Fish oil-loaded silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized emulsions with vitamins for the delivery of curcumin

Introduction

The emulsion is an excellent system to encapsulate and deliver liposoluble curcumin. As a natural low-molecular-weight polyphenol nutrient, curcumin has been widely acknowledged for its anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and antioxidant activities for human beings1. However, the poor water solubility and low bioavailability restrict the potential application of curcumin2. Emulsion is a promising delivery system to overcome these challenges of curcumin3. The type of interfacial materials is one of the key factors to affect the delivery behaviors of the curcumin-loaded emulsion1. Therefore, novel interfacial materials have attracted much attention to develop curcumin-loaded emulsions.

Gelatins are valuable proteins for food and pharmaceutical industries. They were extracted by partial hydrolysis of collagens in several tissues (e.g., skin and scale) of many animals (e.g., mammalian and fish)4. Silver carp scale is a common by-product in the fish industry because silver carp is the best freshwater fish for surimi production5. Fish scale gelatins have been developed and applied as biomaterials for tissue engineering6, food packaging materials7, biomaterials for nutrient loading8, artificial fish bait9, etc. Our group previously found that silver carp scale gelatin could be applied to stabilize fish oil emulsion10. Further research has not been explored such as nutrient encapsulation and delivery. The development of fish oil emulsions stabilized by silver carp scale gelatin would provide a useful guide for the value-added utilization of fish by-products.

Vitamins C (VC) and E (VE) are important micronutrients with excellent antioxidant properties. They have many health-promoting effects such as the improvement of immune function11 and the prevention/treatment of cancer12. Therefore, VC and VE are important nutrients and antioxidants for food development. Our group previously found that VC and VE could increase the stability of fish oil-loaded emulsions stabilized silver carp scale gelatin13. However, the effects of VC and VE on properties of curcumin-loaded emulsions have not been explored such as the lipid oxidation, curcumin contents and retention, and in vitro digestion behaviors. The results would provide useful information for the development of vitamins/curcumin-loaded emulsions.

This study aimed to explore fish oil-loaded silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized emulsions with vitamins for the delivery of curcumin. First, the formation of hot water-pretreated silver carp scale gelatin (HWSCG)-stabilized curcumin/fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins was studied. Second, the stability of HWSCG-stabilized curcumin/fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins was analyzed. Third, the lipid oxidation of HWSCG-stabilized curcumin/fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins was investigated. Fourth, the curcumin contents and retention of HWSCG-stabilized curcumin/fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins were determined. Finally, the in vitro digestion behaviors of HWSCG-stabilized curcumin/fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins were measured including free fatty acid (FFA) release, curcumin transformation, curcumin bioaccessibility, and curcumin bioaccessibility index. The results would provide a useful guide for the value-added utilization of fish by-products and useful information for the development of vitamins/curcumin-loaded emulsions.

