Flash synthesis of high-performance and color-tunable copper(I)-based cluster scintillators for efficient dynamic X-ray imaging

Results

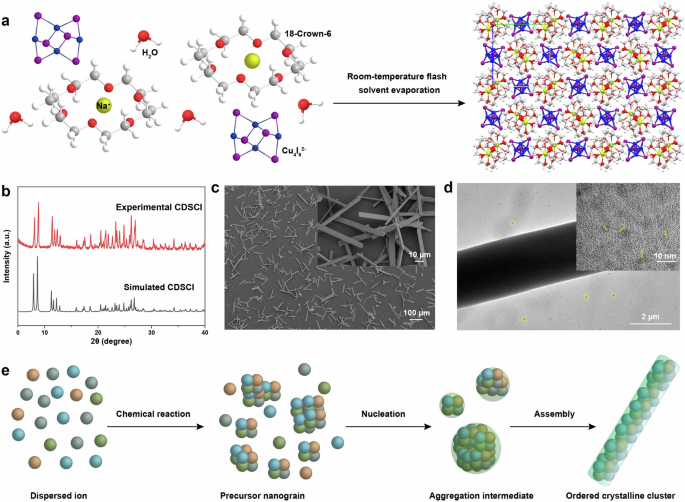

Our approach draws inspiration from the rapid assembly of inorganic cores and organic ligands into crystalline structures within DCM during its evaporation at room temperature (Fig. 1a). In our synthesis, a DCM mixture (10 mL) containing CuI, NaI, and 18-crown-6 was initially prepared at room temperature under vigorous stirring. Subsequently, centrifugation was employed to remove non-soluble substances in the reaction mixture. The resulting solution was placed in a Petri dish, leading to the formation of a yellow-green flocculent precipitate during the evaporation of DCM (Supplementary Fig. 1). X-ray diffraction studies revealed robust diffraction patterns, indicating the formation of crystalline structures. The measured X-ray diffraction profile closely matched the simulated one, confirming the formation of (C12H24O6)2Na2(H2O)3Cu4I6 (CDSCI) (Fig. 1b). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) further illustrated that the as-prepared CDSCI exhibits a rod-shaped morphology with excellent dispersibility (Fig. 1c). Detailed observations unveiled rods with a rectangular cross-section measuring 4.5 μm and an average length of 62.4 μm (Supplementary Fig. 2). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) exhibited the aggregation of nanoparticles and the weak lattice fringes, which can attribute to the passivation of the organic component (Fig. 1d).

a Schematic representation of the flash synthesis process for CDSCI scintillators. The inclusion of 18-crown-6 enables coordination with alkali metal cation (Na+), facilitating the formation of Cu4I62- anion clusters, crucial for CDSCI production during the solvent evaporation of DCM. b Comparison between measured and simulated X-ray diffraction profiles of the as-prepared CDSCI scintillator. c SEM and d TEM images displaying different magnifications of the CDSCI scintillators. e Evolution mechanism of particle assembly driven by flash synthesis in rod-shaped CDSCI scintillators.

In a subsequent set of experiments, we delved into the role of 18-crown-6 in the synthesis of CDSCI. Experiments were designed both with and without 18-crown-6 under identical conditions. Notably, the reaction system lacking 18-crown-6 exhibited a visible precipitate of raw materials, whereas the solution containing 18-crown-6 underwent an immediate color change from colorless to yellow-green. Control experiments underscored that, in the absence of 18-crown-6, the formation of CDSCI was impeded, as indicated by the absence of products after solvent evaporation (Supplementary Fig. 3). Crucially, our observations held true even when extending the experiment to a large-scale. This phenomenon can be rationalized by the inherent difficulty of CuI and NaI to dissolve in DCM. The presence of crown ethers facilitates their coordination with Na+ to form a positively charged complex, thereby enhancing the solubility of NaI and enabling the subsequent formation of Cu4I62- anions23,24. The two Na+-coordinated crown ethers then interconnect with each other, aided by two water molecules, fostering the creation of secondary building blocks that effectively segregate Cu4I62- anions within the CDSCI crystals (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 4).

