From greenery to community: exploring the mediating role of loneliness in social cohesion

Introduction

In recent years, environmental factors have gained prominence in research on societal well-being, with vegetation conditions emerging as a key area of interest due to their potential impact on subjective well-being1, particularly during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic2,3,4,5. This study aims to explore the relationship between vegetation conditions, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation, providing a deeper understanding of how green spaces promote social sustainability and strengthen community cohesion.

In the context of rapid urbanization, recent research has increasingly focused on the role of environmental conditions6, particularly vegetation, in shaping the non-monetary aspects of well-being7. A growing body of literature has documented the positive effects of green spaces on physical and psychological health8,9,10,11,12, life satisfaction13,14, and social inequalities15,16,17. The COVID-19 pandemic underscored the critical role of such spaces, which provided essential mental health relief during periods of restricted social interaction18,19,20,21,22,23. Despite this growing evidence, the broader social implications of vegetation—particularly its influence on social cohesion and societal fragmentation—remain underexplored, warranting further investigation.

Social cohesion, encompassing elements such as social trust and mutual support, plays a critical role in fostering community solidarity and maintaining societal stability. Research highlights its importance in promoting shared values, collective responsibility, and resilience within social structures, thereby reducing the risk of societal fragmentation24,25.

This study investigates loneliness as a mediating factor between vegetation conditions in living environments and perceptions of societal fragmentation. Existing research highlights loneliness as a complex phenomenon shaped by emotional and social26, and cultural dynamics27, as well as the influence of digital environments28. It also intersects with existential concerns and identity formation29,30, calling for a holistic approach that considers the diverse contexts in which loneliness arises and impacts individuals31,32,33,34,35,36, particularly in relation to environmental conditions and their societal implications. Hannah Arendt’s37 reflections on loneliness provide a broader perspective by linking it to societal anomie and alienation, underscoring its significance as more than an individual psychological issue. In this context, loneliness emerges as a critical social condition with profound implications for societal stability and cohesion.

The appointments of Ministers of Loneliness in the UK (2018) and Japan (2021) reflect growing recognition of loneliness as a pressing social issue. In response, urban greening has emerged as a promising policy solution, with the UK’s loneliness strategy explicitly emphasizing the role of urban green spaces in mitigating loneliness38. Building on the theoretical insights and the policy context, this study investigates how vegetation conditions—particularly the vegetation density and health in residential areas—affect feelings of loneliness and shape perceptions of societal fragmentation. By examining these dynamics, the study seeks to deepen understanding of the environmental factors influencing social well-being and cohesion.

To explore the relationship between environmental factors, loneliness, and societal perceptions, this study integrates district-level vegetation indices derived from remote sensing data with individual-level survey responses collected during the peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021—a period marked by heightened community stress. South Korea (hereafter Korea) provides a particularly relevant context for examining these relationships due to its unique socio-environmental dynamics. During the pandemic, strict social distancing measures and limits on gatherings were enforced, while outdoor activities in open spaces remained permitted. This policy setting highlights the potential role of green spaces in mitigating social isolation. Moreover, Korea ranks the lowest in social support among OECD member countries39, suggesting that its population experiences substantially lower levels of social support compared to individuals in most other OECD nations. This deficiency has critical implications, as it indicates a heightened vulnerability to loneliness among a significant portion of the Korean population, making the country an important case for studying how environmental conditions affect social cohesion.

Results

Loneliness and the importance of greenness

Wilson’s Biophilia Theory posits that humans have an inherent connection to nature, deeply rooted in their minds and genes, which promotes physical and mental well-being and enhances satisfaction in natural environments40. This theory is linked to the Savanna Hypothesis, which suggests that humans evolved a preference for environments resembling the savannah, where early humans lived41. This preference is not only survival-based but also contributes to psychological and physical well-being42.

Supporting the Biophilia Theory, various empirical studies have demonstrated the positive effects of natural environments on human well-being43. For instance, the Stress Recovery Theory (SRT) explains how natural environments reduce stress, a response grounded in human evolutionary history44,45. Similarly, the Attention Restoration Theory (ART) argues that natural settings restore cognitive function, helping individuals manage daily demands more effectively46,47. However, research on the relationship between green space and loneliness yields mixed results48. Some studies demonstrate a clear association between green space and reduced loneliness. For instance, Hammoud et al.49 and Villeneuve et al.50 report that contact with nature and urban greenness respectively lower the likelihood of loneliness and social isolation. Similarly, research by Astell-Burt et al.51 in Australia and Maas et al.52 in the Netherlands shows that increased urban greening and surrounding green spaces significantly alleviate loneliness, with additional findings by Van den Berg et al.53 highlighting reduced loneliness among older adults with access to allotment gardens.

On the contrary, other studies do not establish a significant relationship between green space and loneliness. For instance, Zijlema et al.54 and Soga et al.17 find no reliable association between objectively measured green space and loneliness. Similarly, Ward Thompson et al.55 identify only a minor, non-statistically significant link between the percentage of green space within an administrative area and social isolation. Lai et al.56 observe a statistically significant association between residential greenness within a 500 m buffer and social isolation, but not loneliness.

