utilized in 560 comments, followed by  in 175 comments,

in 175 comments,  in 78 comments,

in 78 comments,  in 71 comments, and

in 71 comments, and  in 56 comments. The frequency with which those emojis are used reveals the communicative effect of the vlog.

in 56 comments. The frequency with which those emojis are used reveals the communicative effect of the vlog.

Among the 940 comments containing the aforementioned emojis, each comment with an emoji is a speech act, and the distribution of the five major speech acts under Searle’s classification is shown in Table 1. There were 47.4% and 46.4% expressive acts and assertive acts, respectively, which together constituted 93.8% of the speech acts mediated by emojis. Emoji-mediated commissive and directive speech acts are relatively rare, mainly because vlog viewers are equally separate online individuals.

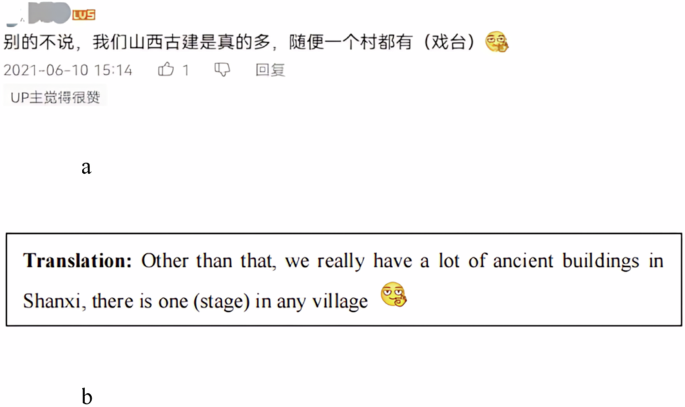

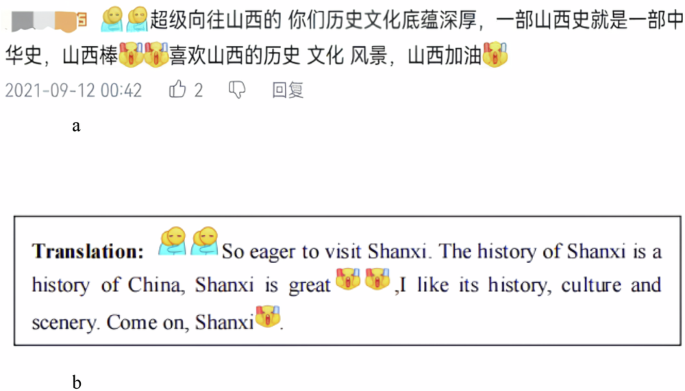

In Searle’s classification of speech acts, the assertive speech act refers to the interlocutor’s statements, descriptions, classifications, and explanations. The following is a comment made by a viewer watching a promotion of cultural tourism in Shanxi, and the  emoji (okay emoji) that appears at the end is a statement and confirmation of the fact presented in the vlog that there are many ancient buildings in Shanxi from the perspective of Shanxi natives, especially ancient stages for acting in every village (see Fig. 2). Therefore, the assertive act was performed when viewers shared their own experiences and knowledge about the people, scenery, and culture in the promoted regions after watching the video. The viewer shared their own perceptions of the situation in Fujian (a province in southern China), and the emoji

emoji (okay emoji) that appears at the end is a statement and confirmation of the fact presented in the vlog that there are many ancient buildings in Shanxi from the perspective of Shanxi natives, especially ancient stages for acting in every village (see Fig. 2). Therefore, the assertive act was performed when viewers shared their own experiences and knowledge about the people, scenery, and culture in the promoted regions after watching the video. The viewer shared their own perceptions of the situation in Fujian (a province in southern China), and the emoji  in the middle or end of the sentence helped consolidate the viewer’s confidence in the information in another example from the vlog “We are blessed to meet”.

in the middle or end of the sentence helped consolidate the viewer’s confidence in the information in another example from the vlog “We are blessed to meet”.

a Assertives (Chinese) and b assertives (English translation).

