Focal therapy using high-intensity focused ultrasound with intraoperative prostate compression for patients with localized prostate cancer: a multi-center prospective study with 7 year experience

Introduction

Five-year treatment-free and overall survival outcomes of active surveillance in 672 patients with localized invisible and visible prostate cancer (PC) on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels of 20 ng/mL, and Gleason scores of 3 + 3 or 3 + 4, were 83.4% and 72.3%, and 62.8% and 33.8%, respectively [1]. On the other hands, radical treatments [2] remain concerns such as the deterioration of urinary [3] and sexual function [4] after radical prostatectomy, as well as radiation-induced hemorrhagic cystitis [5] and severe rectal bleeding [6] after radiation therapy. Focal therapy has been is studied to evaluate whether a credible treatment strategy to provide both cancer control and functional preservation.

High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) uses ultrasound waves generated by a spherical transducer to deliver ultrasonic energy to the target area [7], allowing for a distinct margin between the treated and adjacent normal tissue [8]. The characteristics of HIFU is attractive as one of modalities for focal therapy. However, clinically significant PC (CSPC) detection rates of treated area with biopsies performed at different postoperative timings and with different methods to assess treatment efficacy were in the range of 8.2% [9], 17.2% [10], and 40% [11] after focal therapy with HIFU. This variation is considered due to the use of non-uniform energy output settings in focal therapy.

The hyperechoic changes on B-mode of TRUS images indicate effective treatment during the PC treatment with HIFU [12, 13]. However, the diffuse appearance of hyperechoic changes are less likely to appear in the treated area due to the cooling effect caused by blood flow and long path of HIFU propagation. Compression of the prostate reduces the vascular flows in intra-prostatic plexus, and helps minimize the heat sink effect. Further, the compressed tissue reduces the HIFU propagation path resulting in higher intensity at the focal site to promote cavitation [14]. By the compression of the prostate, we experienced the diffuse appearance of hyperechoic changes during the HIFU procedure in the previous study [15]. In the present study, focal therapy using HIFU with intraoperative prostate compression was performed for patients with localized PC.

Patients and methods

Patients treated from June 2016 to July 2021 at the Tokai University affiliated hospitals, and who had serum PSA levels of ≤20 ng/ml, and presented with evidence of CSPC on MRI-TRUS elastic fusion image-guided transperineal target biopsy and 12-core transperineal systematic biopsy (Supplementary Fig. 1), were eligible for this study. The inclusion criteria included life expectancy of > 10 years, no evidence of metastasis on contrast-enhanced CT and bone scintigraphy, focally localized CSPC within the left or right half, or upper or lower half of the prostate, Gleason score was limited to 4 + 4 or below, with MRI-visible lesions in 4 + 4 cases restricted to 15 mm or less, MRI showed no extracapsular or seminal vesicle invasion, no severe anal strictures, and no history of previous treatment for PC. The patients were informed that the study treatment was optional, offered in addition to the standard treatment, and were asked to provide informed consent prior to study enrollment. All patients were followed up for at least 24 months. The study protocol adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki. This prospective study was approved by the Jikei University Certified Review Board (JKI18-017) and was registered to Japan Registry of Clinical Trials (jRCTs032180303).

Multimetric MRI and image analysis

MRI scanning was performed using a 1.5 (Signa HDx®; GE Healthcare, Amersham Place, UK) or 3.0-Tesla (Ingenia, Philips Healthcare, Best, the Netherlands) MRI scanner. T1-weighted axial fast spin-echo images were obtained before a contrast injection. All MRI examinations were performed using the same protocol and included non-enhanced T2-weighted imaging in the axial and sagittal planes, diffusion-weighted imaging, apparent diffusion coefficient maps, and dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE) MRI, using a fat-saturated T1-weighted fast-field echo sequence in the axial plane. All mpMRI images were reviewed by two experienced radiologists who were blinded to the patients’ clinical information. CSPC suspected lesions were evaluated from category 3 to 5 with PI-RADS version 2.0 [16].