Although evidence regarding the effect of green spaces on reducing loneliness remains inconclusive, a substantial body of research suggests that various mechanisms can help alleviate loneliness. Features such as benches, trees, and gardens within green spaces like parks can evoke comforting memories and foster a sense of connection57,58. Moreover, the psychological benefits of green spaces may be experienced without direct physical immersion, such as through a pleasant view from a window59,60,61.

Furthermore, green spaces extend their social impact beyond individual benefits, playing a critical role in enhancing social connectedness. Urban parks serve as venues where neighbors and families from different generations can interact, thereby facilitating the formation and preservation of social capital62. Moreover, regular social programming within these green spaces can further consolidate community bonds by providing venues for public gatherings and events63. Astell-Burt et al.51 emphasize that urban greening may serve as an effective population-level strategy for mitigating loneliness. The implications of loneliness extend beyond individual well-being, impacting broader societal outcomes, particularly in the realm of social connectedness. Strengthening social ties, which can be fostered through the presence of green spaces, plays a crucial role in mitigating societal loneliness64.

Loneliness and fragmented society

Fromm Reichmann65 defines loneliness as an intense and overwhelming experience of isolation and disconnection from others, emphasizing that it is not merely a temporary emotional state but a profound condition with significant implications for an individual’s mental health and well-being. This perspective underscores the complexity of loneliness, recognizing it as a multifaceted and deeply personal experience that extends beyond the simple absence of social contact.

Building on this foundational understanding, Perlman and Peplau66 refines the definition of loneliness, characterizing it as a harmful experience resulting from an individual’s perception of a deficiency in their social connections, with an emphasis on the quality of these connections. Their work highlights the subjective nature of loneliness, describing it as an adverse emotional reaction based on an individual’s evaluation of their social relationships against personal criteria for fulfilling interactions.

Further advancing this framework, Barjaková et al.67 conducted a systematic review that deepens our understanding of loneliness. Their analysis shows that loneliness is more strongly associated with the quality and functionality of social networks than with their size. This suggests that loneliness results not simply from the quantity of social contact but from a complex interplay of social norms, comparisons, and the desired quality of social ties.

Loneliness is associated with a range of emotional and psychological consequences. Individuals experiencing loneliness often exhibit a strong desire for shared identity, community, and affiliation, yet these needs remain unmet in their daily lives16. They are also more likely to suffer from increased social anxiety, pessimistic expectations about future events, and fear of negative judgment by others68,69. Additionally, loneliness is linked to a tendency towards prevention-oriented rather than promotion-oriented goals70 and serves as a risk factor for depression71. Moreover, social isolation is identified as a significant risk factor for physical inactivity and cognitive decline72. Loneliness is also a strong predictor of individual well-being73 and physical health74,75. Beyond its individual impacts, loneliness can negatively affect perceptions of social cohesion at both individual and societal levels37,76.

Riesman et al.76 emphasize the paradox of feeling lonely despite being surrounded by others. In such circumstances, individuals often confront existential questions about their place in the world, leading to diminished self-worth and self-contempt. This internalized negativity can outwardly manifest as hostility towards others, promoting discriminatory attitudes and behaviors that erode social cohesion.

Hannah Arendt’s37 philosophical exploration of loneliness offers a valuable perspective on its relationship with social relationships. Unlike contemporary psychological approaches, which often focus on perceived deficiencies in social connections, Arendt37 conceptualizes loneliness as intrinsically linked to social anomie and alienation. Arendt37 suggests that loneliness engenders a profound sense of estrangement from both others and oneself, leading to a crisis of identity and meaning. Those deeply affected by loneliness may come to view society as fundamentally fragmented and untrustworthy, fostering a pervasive cynicism that erodes the trust necessary for social cohesion. Arendt’s37 analysis suggests that loneliness has far-reaching consequences, affecting not only individuals but the very fabric of society.

Overall, loneliness is not merely a personal adverse emotion; its effects can extend beyond the individual, influencing perceptions of society and challenging social cohesion. Although different conceptualizations of loneliness—from psychological frameworks to philosophical analyses—offer varied perspectives, they collectively indicate that, if left unaddressed, loneliness may contribute to broader societal issues.

The relationships between vegetation conditions in the living environment, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation are visually represented in Fig. 1. This study proposes two hypotheses grounded in the preceding discussions. These hypotheses aim to investigate the dynamic interactions among vegetation density and health, loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation. They are articulated as follows:

Theoretical model.

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

Vegetation density and health in the living environment positively influence an individual’s feelings of loneliness. This hypothesis posits that better vegetation conditions in one’s living environment contribute to reduced feelings of loneliness.

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

Loneliness impacts individuals’ perceptions of societal fragmentation. This hypothesis suggests that the experience of loneliness shapes how individuals perceive and interpret the fragmentation and division within their society.