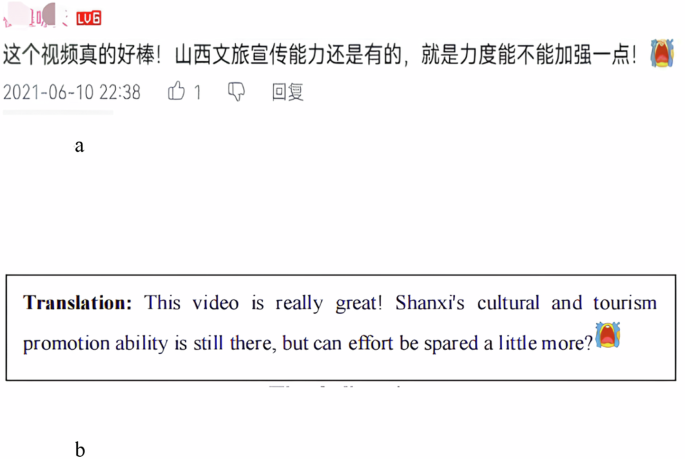

A directive speech act is one in which the speaker instructs the hearer to do something to varying degrees. Verbs that express such acts include “command, request, beseech, allow, permit, ask, urge, demand, order”, etc. In Fig. 3, the viewer makes a request to the authority who produced the vlog, and the [ ] emoji (signifying crying) at the end expresses the earnestness of this request (see Fig. 3).

] emoji (signifying crying) at the end expresses the earnestness of this request (see Fig. 3).

a Directives (Chinese). b Directives (English translation).

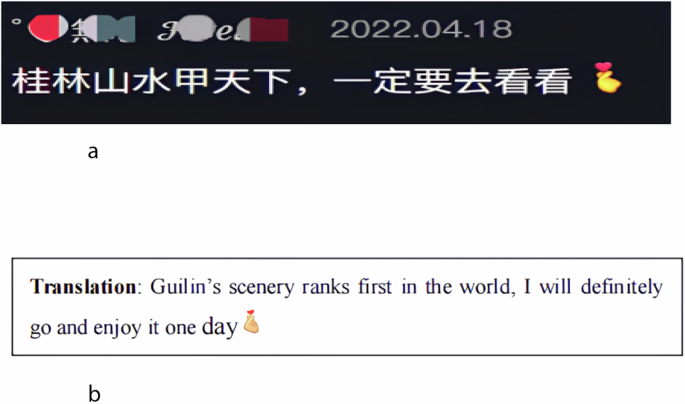

The verbs used to express commissives include “commit, promise, vow, threaten, pledge, offer, and guarantee”. In Fig. 4, the viewer used the [ ] emoji (signifying love) to express his recognition of the Guilin scenery, thus making a personal promise to “definitely go and enjoy it” (see Fig. 4).

] emoji (signifying love) to express his recognition of the Guilin scenery, thus making a personal promise to “definitely go and enjoy it” (see Fig. 4).

a Commissives (Chinese). b Commissives (English translation).

Expressive speech acts refer to the accompanying mental states of viewers while expressing the propositional content of the discourse, such as apologies, boasts, toes, deplore, etc. The viewer in Fig. 5 was clearly not from Shanxi but expressed his recognition and love for the historical and cultural landscape of Shanxi through text and [ ] (signifying hug) [

] (signifying hug) [ ] (signifying love) emojis (see Fig. 5). Additionally, expressive speech acts were performed to disclose viewers’ fondness and disgust.

] (signifying love) emojis (see Fig. 5). Additionally, expressive speech acts were performed to disclose viewers’ fondness and disgust.  emojis consolidated the viewer’s fondness for Fujian promoted in the vlog’s comments in question.

emojis consolidated the viewer’s fondness for Fujian promoted in the vlog’s comments in question.

a Expressives (Chinese). b Expressives (English translation).

Declarations in speech acts usually result in a change in the state of affairs. Additionally, reality would be in line with the declarations once it is performed. The verbs used in English to express declarative acts are “enact, declare, resign, name”, etc. The person performing the declaration speech act is usually empowered with the right or status to bring about a change in the state of affairs. For example, a priest declaring a man or woman as a husband or wife would endorse a legitimate marriage. In fact, it is still difficult for the average viewer to achieve a change in reality by commenting on a vlog. Therefore, declaration speech acts were rarely found in the comments of the vlog in question. However, if a viewer expresses some suggestions or points out some unsatisfactory or missing information about the vlog with comments containing emojis in one day and the authority makes some changes or additions to the regional promotion on the basis of the suggestions, then we would render suggestion-like comments perform speech acts of declaration when the change happens. Unfortunately, such interactions between authorities and viewers are currently lacking.

