Functional assessment of autologous tissue expansion grafts for vaginal reconstruction in a rabbit model

Introduction

The human vagina is prone to various types of morphological abnormalities. Among them are several distinctive congenital conditions such as Mayer-Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome affecting approximately one in 5000 new-born females annually, and is characterised by underdeveloped reproductive organs including vaginal atresia1. Other rarer anomalies, such as androgen insensitivity syndrome, persistent cloaca or cloacal-exstrophy can all can culminate in a degree of vaginal atresia or agenesis2. Radiation treatment for cervical cancers or adjacent organs may also result in prolonged side effects causing secondary vaginal structural defects3.

The standard response to vaginal atresia has often been non-invasive intervention in the form of Frank’s dilatation treatment, which entails inserting dilators in the introital dimple with increasing length and diameter4. However, it may not be effective in the more severe cases, necessitating surgical alternatives. Procedures range from the semi-invasive traction devices, such as the Vecchietti procedure, to more complex reconstructive surgeries using the patient’s own bowel, skin, or buccal mucosa for grafting. Still, all the techniques carry potential side effects including graft failure, fistula formation, excessive mucus, laparotomy complications, pain, infection and scarring, underscoring the need for alternative grafting techniques with improved biocompatibility and reduced adverse effects5.

As a result, tissue engineering has been identified as a tool for developing new potential therapies2. Over the past two decades, the field of vaginal tissue engineering has blossomed, showcasing a proliferation of innovative strategies aimed at tackling vaginal malformations. A spectrum of methods, exploring the use of both synthetic materials and biological scaffolds, have come under examination in both in vitro and in vivo studies6. A clinical pilot study involving four patients with MRKH syndrome showed long-term functionality of autologous tissue cultured small intestinal submucosa grafts, indicating, that these methods can be translated from bench to beside7. Yet, despite the promising results unveiled nearly a decade ago, the adoption of these techniques as standard clinical treatment options remains absent. The reasons for this are manifold and complex, encompassing not only the scientific challenges inherent in the tissue engineering field but also considerations around cost, accessibility, and regulation. Conventional tissue engineering relies on complex, multi-step culture processes in GMP-certified facilities, creating a clinical gap due to limited availability8. This study introduces an emerging regenerative approach that bypasses these resource-intensive steps, aiming to make advanced tissue engineering more feasible in clinical settings.

The method, known as Perioperative Layered Autologous Tissue Expansion (PLATE) graft9, draws on micrografting principles adapted by Meek in 1958, who demonstrated that minced skin autografts could be used for skin expansion in burn patients10. We have expanded on Meeks’s established method for tissue repair, and explored novel applications of the technique for expansion of other organs bearing an epithelium such as the urinary bladder, oesophagus, uterus and vagina in both porcine and human tissues9,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. PLATE grafts are engineered by placing minced tissue particles onto either side of a biodegradable polyglactin 910 mesh (Vicryl®) and embedding the construct in collagen type I gel. After the gel has solidified, the construct is compressed, and the graft, which can be made in 30 min, is ready for surgical implantation. We have previously performed detailed in vitro assessments of PLATE grafts in eight different organs including clinical tissue samples from paediatric patients with congenital malformations including structural analysis, biomechanical performance, degradation analysis, and permeability assays9.

Our in vivo experiences with the methodology include an explorative tolerability study in rats, where we inserted epithelial grafts under the skin for histological and biomechanical evaluation after four weeks18. We also completed a pilot rabbit study where we inserted vaginal grafts in two healthy rabbit vaginas to showcase integration and tolerability for two and four weeks9. Parallel efforts have been made in a larger animal model with a pilot experiment for conduit urinary diversion in minipigs, where tissue grafts were well-integrated with the bladder and urinary tissue regeneration was observed on the grafts over three weeks19,20.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the regenerative, transcriptomic, and functional outcomes of the PLATE graft for vaginal reconstruction, comparing the potential benefits to acellular grafts or sham surgery across several checkpoints and extending to a long-term endpoint after seven months. In doing so, we present the outcomes of our first large-scale animal study applying the PLATE graft technique.

Results

Vaginal reconstruction and graft preparation

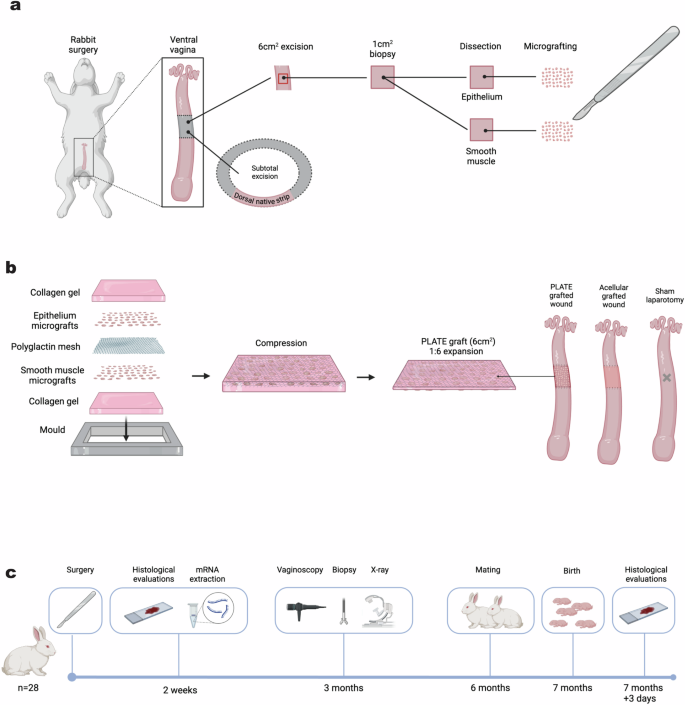

Twenty-eight rabbits underwent the laparotomy procedure where a subtotal excision of 20 × 30 mm was removed from the ventral vaginal wall leaving behind a dorsal native strip of vaginal tissue of circumferential length 10.8 ± 2.4 mm (PLATE graft animals) or 13.3 ± 2.7 mm (acellular graft animals), p = 0.53. From the excised vaginal segment, a piece of approximately 1 cm2 was dissected into epithelium and smooth muscle components, which were minced into 1.5 mm2 micrografts (Fig. 1a). PLATE grafts, with epithelium on the future luminal side and muscle the external side of the graft, were prepared at a 1:6 tissue expansion ratio. The vaginal defect was reconstructed with a PLATE graft (n = 11) or an acellular graft (n = 9), and additional rabbits underwent a sham laparotomy procedure (n = 8) as native controls (Fig. 1b). Ten rabbits were euthanised and analysed histologically and with mRNA sequencing after two weeks (4 PLATE, 3 acellular and 3 controls), and the remaining 18 rabbits were followed sequentially with x-ray, vaginoscopy, and a mating and birth trial before final histology after seven months (Fig. 1c).

