Exploring the spatial distribution characteristics and formation mechanisms of Hakka folk settlements: a case study of Hakka traditional architecture in southeastern China

Introduction

The emphasis on traditional culture in China has gradually increased in recent years. The General Office of the State Council put forward Opinions on Further Strengthening the Protection of Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2021. It stressed that efforts should be made to protect and promote China’s intangible cultural heritage with excellent traditional culture. Hakka culture is one of them, demonstrating the richness of Hakka people’s creations to improve their living conditions and embodying unique cultural styles (Hsien et al., 2022; Hua et al., 2018; Leung, 2015). The Hakka is a distinct Han ethnic group in southern China, formed as a result of the many southward migrations of the Han throughout history (Zheng et al., 2013). Settlement is the basic unit of human activity and the place where people interact with the natural environment (Liu et al., 2021). In the process of exploring the causes of the formation of Hakka settlements, the development of Hakka culture can be better understood and portrayed, thus helping to realize the effective preservation and inheritance of Hakka culture. This will not only contribute to the promotion of China’s intangible cultural heritage with its excellent traditional culture but also strengthen the knowledge of the rich creations of the Hakka people to improve their living conditions and further highlight the unique charm of the Hakka culture. Therefore, studying the formation of Hakka settlements and understanding the development of Hakka culture is crucial for the preservation and transmission of Hakka culture.

As the most direct and visible landscape to which human activity is attached (Hansen, 1984), the settlement has attracted much attention from archeology, geography, and anthropology scholars. Lu et al. (2018) analyzed archeological results from the Songshan region of China through the Self-Organizing Feature Maps (SOFM) technique, which revealed that the scale and distribution patterns of prehistoric settlements were closely linked to environmental and cultural factors. Taylor’s (1942) method of genetic analysis explored the patterns of settlement spatial layout and provided a new perspective for understanding settlement development. The critical role of economic activities and security needs in settlement selection and development is emphasized by the categorical study of Zhou et al. (2013) as well as the observations of Cazzella and Recchia (2018), who noted that the development of settlements is dependent on economic centers and is significantly influenced by agricultural and military factors. The important contribution of community participation and multicultural exchanges to the sustainability of agglomerations is confirmed by the research of Wei (2017) and the findings of Hassan et al. (2020), who explored the impact of collaboration between communities, NGOs and authorities on economic sustainability. The specific impacts of environmental factors on settlements have garnered significant attention. Shen et al. (2023) pointed out the differing environmental influences on the development of urban agglomerations in China and the United States, while Liu et al. (2023) focused on rural settlements in the hilly regions of Sichuan, proposing optimization strategies and risk management measures, emphasizing the importance of environmental adaptation and protection. Scientific assessment and decision support play a pivotal role in settlement development. The changes in population dynamics have a decisive impact on the geographical distribution of settlements. Furthermore, changes in demographic dynamics are also one of the decisive factors affecting the geographical distribution of settlements. The study by José Balsa-Barreiro et al. (2021) utilized spatial network analysis to examine changes in demographic dynamics at the local scale, providing methodological insights into internal population movements and redistribution within settlements. Chen et al. (2023) utilized multi-criteria decision-making and spatial visualization techniques to provide a scientific basis for assessing the suitability of traditional villages in Hunan, showcasing the application potential of modern technological tools in settlement conservation and development. While existing studies have explored the complexity of settlement development from multiple disciplinary perspectives, a systematic analysis of the role of architectural distribution and morphology in settlement evolution is still missing.

Architecture is a human landscape created on the earth’s surface by using building materials and following specific architectural and cultural patterns. It is inevitably restricted and influenced by the elements of the geographical environment (economic base, superstructure, natural environment, etc.) (Wang et al., 2022). As Karakul (2015) pointed out, residential buildings are carriers of history and culture, passing on the material and intangible culture of traditional architecture. Mahoney (2018) found through his study of traditional buildings in the plains of Damar that these buildings were mainly of a defensive nature, while Öztank’s (2010) study of traditional wooden houses in Turkey revealed that transportation and the high efficiency of wood use under the constraints of building materials. These studies show that traditional architectural forms not only imply past lifestyles but also reflect a deep understanding of and adaptation to the environment. In particular, the Hakka Tulou is striking, not only as a product of Hakka culture, but also as a visual embodiment of Hakka folklore, migration history, and social organization (Hua et al., 2018). The unique architectural styles and structures of Hakka Tulou reflect the Hakka people’s deep understanding of their living environment and their need for social stability and group defense (Yelland, 2013). Wang et al. (2012) analysis of the formation and development of Hakka Tulou villages further underscores the uniqueness of Hakka Tulou architecture in terms of its physical form and socio-cultural context. Li et al. (2023) took advantage of the fact that Hakka buildings have unique styles and architectural features, proposing a new interpretable dimensionality reduction (XDR) framework to study the ethnic styles of rural dwellings in Guangdong, China, from the perspective of artificial intelligence. These research results provide perspectives for an in-depth exploration of the interaction between architecture and culture and provide important references for understanding the role of architecture in cultural inheritance and social development.

In summary, current research on the genesis of folk settlements mainly uses qualitative methods such as field studies and literature studies. The results are highly subjective and lack the support of actual data. Existing studies on the causes of the formation of Hakka folk settlements, on the other hand, have focused on the history of Hakka development and folk culture. After several migrations, Hakka ancestors settled in the border areas of Jiangxi, Fujian and Guangdong in China. Ma et al. (2023) utilized a variety of statistical and spatial analysis methods to provide a clear analysis of the spatial distribution characteristics, patterns, density, and trends of traditional villages in Fujian Province. This provides a foundation for studying the many Hakka traditional buildings that have been preserved in the area and offers excellent opportunities for research purposes. This paper combines the approach of qualitative and quantitative analysis, aims to provide new perspectives and nuanced understandings on the causes of Hakka settlements formation, and makes contributions in the following three aspects. This study (1) uses geographic concentration index, imbalance index, nearest neighbor index, and kernel density analysis to gain insight into the spatial distribution characteristics of Hakka traditional architecture, (2) undertakes a comprehensive analysis of how natural geography and cultural factors have shaped the formation of Hakka folk settlements, (3) provides an in-depth discussion of the geographical and social factors that led to the formation of Hakka folk settlements, as well as suggestions for their preservation and management.