The abovementioned four existing speech acts are performed via the mediation of emojis. Most comments are presented with both verbal language and emojis. However, it is worth mentioning the speech acts performed with only emojis. After manual counting and checking, there were a total of 79 comments with only emojis included in the comments of the vlog “We are blessed to meet”. The emojis included are as follows:  . The

. The  emoji with three instances of the number “6” means smooth, successful, or good wishes in China.

emoji with three instances of the number “6” means smooth, successful, or good wishes in China.  is another emoticon with the Chinese character “给力”, which means awesome and impressive. Therefore, eight of the nine emoticons mean approval and applause for the successful communication of the vlog. However, the last emoji means “dizzy” or “faint”, which represents the disapproval of and unsuccessful communication of the vlog. Regardless of the approval or disapproval of the vlog, these emoticons perform speech acts of expressiveness because these emoticons demonstrate viewers’ affection or dislikes. Our analysis revealed that comments with only emojis perform certain speech acts, such as expressive. However, in most cases, these emojis helped reinforce and strengthen the illocutionary forces that the verbally textual comments were performing.

is another emoticon with the Chinese character “给力”, which means awesome and impressive. Therefore, eight of the nine emoticons mean approval and applause for the successful communication of the vlog. However, the last emoji means “dizzy” or “faint”, which represents the disapproval of and unsuccessful communication of the vlog. Regardless of the approval or disapproval of the vlog, these emoticons perform speech acts of expressiveness because these emoticons demonstrate viewers’ affection or dislikes. Our analysis revealed that comments with only emojis perform certain speech acts, such as expressive. However, in most cases, these emojis helped reinforce and strengthen the illocutionary forces that the verbally textual comments were performing.

As aforementioned, there were 79 comments with only emojis in total that performed speech acts independently among the 940 comments, accounting for 8.4% of all comments. The remaining 91.6% (861) of the comments performed speech acts together with verbal textual information. The role that emojis play in 91.6% of the total comments is mostly rhetorical, that is, reinforcing and consolidating the speech acts that the verbally textual comments performed.

Emojis’ pragmatic functions in comments on Chinese regional cultural and tourism promotion vlogs

What pragmatic functions do emojis perform in the realization of speech acts? The distributions of the six types of functions of emojis in vlog comments are shown in Table 2. Statistical analysis revealed that the action function of emojis was the most prominent, accounting for 37.2%, with the highest frequencies of [ ], [

], [ ], and [

], and [ ] emojis to represent hug, affection, and love, respectively. The second highest percentage was the reaction function of emojis (accounting for 19.8%), which mainly demonstrated reactions after the promotion video and the use of emojis to express feelings and perceptions. The smallest proportion is the riff function (0.6%), which refers mainly to the humorous interactions between viewers. There is less interaction between viewers on the Douyin platform and more interaction and feedback on the content of vlogs from viewers. In the study of Herring and Dainas (2017), the reaction and tone modification functions of emojis accounted for 34.3% and 25.3%, respectively, and in third place, the mentioned function accounted for 18.3%. The proportions of emojis’ major pragmatic functions in Table 2 clearly differ from those in Herring and Dainas (2017). We believe that the discrepancy between this study and Herring and Dainas’ (2017) findings stems mainly from differences in the statistical corpus. Herring and Dainas (2017) studied the function of emojis in comments on Facebook, where both sides of the communication focus on interactions between individuals or even friends, and both parties can interact with each other instantly, so the reaction function of emojis in their study ranked first and tone modification second. In contrast, the statistics in this study come from the comments of vlogs, whose viewers cannot further communicate and interact with authorities or producers of vlogs. Therefore, the functions of emojis are distributed more in feedback, such as actions and reactions, after watching vlogs.