a Rabbits underwent laparotomy and a subtotal vaginal excision of 20 × 30 mm was removed. A 1 cm2 section was dissected into epithelium and muscle, and minced. b The micrografts were added to either side of a polyglactin mesh (muscle on one side and mucosa on the other). The construct was embedded in collagen gel and compressed for five minutes. 20 × 30 mm grafts with minced tissue particles (PLATE grafts) or grafts without minced tissue particles (acellular grafts) were inserted in the vaginal defects, and control animals underwent sham laparotomy. c 28 rabbits were randomised and included in the trial; 10 animals were euthanised for histology and trascriptomic analysis after two weeks, and the remaining 18 rabbits underwent diagnostic procedures after three months (X-ray, vaginoscopy, and biopsy), and mating and birth after six months before final histology at 7 months and three days.

Adverse events

Two animals did not complete the trial period; one was due to self-inflicted soft tissue damage of the abdomen on post-operative day one (PLATE graft animal), and the other was due to Clostridium piliforme infestation with multiorgan engagement (Tyzzer’s disease) 80 days after surgery (acellular graft animal). A vesicourinary fistula was identified during a two-week autopsy in one rabbit, likely due to the combined effects of severe bladder calcifications and an inappropriately placed suture penetrating both the vaginal and bladder lumens (PLATE graft animal). This suture was since omitted from future surgeries and no other fistulas were observed during autopsies. Finally, an abnormal angulating anatomical variation was identified during three-month vaginoscopy and confirmed during seven-month autopsy, causing exclusion from the birth trial (PLATE graft animal).

Macroscopic appearance

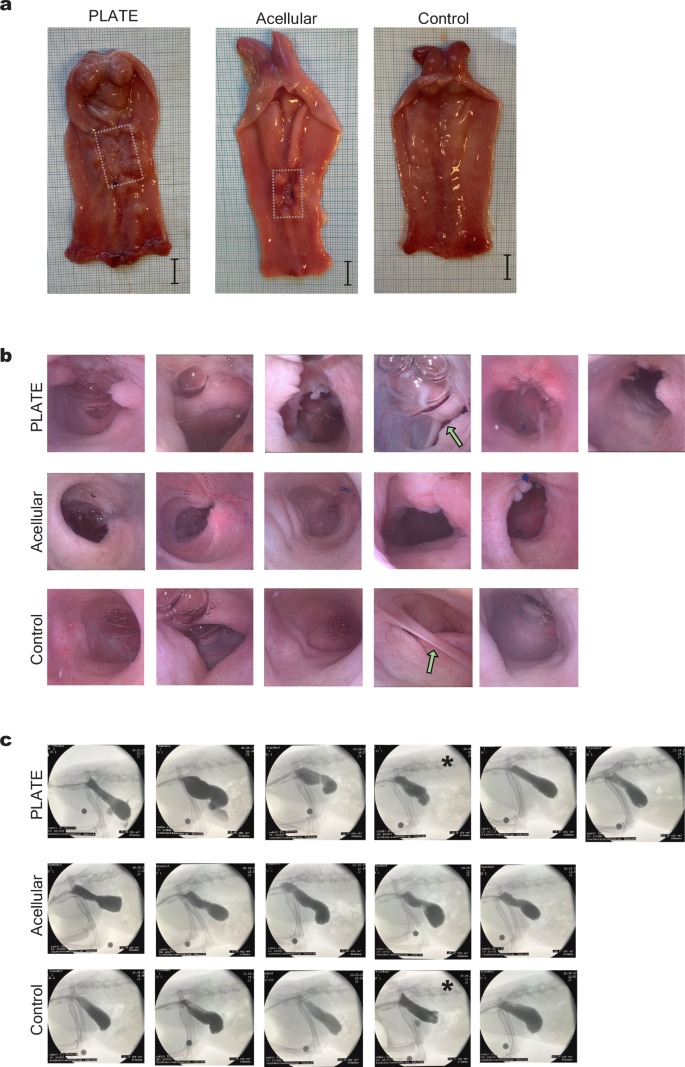

Post-mortem evaluations two weeks after the surgery indicated that the PLATE grafts were macroscopically well integrated within the vaginal wall (Fig. 2.a). The polyglactin mesh was still visible behind a translucent collagen layer, and some minced tissue particles could still be identified on the luminal side (Supplementary Fig. 1). The macroscopic appearance of vaginas with acellular grafts was similar to the PLATE grafted ones besides the absence of minced particles (not shown). Sham operated control rabbits demonstrated a vagina with smooth inner mucosa and no suture material. Three months after the surgeries, abdominal X-ray analyses with contrast injections and vaginoscopies were performed during brief sedation to assess the vaginal lumen and to determine if it was safe to proceed with the mating trial. X-rays showed no signs of fistulas or functional strictures in any animal neither in anterior-posterior or lateral views (Fig. 2c). Fibre-optic vaginoscopies confirmed these findings and offered clear views of the mucosal linings that covered all the graft zones in both PLATE and acellular graft recipients (Fig. 2b). We observed peristaltic contractions moving from the uterine outlets towards the vaginal introitus in all vaginas. In a PLATE graft animal, such a peristaltic wave, with contractive movements through the graft zone, was captured during combined vaginoscopy and live X-ray recording (Supplementary Movie). During post-mortem evaluations seven months after the surgery, the polyglactin mesh, collagen, and minced tissue particles were no longer macroscopically noticeable, and the graft zones had a similar gross appearance as the normal vaginas. All vaginas had an open lumen of at least 1,2 cm in diameter, and no stricture formation or fibrotic bands intervening with the luminal space could be identified. A rim of scar tissue was noted along the edges of the grafts, which were more distinct around the acellular grafts (Fig. 2a). Upon autopsy, we observed varying degrees of intraperitoneal adhesions in both grafted and control animals.