Materials and methods

Study area

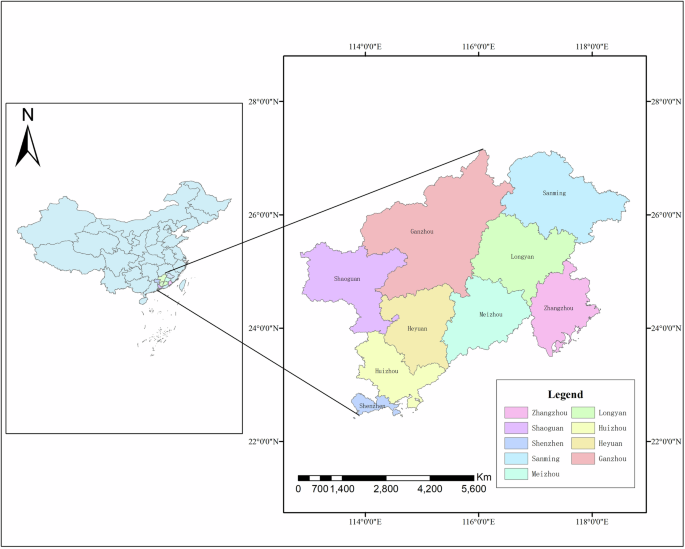

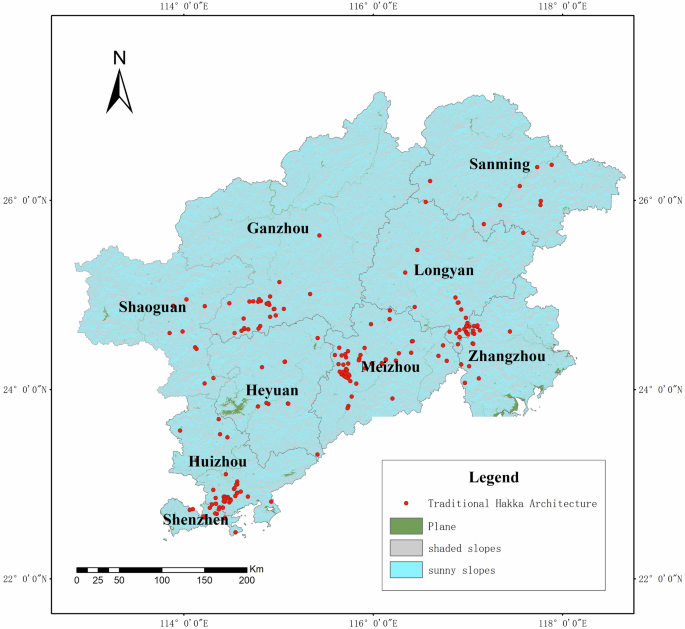

The Hakka people primarily inhabit regions in the southeastern part of China, including Ganzhou, Longyan, Meizhou, Heyuan, Shaoguan, Huizhou, Shenzhen, Sanming, and Zhangzhou (Fig. 1). These areas share similar customs, ideological values, and the distinct Hakka dialect, reflecting a profound historical and cultural heritage. The Hakka people, renowned for their resilience and bravery, have successfully preserved their unique language, customs, dietary traditions, and architectural styles, fostering a distinct culture that emphasizes family and community unity (Chen, 2023). Characterized by mountainous and hilly terrain with intersecting valleys and rivers, this unique natural environment provided a refuge for the Han people displaced by war in the Central Plains.

Map of Hakka region.

Data

The names of Hakka traditional buildings were collected from the Baidu Encyclopedia and Fujian Hakka famous buildings (Luo et al., 2011). After that, the coordinates (latitude, longitude) of each building were extracted from the Baidu map. In total, data from 216 Hakka traditional buildings were obtained. The digital terrain model (DTM) data were collected from the Geospatial Data Cloud (http://www.gscloud.cn) with a spatial resolution of 30 m. The slope, slope direction, and elevation data used in the analysis were obtained by extracting a digital elevation model with the terrain analysis tool of the geographic information system (GIS) software. The relevant written records, shapes and socio-economic information regarding Hakka traditional buildings were gathered from Baidu Encyclopedia entries and “Famous Hakka Residences in Fujian”. Additionally, the books addressing population migration and quantitative changes in the Hakka region referenced in this study were sourced from “Jianxiong Ge: Chinese Immigrants History (Volume 1)”.

Methodology

Geographic concentration index, imbalance index, nearest neighbor index, and kernel density analysis were used to gain insight into the spatial distribution characteristics of Hakka traditional architecture and to reveal its historical background and cultural connotations.

Spatial distribution patterns

The nearest neighbor index method measures the spatial distribution of point features by using the distribution status of random patterns as a criterion (Guo et al., 2020). The nearest neighbor index calculates the average distance between each element’s center of mass and the center of mass of its closest neighbor to determine the distribution pattern (Lee et al., 2020). This helps to understand the spatial characteristics of the architectural layout within the settlement and provides clues for exploring the causes of settlement formation.

Where (bar{{r}_{o}}) is the average distance between each architecture point and its closest point,(n) is the numbers of actual buildings, ({d}_{i}) is the distance from building (i) to its closest neighboring point; (bar{{r}_{E}}) is the average distance under a random distribution;(A) is the area of the study area. The spatial distribution pattern is considered clustered when the mean nearest neighbor ratio R is less than 1. Conversely, when R exceeds 1, the pattern tends to be more dispersed or diffused.

Spatial distribution characteristics

The application of the Geographic Concentration Index (GCI) and Imbalance Index in this study serves as robust methods to evaluate spatial uniformity. These indices offer a nuanced understanding of the spatial distribution patterns of Hakka traditional buildings, thereby facilitating a more detailed and holistic analysis.

GCI is an important indicator that describes the degree to which elements of geographic research are centralized within a region (Bao et al., 2002). Compared to other indices, GCI more directly reflects the degree of geographic concentration. It is more effective in analyzing the spatial distribution characteristics of clusters (Guy et al., 2002). This study uses the geographic concentration index to quantify the spatial distribution of Hakka traditional buildings in this study area (Eq. 3).

Where G is the geographic concentration index, n is the total number of cities, ({X}_{i}) is the number of Hakka traditional buildings in the city i, and (T) is the total number of cities in the study area (9 cities). The range of G values is between [0–100], and the larger the G value, the more concentrated the distribution of Hakka traditional buildings is. The smaller the G value is, the more dispersed the distribution of Hakka traditional buildings is. By assuming an even distribution of buildings in the whole study area, an even geographic index (G1) can be obtained. If G > G1, it means the concentrated distribution of Hakka traditional buildings, and if G < G1, it implies that Hakka traditional buildings are dispersed.

The imbalanced index can be used as an indicator to quantify the degree of difference in the weight of the two sets of data (Liu et al., 2021). This helps to understand the spatial characteristics of the architecture among different clusters can be obtained, which will help formulate targeted policies and development plan. In this work, the imbalanced index is used to analyze the degree of uniformity in the distribution of Hakka traditional architecture within different regions of the Hakka population territory (Eq. 4).

Where S is the imbalanced index of Hakka traditional buildings, n is the number of regions, and ({y}_{i}) is the cumulative percentage of Hakka traditional buildings within each municipality ranked from the largest to the smallest in the total study area in the i-th region. If S = 0, it means that the Hakka traditional buildings are evenly distributed in each region; If 0 < S < 1, it means that the buildings are not evenly distributed; If S = 1, it means that the Hakka traditional buildings are concentrated.

To reflect the spatial distribution characteristics of Hakka traditional buildings intuitively, the visualization function of GIS was used for kernel density mapping. Kernel density analysis is a classic unsupervised learning method that calculates the density of point elements per unit area using a mathematical function to create a smooth surface (Yann et al., 2024). The value decreases as the distance from the point increases, reaching zero at the search radius position. Through kernel density analysis, it is possible to explore the spatial relationship between Hakka traditional architecture and other geographic elements and reveal the geographic environment and social factors behind the distribution of architecture. The kernel function density expression is as follows:

Where (kleft(frac{x-{x}_{i}}{h}right)) is the kernel density function, h (h > 0) is the bandwidth value; (({rm{x}}-{{rm{x}}}_{{rm{i}}})) is the distance from the estimation point to the sample x. The closer the estimation point is to the central sample point, the greater the density (Mostafa et al., 2020).