] emojis to represent hug, affection, and love, respectively. The second highest percentage was the reaction function of emojis (accounting for 19.8%), which mainly demonstrated reactions after the promotion video and the use of emojis to express feelings and perceptions. The smallest proportion is the riff function (0.6%), which refers mainly to the humorous interactions between viewers. There is less interaction between viewers on the Douyin platform and more interaction and feedback on the content of vlogs from viewers. In the study of Herring and Dainas (2017), the reaction and tone modification functions of emojis accounted for 34.3% and 25.3%, respectively, and in third place, the mentioned function accounted for 18.3%. The proportions of emojis’ major pragmatic functions in Table 2 clearly differ from those in Herring and Dainas (2017). We believe that the discrepancy between this study and Herring and Dainas’ (2017) findings stems mainly from differences in the statistical corpus. Herring and Dainas (2017) studied the function of emojis in comments on Facebook, where both sides of the communication focus on interactions between individuals or even friends, and both parties can interact with each other instantly, so the reaction function of emojis in their study ranked first and tone modification second. In contrast, the statistics in this study come from the comments of vlogs, whose viewers cannot further communicate and interact with authorities or producers of vlogs. Therefore, the functions of emojis are distributed more in feedback, such as actions and reactions, after watching vlogs.

Emojis’ rhetorical identification in comments on Chinese regional cultural and tourism promotion vlogs

Again, referring to the cultural tourism promotion vlog “We are blessed to meet” as statistical materials, there were a total of 2,350 substantive comments and 940 comments mediated with emojis. As shown in Table 3, we found that identification by sympathy accounted for the largest percentage (62.3%) of the 940 emoji-mediated comments. Although both identifications by antithesis and inaccuracies lack explicit approval and endorsement, they imply and reflect the audience’s approval of the vlog’s promotion, i.e., communicative and rhetorical effectiveness. Identification by sympathy, antithesis, and inaccuracy together made up 72.7% of identification with the regional promotion, which reflected the success of the rhetorical activity of the vlog. The other 27.2% were vague identifications or disapprovals of the vlog; thus, the vlog’s rhetoric was not very effective for 27.2% of the comments. The discourse and content analysis of the comments in the vlog revealed that some viewers discussed or commented and even criticized the content absent from the vlog, thus implying vague identifications or even a failed communicative effect of the vlog.

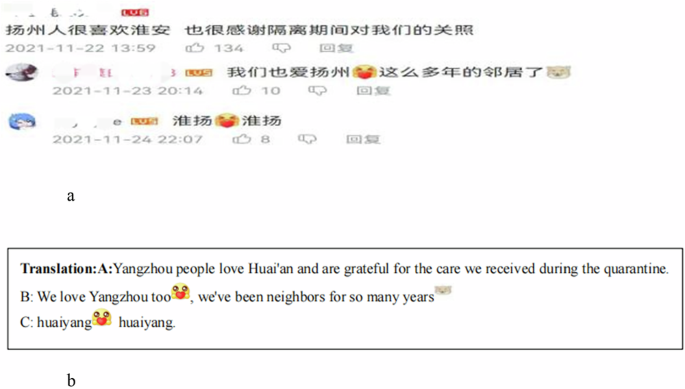

Burke’s identification theory, which is more than a rhetoric strategy, serves as the aim and goal of communication, i.e., communicative effectiveness. Identification by sympathy emphasizes shared feelings between people, particularly through putting themselves in each other’s shoes or sharing common feelings, attitudes, opinions, values, etc. In the comment shown in Fig. 6 (a comment on the promotion of cultural tourism in Huai’an, a city in Jiangsu Province, in the eastern region of China), these three viewers found some kind of identification with each other due to their geographical, historical, and cultural ties (see Fig. 6). Therefore, they were identified with each other after viewing the vlog. Such sympathy is reinforced by the [ ] emoji (signifying love) in the comments.

] emoji (signifying love) in the comments.

a Identification by sympathy (Chinese). b Identification by sympathy (English translation).