Loneliness, vegetation conditions, and perceptions of fragmentation in the Korean context

Korea’s successful response to the COVID-19 pandemic can be attributed to the strategic implementation of a comprehensive set of public health policies77,78. The Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KDCA) adopted a multi-faceted approach, encompassing mandatory face mask usage in public spaces, the enforcement of social distancing guidelines, widespread diagnostic testing, meticulous contact tracing, and the establishment of stringent self-quarantine protocols79. Social distancing was first introduced in Korea on March 21, 2020, with enforcement levels reviewed biweekly based on infection and mortality rates80. The policy consisted of four or five stages, with higher levels imposing stricter restrictions, such as limits on gatherings, crowd capacities at sports events, mandatory electronic log systems, business hour restrictions, and bans on eating in indoor public spaces. These measures inevitably disrupted social interactions and daily routines. Cho et al.81 found a significant association between these restrictions and increased levels of depression during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. However, despite these restrictions, outdoor activities in open spaces such as parks remained permitted, leading to an increase in the frequency of short-distance walking as people sought safe opportunities for recreation and physical activity82.

In this context, Korea ranks 107th out of 167 countries in social capital according to the Legatum Prosperity Index83, reflecting a substantial gap compared to other established democracies. Social capital, driven largely by social trust, plays a pivotal role in shaping individual behavior and fostering societal cohesion24,25. Considering these dynamics, this study situates its analysis within the Korean context by examining relevant social and institutional factors that influence societal well-being and collective resilience.

The OECD’s 2020 definition of social support refers to the extent to which individuals have access to friends, relatives, or others they can rely on in times of adversity, serving as a measure of loneliness and social isolation within a country39. Analysis of 2019 data in Fig. 2 shows that Korea ranks among the lowest of OECD countries in terms of social support. This low ranking suggests that Koreans perceive their social support networks as notably weaker compared to those in other OECD countries, raising concerns about elevated levels of loneliness. The perceived lack of social support in Korea has significant implications, potentially exacerbating feelings of loneliness and leading to weakened community cohesion. These findings underscore the pressing need to address the root causes of loneliness in Korea and to implement targeted strategies at both individual and societal levels, particularly in light of urban inequality and spatial stratification within the country84,85,86.

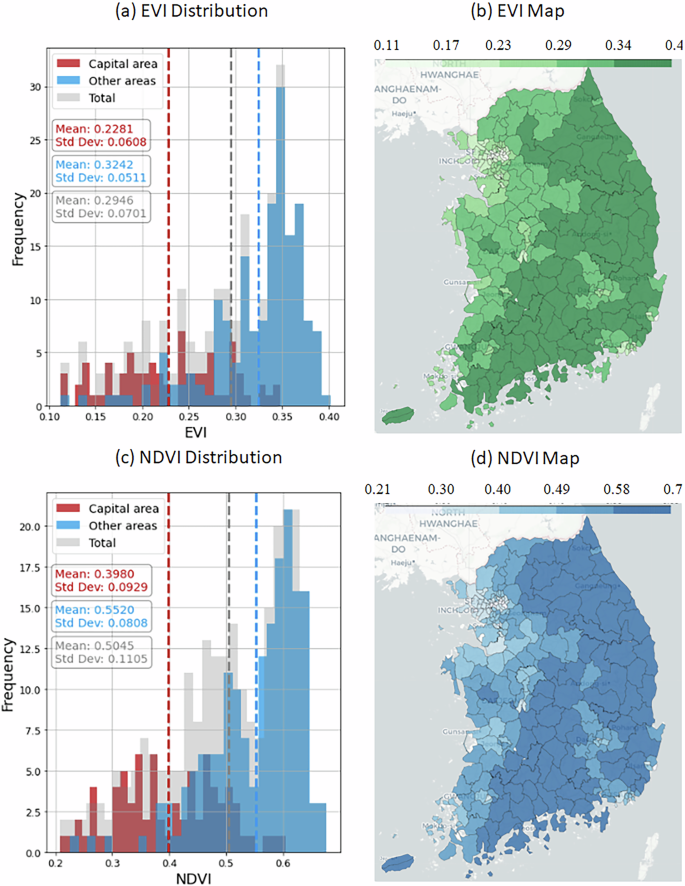

Figure 3 illustrates the distribution and spatial mapping of vegetation indices, specifically the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI) and the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), which assess vegetation density and health at the district (si-gun-gu) level (A comprehensive explanation of these variables is presented in the Methods section). The data indicate that these indices are significantly lower in the western region, particularly around Seoul, the highly urbanized and economically central capital, compared to the eastern and southern regions. This contrast suggests a clear spatial disparity in vegetation conditions, with urbanized areas experiencing lower vegetation density and health. Nationally, in panel (a), the average EVI is 0.29. In the metropolitan area, which includes Seoul, Incheon, and Gyeonggi Province, the average EVI is 0.22, while the rest of the country averages 0.32. Similarly, the national average NDVI is 0.5 in panel (c), with the metropolitan area averaging 0.39, compared to 0.55 in the rest of the country. Given that over 26 million people, or 50.6% of the country’s population, reside in the Seoul metropolitan area, a substantial portion of the population is concentrated in regions with lower vegetation indices.

a displays the distribution of EVI values in the capital area, other areas, and the total region, while b presentsa map illustrating this distribution. Similarly, c shows the distribution of NDVI values in the capital area, other areas, and the total region, with d providing a corresponding map representation.

