Evaluating large language models in analysing classroom dialogue

Introduction

Learning happens during human interactions1, and classroom dialogue is one of the fundamental ways to initiate such interactions in formal schooling according to social-cultural perspectives. Compared with other modal of interactions, language plays a significant role in the development of thinking. Classroom dialogue has thus been an essential focus of academic enquiry for decades, recognised as pivotal in the process of creating meaning and thereby fundamental to the educational experience (ref. 2, p. 3). Empirical studies have revealed the benefits of teaching dialogic skills to students, noting enhancements in their reasoning abilities and collaborative problem-solving capabilities1,3,4,5,6. Dialogic pedagogy, inherently participatory, aims to validate and expand all participants’ contributions in classroom dialogues7. Its primary goal is to cultivate learner autonomy, encouraging students to collaboratively seek understanding, build upon their ideas, and integrate others’ views to refine their thought processes (ref. 8, p.3). Evidence also points to academic improvements in various subjects as a direct outcome of dialogic pedagogical approaches9,10,11,12. Notably, a UK-based efficacy trial involving nearly 5000 students reported moderately robust results13. This trial, focusing on Dialogic Teaching for children aged 9–10, demonstrated a positive impact on their performance in English, science, and mathematics, roughly equating to an additional two months of academic progress.

Despite the established qualitative methods traditionally used in analyzing classroom dialogue, such as content, discourse, and thematic analysis, challenges remain in the efficiency and objectivity of these approaches. The typical workflow of dialogue analysis involves transcription, coding, and interpretation. Transcription, the conversion of spoken words in recorded classrooms into text, has been expedited by software, significantly reducing time and human resource demands. However, the subsequent coding process presents a more formidable hurdle, both in terms of complexity and time expenditure.

Coding, the act of sorting and structuring data into categories based on themes, concepts, or emergent significant elements, is indispensable in qualitative research. This method enables a systematic dissection of voluminous data, such as interview transcripts or observational records, which defy straightforward quantification. The coding process entails delving into the data to unearth distinct concepts and patterns, ultimately leading to the formation of themes that encapsulate the core of the data. This aspect of qualitative research, especially in educational domains where data can be particularly intricate, is marked by an iterative and adaptable approach. Unlike its quantitative counterpart, which aims to numerically represent data, qualitative coding embraces the researcher’s subjectivity and the contextual nuance of the data.

This subjective dimension, however, introduces potential complications in educational research. The researcher’s inherent biases and viewpoints may colour their interpretation, potentially leading to skewed outcomes. Furthermore, the labour-intensive and resource-heavy nature of coding in qualitative educational research poses challenges, particularly when handling extensive datasets or conducting long-term studies. Ensuring the reliability and validity of coded qualitative data, especially in the diverse and variable contexts of educational research, remains a complex and demanding endeavour.

In the ever-evolving domain of educational technology, the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has marked a significant milestone in shaping learning outcomes. At the vanguard of these AI, advancements are large language models (LLMs), which epitomise cutting-edge capabilities in natural language processing (NLP), a key component in educational interactions14. The profound ability of LLMs to process and interpret verbal exchanges in educational settings has been recently underscored by Brown and colleagues14, highlighting their potential in transforming traditional educational methodologies.

LLMs, such as GPT-4, have demonstrated their capacity to detect patterns and trends within educational interactions, categorising and synthesising dialogue data effectively. This ability paves the way for large-scale qualitative analysis, a feat previously daunting due to the limitations of conventional research methods. The current study is thus poised to evaluate how generative AI can be strategically employed in the educational field, leveraging these advanced models to gain deeper insights into learning processes.

With a particular focus on classroom dialogue, this research seeks to explore the role of LLMs in understanding and enhancing communication and interaction within educational contexts. The choice of classroom dialogue as a case study is deliberate, considering the centrality of communication in the learning experience. By harnessing the capabilities of LLMs, this study aims to offer a novel perspective on the analysis of educational discourse, contributing to the broader narrative of how AI, particularly generative AI, can revolutionise educational research and practice. This exploration not only aligns with the contemporary trend of digital integration in education but also opens new avenues for personalised and effective learning strategies, tailored to the unique needs of diverse educational landscapes.

Large language models (LLMs) represent a class of highly sophisticated AI tools primarily designed for tasks involving natural language processing14,15. These models have revolutionised the approach to understanding and generating human language through advanced computational methods.

LLMs possess several fundamental capabilities. First of all, LLMs are adept at comprehending complex language constructs, enabling them to grasp context, infer meaning, and understand subtleties and nuances in language16. Their proficiency extends to understanding idiomatic expressions and detecting sentiment, making them versatile in various linguistic analyses. Secondly, these models excel in generating coherent, contextually appropriate, and often creative text outputs. They are used in applications ranging from content creation to conversation agents15. Their ability to produce text that closely mimics human writing has significant implications for fields like journalism, creative writing, and customer service. Last but not least, LLMs are known for their exceptional pattern recognition abilities. They can identify and learn from patterns in data, a capability that is fundamental to tasks such as language translation, summarisation, and even predictive text generation14. In general, LLMs’ fundamental capabilities including natural language understanding, natural language generation and pattern recognition.