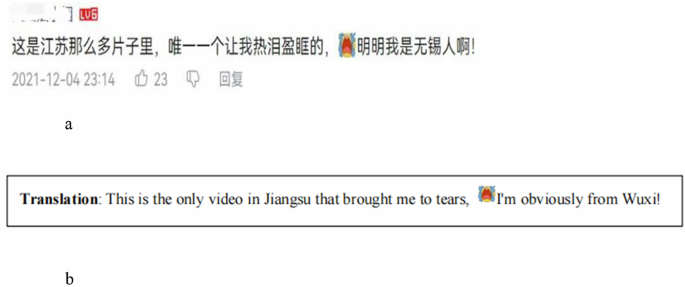

Identification by antithesis emphasizes unity and cohesion through division, where two individuals achieve temporary identification because they are confronted with a common enemy or problem. Figure 7 is also derived from a comment on the promotion of cultural tourism in Huai’an (see Fig. 7). The commentator is a Wuxi (another city in Jiangsu Province) native, but he was touched by Huai’an’s promotion. Therefore, this viewer’s temporary attraction and identification with Huai’an was opposed to his or her real hometown identity as a Wuxi native and finally identified with the Huai’an promotion vlog, thus achieving an antithesis between his or her identity as a Wuxi native and identification with Huai’an. The [ ] emoji (signifying crying) strengthened the antithesis.

] emoji (signifying crying) strengthened the antithesis.

a Identification by antithesis (Chinese). b Identification by antithesis (English translation).

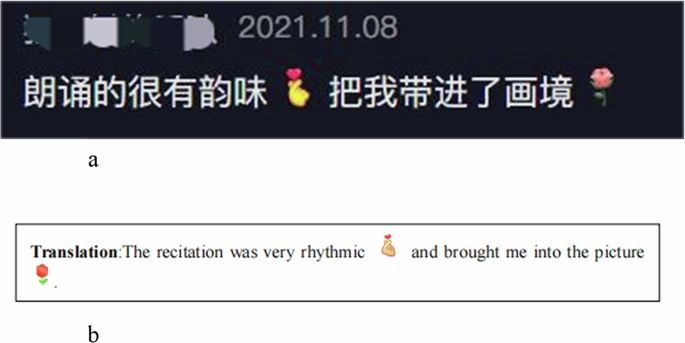

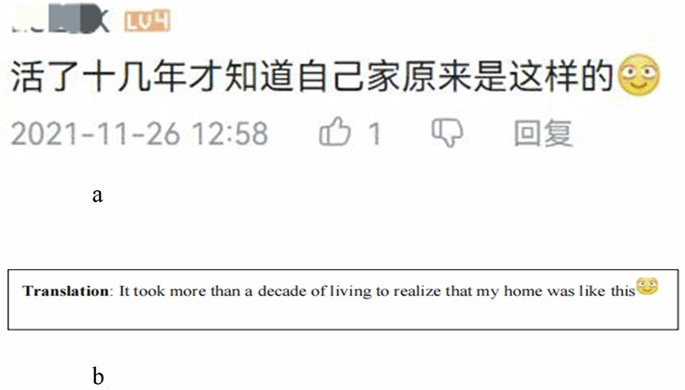

Identification by inaccuracy emphasizes the rhetor’s ability to make the audience unconsciously identify with the rhetor through verbal or nonverbal language. Figure 8 shows a comment on a promotional vlog on the cultural tourism of Guangxi Province (see Fig. 8). Whereas the viewer was not present in the scenery of Guangxi, the promotion vlog brought about the illusion as if he were enjoying the beautiful scenery on the spot, thus achieving identification by inaccuracy. Both  (signifying love) and

(signifying love) and  (signifying praise and approval) are recognized and complement the recitation and scenery presented in the vlog. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 9, after watching the promotional vlog of the hometown, the viewer found that his or her perception of the hometown is inconsistent with the presentation of the vlog, resulting in identification with the promotion in inaccuracy (see Fig. 9).

(signifying praise and approval) are recognized and complement the recitation and scenery presented in the vlog. Similarly, as shown in Fig. 9, after watching the promotional vlog of the hometown, the viewer found that his or her perception of the hometown is inconsistent with the presentation of the vlog, resulting in identification with the promotion in inaccuracy (see Fig. 9).  (signifying smile and surprise) at the end reinforces the identification.

(signifying smile and surprise) at the end reinforces the identification.

a Identification by inaccuracy (Chinese). b Identification by inaccuracy (English translation).

a Identification by inaccuracy (Chinese). b Identification by inaccuracy (English translation).