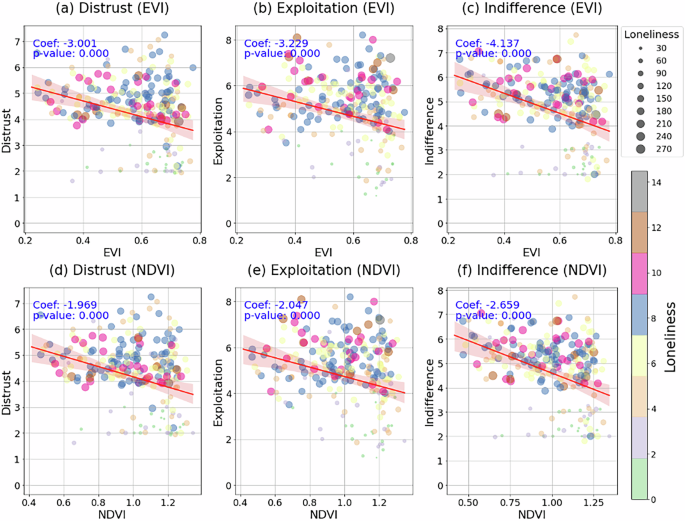

Figure 4 presents a scatter plot and regression line intuitively illustrating the relationship between the vegetation index and the average perceptions of fragmentation at the district level. This relationship, along with the detailed variables, will be explored in greater depth in the subsequent section. The figure provides a clear representation of how vegetation density and health are associated with perceptions of fragmentation, which encompasses sentiments such as distrust, exploitation, and indifference. The analysis indicates an inverse relationship between the vegetation index and perceptions of fragmentation. In all regression plots, the regression coefficients are negative, with p-values of 0.000, signifying statistical significance. Specifically, as the vegetation index increases, these negative sentiments tend to decrease. Additionally, when considering the variable of loneliness, a distinct pattern emerges: districts with higher levels of loneliness are positioned towards the top of the scatter plot, while districts with lower levels of loneliness are towards the bottom.

Scatter plots with regression lines illustrate the relationship between vegetation indices and the average perceptions of fragmentation at the district level. In particular, EVI is examined in relation to a Distrust, b Exploitation, and c Indifference. Similarly, NDVI is analyzed in relation to d Distrust, e Exploitation, and f Indifference. Additionally, the size and color of the dots represent the level of loneliness.

This pattern underscores the importance of further analysis to identify key drivers of the perceptions of fragmentation. It highlights the interaction between vegetation indices and broader social cohesion, suggesting that vegetation density and health can influence societal sentiments. This analysis warrants more investigations into how environmental factors contribute to social dynamics and the overall well-being of communities.

Analysis 1: district-level vegetation indices and their effect on perceived societal fragmentation

The first analysis examines the relationship between vegetation density and health, and the perceptions of fragmentation at the district (si-gun-gu) level. Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI), and Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) are calculated for each district and included as key variables. The perceptions of societal fragmentation are represented by the average value of survey responses aggregated at the district level. Detailed descriptions of the survey questions on societal fragmentation, including distrust, exploitation, and indifference, can be found in the methods and data subsection and Supplementary Table 3. Additionally, to account for potential confounding factors, this study incorporates data on local socio-economic characteristics, including urbanization rate, income level, and homeownership proportion, following established literature50. Additionally, air quality data, specifically PM10 levels, are included to control for their potential impacts on human health and the environment87,88 (refer to Supplementary Table 1 for details). The equation for analysis is formulated as follow:

The models evaluate the impact of vegetation indices on perceptions of societal fragmentation, controlling for key socio-economic and environmental factors. Employing a fixed effects approach, the models adjust for unobserved heterogeneity across entities, such as regional, demographic, and environmental characteristics, enabling a more precise estimation of the independent variables’ effects on the dependent variables. Specifically, ({{rm{Fragmentation}}}_{{rm{it}}}) represents the dependent variables, perceptions of fragmentation such as distrust, exploitation, and indifference, for district i at time t. ({{rm{Vegetation; index}}}_{{rm{it}}}) represents the vegetation index (either, EVI, or NDVI) for district i at time t. ({{mathsf{X}}}_{{rm{it}}}) is a vector of control variables. ({{rm{alpha }}}_{{rm{i}}}) is the district-specific fixed effects, capturing unobserved heterogeneity.