a Macroscopical appearances 7 months after surgery, showing the inside of three vaginal canals with uterine outlets in the top of the pictures. The dotted lines mark the edges of the graft zones with scar tissue rims. Scale = 1 cm. b Vaginoscopy images taken three months after surgery to assess luminal morphology around the graft zones, showing air bubbles, various degrees of scar tissue, but no strictures. Green arrows point at anatomical variations, the top arrow marks the vagina with an angulation, and the bottom arrow points at a septum between the two uterine outlets. c Three-month side view X-rays of contrast-filled vaginal cavities without signs of functional strictures in any of the subjects. The asterisks mark two vaginas with anatomical variations. As a reference, a circular scale was placed around the right knee joint, depicting 1 cm in diameter.

Microscopic evaluations of graft development

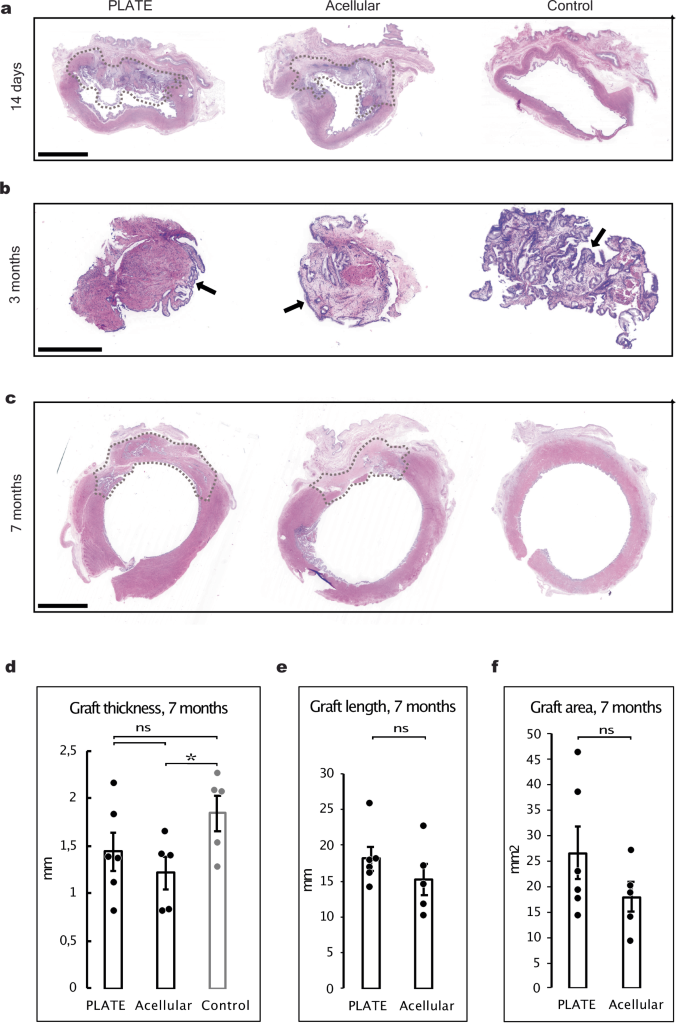

Two weeks after surgical insertion, both the PLATE grafts and the acellular grafts were densely populated with disorganised cells of varying phenotypes. In the PLATE grafts, minced muscle tissue particles were present (Fig. 3a). Along the luminal graft surfaces in both interventional groups, there were signs of neo-mucosal lining, as well as postoperative inflammatory reactions (Supplementary Fig. 2). The polyglactin mesh was still present at this time point and caused some tissue distortion (artefacts) during the histology preparation, impairing detailed comparative interpretation at this time point.

a Vaginal histology of transverse segments 14 days after surgery with patent graft zones (dotted areas) encircling approximately half of the vaginal lumen. Urinary bladder lumen with urothelium is present on the top of the transverse segments adjacent to the grafts. H&E, Scale bar: 5 mm. b Mucosal biopsies taken from the middle of the graft zones and from a similar representative area in control animals, during three-month vaginoscopies, showing epithelium and submucosa in all animals (arrows). H&E, Scale bar: 1 mm. c 7-month histological transverse segments of vaginal canals after opening for gross inspection, showing well-integrated graft zones (dotted lines) with tissue similar to native vaginal morphology. H&E, Scale bar: 5 mm. d Bar chart comparing thicknesses of graft zones and normal control vaginas after seven months, showing a significantly reduced thickness in acellular grafts vs. native controls. e Graft zone circumferential length in PLATE vs. acellular grafts after 7 months. f Transverse cross-sectional area of PLATE vs. acellular grafts after seven months. Error bars = SEM. *p < 0.05. ns = not significant.

Three months after surgery, mucosal biopsies were taken from the graft zones (or from a similar anatomical area in the control vaginas) during the vaginoscopy procedure. All biopsies showed mucosal lining with similar tissue morphology matching the control vaginas (Fig. 3b).

Seven months after surgery, the transition from graft zone to native vagina became more seamless, and the polyglactin mesh, collagen and minced tissue particles, that were formerly distinct, had become undistinguishable (Fig. 3c). The thickness of the vaginal wall within the PLATE graft zone was similar to the thickness of the tissue within the normal vaginal wall (1.4 ± 0.2 mm vs 1.8 ± 0.2 mm, p = 0.18) whereas the thickness of the acellular graft zones was significantly thinner than in the controls (1.2 ± 0.2 mm vs 1.8 ± 0.2 mm, p = 0.031) (Fig. 3d). There was not a statistical significance on the difference between the length of the graft zones in the PLATE or acellular animals (18.1 ± 1.6 mm vs 15.2 ± 2,2 mm, p = 0.31) (Fig. 3e). The total vaginal circumference, including both the graft zone and native strip, was 53.0 ± 6.1 mm in PLATE grafted animals, 48 ± 4.4 mm in acellular, and 43.2 ± 0.8 mm in native vaginas. PLATE graft zones and acellular graft zones accounted for 34% and 31% of that circumference, respectively (graft zones marked in Fig. 3a, c). Nor was there a significant difference between the graft transverse cross-sectional areas of PLATE grafts and acellular grafts (26.7 ± 5.3 mm2 vs 18.0 ± 3.0 mm2, p = 0.21) (Fig. 3f).