The regional cultural and tourism promotional vlog is a rhetorical activity of the cultural and tourism authority for a wide audience. Edward Hall’s theory of interaction suggests that rhetorical activity is an interactive act in which the speaker and the listener are mutually transformable (Feng, 1999). The rhetorical tradition has traditionally emphasized the rhetoric of expression over the rhetoric of reception. For this reason, the Chinese scholar Chen Wangdao proposed conducting rhetorical research on listeners and receivers of speech. Zong and Zhao (1997) suggested that the main reason for the long neglect of the rhetoric of reception was that “language-oriented” structuralism had been stuck to static formal studies such that active factors such as subject consciousness in the communicative process were ignored. Thus, we concentrated on the rhetoric of reception, which was manifested in the comments made by viewers. Additionally, we found that rhetorical research has a preference for verbal language over other nonverbal languages after conducting research on prior studies. In fact, nonverbal language, such as emojis, can also convey the audience’s or recipients’ sense of subjectivity very well and deserves our attention in rhetorical studies.

Discussion and conclusion

Vlogs, as newly emerging one-to-many media for CMCs that can be synchronous and asychronous, enjoy great popularity both domestically and internationally, both personally and officially. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, many Chinese tourism authorities have been rushing into vlog employment to advocate and promote regional beauty in various forms. Moreover, the emoji, a paralinguistic element that prevails and is highly preferred in CMC, needs to be examined as a kind of network language and culture in China. The current study probed the speech acts of emoji-mediated comments, pragmatic functions and their distributions, rhetorical identification and their distribution through the mediation of emojis in comments made by viewers of vlogs advocating regional culture and tourism, which were released by Chinese regional authorities of culture and tourism.

Along with other verbally textual information, emojis perform the following four speech acts: expressives, assertives, commissives, and directives, among which expressives and assertives speech acts rank first and second, respectively, and together constitute 93.8% of the emoji-mediated speech acts. Speech acts of declaration have not been identified in the vlogs’ comments in this study, which seems to be a characteristic of emoji-mediated speech acts in the vlogs’ comments. According to Austin and Searle’s theoretical perspective on speech acts (Austin, 1963, 1975; Searle, 1976, 1999), declaration speech acts usually lead to a change in the state of affairs, and the person performing the declaration speech act is usually empowered with the right or status to bring about a change in the state of affairs. However, in the comments of the vlog, the viewer, as an average netizen, does not have the power to change the state of affairs. Therefore, declaration speech acts are rarely found in the comments of the vlog in question at present. The lack of emoji-mediated speech acts of declarations in our study implies that tourism-advocating authorities should pay more attention to the comments of the released vlog because comments from viewers would provide avenues for improvement for future regional promotion. Notably, the illocutionary forces performed via emojis are very much contextually dependent on verbal words or sentences. Some frequently used emojis are polysemous in speech acts helping performed or achieved because a specific emoji shows its presence in several different contexts, thus leading to the correspondence between a speech act and a specific emoji being difficult to determine, as in the case of correspondence between emojis’ pragmatic functions and their role in achieving rhetorical identification with a specific emoji.

To help realize the speech acts in the comments of the vlog, emojis performed the following major pragmatic functions: action and reaction, accounting for 57% of all the emoji pragmatic function distributions, which differ from the findings of Herring and Dainas (2017), in which reaction and tone modifications constitute the largest percentage. The discrepancy between the findings of this study and Herring and Dainas’ (2017) findings may suggest different pragmatic emoji functions between social media Facebook and newly emerging vlogs. Because Facebook is convenient for interaction between individuals, they adopt emoticons to react and modify tones, which highlights more features of interpersonal online communication between individuals. Given that cultural and tourism vlogs are more concentrated in organizational communication, individuals adopt emojis to respond to actions and reactions to online organizational communication, with less involvement of personal interaction, which might lead to the difference between our study and Herring and Dainas’ (2017). The discrepancy between Herring and Dainas’ study and our study provides some hints regarding the participation and interaction of the authorities in comments, especially in answering some questions raised by the audience.