According to related results, we assume the possible mechanism of rod-shaped CDSCI scintillators (Fig. 1e). The formation of the rod-shaped morphology in CDSCI crystals is attributed to the rapid evaporation of DCM. During synthesis, the swift evaporation of DCM results in a supersaturated solution of Na+-coordinated crown ethers and Cu4I62- anions, leading to the rapid generation of CDSCI nuclei. These nuclei quickly coalesce, forming large-sized domains. As DCM evaporates, a portion of the domain is exposed to air, while the other part serves as a seed, enabling the epitaxial growth of CDSCI crystals with a rod-shaped morphology. In contrast, conducting the synthesis in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) resulted in products with irregular morphology. The strong solubility of DMF allowed raw materials to persist in an unreacted state (Supplementary Fig. 5). This is attributed to the fact that the CDSCI crystal morphology synthesized in DMF is governed by thermodynamic factors. Furthermore, CDSCI crystal growth in DMF is random, lacking the driving force for oriented growth. Importantly, our strategy extends beyond CDSCI, enabling the synthesis of other family members, such as C12H24O6NaCuCl2 (CSCCl), (C12H24O6)2Na2(H2O)2CuCl2 (CDSCl), and (C12H24O6)2Na2(H2O)3Cu4Br6 (CDSCBr). The successful preparation of these Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators has been validated through X-ray diffraction measurements (Supplementary Fig. 6). Due to the facile oxidizability of CuCl and CuBr, the addition of an appropriate amount of H3PO2 as a reducing agent is necessary to inhibit oxidation during preparation. The presence of acidity and moisture seems to disrupt the orderly nucleation process and the uniformity of resultant crystals.

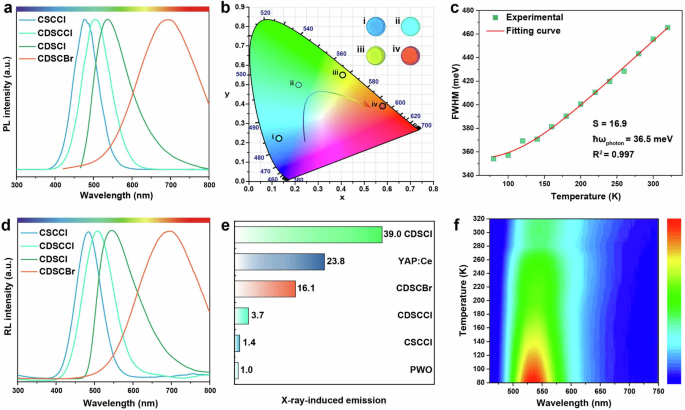

Upon UV excitation at 365 nm, the micro-sized rods of CDSCI exhibited emission centered at 536 nm. The notable advantage of utilizing Cu(I)-based cluster structures as scintillators lies in their emission bands, which exhibit a strong dependence on their compositions. For instance, under UV excitation, CSCCl, CDSCCl, and CDSCBr displayed emission bands at 438, 484, and 695 nm, respectively (Fig. 2a). While no clear trend emerged regarding the impact of halide type on the photoluminescence (PL) emission wavelength due to differing crystalline structures, the CIE coordinates and corresponding luminescence photographs of these Cu(I)-based cluster crystals illustrated a vibrant shift in emission color from blue to green and red, covering the entire visible spectral region (Fig. 2b). The Cu(I)-based cluster structures, including CDSCI and CDSCCl, exhibited photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) of nearly 100%, emphasizing their significant potential as X-ray scintillators due to their exceptional efficiency in converting absorption energy into visible photons (Supplementary Fig. 7). Furthermore, the lifetimes of the corresponding luminescence were measured at 2.0, 30, 21, and 23 μs, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 8). These collective findings strongly indicate the phosphorescent nature of these Cu(I)-based cluster crystals.

a PL profiles of the Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators under excitation at optimized wavelengths. b A CIE chromaticity coordinate diagram and corresponding photographs showcasing the as-prepared Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators under the excitation conditions. c Integrated PL intensity variation with temperature ranging from 80 to 320 K. d RL spectra observed under X-ray irradiation (operational conditions for X-ray source: 50 kV, 80 μA). e Comparative analysis of RL intensities between the Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators and commercially available scintillators YAP:Ce and PWO. Note that all measurements were subjected to X-ray irradiation at the same dosage. f Temperature-dependent RL spectra of the CDSCI scintillators from 80 to 320 K under X-ray irradiation (operational conditions for X-ray source: 50 kV, 80 μA).

