Factors associated with phenoconversion of idiopathic rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a prospective study

Introduction

Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) is a parasomnia characterized by loss of normal muscle atonia and dream enactment during REM sleep1. Idiopathic or isolated RBD (iRBD) is currently recognized as a critical prodromal stage with a high risk of progressing to α-synucleinopathies2,3,4. Previous studies have suggested that more than 80% of patients with iRBD could convert into Parkinson’s disease (PD), dementia of Lewy bodies (DLB), and multiple system atrophy (MSA) after years or decade2, indicating that iRBD may be an optimal target for early intervention and neuroprotective treatment. Previous case-control and retrospective cohort studies have shown that PD and its prodromal stage, e.g. iRBD, may share similar risk factors, including aging, genetic variants, some environmental exposures and lifestyle habits5,6,7,8. The facts that significant number of PD patients never had iRBD and iRBD patients progressed to α-synucleinopathies in a different rate or speed support the notion that there are specific factors might influence or contribute to the course of phenoconversion. Identifying those specific factors and development of intervention strategies could have significant impact not only in the understanding of the mechanisms of the diseases but also in modifying the disease course. However, these factors are yet poorly understood.

Although the cause of iRBD remains unknown, previous epidemiological studies have found that risk factors for PD or dementia, e.g. aging, gender, lower level of education9,10, head injury6,10, pesticide exposure6,8, farming6, and carbon monoxide (CO) poisoning8, were also associated with increased risk for iRBD. In contrast, there were also lifestyle factors uniquely identified for increased risk for iRBD but not PD, e.g. smoking8,9 and alcohol use9. Regarding the risk factors for phenoconversion to α-synucleinopathies in iRBD, only two longitudinal studies in the same multicenter cohort have investigated whether these factors play a role in the progression and phenoconversion at 4 years and 11 years follow-up11,12. According to the studies, certain factors including age, rural living, prior pesticide exposure, nitrate derivative use, lipid-lowering medication use, and respiratory medication use, were demonstrated to affect the phenoconversion of iRBD. Nonetheless, the majority of the patients in the previous studies were from Europe and North America, and variations in environments and lifestyles exist among nations and regions. Specifically, tea drinking as a protective effect was mostly found in Asians but not Caucasian13,14. Therefore, the current study aimed to investigate the relationship between environmental/lifestyle factors and the conversion of iRBD to α-synucleinopathies in a prospective RBD longitudinal cohort in China.

Results

Participants and disease outcomes at follow-up

Among 155 patients with iRBD in our cohort. 141 (90.97%) participants fulfilled the inclusion criteria and were included in the current study. 14 subjects were excluded from the analysis, including 7 patients lost in follow-up, 2 patients died of other diseases before the first follow-up, and 5 patients recruited less than one year. 11 of 141 participants died after the last follow-up and were included in the analysis. The mean follow-up time (from baseline to the last interview) was 4.14 ± 2.88 years.

