Exploring Clec9a in dendritic cell-based tumor immunotherapy for molecular insights and therapeutic potentials

Introduction

Despite advancements in conventional tumor therapies, their efficacy remains suboptimal in clinical practice. Conventional therapeutic approaches, including surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy, often offer limited efficacy, cause significant adverse effects, and are prone to relapse1. The emergence of resistance to conventional tumor therapies poses a pervasive challenge, as tumor cells can adapt and become more aggressive, thereby diminishing treatment effectiveness. Furthermore, systemic toxicity, particularly with chemotherapy, limits the safe dosage that can be administered, impacting overall patient well-being. In recent years, the field of cancer immunotherapies has seen substantial growth, driven by their significant therapeutic effects2,3,4. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a substantial number of tumor immunotherapy drugs, highlighting the expanding landscape of these treatments. Additionally, numerous promising drug candidates are undergoing clinical trials. Tumor immunotherapies are designed to activate the immune system, particularly by enhancing T-cell responses. This is achieved through various strategies, including tumor vaccines, bispecific T-cell engagers (BiTEs), immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), and adoptive cell therapies (ACTs)1,5,6,7. ICIs are a breakthrough in cancer treatment. However, the clinical response rate to ICIs is still low, and less than 20% of patients benefit from ICIs8. BiTEs and ACTs have shown promising therapeutic effects in hematological malignancies but are difficult to apply to the treatment of solid tumors and may induce off-target effects or cytokine release syndrome9. Tumor vaccines, particularly those targeting neoantigens in combination with immune checkpoint blockade, have demonstrated enhanced T cell dynamics and the potential to remodel the tumor microenvironment, reversing its immunosuppressive state and promoting immune cell infiltration10,11. Currently, the FDA has approved three therapeutic cancer vaccines: Sipuleucel-T for prostate cancer12, BCG (Bacillus Calmette–Guérin) for bladder cancer13,14,15, and Talimogene laherparepvec for melanoma16,17. Additionally, four prophylactic vaccines have been approved: Gardasil18,19, Gardasil 920, and Cervarix19,21 for HPV, which can lead to cervical cancer, and a vaccine for HBV22, known to cause liver cancer. While tumor vaccines are pivotal in the fight against cancer, their clinical utility is often constrained by weak immunogenicity, immune tolerance, and off-target effects, and they have not yielded the anticipated efficacy in patients23,24,25.

The dendritic cells (DCs) are the professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) with the strongest antigen-presenting ability, with DCs being the only APCs that can activate naïve CD8+ T cells26,27,28,29. Recent studies have further highlighted their central role in coordinating both innate and adaptive immune responses, emphasizing their critical function in the induction of antitumor immunity30,31. DCs are comprised of plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) and conventional DCs (cDCs), each playing distinct roles within immune responses32,33,34. Specifically, pDCs are renowned for their high cytokine secretion in response to viral stimuli35. The cDCs are classified into non-migratory and migratory types, based on their migratory capabilities and gene expression profiles. The non-migratory types include cDC1s and cDC2s36,37. cDC2 represents a heterogeneous subset, which is mainly found in blood, lymphoid, and nonlymphoid tissues, expressing SIRPα (CD172a) in both humans and mice. Additionally, CD1c is expressed in humans and CD11b in mice. The markers expressed by cDC2s are location-dependent, such as CD1a in the skin and CD103 in the intestine. Among the factors influencing cDC2 differentiation, IRF4 is an important transcription factor for cDC2 differentiation, essential for their development, migration to lymph nodes, and promoting Th2 induction. In mice, additional factors such as PU.1, RelB, and recombining binding protein suppressor of hairless (RBP/J) regulate cDC2 differentiation, while in humans, it is regulated by IRF836,37. cDC2s are recognized for their heterogeneity and capacity to process and present antigens via major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II, contributing to diverse T helper cell responses and the induction/expansion of regulatory T cells38,39. Moreover, recent findings suggest that in humans, the division of labor between cDC1 and cDC2 subsets is less distinct than in mice, with both subsets capable of influencing a range of immune responses38. Additionally, cDC2s exhibit innate plasticity, capable of inducing Th1, Th2, and Th17 responses, and play a regulatory role in the immune system by promoting the formation of intestinal regulatory T cells and regulating liver tolerance34,38,40.

The essence of DC-based tumor vaccines is to enhance the antigen-presentation capacity of DCs and induce an effective CTL response. The cDC1 subset is proficient at antigen cross-presentation and is used for vaccine design to induce CTL responses39. Mouse cDC1 (XCR1+CD8+ or CD103+) and human cDC1 (CD141+/BCCA3+) subsets, characterized by their unique capacity to cross-present exogenous antigens to CD8+ T cells, are pivotal for the development of DC-based tumor vaccines. Although human cDC1 shares functional similarities with mouse cDC1s in this capacity41,42, seminal studies43 suggest that human cDC1s may not be as exclusively specialized in cross-presentation as their mouse counterparts.

C-type lectin receptors such as DEC-205, Clec9a, and Clec12a are abundantly expressed on DCs and are key targets for antigen delivery. In mice, DEC-205 is limited to cDC1 and cDC244,45, whereas in humans, it is expressed in various DC subsets46. Clec9a is consistently expressed on cDC1 in both species, making it an effective target for eliciting CD8+ T cell responses. In contrast, Clec12a typically marks cDC2 in mice, reflecting the receptor’s functional diversity in antigen presentation and immune modulation47. In reviewing the antigen-presenting capabilities of Clec9a, DEC-205, and Clec12a, it is observed that Clec9a and DEC-205 are both highly effective at presenting antigens and activating CD8+ T cells. In contrast, Clec12a shows comparatively weaker antigen-presenting abilities40,45,48. Clec9a plays a critical role in antigen uptake by sensing dead cells. Antigens are cross-presented by DCs, a process where exogenous antigens are presented on MHC class I, leading to the activation of CD8+ T cells49,50,51,52,53. Targeting Clec9a with antigens can induce strong humoral and cellular immune responses49,51,54,55,56,57,58,59. Moreover, targeting antigens to DCIR2 has been explored for its ability to drive immune responses in a way that complements DEC-205 targeting. Studies have shown that DCIR2 targeting can lead to strong CD4+ T cell activation but is less effective than DEC-205 in cross-presenting antigens to CD8+ T cells, thus influencing the balance of immune activation pathways45,60. In contrast, Fc receptors (FcRs), including FcγRs, on DCs add another dimension by facilitating antibody-mediated antigen uptake. The FcR pathway offers flexibility, enabling either immune tolerance or activation depending on the antigen context and delivery method, making it a versatile approach for enhancing DC-targeted therapies40,61.