Gene-expression

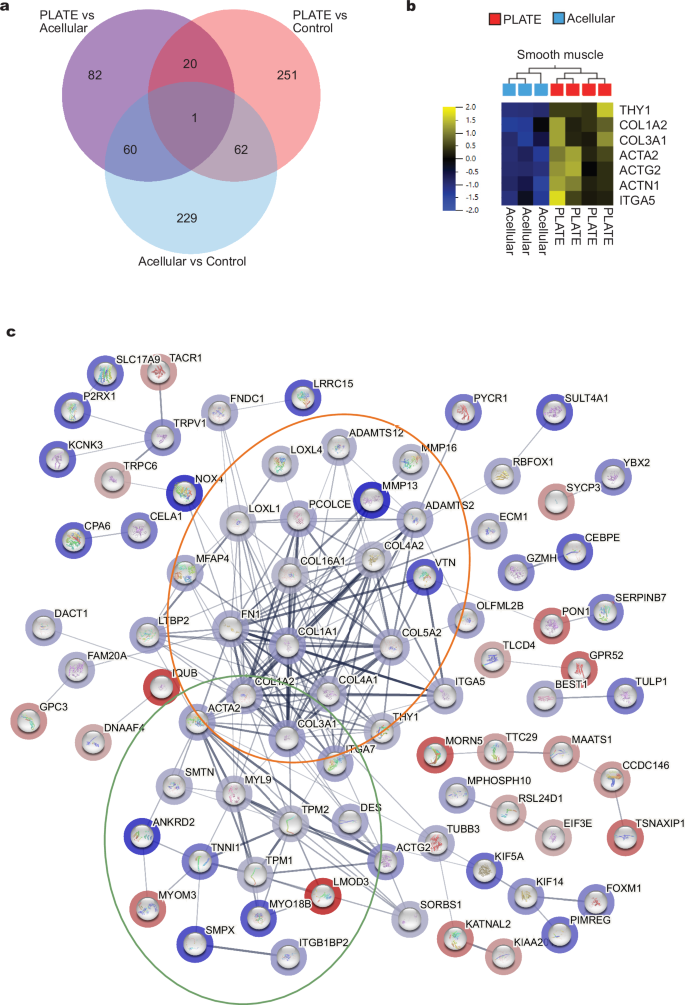

Biopsies 10 mm adjacent to the grafts were collected two weeks after the surgeries and mRNA expressions were sequenced. When studying the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the three different surgery groups, the largest number of DEGs were detected between acellular vs control (352 genes, 103 up and 249 down. Figure 4a, blue circle) and PLATE vs control (334, 241 up and 93 down. Figure 4a red circle). The only experimental difference between PLATE and acellular groups was the presence of autologous micrografts in the PLATE grafts, which resulted in 163 DEGs between the PLATE and acellular grafted vaginas (124 up, 40 down. Figure 4a, purple circle). According to proteinatlas.org, there are 41 smooth muscle signature genes and seven of them were significantly up-regulated in the PLATE vs acellular grafted vaginal wall biopsies (var < 0.1, p < 0.05, q = 0.15). The largest difference was observed in ACTG2, a gene coding for smooth muscle actin γ-2 (log2FC 2.17, p < 0.05, q = 0.06) (Fig. 4b). From the STRING network analysis and functional enrichment, 18 GO terms were identified, representing two main clusters of biological processes (Supplementary Table 1). One concerned the extracellular matrix (ECM) with collagen fibril organisation (GO:00300199), collagen metabolic process (GO:0032963) and ECM organisation (GO:0030198) among the strongest enriched categories (Fig. 4c, orange circle). Muscle contraction (GO:0006936) and muscle organ and structure development (GO:0007517 & GO:0061061) represented the other biological process (Fig. 4c, green circle).

a Venn diagram of differential gene expressions between the three surgery groups. b Heatmap of the 7 differentially expressed smooth muscle genes. c STRING network analysis of DEGs from PLATE vs. acellular grafts. Blue halos represent upregulated genes in the PLATE group and red halos represent upregulated genes in the acellular group, respectively. The orange circle mostly contains genes involved with ECM organisation. The green circle mostly contains genes involved in smooth muscle development.

