Escherichia Coli K1-colibactin meningitis induces microglial NLRP3/IL-18 exacerbating H3K4me3-synucleinopathy in human inflammatory gut-brain axis

Introduction

Escherichia coli K1 (E. coli K1) is a highly virulent bacterial pathogen that frequently causes neonatal meningitis, causing gastrointestinal symptoms at the early stage1 and long-term neurological issues in over half of survivors2. Clinical reports have shown rectovaginal colonization of E. coli K1 in pregnant women is associated with the high risk of vertical transmission to their infants’ gut during childbirth3,4,5. Additionally, E. coli K1 meningitis exhibits severe gut dysbiosis6, high levels of inflammatory cytokines in the bloodstream7, and brain damage8. These findings highlight the systemic detrimental effects of E. coli K1 infection, indicating that the gut-brain axis (GBA) may be a potential route for E. coli K1-induced meningitis.

The initial infection of the gut by E. coli K1 is facilitated by changes in the intestinal microbiota composition, leading to gut dysbiosis9. Within this dysbiotic microenvironment, E. coli K1 capitalizes on its virulence factors, such as genotoxic colibactin to adhere to and invade the intestinal epithelium (EP), breaching the gut barrier10. Especially, E. coli K1 can evade the host immune system due to the expression of capsule polysaccharide K1, a virulence factor that confers hostility to host cells’ complement-mediated killing11. Additionally, the outer membrane protein enables E. coli K1 to evade phagocytosis by host macrophages through interactions with immune inhibitory receptors12. E. coli K1 is adept at disrupting blood-brain barrier (BBB) integrity and entering the brain, causing neuroinflammation and neuronal damage13,14,15. This invasion contributes to long-term neurological complications and potentially increases the risk of neurodegenerative disease (ND) onset.

Epidemiological studies suggested that Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients are more likely to have a history of certain infections16,17 or inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)18,19. Several studies have suggested the significant role of genotoxic colibactin-producing E. coli in the pathogenesis of IBD20,21,22, implicating a suspected connection between childhood E. coli K1 meningitis and PD’s etiology. A study demonstrated that 33 out of 34 neonatal isolates of E. coli K1 carried the clbA and clbP genes, which are part of the pks pathogenicity island and are necessary to produce genotoxic colibactin23, a polyketide-peptide genotoxin induces genomic integrity in mammalian cells by initiating DNA damage, such as double-strand breaks (DNA-DSB)24,25.

In the central nervous system (CNS), neurons are more susceptible to DNA damage than glial cells during E. coli K1 meningitis due to their long-lifespan and lack of robust DNA repair mechanisms26. Additionally, microglial phagocytosis of damaged neurons elevates reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, further compromising neuronal DNA integrity27. Recent research has indicated that accumulation of DNA damage may occur before the onset of PD, suggesting its direct participation in neurodegeneration28. Upon DNA damage, chromatin unwinds, enabling repair enzyme access, a process regulated by epigenetic modifications that have been found in samples of PD patients, suggesting its significant role in disease pathology29. Moreover, several studies have found that epigenetic modifier TET1 or autophagy-lysomal system can regulate expression of SNCA gene encoding α-synuclein (α-Syn) protein30,31, which accumulates abnormally as a pathological hallmark of PD. However, the specific mechanism by which E. coli K1 contributes to synucleinopathy is still uncertain.

In addition, it is well known that bacterial meningitis triggers neuroinflammatory responses32,33. Previous research has shown that the K1 capsule prevents direct recognition of the bacteria by microglia while inducing inflammatory responses in both microglia and astrocytes34. As astrocytic end-feet creates direct communication between the vascular system and the neuroglia within the CNS35, astrogliosis may be initiated first upon E. coli K1 infection, which releases antimicrobial pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ36. Interestingly, phagocytic activity of microglia can be promoted by astrocytic IL-4 and IL-10 via upregulation of TREM-2, but it is not clear whether pro-inflammatory cytokines disrupt phagocytosis in microglia37. At present, the role of microglia and astrocyte activation in host defense and immune surveillance during E. coli K1 meningitis remains unclear. Despite these advances, the systemic interplay among E. coli K1, neurodegeneration, and neuroinflammation via the GBA remains poorly understood due to the lack of a multi-organs system for studying step-wise pathogenesis upon E. coli K1 infection.

Although Transwell systems enable the co-culture of gut and brain barrier cells, it is impossible to incorporate blood-derived inflammatory factors between the two barriers complicating real-time imaging of cellular interactions. Organ-on-chips are considered a promising tool for elucidating the role of the human GBA in bacterial infection-induced NDs38,39,40. Therefore, we employed a GBA microfluidic chip as an infectious model to investigate meningitis-inducing neurodegeneration and neuroinflammation of E. coli K1. The GBA chip was reconstructed with all the necessary cellular components, including three main compartments for co-culture of gut EP and bacteria, brain endothelium (EC), tri-culture of neurons, astrocytes, and microglia. This model system allows us to recapitulate the complicated communication among the gut microbiota, the gut-blood-brain barrier (GBBB), and the CNS. Specifically, we hypothesize that E. coli K1 infection will lead to systemic inflammation and dysregulation of H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), resulting in aberrant gene expression patterns associated with the severity of neurotoxic synucleinopathy.

Results

A model of human gut-brain inflammatory axis for studying systemic inflammation and neuropathogenesis associated with E. coli K1 meningitis

To develop the GBA chip system, we co-culture multiple human cells: gut EP, brain EC, neurons, astrocytes, and microglia, in a three-chamber platform connected via microchannels for interfacing and exchanging different cells (Fig. 1a, b). The microfluidic GBA chip was fabricated from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), with three parallel main channels connected to each other by microchannel arrays using standard soft lithographic techniques (Supplementary Fig. 1a–c). The gut EP and CNS channels were designed with dimensions of 100 × 3000 × 5000 μm in height, width, and length while the BBB channel was designed with dimensions of 100 × 600 × 5000 μm in height, width, and length. The interconnection microchannel arrays were designed with dimensions of 3 × 8 × 600 μm in height, width, and length.

a A scheme and images of a gut-brain axis (GBA) platform for the study of gut infection-derived neurodegeneration with three compartments: gut epithelium (EP)/E. coli K1, brain endothelium (EC), and neurons/astrocytes/microglia (Neu./AC/MG). b Timeline of establishing GBA model for E. coli K1 meningitis. c–e Representative fluorescent images of GBA model showing physiological and pathological markers in gut epithelium chamber (αSyn/p-αSyn, VE-Cad), brain endothelium chamber (αSyn/p-αSyn, VE-Cad), and neurons/astrocytes/microglia chambers (Tuj1/Aldh1l1/MG, GFAP/CD86/p65, H3K4me3/αSyn, NeuN/p-αSyn), respectively. f Heat-map showing physiological and pathological markers in gut epithelium, brain endothelium, and neurons/astrocytes/microglia in GBA model. g Heat-map showing systemic multiple cytokines released from individual organ models during E. coli K1 infection in the GBA. All experiments were repeated three times and analyzed in fold changes. Scale bars, 50 μm (insets) and 100 μm (main) in Fig. 1c, e, 20 μm (insets) and 50 μm (main) in Fig. 1d. The full dataset used for Fig. 1 is available in Supplementary Data 1 and 5.