The temperature-dependent photoluminescence spectra of the CDSCI scintillator revealed a decrease in emission intensity and broadening of the emission as the temperature increased (Supplementary Fig. 9 and Supplementary Table 1). This observation stems from the reduced crystal field intensity and the heightened electron-phonon coupling effect associated with increasing temperatures25,26,27. Furthermore, fitting the temperature-dependent full width at half maximum (FWHM) as a function of temperature (Fig. 2c) enables a comprehensive understanding of the luminescence mechanism (Eq. 1)27,28.

where S is denoted as Huang-Rhys factor, ℏωphoton represents the phonon frequency, and kB stands for the Boltzmann constant. Our findings reveal S and ℏωphoton values of 16.9 and 36.5 meV, respectively. Notably, these values surpass those of traditional luminescent materials like CdSe and CsPbBr3, indicating robust electron-phonon coupling and the favorable formation of self-trapped excitons (STEs). This ease of STE formation contributes to the achievement of robust STE emission and high PLQYs due to a large Stokes shift and broad-spectrum emission29,30,31. Furthermore, the photoluminescence spectrum width of CDSCI spans over 300 nm, confirming that the photoluminescence emission stems from self-trapped excitons32.

Upon exposure to X-ray irradiation, the Cu(I)-based cluster structures, namely CSCCl, CDSCCl, CDSCI, and CDSCBr, exhibited emission profiles closely resembling those observed under UV excitation (Fig. 2d). This similarity strongly suggests that the emissions originate from identical luminescent centers, even though the excitations were conducted through distinct channels. In particular, when subjected to X-rays, heavy elements such as Cu and I within the inorganic core displayed robust absorption of high-energy photons, leading to the generation of a significant number of energetic primary electrons and holes. This cascade of events initiates the production of secondary electrons through a combination of photoelectric absorption, Compton scattering, and pair formation. As these high-energy secondary electrons traverse the host lattice, they dissipate energy through interactions with the lattice and other electrons, resulting in the creation of numerous low-energy electrons and holes33,34. Subsequently, these carriers undergo rapid thermalization, giving rise to the formation of STEs. Ultimately, these excitons undergo transformation into visible scintillation photons through radiative recombination of the in situ generated STEs (Supplementary Fig. 10)35. These findings underscore the facile manipulation of radioluminescence (RL) color output by strategically designing luminescent centers using various halides in the synthesis process.

We systematically compared the scintillation performance of our synthesized Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators with commercially available counterparts. The results revealed a remarkable superiority in the RL of the CDSCI film compared to single crystals of YAlO3:Ce (YAP:Ce) and PWO4 (PWO), both of the same size and under identical dose rates (Fig. 2e). Specifically, the RL of the CDSCI film surpassed those of YAP:Ce and PWO by approximately 1.6 and 39.0 times, respectively. This heightened scintillation performance of CDSCI arises from a synergistic interplay of its exceptional X-ray absorption capability and efficient conversion of excitons into low-energy scintillation photons. Notably, despite CDSCI and CDSCBr exhibiting similar PLQYs, the RL intensity of CDSCI surpasses that of CDSCBr by approximately 2.5-fold. This discrepancy is largely attributed to the relatively weak X-ray absorption capability of CDSCBr. Furthermore, the temperature-dependent RL spectra demonstrated a consistent trend with the temperature-dependent PL spectra (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Fig. 11). Supplementary Table 1 exhibits the detailed values of FWHM in different temperatures. We attribute this observation to robust electron-phonon coupling induced by transient lattice distortion, rather than originating from permanent lattice defects under X-ray excitation36

In the performance comparison of the as-prepared copper(I)-based scintillators, we found that the copper-iodine cluster exhibited excellent scintillation performance. Structural analysis (Supplementary Fig. 12) revealed that although CDSCI and CDSCBr have similar structures, their X-ray absorption capacities differ significantly due to the differences in their anionic components, Cu4I62- and Cu4Br62-. Furthermore, unlike CSCCl, the presence of 18-Crown-6 combined with Na+ in CDSCCl acts as a large macrocyclic ligand. This combination significantly increases the distance between luminescent anion clusters, effectively inhibiting non-radiative recombination and enhancing luminescence performance37,38.