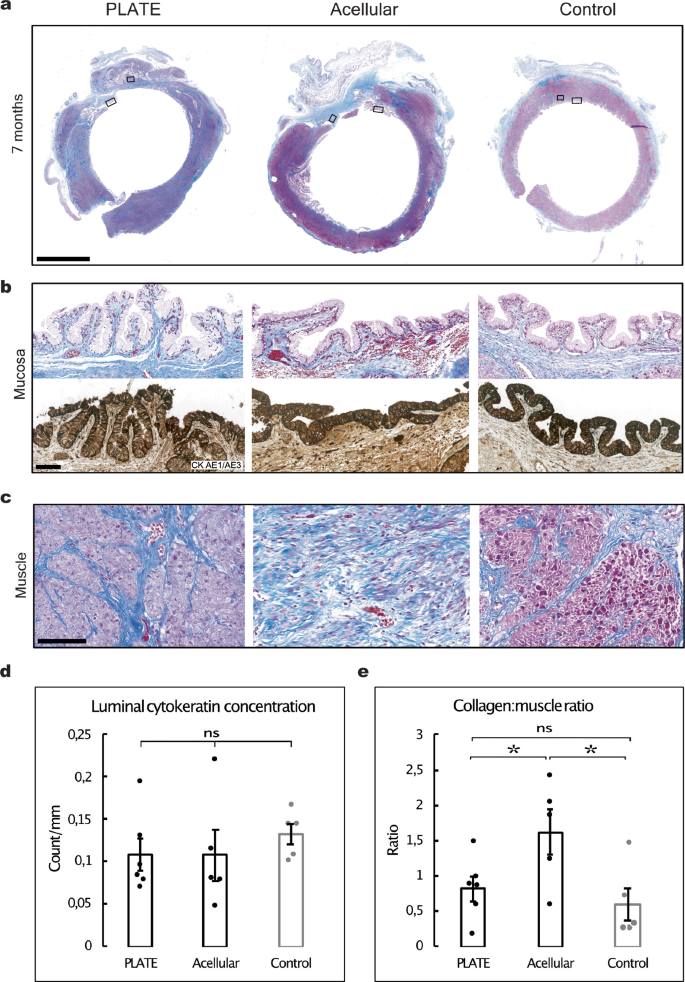

Long-term graft composition assessment

Seven months after insertion, the vaginal segments were assessed with Masson’s trichrome staining, to quantify relative muscle and collagen content, and pan-cytokeratin, to quantify epithelial regeneration. The PLATE grafts demonstrated several regions with fully developed and well-organised smooth muscle tissue (Fig. 5a, c). Vaginal mucosa was seen on the luminal surfaces of both the PLATE and acellular grafts (Fig. 5b), and the relative concentrations of cytokeratin (total area covered with positive signal per luminal mm) were similar between PLATE (0.11 ± 0.02 counts/mm), acellular (0.11 ± 0.03 counts/mm), and native vaginas (0.13 ± 0.01 counts/mm), and with no significant differences observed between neither PLATE vs. acellular (p = 0.98), PLATE vs. control (p = 0.34), or acellular vs. control (p = 0.46) (Fig.5d). The ratio between collagen and muscle tissue was significantly lower in the PLATE vs. acellular grafts (0.82 ± 0.18 vs. 1.62 ± 0.32, p = 0.0496). The ratio was also significantly lower between the native controls and the acellular grafts (0.59 ± 0.23 vs 1.62 ± 0.32, p = 0.033). We found no significant difference between the ratios in the PLATE grafts and native controls (0.82 ± 0.18 vs. 0.59 ± 0.23, p = 0.45) (Fig. 5e).

a Representative transverse vaginal segments seven months after surgery, showing muscle (pink) and collagen (blue). A larger degree of fibrosis (using collagen concentration as a proxy) was found in the acellular graft zones. Masson’s Trichrome. Scale bar: 5 mm. b Region of interest showing native-looking vaginal mucosa in all conditions. Masson’s trichrome (top) and pan-cytokeratin CK AE1/AE3 (bottom), Scale bar 100 μm. c Region of interest demonstrating a high degree of muscular regeneration in the PLATE graft zone. Masson’s trichrome, Scale bar: 100 μm. d Bar chart comparing luminal cytokeratin count pr. luminal mm, showing similar amounts across all conditions. e Bar chart illustrating a significantly higher ratio of collagen to muscle content in acellular vs. PLATE and acellular vs. control vagina. Error bars = SEM, ns = not significant, *p < 0.05.

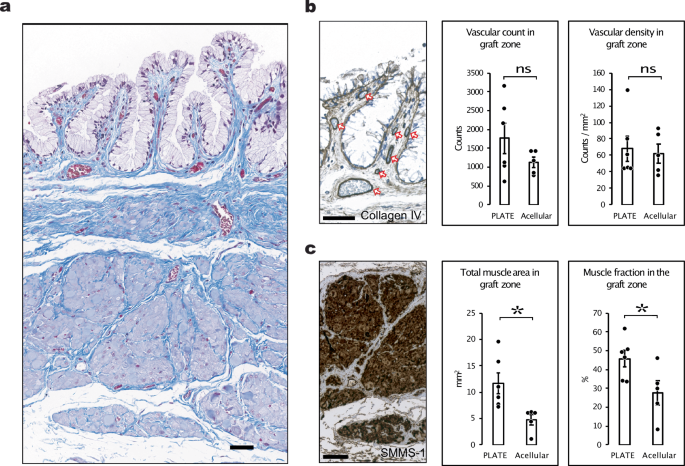

To further assess the degree of muscle regeneration after seven months, we performed immunohistochemical stains on smooth muscle myosin. There was significantly more smooth muscle within the PLATE graft zones than in the acellular graft zones, both in absolute terms (11.7 ± 2.0 vs 4.7 ± 1.0 mm2 smooth muscle, p = 0.018) and relative to the area of the graft (46 ± 4 vs 28 ± 6% muscle in the graft zone, p = 0.038) (Fig. 6a, c). We performed a manual quantification of vascular structures within the graft zones. There was not a statistically significant difference between the number of vascular structures within the PLATE graft zones versus the acellular graft zones, however, we noticed a higher count of vessels both in absolute numbers (1766 ± 407 vessels vs 1121 ± 136 vessels, p = 0.20) and relative to the size of the graft zones (68.2 ± 15.2 vs 62.3 ± 11.4 vessels pr. mm2, p = 0.77) (Fig. 6a, b).

a A representative area from the PLATE graft zone seven months after surgery including two regions of interest (ROI), Masson’s trichrome. b Collagen IV immunohistochemistry stain in the top ROI used for manual counting of vascular structures (orange arrows) represented as bar charts in absolute numbers (left bar chart) and relative to the area of the graft (right bar chart). c Smooth muscle myosin stain showing smooth muscle tissue within the PLATE graft zone. The smooth muscle area was quantified using machine learning and represented both in absolute values (left bar chart) and relative to the area of the graft zones (right bar chart). Error bars = SEM. *p < 0.05. ns = not significant. All scale bars = 50 μm.