Antigen-targeted Clec9a has the potential to break immune tolerance and can induce CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses after recognizing antigens62. However, its ability to either induce tolerance or prime immune responses is highly dependent on the context, such as antigen dose and the presence of co-stimulation62,63. At low doses and without co-stimulation, Clec9a may lead to immune tolerance, whereas higher doses with necessary immune co-stimulation can prime effective immune responses52,63. Antigen-targeted DEC-205 may induce immune tolerance, particularly in the absence of additional immune stimulatory signals54. Clec9a expression is restricted to cDC1 subsets including CD8α+ cDC1s and CD103+ cDC1s in mice47,51, and CD141+ cDC1s in humans50. Clec9a is exclusively expressed on cDC1s and efficiently mediates antigen presentation, making it a targeted choice for tumor vaccine delivery. Targeting Clec9a specifically delivers antigens to cDC1s, preventing widespread distribution to all potential professional and nonprofessional APCs in the body, thereby preventing the random activation of other immune cells49. Therefore, delivering a tumor vaccine targeting Clec9a is expected to solve the problems of off-target effects and immune tolerance in developing a tumor vaccine.

This review focuses on recent progress in DC-based tumor vaccines, with an emphasis on the role of Clec9a. The unique ability of Clec9a to enhance antigen cross-presentation and activate CTLs makes it a promising target in cancer immunotherapy. This review aims to summarize the molecular characteristics of Clec9a, its role in DC function and T cell activation, and the prospects and challenges of Clec9a as a target for tumor vaccine delivery.

Molecular characterization, expression, signaling mechanisms, and functional activation of Clec9a

The role of Clec9a in immune function is underscored by its distinct molecular structure, selective expression on DCs, and unique ligand-binding properties. Clec9a+ cDC1s can be generated in both murine and human models, providing a platform to study its role as an endocytic receptor. Through activation of the immunoreceptor tyrosine-based activation motif (ITAM)-spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) signaling pathway, Clec9a promotes downstream immune responses that drive robust antitumor immunity.

Characterization of Clec9a

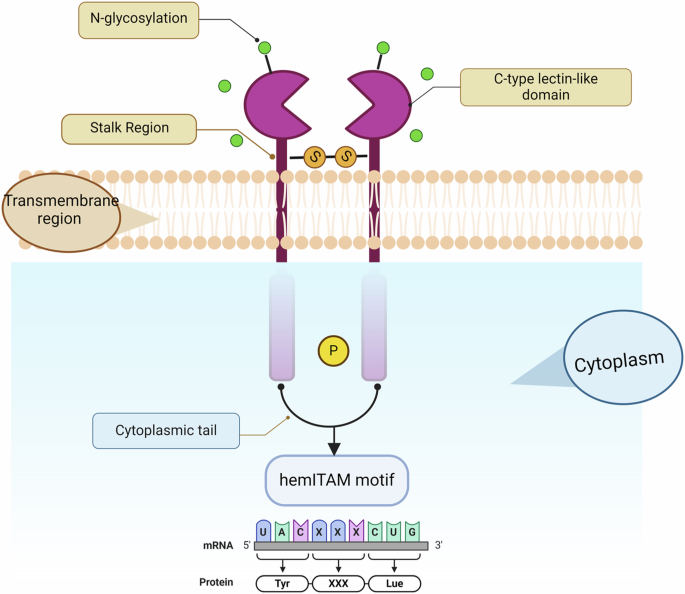

The mouse Clec9a gene consists of seven exons spanning 13.4 kb and encodes a type II transmembrane protein comprising 264 amino acids51,64. The Clec9a protein in mice has three distinct regions: an extracellular C-type lectin-like domain (CTLD), a transmembrane region, and a cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 1)51. The CTLD is characterized by six conserved cysteine residues that are likely involved in intrachain disulfide bond formation, a feature common to CTLDs65. Notably, the CTLD lacks the Ca2+-coordinating amino acid residues typically found in carbohydrate-recognition domains. The CTLD connects to a stalk region containing a conserved cysteine, presumably playing a role in dimerization49. Murine Clec9a also has an additional N-glycosylation site, which distinguishes it from its human counterpart by one cysteine residue in the stalk region, and a neck region comprising seven exons compared to six exons in humans49,51,64. The molecular mass of Clec9a in mice is predicted to be ~30 kDa, and it likely exists as a dimer stabilized by a disulfide bond involving the conserved cysteine in the stalk region (Table 1). Structurally, the mouse Clec9a protein shares 53% identity with the human Clec9a protein, with most structural features, including intracellular signaling motifs, being similar49. Emerging studies in mouse models have highlighted the key role of Clec9a in antigen processing in cDC1s, particularly in extracting and presenting antigens from dead cells to CD8+ T cells. This involves Clec9a-mediated signaling that facilitates antigens into the MHC class I pathway, crucial for antiviral and antitumor responses. These findings offer new insights into the function of Clec9a in immune surveillance and its potential in cancer immunotherapy and vaccine development66. The unique structure of the CTLD in murine Clec9a suggests specialized ligand interactions, particularly in the context of antigen uptake and presentation. The structure is crucial for Clec9a’s ability to recognize and process specific antigens, facilitating efficient cross-presentation to T cells62,67.

The extracellular C-type lectin-like domain (CTLD) is extensively glycosylated, as indicated by the green circles; the neck region serves as a junction between the CTLD and the transmembrane domain; and the intracellular cytoplasmic tail harbors potential signaling motifs, including a hemITAM motif, which is crucial for downstream signaling pathways. Created with BioRender.com (Agreement number: WE26UDX16L).

In contrast, human Clec9a is encoded by 6 exons spanning 12.9 kb, resulting in a 241 amino acid glycosylated dimeric protein (Fig. 1)50,51. Human Clec9a possesses unique sites for glycosaminoglycans and slightly different cysteine configurations25,49. In the clinical context, variations in Clec9a expression or loss could impact its efficacy in antigen presentation and subsequent immune response, a factor that may have implications for cancer prognosis and responsiveness to immunotherapies62. Understanding these correlations could guide personalized therapeutic approaches in oncology, particularly in treatments that target or utilize the functionalities of Clec9a.