To characterize GBBB function during E. coli K1-colibactin meningitis, we stained the gut EP and brain EC against vascular endothelial-cadherin (VE-Cad), αSyn, and phosphorylated αSyn (p-αSyn) (Fig. 1c, d, f). In our GBA system, E. coli K1 infection caused severe damage in the gut EP and mild injury in the brain EC. The infected gut EP strongly reduced the intensity level of VE-Cad markers indicating disruption of the gut barrier. Our results also observed a reduction in αSyn level while the level of pathogenic p-αSyn was increased dramatically in the E. coli K1-infected gut EP (Fig. 1c), indicating that Caco-2 cells can produce αSyn. Another study showed that Caco-2 cells are able to internalize αSyn aggregates, suggesting their relevance in modeling gut-derived contributions to PD pathogenesis41. In the CNS, E. coli K1 meningitis induced neuroinflammation and neurodegeneration-associated protein markers while reduced physiological markers in neurons, astrocytes, and microglia (Fig. 1e, f). Particularly, we found that E. coli K1 increases astrogliosis and microgliosis, evidenced by inducing level of glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) for reactive astrocytes, CD86 as M1 microglia marker, and p65-NF-κB inflammatory signaling pathway. In addition, we observed epigenetic modification in neurons that happened during E. coli K1 meningitis, evidenced by an increase of H3K4me3 marker. This epigenetic induction associates the promotion of αSyn, which is post-translational modified into p-αSyn, which is a well-known neurotoxic protein in PD. In addition, we found the elevation of several inflammatory cytokines across multi-organs during E. coli K1-colibactin meningitis (Fig. 1g and Supplementary Fig. S2), which emphasized the crucial roles of systemic inflammation in E. coli K1 meningitis-associated neuropathies.

Intestinal and peripheral pro-inflammatory IL-6 predominantly promote BBB damage upon E. coli K1 meningitis

The GBBB is crucial in regulating interaction among the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, the immune system, and the brain in normal physiological conditions and meningitis42. Here, we hypothesized that E. coli K1-colibactin meningitis could lead to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in both the gut EP and brain EC. Prolonged E. coli K1 infection in the gut EP may trigger calcium release from ER stores, subsequently causing an elevation of mitochondrial Ca2+ levels. This leads to mitochondrial ROS production, resulting in dysfunction of the gut barrier, allowing E. coli K1 to enter the systemic circulation. Meanwhile, E. coli K1 can evade detection and clearance by macrophages through various immune evasion strategies43. This evasion enables the bacteria to persist and proliferate, subsequently triggering an immune response, subsequently resulting in elevation of interleukin-6 (IL-6) as reported in patients with E. coli K1 meningitis44,45,46. These elevated levels of IL-6 may contribute to breakdown of the BBB via activation of p38/p65 and NLRP3 priming, facilitating infiltration of E. coli K1 into the CNS (Fig. 2a). To test this possibility, we reconstructed a GBBB in a microfluidic chip by co-culturing gut EP and brain EC in two distinct chambers connected by an array of micro-channels with 20 μm in width and 600 μm in length, which enables the bacteria movement and distinctly separate gut EP and EC to avoid medium shock. In the brain EC chamber, we additionally added soluble IL-6, a representative inflammatory cytokine from peripheral immunity, as observed in blood samples of E. coli K1 meningitis patients7.

a A signaling of how E. coli K1 induces gut-blood-brain barrier disruption in the co-culture of gut epithelium and brain endothelium. b–e Representative fluorescent images and quantitative analysis of calcium influx, Mt ROS, αSyn, and p-αSyn in the gut epithelium and brain endothelium respectively. f, g Representative fluorescent images and quantitative data of p38, p65-NFκB, NLRP3, and VE-Cad markers in the brain endothelium co-cultured with E. coli K1 and of IL-6 (100 ng/mL) treatment. All experiments were repeated four times independently and statistically analyzed by unpaired t test (f, e) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test (g) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Scale bars, 20 μm. The full dataset used for Fig. 2 is available in Supplementary Data 2 and 5.

In the gut EP, E. coli K1-infected cells strongly increased the Rhod2-AM and ROS fluorescent signal fourfold greater than the control group (Fig. 2b, d), indicating calcium accumulation in the mitochondrial matrix induces ROS leading to the gut barrier disruption evidenced by the reduce of VE-Cad marker as previously shown in Fig. 1. In addition, our findings indicated a twofold increase in p-αSyn level in E. coli K1-stimulated gut EP (Fig. 2b, d). Interestingly, we observed a reduction in αSyn expression in the E. coli K1-exposured group (Fig. 2b, d), which suggests a possible mechanism for the phosphorylation of αSyn via mitochondrial dysfunction during E. coli K1-inducing intestinal inflammation. Long-term exposure of gut EP to E. coli K1 acts as a pro-apoptotic signal that triggers the outer membrane to become permeable and facilitates the movement of cytochrome c (cyt c) away from cardiolipin, enabling the release of cyt c into the cytosol47. Cyt c, as a peroxidase, may be able to generate radicals on αSyn, ultimately initiating phosphorylation48.