Results and discussion

Formation of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins

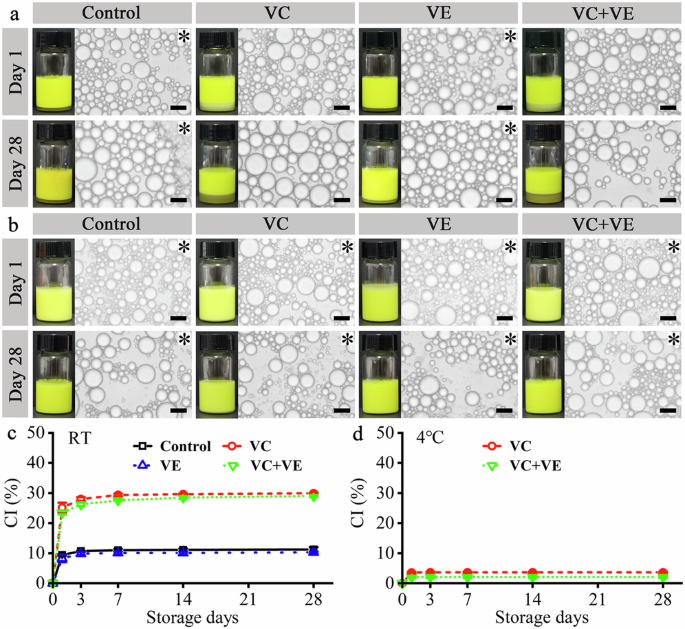

HWSCG was extracted using a hot water-pretreated method and freeze-dried to obtain dried HWSCG10. The HWSCG was used to stabilize curcumin/fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins (VC, VE, and VC + VE). Because of the encapsulation of curcumin14, all the emulsions with or without vitamins showed yellow color (Fig. 1a). All the emulsions consisted of microscale droplets, as shown in the optical microscopy images in Fig. 1a. Moreover, all the emulsions consisted of trimodal microscale droplets (Figs. 1b–3) and vitamins had no obvious effects on the curcumin/fish oil-loaded HWSCG-stabilized emulsions, which accorded with fish oil-loaded silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized emulsions with vitamins13. Therefore, the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the formation of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins.

a Digital camera and optical microscopy images. Black scale bars represent 20 μm. b–e Representative droplet size fitting for the statistical droplet sizes in the emulsions.

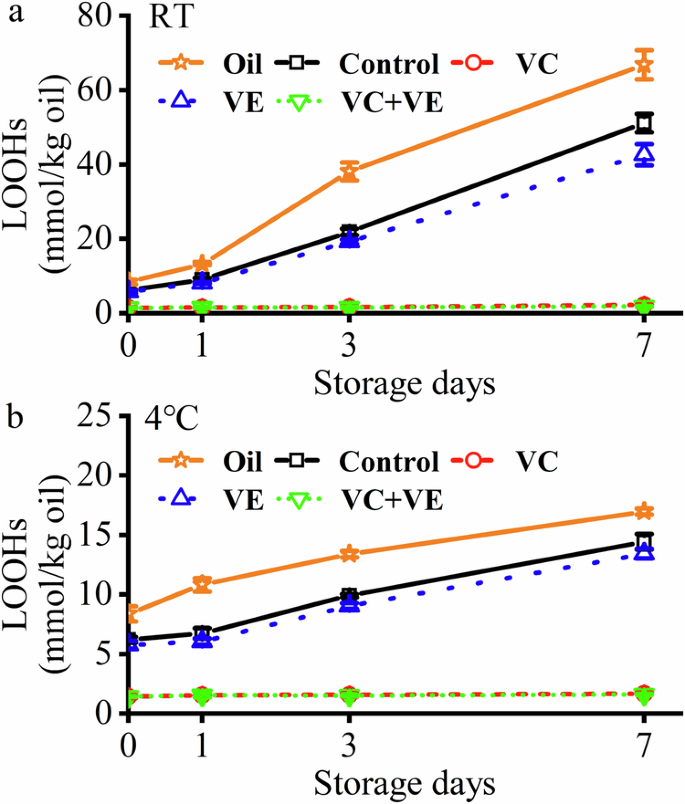

a Digital camera and optical microscopy images of the emulsions at room temperature (RT) after one-day and 28-day storage. b Digital camera and optical microscopy images of the emulsions at 4 °C after one-day and 28-day storage. Black scale bars represent 20 μm in the optical microscopy images. The emulsion gels are indicated with black asterisks in the optical microscopy images. c Creaming index (CI) values of the emulsions during the RT storage. d CI values of the emulsions during the 4 °C storage.

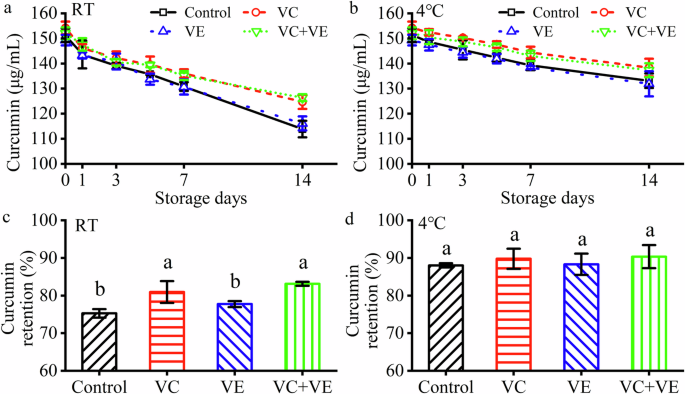

a During the 7-day storage at RT. b During the 7-day storage at 4 °C. Orange pentagrams indicate pure fish oil.