Expression of Clec9a is restricted to cDC1s

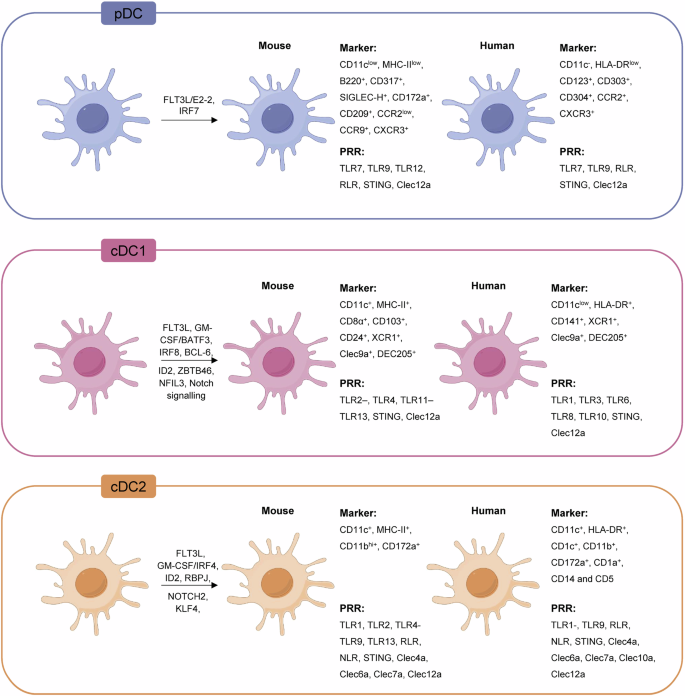

Clec9a in mice is predominantly expressed in the spleen, lymph nodes, and thymus. The pDCs, characterized by their BDCA2+ and CD123+ phenotypes, are primarily found in human blood and lymphoid tissues68 and are crucial for the interferon (IFN) responses (Fig. 2). Recent studies have also elucidated the migration pathways of DCs and monocytes involved in antigen presentation69. While migratory DCs primarily use CCR7 to navigate toward lymph nodes, monocytes that lack CCR7 employ CCR5 to respond to chemokine signals. CCL5 is secreted by DCs and attracts CCR5-expressing monocytes, facilitating their migration to sites of inflammation or lymphoid tissues70 and playing a key role in coordinating antigen transport and DC-mediated immunity71. Clec9a is mainly restricted to CD8α+ cDC1s, with limited expression in pDCs. Clec9a expression is notably absent in other immune cell types, such as B cells, T cells, NK cells, NKT cells, monocytes, macrophages, and granulocytes52,72. In vitro studies have demonstrated that Clec9a is absent in mouse bone marrow-derived DCs (BMDC) cultured with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 4 (IL-4). However, it is prominently expressed in the DC subset induced by mouse fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 ligand (mFlt3L), which primarily comprises cDC1s49.

The figure illustrates the three primary subsets of DCs based on development, phenotype, and function in both mouse and human models: pDCs, cDC1s, and cDC2s. Each subset is detailed with specific markers and transcription factors, emphasizing the restricted expression of Clec9a on the cDC1 subset, a key feature in antitumor immunity. Created with Figdraw.com.

In humans, Clec9a is prominently expressed in the spleen, thymus, and brain. It shows restricted expression on CD141+ cDC1s, a subset of CD14+CD16– monocytes50, and CD24+ DCs in human blood73. The presence of Clec9a in the brain provides potential as a therapeutic target for treating neuroinflammation-based diseases, microbe-induced encephalitis, and brain tumors (gliomas)74. However, its practical application in the brain is constrained by the blood-brain barrier75, underscoring the need for novel drug delivery systems. CD8α+ cDC1s in mice and CD141+ cDC1s in human express high levels of Clec9a, which is instrumental in T-cell activation and antigen cross-presentation47,76,77,78. Conversely, cDC2s, dermal and epidermal DCs, and Langerhans cells do not express Clec9a, highlighting its specificity to cDC79,80. In both species, Clec9a is co-expressed with X-C motif chemokine receptor 1 (XCR1), which binds its unique ligand XCL1, along with Nectin-like molecule 2 and Toll-like receptor 3 (TLR3), which are highly restricted to Clec9a+CD141+ cDC1s in humans81,82,83.

The differentiation of CD8+ cDC1s and CD141+ cDC1s depends on transcription factors, including IRF8, Id2, and Batf376,77,78,79,84. Notably, the absence of Batf3 impairs the cross-presentation function of CD8α+ cDC1s, compromising the immune system’s ability to respond to tumors and viral infections76. This has been demonstrated in Batf3−/− mice, which show a lack of response to ICIs80,81. In addition, Flt3L and Notch signaling play critical roles in the differentiation of Clec9a+ cDC1s, with Flt3L also supporting their expansion both in vitro and in vivo (Fig. 2)82,83,85,86. Additionally, research by Gu et al. revealed that cancer patients with higher levels of CD141+ cDC1s tend to have better prognoses, which are capable of inducing a superior Th1 response and cross-presenting tumor antigens, suggesting that vaccines targeting Clec9a and delivering CD141+ cDC1s could constitute a viable strategy, especially for lung cancer treatment87. Moreover, recent studies in human multiple myeloma patients have shown that Clec9a+ cDC1s are key markers of T-cell infiltration in tumor biopsies, thereby enhancing our understanding of the involvement of Clec9a in cancer88. The proximity of these DCs to TCF1+ T cells is indicative of the disease state and risk status, highlighting the crucial role of Clec9a+ cDC1s in modulating T-cell infiltration and tumor immune dynamics88. Targeting Clec9a in vaccine strategies, especially for conditions such as lung cancer, could amplify T-cell infiltration and alter the tumor immune microenvironment, enhancing therapeutic outcomes.

The ligand of Clec9a

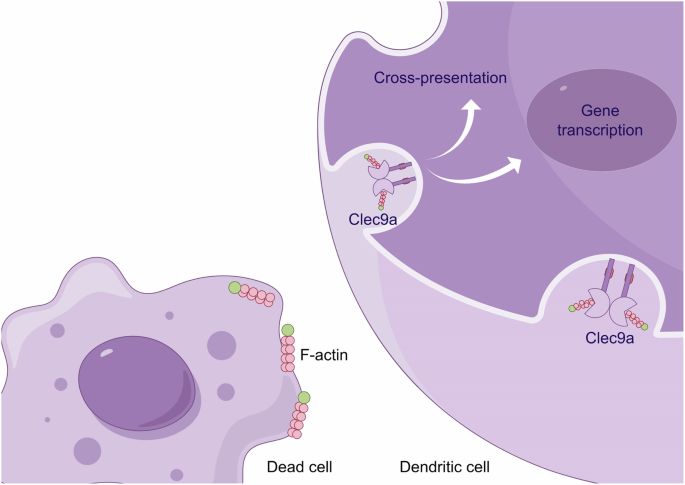

Pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) of immune cells sense infections and tissue damage through pathogen-associated molecular patterns and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), encompassing Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and C-type lectin receptors (CLRs)89,90,91,92,93. As a member of the CLR family, Clec9a is hypothesized to be a PRR for DAMPs. The ectodomains of both mouse and human Clec9a bind to all dead nucleated cells, including those from mice, humans, or even cell lines such as Chinese hamster ovary, African green monkey (Vero), or insect (SF21) cells. However, they do not bind to bacteria or yeast94. This binding extends to nonnucleated cells, including apoptotic mouse platelets and erythrocytes94. Notably, the CTLD of Clec9a binds to damaged or dead cells, with the neck region being crucial in antigen uptake and subsequent internalization into the endocytic pathway (Fig. 3)95.

This finding demonstrated the role of Clec9a in recognizing F-actin structures exposed on the surface of dead cells. Upon recognition of F-actin, Clec9a initiates a signaling cascade that ultimately participates in two critical immunological processes: cross-presentation of antigens and activation of gene transcription. Created with Figdraw.com.

The recognition and binding of actin filaments (F-actin) from damaged or dead cells by Clec9a94 play a pivotal role in the immune system’s ability to manage cellular debris and facilitate cross-presentation of antigens. F-actin, a critical component of the cytoskeleton, is abundant and highly conserved in eukaryotic cells. It becomes exposed upon cell damage or death due to the loss of membrane integrity96,97,98. Clec9a+ cDC1s recognize and bind to F-actin, leading to the activation of Syk and promoting the cross-presentation of antigens96,99. Notably, the loss of Clec9a’s affinity for F-actin significantly impairs this process, demonstrating the importance of this interaction in the immune response64,67. Clec9a does not activate DCs upon binding to damaged or dead cells; instead, it diverts these cells into a recycling endosomal compartment, enhancing the cross-presentation pathway59. This finding indicates a sophisticated mechanism by which Clec9a selectively routes cellular debris to optimize immune processing rather than triggering immediate immune activation.