These methods collectively construct a multidimensional spatial analysis framework, which helps to analyze the spatial characteristics of traditional Hakka architecture in depth and to assess the formation of Hakka folk settlements.

Results

Analysis of spatial distribution of Hakka traditional buildings

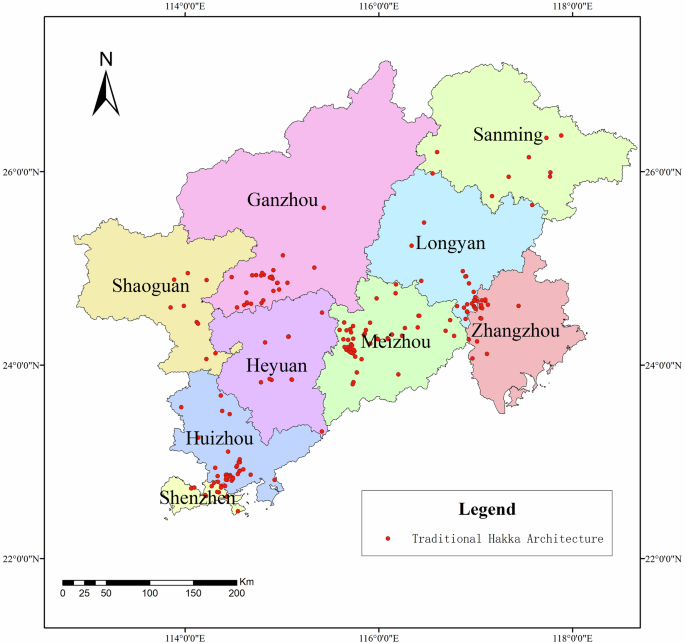

Considering Hakka traditional buildings as point features in space, the distribution of each point in each administrative unit was counted and summarized (Fig. 2). The results show that 81.02% of Hakka buildings are located in five regions, including Meizhou, Huizhou, Longyan, Ganzhou and Shenzhen (Table 1).

Distribution of Hakka traditional building sites.

Spatial distribution patterns of Hakka traditional buildings

There are three main patterns of spatial distribution: random distribution, sparse distribution, and cluster distribution (Chen et al., 2023). According to the nearest neighbor index model, the nearest neighbor index of 216 Hakka traditional buildings was measured with the help of GIS spatial analysis tools. The average actual observed distance ((bar{{r}_{o}})) of Hakka traditional buildings within the overall Hakka region is 6802 m, the expected distance ((bar{{r}_{E}})) is 12,728 m, and the z-score value is −13.09, with p-value < 0.05. Finally, the average nearest neighbor ratio R between the actual observed distance and the theoretical average distance is 0.53 < 1 indicating the cluster spatial distribution of Hakka traditional buildings in the study area.

Spatial distribution characteristics of Hakka traditional buildings

The study area was divided into nine administrative units to calculate the geographic concentration index, namely Ganzhou, Longyan, Meizhou, Heyuan, Shaoguan, Huizhou, Shenzhen, Sanming, and Zhangzhou. Through Eq. (3), the geographic index value was calculated as G = 39.58 and G1 = 24. From the observation that G > G1, it can be inferred that the distribution of Hakka traditional buildings is clustered and uneven. This finding also corroborates the spatial aggregation pattern of Hakka traditional buildings in the Hakka region, as previously indicated by the Nearest Neighbor Index.

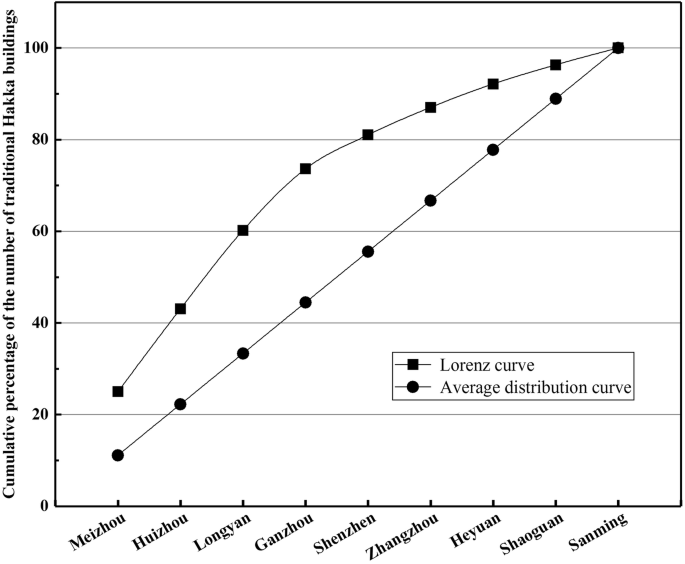

Based on the imbalance index formula, the spatial distribution index S for Hakka traditional architecture is calculated to be 0.3958. Given that S is greater than 0 and less than 1, this suggests that Hakka traditional architecture is not evenly distributed across the Hakka region. The Lorenz curve, derived from the imbalance index (Fig. 3), illustrates that over 80% of Hakka traditional buildings are concentrated in Meizhou, Huizhou, Ganzhou, Longyan, and Shenzhen. This further confirms that Hakka traditional architecture is highly concentrated and unevenly distributed in space.

Lorenz curve of the spatial distribution of Hakka traditional buildings.

According to the results of the study, it is evident that the distribution of Hakka traditional architecture is marked by significant aggregation and unevenness, with a predominant concentration in Meizhou, Huizhou, Ganzhou, Longyan, and Shenzhen.