Biopsy protocol

The biopsy process started with MRI-TRUS fusion image-guided target biopsies with BioJet (D&K Technologies GmbH, Barum, Germany), after which 12-core systematic biopsies (Supplementary Fig. 1) were performed transperineally. An 18-G automatic biopsy gun with a 22-mm specimen size (PRIMECUT®, TSK Laboratory, Tochigi, Japan) was used to obtain the biopsy cores.

Pathological analysis

All biopsies were examined by two senior pathologists who reviewed each other’s results. In the present study, cases of MRI-visible CSPC were defined as ‘mpMRI-visible’ lesions with a Gleason score of 3 + 4, or a score of 6 with a maximum cancer core length of ≥4 mm, using the targeted biopsy.

Location of CSPC

Locations of mpMRI-visible CSPC were recorded by the partitioned regions of the prostate (Supplementary Fig. 2), which were created with the contours of the transition zone (TZ) and peripheral zone (PZ), and the location of urethra.

Region targeted focal therapy with histotripsy using HIFU

The treatment range involved the partitioned regions of the prostate on TRUS image on the HIFU workstation of Sonablate®500 (Sonablate Corp., Charlotte, NC, USA), based on the recorded partitioned regions of each mpMRI-visible CSPC and a margin of at least 5 mm. The features of the Sonablate®500 have been described previously [15]. The user can adjust the power level throughout the procedure to ensure adequate treatment of the target area. The energy output was adjusted intra-operatively from 20 W to 48 W for a diffuse appearance of hyperechoic changes across the entire therapeutic area on TRUS (Supplementary Fig. 3) in all patients. As technical ingenuity for sufficient energy irradiation to the treatment area, transrectal compression was used [17], which involves introducing additional 80-160 mL of water into the transducer balloon to apply pressure on the prostate, which helps reduce intra-procedural prostatic swelling [18] and decreases the target displacement [17], increasing treatment accuracy.

Evaluation of oncological outcomes

The PSA values were measured every 3 months for 24 months and every 6 months for 24 months thereafter. DCE MRI were obtained to evaluate the blood flow in the treated area at 1 month. At 6 months, MRI-TRUS elastic fusion image-guided transperineal target biopsies for the treated areas and any cancer suspicious regions with PI-RADS category 3, 4, and 5 if existed, and 12-cores systematic biopsies were performed for initial continuous 100 patients to evaluate the treatment effect. Biochemical failure was defined by the Phoenix ASTRO definition [19]. For the patients with biochemical failure, the MRI-TRUS fusion image-guided target biopsy was recommended in cases of CSPC-suspicious lesion classified as PI-RADS category 3, 4, and 5; thereafter, the 12-core systematic biopsies were performed. Pathological failure was defined as having CSPC in the biopsy at the time of biochemical failure. The patients received no treatment without pathological failure.

Longitudinal analysis of functional outcomes

We used the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), IPSS Quality of Life (QOL), Overactive Bladder Symptom Score (OABSS), and uroflowmetry and the scores of urinary subscales of Expanded Prostate Cancer Index Composite (EPIC) to assess urinary function. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF)-5 scores and EPIC sexual function scores were used to assess erectile function. The EPIC and Medical Outcomes Study Questionnaire Short Form 36 (SF36) were used to assess health-related QOL. The scores were evaluated before treatment (baseline) and at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, and 24 months after treatment. Severe erectile function was defined as an IIEF-5 score of ≤7 points. Complications were evaluated during the follow-up after treatment with Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS® Statistics version 26 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The differences in oncological outcomes were compared among the risk groups using one-way analysis of variance. The differences in biochemical failure rates were analyzed using the Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the T-stage, Gleason scores, and D’Amico risk classification. Multivariable logistic regression analyses with stepwise variable selection were performed to evaluate the predictors of CSPC in the patients’ clinical data. Binary outcomes such as CSPC detection in follow-up biopsy at 6 months after the treatment and biochemical failure were analyzed using chi-square test for categorical variables and logistic model for continuous variables. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

The patients’ (n = 240) characteristics are presented in Table 1. The median procedural time (minutes), ablation time (minutes), and total HIFU energy per case (K Joule) (range) were 44 (11–75), 22 (4.0–44), and 17,824 (3028–30,274) in the low-risk group, 44 (8–85), 22 (4.0–51), and 17,924 (5940–42,154) in intermediate-risk group, and 48 (8–102), 24 (4.0–52), 18,124 (3034–36,124) in the high-risk group, respectively. The median HIFU treatment zone (range) was 2 (1–3). The procedural (P = 0.462) and ablation (P = 0.228) times, and total HIFU energy per case (P = 0.228) were comparable among the groups. Catheterization and hospitalization times were within 24 hours after treatment for all patients.