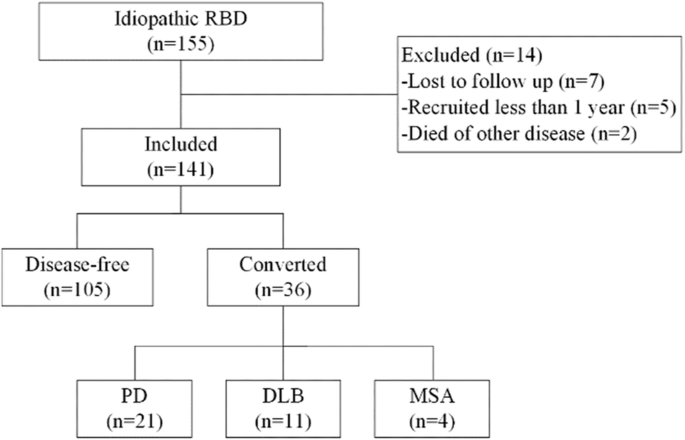

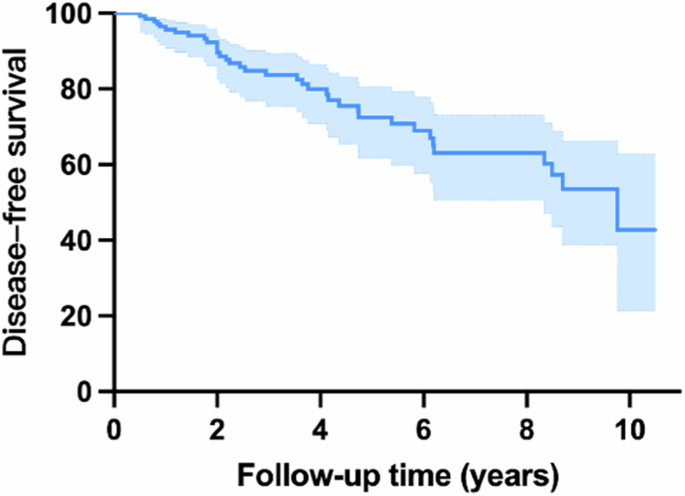

During follow-up, 36 (25.53%) patients developed α-synucleinopathies (PD, DLB, MSA), and 105 (74.47%) patients remained disease-free till the last visit or before death (Fig. 1). The mean interval from the baseline interview to the disease phenoconversion is 3.59 ± 2.53 years. The cumulative incidences were 16.30% after 3 years, 27.57% after 5 years, 57.20% after 10 years (Fig. 2). The diagnosis included PD in 21 patients (58.33%), DLB or dementia in 11 patients (30.56%), and MSA in 4 patients (11.11%).

Of the 155 enrolled iRBD, 14 were excluded and 141 were included in the final analysis. Thirty-six patients converted to α-synucleinopathies, including 21 PD, 11DLB, and 4 MSA. PD Parkinson’s disease, DLB dementia of Lewy bodies, MSA multiple system atrophy.

The cumulative incidences were 16.30% after 3 years, 27.57% after 5 years, 57.20% after 10 years.

Demographics, environmental and lifestyle factors

As shown in Table 1, at the baseline, the mean age of iRBD patients was 66.66 ± 7.13 years old and 104 (73.76%) of the patients were male. The average duration of iRBD symptoms was slightly longer (p = 0.048) in the converters (9.17 ± 7.92 years with a median duration of 7 years) than in non-converters (6.16 ± 7.01 years with a median duration of 3.25 years). Age, sex ratio, educational levels, and follow-up years were not significantly different between iRBD converters and non-converters.

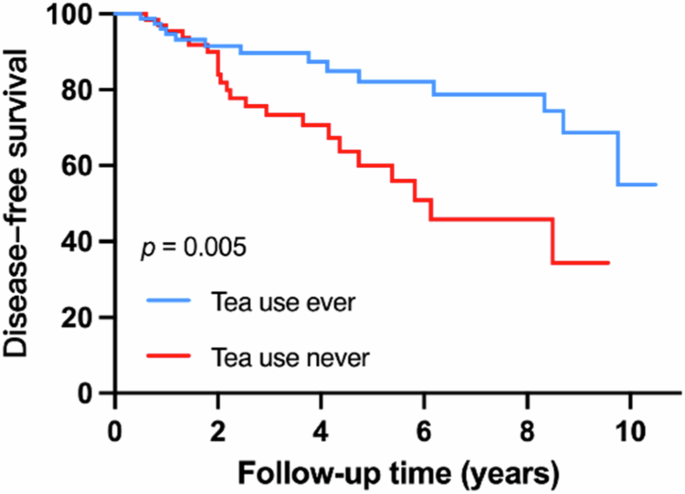

In general, no association was observed between environmental exposures and disease phenoconversion. For lifestyle habits, iRBD patients who had drunk tea ever had a two-fold lower risk of converting to α-synucleinopathies (adjusted HR = 0.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.17–0.73, p = 0.005) (Fig. 3). Those who keep the habit of drinking tea and drinking daily exhibited a similar lowered risk for phenoconversion (adjusted HR = 0.34, 95% CI = 0.16–0.74, p = 0.007, and adjusted HR = 0.32, 95% CI = 0.14–0.72, p = 0.006 respectively). Although the analysis model for factors of RBD conversion was adjusted for the duration of RBD symptoms, the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale Part III (UPDRS-III) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) were adjusted for the results to further reduce the influence of mild motor symptoms and cognitive impairment on the period of conversion between conversion and non-conversion groups. The results of risk factors were similar to those of the primary analyses (Supplementary Table S1). However, no association between the total amount of tea consumed and conversion risk was observed though non-converters drank more cups/w-years of tea than converters. Still, the difference was not statistically significant (327.82 ± 535.24 vs 272.10 ± 605.27, p = 0.337).