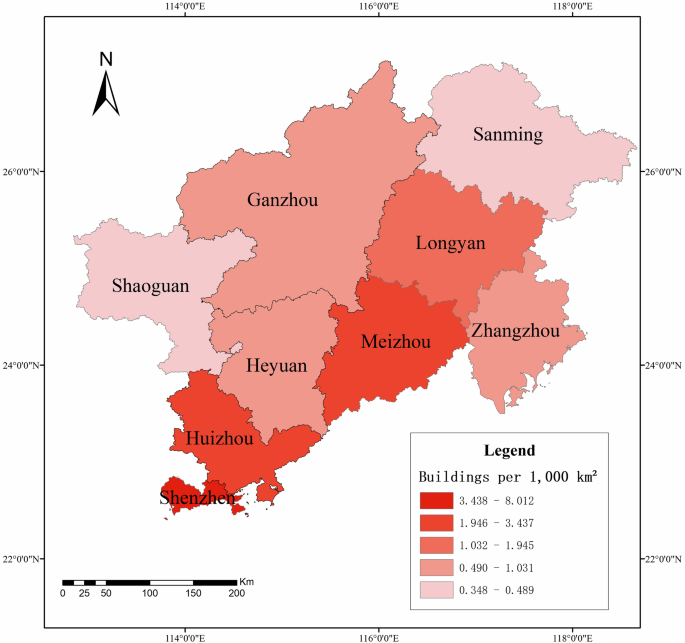

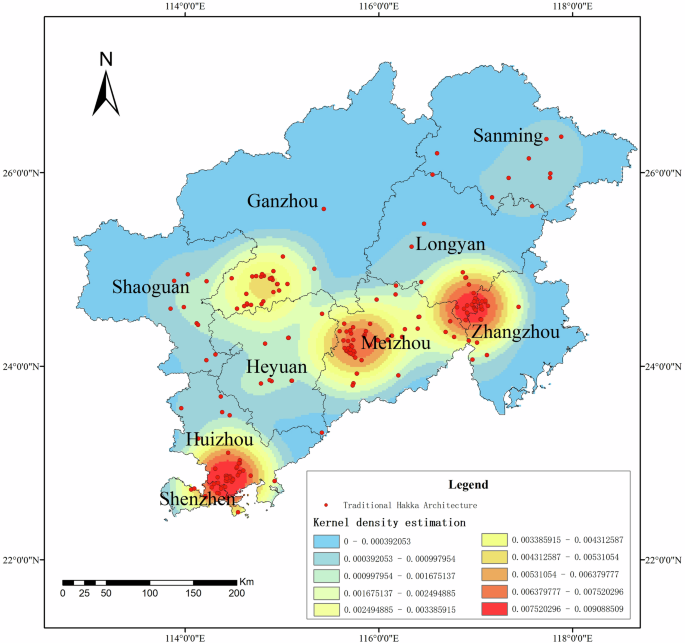

The distribution density of Hakka traditional buildings was calculated based on the number of such buildings and the area of each region (across 9 regions). Table 2 presents the statistical table of the distribution density, while Fig. 4 visualizes this density. The highest density is observed in Shenzhen at 8.012 × 10−³ units/km², whereas the lowest is in Sanming at 0.348 × 10−³ units/km². Kernel density analysis was employed to generate a map (Fig. 5) that illustrates the overall distribution pattern. This pattern is characterized by significant aggregation and minimal dispersion, with five main concentrations located in the southern part of Ganzhou City, the eastern part of Shenzhen City, the southern part of Huizhou City, the eastern side of Meizhou City, and the east-west junction of Longyan City and Zhangzhou County. This analysis further confirms the highly concentrated and uneven spatial distribution of Hakka traditional architecture.

Distribution density map of Hakka traditional buildings.

Kernel density map of Hakka traditional buildings.

Analysis of the influence of geographical factors on Hakka traditional buildings

Analysis of the impact of slope of Hakka traditional buildings

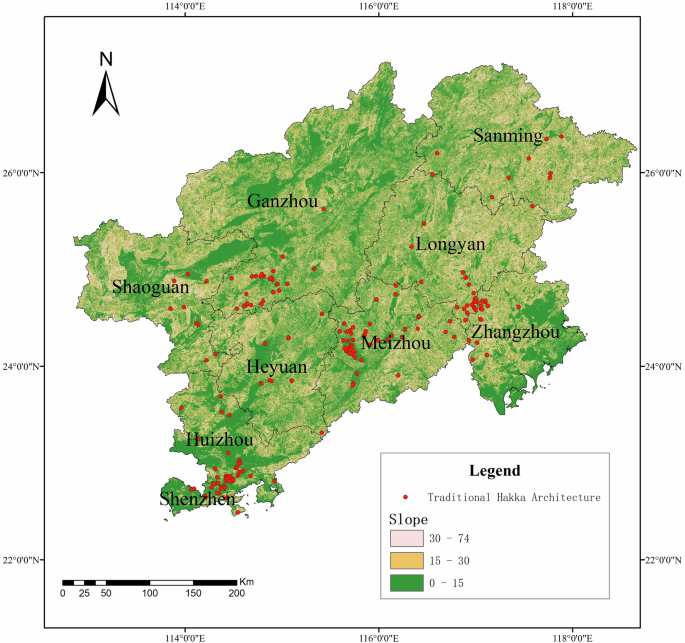

The slope classification adheres to the International Geographical Union Commission on Geomorphological Surveys and Geomorphological Mapping’s detailed topographic map application standards, delineating seven distinct categories: plains (0°–0.5°), slight slopes (0.5°–2°), gentle slopes (2°–5°), slopes (5°–15°), steep slopes (15°–35°), craggy slopes (35°–55°), and vertical cliffs (55°–90°). A detailed classification and count of Hakka traditional buildings across these slope classes are presented in Table 3. The data reveals that the majority of these buildings, totaling 95, are situated on slopes, followed by steep slopes and gentle slopes with 59 and 44 buildings, respectively. Conversely, the least number of buildings are found on plains and craggy slopes, with only one and two buildings respectively. The thematic map of Altitude (Fig. 6) visually underscores the predilection of Hakka traditional buildings for sloped terrains.

Thematic map of slopes distribution of Hakka traditional buildings.

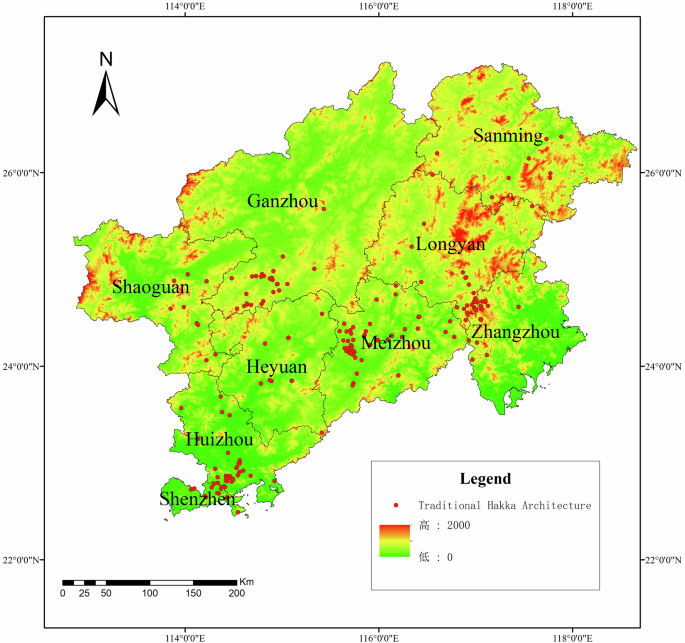

Analysis of the impact of altitude of Hakka traditional buildings

The Hakka region is mainly located in the southeastern part of China and is the main distribution zone of the Southeastern Hills. The elevation of the Southeastern Hills is mostly between 200 and 500 m above sea level, with only a few major peaks exceeding 1500 m above sea level. Despite the complex and varied terrain, low hills prevail, interspersed with mountain basins and valleys. Consequently, Hakka traditional architecture is predominantly situated below 1000 m in elevation, with a significant concentration below 500 m. Specifically, out of a total of 182 buildings, 113 are located in plains, 69 in hilly areas, and 34 in low mountainous terrain between 500 and 1000 m (Table 4). The thematic map visualization (Fig. 7) vividly illustrates that these buildings are largely found in lowland areas, which aligns closely with Hakka agricultural culture. The preference for lowland areas is attributed to their suitability for agricultural production (Chen et al., 2022).

Thematic map of altitude distribution of Hakka traditional buildings.