Stability of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins

The curcumin/fish oil-loaded HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with VC and/or VE were incubated for 28 days, as shown in Figs. 2 and S1. All the emulsions consisted of spherical droplets during the storage at RT (Figs. 2a and S1a) and 4 °C (Fig. 2b and S1b), which was different from the deformed droplets in the bovine bone gelatin-stabilized emulsion after 30-day storage at 4 °C15. With time, the emulsion droplet sizes at RT storage showed a slight increase, which was generally caused by droplet coalescence in the storage process16. Interestingly, the emulsion droplet sizes at 4 °C storage showed no obvious changes.

The liquid emulsion can be converted to emulsion gel via liquid-gel transition during storage17. Gelatin could self-assemble to gels at low temperatures via the formation of helices structure18, and therefore, gelatin-based emulsion gels might be prepared by incubating the liquid emulsions at <30 °C. At RT (Fig. 1a), the liquid emulsions with VC (VC and VC + VE groups) did not become gels even on day 28, whereas other emulsions became gels on day 1. At 4 °C, all the emulsions became gels on day 1 (Fig. 2b). Therefore, VC addition slowed the liquid-gel transition, and low-temperature (4 °C) incubation speeded the liquid-gel transition. They were consistent with the behaviors of silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions13. Therefore, the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the liquid-gel transition of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins.

The creaming stability of the emulsions was dependent on the incubation temperature and vitamin addition. The control sample (Curcumin/fish oil-loaded HWSCG-stabilized emulsion) showed creaming index (CI) values of 11.3% ± 0.7% at RT (Fig. 2c) and 0 at 4 °C (Fig. 2d), which were similar to that of silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions13. In addition, the VE group showed slightly lower CI values than the control group at RT and a similar CI value (0) to the control group at 4 °C. The VC and VC + VE groups showed higher CI values than the control group at RT and 4 °C. These results suggested the presence of VC decreased the creaming stability of curcumin/fish oil-loaded HWSCG-stabilized emulsion, which were consistent with the behaviors of silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins13. Therefore, the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the creaming stability of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins.

Lipid oxidation of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins

The lipid hydroperoxide (LOOH) of the emulsions at RT and 4 °C were measured to analyze the lipid oxidation behaviors of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins (Fig. 3). The emulsions except VC and VC + VE groups showed increasing LOOHs with time. Moreover, obvious LOOH differences were shown among these groups in 7 days. Therefore, LOOHs were only measured for 7 days. Compared with pure fish oil (Day 7 at RT: 66.8% ± 3.9%; Day 7 at 4 °C: 16.9% ± 0.3%), the emulsion preparation (control group) reduced the LOOH values (Day 7 at RT: 51.2% ± 2.5%; Day 7 at 4 °C: 14.4% ± 0.7%), indicating that the emulsion encapsulation delayed the oxidation of oil. Further, the both VC and VE addition reduced the LOOH values: VC + VE (Day 7 at RT: 1.8% ± 0.1%; Day 7 at 4 °C: 1.6% ± 0.1%) < VC (Day 7 at RT: 2.2% ± 0.1%; Day 7 at 4 °C: 1.7% ± 0.1%) < VE (Day 7 at RT: 42.6% ± 2.9%; Day 7 at 4 °C: 13.4% ± 0.4%) < Control < Pure fish oil. The effects of emulsion preparation, vitamin addition, and incubation temperatures were consistent with the behaviors of silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions with vitamins13. Therefore, the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the lipid oxidation of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins.