Functionality of the vaginal canal

Nine rabbits were randomised for mating with a male six months after surgery (3 from each group). All rabbits became pregnant within the first attempted mating cycle. Around two days prior to delivery, the rabbits began plucking their fur and building breeding nests. After approximately 31 days, eight out of nine rabbits were able to complete natural vaginal delivery without complications (Table 1). The litter sizes and birthweights were similar between the groups. Moreover, stillborn and survival rates were similar or superior in the grafted animals than in the control animals (Table 1). One PLATE grafted animal was unable to deliver vaginally. At autopsy, the vaginal canal was revealed as stricture-free, but an adhesion in the peritoneal cavity was identified as blocking the normal mobility of the birth canal, causing obstruction from the outside (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

This study reports on the preclinical use of a PLATE graft for vaginal reconstructive surgery in a rabbit model. Observations spanning short, intermediate, and long-term intervals were assessed, and three experimental groups, inclusive of a control, were comparatively evaluated in a large animal model. The long-term tissue morphology was similar to native vaginal tissues concerning vaginal thickness and mucosal lining and showed high degrees of smooth muscle and connective tissue regeneration. Equally important, long-term functionality of the engineered vaginas mirrored that of native vaginas, as evidenced by successful conception and natural vaginal delivery. Despite the increased fibrosis and reduced muscle content present in the acellular graft recipients, these rabbits were also capable of natural vaginal delivery of live pups.

Macroscopically, the PLATE grafts were well-integrated throughout the study period. The three-month evaluations evidenced mucosal lining on all vaginas and an absence of functional strictures, despite the presence of scar tissue formation and smaller fibrotic bands. Final macroscopic evaluations underscored that PLATE graft zones were well-integrated into the natural vaginal cavity, mirroring the thickness of native tissues. Histologically we saw a seamlessly integrated graft with multi-layered and native tissue morphology with a high degree of smooth muscle regeneration. The PLATE grafts exhibited a collagen:muscle ratio akin to normal vaginas, unlike the acellular grafts, which showed a higher degree of fibrosis.

The RNA-seq analysis after two weeks provided a possible explanation for the enhanced muscle content in the PLATE graft recipients observed later on. Seven out of 41 known smooth muscle genes were differentially upregulated in the vaginal tissue from PLATE graft recipients two weeks after surgery, suggesting that micrografts may induce smooth muscle regeneration at this early stage. While there have been substantial advancements in our understanding of the micromolecular events that govern autologous micrografting, these have been focused on wound healing in skin and other organs, not in the vagina21,22. In our study, the observed gene upregulation in the PLATE graft recipients indicated an active and dynamic biological environment compared to the acellular ones, including structural protein production, cellular communication, and smooth muscle cell function. These changes are likely contributing to better integration and functionality of the PLATE grafts, supporting their use in vaginal reconstruction.

The technical investments required to adopt the method in a clinical setting are relatively small. The steel graft moulding kit (Supplementary fig. 5) is autoclaveable and the sterile nylon mesh is commercially available and inexpensive. Graft fabrication can be performed under the confines of a normal operating theatre fitted with a heating cabinet of 37°C. The collagen type I gel used in this study is not currently approved for human use, necessitating the testing of various commercially available collagen gel products for future applications. We optimised the method for in vivo conditions by placing the tissue particles directly on the mesh and embedding them inside the collagen instead of placing them on the outside of the collagen, as we have previously reported9. This way, fewer of the tissue particles fell off the graft during the implantation. This method optimisation has previously been validated in vitro and did not affect tissue regeneration19. We utilised 1:6 expansion ratio for the PLATE grafts, which was deemed appropriate for this first large animal experiment, however, the expansion ratio could possibly be increased in future experiments to expand scarcely available tissue in a clinical setting.

We left behind a native strip of vaginal tissue which accounted for approximately 1/3 of the engineered vaginas during the time of surgery. However, when assessing the morphology after seven months, the circumferential length of the native strip accounted for approximately 2/3 of the total vaginal circumference in the PLATE grafted animals. During that period, rabbits had become full-grown adults and the circumference of the vaginas had increased from of 29.2 ± 3.3 mm to 53.0 ± 6.1 mm in PLATE-grafted animals. The length of the PLATE graft zone, however, remained somewhat constant (the 20 mm wide graft that was inserted measured 18.1 ± 1.6 mm 7 months later). This tells us that PLATE grafts can be used in growing organs, which may play an important role in the surgical management of vaginal atresia, where the patients sometimes represent a paediatric or adolescent population4.

The PLATE graft technique diverges significantly from traditional tissue engineering methods which involve a series of resource-intensive steps such as initial tissue collection (often under surgery), subsequent cell isolation and proliferation, in vitro scaffold seeding, and bioreactor organ cultures23. Despite uniform cell seeding techniques, the type of scaffolds used in conventional vaginal tissue engineering appears to be a divisive factor24. These range from: synthetic biomaterials (PGA25); to biological scaffolds (Amnion, SIS26 or decellularised vaginas27); to methods not using external scaffolds such as seeding autologous cells on a gauze28 or the self-assembly method, where dermal fibroblasts produce their own extracellular matrix scaffold29. While the previous studies generally show promising results, including high Female Sexual Function Index scores, they all require the beforementioned resource-intensive steps, rendering them unfit for many clinical contexts7. The PLATE graft method, being a definitive perioperative procedure, requires none of those steps offering a less resource-intensive alternative. Thus, the study aimed to discern if the PLATE graft procedure was technically feasible in a large animal study, and could provide compelling results in terms of tissue-integration, regeneration, and functionality.

Emerging evidence suggests that vaginal reconstructive surgery, or complete neovaginas, can employ acellular grafts, negating the need for tissue culture methods. Commercially available scaffolds like SIS, Intercede® and PACIENA®, and naturally available allogeneic amnion, have all been tested in human candidates, yielding encouraging results30,31,32. This contradicts the prevailing belief that using acellular grafts exceeding the critical size defect of 1 cm2 will result in fibrosis25. Consequently, we incorporated an acellular study condition into our experimental model. Although acellular vaginas facilitated natural and uncomplicated vaginal delivery, they fell short in overall tissue morphology. Macroscopic and microscopic analyses highlighted the superiority of PLATE grafts over acellular counterparts. The extensive tissue regeneration observed in PLATE graft zones, marked by the robust formation of smooth muscle and collagen akin to native vaginal architecture, underscores the critical role of tissue particles in facilitating authentic regenerative processes.