In terms of the mechanism of LLMs, they are trained on extensive and diverse datasets, which include a wide array of text sources like books, articles, and websites17. This training involves processing billions of words and requires sophisticated algorithms to manage and learn from such a vast amount of data. The training of LLMs involves deep learning techniques, particularly transformer models, which have shown remarkable efficiency in handling sequential data like text18. These models learn to predict and generate language by identifying patterns and relationships within the training data. The diverse training allows these models to handle a wide range of language tasks and adapt to different styles, dialects, and jargon. This adaptability is crucial for applications that require a nuanced understanding of language19.

Based on the introduced capabilities and mechanism of LLMs, a standout feature of LLMs is their ability to contextualise information, enabling them to provide more accurate and relevant responses in conversational AI or content generation16. Therefore, the advent of LLMs like GPT-4 signifies a major leap forward in AI’s language capabilities. They offer transformative potential across numerous sectors, from education and customer service to content creation and beyond14.

In addition to these references, recent studies have explored the application of AI in classroom discourse analysis. For instance, Suresh et al.20 presented the TalkMoves dataset, which includes annotated K-12 mathematics lesson transcripts focusing on teacher and student discursive moves. Hunkins et al.21 investigated teacher analytics to uncover discourse that affects student motivation, identity, and belonging in classrooms. Jensen et al.22 applied deep transfer learning to model teacher discourse, demonstrating the potential of AI to capture and analyze complex educational interactions. Alic et al.23 developed methods to computationally identify funneling and focusing questions in classroom discourse. These studies underscore the growing interest and significant advancements in applying AI to educational dialogue analysis, providing a robust foundation for the present study.

GPT-4, or generative pre-trained transformer 4, is the latest iteration in the GPT series developed by OpenAI. It represents a significant leap forward in the capabilities of large language models (LLMs) for natural language processing tasks. Building on the advancements of its predecessors, GPT-4 is distinguished by its larger size, improved training algorithms, and enhanced capacity to understand context and generate human-like text24. Additionally, the model finds diverse applications ranging from creating content, answering queries, language translation, and even coding, showcasing a remarkable breadth of knowledge and adaptability.

In recent advancements within the realm of artificial intelligence, OpenAI has introduced a novel and innovative concept titled “My GPTs,” a significant extension of their existing generative pre-trained transformer (GPT) series. This new development, as outlined by OpenAI24, represents a transformative step in democratising AI technology by enabling users to create and customise their own versions of the ChatGPT model for specific applications, ranging from everyday tasks to specialised professional uses. The core of “My GPTs” lies in its user-friendly interface, which allows individuals to build personalised AI models without any prerequisite coding skills. This feature not only broadens the accessibility of AI technology but also fosters a more inclusive approach towards its development and utilisation.

The “My GPTs” concept aligns with OpenAI’s broader vision of integrating AI into real-world applications. Developers are provided with the capability to define custom actions for their GPTs, enabling these models to interact with external data sources or APIs, thereby enhancing their real-world applicability. This advancement signifies a major leap in the evolution of AI as ‘agents’ capable of performing tangible tasks within various domains24.

In conclusion, OpenAI’s “My GPTs” marks a significant milestone in the journey towards accessible, customisable, and safe AI, fostering a community-driven approach to AI development and application. This initiative not only expands the horizons of AI technology but also invites a diverse range of users to actively participate in shaping the future of AI, resonating with OpenAI’s mission to build AI that is beneficial to humanity24. In this study, a GPTs is developed based on the coding rules for analysing classroom dialogue.