IRBD patients with tea use history had lower risk of developing α-synucleinopathies (adjusted HR = 0.35, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.17–0.73, p = 0.005).

None of the ever-smoking, current-smoking, and pack-years was associated with disease phenoconversion. Drinking alcohol ever and currently was not associated with disease conversion. Converters had slightly more but not statistically significantly drinking servings/week-years than non-converters (185.50 ± 370.39 vs 176.03 ± 392.50, p = 0.151). In addition, there was no statistically significant association between coffee use or exercise and phenoconversion.

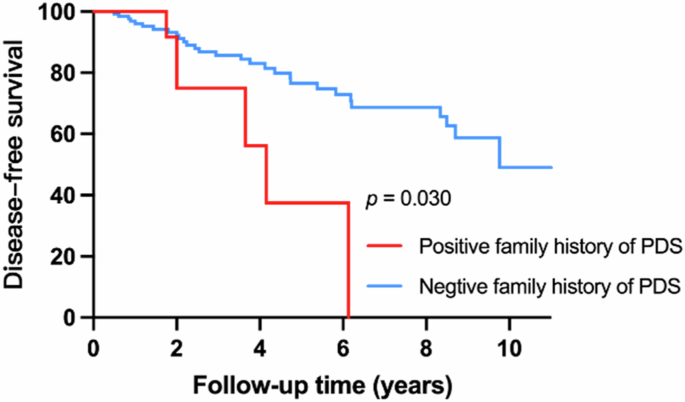

Family History of Parkinsonism and dementia

A greater risk of developing α-synucleinopathies was found in patients with a positive family history of parkinsonism (adjusted HR = 2.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.11–7.06, p = 0.030) (Fig. 4). There was no discernible variation in the positive family history of dementia between converters and non-converters.

IRBD patients with positive family history of parkinsonism had increased risk of developing α-synucleinopathies (adjusted HR = 2.79, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.11–7.06, p = 0.030).

Comorbidity and Medication History

In terms of comorbidities, no statistically significant differences were found in self-reported hypertension, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, hyperthyroidism, stroke, encephalitis, epilepsy, and depression/anxiety between converters and non-converters (Supplementary Table S2). Neither was observed in the use of antihypertensive agents, β-blockers, calcium channel receptor antagonists, antidiabetic drugs, uric acid-lowering drugs, lipid-lowering drugs, antiplatelet drugs, antidepressants, melatonin and melatonin receptor agonists, and clonazepam.

Discussion

The current study demonstrated that most known risk factors for PD and iRBD were not associated with an increased risk for phenoconversion from iRBD to a-synucleinopathies. However, iRBD patients with ever tea drinking had a two-fold decrease in risk of being converted, while a positive family history of parkinsonism had a two-fold increase in risk for conversion. Our finding suggests that tea drinking may specifically modify the disease progression and reduce the risk for or delay phenoconversion, at least in Chinese.

Previous studies have shown that factors associated with increased risk for PD, e.g. aging11,12, gender15, CO poisoning8, and pesticide exposure6,7,8, are also risk factors for iRBD and its progressing to clinical manifestation. Interestingly, when our prospective study specifically comparing the iRBD patients with and without phenoconversion to α-synucleinopathies during follow-up, most factors associated with increased risk for both PD and iRBD were not significantly associated with a faster rate of conversion except duration of iRBD. These findings suggest that these risk factors may be only associated with overt dopaminergic degeneration but not accelerated conversion from iRBD to α-synucleinopathies. However, this notion needs to be validated in future studies with a large sample size.

Consistent with the previous multicenter study in iRBD11, we found a close relationship between a positive family history of parkinsonism and clinical phenoconversion. In fact, studies have shown that patients with RBD partially share some of the genetic background of PD and DLB, including SCARB2 (rs6812193), MAPT (rs12185268)5, GBA16, and SNCA variants17. Moreover, iRBD with GBA18 or SNCA17 variants were reported to potentially correlate with the rate of conversion to synucleinopathies. Therefore, genetic risk factors may play a role not only in the development of iRBD but also in its phenoconversion. Our previous study has shown that PD patients with LRRK2 and GBA risk variants had a higher likelihood ratio and fast conversion19. Further studies are needed to clarify the role of genes in disease fast conversion.