Previous work suggested VC and VE had a synergistic effect on lipid peroxidation. Some in vitro studies indicated that VC could enhance the antioxidant effect of VE by reducing VE radicals19,20. VC and VE showed a synergistic effect on lipid peroxidation in liposome21. The in vivo animal studies suggested VC and VE acted synergistically on lipid peroxidation22. The in vivo human randomized controlled trial suggested VC and VE had no synergistic effect on lipid peroxidation23. Therefore, the synergistic effect of VC and VE might be dependent on the enviroments. In this work, VC and VE showed a synergistic effect on the peroxidation of the oil core in the emulsion systems (Fig. 3). The water-solubule VC and lipid-soluble VE were present in the water phase and oil core, respectively. Therefore, the possible reason was that VC enhanced the antioxidant effect of VE for lipid peroxidation in the oil core.

Curcumin contents and retention of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins

Curcumin has good degradation resistance in oils and bad degradation resistance in aqueous solutions24. Curcumin degradation mainly occurs in the water phases of the oil-in-water emulsions. The curcumin in the oil phase could be exchanged to the water phase and then degraded in the water phase25. Therefore, curcumin contents and retention with time is an important characteristic of a curcumin-loaded emulsion.

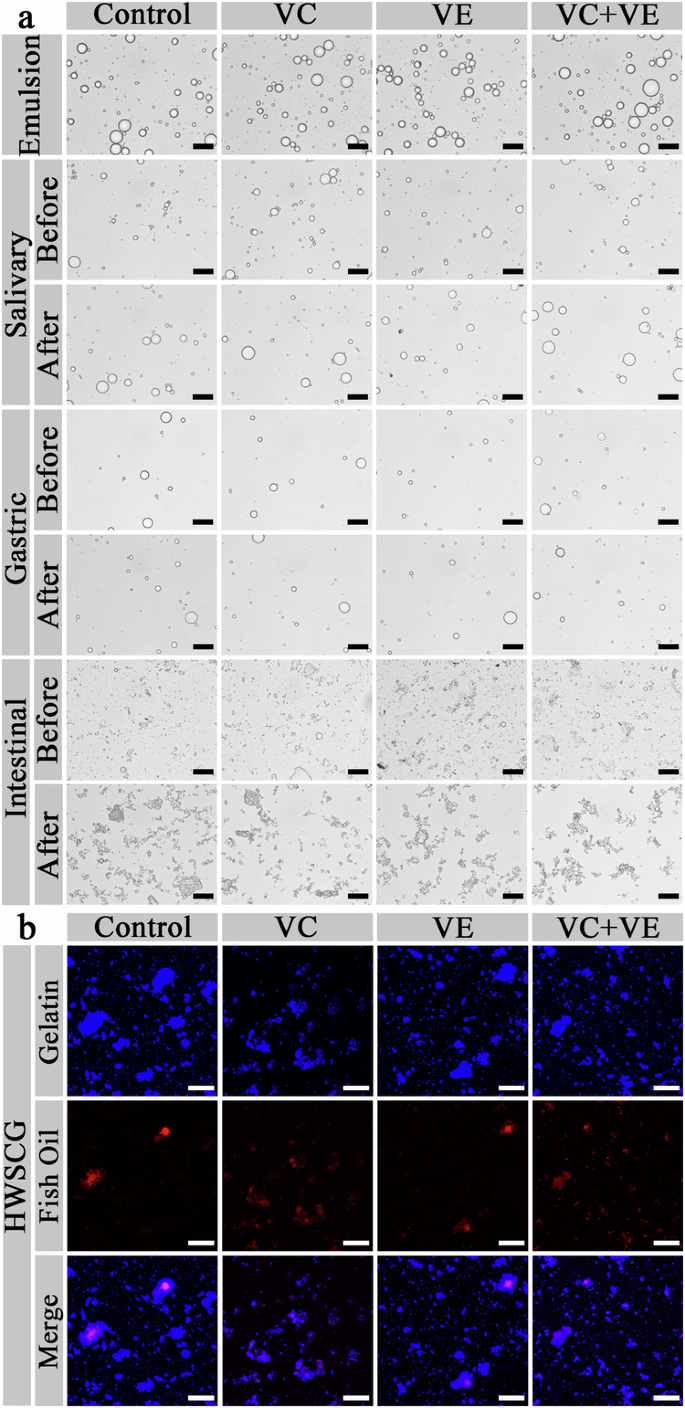

All the initial curcumin contents of the HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins were about 150 μg/mL (Fig. 4a, b). Due to the curcumin degradation24,25, the curcumin contents of all the emulsions decreased with the increase of incubation time (0–14 days) at RT (Fig. 4a) and 4 °C (Fig. 4b). All emulsions showed decreasing curcumin contents with time. Moreover, obvious curcumin content differences were shown among these groups in 14 days. Therefore, curcumin content were only measured for 14 days.The curcumin contents were dependent on vitamin additions (Fig. 4a, b): VC + VE ≈ VC > VE ≈ Control. The curcumin retention after 14 days at RT showed obvious vitamin dependence (Fig. 4c): VC + VE (83.1% ± 0.6%) ≈ VC (80.9% ± 2.9%) > VE (77.7% ± 0.8%) ≈ Control (75.3% ± 1.1%). The curcumin retention after 14 days at 4 °C no significant differences (Fig. 