Classroom dialogue has been heavily researched in recent years due to its perceived role in student learning (e.g. refs. 6,25,26,27). Influenced by socio-cultural perspectives, authors in this field view learning as a social activity, mediated through dialogue. Specifically, dialogue is perceived as the intermediary between collective and individual thinking28. Its quality, therefore, becomes particularly important as it determines the quality of collective thinking and, through this, individual progress. These views have resulted in research which aims to identify forms of dialogue that promote higher-order thinking and, thus, are optimal for learning. Thanks to this research, there is now a fair degree of consensus over which forms are especially productive29. The characteristics of optimal classroom dialogue proposed by Alexander25 have proved particularly influential. According to Alexander, classroom dialogue should be: (1) collective, with participants reaching a shared understanding of a task; (2) reciprocal, with ideas shared among participants; (3) supportive, with participants encouraging each other to contribute and valuing all contributions; (4) cumulative, guiding participants towards extending and establishing links within their understanding; and (5) purposeful, that is directed towards specific goals. Similar forms of dialogue have been highlighted in the context of student–student interaction. Littleton and Mercer29 have identified three types of student–student talk: disputational, cumulative and exploratory. Characterised by disagreement and individualised decisions, disputational talk was thought to be the least educationally productive. Some educational value was attributed to cumulative talk, as it was characterised by general acceptance of ideas, but a lack of critical evaluation. Exploratory talk was observed less frequently; yet, it was regarded as the most educationally effective. It involved participants engaging critically with ideas and attempting to reach a consensus. Initiatives, like the ‘Thinking Together’ programme30,31, aimed to promote primary school children’s use of exploratory talk, and showed a positive impact on students’ problem solving, mathematics and science attainment/learning. Likewise, ‘accountable talk’ has been promoted as the most academically productive classroom talk32. It encompasses accountability to (1) the learning community, through listening to others, building on their ideas and expanding propositions; (2) accepted standards of reasoning (RE), through emphasis on connections and reasonable conclusions; and (3) knowledge, with talk that is based on facts, texts or other publicly accessible information and challenged when there is lack of such evidence.

In developing our coding scheme, we drew heavily on the work of Hennessy et al.33, who provided a comprehensive framework for analyzing classroom dialogue across various educational contexts. Their coding scheme, developed through extensive empirical research, offers a robust structure for categorising the diverse forms of interaction observed in classroom settings. Additionally, the book by Kershner et al.34 on research methods for educational dialogue was instrumental in guiding our methodological approach, offering insights into the practical applications and implications of dialogue analysis in educational research.

Working in secondary classrooms, Nystrand et al.35 characterised dialogic instruction via three key discourse moves that teachers might make: (1) authentic questions, which are questions with no predetermined answers; (2) uptake, which occurs when previous answers are incorporated into subsequent questions; and (3) high-level evaluation, which occurs when teachers elaborate or ask follow-up questions in response to students’ replies, instead of giving a simple evaluation, such as ‘Good’ or ‘OK’7. While there are differences between these approaches, there are also marked commonalities, regardless of whether the research refers to whole-class or small-group contexts. Shared features include:

-

invitations that provoke thoughtful responses (e.g. authentic questions, asking for clarifications and explanations);

-

extended contributions that may include justifications and explanations;

-

critical engagement with ideas, challenging and building on them;

-

links and connections;

-

attempts to reach a consensus by resolving discrepancies.

For these features to occur, a generally participative ethos is important, with participants respecting and listening to all ideas. This necessitates making the discourse norms accessible to all32. Changing the classroom culture in this manner might be a challenge for any teacher. For better analysing classroom dialogues, researchers proposed various coding schemes, in this study, we employed the coding scheme conducted by Cambridge Educational Dialogue Research Group, and revised it considering the context of Chinese classrooms. Table 1 shows the codes and their brief definitions.

Specifically, in this coding scheme, the elaboration invitations (ELI) and reasoning invitations (REI) categories captured authentic questions that provoked thoughtful answers (e.g. ref. 35). The elaboration (EL), RE and Querying (Q) categories captured core features of exploratory talk (e.g. ref. 29) and accountable talk32; namely building on ideas, justifying and challenging, respectively. The co-ordination invitations (CI) category addressed invitations to synthesise ideas, while simple co-ordination (SC) and reasoned co-ordination (RC) addressed responses to such invitations, the difference between RC and SC being that RC draws on evidence, theory or a mechanism for justification36,37. Establishing links and identifying connections, stressed by Alexander25 and Michaels, O’Connor, and Resnick32, were represented by the reference back (RB) and reference to wider context (RW) categories, which focus respectively on prior knowledge or beliefs and the wider context. Two further codes are not directly mappable to current conceptions of productive dialogue: agreement (A) and other Invitations (OI). Nevertheless, in combination with ELI or EL, A represents high-level evaluation7. Nystrand et al.7 highlight ‘simple evaluation plus elaboration’ and ‘simple evaluation plus follow-up question’ as high-level teacher evaluations of student responses. In our coding system, the first example is captured through the combination of A and EL and the second through the combination of A and ELI. As for OI, this category was included to contrast ELI, REI and CI with less productive invitations.