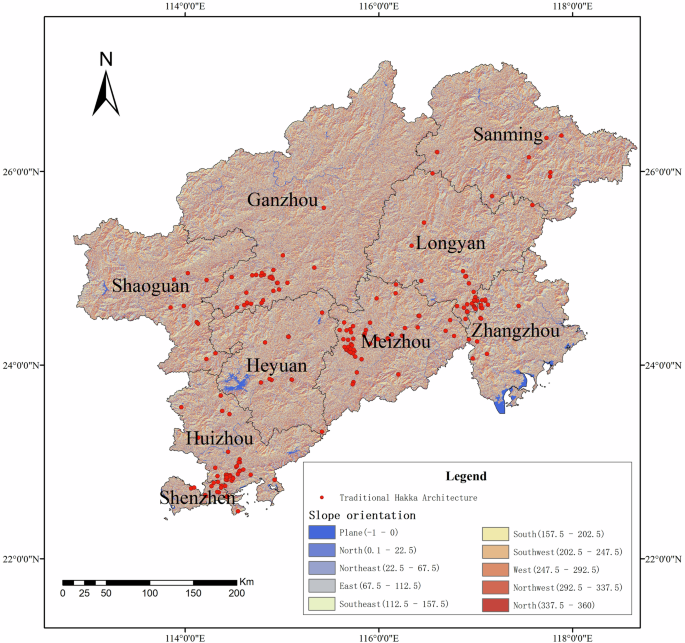

Analysis of the impact of slope direction of Hakka traditional buildings

In analyzing the slope direction of Hakka traditional buildings, the 360° compass is evenly divided into eight sectors, each spanning 45°. Based on this segmentation, the slope directions of Hakka traditional buildings predominantly align with three cardinal orientations: southwest, northeast, and southeast (Table 5). This distribution pattern is visually represented through thematic mapping (Fig. 8). The prevalence of these specific slope directions underscores the strategic construction orientation of Hakka traditional buildings and their harmonious adaptation to the local environment. Southwest-facing slopes offer optimal sunlight exposure, which is conducive to crop cultivation and also facilitates effective ventilation and rainwater drainage during the warmer seasons. Northeast-facing slopes, in contrast, provide a cooler and more humid microclimate, which is beneficial for certain types of crops and human habitation. Southeast-facing slopes strike a balance, combining adequate sunlight and ventilation with a moderate level of humidity, thus catering to both agricultural needs and residential comfort (Yu and Zaijun, 2017).

Thematic map of slope direction distribution of Hakka traditional buildings.

Analysis of the impact of shaded and sunny slopes of Hakka traditional buildings

According to the basic theory of physical geography, slope orientation is divided into shady slopes that cannot be illuminated by the sun and sunny slopes that face the sun. The Hakka traditional buildings are generally located in the northern hemisphere, with south-facing slopes as the sunny slopes and north-facing slopes as the shady slopes. The shaded slopes, therefore, range from 0° to 90° and 270° to 360°, while the sunny slopes range from 90° to 270°. The statistical results show that the number of Hakka traditional buildings on the sunny slope is 105, while the number on the shady slope is 111. Figure 9 is a thematic map of the distribution of sunny and shaded slopes of traditional Hakka architecture.

Thematic map of sunny and shaded slopes distribution of Hakka traditional buildings.

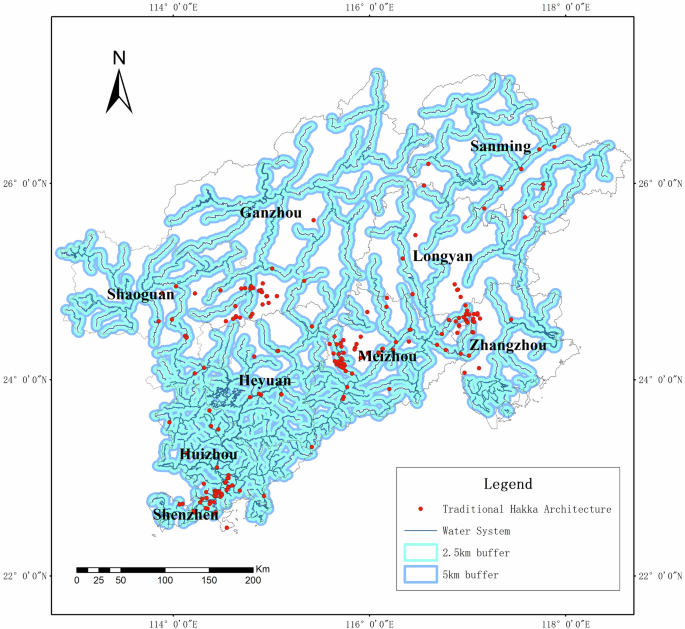

Analysis of the impact of water system of Hakka traditional buildings

The distance from Hakka traditional buildings to water sources was analyzed with the buffer analysis function, where 2.5 km and 5 km were set as the distance parameters for buffer analysis (Fig. 10). The results were: 90 Hakka buildings were located within the buffer zone of 2.5 km, and 137 Hakka traditional buildings were distributed within 5 km of the water system. They account for 63.43% of the total number of Hakka traditional buildings. Further analysis shows that the 2.5-km buffer zone accommodates a greater concentration of Hakka traditional buildings relative to the 5-km buffer zone. This suggests that areas closer to water sources are more favored by Hakka traditional architecture, which may be influenced by factors such as water access and convenience (Cui et al., 2021). This finding has important implications for local community planning and cultural heritage preservation and contributes to a better understanding of the siting characteristics of Hakka traditional architecture and its relationship with the environment.

Schematic diagram of the buffer zone of the water system in the Hakka region.