4f): VC + VE (90.3% ± 3.1%), VC (89.8% ± 2.7%), VE (88.3% ± 2.8%), and Control (88.0% ± 0.6%). However, the average values of the curcumin retention after 14 days at 4 °C also showed obvious vitamin dependence. Therefore, VC addition could increase the curcumin retention in the emulsions, whereas VE had no obvious effect on the curcumin retention in the emulsions. Moreover, low-temperature storage could increase the curcumin retention in the emulsions.

a Curcumin contents at RT. b Curcumin contents at 4 °C. c Curcumin retention after 14-day storage at RT. d Curcumin retention after 14-day storage at 4 °C. The different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in each image.

Vitamins had different effects on the curcumin retention in the emulsion. VC and VE significantly increased and slightly decreased, respectively, the curcumin retention in oil-in-water emulsions after storage with the increase of VC concentrations26. It suggested the curcumin degradation might occurred within the aqueous phase and close to the oil/water interface. Therefore, VC could pretect curcumin by scavenging more free radicals that initiate curcumin degradation or donating more protons to the curcumin radical to regenerate curcumin. Moreover, VE addition had no obvious effect on the curcumin retention after storage.

In vitro digestion behaviors of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins

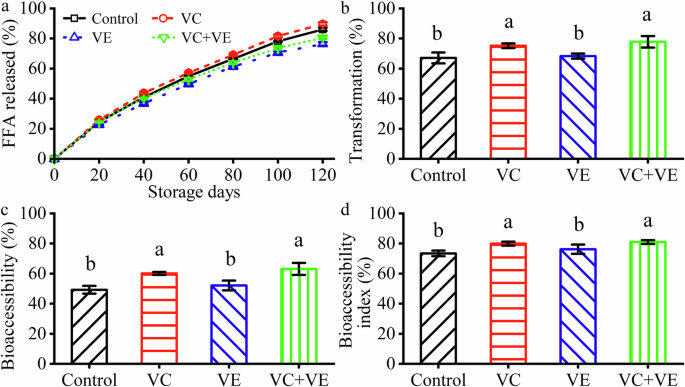

The curcumin/fish oil-loaded HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with VC and/or VE were treated in a simulated human gastrointestinal tract system with simulated salivary fluid (SSF), simulated gastric fluid (SGF), and simulated intestinal fluid (SIF). Then, the microscale behaviors, FFA released behaviors, and curcumin behaviors (transformation, bioaccessibility, and bioaccessibility index) of the emulsions were analyzed, as shown in Figs. 5 and 6.

a Optical microscopy images. Black scale bars represent 20 μm. b Confocal laser scanning microscopy images. White scale bars represent 25 μm.

a Free fatty acid (FFA) release percentages. Black squares indicate the control emulsions. b Curcumin transformation. c Curcumin bioaccessibility. d Curcumin bioaccessibility index. The different letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in each image.