One limitation of this exploratory study was that our study utilised healthy vaginal tissue in the animal model, leaving unknown how tissue regeneration and vaginal function would progress in a diseased model that could better represent female patients with malformed or strictured vaginas. The anatomical and functional differences between rabbit and human vaginas present challenges for translating these findings to humans. In rabbits, the vagina is located intraperitoneally, whereas in humans, it is extraperitoneal. Adverse events observed in this study, including Tyzzer’s disease, self-inflicted trauma, anatomical angulation, and peritoneal adhesions, are mostly related to the rabbit model. Human vaginal anatomy necessitates different surgical access approaches and may involve complications not addressed in this study. Additionally, a pregnant woman that has undergone complex urogenital surgery would be recommended caesarean delivery. Consequently, the methodology may need to be optimised accordingly, and prior to human translation, PLATE grafts should be assessed in a model including diseased tissues. Another limitation to mention is that this study did not explore all the active mechanical properties of the vaginal organ, which could add value in future studies33.

In summary, our findings demonstrate that PLATE grafts provide a viable, single-stage approach for vaginal reconstructive surgery in rabbits, addressing a critical need where traditional methods often yield suboptimal outcomes. With potential applications in conditions such as vaginal malformations, hollow organ atresia in paediatric populations, and gynaecologic oncology, this study establishes proof of concept for autologous tissue expansion in hollow organ reconstruction. Further research is needed to determine its applicability to human patients and to refine the method for clinical use.

Methods

Ethics

This study complies with international standards for animal experimentation and was reported according to the extended ARRIVE guidelines. The study protocol was approved by the Danish Inspectorate on Animal Experimentation (protocol number: 2021-15-0201-00982). The study was performed in an AAALAC accredited (American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care) experimental facility in accordance with current European legislations on laboratory use of animal subjects. To ensure animal welfare, we provided thorough postoperative care, and maintained optimal living conditions for the animals throughout the study. Prespecified humane endpoints were carefully monitored on a daily basis, as specified below. Preparatory in-vitro studies were conducted prior to in-vivo experimentation. By addressing a clinical gap in tissue engineering for vaginal reconstruction, this research aims to contribute directly to improved surgical options for patients with congenital or acquired vaginal malformations, while supporting the 3Rs principle (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) in ethical research.

Protocol registration

No protocol was registered prior to the experiment.

Sample size and experimental animals

Rabbits are relevant study-animals for vagina- and reproduction studies for their large vaginal size, their easy intraperitoneal surgical access, the fact that they are induced ovulators with high fertility and fecundity34. Biomechanically, the rabbit vagina also holds a large proportion of contractile vaginal smooth muscle cells, which makes it a good candidate for studying pelvic organ prolapse, the effects of mesh implantation, and menopause33. We chose rabbits of 17-19 weeks of age that are about 30% of their full body weight because we wanted to assess how grafts function in subjects who are still growing.

In light of the exploratory nature of this study, we did not have empirical data from which to extrapolate a conventional sample size calculation. Consequently, and with careful consideration of animal welfare and after clearance with the animal inspectorate, we were allowed to include the minimum number of animals required in the birth trial, and to ensure biological replication and to observe potential gross and micro-anatomical differences between the experimental groups. This preliminary approach allowed for foundational insights that can inform future, larger-scale investigations. In the main trial, we included 28 female White New Zealand rabbits, that were 17–19 weeks of age and 3.1 ± 0.33 kg of weight at the time of surgery. We also included two frozen tissue samples for RNA sequencing from two additional rabbits of the same species, age and gender, that were collected during the preliminary pilot experiment. We also included two male white New Zealand rabbits for mating purposes alone, one was a retired breeder of 3 years of age, and the other was a male of 19 weeks of age (Scanbur, DK). All rabbits were allowed at least seven days of acclimatisation before surgery or mating.

Randomisation and blinding

All randomisations were performed using the random.org true random number generator.

Rabbit cages (two siblings pr. cage) were randomised as blocks to receive either a graft procedure (n = 20) or sham surgery (n = 8), and both siblings were operated on the same day in order to prevent postoperative conflicts between sedated and non-sedated animals. Following cage randomisation, each animal within a graft cage was randomly assigned either a PLATE graft (n = 11) or an acellular graft (n = 9). During the study period, we detected a highly variable and unpredictable vaginal circumference between the rabbits, and consequently, treatment allocation by minimisation was used to ensure a balance between this important factor between the groups35. Randomisation was also used during the mating trial, where all of the eligible animals were randomised to mating or no mating. Three out of 16 rabbits were excluded from the mating trial. Two were excluded for aggressive behaviour towards other rabbits (one PLATE and one acellular graft animal) and one was excluded due to the angulating anatomical variation that was detected during the three-month vaginoscopy and X ray analysis (PLATE graft animal). Cage allocation was concealed and performed prior to arrival at the animal facility. One author had access to group allocation information during the trial (OW). Blinding was not used during surgery or during postoperative care for safety and animal welfare reasons. Blinding was applied during the data assessment where the investigators were unaware of which subtype of graft had been inserted.

Outcome measures

The following parameters were assessed: Survival data and adverse events were collected throughout the study. Two-week histology and gross morphology were used to determine if the surgical procedure was feasible and safe, before continuing with the trial. Vaginal tissue biopsies from the first surgeries and from autopsy at two weeks were used for mRNA sequencing. Three-month vaginal gross-morphology including biopsy and histology was used to determine if vaginal strictures were present which would exclude from the mating trial. Mating trials were performed to determine if rabbits could complete coitus, conceive, and complete natural vaginal delivery. Data concerning the well-being of pups were collected (weight, survival status). Seven-month vaginal morphology was assessed macroscopically (before or after cutting open the vagina), and microscopically (thickness, circumferential length, transverse cross-sectional area, collagen:muscle ratio, luminal cytokeratin concentration, vascular count and smooth muscle myosin content).

Pharmacological treatments

The anaesthesia protocol for surgery included induction with midazolam (0.2 mg/kg IM) and dexmedetomidine (0.02 g/kg IM) and buprenorphine (0.05 mg/kg IM) followed 5 min later by ketamine (6.5 mg/kg IM). Anaesthesia was sustained with sevoflurane (2.5% in 35% O2 inhalation) and fentanyl (5 μg/kg/h IV). A local injection of bupivacaine (1 mg/kg SC) around the incision was applied five minutes before the surgery and immediately after the surgery.