The key finding of this study is that iRBD patients with a history of tea consumption were less likely to be converted, suggesting that present or daily tea drinking may slow the disease progression. Tea consumption was first found to reduce the risk of PD in a study with the Chinese population in 199820. Following that, many studies from different regions have investigated if tea exerts a protective effect on PD with different conclusions13,21,22,23,24. Although most studies in the Caucasian population found a negative results, there was one study found that tea drinking had a protective influence on LRRK2 mutation carriers in non-Asians25. Therefore, these studies support the notion that tea drinking has protective effects in individuals with increased risk for PD, particularly in populations with regular habits of tea drinking in Asian.

The exact mechanism of the possible protective role of tea on iRBD progression is still unclear. Some scholars believe that it was caffeine that has an antagonistic effect on adenosine A2A receptors that act as a part22,23. Others thought that it was tea polyphenols rather than caffeine that were responsible for the protective effect against dopaminergic neurotoxicity and modification of oxidative stress21,24. A prior study has demonstrated that tea polyphenols protect against dopamine (DA)-related toxicity through direct abrogation of DA-induced toxicities as well as regulation of anti-oxidative signaling pathways in vitro and in vivo PD models26. Moreover, a study suggested that fermented tea had therapeutic value in an MPTP-induced PD mouse model for its anti-neuroinflammatory, anti-apoptosis, antioxidant, and neuroprotective properties27. In contrast, no difference in baseline caffeinated tea consumption between converters and non-converters in patients with iRBD was also reported12. The disparity could be attributed to a variation in diet culture differences between the West and the East. It is known that coffee intake is more common in Caucasians but Chinese prefer drinking tea28, which is consistent with a low percentage of patients with iRBD who drank coffee in this study. Moreover, no association between coffee intake and RBD phenoconversion was found in the previous study12. Therefore, we consider that the caffeine component of tea may not be the main reason for its effect on disease conversion. Accordingly, the protective effect of tea consumption in iRBD may provide prospects for α-synucleinopathies prevention and serve as the foundation for future interventional trials.

It was suggested that lower PD risk and smoking had a dose-response relationship29. Meta-analysis also showed substantial evidence that smokers are less likely to develop PD30. However, a previous study has found that smoking, on the other hand, is a potential risk factor for iRBD6. In addition, no link was reported between smoking and phenoconversion risk in a large multicenter RBD study12, which is similar to our finding. Therefore, smoking is less likely associated with phenoconversion.

In terms of comorbidities and medications, contrary to our results, previous studies found that β2-adrenoreceptor agonists12, nitrate derivatives12, lipid-lowering drugs12, and antidepressants31 were associated with phenoconversion of iRBD. This might be due to variations in the time and dosage of medication used in the studies.

Several limitations in this study should be noted. First, it was a single-center study of the Chinese population and could not represent the general population. Second, patients’ reports on environment and lifestyle exposures were based on their subjective recollection, which could lead to recall bias. Third, the questionnaire for assessing physical activity in this manuscript was custom-made instead of established. Fourth, we paid more attention to the amount and frequency of tea consumed but did not inquire about specific classifications of tea (green, black, or others). It is likely most people drink different types of tea rather than fixed types. Finally, some environmental exposures and lifestyle factors were reported only in fewer patients, such as pesticide exposure, weakening the power of the statistics. Therefore, future multicenter prospective investigation is warranted.

In conclusion, our prospective study found that iRBD with a positive family history of PDS had a higher risk for conversion to α-synucleinopathies, while tea drinking was associated with a decreased risk for phenoconversion. Although the mechanistic aspects may not be elucidated in this study focusing on the assessment of risk associations, its results shed light on its potential application in disease-modifying effects of tea drinking for phenoconversion of iRBD.