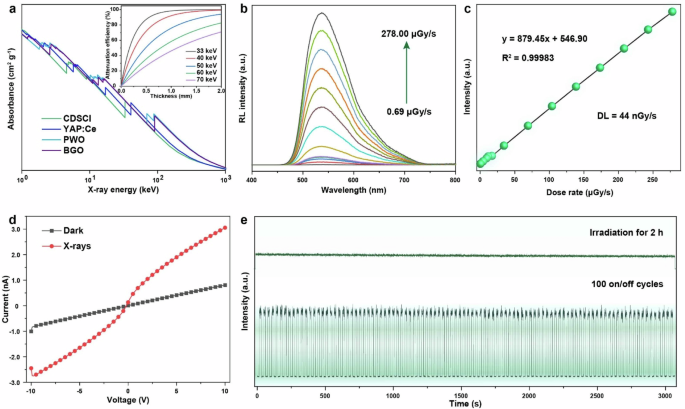

We conducted a quantitative assessment of the absorption coefficient of the as-prepared CDSCI in comparison to commercially available scintillators, namely YAP:Ce, PWO, and BGO, leveraging the XCOM-NIST database for reference (Fig. 3a). Surprisingly, our findings indicated that although CDSCI exhibits a weaker absorption coefficient than BGO, it outperforms BGO in scintillation performance, emphasizing the pivotal role of PLQY in efficiently converting excitons into low-energy scintillation photons (Eq. 2)8,39.

where E represents the energy of incident X-rays, β is a constant parameter, Eg is the bandgap energy, S denotes the host-to-emission center energy migration efficiency, and Q is the quantum efficiency, equating to the PLQY. The inset graph illustrates the effective X-ray attenuation efficiency relative to energy, highlighting that a 1.5 mm thick film of CDSCI microrods can effectively attenuate the majority of incident X-rays. In the dose rate range of 0.69 to 278 μGy s−1, the RL of CDSCI microrods exhibited a linear response to the X-ray dose rate (Fig. 3b), excluding the contribution of defect recombination in scintillation emission generation22.

a X-ray absorption coefficients of CDSCI, YAP:Ce, PWO, and BGO as a function of photon energy. The inset illustrates the attenuation efficiency of CDSCI scintillators in relation to thickness under different irradiation conditions. b X-ray-induced RL spectra of CDSCI scintillators at varying dose rates ranging from 0.69 to 278 μGy s−1. c RL intensity presented as a linear function of the dose rate. d Current–voltage curves of CDSCI film observed both with and without X-ray irradiation. e Evaluation of X-ray resistance in CDSCI scintillators, demonstrated through continuous X-ray irradiation for 2 h (top panel) and on-off repeated irradiation for 100 cycles at a dose rate of 2.85 mGy s−1 (bottom panel).

Additionally, the detection limit (DL) of CDSCI was determined to be 44 nGy s−1 using a three-time signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) method, surpassing the requirements for standard medical diagnosis by approximately 125 times (Fig. 3c). Current–voltage (I–V) curves were recorded both in a dark environment and under X-ray irradiation (Fig. 3d), revealing a notable increase in current upon exposure to X-rays. These outcomes underscore the semiconducting nature of the CDSCI scintillator, enabling the generation of additional charge carriers within the matrix when heavy metal atoms absorb high-energy X-ray photons40. Furthermore, the radiation stability of the as-prepared scintillator was evaluated by long-term high-dose radiation irradiation for 2 h and switching cycles with an interval of 15 s, respectively. The CDSCI scintillator demonstrated remarkable robustness against X-rays, as evidenced by the absence of scintillation degradation during continuous X-ray irradiation or repeated X-ray exposure at a dose rate of 2.85 mGy s−1 (Fig. 3e).