At the molecular level, the CTLD of Clec9a exhibits a specific binding interaction with F-actin. This interaction is characterized by a 1:1 stoichiometry, where each CTLD binds helically to three subunits of F-actin. Detailed interactions have been mapped, showing that three discrete surface regions of the CTLD engage with three distinct actin subdomains from different F-actin subunits. The most extensive interactions occur with actin subunits 1 and 2, with a notably weaker interaction with actin subunit 364,91. A set of sixteen interacting residues between Clec9a and F-actin was identified, thirteen of which are conserved between the mouse and human versions of the protein. The key residues include W141, E153, W155, and W250 in mouse Clec9a and W131 and W227 in human Clec9a, which are crucial for the stability of this interaction. Among these, W155, W250, and K251 play dominant roles in mediating contact with actin subunit 2, highlighting the specificity of this molecular interaction64. The presence and condition of F-actin, including its decoration with actin-binding proteins, can influence the efficiency of Clec9a binding. For example, the presence of myosin II significantly enhances Clec9a’s ability to bind to F-actin. Conversely, myosin II-deficient impairs the ability of Clec9a+ cDC1s to cross-present dead cell-associated antigens to CD8+ T cells, highlighting the functional importance of these interactions in immune response modulation100.

Generation of mouse and human Clec9a+ cDC1s

The efficiency of generating Clec9a+ cDC1s is crucial for advancing DC-based tumor therapies. In mice, Clec9a+ cDC1s can be generated by culturing BM cells in the presence of mFlt3L49. The use of Flt3L for culturing BM cells to produce various DC subsets such as cDC1, cDC2, and pDCs is widely reported to necessitate a differentiation period of 9–10 days101, with partial medium changes every 4 days49. Moreover, GM-CSF-based protocols provide an alternative approach whereby BMDCs are cultivated over a span of 7–10 days, depending on the desired maturity and the use of additional maturation agents like lipopolysaccharide101. Additionally, the innovative HoxB8-Flt3L culture system exemplifies a scalable method for DC production that permits controlled differentiation. This system allows researchers to initiate differentiation by modulating environmental factors such as cytokine concentrations and estrogen withdrawal, offering flexibility in the timing and expansion of DC populations101. Additionally, in vivo expansion of Clec9a+ cDC1s can be achieved through mFlt3L injection or by inoculation with Flt3L-expressing B16 melanoma cells102,103.

Compared with mouse-derived Clec9a+ cDC1s, human-derived Clec9a+ cDC1s are more difficult to obtain and are fewer in number. A culture system was established to generate human CD141+ cDC1s from adult peripheral blood monocytes. This process begins with the isolation of CD14+ monocytes from peripheral blood mononuclear cells. The monocytes are then cultured in the presence of human GM-CSF (hGM-CSF) and IL-4 for 8 days. CD141+ cDC1s are identified as cells adhering to the culture plate, with increased expression of CD141+ cDC1s and partial expression of Clec9a observed after 3 additional days of culture104. This method results in the effective uptake of dead cells by the generated CD141+ cDC1s. Another study employed a humanized mouse model in which human Flt3L (hFlt3L) treatment generated CD141+ and CD1c+ DCs in vivo86. These human DC subsets phenotypically and functionally resemble their counterparts in human blood. The generated CD141+ cDC1s expressed Clec9a, XCR1, CADM1, and TLR3 but not TLR4 or TLR986. The recent study by Lutz et al. highlights the potential of CD34+ hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) derived from cord blood (CB), BM, or peripheral blood. This approach utilizes OP9 stromal cells to facilitate the differentiation of CD34+ cells into various DC subsets. Key cytokines, such as Flt3L, are crucial for driving the development of cDCs (cDC1, cDC2, and cDC3) as well as pDCs. Additionally, the inclusion of stem cell factor (SCF) enhances the proliferation and expansion of progenitor cells. These controlled conditions ensure the efficient generation of specific DC subsets for further analysis101.

Moreover, Balan et al. reported a protocol for generating XCR1+ (CD11clowCD141highHLA-DR+) and XCR1− (CD11chighCD141+/−HLA-DR+) hDCs from CD34+ progenitor cultures (CD34-DCs)105. During the amplification phase, CD34+ cells were cultured with hFlt3L, hSCF, hIL-3, and hIL-6 in 6-well plates for 7 days. In the differentiation stage, these expanded cells were further cultured with hFlt3L, hSCF, hGM-CSF, and hIL-4 in U-bottom 96-well plates for 8–13 days, with half of the medium being refreshed every 6 days105. Gene expression profiling, phenotypic characterization, and functional analysis demonstrated that XCR–CD34– DCs were similar to moDCs, whereas XCR1+CD34− DCs resembled XCR1+ blood DCs105. Additionally, they reported another culture system to simultaneously generate human pDCs, cDC1s, and cDC2s from CB and non-mobilized CD34+ progenitors82. The CD34+ cells are purified from human CB and expanded with hFlt3L, hSCF, hTPO, hIL-7, or hGM-CSF for 7 days. Subsequently, the expanded cells are differentiated on OP9, OP9_DLL1, or OP9+OP9_DLL1 feeder layer cells, with hFlt3L, hTPO, and hIL-7 for 14–21 days. Half of the medium is replaced with fresh medium supplemented with cytokines on days 7 and 14 of differentiation. Phenotypic, functional, and single-cell RNA sequencing analyses have demonstrated that cell characteristics are strongly homologous to those of blood DCs82.

Moreover, researchers have developed an innovative approach to generate cDC1s from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). First, to generate hematopoietic progenitor cells, iPSCs are co-cultured with OP9 stromal cells for approximately 13 days. Second, CD34+ cells are isolated and co-cultured with OP9-DL1 cells, which express the Notch ligand delta-like 1, along with cytokines such as GM-CSF, Flt3L, and SCF, to obtain cDC1s106. Human iPSCs are cultured in a six-well plate for 7 days. Then, they are harvested and placed on a gelatin pre-coated OP9 over-confluent culture in αMEM (day 0). On day 1, the medium is replaced with fresh medium, and half medium was replaced with fresh medium on days 4, 6, 8, and 11. On day 13, the colonies is digested with collagenase type IV and trypsin. Stromal cells are removed using OP9 medium and a filter. CD34+ cells are isolated using a selection kit and placed on gelatin pre-coated OP9 or OP9-DL1 cells. The cells are cultured by hGM-CSF, hFlt3L, and hSCF-containing αMEM medium for 14 days. The phenotype, genomic and transcriptomic signatures, and function of human iPSC-derived DCs are similar to those of peripheral blood cDC1s. In addition, Makino et al. reported that human iPSC-derived DC differentiation requires Notch signaling106. The generation methods and characteristics of mouse and human Clec9a+ cDC1s are summarized in Table 2.