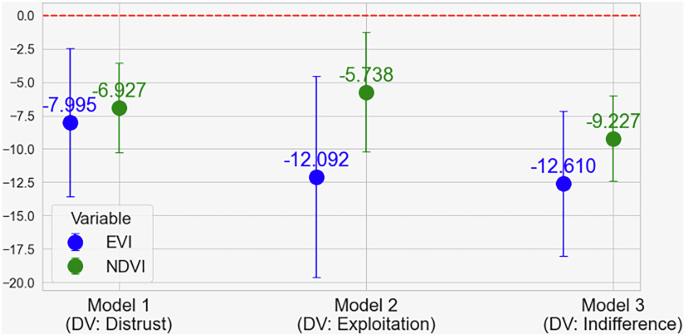

In Fig. 5, all vegetation density and health indices—EVI and NDVI—are statistically negative and significant at the 5% level or less. This indicates that higher vegetation indices are associated with lower average levels of perceptions of fragmentation, including distrust, exploitation, and indifference, in a district. Although the influence of each variable on the dependent variable differs, the confidence intervals suggest that these differences are not statistically significant.

Coefficient plots with 95%. Controls are not reported. Please see Supplementary Tables 6, 7, and 8 for full results.

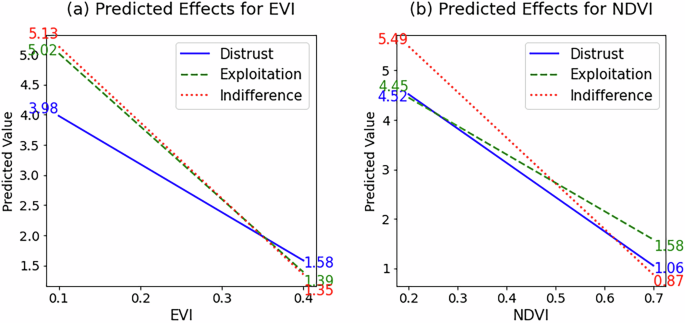

Figure 6 illustrates the predicted values of societal fragmentation perceptions while controlling for other variables at their mean values. In Fig. 6(a), as EVI increases from its minimum to maximum value, the predicted levels of distrust (from 3.98 to 1.58), exploitation (from 5.02 to 1.39), and indifference (from 5.13 to 1.35) show a significant decline. Similarly, Fig. 6(b) demonstrates that an increase in NDVI results in a marked decrease in the predicted values of distrust (from 4.52 to 1.06), exploitation (from 4.45 to 1.58), and indifference (from 5.49 to 0.87). Although these predicted values represent hypothetical scenarios rather than actual changes, the pronounced decrease in perceptions of societal fragmentation associated with improvements in vegetation indices is noteworthy and highlights the potential impact of enhanced green space on community cohesion.

An illustrationof the predicted values of societal fragmentation perceptions as a EVI and b NDVI change, while controlling for other variables at their mean values.

Analysis 2: impact of vegetation density on loneliness and societal fragmentation: a multilevel regression approach

The path analysis, presented in Supplementary Fig. 3, illustrates the hypothesized pathway between vegetation conditions, loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation. Building on this framework, the second analysis focuses on investigating the individual-level dynamics between vegetation conditions, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation using multilevel regression models. Specifically, it first explores the relationship between vegetation indices and feelings of loneliness. Subsequently, the analysis examines the connections between loneliness and each of the societal fragmentation indicators: mistrust, exploitation, and indifference.

Additionally, by including individual-level control variables (such as sex, marital status, age, education, income, homeownership, and religion52) and year fixed effects, the model controls for potential confounding factors that might influence outcomes (refer to the data subsection for detailed information on the survey and to Supplementary Tables 2 and 3 for a comprehensive description of the variables). This isolation of the effects of vegetation indices enhances the robustness of our findings. Overall, multilevel regression provides a comprehensive framework for understanding the interplay between environmental and individual factors in shaping feelings of loneliness and perceptions of societal fragmentation. Thus, the first and second regression model equations are formulated as follows:

For Eq. (2), ({{rm{Loneliness}}}_{{rm{ij}}}) is the loneliness score for individual i in district j. For Eq. (3), ({{rm{Fragmentation}}}_{{rm{ij}}}) (i.e., distrust, exploitation and indifference) is the fragmentation score for individual i in district j. For both equations, ({{rm{Vegetation; index}}}_{{rm{ij}}}) is the vegetation index (i.e., EVI, NDVI) for individual i in district j. ({{mathsf{X}}}_{{rm{ij}}}) is a vector of control variables including sex, marital status, age, education, income, homeownership, and religion. ({delta }_{{rm{year}}}) represents year fixed effects. ({upsilon }_{0{rm{j}}}) is the random intercept for district j. ({upsilon }_{1{rm{j}}}) is the random slope for vegetation index in district j. The models investigate the impact of vegetation indices and feelings of loneliness on societal fragmentation, controlling for individual-level socio-economic and demographic variables, as well as year fixed effects. Model (2) examines the effect of vegetation index on feelings of loneliness, while Model (3) explores how feelings of loneliness influence the perceptions of societal fragmentation. Both models include random intercepts (({upsilon }_{0{rm{j}}})) and random slopes (({upsilon }_{1{rm{j}}})) for the vegetation index to account for unobserved heterogeneity at the district level. The results are presented in Fig. 8.