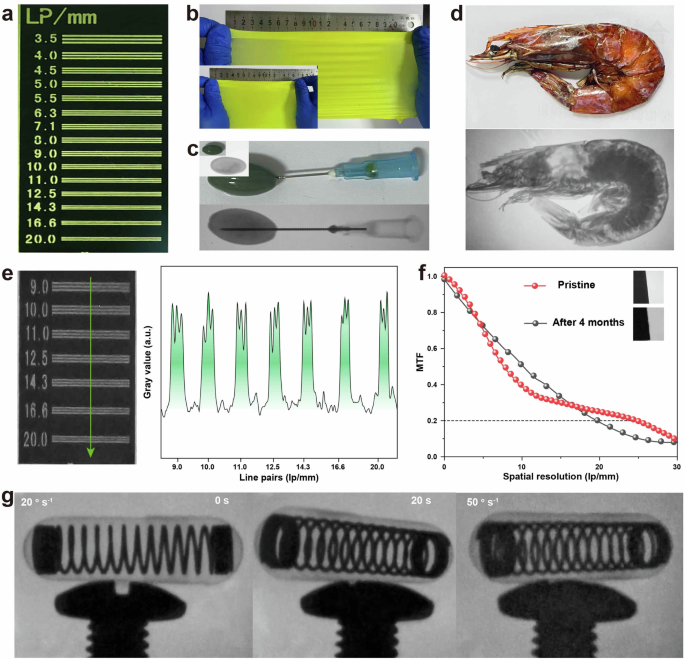

The outstanding scintillation performance of CDSCI microrods enables the application of X-ray imaging studies when incorporated into a doped polymer matrix to form a scintillation screen. A flexible scintillation screen was created by blending NaI, CuI, 18-crown-6, and a thermoplastic polyurethane solution in DCM. Subsequent solvent evaporation yielded a homogeneous yellow-green polymer film. The flexible film exhibited minimal light scattering and high light transmittance, demonstrated by the clear observation of details on a standard line-pair card through the scintillator film (Fig. 4a). The CDSCI-doped thermoplastic polyurethane demonstrated considerable stretchability, extending to at least 125% under external force (Fig. 4b). In X-ray imaging, the flexible CDSCI-doped scintillation film translated intensity variations of penetrating X-rays into visible emissions, recorded by a digital camera. Clear X-ray photographs were obtained, revealing details within a capsule containing oily substances with an inserted needle and shrimp with varying tissue densities (Fig. 4c, d). The film displayed the internal structure and information differences of objects, showcasing potential applications in nondestructive inspection and biological tissue diagnosis. The CDSCI-doped scintillation film achieved a spatial resolution of 20 lp/mm at a dose rate of 2.9 mGy s−1 (Fig. 4e). Utilizing the slanted-edge method to evaluate the theoretical spatial resolution, considering a modulation transfer function (MTF) value of 0.2 representing the distinguished boundary, the spatial resolution was estimated to be 24.8 lp/mm (Fig. 4f). Given the short luminescence lifetime of CDSCI, we explored the feasibility of CDSCI scintillation films for dynamic real-time X-ray imaging (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Video). Our results illustrated X-ray image details of a rotating capsule with a built-in spring at varying speeds. Importantly, up to a rotating speed of 50 degrees per second, no ghosting effects were observed in the X-ray image, underscoring the qualification of CDSCI scintillation films as a promising candidate for real-time X-ray imaging.

a Visualization of the standard line-pair card through the flexible CDSCI-doped scintillation film. b Photographic presentation of flexible CDSCI-doped scintillation films at various stretch lengths. c, d X-ray images and corresponding photographs depicting a capsule containing oily substances with an inserted needle and shrimps exhibiting different tissue densities. e X-ray photographs and the grayscale function of a standard line-pair card. f Measurement of MTF using the slanted-edge method. g Real-time X-ray images capturing the rotation of a capsule equipped with a built-in spring.