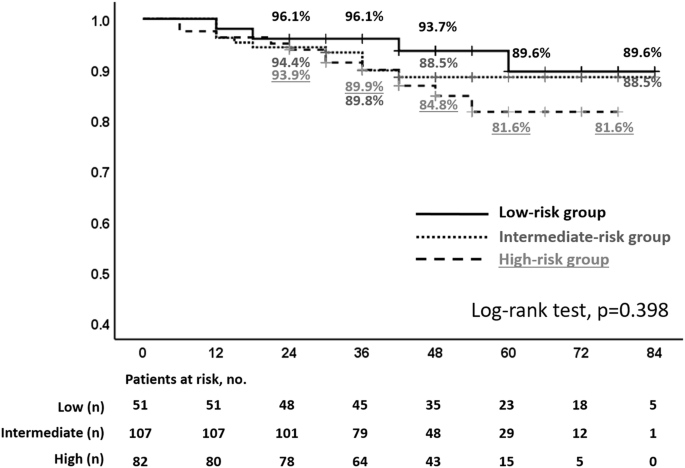

Oncological outcomes are presented in Table 2 and Fig. 1. A month post-treatment, the treated areas appeared as completely devascularized on DCE MRI. There was no evidence of any definitive change in the peri-targeted area or rectum wall on the DCE MRI at 1month. Biopsy to assess treatment efficacy at 6 months post-treatment for the initial 100 patients revealed no evidence of CSPC in the treated area. However, in nine cases, CSPC was detected in the un-treated areas more than 10 mm away from the treated area. Univariate analysis revealed a linear correlation between the highest PI-RADS category before the biopsy and CSPC (p < 0.0001). PSA density (PSAD) values at 6 months after treatment were associated with CSPC risk in a logistic regression model (p = 0.0036, odds ratio=0.1; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.95 [1.24–3.05]). The AUCs using the classification with the highest PI-RADS category and PSAD were significantly greater than non-discrimination (AUC 0.975, 95% CI 0.947–1.000; p < 0.0001). The sensitivity and specificity of combined PI-RADS category ≥3 and PSAD ≥ 0.067 ng/mL/cc were 63% and 95% for the detection of CSPC in the routine biopsy at 6 months, respectively. Among the patients with the evidence of CSPC, eight patients progressed to biochemical failure. Differences between the patients’ characteristics and biochemical failure in clinical factors and PSA kinetics were shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively. In multivariable logistic regression analysis, pre-procedural prostate volume (Supplementary Table 3), nadir value, serum PSA level, and PSA velocity after PSA nadir value (Supplementary Table 4) were the risk factors for biochemical recurrence after the treatment. Overall, 10% (n = 24) of all patients were diagnosed with pathological failure and treated with re-focal therapy (n = 9), radical intensity-modulated radiation therapy (n = 12), robot-assisted radical prostatectomy (n = 2), and intermittent hormonal therapy (n = 1) because of the need to treat other malignancies.

The rates in the D’Amico classification low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups were 89.6%, 88.5%, and 81.6% for 7 years, 89.6%, 88.5%, and 81.6% for 5 years, and 93.7%, 88.5%, and 84.8% for 4 years, respectively.