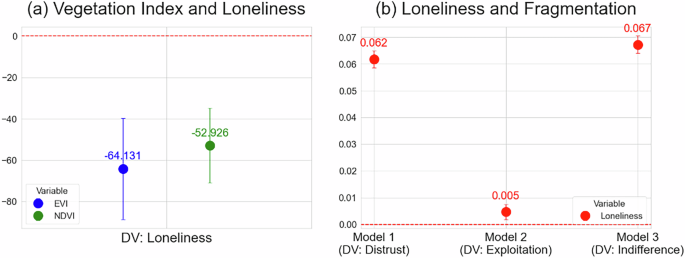

The results depicted in Fig. 7(a) demonstrate that both EVI and NDVI are statistically significant predictors of loneliness, with both indices exhibiting a negative association at the 5% significance level or lower. This finding suggests that individuals residing in areas with higher vegetation levels tend to experience lower levels of loneliness. Furthermore, Fig. 7(b) reveals that loneliness is a significant positive predictor of perceptions of societal fragmentation, including feelings of distrust, exploitation, and indifference, with each aspect being statistically significant at the 5% level or lower. Notably, the condition of vegetation emerges as a crucial factor initiating the dynamics between loneliness and perceptions of societal fragmentation.

Coefficient plots with 95%. Controls are not reported. Please see Supplementary Tables 9 and 10 for full results.

These results collectively indicate that enhanced vegetation conditions are associated with reduced loneliness, which, in turn, appears to decrease the likelihood of individuals perceiving society in a fragmented and negative manner. The analysis highlights the mediating role of loneliness in contributing to societal fragmentation, as evidenced by increased perceptions of distrust, exploitation, and indifference. The pronounced influence of loneliness suggests that individuals experiencing this emotion are more likely to mistrust their fellow citizens, perceive society as highly exploitative, and feel that people are generally unsupportive and indifferent toward one another.

Drawing upon the theoretical framework and arguments presented in this study, the integrated results from Analyses 1 and 2 collectively elucidate the relationship between vegetation density and health, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation. These findings consistently reveal a discernible pattern across both individual and district levels, underscoring the interconnectedness of environmental factors and social cohesion, and emphasizing the mediating role of loneliness in this relationship.

Discussion

In this study, two complementary analyses were conducted to investigate the relationship between vegetation density and health, feelings of loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation, with a particular emphasis on the mediating role of loneliness and how individual-level dynamics manifest in district-level patterns.

The research integrates macro-level structural factors with micro-level individual dynamics to identify key drivers of societal fragmentation and to explore the interaction between individual perceptions and broader social cohesion. The first analysis employed a fixed effects regression model to assess the impact of vegetation indices on average perceptions of fragmentation at the district level. This district-level analysis provided insights into how individual perceptions of societal fragmentation are shaped by environmental factors within local contexts, thereby highlighting the broader community-level outcomes.

The second analysis employed multilevel estimations to explore these relationships at the individual level, focusing on the association between vegetation indices and feelings of loneliness, as well as how loneliness mediates perceptions of societal fragmentation. This approach elucidates the underlying mechanisms, highlighting the pivotal role of vegetation density and health in mitigating loneliness and shaping societal perceptions. The findings underscore loneliness as a crucial mediating factor in the relationship between vegetation conditions and perceptions of social cohesion.

Before engaging in a comprehensive discussion of the implications, this study acknowledges several methodological constraints and limitations. The primary focus was to investigate the effects of vegetation conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period of temporal crisis, within a social context characterized by low social support, where the role of green spaces may be more pronounced89. However, the timing of the survey—conducted during the height of the pandemic—raises questions about the generalizability of the findings to non-pandemic periods. The study is also specific to Korea, a society with the lowest perceptions of social support among OECD nations. While this study offers valuable insights within the unique temporal and spatial context of Korea, a comparative approach would help determine whether the observed outcomes are specific to Korean society or indicative of more universal patterns.

While remote sensing vegetation indices provide valuable insights into the vegetation density and health of districts, they are subject to certain limitations. These indices often fail to capture the accessibility or specific types of green spaces available to the public. Their two-dimensional nature overlooks vertical green features, such as tree canopies, and may miss smaller urban elements like buildings or minor vegetation patches, reducing the precision of urban green space assessments. Future research should incorporate advanced technologies like LiDAR to capture three-dimensional vegetation structures and integrate remote sensing data with ground-level information on public access and usage patterns for a more comprehensive understanding of vegetation’s social and environmental impacts.

The second analysis employed multilevel regression models to account for individuals nested within broader vegetation conditions. However, the analysis was constrained by data availability, as specific residential locations were only accessible at the district level. Using spatial metrics such as network or Euclidean distance could have enabled more precise spatial analysis. Additionally, the extent of individuals’ actual exposure to green spaces (e.g., time spent walking in parks) was not captured, limiting behavioral context. Future studies should address these gaps by collecting more granular spatial and behavioral data through experimental designs and refined spatial metrics.