The microscale emulsion droplets were observed with optical microscopy and confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM) (Fig. 5). After 10× dilution, no obvious effect was shown on the emulsion droplet shape, which was consistent with the effect of dilution on the gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions27. The emulsion droplets appeared in the SSF (Fig. 5a: Salivary) and SGF (Fig. 5a: Gastric) phases. The pH was not changed during the whole SGF phase. The emulsion droplets disappeared in the SIF phase, as shown in the optical microscopy (Fig. 5a: Intestinal) and CLSM (Fig. 5b) images. According to these results, we could conclude that the emulsion droplets were mainly digested and fish oil was released in the SIF phase, which was consistent with the droplet digestion of silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions13. So, the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the in vitro microscale droplet digestion of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins.

The FFA released behaviors were analyzed in the SIF phase, as shown in Fig. 6a. After the SIF phase, the accumulative released FFA percentages were dependent on the vitamins: VC (89.6% ± 1.1%) > Control (86.1% ± 1.0%) > VC + VE (80.5% ± 0.8%) > VE (76.4% ± 1.2%). It was consistent with that VC increased, whereas VE and VC + VE decreased the released FFA percentages of silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized fish oil-loaded emulsions13. Therefore, the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the microscale droplet digestion of HWSCG-stabilized emulsions with vitamins. FFA was released from the degradation of triglycerides with lipase28. Water-soluble VC and fat-soluble VE might increase and decrease, respectively the activility of lipase. Therefore, they increased and decreased, respectively, the accumulative released FFA percentages in the SIF phase.

After the SIF phase, the curcumin transformation was dependent on the vitamins (Fig. 6b): VC + VE (77.8% ± 3.8%) ≈ VC (75.2% ± 1.6%) > VE (68.4% ± 1.7%) ≈ Control (67.1% ± 3.7%). The relationship was consistent with the curcumin retention during the storage at RT (Fig. 4a, c). The values were higher than those of the curcumin-loaded liposomes29. Therefore, HWSCG-stabilized emulsions were good carriers for curcumin transformation.

After the SIF phase, the curcumin bioaccessibility and bioaccessibility index of the emulsions were dependent on the vitamins (Fig. 6c, d): VC + VE (63.1% ± 4.0% and 81.0% ± 1.3%) ≈ VC (60.1% ± 1.0% and 79.9% ± 1.4%) > VE (52.1% ± 3.3% and 76.2% ± 3.1%) ≈ Control (49.3% ± 2.6% and 73.4% ± 1.9%). The relationship was consistent with the curcumin retention during the storage at RT (Fig. 4a, c) and the curcumin transformation (Fig. 6b). The bioaccessibility values were between the highest (about 65%) and lowest (about 20%) bioaccessibility of the curcumin-loaded liposomes29. Therefore, HWSCG-stabilized emulsions were good carriers for curcumin bioaccessibility.

Previous review summarized that the curcumin delivery behaviors in the emulsions were dependent on the dispersion conditions of curcumin in the oil phase, oil composition, emulsion droplet size, volume fraction, and the type of interfacial materials1. This work suggested that antioxidant additive was also an important factor and VC could increase the transformation, bioaccessibility, and bioaccessibility index of curcumin in the HWSCG-stabilized emulsions (Fig. 6c, d).

In this work, fish oil-loaded silver carp scale gelatin-stabilized emulsions with vitamins were explored for the delivery of curcumin. All results suggested the encapsulation of curcumin did not affect the formation, storage stability, lipid oxidation, in vitro droplet digestion behaviors of the emulsions. Moreover, VC addition could increase the retention during the storage, and the transformation, bioaccessibility, and bioaccessibility index of curcumin after the in vitro simulation digestion process. This work provided useful information to develop and apply fish oil-loaded fish gelatin-stabilized emulsions with vitamins for the delivery of curcumin. Moreover, this work provided a useful guide for the value-added utilization of fish by-products and useful information for the development of vitamins/curcumin-loaded emulsions for functional foods.

Further research is necessary to deepen the development and application of fish oil-loaded fish gelatin-stabilized emulsions with vitamins for the delivery of curcumin. First, the detailed molecular mechanisms should be illustrated for the delivery of curcumin in the emulsions with vitamins. Second, the effect of tissue sources and fish sources on the properties of curcumin emulsions should be explored. Third, the influence of environmental factors (pH, ionic strength) on emulsion stability should be investigated to better understand the in vitro digestion. Finally, more antioxidant agents should be explored to improve the curcumin delivery in the emulsions.