In the brain EC, we also observed similar scenarios with a slight increase in fluorescent signals of mitochondria Ca2+, ROS, and p-αSyn in E. coli K1-infected cells (Fig. 2c, e). However, we did not observe severe damage to the brain endothelial monolayer during E. coli K1 meningitis in the co-culture model. It has been studied that E. coli K1 can be internalized by endothelial cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis, such as glycoprotein CD14749 or Caspr115. Next, our results illustrated that the E. coli K1-infected co-culture model can only significantly induce the p38-MAPK (Supplementary Fig. 3) and further increased by additional stimulation with IL-6 with twofold and 3.5-fold greater than the control group, respectively (Fig. 2f, g). Mitochondrial ROS can directly trigger p38-MAPK phosphorylation via a mechanism that requires electron flow in the early stages of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, implying that either hydrogen peroxide or superoxide is involved in stimulating this process50. Also, we found that IL-6 initiated signaling cascades that release p65-NFκB for nuclear translocation and transcriptional activation (Fig. 2f, g) with 4-fold greater than control. Moreover, paired activation of p38/p65 promotes the NLRP3 priming leading to brain barrier disruption (Fig. 2f, g). In particular, the NLRP3 level increased 1.5-fold and fourfold without and with soluble IL-6 exposure, respectively. Similarly, the signal of VE-Cad marker reduced 1.5-fold in treatment with co-stimulated brain EC. Both p38-MAPK and p65-NFκB are capable of regulating the transcriptional expression of genes that participate in the inflammatory response, including components of the NLRP3 inflammasomes and upregulating pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Reactive astrocytic IFN-γ inhibits microglial phagocytosis, exacerbating neuroinflammation during E. coli K1 meningitis

During bacterial meningitis, astrocytes and microglia orchestrate vigilant immune surveillance within the CNS to combat the invading pathogens. However, dysregulated immune activation may lead to excessive neurotoxic neuroinflammation. In this study, we hypothesized that the BBB-penetrated E. coli K1 may first encounter astrocytes via recognizing pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) from the bacteria due to the end-feet of astrocytes making direct contact with the BBB. This recognition could trigger the generation of IFN-γ and reactive astrogliosis at an early stage of meningitis, which may worsen due to inflammatory mediators from BBB damage. We did not observe the elevation of IFN-γ in microglia (Supplementary Fig. 4). Coincidently, the E. coli K1 itself can escape microglial phagocytosis via K1 capsule as reported in previous studies and activate mild microgliosis via PAMPs during their invasion in the CNS. More importantly, we proposed that reactive astrocytic IFN-γ could inhibit microglial phagocytosis of E. coli K1, reducing their ability to clear the invading pathogens effectively. As a result, this dysregulated microglial response contributes to the amplification of detrimental neuroinflammation (Fig. 3a). To test this hypothesis, we established central immune surveillance-on-a-chip by co-culturing human immortalized microglia and astrocytes with/without the presence of E. coli K1-stimulated brain EC conditioned medium (K1BBBCM) in astrocytes and IFN-γ in microglia.

a A signaling of E. coli K1 inducing detrimental neuroinflammation. b, c Fluorescent images and quantification of inflammatory (NF-κB, GFAP, IFN-γ) in astrocytes. d Representative images of inflammatory markers (NF-κB, CD86) and phagocytic markers (LC3b and TREM-2) in microglia with paired activation of IRF3 and NLRP3, inciting neuroinflammation evidenced by elevation of iNOS, NO, ROS. e–i Quantification of inflammatory and phagocytic markers in single culture microglia with and without IFN-γ. k, j Fluorescent images and quantification showing IFN-γ reduce microglial engulfment of E. coli K1 in meningitis. All experiments were repeated four times independently and statistically analyzed by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test (Fig. 3c, e–i) and unpaired t test (Fig. 3k, j) (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). All data were presented as the mean ± standard. Scale bars, 20 μm in Fig. 3b and 50 μm in Fig. 3d, k. The full dataset used for Fig. 3 is available in Supplementary Data 3 and 5.

In astrocytes, we found an elevation of fluorescent signals across several reactive markers, including NF-κB, GFAP, IFN-γ in single and co-culture models in the bacteria-infected groups (Fig. 3b, c). In the single culture of astrocytes, E. coli K1 itself increased the level of NF-κB, GFAP, and IFN-γ with 2.5-fold, 2-fold, and 2-fold greater than the control of the single astrocytes model, respectively. Interestingly, all the astrocytic markers were significantly increased with the presence of K1BBBCM during E. coli K1 infection, particularly 4-fold, 3-fold, and 4-fold greater than the non-infected group. Moreover, we revealed the interaction of microglia and astrocytes during E. coli K1 meningitis evidenced by the increase of reactive astrocytic markers in the E. coli K1-stimulated group compared to the control, with 3-fold, 2.5-fold, and 2.5-fold for NF-κB, GFAP, and IFN-γ, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). The astrocytic NF-κB signaling has been reported in common neurodegenerative astrogliosis51 and in bacterial metabolites-induced astrogliosis52. Previous studies also showed the increase in GFAP level in cerebrospinal fluid of meningitis patients53,54,55. In acute infection, it has been shown that astrocytes are able to release type I interferon such as IFN-β56, however, the role of astrocytic type II interferon like IFN-γ has been barely studied. Here, we showed excessive elevation of IFN-γ in E. coli K1 meningitis in the presence of inflammatory mediators from BBB damage, which highlights the synergistic interaction between vascular and astrocytic inflammation during meningitis.

After observing astrogliosis during E. coli K1 neuroinfection, our study continues to reveal the pivotal role of microglia in the pathophysiology of bacterial meningitis. We used the single and co-culture models as previously described in Fig. 3d & Supplementary Fig. 4 to investigate how microglia respond to E. coli K1 both on their own and alongside astrocytes. In the single culture of microglia, our results indicated slight increases in NF-κB and CD86 markers, suggesting microglial inflammation, with nearly 2.5-fold and 1.5-fold higher than the control for NF-κB and CD86, respectively (Fig. 3e). Upon observing elevated levels of IFN-γ in stimulated astrocytes, we added soluble IFN-γ into the single culture model of microglia which resulted in an excessive 3-fold induction in both NF-κB and CD86, almost like what was observed in the co-culture model where there was a 4-fold increase for NF-κB and 3-fold increase for CD86 (Fig. 3e). These results support our hypothesis on the critical role of reactive astrocytic IFN-γ in dampening the M1 microglia during E. coli K1 meningitis.