Discussion

Our study successfully showcases the facile achievement of color-tunable scintillation emissions in Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators. This breakthrough is attained through the swift nucleation driven by crown ethers at room temperature, leveraging the modulation of halogen components. Our findings reveal that the resulting scintillation emissions encompass the entire visible spectral region. The broad-spectrum emission of CDSCI is rooted in STEs, as comprehensively characterized through a combination of experimental and theoretical approaches. Significantly, our scintillator demonstrates an impressively low detection limit of 44 nGy s−1, surpassing the standard dosage by about 125 times. This exceptional sensitivity positions our material for practical applications in flexible scintillation films, particularly for high-resolution and low-dose X-ray radiography, as well as dynamic real-time X-ray imaging. The versatility of our strategy, considering the diverse components involved, establishes a pragmatic route for exploring low-cost, high-performance, and color-tunable Cu(I)-based hybrid materials. This not only expands the scope of scintillator applications but also pioneers innovative solutions in radiation detection and imaging technologies.

Methods

Materials

NaCl (99.9%) was purchased from Anhui Zesheng Technology Co., Ltd. Cuprous iodide (CuI, 99%) was obtained by Alfa Aesar. Sodium iodide (NaI, 99.99%), sodium bromide (NaBr, 99.99%), 18-crown-6 (99%), cuprous bromide (CuBr, 99.9%), cuprous chloride (CuCl, 99.95%), hypophosphorous acid (H3PO2, AR, 50 wt.% in H2O) and N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF, 99.5%) were provided by Shanghai Aladdin Biomedical Technology Co., Ltd. Thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU, 60HA) was acquired from Taiwan Kin Join Co., Ltd. Dichloromethane (DCM, 99.5%) was procured from Shanghai Titan Scientific Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of Cu(I)-based cluster scintillators

In a typical experiment, a mixture comprising CuI, NaI, and 18-crown-6 in equimolar ratios was dissolved in 10 mL of DCM. The solution was vigorously stirred, and after a specified duration of standing, the supernatant was collected and uniformly dispersed onto a Petri dish. Following a brief period of solvent evaporation, the resulting CDSCI products were promptly gathered. The synthesis procedure for CDSCBr and CDSCCl mirrored that of CNI, with the substitution of sodium and copper(I) salts, and the addition of a small quantity of H3PO2 to enhance oxidation resistance. Notably, the preparation of CDSCCl incorporated an additional 2-fold increase in the amount of 18-crown-6.

Preparation of flexible CDSCI-doped scintillation films

In brief, the fabrication of flexible CDSCI-doped scintillation films commenced with the preparation of a pre-established thermoplastic polyurethane (TPU) solution. A predetermined quantity of TPU was accurately weighed and dissolved in N,N-dimethylformamide. Achieving a 20% concentration, the solution underwent ultrasonic dispersion and heating at 80 °C under vigorous stirring. Subsequently, 5 mL of the previously prepared CDSCI supernatant was introduced into the 10 mL TPU solution. Ensuring homogeneity through uniform mixing and ultrasonic treatment, the resulting solution was transferred to a polytetrafluoroethylene mold and cured at 40 °C for 3 h. Following this, the mold was removed from the oven and transitioned to a cool environment, yielding a flexible scintillation film.

Characterization

Powder X-ray diffraction was measured by a Bruker D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) was conducted on Bruker D8 VENTURE double micro-focal spot single-crystal diffractometer equipped with a PHOTON III CPAD photon counting detector. Scanning electron microscopy was provided by using a Zeiss Gemini 300 microscope at an acceleration voltage of 3 kV. Transmission electron microscopy was performed on a Hitachi HT 7800 operating at an acceleration voltage of 100 kV. PL, RL, and luminescence decay were obtained on FSL-1000 (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd.) equipped with an external miniature X-ray source (AMPEK, Inc.). PLQY was measured by FSL-1000 (Edinburgh Instruments Ltd.) equipped with an integrated sphere. X-ray imaging was performed by a homemade setup with the use of an external miniature X-ray tube as excitation, a CDSCI scintillation film, a prism, and a digital camera, respectively.

Responses