Analysis of orientation and types of Hakka traditional buildings

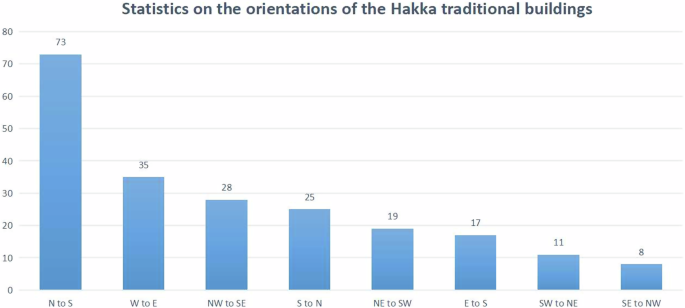

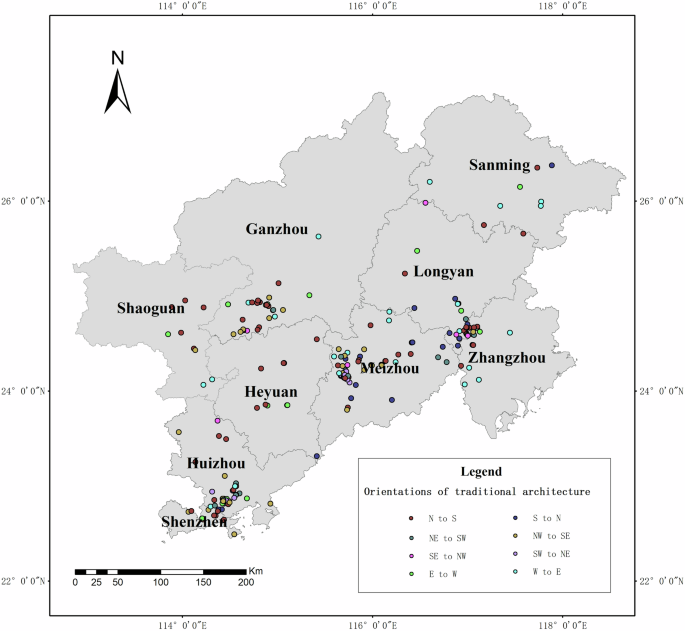

Orientation of Hakka traditional buildings

When examining the orientation of Hakka traditional buildings, it is observed that 56% of these buildings face the south, with 13% oriented towards the southeast and 9% towards the southwest. The remaining 44% are oriented in the other three directions (Fig. 11). To provide a more intuitive understanding of the distribution of Hakka traditional building orientations, thematic maps have been developed (Fig. 12). The dominant orientation of Hakka traditional buildings is north-south, which can be attributed to both climatic and topographical factors in China. Geographically, China’s terrain is higher in the northwest and lower in the southeast. Considering issues related to rainfall and drainage, settlements were primarily constructed facing southward. The high, unobstructed northwest terrain ensures ample sunlight for the buildings and also provides strategic protection for the Hakka people against invasions.

Statistics on the orientation of the Hakka traditional buildings.

Thematic map of orientation of Hakka traditional buildings.

Most regions in China experience a monsoon climate. In winter, the Siberian cold front from the north brings northeast and northwest winds. In summer, warm and humid air currents from the southeast Pacific Ocean and the southwest Indian Ocean prevail. Buildings that face southward align with this climatic pattern. They shield against cold air, maintaining warmth indoors in winter, and capture the southeast or southwest breeze in summer, which passes through the buildings, providing a cooling effect (Xia et al., 2017). Given that the sun rises in the east and sets in the west, buildings facing south in most parts of China enjoy extended periods of sunlight exposure. This abundance of light keeps interiors bright, which is considered favorable in the context of Fengshui, a traditional Chinese geomancy practice (Guan et al., 2024). Overall, the principle of south-oriented settlements reflects the Chinese understanding of natural geography and is a response to the characteristics of the natural environment.

According to ancient Chinese Fengshui, it is best to build a building with a backdrop of a mountain and water (Chang et al., 2009; Guan et al., 2024). A mountain behind the building gives a sense of security and helps the building to keep pleasant energy. The topography of building is low in the front and high in the back. The traditional concept of water in China is wealth. Therefore, the flow of living water gives people an image of vitality, and the water surrounding the building will bring the residents fortune and wealth (Knapp, 2010). In such a Fengshui-based environment, the fortune of the residents is enhanced. Consequently, the family’s quality of life is improved, which also reflects the Chinese vision for a better life. This is why some Hakka buildings face mountains or rivers instead of following the north-south orientation.

Types of Hakka traditional architecture

The structure of Hakka architecture often adapts to the local natural environment, such as terrain, climate, etc. For example, the circular design of building not only adapts to rainy climates but also utilizes limited land resources, which play an important role in the formation and development of settlements.

Hakka architectural types can be categorized into four main groups: square enclosed building, round-dragon building, square earth building and round earth building (Table 6). Table 7 provides a detailed count of the number of buildings in each category. Among these, the most prevalent type is square building, which includes both square enclosed building and square earth building, totaling 143 buildings.

The Mentang building is one of the most representative of the square enclosed houses. It is said that ordinary families could not build the Mentang House, but only the scholarly families who had been ranked in the imperial examinations or by the families of former dignitaries. The Round-Dragon House is a Hakka folk house building with great Hakka characteristics. Vertical walls enclose the three sides of the round-dragon house, the back wall is half-moon shaped, and the half-moon section is known as the “enclosure”, so the whole can be seen as a combination of “half-moon + square”. There is a pond usually dug in front of the Mentang House’s front door, also called “moon pond” because of its half-moon shape. The moon pond provides water for the Hakka people inside the house to live their daily lives and plays a role in fire prevention and extinguishing. The square and round earth buildings are fully enclosed, multi-story buildings with clay as the main building material. Inside the square earth building, ancestral halls, theaters and other halls are built separately, most of which are square. As the external structures of square and round buildings differ, there is no hall structure inside the round earthen buildings. In large square earthen buildings, the hall is always placed in the middle of the axis, with the largest openings and the most ornate decoration, in a very prominent position (Tao et al., 2018; Ueda, 2012).

Some square buildings have blockhouses at the corners, also known as the “four points of gold”. The four corner blockhouses are usually equipped with lookouts and trumpet windows, mainly for observation of the building’s perimeter and the ability to extend guns from the small openings or windows for the building’s self-defense function to repel intruders. The round earth building is shaped like a fortress, and the observation field of the building is wider without dead ends, which is more conducive to detecting enemy situations than the square building in playing a defensive role.

In short, the Hakka traditional buildings are mainly located in areas with an altitude of 500 m and a slope of less than 15°, with more than half of them facing the south direction. The spatial distribution of Hakka traditional buildings is characterized by more aggregation and less dispersion.

Discussion

Geographical factors in the formation of Hakka folk settlements

Influence of geographical environment on Hakka traditional architecture

Hakka traditional architecture has its characteristics in different areas within the Hakka region. However, because of the common cultural, historical, and natural environmental backgrounds between the Hakka regions, the Hakka traditional architecture from different areas is, on the whole, extremely similar in architectural forms and styles. For example, Hakka traditional architecture is centripetal, defensive, and enclosed. The Hakka ancestors experienced long migratory journeys and many harsh and complex environments. And the Hakka people have developed hard-working, sincere, and modest characters, enabling them to adapt and survive in an unfamiliar and complex environment (Wang et al., 2012). This is why, in the face of the mountainous and forested environment of southern Jiangxi and western Fujian, the Hakka were able to build their own houses and live together as a clan to defend themselves against foreign enemies. On the other hand, the building materials of Hakka traditional architecture are mainly made of rammed earth and stone bricks, and the exterior and interior of the buildings are not decorated, which reflects the pure and modest character of the Hakka people.

Influence of geographic factors on the spatial distribution of Hakka traditional architecture

The results show that the distribution of Hakka traditional buildings has the spatial distribution characteristic of “more clustered and less dispersed.” Natural geography is undoubtedly a very important factor influencing the spatial distribution of Hakka traditional architecture, and different regions show different distribution characteristics. The spatial distribution analysis based on topographical factors shows that Hakka traditional buildings are mainly distributed on slopes ranging from 5° to 15°. The main slope directions are northeast, southwest, and northwest, and the main elevations lie between 0 and 200 m. As the southeast of China was historically known as the “land of the barbarian”, indigenous peoples have long occupied most of the geographically favored areas in this region. Therefore, in order to avoid conflicts with the inhabitants and to protect their families, the Hakka people who migrated to southern Jiangxi and western Fujian had to choose remote areas such as jungle plains, basins, and hills to build large, enclosed homes for their families. When choosing settlements, the Hakka favored basins in mountainous environments and did not choose high-altitude areas. This concept of environmental adaptation stems from the inherited nature of Han culture and is influenced by the culture passed on by the Hakka ancestors.