Clec9a is an endocytic receptor

Clec9a, a member of the C-type lectin family, serves as an endocytic receptor that plays a vital role in antigen processing and presentation within the immune system49. Unlike certain lectins, Clec9a does not mediate phagocytosis50; however, it is crucial for directing bound antibodies and antigens into the endocytic pathway49. This function is particularly important in cDC1s, where Clec9a facilitates the internalization and routing of antigens into the endosome/lysosomal pathway for processing and presentation49,50,51,96. Clec9a+ cDC1s play a key role in this context by recognizing danger signals exposed on necrotic cells. Although Clec9a is not required for the uptake of necrotic material, it is essential for the cross-presentation of dead cell-associated antigens, initiating innate immune responses53. This process is pivotal for immune surveillance and the body’s response to pathological conditions such as cancer. Recent studies by Canton et al. revealed that Clec9a-Syk signaling is instrumental in promoting the cross-presentation of dead cell-associated antigens. This mechanism induces phagosomal membrane rupture upon ligand binding to Clec9a, leading to the release of phagosomal contents into the cytosol and subsequent presentation via MHC I molecules. The activation of its signaling domain triggers Syk and NADPH oxidase, which collectively facilitate phagosomal damage107. Moreover, targeting Clec9a enhances endocytosis in FL-DCs, as evidenced by increased internalization of streptavidin-PE and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-Clec9a mAbs compared to controls. This effect is observed at both 4 °C and 37 °C, indicating a role for Clec9a in facilitating endocytic processes in Clec9a+ cDC1s. Furthermore, the absence of Clec9a in DCs from Clec9a-knockout mice results in reduced internalization of streptavidin-PE-conjugated peptide, underscoring the importance of Clec9a in promoting endocytosis108.

The endocytic capabilities of Clec9a highlight its significance in the immune system, especially in cancer immunotherapy contexts. By mediating the uptake of tumor antigens and presenting them for T-cell activation, Clec9a emerges as a crucial player in the initiation and modulation of antitumor immune responses. Enhancing the immunogenicity of tumor vaccines by harnessing Clec9a, as discussed in recent advances in immunotherapy research, exemplifies the potential of this receptor for developing effective cancer treatments109.

Activation of the ITAM-Syk signaling pathway by Clec9a

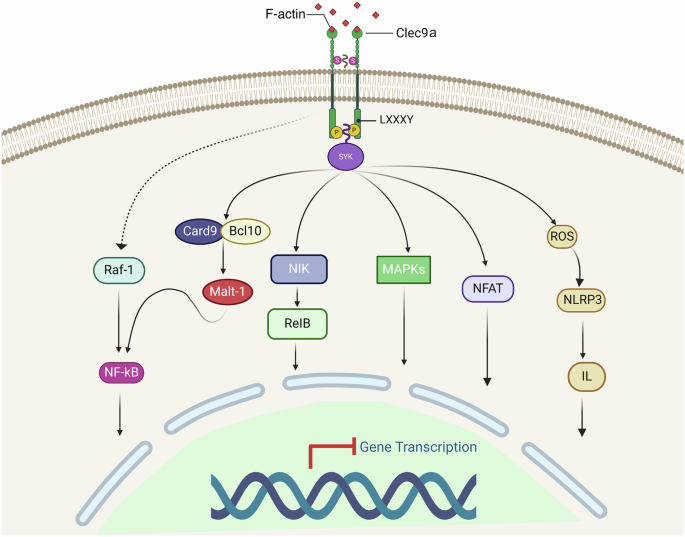

The cytoplasmic tail of Clec9a contains a hemi-ITAM (hemITAM), which is characterized by an essential tyrosine residue at position 7. This motif differs from the typical ITAM sequence, which features an N-terminal tyrosine in a YxxxL sequence for humans and YxxxI for mice, unlike the conventional YxxL sequence. Activation of Clec9a, which is triggered by necrotic cells, is mediated by Syk kinase in a Tyr7-dependent manner74,110,111,112 (Fig. 4). In terms of activation and signal propagation, Dectin-1 and other hemITAM family members, including Clec-2, Clec9a, and SIGN-R3, share similar activation pathways. Upon binding to their respective ligands, these receptors recruit Syk through a phosphotyrosine within the hemITAM motif. This recruitment leads to various downstream effects, such as reactive oxygen species (ROS) production and activation of the NALP3 inflammasome, which in turn triggers pro-IL-1β production113. In addition, for Dectin-1, additional signaling includes the recruitment of Card9, which further regulates the canonical Bcl10-Malt1-mediated NF-κB pathway in DCs. Syk also leads to the activation of the noncanonical NF-κB subunit RelB, independent of Card9 and Bcl10, via NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK)114,115. Further interactions involve the serine-threonine kinase Raf-1, which integrates with the Syk pathway at the point of NF-κB activation when stimulated by agents such as β-glucan curdlan or Candida albicans113,116.

Upon binding to its ligand, Clec9a triggers the Syk-ITAM signaling pathway, which in turn potentially engages multiple downstream pathways, including the Raf-1, CARD9, NIK, MAPK, NF-κB, NFAT, and ROS-NLRP3-Caspase 1 pathways. Created with BioRender.com (Agreement number: YK26UDW783).

In the case of Clec9a, receptor activation through F-actin leads to tyrosine phosphorylation and subsequent activation of Syk family kinases. Syk typically requires the phosphorylation of both ITAM tyrosines for binding via its dual SH2 domains. Effective signaling can also involve the bridging of two monophosphorylated Clec9a molecules53,96,117. The activation of Syk through Clec9a induces important immune functions, including phagocytosis, oxidative burst, cytokine production, cytotoxicity, and, notably, the cross-presentation of dead cell-associated antigens54,117,118. The precise pathways initiating gene transcription for cross-presentation post-Syk activation remain to be elucidated. Known downstream pathways include the activation of Raf, CARD9, NIK, MAPKs, NF-κB, NFAT, and the ROS-NLRP3-Caspase 1 pathway (Fig. 4)113. In addition to its primary functions, Clec9a also modulates macrophage-mediated neutrophil recruitment via the Syk-MAPK signaling pathway and controls tissue damage, innate immunity, and immunopathology119. During Candida infection, Clec9a engagement activates SHP-1, inhibits MIP-2 production by cDC1s, which restrains neutrophil recruitment and promotes disease tolerance120,121,122. Current research has shown that Clec9a triggers signal activation through Syk kinase and promotes the cross-presentation of dead cell-associated antigens via the Syk phosphorylation pathway53,118. However, the mechanism of Clec9a-mediated endocytosis involving Syk phosphorylation needs further investigation. It remains unclear which signaling pathway initiates cross-presentation gene transcription after Syk activation.