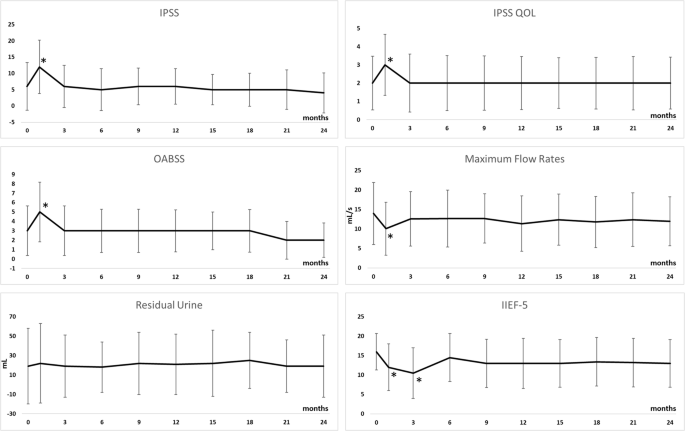

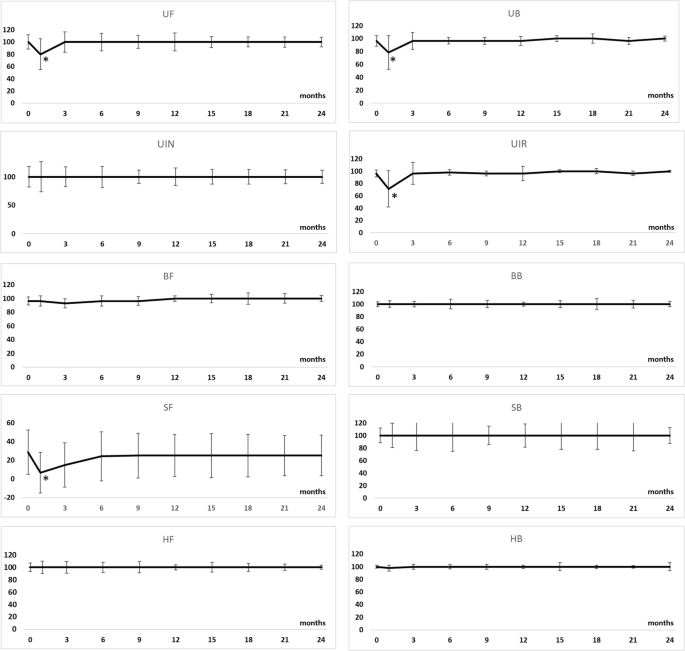

Longitudinal changes in the IPSS, IPSS QOL, OABSS, maximum urinary flow rate, residual urine, and IIEF-5 are shown in Supplementary Table 5 and Fig. 2. Longitudinal changes in the subscale scores of EPIC are shown in Supplementary Table 6 and Fig. 3. Although some urinary function related-scores were significantly impaired at 1 month after treatment compared with pretreatment values, they returned to baseline levels 3 months after treatment. Longitudinal changes in the SF36 scores are shown in Supplementary Table 7 and Supplementary Fig. 4. At 1 month after treatment, body pain, vitality, social functioning, and mental health scores were impaired relative to the pre-treatment values, but they returned to their baseline levels at 3 months post-treatment. In complications, the rates of urethral stricture (Grade 2), urinary tract infection (Grade 2), urinary incontinence (Grade 1), and recto-urethral fistula were 2.9%, 2.1%, 1.3%, and 0%, respectively. Severe erectile dysfunction was occurred in 24% of the patients with pre-procedural IIEF-5 ≥ 8.

Compared with pretreatment values, IPSS (P < 0.0001), IPSS QOL (P = 0.002), OABSS (P < 0.0001), and maximum urinary flow rate (P < 0.0001) were significantly impaired at 1 month after treatment. However, they returned to baseline levels and did not significantly differ 3 months after the treatment. IIEF-5 was significantly impaired at 3 months after treatment compared with the pretreatment value, but improved to baseline levels at 6 months after the treatment.

Although urinary function (P = 0.030), urinary bother (P = 0.003), urinary irritative/obstructive (P < 0.0001), and sexual function (P = 0.018) scores were significantly lower at 1 month after treatment than pre-treatment, they did not significantly differ at 3 months after treatment. UF urinary function, UB urinary bother, UIR urinary incontinence, UIN urinary irritative/obstructive, BF bowel function, BB bowel bother, SF sexual function, SB sexual bother, HF hormonal function, HB hormonal bother, SD standard deviation, P-value indicates comparison with pre-procedural value.