Results

Time efficiency evaluation

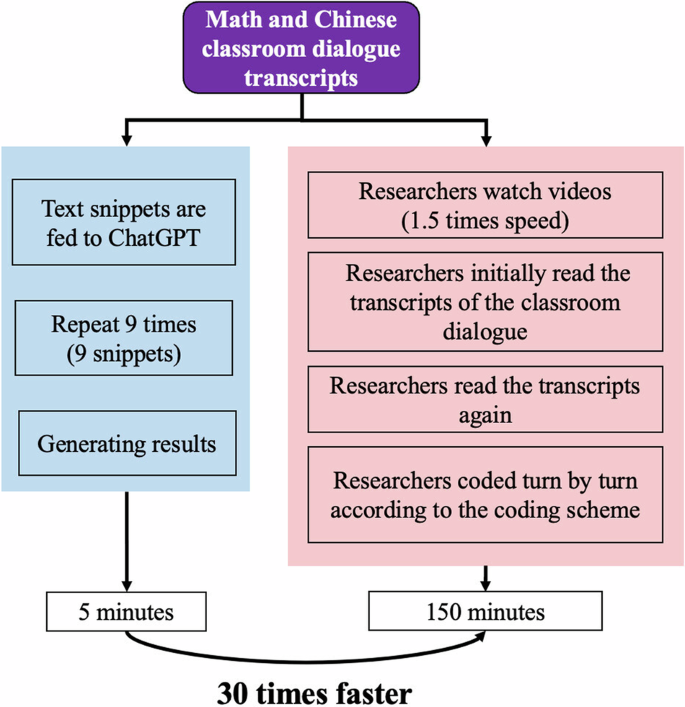

For the analysed Chinese lessons, the cumulative duration was ~4 h and 7 min, while for the Math lessons, it was about 5 h and 17 min. Utilising ChatGPT, and excluding instances where dialogue turns exceeded the input limitations for the AI, the total time spent on analysis did not exceed one hour. To calculate the time savings compared to manual coding, we selected a single Math lesson for a timed comparison. This lesson, lasting 41 min and 29 s with 82 dialogue turns, was processed by ChatGPT in increments of ten dialogue turns to avoid skipping, totalling 5 min of analysis time. The manual coding process involved an experienced researcher watching the lesson video at 1.5x speed, reviewing the transcript twice, and coding each dialogue turn based on context, taking ~2.5 h.

Therefore, compared to manual coding, ChatGPT afforded a time-saving factor of ~30 times (150 min for manual coding versus 5 min for ChatGPT, see Fig. 1). It is noteworthy that this result is based on the performance of an experienced researcher, who minimised the need to frequently consult the coding rules. In scenarios where researchers are less acquainted with the referred coding scheme, manual coding would likely take even longer. This substantial time efficiency offered by ChatGPT emphasises its potential to significantly expedite the coding process in educational research, aligning with findings from previous studies that highlight the efficiency of AI in data analysis tasks38,39.

This figure illustrates the process and time efficiency of two methods for analysing classroom dialogue transcripts from math and Chinese classes. The light blue panel describes the automated method using ChatGPT, where text snippets are fed to ChatGPT and the process is repeated nine times with nine snippets, generating results in ~5 min. The light pink panel describes the manual method, where researchers watch videos at 1.5 times the speed, initially read the transcripts, read them again, and then code each turn according to the coding scheme. This manual process takes ~150 min. The automated method is shown to be 30 times faster than the manual method.

The consistency evaluation between the human coder and ChatGPT

To evaluate the consistency between human researchers and ChatGPT, we conducted an inter-coder reliability analysis. According to Richards40, inter-coder reliability “ensures that you yourself are reliably interpreting a code in the same way across time, or that you can rely on your colleagues to use it in the same way.” This measure assesses the extent to which independent coders agree upon the application of codes to content, thereby ensuring reliability and validity in qualitative analysis41. For each dialogue turn of analysis, one tallies the number of agreements (where both coders assign the same code) and divides by the total number of dialogue turns to yield a percentage. This figure provides a sense of the coding alignment. However, to adjust for chance agreement, researchers often supplement this with Cohen’s Kappa statistic, which offers a more conservative estimate of coder consistency42.

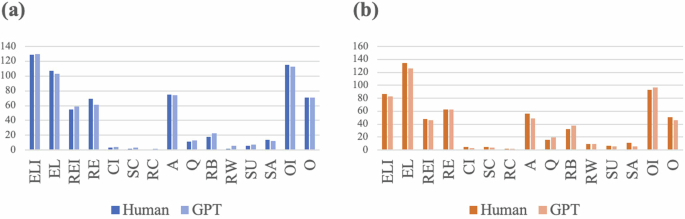

Figure 2 displays the coding outcomes of classroom dialogue analysis in math and Chinese lessons, revealing the frequencies of the 15 codes the researcher and ChatGPT coded. In Math classroom analysis, over six lessons with 576 dialogue turns, the inter-coder agreement percentage between the human coder and ChatGPT is reported at 90.37%. Similarly, in Chinese classroom analysis, which encompasses six lessons with 348 dialogue turns, the agreement percentage is slightly higher at 90.91%. The figure suggests a high level of consistency, indicating that ChatGPT can effectively mirror human coding practices to a significant extent.

This bar chart represents the frequencies of each code analysed by human researchers and ChatGPT. a Displays the analysis for maths classroom dialogue, where darker blue bars represent the results analysed by human coders and lighter blue bars represent results from ChatGPT. b Shows the analysis for Chinese classroom dialogue, with darker orange bars representing human coders’ analysis results and lighter orange bars representing results from ChatGPT.