We furthermore investigate how IFN-γ worsens the M1 state of microglia during E. coli K1 meningitis by measuring NO and ROS released from living cells and immunostaining against transcriptional markers in microglia (Fig. 3d). Previous studies reported that interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) mediates a TLR3/NK-κB in viral and bacterial infection57 and pre-treatment with the TLR3 agonist regulated innate immune responses in E. coli K1 meningoencephalitis58. In our study, we discovered that E. coli K1 itself can induce IRF3 level in microglia 3.5-fold higher than the control and 4.5-fold with the addition of soluble IFN-γ (Fig. 3f). Besides, another antimicrobial signaling pathway, NLRP3 inflammasome can be activated directly via bacterial components59 or indirectly via NF-kB activation60. Also, it has been shown that phosphorylated form of IRF3 translocates into the nucleus and upregulates the expression of the NLRP361. Our study found that E. coli K1 alone did not significantly activate NLRP3, but co-stimulation of E. coli K1 and IFN-γ increased NLRP3 signal with 4-fold greater than the control (Fig. 3d, f). Previous studies have demonstrated that elevated IFN-γ levels can enhance NLRP3 inflammasome activity, linking it to increased neuroinflammation and disease progression62,63,64. This suggests that in E. coli K1 meningitis, there is an initial upregulation of IRF3/NF-κB signaling followed by further stimulation of NLRP3 expression by reactive astrocytic IFN-γ. Subsequently, we observed an increase in the level of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in a single infection with nearly 2.5-fold and co-stimulation with 4.5-fold greater than the control (Fig. 3g). Different studies demonstrated that microglia are the main source of iNOS during encephalitis65 and their excessive level in the CNS may cause neurodegeneration in age-related diseases. We also found an excessive increase in nitric oxide (NO) as a downstream product of iNOS activation and ROS as evidence of oxidative stress in microglia during co-stimulation of E. coli K1 and IFN-γ (Fig. 3d, h), which indicates detrimental neuroinflammation state in microglia.

Meanwhile, our study found impaired phagocytosis in co-stimulated microglia, evidenced by reduction of tubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 beta (LC3b) and triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2 (TREM-2) markers (Fig. 3d, i). In a single culture of microglia, we found that E. coli K1 alone can inhibit autophagy, and co-stimulation with IFN-γ worsens this dysfunction, evidenced by a 2-fold and 4-fold reduction compared to the control, respectively. We also found a threefold decrease in LC3b signal in the E. coli K1-infected co-culture model. Our results showed that TREM-2 expression declines in the co-stimulation of E. coli K1 and IFN-γ (Fig. 3d, i). This may be attributed to the proteolytic cleavage of the TREM-2 receptor in the extracellular stalk domain, potentially mediated by a disintegrin and metalloproteinase enzyme such66. It has been discovered that TREM-2 has the ability to regulate immune cells to engulf bacteria, and elevation of TREM-2 induces bacterial clearance67. Therefore, the reduction of the TREM-2 signal in the treatment with IFN-γ, as shown in our results, suggested a reduction in microglial phagocytosis. Then, we further validated our hypothesis by measuring the size of E. coli K1 cluster that was engulfed by the microglia (Fig. 3k, j). In the presence of IFN-γ, microglia reduced their ability to clear E. coli K1, evidenced by more than a half reduction of bacterial cluster size. A previous study also found a similar phenomenon in macrophages co-stimulated with LPS and IFN-γ68. This impairment may exacerbate neuroinflammation in microglia, promisingly causing neuronal damage.

E. coli K1 causes neuronal DNA damage, leading to H3K4me3 promoting α-Syn phosphorylated by detrimental neuroinflammation

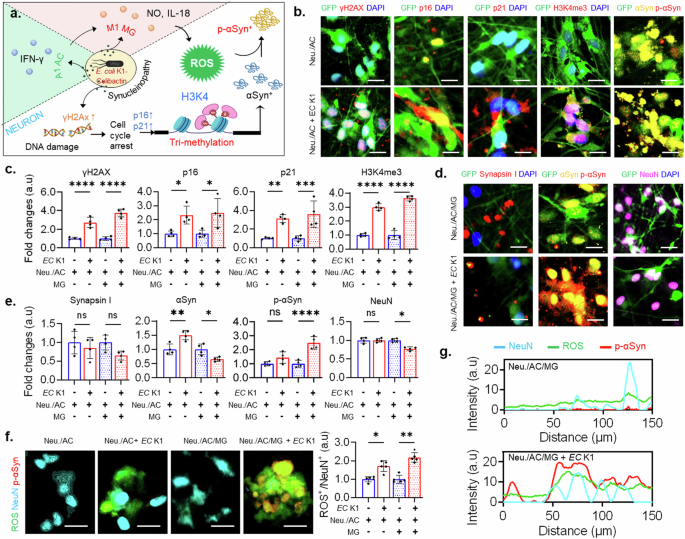

Emerging research in the fields of genomics and epigenetics has uncovered the role of epigenetic modifications in the pathogenesis of NDs69 and microbe-host interaction. Here, we hypothesized that E. coli K1 triggers DNA-DSB in infected neurons due to their genotoxic colibactin, leading to permanent cellular senescence, which is associated with alterations in histone modifications, particularly an increase in H3K4me3 levels, which may lead to aberrant gene expression patterns of SNCA, results in the upregulation of αSyn expression. The accumulation of αSyn in neurons can be post-translational modified by microglial detrimental neuroinflammation that mediates neuronal mitochondrial oxidative stress (Fig. 4a). To validate this possibility, we used a co-culture model of neurons/astrocytes and a tri-culture model of neurons/astrocytes/microglia on chip.

a A signaling of E. coli K1 (EC K1) inducing neurotoxic synucleinopathy. b, d Fluorescent images of neuronal markers in co-culture of neurons/astrocytes (Neu./AC) and tri-culture of neurons/astrocytes/microglia (Neu./AC/MG). c, e Quantification of neuronal markers in co-culture of neurons/astrocytes and tri-culture of neurons/astrocytes/microglia. f Representative images of tri-staining of NeuN/ROS/p-αSyn and quantification of neuronal ROS in co-culture and tri-culture system. g Graphs showing overlapped signals of NeuN, ROS, and p-αSyn. All experiments were repeated four times independently and statistically analyzed by One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey HSD test (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001). All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Scale bars, 50 μm. The full dataset used for Fig. 4 is available in Supplementary Data 4 and 5.