Discussion

In the present study, the energy output was increased until hyper-echoic changes became visible across the entire therapeutic area on TRUS images during the procedure through technical ingenuity by intra-procedural prostate compression [17], and indicating the effective treatment of vaporization of water tissue due to heat effect and acoustic cavitation [20]. The technical ingenuity increases treatment accuracy [17, 18] and intensity at the target area [14]. As a result, the treated areas presented some evidence of fibrosis and no cancerous lesions in routine follow-up biopsies at 6 months in initial continuous 100 patients. Compared to the previous reports that CSPC detection rates of treated area from 8.2% to 40% [9,10,11] with biopsies performed at different postoperative timings and using different methods to assess treatment efficacy, the pathological result of the follow-up biopsy in the present study was superior. The rates and types of observed complications were consistent with those previously reported [21, 22], and no case of recto-urethral fistula was observed in the present study. This evidence suggests that focal therapy using HIFU with intraoperative prostate compression would deliver suitable energy levels to treat the target CSPC, with a satisfactory safety profile.

In this study, the biopsy to assess treatment efficacy performed at 6 months in 100 patients revealed the evidence of CSPC in nine cases in areas that had not been treated. Our results suggest that routine biopsy to assess treatment efficacy may be redundant in most patients and that it should be indicated for patients depending on their PI-RADS category and PSAD. Among the 17 patients with pathological failure, 13 patients were diagnosed within 24 months after the treatment. These patients may have been cases of diagnostic failures, whereby the evidence of CSPC was not detected by either MRI scans or biopsies. In the multivariable logistic regression analysis in patients’ characteristics, prostate volume was a significant risk factor to biochemical recurrence (Supplementary Table 3). Previous study reported that there was a relatively high rate of upgraded pathology in whole-gland specimen with radical prostatectomy after focal therapy with irreversible electroporation [23]. Based on these results, patient selection and complete treatment are considered important factors for the success of focal therapy. Further, rigorous follow-up after FT with biomarker, imaging, and biopsy would be needed to avoid missing cancer progression. The biopsy protocol in this study followed the method we previously implemented, which detection of CSPC was over 90% based on the comparison with whole-mount specimens [24]. However, the number of systematic biopsies in our protocol was set at 12, regardless of the prostate volume, some cases of CSPCs may have been missed in patients with large prostates before treatment. To improve diagnostic accuracy, target and template saturation biopsy might also be necessary for the patients with large prostate.

Transient prostatic swelling just after the HIFU ablation [18] may account for the increased pressure on the urethra and difficulty in urination; it generally resolves within 2 months after treatment [25]. In the present study, the transient deterioration of urinary function was observed as deterioration of maximum flow rate and urinary irritative/obstructive, which was thought to be due to temporary prostate swelling causing compression of the urethra. However, they improved within 3 months; this duration was similar to that of the prostate swelling [26]. A previous study has shown a greater risk of urinary dysfunction with treatment in the anterior TZ portion than in the other prostate portion at 1 month after focal therapy with HIFU [27]. Meanwhile, the rate of severe ED (IIEF-5 ≤ 7) was 36% at 12 months in patients without severe ED before the treatment. In our previous report, multivariable logistic regression analysis results revealed that lower pre-procedural IIEF-5 and EPIC sexual domain scores, and treatment to the edge of PZ, proximal to the neurovascular bundle, were risk factors for severe ED [28]. Patients should be informed about these risks prior to treatment as part of the consent-giving process.

This study had some limitations. First, it was a mid-term follow-up single-arm study. Because conducting a randomized control trial is not straightforward, a prospective pair-matched study with standard treatments would be required for the evaluation of usefulness of focal therapy. Furthermore, a statistical analysis that assesses not only cancer control but also functional outcomes [29] is needed. Second, biochemical failure was evaluated with the Phoenix ASTRO definition, which was designed for use after radiotherapy. Therefore, this study used other indicators, such as pathological recurrence and radical or systematic treatment-free rates, to evaluate oncologic outcomes. Thirdly, the median prostate volume of the patients in this study was less than 30 cc. In patients with larger prostates, prostate cancer diagnosis by biopsy and post-treatment functional outcomes may differ.

Conclusions

Focal therapy using HIFU with intraoperative prostate compression would improve medium-term oncological outcomes without the risk of functional deterioration. Future studies should include a comparison group to evaluate the contribution of this approach to improving functional and oncological outcomes associated with standard treatments.

Responses