In the context of coding classroom dialogue for educational research, Cohen’s Kappa statistic serves as a critical measure for evaluating inter-coder reliability, surpassing mere percentage agreement by accounting for chance agreement42. According to Table 2, the Kappa statistics for Chinese and math lessons reveal varied levels of coder concordance. While there is no universally accepted standard for interpreting Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, a consensus has emerged in the literature regarding its interpretation. This consensus categorises the Kappa values as follows: slight (0.00 to 0.20), fair (0.21 to 0.40), moderate (0.41 to 0.60), substantial (0.61 to 0.80) and almost perfect (0.81 to 1.00)42,43. Accordingly, this study adopts these widely recognised benchmarks to analyze the inter-coder reliability presented in Table 2. This approach aligns our analysis with the established norms in the field, ensuring that our interpretations of the Kappa values are both consistent and comparable with existing literature. High Kappa values, as seen in codes such as ELI (0.973 for Chinese, 0.995 for Math) and EL (0.961 for Chinese, 0.977 for Math), indicate near-perfect agreement, underscoring the potential of ChatGPT to accurately follow the coding scheme. Conversely, lower Kappa scores, such as CI (0.497 for Chinese, −0.005 for Math) and SC (0.216 for Chinese, 0.004 for Math), point to a divergence in understanding or application of the coding manual, necessitating further enquiry into these discrepancies. Particularly concerning are the negative Kappa values in RC for Chinese (−0.002) and Math (0.004), which suggest no agreement beyond chance and highlight areas where the AI’s coding decisions substantially differ from the human coder. These results prompt a crucial discussion on the refinement of AI coding algorithms for enhanced alignment with human coding practices in educational settings.

Discussion

The research substantially illustrates the prospects and feasibility of large-scale automated assessment in educational contexts through comprehensive evaluations of time efficiency in manual versus automated coding processes, and calculations of consistency between these methodologies. This examination not only underscores the potential for efficiency improvements but also lays a foundational understanding for the automation of complex tasks. Nevertheless, alongside these promising insights, the study also reveals several points meriting further investigation.

The analysis revealed differences in GPT’s performance between Chinese and math lessons for certain categories such as CI, SC, RW and SU. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is the inherent difference in dialogue complexity and contextual nuances between the two subjects. Chinese lessons often involve more narrative and descriptive language, which may be easier for GPT to interpret and categorise correctly. In contrast, math lessons frequently involve technical and procedural language, which can be more challenging for the model to interpret accurately without additional contextual understanding.

Furthermore, the nature of interactions in Chinese lessons typically includes more extended discussions and elaborations, providing a clearer context for the model to analyze. Math lessons, on the other hand, often involve shorter, more direct exchanges focused on problem-solving and instruction, which may not provide as much context for the model to work with. This difference in dialogue style and content could contribute to the observed performance variations.

Lower consistency between human researchers and ChatGPT in codes like CI (Co-ordination Invitation), SC (Simple Co-ordination), and RC (Reasoned Co-ordination) can be attributed to differences in contextual interpretation. ChatGPT primarily analyzes textual information and explicit cues, whereas human coders consider the broader context and implicit meanings44. Furthermore, the complexity and subjectivity of these codes impact inter-coder consistency. Co-ordination, involving multiple interlocutors, requires analyzing various factors and subtle dialogue nuances, challenging for automated coding45.

Table 3 exemplifies differing coding results. A human coder might code Turn 4 as CI, based on context, recognising the teacher’s consideration of prior student contributions. Consequently, another student’s response in Turn 5 is coded as RC for providing insights with reasons. In contrast, ChatGPT’s analysis of Turns 4 and 5 relies more on individual utterances and keywords. Phrases like ‘how do you think,’ not explicitly inviting elaboration or reasoning, lead to an OI (Other Invitations) code. Similarly, the presence of ‘because’ in Turn 5 results in a RE (Reasoning) code by ChatGPT.

Previous studies utilising specialised intelligence have achieved notable results. For instance, ref. 46 reported ~80% inter-coder agreement using a seven-category coding framework. Specialised intelligence, which prevailed before 2017, relied on data-driven machine learning to automatically learn knowledge from labelled data of specific tasks, storing this knowledge in small model parameters. However, the limitations of specialised intelligence include its dependency on task-specific labelled data, high labelling costs, and the inability to address tasks not covered by the labelled data.

With the advancement of technology, our study leveraged general intelligence, specifically the foundation model (GPT-4 in this study), which employs self-supervised training methods to automatically learn knowledge from vast amounts of unlabelled data across general domains, storing this knowledge in large model parameters. The advantages of general intelligence are evident in the cost-effectiveness and near-unlimited availability of unlabelled data, as well as the robust support large models provide for learning and storing knowledge.