The relationships identified in this analysis should be interpreted cautiously, as they do not necessarily imply causality. To strengthen the findings, this study combined district-level analysis (Analysis 1) with individual-level analysis (Analysis 2) and conducted path analysis (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4) to clarify variable relationships. While results suggest a potential association between vegetation conditions, loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation, they do not establish direct causality. Individuals in areas with better living conditions may face fewer negative exposures, reducing negative emotions independently of vegetation presence. Moreover, unobserved factors may influence the observed associations, raising the possibility that the relationship between vegetation conditions and perceptions of societal fragmentation could reflect a spurious correlation driven by broader socio-economic advantages.

Despite controlling for socio-economic variables, including air pollution, and using fixed effects modeling at the district level and mixed-level modeling at the individual level to address unobserved heterogeneity, causal inferences remain limited. Additionally, while urbanization was included as a control variable, more specific metrics such as population density and traffic-related indicators were omitted, constraining the comprehensiveness of the controls. Following the principle outlined by Hünermund and Louw90, focusing on principal variables and simplifying the model can clarify key mechanisms. This approach helps distill core findings and guide more detailed and methodologically rigorous investigations. Future research should adopt more robust methodologies to disentangle these complex relationships and deepen understanding of the interplay between vegetation conditions and social perceptions.

This study emphasizes the urgent need for policy measures that improve vegetation conditions in living environments and advocates for a broader societal dialogue on loneliness to strengthen social cohesion. The establishment of a Minister of Loneliness in the U.K. in 2018 and Japan in 2021 underscores the growing recognition of loneliness as a critical social issue requiring direct intervention and collective societal attention. These developments highlight that loneliness is not merely an individual experience but is deeply connected to societal health, with significant implications for social cohesion and stability.

While green spaces alone may not fundamentally resolve the pervasive negative perceptions that persist across the nation, especially during times of crisis, they can play a crucial role in alleviating such perceptions. Addressing loneliness through public initiatives, rather than leaving individuals to manage it alone, could be essential in mitigating its broader social impact. The study suggests that a public approach to combating loneliness—through enhancing vegetation density and health, creating more green spaces, and urban parks, and supporting these efforts with targeted policy measures—holds substantial potential for improving social cohesion.

Methods

Methods

This study advances the understanding of the interplay between individual perceptions and broader community-level outcomes by exploring how personal experiences of loneliness impact social cohesion within districts characterized by varying levels of vegetation. The analysis aims to support Hypotheses 1 and 2 by first demonstrating a relationship between vegetation conditions and perceptions of societal fragmentation at the district level and, second, by identifying the mechanisms through which loneliness serves as a mediator at the individual level. By combining macro-level regression analyses with individual-level analyses, we provide robust evidence for the hypothesized models and uncover the potential mechanisms through which vegetation density and health influence social cohesion, with loneliness functioning as a key mediating factor. Additionally, in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4, we employ path analysis, a subset of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM), to illustrate the pathways connecting vegetation conditions, loneliness, and perceptions of societal fragmentation.

The first analysis utilizes a fixed effects regression model to assess the impact of vegetation indices on the average level of societal fragmentation across districts. This approach allows for an examination of how individual-level patterns of loneliness and fragmentation manifest within different local contexts, providing insights into how environmental factors shape community-level outcomes. The use of a fixed effects model is essential for controlling unobserved heterogeneity across districts that might influence societal fragmentation. By accounting for district-specific characteristics that remain constant over time, the model more accurately isolates the effects of vegetation indices, ensuring that the observed relationships are not confounded by other factors, such as socio-economic or regional differences. This focus on within-district variations enhances the validity of the findings, offering a clearer understanding of the role of environmental factors in shaping societal outcomes.

The second analysis employs multilevel regression models, also known as mixed-effects models, to account for both individual- and district-level effects. This approach considers fixed effects of individual-level predictors while modeling random effects at the district level through random intercepts and slopes, capturing district-specific deviations. Multilevel regression is particularly well-suited for hierarchical data structures, such as individual-level loneliness nested within district-level vegetation contexts.

District-level vegetation indices (EVI, NDVI) offer a meaningful representation of environmental exposure by capturing broader ecological characteristics within individuals’ living environments. These indices reflect the overall greenness context experienced through daily activities, including commuting, social interactions, and outdoor recreation91. Given that environmental exposure extends beyond immediate residential surroundings, district-level vegetation measures serve as relevant proxies for assessing how greenness influences social perceptions and well-being. This approach is particularly relevant in Korea, which had a population density of approximately 527 people per square kilometer in 2021, according to the World Bank92—one of the highest among OECD and advanced economies—emphasizing the crucial role of urban green spaces in mitigating environmental and social challenges in densely populated settings.

By incorporating random effects at the district level through random intercepts and slopes, the analysis captures cross-level interactions between district-level vegetation and individual experiences, offering a robust framework for evaluating contextual environmental influences. The inclusion of random intercepts and slopes further accounts for unobserved heterogeneity across districts, ensuring more precise and reliable estimates of vegetation indices’ fixed effects.