Antigen targeting of Clec9a enhances antibody responses

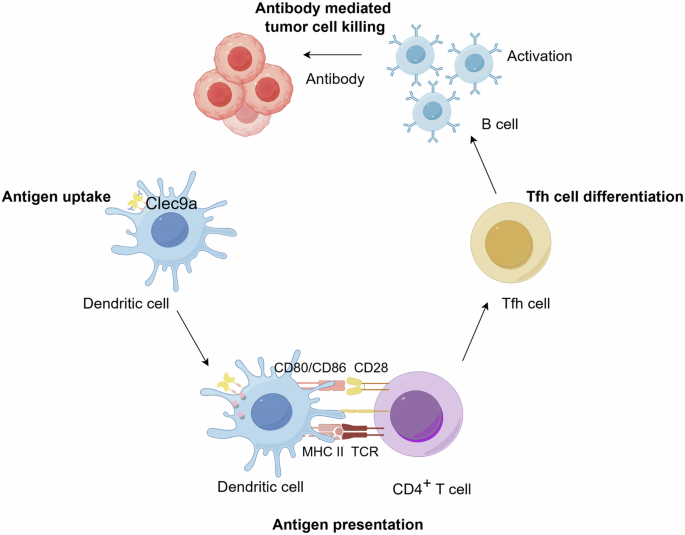

Antigen targeting to DCs is a strategic approach in immunotherapy where antigens are deliberately directed towards specific receptors on DCs to potentiate the immune response112. Antigen targeting to Clec9a, particularly for enhancing the vaccine efficacy, is well-supported by foundational studies in this field34,39,123,124,125. It has been demonstrated that directing antigens to Clec9a facilitates enhanced antibody responses and robust activation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, leveraging the receptor’s inherent immunostimulatory potential42,109,126. Antigen targeting to Clec9a enhances MHC class II presentation and induces CD4+ T-cell responses leading to follicular helper T (Tfh) cells, which are crucial for the development of long-lived, affinity-matured antibody responses and robust humoral immunity (Fig. 5). Notably, the seminal contributions of these researchers have shown that targeting antigens to Clec9a on DCs not only initiates robust antibody and T-cell responses but also specifically enhances the development of memory T cells55,127.

This shows how antigens coupled to anti-Clec9a antibodies are taken up by Clec9a+ cDC1s, leading to antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells via MHC class II. This interaction promotes the differentiation of Tfh cells, which are crucial for the activation of B cells. Subsequently, activated B cells produce antibodies, culminating in antibody-mediated tumor cell death. Created with Figdraw.com.

Targeting antigens to Clec9a+ cDC1s has been found to significantly enhance antibody responses, improving both antibody affinity and titers. This finding expands upon the traditional understanding that cDC2s are primarily responsible for initiating B-cell and Tfh responses128. However, recent findings by Kato et al. suggest that targeting antigens to cDC1 cells through Clec9a can lead to extensive interactions with B cells at the borders of B-cell follicles, providing antigens for B-cell activation. This targeted approach is crucial for inducing B-cell activation and a robust humoral immune response129. Furthermore, research by Yao et al. has shed light on the relationship between Clec9a+ cDC1s and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS). Their data indicate that the expression of Clec9a and its function in cross-presenting dead cell-associated antigens by Clec9a+ cDC1s may be compromised in HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) infections, highlighting a critical area for further investigation in the context of these diseases130. Recent studies have further highlighted the role of Clec9a in enhancing vaccine antibody responses. For instance, targeting weakly immunogenic antigens to Clec9a on DCs has been shown to induce not only cytotoxic T cells but also high levels of antibodies. This approach has been successful even without the use of DC-activating adjuvants. This research underscores the potential of Clec9a for vaccine development, particularly for enhancing humoral immune responses against various antigens131. Moreover, the development of human Clec9a antibodies has facilitated their application as vaccines in cancer immunotherapy. These antibodies specifically deliver antigens to cDC1s, inducing humoral, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell responses, thus representing a promising strategy for developing vaccines against both infectious diseases and cancer109. Recent studies have highlighted the role of Clec9a-targeted DCs in inducing potent immune responses against pathogens and tumors and in potentially compromised HIV/SIV infections, emphasizing their potential in vaccine development and cancer immunotherapy. This approach, particularly through enhancing interactions with B cells and enabling efficient cross-presentation, offers promising avenues for therapeutic interventions and vaccine enhancement. In brief, antigen targeting to Clec9a effectively enhances both humoral and CTL responses while also promotes the development of long-lived memory T cells and Tfh cells, which are key for sustained immunity. Fig. 5 illustrates the role of Clec9a-mediated interactions between DCs, B and T cells in promoting antibody responses.

Antigen targeting to Clec9a promotes antitumor immunity

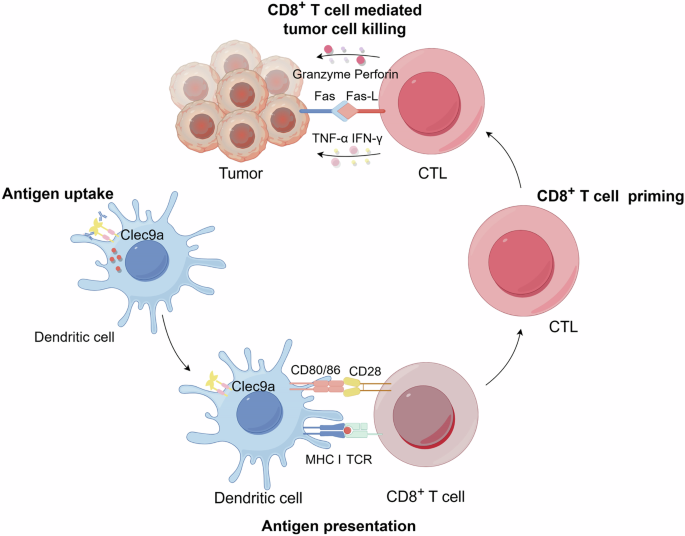

Antigen targeting to Clec9a reduces off-target effects and improves the uptake efficiency by DCs, thereby enhancing antigen presentation and subsequent T cell activation109. Recent studies also show that antigen targeting to Clec9a can enhance both CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses, providing a broad spectrum of immune activation109. Specifically, the MHC class I pathway activates CD8+ T cells, while the MHC class II pathway leads to the activation of CD4+ T cells52,132. Following activation, CTLs engage and destroy tumor cells through mechanisms such as direct killing (via Granzyme, Perforin, and Fas/Fas-L pathway) and indirect pathways involving tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IFN-γ, enhancing antitumor immunity (Fig. 6). Additionally, Clec9a-targeted antigen delivery has been shown to be highly effective in inducing protective immunity against various pathogens and tumors111. Moreover, studies have also demonstrated that DCs lacking CBL E3 ligases have a greater ability to cross-prime CD8+ T cells with antigens from dead cells. These findings suggest that these ligases may enhance the efficacy of both DC-based immunotherapies and tumor vaccines133,134.

It illustrates the process by which antigens targeted to Clec9a on DCs are internalized and presented on MHC class I to CD8+ T cells, leading to their priming and differentiation into CTLs. Following activation, CTLs engage and destroy tumor cells via CTL-mediated direct killing (Granzyme, Perforin and Fas/Fas-L) and indirect killing (TNF-α and IFN-γ). Created with Figdraw.com.