Our study employed a 15-category coding scheme and achieved over 90% inter-coder agreement, surpassing the results of specialised intelligence. This demonstrates an improvement in coding accuracy and consistency, highlighting the advancements in AI capabilities. The superior performance of GPT-4 underscores its potential in educational research, particularly in handling complex tasks and large amounts of narrative data, thereby advancing the field beyond the limitations of specialised intelligence.

Despite the study’s coverage of major subjects like math and Chinese and the inclusion of different contexts of classroom activities such as introduction, practice, and review, the sample size and scope remain limited. A more comprehensive validation across a broader spectrum of disciplines, age groups, and collaborative learning environments is necessary to ensure the generalisability of the findings.

The variation in interaction frequency across different subjects is a significant factor. For instance, research shows that subjects like mathematics often involve more problem-solving and individual work, leading to less frequent but more targeted interactions47. In contrast, subjects like language arts tend to encourage more continuous and exploratory dialogues48. While in our research, there are less dialogue turns in Chinese lessons comparing to math ones, further investigation on the feature of classroom dialogue in the same subject under different contexts also can be an interesting topic for future research. Age-related differences in student expressiveness also play a crucial role in dialogue and interaction patterns. Younger students may have less sophisticated communication skills, affecting the nature and complexity of classroom dialogues31. As students mature, their ability to engage in more complex and abstract discussions evolves, leading to a shift in the balance of various dialogue types and coding sequences. Furthermore, the learning environment itself significantly influences interaction modes. Collaborative settings often promote more distributed and peer-focused interactions, contrasting with more teacher-centric dialogues in traditional settings49. These variations were not fully represented in our sample.

Therefore, while our study provides valuable insights into classroom interactions, the limitations in sample diversity suggest caution in the broad application of our findings. Future research should aim to include a wider range of subjects, age groups, and learning environments to capture the full spectrum of interaction dynamics in educational settings.

In conclusion, this study underscores the transformative potential of LLMs, particularly GPT-4, in the qualitative analysis of classroom dialogues. The research reveals a significant reduction in the time required for dialogue analysis, demonstrating the efficiency and practicality of AI in educational settings. The high level of consistency between GPT-4 and human coders in most coding categories suggests that AI can effectively mirror human coding practices. This study represents a crucial step towards scalable qualitative educational diagnosis and assessment, offering a promising direction for future research in educational technology. Future work should aim to address the limitations observed, expanding the scope to a broader range of subjects, age groups, and learning environments. This will ensure a more comprehensive understanding and application of AI in educational research, potentially revolutionising the analysis of classroom interactions and informing teaching practices.

Methods

Data

In this study, we harness diverse datasets to evaluate the efficacy and applicability of AI, particularly GPT-4, in educational settings. Our data sources include dialogue transcripts in Chinese classes and manual and automated coding results. These data provide insights into the patterns and effectiveness of classroom dialogue.

The study adhered to Chinese law and the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, with approval granted by the institutional review board (IRB) of the Department of Psychology at Tsinghua University (#2017-8). Informed consent forms were distributed in paper format and signed by all volunteer participants and their legal guardians prior to data collection.

The data for this study were collected from a middle school, involving classroom dialogues across mathematics and Chinese classes. Audio and video recordings of the classroom interactions were made, capturing both teacher-student and student–student dialogues. The recordings were transcribed into text to facilitate detailed analysis.

The first dataset comprises classroom dialogue transcripts, which are crucial in understanding real-world educational interactions. These classroom dialogues are sourced from a high school in Beijing and encompass two main subjects and educational levels. The classroom dialogue recordings were automatically transcribed by a software named Lark into texts and then manually checked by research assistants. The richness and diversity of these texts allow for a comprehensive analysis of how AI can be integrated into classroom dialogues effectively.

To ensure the quality and relevance of our analysis, a significant portion of our data has undergone meticulous manual coding. This dataset includes classroom dialogues and interactions that have been annotated by education professionals. Annotations has been done based on the coding scheme and rules. This manual coding serves as a benchmark for assessing the accuracy and contextual appropriateness of AI-generated responses and analyses.

The third dataset involves the application of GPT-4 and the customised GPTs for coding and analyzing classroom dialogues. This cutting-edge AI model offers insights into the potential of machine learning in educational contexts. We specifically focus on how GPT-4 interprets educational dialogues, its effectiveness in identifying key educational elements, and its capability to generate meaningful and contextually relevant responses. By comparing the GPT-4 coding with manual annotations, we aim to evaluate the practicality and reliability of AI in educational settings, potentially paving the way for AI-assisted educational tools.

Participants

The study involved students from two classes, one each from the first and second grades of junior high school, at a middle school in Beijing. Along with these students, their mathematics and Chinese language teachers also participated in the experiment. This selection of participants was strategic, aiming to provide a diverse range of perspectives and experiences in the classroom setting.