Data

This study employs a multi-level analytical framework combining district- and individual-level data. For the district-level analysis, the vegetation index derived from remote sensing data is integrated with socio-economic and air pollution indicators obtained from national sources such as Statistics Korea. The individual-level analysis uses comparable variables from the Korean Happiness Survey, conducted by the National Assembly Futures Institute, a public think tank affiliated with the National Assembly, between 2020 and 2021.

Both analyses incorporate variables capturing perceptions of societal fragmentation, based on responses from over 60,000 individuals surveyed in the Korean Happiness Survey. Designed to provide nationally representative data on happiness, inequality, and related determinants, the survey aligns with OECD guidelines for measuring subjective well-being. It includes questions on attitudes, beliefs, social values, and activities, offering insights into social-psychological factors influencing happiness.

Data collection for the Korean Happiness Survey took place from August to October 2020–2021 through door-to-door interviews with pre-designated respondents using tablet PCs. The sampling employed a nationwide, multi-stage stratified cluster design, featuring Probability Proportionate to Size (PPS) sampling at the district level and random sampling at the household level. Detailed variable definitions are presented in Supplementary Table 1 and 3.

In this study, we aim to obtain annual greenness metrics for each administrative district by leveraging three satellite-derived indices: the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), and the Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI)6. These indices were sourced from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) aboard the Terra and Aqua satellites, covering the period from 2020 to 2021.

For NDVI and EVI, which are designed to minimize canopy background variations and maintain sensitivity in densely vegetated areas, we utilized the MODIS/Terra vegetation indices product (MOD13Q1.061). This product offers spatial and temporal resolutions of 250 meters and 16-day intervals, respectively. The greenness data derived from these satellite-based indices were aggregated to yield mean annual values for each administrative district.

-

(a)

Enhanced Vegetation Index (EVI): EVI is designed to optimize the vegetation signal by correcting for canopy background signals and reducing atmospheric influences, including those from aerosols. EVI is particularly useful in areas with dense vegetation, where it improves sensitivity to variations in vegetation. The formula for EVI is:

$${rm{EVI}}={rm{G}}times frac{({rm{NIR}}-{rm{RED}})}{{rm{NIR}}+{{rm{C}}}_{1}times {rm{RED}}-{{rm{C}}}_{2}times {rm{BLUE}}+{rm{L}}}$$Where NIR is the near-infrared reflectance, RED is the red reflectance, BLUE is the blue reflectance, L is the canopy background adjustment, and G, ({{rm{C}}}_{1}), and ({{rm{C}}}_{2}) are coefficients.

-

(b)

Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI): NDVI is a widely used index that measures the difference between near-infrared (which vegetation strongly reflects) and red light (which vegetation absorbs). NDVI values range from −1 to +1, with higher values indicating healthier and denser vegetation. The formula for NDVI is:

To ensure conceptual clarity, this study uses the terms ‘vegetation density and health,’ and ‘vegetation conditions’ interchangeably within the context of environmental assessment. ‘Vegetation density and health’ describe the extent and vitality of vegetation within a specified area, measured through remote sensing indices (EVI, NDVI) reflecting coverage and greenness. The broader term ‘vegetation conditions’ encompasses both vegetation density and health, representing the overall quality of the natural environment.

In this study, loneliness is proposed as a mediating variable between vegetation index and perceptions of fragmentation. According to Perlman and Peplau66, loneliness is a distressing experience resulting from perceived deficiencies in social connections. They describe it as a subjective negative emotional response that occurs when social interactions fail to meet an individual’s expectations, highlighting its complexity and significant implications for both individual well-being and societal health. The frequency with which a respondent experiences loneliness in their daily life, as reported in the survey, serves as an estimate of their overall level of loneliness.

Variables such as distrust, exploitation, and indifference, extracted from survey data, serve as proxies for perceptions of societal fragmentation. This methodological approach is based on the theoretical construct depicted in Fig. 1, where these variables are hypothesized to be interconnected. Perceptions of societal fragmentation can manifest as disbelief, exploitation, and indifference—distinct yet interconnected responses to a society perceived as fragmented or divided.

-

(a)

Distrust: Refers to skepticism or a lack of faith in the integrity and functionality of societal structures93. In a fragmented society, individuals might doubt the effectiveness of social institutions, question the fairness of societal norms, or feel skeptical about the motives and actions of fellow citizens.

-

(b)

Exploitation: In a fragmented society, individuals might perceive or experience exploitation, defined as the unfair or unethical use of someone or something for one’s advantage94. This perception can arise in contexts where inequalities are stark, leading to beliefs that certain groups are being exploited. It can also emerge in situations where there is a perceived lack of mutual support and solidarity within the community.

-

(c)

Indifference: Characterized by a lack of interest, concern, or sympathy towards societal issues or the plight of others95. In a fragmented society, individuals may become apathetic, feeling disconnected from the broader community or believing their actions have little impact on societal outcomes. Indifference can be a coping mechanism against the overwhelming nature of societal problems or a response to perceived inefficacy in effecting change.

Responses