As we expected, the results showed upregulation of DNA-DSB, permanent cell cycle arrest, and epigenetic modification in both E. coli K1-infected co-culture and tri-culture models (Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 6). We found that gamma-H2AX (γ-H2AX), an acute sensor for DNA-DSB, were highly expressed in E. coli K1-infected co-culture and tri-culture with nearly threefold and fourfold greater than the controls, respectively. It has been reported that meningitic E. coli K1 is able to produce genotoxic colibactin that causes DNA damage24,70. As a response to DNA damage, the cells can run a DNA repair process to maintain genomic integrity, but most neurons are in a permanent post-mitotic stage. Therefore, once neurons get DNA damage, it triggers neuronal senescence associated with age-related neurological disorders. The p53-responsive gene p21 has frequently been regarded as essential for initiating cellular senescence, while p16 may play a more significant role in sustaining this phenotypic state. Our study observed high expression levels of senescence hallmarks, both p21, and p16, in infected neurons. Particularly, the p21 marker was increased threefold and 3.5-fold in the E. coli K1-infected co-culture and tri-culture compared to the controls, respectively. Meanwhile, the p16 marker induced nearly 2.5-fold in the infected models. Synchronically, the human brain samples of patients with NDs also harbor an increased proportion of senescent neurons71.

Moreover, we observed significant increases in the level of H3K4me3 markers with threefold and 3.5-fold in the E. coli K1-infected co-culture and tri-culture, respectively, as shown in Fig. 4b, c and Supplementary Fig. 6. Subsequently, we found the increase of αSyn in the infected co-culture model with nearly 1.5-fold greater than the control while the expression of αSyn reduced in the E. coli K1 exposure tri-culture (Fig. 4e). Another research has also indicated that in the brains of individuals with PD, particularly in dopaminergic neurons, there are changes in the levels and distribution of H3K4me3 that are commonly associated with the SNCA promoter, facilitating a more open chromatin structure that allows gene expression72. This elevation ultimately leads to higher levels of αSyn.

Interestingly, in the co-culture model, we did not observe upregulation of p-αSyn, while our results showed 2.5-fold elevation of p-αSyn in the infected tri-culture (Fig. 4d, e). The increase of p-αSyn in the tri-culture further resulted in the mild reduce of synaptic marker (Synapsin I) and neuron marker (NeuN) as shown in Fig. 4d, e, which suggested the critical role of microglial detrimental neuroinflammation in synucleinopathy-associated neurodegeneration during E. coli K1 meningitis. Another study showed that acute meningitis-induced neuroinflammation elevates mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways, including increasing levels of cyto c, and caspase-3, in neurons33. Previously, we observed the same phenomena in the gut EP as the results discussed in Fig. 1. Thus, we validated whether microglial neuroinflammation induces calcium influx and mitochondrial oxidative stress during E. coli K1 meningitis. We found that there was in huge increase in calcium influx (Supplementary Fig. 7) and neuronal ROS (Fig. 4f) in the E. coli K1-infected tri-culture, which was associated with the increase of p-αSyn proved by the overlapped signal of ROS/NeuN/p-αSyn (Fig. 4f, g and Supplementary Fig. 8). Prior researches has demonstrated that the co-localization of cyt c and α-Syn, as well as the incubation of α-Syn with cyt c and hydrogen peroxide, results in the oxidative stress-driven aggregation of α-Syn. This aggregation occurs through the cross-linking of αSyn’s tyrosine residues, forming di-tyrosine bonds73,74.

Consequently, accumulated misfolded proteins may cause long-term autophagy dysfunction and neuroinflammation in microglia. We tested this hypothesis by using LPS and IFN-γ as a stimulator for neuroinflammation and pHrodo-conjugated amyloid-β as a model for misfolded protein in a single culture of microglia cells. We observed the reduction in uptaken amyloid-β, dysfunction of autophagy markers, and increase in inflammatory markers (Supplementary Fig. 9). Taken all together, our study has demonstrated that neuronal epigenetic modification and ROS are critical factors inducing progressing accumulation of p-αSyn in E. coli K1 meningitis.

Discussion

PD is the second leading NDs affecting middle-aged and older adults and is increasing faster than those of any other NDs75. A key pathogenesis of PD is the intraneuronal aggregation of fibrillar αSyn protein translated by the SNCA gene75. Interestingly, pathological αSyn aggregates with prion-like self-propagating activity are present in the duodenum of PD patients76. Moreover, a recent study has found evidence of αSyn aggregates in the gut samples and brain samples of people and mice with IBD77, which has suggested the connection of GBA. While a study reported that patients with IBD are at high risk for meningitis78, several researches have demonstrated the existence of E. coli at the sites of inflammation in the gut of IBD patients79. However, the interconnection among bacterial meningitis, gut inflammation, and synucleinopathy remains unclear. Overall, our study has shown the notion of a complex interplay between E. coli K1 meningitis, systemic inflammation, and synucleinopathy via the GBA.

In the human GI tract, enterendocrine cells are well-known to express αSyn80 in response to bacterial ligands and metabolites81. However, it is possible for non-sensory cells in gut EP to generate αSyn due to their abundant presence in the intestinal lumen and direct contact with gut bacteria. Our results demonstrated that long exposure to E. coli K1 triggered mitochondrial calcium influx, which in turn led to the elevation of ROS and αSyn phosphorylation at serine 129 when compared to the untreated model, which offers insight into how E. coli K1 can induce p-αSyn in gut EP. Moreover, we observed severe inflammation in gut EP upon E. coli K1 infection, which may exacerbate mitochondrial dysfunction and calcium dysregulation, potentially amplifying ROS generation and p-αSyn. Upon crossing the gut barrier, several studies have shown that E. coli K1 is capable of evading detection and phagocytosis by macrophages43, key immune cells tasked with engulfing and eliminating invading pathogens. Also, previous research has demonstrated that chicken macrophages secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, in response to early E. coli K1 infection82. Although IL-6 can enhance the bactericidal activity of macrophages83 and amplify the cell-mediated immune response against E. coli K184, it may contribute to BBB damage. Here, our findings suggest that the dysregulation of IL-6 production during E. coli K1 meningitis can exacerbate BBB disruption, thereby facilitating bacterial invasion into the CNS and contributing to the pathogenesis of meningitis.

Upon encountering E. coli K1, astrocytes rapidly respond to the presence of the bacterium by becoming activated and releasing release pro-inflammatory cytokines. Here, we identified IFN-γ as a crucial early mediator involved in astrocytic immune response upon E. coli K1 infection, exerting both beneficial and neurotoxic effects85. Our results suggest that astrocytic release of IFN-γ can modulate microglial activity, leading to reduced phagocytic capacity and subsequently increased E. coli K1 survival in the CNS. Several studies have shown that IFN-γ signaling in microglia may induce the upregulation of MHC class II and other immune-related molecules, promoting their activation and pro-inflammatory functions86. While this activation is essential for mounting an effective immune response against pathogens, it can also shift microglia towards a more inflammatory phenotype, which may be associated with impaired phagocytosis. This dysregulation may result in inadequate clearance of pathogens and cellular debris, further exacerbating neuroinflammation and neuronal damage.