In both the mathematics and Chinese language subjects, six lessons from each were meticulously selected for this study. These lessons were chosen based on their representativeness of the typical curriculum and their potential to generate rich, meaningful dialogue for analysis. The aim was to ensure a broad spectrum of classroom interactions were captured, encompassing various teaching styles, student responses, and interactive dialogues.

For each of these subjects, the chosen lessons underwent a detailed process of annotation. This process was twofold: one, a manual annotation performed by experts in classroom dialogues, and two, an automatic annotation carried out by the customised GPTs specifically designed for analyzing classroom dialogues. The manual annotation served as a benchmark, a standard against which the GPTs’ performance could be measured.

The volume of data collected for this experiment was substantial, exceeding 150,000 characters. This extensive dataset was crucial for providing a comprehensive analysis. The length of the data ensured that a wide range of classroom interactions were included, allowing for a more thorough and nuanced examination of the AI’s capabilities in interpreting and analyzing educational dialogues.

The inclusion of both mathematics and Chinese language subjects was particularly significant. It allowed the experiment to explore the AI’s versatility in handling different types of academic content—the numerical and problem-solving focus of mathematics and the linguistic and interpretative nature of the Chinese language. This diversity in subject matter was expected to provide deeper insights into AI’s adaptability and effectiveness across varying academic disciplines.

Overall, the participation of students and teachers from these specific classes, along with the careful selection of lessons and extensive data collection, set the stage for a robust and insightful exploration into the use of AI in analyzing educational dialogues.

Procedures

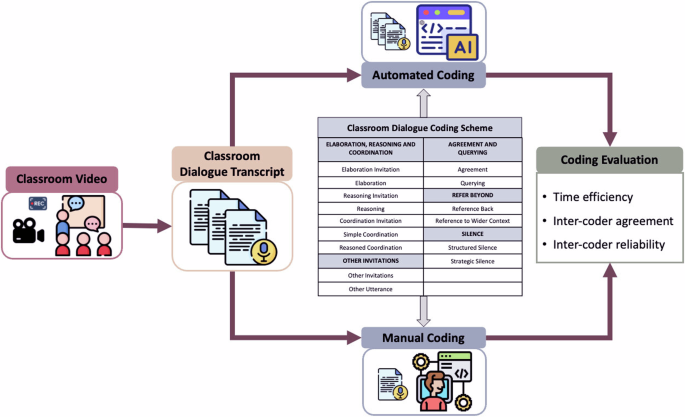

Figure 3 presents the technological roadmap utilised in our study, illustrating a comprehensive workflow from initial data acquisition to the final comparative analysis. The flowchart commences with the collection of classroom video recordings, which are then transcribed into text. Both manual and GPT-driven annotations are applied following the same predetermined coding scheme, with the manual process serving as a benchmark for the AI’s performance. The GPT model, tailored to these specific educational analysis tasks, annotates the dialogues autonomously, paralleling the manual effort. The culmination of this methodology is a critical comparative analysis, juxtaposing the manual annotations with those generated by the GPT model. The roadmap encapsulates the systematic approach adopted in our study, reflecting the meticulous integration of AI tools like GPT-4 with conventional methods to evaluate and enhance the analysis of educational dialogues.

This figure illustrates the technology roadmap for coding classroom dialogue. The process begins with classroom video recording, then the videos are transcribed into classroom dialogue transcripts. The transcripts are simultaneously coded using two coding methods: automated coding using AI (ChatGPT) and manual coding by human researchers. Both methods apply the Classroom Dialogue Coding Scheme, which includes 15 categories. The coding results are then evaluated based on time efficiency, inter-coder agreement, and inter-coder reliability. Note: Icons in this figure are made by Flaticon: https://www.flaticon.com/.

The video tapes of classroom dialogues need to be transcribed into text for analysis. Following a thorough evaluation of various automated transcription solutions, Lark was chosen, attributing to its exemplary features. The standout capability of Lark is its provision of time stamps, a critical attribute for aligning the transcribed text with precise instances within the video recordings. This functionality significantly enhances the ease of playback and systematic organisation of the data. Furthermore, Lark supports the identification and attribution of dialogue to specific speakers and offers facilities for post-transcription modifications, which proved immensely beneficial for our research objectives. The granularity and precision of transcription afforded by Lark were indispensable for the accurate analysis and subsequent interpretation of the interactions observed in the classroom settings.

Once the transcription was complete, the next step involved meticulously organising the transcribed text. We manually transferred the transcript into Excel spreadsheets for better data management. In these spreadsheets, each dialogue turn was separately identified and formatted uniformly. This organisation was critical to ensure consistency and ease of access for subsequent analysis stages. The structured format helped in segregating and identifying distinct conversational elements, laying a clear foundation for both manual and AI-driven annotations.

The manual coding process was conducted based on a predefined coding scheme (see Table 1). Every dialogue turn in the classroom conversations was encoded by educational experts. This meticulous process involved scrutinising each dialogue turn to categorise and code them according to the established coding rules. The manual coding served as a gold standard, offering a comprehensive and nuanced understanding of the classroom dynamics.