Materials and methods

Reagents

VC and porcine bile salt (bile acid content ≥60%) were bought from Shanghai Yuanye Biotechnology (China). VE and ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid disodium salt dihydrate (EDTA) were bought from Beijing Suolaibao Technology (China). Porcine pepsin (BR grade, 3000 U/g) and dimethyl sulfoxide were bought from Shanghai Macklin Biotechnology (China). Porcine lipase (BR grade, 30,000 U/g) was bought from Beijing Wokai Biotechnology (China). Porcine trypsin (BR grade, 4000 U/g) was bought from Tianjin Xiensi Biochemical Technology (China). Common chemical reagents were bought from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China). Curcumin was bought from Sigma Aldrich (Shanghai, China). Fish oil (DHA + EPA ≥ 70%) was bought from Xi’an Qianyecao (Shaanxi Province, China). The common chemical reagents were bought from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent (Shanghai, China).

Silver carp scale gelatin extraction

Silver carp skins with scales (Wuhan Baishazhou Agricultural and Sideline Products Market, Hubei Province, China) were scaped and cleaned to obtain scales. Then, the scales were vacuum-freeze dried and stored at −18 °C. The freeze-dried scales were soaked in ultrapure water for 30 min and then 30 g of the drained wet scales were treated with 300 mL of NaOH solution (0.1 mol/L) for 60 min with a magnetic speed of 200 rpm to remove oils. The wet scales were cleaned with water and treated with 300 mL of EDTA (0.2 mol/L) for 120 min with a magnetic speed of 200 rpm to remove minerals. The wet scales were cleaned with water and treated with 90 mL of ultrapure water at pH 7.0 at 55 °C for 3 h with an oscillating speed of 120 rpm. The wet scales were treated with water at 65 °C for 3 h and then 75 °C for 3 h. The obtained solutions were filtered, mixed, and freeze-dried to obtain dried HWSCG10.

Emulsion preparation

HWSCG was treated with water at 45 °C for 30 min with a magnetic speed of 120 rpm and then the solution pH was adjusted to 7.0. VC was added to the obtained HWSCG solution. Curcumin/fish oil (1:1000, g/mL) mixture was magnetically stirred for 12 h and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,614 × g. VE was added to the obtained fish oil supernatant. Then, curcumin/fish oil (with or without VE) was added to the gelatin solution (with or without VC) at a volume ratio of 1:113. The final VC, VE, or VC + VE (1:1) concentrations were 10 mg/mL of the emulsions. After homogenization for 90 s with a speed of 11,500 rpm30, the obtained emulsions were incubated at room temperature (RT, 20–22 °C) or 4 °C to check the storage stability.

Optical observation

The emulsion droplets were observed using an upright optical microscope (ML8000, Shanghai Minz, China) with a 40× objective. From three parallel experiments, the optical images were randomly selected and all the droplet sizes were measured13. The obtained 400–600 values for each sample were fitted with multiple Gaussian peaks to analyze the possible droplet size distribution. The emulsion appearance was photographed using a digital camera. The CI values (%) of the emulsions were calculated as follows:

Lipid oxidation

LOOH concentrations of the emulsions were measured to evaluate the lipid oxidation13. Briefly, 1 mL of the emulsion and 7.5 mL of chloroform/methanol (2:1, V/V) were Vortexed together for 1 min. The mixture was centrifuged for 5 min with a speed of 179 × g and then 0.2 mL of the chloroform/methanol extract was mixed with 2.8 mL of the methanol/1-butanol (2:1, V/V). After that, 15 μL of NH4SCN solution (3.94 mol/L) and 15 μL of ferrous iron solution (obtained with 0.132 mol/L BaCl2 and 0.144 mol/L FeSO4) were added into the mixture and Vortexed for 10 s. The mixture was stewed for 20 min in the dark and the sample absorbance was measured with a Persee Model T6 UV-visible spectrophotometer (Beijing, China) at 510 nm. The cumene hydroperoxide solutions with different concentrations were used to construct a linear absorbance-concentration equation (R2 = 0.9916) for the calculation of the LOOH concentrations (mmol/kg oil) in the emulsions.