Water is the source of life and an essential element in the daily production of human life. The water source, as an important factor for the Hakka people to find a place to live in the historical period, strongly influences the distribution of Hakka traditional architecture. Therefore, to facilitate their daily life and to meet their daily water needs, the Hakka ancestors chose to build their enclosed houses or earthen buildings closer to water sources. From the results of the previous analysis of water buffers in the Hakka region, 48.13% of the Hakka traditional buildings are located within 2.5 km of a water source; 25.13% of the Hakka traditional buildings are situated within 2.5–5 km of a water source; 73.26% of the Hakka traditional buildings are located within 5 km of a water source. This spatial distribution highlights the close relationship between Hakka traditional architecture and water sources, emphasizing the importance of water systems in shaping settlement patterns. Moreover, Hakka architecture in different regions exhibits distinct associations with specific water bodies. For instance, Hakka traditional buildings in Huizhou and Shenzhen are predominantly found along the Danshui River, while Hakka traditional buildings in Meizhou are clustered within the Ningjiang River watershed. Similarly, in Yongding, Hakka traditional buildings align with the Zhangxi River, and in Longnan, it is concentrated in the Taojiang River watershed.

Climatic influences on architectural style and distribution

The study results of Zhong et al. (2024) indicate that the atmospheric condition of the traditional villages is better compared to the social and ecological conditions. The Hakka region is located on the third terrace of China, affected by the alternating winter and summer monsoons, and has a subtropical monsoon climate. The area has hot summers and warm winters, with mild temperature, abundant rainfall, and sufficient heat. It is also a part of the hilly area in southeastern China, with complex topographical conditions and arable environment that provides good living conditions for the Hakka people. Even some Hakka traditional buildings collapsed and disappeared in long history due to age and disrepair after years of sun, wind, and rain exposure. However, it is also because of this relatively enclosed geographical situation that Hakka traditional architecture has survived fairly well through the ages. In the northern hemisphere, the south of the mountain is the sunny slope, and the north of the hill is the shady slope. The shady-sunny sides also affect the microclimate in this area. Combined with the distribution of Hakka traditional buildings on shady and sunny sides, the Hakka traditional buildings show an even distribution. It is the result of climatic conditions. Due to the overall low latitude and the subtropical monsoon climate in the Hakka area, there is not much difference between shady and sunny slopes. For this reason, the Hakka people did not consider the difference between shady and sunny slopes when selecting the site for their buildings. Natural factors such as topography, rivers, and sunlight influence the construction of settlements at regional and local levels (Tao et al., 2017).

Social factors in the formation of Hakka folk settlements

Influence of Hakkas migration

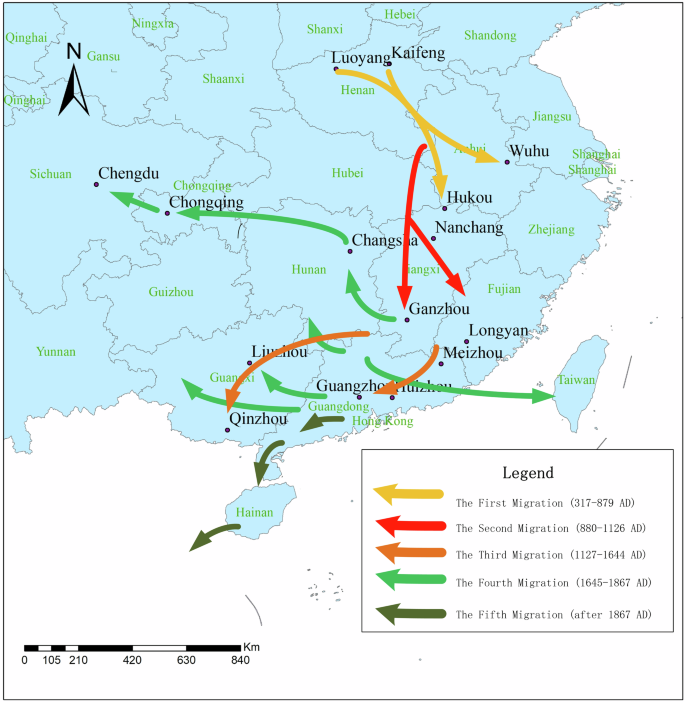

The migration of the Hakkas has been an epic journey in Chinese history. From the large-scale migrations during the Western Jin Dynasty and the An Lushan Rebellion in the Tang Dynasty, the Hakkas gradually established their unique culture and architectural style. Over time, the migration of the Hakkas did not cease. Following the fall of the Northern Song Dynasty and the invasion of the Jin army into the Central Plains, another large-scale migration southward occurred. Hakka traditional architecture began to emerge during the Song Dynasty and continued to develop through the Yuan and Ming periods. The Qing Dynasty marked the heyday of Hakka architecture, with a surge in the number of buildings and a diversity of styles that preserved the original Hakka architectural features while incorporating new elements. Later migrations saw Shenzhen and Huizhou emerge as important destinations for the Hakkas, further enriching the distribution and styles of Hakka architecture (Xi et al., 2021). These migrations not only expanded the geographical scope of Hakka culture but also profoundly influenced the evolution of Hakka architectural styles. The route of the Hakka people’s southward migration is also an important factor affecting the layout of Hakka traditional buildings. The main routes of the Hakka people’s southward migration can be summarized as follows: the central plains in the north—the Jiangnan area—the Ganjiang River basin—the border areas of Jiangxi, Fujian and Guangdong—the northeastern part of Guangdong—the central part of Guangdong—the western part of Guangdong, Guangxi and Taiwan (Fig. 13).

Map of Hakkas migration.

Influence of cultural beliefs on Hakka settlements

The formation of Hakka folklore and Hakka culture requires a significant population size. During the ancient period, the population of the Hakka region of Jiangxi-Fujian-Guangdong came mainly from the Central Plains in the north. Therefore, the migration of people from the north was, therefore, a crucial factor in the formation of the Hakka people. As an example of population change, the population of Ganzhou increased from 8994 households during the Tang Dynasty’s Zhenguan period to 26,260 homes during the Yuanhe period and from 86,146 households during the Song Dynasty’s Taiping Xingguo period to 321,356 households during the Baoqing period. In Fujian, there were 1690 households in Zhangzhou during the Kaiyuan period of the Tang Dynasty, 24,007 in the early Northern Song Dynasty, and 100,469 in the first year of the Song Dynasty. In Tingzhou, 4680 were in the Kaiyuan period of the Tang Dynasty, and 218,570 were in the Qing Yuan period of the Song Dynasty. In Guangdong, Meizhou had 1577 households in Song Taiping Xingguo and 12,370 in Song Chongning. In Xunzhou, 6891 were in Tang Zhenguan, and 47,192 were in Song Chongning. In Huizhou, 61,021 were in Song Yuanfeng. From the perspective of population changes, the period from the early Tang to the Song dynasties saw an increasing trend in the number of people living in the Hakka region (Ge, 1997).