To evaluate the coding scheme, inter-human-rater reliability was assessed using interrater reliability calculations. According to O’Connor and Joffe50, interrater reliability can enhance ‘the systematicity, communicability, and transparency of the coding process,’ thereby providing credibility to the scheme. Hence, Cohen’s Kappa (κ) was used to address the consistency of coding system implementation51. As suggested by statistical guidelines, the data for interrater reliability should constitute at least one-tenth of the total dataset. Therefore, one classroom dialogue transcript was selected, and the selected transcripts were independently coded by both experts.

For reliability assessment using Cohen’s Kappa (κ), each code was examined in each line for presence (1) or absence (0), and the assessment was conducted using SPSS 21.0. According to Landis and Koch43, if the value of κ is less than 0.5, the consistency of the coding scheme needs further discussion. Based on the assessment results, Codes RC, Q and OI were refined and discussed between the two coders to resolve disagreements. The final reliability assessment results are presented in Table 4. This metric ensured the consistency of the coding process, making the annotations reliable and reproducible.

To enable automatic coding in our custom-developed system, we integrated the GPT-4.0 API. Utilising retrieval-augmented generation (RAG), we vectorized the classroom dialogue analysis scheme (CDAS) and fed these knowledge vectors into GPT-4, equipping the system with professional-level dialogue coding capabilities. Additionally, we embedded a finely tuned prompt engineering mechanism to facilitate automatic dialogue coding. Here we provided an example of a GPT prompt:

When a teacher’s turn tends to invite building on, elaboration, evaluation, or clarification of their own or another’s contribution:

Includes:

-

Asking participants to critique, evaluate, comment on, compare, agree or disagree with another’s contribution or idea. If these questions ask students to complete mathematical calculations, they should be coded as OI (see OI category).

Does not include:

-

Cases where the coder has no access to the ideas or work being addressed, because these are not visible or audible.

-

Procedural questions that could be built on previous contributions.

Output: ELI

The final step involved a comparative analysis between the manual coding and those results generated by the GPT model. Three important dimensions are considered in the evaluation: efficiency, inter-coder agreement, and inter-coder reliability. Time efficiency in this context refers to the duration required to complete the coding process, comparing the speed of human coders against the GPT-based automatic coding system. The operational algorithm includes defining tasks, measuring duration, repeating measurements, and analyzing data. While there is no complex formula, it can be represented simply as:

The inter-coder agreement here refers to the degree of agreement or consistency between human coders and the GPT-based coding on the same dataset. The operational algorithm includes standardising the coding scheme, independent coding, collecting and comparing codes, and calculating the agreement ratio. The percentage agreement is calculated as:

Inter-coder reliability in this context measures the consistency of coding outcomes between human coders and the GPT system across different datasets or coding instances, taking into account the possibility of chance agreement. The operational algorithm includes ensuring a consistent coding scheme, performing independent coding, calculating reliability coefficients, and analyzing and interpreting results. Inter-coder reliability, particularly when comparing human to automated coding, can be assessed using Cohen’s Kappa (κ), and the formula is shown below:

*Here, Po is the relative observed agreement among raters, and Pe is the hypothetical probability of chance agreement.

Data analysis

A comprehensive examination was conducted focusing on three distinct yet interconnected aspects: the assessment of time savings provided by using GPTs for classroom dialogue coding, the inter-coder agreement percentage and inter-coder reliability between human coders and ChatGPT.

The time efficiency brought about by the use of GPTs in coding was a critical aspect of our analysis. By comparing the duration of manual coding tasks with those completed using GPTs, we could discern the practical benefits of AI in educational research. This aspect is pivotal, particularly in academic settings where efficient time management directly translates to enhanced productivity and resource optimisation. The analysis revealed significant time savings when employing GPTs, suggesting a substantial impact on operational efficiency in educational research settings.

We then analysed the inter-coder agreement. This step is crucial for validating the reliability of AI-assisted coding against human standards. We computed the percentage of agreement and the inter-coder reliability using Cohen’s Kappa statistic, which is a widely recognised measure in research for its ability to account for chance agreement. This metric was particularly important to gauge the level of consistency between human coders and ChatGPT, ensuring that the coding of AI aligns accurately with the predefined coding manual. The use of SPSS software enabled a thorough cross-tabulation, facilitating a nuanced understanding of how well ChatGPT’s coding decisions matched with those of human coders.

In summary, our data analysis provided a two-faceted evaluation of AI’s role in coding classroom dialogue. It highlighted not only the technological efficiency of AI in mirroring human coding accuracy but also underscored the practical time-saving benefits. This comprehensive approach ensures a balanced assessment, catering to both the methodological rigour required in qualitative research and the pragmatic needs of educational practitioners.

Responses