In the same vein, regional cultural and tourism promotion vlogs provide platforms for rhetorical activities from cultural and tourism authorities, with the general audience as the target of rhetoric. Tan (2000), Zong and Zhao (1997) revealed that rhetorical tradition has focused mostly on the rhetoric of expression at the expense of neglecting the rhetoric of reception. As Burke (1966) suggested, identification is both the destination of rhetoric and the means to achieve it. In the vlogs of cultural and tourism promotion, on the one hand, multimodal information such as video, sound, verbal text, and images are presented to engage the viewer, draw identification, and achieve communicative effectiveness. On the other hand, likes, follows as well as comments of vlog viewers imply the rhetorical acceptance or communicative effectiveness of vlogs as a rhetorical activity. Some viewers identify with the information displayed in the vlogs through sympathy, antithesis, and inaccuracy by making comments below with texts as well as nonverbal language emojis. These three identifications (accounting for 72.7% of the comments analysed) realized through texts and/or emojis represent the successful promotion and rhetorical effectiveness of cultural tourism vlogs. Rhetorical activity does not end when viewers’ comments are given, and each comment may act as a rhetorical party, opening a new round of rhetorical activity with the comment readers or the vlog authorities as the rhetorical audience. Moreover, as in the case of the rhetoric of expression, an exploration into the rhetoric of reception from an identification perspective is worth our attention, and we would gain more insights into the communicative effect and effectiveness of regional promotion vlogs, as well as insight into the features of online rhetorical reception. Although 72.7% of the emoji-mediated comments showcase viewers’ positive identification with the vlog “We are blessed to meet”, the other 27.2% of the comments represent identification and communication failure. These comments on failed identification are valuable and conducive to tourism advocating, in general, for departments of culture and tourism.

Research on language must simultaneously promote a sophisticated understanding of its complex and multiple facets of language. Thus, examining language from one discipline or several isolated disciplines is insufficient (Liu, 2015). Multiple disciplinary perspectives need to be integrated into the study of emojis in regional promotional vlogs and their comments to enhance the understanding of this phenomenon. Rhetoric, referring to all meaningful expressive activities, has its origins in ancient Greece and a long humanistic history, with “persuasion” as its goal in ancient times and “identification” as its aim in modern times (Aristotle, 2007; Burke, 1966). Pragmatics is a linguistic science derived from the framework of modern linguistics. In recent years, it has been combined with cognitive science to focus on the understanding of and response to intentions. We can observe the linguistic phenomenon of emojis in vlogs’ comments either from a rhetorical or pragmatic perspective alone or by combining pragmatic and rhetorical perspectives.

The combination of the two reveals that presented regional promotion vlogs were uploaded online to a wide audience with the intention of “communicative effectiveness or attraction” and “achieving identification”. Therefore, pragmatic intention and the goal of rhetorical identification were evident and highly overlapping. Whether viewers were aware of these intentions and purposes or not, they expressed certain attitudes through their own actions, such as liking, following or ignoring, or disliking, or they performed speech acts through texts or emojis. While performing speech acts, the audience also reacted to the rhetorical activity of vlogs with some rhetorical effect via verbal or nonverbal elements such as emojis. Emojis help perform and consolidate speech acts and communicate the rhetorical effect. The emoji was equivalent to gestures and facial expressions in face-to-face communication, allowing speech acts and rhetorical identification to be better realized and making communication more economical, efficient, and fun.

Above all, emojis have undoubtedly become the most widely discussed new language in social media. Emoji socialization can concisely express one’s feelings, construct a discourse space outside the mainstream, and bridge the distance between the communicating parties, which is in line with the trend of virtual socialization. Additionally, the emojis used in our study helped perform speech acts, fulfilled certain pragmatic functions, and achieved rhetorical identification in vlog comments. However, we agree with Jing (2020) and Crystal (2005) that the negative influence of emojis as a network language and the internet is also noteworthy. Emoji communication, as a form of internet linguistics, lacks in-depth, meaningful conversation and sometimes simultaneous feedback and tends to ignore traditional language expression, logic, and rules.

The limitations of this study are threefold. First, this study explored speech acts and the pragmatic functions performed and realized via the mediation of emojis in the comments of several mentioned vlogs, so the findings may not be representative and inclusive of those of the emoji study. Moreover, although speech acts and rhetorical identification strategies, which are mediated by emojis, are discussed in this study, the correspondence between speech acts, identification strategies and certain emojis is not identified and revealed. Furthermore, a communicative effect comparison between textual language and independent emojis is lacking, which would better reveal the strengths and weaknesses of emoji communication and its influence on network communication. For future research, more forms of emojis in computer-mediated communication, more specific emojis and their communication strengths, weaknesses and influence can be targeted. In summary, emojis, as computer-mediated nonverbal language, have the same responsibility and functions as verbal language in online communication, helping online users perform pragmatic speech acts and pragmatic functions and achieve communicative identification.

Responses