While the infection of neuronal cells by diverse microbial agents has been documented in numerous viral infections, the invasion of neurons by bacterial pathogens is a comparatively rare occurrence. A recent study found that E. coli K1 is capable of invading hippocampus neurons, which mainly rely on the bacterial IbeA and neuronal contactin-associated protein15, which suggests a possible mechanism of how E. coli K1 may directly induce neuronal damage. Our study elucidated that E. coli K1 meningitis induces a G1/S phase arrest in infected neurons, a critical cell cycle checkpoint that regulates DNA replication and cell division. This arrest is a result of the interaction between host cell signaling pathways and bacterial virulence factors, culminating in the dysregulation of neuronal cell cycle progression. Furthermore, this arrest triggers the aberrant accumulation of αSyn, a protein predominantly found in presynaptic terminals, which plays a central role in PD pathology. The mechanism underlying this accumulation involves histone modifications, specifically the H3K4me3, which alters the chromatin structure and transcriptional regulation of genes associated with αSyn expression. Importantly, our findings revealed that microglial inflammation elevates neuronal ROS, which contributes to the phosphorylation of αSyn, potentially leading to progressive neurodegeneration.

Typically, E. coli K1 meningitis is an acute infectious process with mortality rates ranging from 10% to 15% within the first 3–5 days87. Patients who receive effective treatment during the early stage have a higher chance of survival. However, elevated levels of H3K4me3 and p-αSyn were observed during E. coli K1 meningitis may persist and accumulate over time, even after the acute phase has resolved. The stable epigenetic change of H3K4me3 probably predisposes neurons to increased vulnerability to aging and other stressors in survivors. Meanwhile, the lasting presence of p-αSyn promotes aggregation and may potentially initiate neurodegeneration. In this study, we suggest that early-life infections may act as a first hit, priming the brain for later neurodegeneration via life-long accumulation of p-αSyn. Although our study did not include the blood immune cells, we utilized IL-6 a representative inflammatory cytokine to mimic peripheral inflammation and its contribution to the BBB injury upon E. coli K1 meningitis. While our simplified GBBB model does not fully recapitulate the complex cellular interaction of human BBB due to the lack of astrocytes and pericytes, it allows for the study of E. coli K1-mediated barrier damage in part. In addition, future studies could incorporate with in vivo model and integrate complementary quantitative methods to gain deeper insights into the assessment of oligomeric forms of αSyn and the complex biological mechanisms underlying E. coli K1 meningitis-synucleinopathy as presented in our study.

Conclusions

Our study reveals that E. coli K1-induced meningitis can lead to DNA-DSB in neurons, resulting in permanent cellular senescence. This process is associated with alterations in histone modifications, particularly an increase in H3K4me3 levels, which may lead to aberrant gene expression patterns of SNCA, resulting in the upregulation of αSyn expression–a protein closely linked to the pathogenesis of PD. The αSyn in neurons can be phosphorylated into p-αSyn by neurotoxic microgliosis-inducing ROS. Taking all together, we provide insights into the mechanism of E. coli K1 infection as a potential risk factor for synucleinopathy onset.

Methods

Study design

This study aimed to develop a microphysiological system that mimics the human GBA to investigate systemic inflammation and neuropathogenesis associated with E. coli K1 meningitis. To achieve this, we created a three-compartment microfluidic platform using photolithography and soft lithography, allowing for the culture of five different types of cells spanning the human GBA, including gut epithelial cells (EP), brain endothelial cells (EC), neurons (Neu.), astrocytes (AC), and microglia (MG). The final platform consisted of three GBA microfluidic devices integrated into a glass slide at the bottom and an acrylic array at the top, serving as a medium reservoir (Supplementary Fig. 1c). This design enables three replicates within a single platform, supports long-term cell survival, and facilitates easy imaging. To assess the complex interplay of E. coli K1 infection in gut-blood-brain-barrier damage, a critical aspect of meningitis, we developed a gut-blood-brain-barrier model by co-culturing E. coli K1, gut EP, and brain EC in separate chambers. Then, soluble IL-6 was introduced to the brain EC chamber 24 hours after infecting the gut EP chamber with E. coli K1. This experimental approach was designed to mimic the peripheral immune responses that occur during the progression of bacterial meningitis. Specifically, the delay in IL-6 addition reflects the time-dependent activation of systemic inflammation, where gut-originated infections trigger the release of IL-6 into circulation. These cytokines subsequently contribute to the development of meningitis. Barrier damage was then identified through immunostaining of tight junction proteins. The fluorescent signal was normalized by the non-stimulated group to get fold changes.

To demonstrate detrimental neuroinflammation during E. coli K1 meningitis, we established an immune surveillance model by co-culturing human immortalized astrocytes and microglia in the CNS chamber with or without E. coli K1 infection. Immunostaining against neuroinflammatory markers, along with living cell assays and analysis of multiple cytokines, were utilized to evaluate inflammatory responses during E. coli K1 meningitis. To investigate the role of astrocytic IFN-γ on microglial-mediated neuroinflammation, soluble IFN-γ was introduced into single cultures of microglia 4 hours prior to stimulation with E. coli K1. This pre-treatment period was selected based on evidence that IFN-γ primes microglial activation, facilitating the upregulation of inflammatory signaling pathways and the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. The signals induced by this treatment were subsequently normalized to non-stimulated microglia to account for baseline activation. Next, to evaluate IFN-γ-impaired microglial phagocytosis of E. coli K1 and neurotoxic proteins, we co-cultured E. coli K1 and microglia with pHrodo-Aβ with/without prior stimulation with IFN-γ. Finally, we mimicked the neurons-glia interaction model by tri-culturing hNPC-derived neurons and astrocytes with immortalized microglia in the CNS chamber to identify the role of neuroinflammation in neurodegeneration during E. coli K1 meningitis. We used immunostaining against neurodegenerative markers and other living cell assays to characterize neuropathogenesis associated with E. coli K1 meningitis.

Preparation of Escherichia coli K1

Escherichia coli K1 (ATCC, Cat. 700973) was proliferated in Tryptic Soy Broth (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. 22092-500 G). The culture was placed at 37 °C with shaking at 100 × rpm overnight. The bacterial culture was diluted 100-fold until the optical density at 600 nanometers wavelength attained a value of 1 under identical experimental conditions. Finally, the bacterial pellets were separated from the bacterial conditioned medium by centrifuging at 10,000 × g in 10 min.