Curcumin contents and retention

The emulsion (0.3 mL) was Vortexed with dimethyl sulfoxide (5.7 mL) and 1 mL of hexane was added. After centrifugating for 15 min at 179 × g, the lower layer with curcumin was collected. The absorbance of the collected layer was measured by a UV-visible spectrophotometer at 433 nm. The dimethyl sulfoxide with different curcumin contents was used to construct a linear absorbance-concentration equation (R2 = 0.9994) for the calculation of the curcumin contents (μg/mL) in the emulsions. The curcumin retention (%) was calculated as follows26:

In vitro digestion process of the emulsions

Three types of digestion fluids were prepared to analyze the in vitro digestion behaviors of the emulsions31. SSF: 0.06 mmol/L (NH4)2CO3, 0.15 mmol/L MgCl2, 13.6 mmol/L NaCl, 3.7 mmol/L KH2PO4, 15.1 mmol/L KCl, 1.1 mmol/L HCl, and 1.5 mmol/L CaCl2. SGF: 0.5 mmol/L (NH4)2CO3, 0.12 mmol/L MgCl2, 72.2 mmol/L NaCl, 0.9 mmol/L KH2PO4, 6.9 mmol/L KCl, 15.6 mmol/L HCl, 0.15 mmol/L CaCl2, 60 U/mL porcine lipase, and 2000 U/mL porcine pepsin. SIF: 0.33 mmol/L MgCl2, 123.4 mmol/L NaCl, 0.8 mmol/L KH2PO4, 6.8 mmol/L KCl, 8.4 mmol/L HCl, 0.6 mmol/L CaCl2, 2000 U/mL porcine lipase, 100 U/mL porcine trypsin, and 30 mg/mL bile salts. In the preparation process of these fluids, CaCl2, enzymes, and bile salts were added before the digestion research.

The emulsion (0.5 mL) was diluted with ultrapure water (4.5 mL) and mixed with 5 mL of preheated (37 °C) SSF. The mixture pH was adjusted to 7.0 and vibrated (180 rpm) at 37 °C for 2 min (salivary digestion phase). Subsequently, 10 mL of preheated (37 °C) SGF was added to the above mixture. The mixture was adjusted to 3.0 and vibrated (180 rpm) at 37 °C for 120 min (gastric digestion phase). The mixture pH was examined every 10 min (pH was 3.00 ± 0.05). Subsequently, 20 mL of preheated (37 °C) SIF 20 mL was added to the above SGF-emulsion mixture. The mixture pH was adjusted to 7.0 and vibrated (180 rpm) at 37 °C for 120 min (small intestinal digestion phase). During the digestion process, the emulsion droplets were photographed using the ML8000 optical microscope.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

CLSM was used to observe the emulsion droplets32. Briefly, Nile red (1 mg/mL) and Nile blue (10 mg/mL) mixture were made by dissolving them in 1,2-propanediol solution (2% water). Then, 40 μL of dye was mixed with 1 mL crude digested sample and incubated for 4 min in the dark. Subsequently, 5 μL of the liquid sample was photographed by CLSM (TCS SP8, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) with a 552-nm laser to excite Nile red and a 633-nm laser to excite Nile blue.

FFA release of the emulsions in the digestion process

In the small intestinal digestion phase, the mixture pH was measured every 20 min and maintained by adding 0.5 mol/L NaOH. The released percentage of FFAs was calculated as follows33:

Transformation, bioaccessibility, and bioaccessibility index of curcumin

The raw digestion liquids after the SIF phase were cooled in ice water and were centrifuged at 4 °C for 60 min with a speed of 10,614 × g. Samples of the whole original digestive fluid and the transparent curcumin-loaded interlayer were collected to measure the curcumin contents. The transformation, bioaccessibility, and bioaccessibility index of curcumin could be calculated as follows34,35:

Statistical analysis

Three parallel experiments were done for each data. Statistical comparison was done using the one-way ANOVA method with Duncan analysis (p < 0.05).

Responses