Impact of traditional historical events on Hakka settlements

Regarding overall regional comparison, the Hakka region was still relatively underdeveloped until the early Tang Dynasty. During the Zhenguan period, in such a vast area of the Hakka region, there was only one state, Qianzhou, in the south of Ganzhou, with four counties under its jurisdiction. There was only one state, Xunzhou, in the east and northeast of Guangdong, with five counties under its jurisdiction, and there were few households in Qianzhou and Xunzhou. States and counties in Fujian’s southern and southwestern regions had not yet been established, so they were even more backward than those in southern Jiangxi and northeastern Guangdong. However, during the Tang and Song Dynasties, with the continuous southward migration of the population in the northern part of the Central Plains, the population of the Hakka areas in Jiangxi, Fujian and Guangdong increased significantly, providing greater scope for development. As can be seen from the administration’s establishment, Quanzhou, Zhangzhou, and Tingzhou were in southern and southwestern Fujian, and Chaozhou was in eastern Guangdong. As more states and counties were established, the number of households in the Jiangxi-Fujian-Guangdong regions continued to increase, reflecting the proliferation of the region’s population. All these phenomena reflect the economic and social progress and development of the region. Therefore, it provided extremely favorable economic and social conditions for the formation and development of Hakka settlements, with the larger population being the most important condition for the formation of Hakka folklore. During this period of about 300 years, from the end of the Tang Dynasty to the end of the Song Dynasty and the beginning of the Yuan Dynasty, the Hakka folk system gradually took shape. This was also the period when the Han Chinese immigrants in the adjacent areas of Fujian and Jiangxi were on a large scale.

Influence of ethnic group relations on the formation of Hakka settlements

The Hakka region in Jiangxi, Fujian and Guangdong is not a multi-ethnic area, and the ethnic minorities in the Hakka region are mainly the She and Yao. Some studies and analyses have shown that the Hakka of Guangdong is closely related to the She ethnic group (Luo et al., 2021). The Hakka areas in Jiangxi, Fujian and Guangdong were first inhabited by the She people before it became the Hakka settlement. Thus, the She people are the hosts, and the Hakka people are the guests. It is also through the integration of the Hakka and the She people in various aspects over a long period that the Hakka people have become what they are today. Therefore, the Hakka people are inextricably linked to the She people. The Hakka people were new to the area, but the original inhabitants were undoubtedly the masters of the site, and there have been several ‘Turk fights’ throughout history. For this reason, the Hakka people chose to live in clans. Because they were unfamiliar with the area, they decided to live in the jungles of the mountains with less favorable geographical environments. As the Hakka folk system developed over the years, large enclosed buildings began to be built. On the one hand, they were to facilitate contact between families. On the other hand, they were for self-defense. They were the reasons why the Hakka people constructed large, complex, layered, heavily walled, and very defensive dwelling structures.

Suggestions on the protection of Hakka traditional architecture

Based on the current state of Hakka traditional architecture, the following conservation recommendations are given.

-

(1)

Establish and improve a database of information on Hakka traditional architecture. A database of information on Hakka traditional architecture has been established by combining computer mapping techniques and geo-information technology to build a platform for visualization of Hakka traditional architecture. Computer mapping techniques are used to produce three-dimensional drawings of Hakka traditional buildings, showing the structural features of each Hakka traditional building through a 3D perspective (Hua et al., 2018). Geographic information technology is then used to store spatial-temporal data on Hakka traditional architecture and to visualize the location of Hakka traditional architecture on a map. From the two-dimensional map to the three-dimensional space, the Hakka traditional architecture can be presented more visually and three-dimensional, facilitating the recording, storage, and expression of information on Hakka traditional architecture.

-

(2)

Legislate to protect Hakka traditional architecture. Hakka traditional architecture is a cultural resource that cannot be replicated, and every Hakka traditional building is unique. However, Hakka traditional buildings have traveled through history, and many have slowly gone to ruin, gradually becoming crumbling. It is, therefore, necessary to pass legislation to preserve Hakka traditional architecture before most people have a strong sense of cultural preservation. Furthermore, on 26 February 2019, Ganzhou City held a press conference on implementing the Conservation Regulations for Hakka Buildings in Ganzhou and decided to formally implement them on 1 March 2019, protecting Hakka traditional architecture through legislation a reality. In a word, it is suggested here that the local governments draw on the legislative so that the Hakka traditional architecture can be better protected from the legal level.

-

(3)

Form a scientific management mechanism. The conservation of cultural resources and cultural heritage involves multifaceted matters, and therefore the conservation of Hakka traditional architecture also requires multi-sectoral cooperation and collaboration. It is recommended that each local government raise awareness of the protection of cultural resources, formulate a scientific conservation work plan according to the main responsibilities of each unit department, and establish a scientific and effective management mechanism. A working group should be set up in collaboration with various government departments to preserve Hakka traditional architecture. The working group collects specific information about the Hakka traditional buildings in their respective areas, regularly checks the condition of the Hakka traditional buildings, and reports them for repair on time. Hakka culture is a product of history and a treasure of Chinese culture. In the process of socio-economic development, Hakka traditional architecture should not be endlessly exploited, and should not get economic benefits at the expense of cultural resources.

The impact of our findings and prospects for further study

This paper analyzes the spatiotemporal distribution characteristics of traditional Hakka architecture from both qualitative and quantitative perspectives and explores the formation mechanism of Hakka folk settlements, which provides new study perspectives and methods for related disciplines. The analysis of geography, economic conditions, social structure, and historical background will help understand the formation of the architectural style. This paper also proposes the protection and management of Hakka traditional architecture, which provides feasible suggestions for cultural heritage protection and inheritance, helps promote Hakka culture, and guides the work of local government and related departments. In short, the study is of great significance for the study of Hakka culture and settlements, providing useful information and suggestions for academic study and practical application.

The results of this paper are similar to those of Lian and Li (2024) archeological study of architectural morphological features, which emphasized the importance of architectural morphological features in settlement formation. Consistent with Tao and Zhou (2024), the water system is a key factor that influences the settlement site selection decision. This suggests that geographical factors played an important role in the formation of ancient settlements. The research area selected for this study is a region where Hakka families from Jiangxi, Guangdong, and Fujian are concentrated and connected into blocks. Some Hakka areas, such as Guangxi and western Guangdong, also have traditional architecture. Therefore, in the future, the research area can be expanded to comprehensively and comprehensively carry out research on Hakka traditional architecture.

Conclusions

We took Hakka traditional architecture in southeastern China as an example, and comprehensively used geographical and mathematical statistical methods to explore the spatial distribution characteristics and formation mechanisms of Hakka folk settlements. The findings reveal a distinct clustering pattern, with Hakka buildings concentrated in five regions. This clustering is underscored by a theoretical average distance of 12.73 km, contrasting with the observed average distance of 6.8 km and an average nearest neighbor ratio (R) of 0.53, emphasizing the aggregation trend. Natural geographical conditions emerge as the predominant influence on the spatial distribution, with Hakka traditional architecture predominantly found in plains below 500 m altitude and slopes below 15°, mainly facing southwest and northeast. The availability of water resources and favorable climate further contribute to creating a conducive environment for Hakka farming and habitation. Beyond geographical factors, the distribution is shaped by Hakka culture, historical migration patterns, and ethnic and cultural considerations. The diligence, sincerity, and modesty ingrained in Hakka characteristics have facilitated adaptation to the intricate geographical landscape. Ultimately, this comprehensive exploration sheds light on the intricate interplay of geographical, cultural, and historical factors influencing the distribution of Hakka traditional buildings. The concentration of these architectural wonders in specific regions reflects not only the adaptability of the Hakka people but also the preservation of their cultural heritage amidst changing landscapes.

Responses