Microfluidic chip fabrication

We utilized photolithography to fabricate the SU8 master mold and soft lithography methods to reconstruct a microfluidic platform comprising three chambers for reconstructing multi-organ interaction (Supplementary Fig. 1), by pouring a mixture of 10% (v/v) of polydimethylsiloxane base and 1% (v/v) of curing agent (Sylgard 184 A/B, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) into the master mold. Then, the mixture is vacuumed for 20 min to completely remove all remaining bubbles, followed by curing at 60 °C for at least two hours for polymerization. Next, the PDMS sheets are removed from the mold and punched 2 mm diameter holes to make the inlets and outlets while the medium reservoirs are fabricated by laser cutting the 6 mm thick acrylic sheets (Zing 24, Epilog Laser, Golden CO., USA). Then, the PDMS and acrylics are bonded together by using a mixture of uncured PDMS and curing agents. The assembled platforms were placed at 60 °C for at least 4 hours for full binding. Lastly, the glass slides were bonded with the PDMS using oxygen plasma (PX-250, March Plasma System Petersburg FL, USA) with settings of 350 mW power for 2 min.

Gut epithelial cell preparation

The Caco-2 cell line (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA, Cat. HTB-37), which is derived from human intestinal epithelial cells, was proliferated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium-high glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. D5796-500ML). The cells were proliferated using the medium containing 10% (v/v) of fetal bovine serum from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat. F2442) and 1% (v/v) of Penicillin-Streptomycin (Lonza, Cat. 17-745E). Then, the Caco-2 cells were placed at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until reaching approximately 80% of confluency. The Caco-2 culture medium was exchanged every two days with fresh medium.

Brain endothelial cell preparation

Human immortalized brain endothelial cells (EC) were acquired from Cedarlane Laboratories (Ontario, Canada) and cultured in a T25 flask coated with 1% (v/v) of collagen. The cells were proliferated using the medium containing endothelial cell growth basal medium-2 (Lonza, Cat. 190860), 1% (v/v) of penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. P4333), 1.4 μM hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. H0888-1G), 10 mg/mL L-Ascorbic acid (MedChem, Cat. HY-B0166G), 1% (v/v) of chemically defined lipid concentrate, 10 mM HEPES (Gibco-BRL, Cat. 15630-106), 20 ng/mL bFGF (Stemgent, Cat. 03-2002), and supplement with 5% v/v of FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. F2442). The cells were placed at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until reaching 80% of confluency. The brain endothelial cell culture medium was exchanged every two days with fresh media.

Proliferation of human microglial cells

The immortalized human microglia (SV40 cell line) were purchased from Applied Biological Material Inc. (ABM, Cat. T0251) and were grown in a T25 flask (SPL Life Sciences, Cat. 70012) containing 5 mL of microglial proliferation medium that contained 90% (v/v) of Pigrow III (ABM, Cat. TM003) and 10% v/v of FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. F2442), and 1% (v/v) of penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. P4333). Then, the cells are maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. and the cell culture medium is exchanged every 2 days until it reaches 90% of confluency.

Proliferation of human astrocytes

The immortalized human astrocytes (SV40 cell line) were purchased from Applied Biological Material Inc. (ABM, Cat. T0280) and were grown in a 1% (v/v) of collagen-coated T25 flask (SPL Life Sciences, Cat# 70012) containing 5 mL of microglial proliferation medium that contained 90% (v/v) of Pigrow IV (ABM, Cat. TM004) and 10% (v/v) of FBS (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. F2442), and 1% (v/v) of penicillin-streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. P4333). Then, the cells are maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2. and the cell culture medium is exchanged every 2 days until it reaches 90% of confluency.

Proliferation and differentiation of human neural progenitor cells

Human neural progenitor cells (ReN) were purchased from EMD Millipore (Billerica, MA, US, Cat. SCC008) and cultured in a 1% (v/v) of Matrigel-coated T25 flasks (SPL Life Sciences, Pocheon, Korea, Cat# 70012). The 1% (v/v) of Matrigel coating solution is prepared by adding 10 μL of Matrigel (Corning, Cat# 356235) to 0.99 mL of DPBS (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. D8537). The ReN cells are cultured in a proliferation medium containing DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Cat. 11320033), 0.1% (v/v) of Heparin (2 mg/mL, StemCell Technology, Cat. 7980), 2% (v/v) of B27 (Gibco, Cat. 17504044), and 1% (v/v) of Penicillin/Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. P4333), bFGF (20 ng/ml, Stemgent, Cat. 03-0002) and hEGF (20 ng/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. SRP6253)88. The cells were maintained at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and the cell culture medium was exchanged every 2 days until it reached 90% confluency.

Next, the human neural progenitor cells were differentiated in a differentiation medium containing DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Cat. 11320033), 0.1% (v/v) of Heparin (2 mg/mL, StemCell Technology, Cat. 7980), 2% (v/v) of B27 (Gibco, Cat. 17504044), and 1% (v/v) of Penicillin/Streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. P4333) for 14 days to obtain neurons/astrocytes. The differentiated medium was exchanged every two days with fresh media.

Preparation of human GBA models

We reconstructed the gut-brain platform to study the pathogenesis of E. coli K1 meningitis-inducing systemic inflammation and neuropathogenesis. We coated microfluidic chambers with 10 μL of Poly D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. A-003-M), then placed at RT for 20 min. The CNS chamber was incubated with 1% (v/v) Matrigel solution at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, we loaded 10 μL of ReN cells (108 cells/mL) to the CNS chamber and placed the platform at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 30 min for attachment. Next, we added 100 μL of fresh medium into each reservoir and exchanged every other day for 14 days to get neurons/astrocytes. Prior to gut EPs and brain ECs loading, we coated the gut chamber and BBB chamber with 10 μL of 2 mg/mL collagen Type I at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, we seeded 10 μL of gut EPs (108 cells/mL) and brain ECs (107 cells/mL) to each chambers and placed the platform in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for at least 5 days to get the monolayer of gut EP and brain EC. Two days prior to infection, we added immortalized microglia (105 cells/mL) to the CNS to recreate neuron-glia interaction. After that, we infected E. coli K1 to the gut EP chamber and placed it in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for an additional 2 days (Supplementary Fig. 1d).