DEC-205 targeting is considered the gold standard in DC-based immunotherapy46, widely utilized for its ability to enhance antigen presentation on both MHC class I and class II135,136. This dual capability enables DEC-205 to activate a broad spectrum of T-cell responses, including both CD4+ helper and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, essential for comprehensive immune responses and sustained antitumor immunity. In comparison, Clec9a targeting is more specialized, focusing primarily on the cytotoxic branch of the immune response137, thus proving highly effective. This approach is particularly advantageous for immunotherapies requiring rapid and potent CTL responses without the extensive immune modulation associated with DEC-205138. While DEC-205 remains a pivotal element in immunotherapy, Clec9a offers a specialized alternative that enhances CTL responses and supports overall immune activation, making it a valuable complementary strategy to DEC-205 in cancer immunotherapy109. Moreover, the role of Clec9a in enhancing cross-presentation by DCs has been explored, suggesting that it routes antigens to early and recycling endosomes to improve CD8+ T cell responses (Fig. 6). This indicates a broader regulatory role for Clec9a in mediating immune responses, further supporting its potential as a target for therapeutic interventions in immune modulation111,112.

Tumor vaccines aim to elicit tumor-specific T lymphocytes, a key tactic in cancer immunotherapy. When antigens, either endogenous or exogenous, are targeted to Clec9a along with an adjuvant, they can inhibit tumor metastasis and bolster antitumor immune responses49,56. Additionally, tumor vaccines typically require multiple doses—often two to three administrations—to achieve a durable and potent antitumor immune response. Clec9a antibodies have strong immunogenicity and may produce anti-idiotype antibodies and reduce the efficacy of tumor vaccines119,139,140,141,142,143. However, conjugating or fusing antibodies with antigens for delivery presents technical challenges. To address this issue, studies have proposed using small peptides, such as the WH peptide, as more convenient antigen delivery carriers. Identified through phage display and synthesized by Fmoc solid-phase synthesis, the WH peptide specifically targets the Clec9a-CTLD region on cDC1s. It enhances the DC’s capacity for antigen cross-presentation, boosts CTL activation, and demonstrates promising antitumor activity in vivo25,144. When coupled with the OVA257-264 epitope, these peptides significantly enhance antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell activation, increase cytokine secretion, and reduce lung pseudo-metastasis loci in a B16-OVA lung metastasis model25. Adjuvants may robustly activate a broad array of innate immune cells, potentially leading to strong inflammatory responses and related side effects145. To develop ideal adjuvant-free DC vaccine carriers, a 12-mer peptide carrier (CBP-12) with high affinity for Clec9a expressed on DCs was developed using an in silico rational optimization method. CBP-12 is an adjuvant-free vaccine carrier that enhances the uptake and cross-presentation of antigens, thus inducing strong CD8+ T-cell responses and antitumor effects in both anti-PD-1-responsive and anti-PD-1-resistant models, even under adjuvant-free conditions108. CBP-12 is a small, convenient, and effective antigen delivery carrier that can be used for the identification of a large number of antigen epitopes and neoantigens.

Further research has led to the development of a functionalized nanoemulsion encapsulating tumor antigens targeting Clec9a (Clec9a-TNE). This nanoemulsion, even without adjuvants, effectively targets and activates cross-presenting DCs, promoting antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation, CTL responses, and effective tumor-specific immunity112. Clec9a-TNE is an ideal antigen delivery system112 that can treat the specific tumor when it encapsulates various tumor-associated antigens146. In addition, type I IFN-targeting Clec9a+ cDC1s displayed strong antitumor activity against human lymphoma in humanized mice without any detectable toxic side effects. Moreover, combined with immune checkpoint blockade, chemotherapy, or TNF, complete tumor regression and long-lasting tumor immunity are observed146. Clec9a/OVA/αGC nanoemulsion codelivery of CD8+ T-cell epitopes with αGC induces alternative helper signals from activated iNKT cells, elicits innate (iNKT, NK) immunity, and enhances CD8+ T-cell antitumor responses to suppress solid tumor growth147. Together, NKT agonists and tumor antigens targeting Clec9a+ cDC1s disrupt tolerance to self-antigens and promote antitumor responses148. An engineered peptide-expressed biomimetic cancer cell membrane (EPBM)-coated nanovaccine drug delivery system (PLGA/STING@EPBM) was developed to deliver stimulator of interferon genes agonists and tumor antigens to Clec9a+ cDC1s. The PLGA/STING@EPBM nanovaccine significantly enhanced IFN-stimulated gene expression and antigen cross-presentation in Clec9a+ cDC1s, thus enhancing the therapeutic effect of STING agonists at low doses on tumors149. These findings indicate that delivery of antigens and drugs targeting Clec9a is highly efficient and safe for immunotherapy.

XCL1 and Flt3L expansion of CD103+ cDC1s150 and subsequent intratumoral injection of SFV-XCL1-sFlt3L enhances antigen cross-presentation and delays tumor progression151. Moreover, Sánchez-Paulete et al. revealed that the antitumor efficacy of anti-PD-1 and anti-CD137 immunostimulatory antibodies relies on Batf3-dependent DCs80. The ability of DCs to cross-present tumor antigens is impaired, which leads to the inability of immunomodulatory antibodies to function therapeutically80. The restricted expression of Clec9a on CD8+ and CD103+ cDC1s, which are critical for cross-presentation, underscores its potential for enhancing the efficacy of immunostimulatory antibodies152. There is evidence that Clec9a is necessary for cross-presentation of dead cell-associated antigens53. We propose that cross-presentation of tumor antigens by Clec9a+ cDC1s may also be a crucial factor that can be exploited to enhance the antitumor efficacy of immunostimulatory antibodies.

The ideal tumor immunotherapy strategy involves the induction of effective immune memory, providing long-term protection to prevent tumor relapse, metastasis, and recurrence. Tissue-resident memory T (Trm) cells play a crucial role in protective immunity, and high levels of tumor-infiltrating CD8+ Trm cells correlate with improved survival153. In virus-infected mice, Clec9a+ cDC1s mediate the cross-presentation of antigen-induced Trm cells and protective immune responses154. Moreover, Clec9a+ cDC1s promoted the retention of CD8+ T cells in the lymph nodes. It is possible that tumor vaccines targeting Clec9a+ cDC1s enhance the cross-presentation of antigens and induce Trm cells and long-term immune memory in tumors. While Clec9a+ cDC1s are not essential for CD8+ T-cell antitumor responses induced by Poly I: C155, the use of adjuvants to prolong antigen exposure and induce DC maturation is significant. Clec9a targeting alone does not induce full DC maturation, evidenced by minimal changes in major maturation markers (CD80, CD86). However, this does not hinder its ability to promote robust antigen cross-presentation, especially via MHC class I, crucial for CD8+ T-cell activation. Clec9a-targeted antigen delivery systems like Clec9a-TNE enhance antigen delivery and cross-presentation and activate DCs sufficiently to improve antigen-specific immune responses, yet without inducing the widespread pro-inflammatory environment typically associated with full DC maturation112. While Clec9a targeting does not directly induce the classical maturation markers or the expression of costimulatory molecules in DCs52,156. Studies have shown that Clec9a+XCR1+ cDC1s are inherently efficient at cross-presenting exogenous antigens, inducing CTL responses without additional maturation signals. This capability is due to their unique intracellular processing pathways that favor antigen presentation on MHC class I molecules, essential for CD8+ T-cell activation72. Moreover, tailored nanoemulsions targeting Clec9a have been demonstrated to activate cross-presenting DCs effectively, promoting antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell proliferation and robust CTL responses, even in the absence of traditional adjuvants112.Taken together, these reports may explain how antigen-targeting Clec9a can induce antitumor effects even without adjuvants.