Methods

Subjects

Subjects aged 50 years or older with iRBD were consecutively recruited from the Department of Neurology at Xuanwu Hospital Capital Medical University from October 2012 to October 2022. All patients were diagnosed based on video-polysomnography (v-PSG) and met the International Classification of Sleep Disorders-3 criteria32 for RBD. Individuals diagnosed with secondary RBD, such as those associated with narcolepsy, brainstem lesions, or medication use (mostly antidepressants) were excluded. A thorough neurological evaluation was performed on each participant to rule out the presence of any symptoms or signs of dementia or parkinsonism. By October 2022, 155 patients with iRBD were included in this study.

Baseline questionnaires

A standardized structured questionnaire was designed to assess the presence of environmental exposure and lifestyle habits at baseline interview. Demographic information was collected, including gender, age, and education levels. Duration of RBD symptoms and family history of parkinsonism or dementia were reported by patients or their family members. RBD Questionnaire-Hong Kong (RBDQ-HK), the UPDRS-III, and MoCA scores were obtained through face-to-face interviews by physicians. Histories of CO poisoning, head injury, and exposures to noxious agents, chemical solvents, heavy metals, chemical aerosol, trichloroethylene, rotenone, and paraquat were collected. Lifestyle variables were also collected for smoking history, alcohol consumption, tea and coffee intake, and exercise status. The quantity of cigarettes daily use, years of smoking, the number of cups of alcohol, tea, and coffee consumed weekly and duration were recorded. The number of packs smoked every day (20 cigarettes per pack) multiplied by the number of years smoked was used to calculate pack-year. Cups/week–year was calculated by multiplying the average number of cups per week by the number of years for consuming tea or coffee. Servings/week-year was calculated by multiplying the average number of servings per week by the number of years of drinking alcohol. For reference, a serving is a can or bottle of beer, a glass of wine, or a shot of liquor. Smoking or drinking beverages were categorized as “ever” (past and current) and “never”. Participants who had smoked fewer than 100 cigarettes (five packs) or drank alcohol less than 100 times by the time of the questionnaire were considered as “never”. Those who did not drink tea or coffee at least once a week for six months were defined as never drinking. The status of smoking and drinking (alcohol, tea, coffee) were divided into “past”, “current” and “never”. The frequency of tea drinking and physical exercise, as well as exercise types (cycling, running, boxing, dancing, hiking, walking, and others), were also collected. Information about previous medical histories of hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD), hyperthyroidism, stroke, encephalitis, epilepsy, depression, and anxiety were obtained. Besides, history of medication using antihypertensive agents, β-blockers, calcium channel receptor antagonists, antidiabetic drugs, antipsychotic drugs, antiplatelet drugs, antiepileptic drugs, antidepressants, melatonin, and melatonin receptor agonists, clonazepam were also collected in the baseline assessment.

Follow-up and phenoconversion

We prospectively followed up subjects with iRBD by in-person interview or telephone interview. The phenoconversion to define parkinsonism or dementia was diagnosed by at least two experienced movement disorder specialists. In our cohort, only iRBD patients underwent at least one follow-up more than one year after the baseline assessment were included in the current analysis. The date of the last visit and the onset time before the final diagnosis of neurodegenerative diseases were recorded. For patients with parkinsonism-first manifestations, clinical diagnoses of PD or MSA were made according to the diagnostic criteria described by the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) and Gilman et al., respectively33,34. For patients with dementia-first manifestations, the diagnosis of DLB was based on the consensus criteria35,36, depending on the conversion year. If both parkinsonism and dementia were diagnosed at the same visit, the diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease dementia (PDD) or DLB would be established according to the one-year principle. It should be noted that mild cognitive impairment (MCI) was not considered a phenoconversion in this study.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants. The protocols of this study have been approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University (Ethics approval No. [2012]006, No. [2022]047).

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 25.0 (IBM, Corp.) was used for statistical analysis. For descriptive statistics, continuous variables were summarized as mean ± standard deviation (SD), whilst categorical variables were presented as frequencies (percentages). We conducted comparisons between groups of baseline characteristics using an unpaired two-tailed Student t-test or the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. For categorical variables, the χ2 test was used. We performed Cox proportional hazard analysis to evaluate the variables of environmental and lifestyle factors between those who phenoconverted to α-synucleinopathies and those who remained iRBD, adjusted for age, sex, and iRBD duration.

Responses