The microfluidic devices were maintained under semi-dynamic conditions, enabling passive media to flow through a hydrostatic pressure gradient without requiring an external pump (Supplementary Fig. 1e). This gradient was generated by adding 200 μL of fresh medium to the inlet reservoir and 100 μL to the outlet reservoir of each device. Consequently, media flowed sequentially from the inlet through the main chambers of the gut EP, brain EC, and CNS compartments, as well as the interconnecting microchannels, effectively mimicking the physiological communication between these systems. This setup mimics the physiological communication between these compartments. This passive flow ensured continuous nutrient delivery and waste removal for the culture cells.

Preparation of GBBB models

To create GBBB model, we coated microfluidic chambers with 10 μL of Poly D-lysine (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. A-003-M), incubated at RT for 20 min, and washed with PBS 1X (HanLab, Cat. K19274065). We seeded 10 μL of gut EPs (108 cells/mL) and brain ECs (107 cells/mL) to each chambers and placed the platform in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for at least 5 days to get the monolayer of gut EP and brain EC, then we infected E. coli K1 to the gut EP chamber.

Preparation of central immune surveillance models

To create immune surveillance-on-chip, we coated microfluidic chambers with 1% v/v of Matrigel and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, we loaded 10 μL of immortalized microglia/astrocytes (107 cells/mL) and incubated the devices in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C for 1 hour for cell attachment. Next, we added 100 μL of fresh medium to each reservoir. Prior to infection, we exchanged medium without antibiotics and added E. coli K1 directly to the CNS chamber and incubated in a 5% CO2 cell culture incubator at 37 °C.

Preparation of neuron-glial interaction models

To create neuron-glia interaction-on-chip, we coated microfluidic chambers with we coated microfluidic chambers with 1% v/v of Matrigel and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Afterward, we loaded 10 μL of ReN cells (108 cells/mL) into the CNS chamber and incubated the platforms at 37 °C and 5% CO2 for 1 hour. Finally, we added 100 μL of fresh medium and exchanged every two days for 14 days. Two days prior to infection, we added immortalized microglia to the CNS to recreate neuron-glia interaction. After that, we infected E. coli K1 directly to the CNS chamber and placed at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

Assessment of microglial phagocytosis assay

The microglia SV40 cells were proliferated in a T25 flask until they reached 90% confluency, as described previously. Then, the cells were detached by incubating with Trypsin EDTA (Sigma, Cat. T3924) at 37 °C and 5% O2 for 2–3 min. Then, the cells were harvested by centrifuging at 1300 × rpm in 3 min and placed in a mixture of 1 mL of Diluent C and 2 μL of the green-fluorescent dye (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. PKH67GL). The mixture was then placed at room temperature for 5 min and centrifuged at 1300 × rpm for 3 min. The microglia cells were captured in the FITC channel (Alexa488). The Escherichia coli K1 were grown in Tryptic Soy Broth (Sigma-Aldrich, Cat. 22092-500 G) overnight at 37 °C. Then, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4500 × rpm for 10 min and were promptly resuspended into a dye solution containing 1% (v/v) of BactoView™ Live red dye (Biotium, Cat. 40101-T). The mixture was placed at 37 °C for 30 min in dark, then the cells were harvested by centrifugation and resuspended into growth medium according to experimental purpose. The bacterial cells were captured in the TRITC channel (Alexa 594).

ROS assessment

ROS was assessed by dichlorofluorescein diacetate (H2DCFDA) (ThermoFisher, Cat. D399) according to the provided guidance from the manufacture. Briefly, the cell samples were incubated with fresh medium containing the 5 μM of ROS indicator for 30 min in the dark at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Then, fresh medium was added into the cells to incubate for an additional 30 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Finally, ROS signals were captured using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon TiE microscope, Nikon with FITC channel (Alexa488).

NO assessment

We used DAF-FMTM diacetate (ThermoFisher, Cat. D-23844) to measure NO according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Particularly, the cells were placed with 10 nM DAF-FMTM diacetate in fresh medium at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Then, the NO indicator solution was removed and replaced by fresh medium for an additional incubation at 37 °C with 5% CO2 for 30 min. Lastly, the NO signals were imaged by fluorescence microscope (Nikon TiE microscope, Nikon) with FITC channel (Alexa488).

Multiple cytokines assessment

A multiplex cytokine array kit (R&D Systems, Cat. ARY005) was used to assess the expression of various cytokines and chemokines. Briefly, the cell culture-conditioned medium was harvested and centrifuged to remove the remaining cell pellets. Then, a mixture of conditioned medium and biotinylated detection antibodies was incubated for at least 2 hours while the nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with a blocking buffer. Then, the prepared mixture was added to the blocked nitrocellulose membranes, allowing binding of the target proteins and immobilized capture antibodies. The arrays were placed at 4 °C on a shaker for at least 6 hours and gently washed at least three times at 10-min intervals to remove any unbound antibodies. Chemiluminescent detection solution and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase were used to assess the intensity signal that is proportional to the level of proteins in the conditioned medium. Then, we used ImageJ software (Wayna Rasband, NIH) to quantify the results.

Calcium imaging

The cell samples were incubated with 5 μM of the calcium-sensitive dye Rhod2-AM (Abcam, Cat. 142780) at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min, following the manufacturer’s guidance. Then, the cells were gently washed twice with calcium-free HBSS and imaged using fluorescence microscope in FITC channel. The fluorescence intensity was normalized to the baseline value F0 and reported as the mitochondrial calcium concentration.

Immunostaining

Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Biosesang, Cat. PC2031-100-00) for 30 min, then washed with phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.1% (v/v) of Tween®20 to remove the excessing paraformaldehyde. Next, the fixed cells were treated with 0.1% (v/v) of Triton-X 100 in PBST for 30 min at and blocked with 3% (v/v) of BSA for 1 hour. Primary antibodies were diluted to an appropriate concentration and treated to the samples overnight at 4 °C (as detailed in Supplementary Table 1). Subsequently, the samples were treated with secondary antibodies diluted 1:200 and DAPI for 2 hours. Finally, the samples were washed five times with PBST before imaging using Nikon fluorescence microscope. The intensity of immune reactivity was quantified with ImageJ software (Wayna Rasband, NIH).

Statistical analysis

All the data were relatively normalized by the control group and reported as mean ± standard deviation. The number of replicates was provided in the description of figure captions. The statistical differences between were analyzed by unpaired t-test and One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test using SPSS software (IBM, NY, US). P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The symbols NS, *, **, and *** denoted no significance, p value < 0.05, p value < 0.01, p value < 0.001, and p value < 0.0001 respectively.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Responses