Furthermore, the adoptive transfer of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-modified T cells has shown remarkable efficacy in treating hematological cancers. However, applying this treatment to solid tumors has been challenging. Research indicates that OVA-Clec9a-TNE—a nanoemulsion that targets DCs via the Clec9a receptor and is loaded with the ovalbumin (OVA) antigen—enhances CAR-T-induced T-cell proliferation and inflammatory cytokine secretion in vitro. When combined with CAR-T cells, this treatment enhances T-cell proliferation and tumor infiltration, ultimately leading to tumor regression147,157. Notably, the combination of OVA-Clec9a-TNE and CAR-T cell therapy effectively induces tumor regression and prolongs survival. These results suggest that delivering antigens to Clec9a+ cDC1s may be a promising tactic for enhancing CAR-T cell efficacy in solid cancers157.

In cancer research, the mevalonate (MVA) metabolic pathway has emerged as a critical target due to its role in supporting tumor progression and immune evasion158. In human cancers, cells often exhibit high MVA metabolic activity, and targeting this pathway has been shown to activate antitumor immunity159. Similarly, in mouse models, research by Xu et al. revealed that blocking the MVA pathway disrupts the prenylation of the small GTPase Rac1, leading to the exposure of F-actin in tumor cells. This exposure is recognized by Clec9a, prompting cDC1s to promote tumor antigen cross-presentation and an antitumor immune response160. Moreover, Masterman et al.161 reported that targeting New York esophageal squamous cell carcinoma 1 (NY-ESO-1) to human Clec9a enhances the cross-presentation of antigens by CD141+ cDC1s, leading to increased activation of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells. This method demonstrated superior efficacy in reactivating NY-ESO-1-specific T-cell responses in vitro using cells from melanoma patients and in humanized mice, compared to targeting DEC-205-NY-ESO-1161. Similarly, Pearson et al. showed that delivering Wilms’ tumor 1 antigens to CD141+ cDC1s via Clec9a stimulates stronger antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses than targeting with DEC-205. This finding further emphasizes the potential effectiveness of Clec9a targeting in cancer immunotherapy162.

In addition, Koster et al.163 demonstrated that injecting CpG-B at primary tumor excision sites recruits Clec9a+ and CD14+ cDC1s, leading to immune activation, increased melanoma-specific CD8+ T-cell rates in peripheral blood, and prolonged recurrence-free survival. Recent advancements also include the use of ferritin nanoparticles for targeting Clec9a in vaccine development. This approach, involving anti-Clec9a antibodies, enhances serum antibody titers and germinal center formation, although its effectiveness varies with different antigens. Such findings open up new avenues for the precise delivery of tumor vaccines164. Meanwhile, Huang et al.165 designed a nanovaccine that co-delivers tumor antigens and iNKT cell agonists to CD141+ cDC1s by targeting Clec9a. This innovative approach activates CD141+ cDC1s and iNKT cells, eliciting potent antigen-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. This highlights the potential of Clec9a in nanovaccine development. On the other hand, Cueto et al.166 revealed a mechanism by which Clec9a impairs the therapeutic effects of Flt3L on tumors. Specifically, Clec9a reduces specific inflammatory gene expression in cDC1s, leading to decreased levels of tumor-infiltrating cDC1s. This finding suggests that blocking Clec9a may enhance the antitumor effect of strategies involving high Flt3L expression166.

Additionally, recent innovations include the application of a bispecific Clec9a-PD-L1-targeted type I IFN (AcTaferon, AFN) and the development of a bispecific DC-T cell adapter (PD-1/CLEC9A), which enhance these immunotherapeutic approaches in mouse models167. This strategy is related to the expression of Clec9a in mouse pDCs, but not in human pDCs. While AFN enhances the immunogenicity in the tumor microenvironment without delivering antigens, BiCE promotes the physical interaction between cDC1s and CD8+PD-1+ T cells, showing pro-inflammatory response activation. Both approaches underscore the potential of using type I IFN in combination with other targeting strategies like Clec9a to create a multifaceted approach to cancer immunotherapy preclinical settings167,168. These studies underscore the potential of combining Clec9a targeting with type I IFN, which is a promising strategy for various cancer types168. Although promising in mouse models, further studies are required to evaluate the applicability and effectiveness of these strategies in human systems. Although promising in mouse models, further studies are required to evaluate the applicability and effectiveness of these strategies in human systems. Table 3 provides a detailed comparative overview of outcomes from both mouse models and human studies, highlighting key advancements and the translational potential of Clec9a-targeted therapies.

Conclusion

DC-based tumor vaccines are progressing rapidly, showing substantial promise in both animal studies and early clinical trials. Importantly, the success of checkpoint blockade inhibitors has reinvigorated the potential of DC-based strategies in cancer immunotherapy, especially in combination therapies. This synergistic approach is particularly promising for advanced cancers, such as melanoma, where the combined use of DC vaccines and radiotherapy may offer enhanced benefits for patient outcomes. Central to these advances is the targeting of the cDC1 subset, which has emerged as a powerful method for delivering antigens specifically to cDC1s and transporting other therapeutic agents, such as adjuvants and STING agonists, to amplify immune responses in a targeted manner. Clec9a is exclusively expressed on human cDC1s and plays a fundamental role in antigen cross-presentation, which is crucial for activating effective immune responses and improving overall cancer immunotherapy outcomes. This review has detailed the structural characteristics, expression profiles, signal recognition mechanisms, and immune modulation functions of the Clec9a+ cDC1s subset, highlighting its capacity for antigen cross-presentation and CD8+ T cell priming, both of which play a significant role in driving antitumor immunity. Additionally, the signaling pathways activated by Clec9a, particularly through the ITAM-Syk pathway, represent a critical area for ongoing research, as a deeper understanding of these pathways may be essential for fully realizing the therapeutic potential of DC-based vaccines in cancer treatment. Antigen targeting Clec9a, which facilitates precise antigen delivery to cDC1s and induces robust humoral, CD4+, and CD8+ T-cell responses, positions these antibodies as promising candidates for next-generation vaccines against both infectious diseases and cancer. Recent advances in DC biology have also underscored the pivotal role of cDC1s, especially those characterized by Clec9a expression, in mediating tumor immune responses, thereby establishing this DC subset as an attractive target in vaccine development. As research into Clec9a continues to expand, our understanding of its applications in cancer immunotherapy deepens, further establishing this receptor as a key target for innovative DC-based therapies and advancing the frontier of cancer treatment.

Responses