Postoperatively, the rabbits received buprenorphine (0.01–0.05 mg/kg/sc) two to three times a day for three days, metacam (1 mg/kg oral suspension) for four days, and antibiotics sulfadioxin/trimetrioprim (40/200 mg/ml–0.1 ml/kg SC) one day prior to surgery and four days post-surgery.

The sedation protocol for combined vaginoscopy, X-ray, and biopsy procedure was performed with Ketamine (15–30 mg/kg IM).

Surgical procedure

Rabbits were anaesthetised and intubated and placed in the supine position. The lower abdomen was trimmed and adhesive tape was used to remove remnant fur. The abdomen was sterilised with 70% alcohol rub and the operating field was, furthermore, covered with sterile transparent Leukomed film (Leukoplast, UK), sterile Foliodrapes 45 × 75 cm and 10 × 50 cm (Hartmann, DE) and a sterile Buster surgery cover 120 × 180 cm (Kruuse, DK). A 4–5 cm lower midline abdominal incision was made and holding sutures were placed on the edges of the facia (Prolene® 4-0, Johnson & Johnson). Anatomical structures were identified and the bladder was emptied through the exposed bladder wall using an 18 G syringe if needed. The vagina and urinary bladder were separated from each other with blunt dissection, and holding sutures were placed in each structure (Vicryl® plus 4-0, Johnson & Johnson). The vagina was exposed, and the circumference was measured using a ruler. A 20 × 30 mm segment was cut out from the anterior wall (facing the bladder) with scissors, leaving behind a native dorsal strip of tissue of varying size (approximately 1 cm) depending on the native circumferential length. In cases where the circumference was only 2 cm, a 5 mm dorsal strip was left behind, which occurred in two PLATE-grafted rabbits. Haemostasis was secured with bipolar diathermy. A piece of the excised segment (1/6) was used for graft fabrication (see below), and a small biopsy (5 × 5 mm) was collected for mRNA sequencing to serve as a healthy vaginal control. The engineered graft of 20 × 30 mm was inserted using a single stay suture at each of the four corners (Prolene® 4-0, Johnson & Johnson), and running sutures between the stay sutures (Vicryl® plus 4-0). The bladder was reattached to the vagina with three single sutures (Vicryl® plus 4-0), placed on the outside periphery of the graft zone. The muscular fascia was closed with running sutures (PDS® 4-0, Johnson & Johnson). The subcutis was closed with running sutures (Vicryl® plus 4-0) and the skin was closed with intracutaneous running sutures using a straight needle (Monocryl 65 mm 4-0, Johnson & Johnson). We applied tissue adhesive glue as a final step before applying the final local bupivacaine (1 mg/kg SC). Total operating time was approximately 2–3 h.

Graft fabrication

1 cm2 of the excised full-thickness vaginal tissue was used for PLATE graft fabrication, and the remaining tissue was discarded. The epithelium and smooth muscle layers were dissected using round-edged scissors and syringes to hold the corners of the tissue while dissecting. Each layer was minced on a 15 cm petri dish (Thermo Scientific, USA) using a round edged scalpel type 21 (Swan Morton, UK). The mincing method involved placing parallel cuts every 1.5 mm along the strip of tissue, followed by sequential orthogonal cuts every 1.5 mm, yielding approximately 40–50 minced tissue particles of both types from the 1 cm2 segment. The minced epithelium particles were distributed on the surface of a polyglactin mesh (VM1208 knitted Vicryl® mesh, Johnson & Johnson) precut into a 20 × 30 mm rectangular shape. The mesh was flipped, and the minced muscle particles were distributed on the other side. The construct was moved to a custom made steel mould twice the length and width of the graft (6 × 4 × 1 cm, length × width × height), and 24 mL of a liquid collagen type I solution (contents previously described in9) was poured into the mould suspending the polyglactin mesh in the middle. The mould was then placed inside a heating cabinet (Memmert, model 300, Germany) set at 37 °C for 10 min for collagen polymerisation. Prior to compression, either side of the construct was protected with a layer of sterile monofilament polyamide mesh (pore size 20 μm, Schwegmann, Germany). Perforated steel plates (custom made) were placed on either side of the construct, and a stack of sterile gauze for absorption was placed at the bottom. The graft was compressed for 5 minutes using the weight of the steel mould (290 g in total) (the graft fabrication kit is shown in Supplementary Fig. 5). Then, the polyamide mesh was peeled off and discarded. Excess collagen around the graft was trimmed using a scalpel, leaving a 1 mm rim that was then rolled onto the graft material to seal the edges and prevent collagen delamination. The finalised graft was transported to the surgical wound using forceps and inserted with the epithelial particles facing the lumen, and the muscle particles facing the outside (towards the bladder).

Acellular grafts were prepared in the same way; however, no minced tissue particles were added.

Vaginoscopy, biopsy, and x-ray procedures

Under ketamine sedation, rabbits were placed in a supine position. An arc X-ray unit was positioned, a 1 cm metal ball was fixated to the rabbit for scale, and a urinary catheter was placed into the vaginal vault. Contrast medium (Omnipaque 180 mg/ml) was injected into the vaginal cavity and images were captured. Then, the rabbit was repositioned onto its side for another x-ray image or video recording. The urinary catheter was replaced with a 16.2 Fr single-use flexible cystoscope (Ambu, Dk) for video vaginoscopy. Biopsies were collected from the central part of the graft zones using single-use flexible endoscopy forceps toward the end of the procedure.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Female rabbits of 17–19 weeks of age were included. Exclusion criteria included preterm death. Consequently, the two rabbits that died preterm were excluded from all data analysis.

Housing and husbandry

Female rabbits were housed in groups of two with a sibling, and male rabbits were single housed. Animals rabbits were housed according to standard Danish legislation to enable cognitive enrichment. Animals were fed standard rabbit food pellets and autoclaved hay ad libitum in accordance with the standard care protocols, and were fed with Critical Care (OxBow, USA) after the surgery. Water was provided ad libitum and cages were cleaned once a week. Animals were checked daily, and weighed daily in the first week after surgery or until their weight had normalised. Hereafter, animals were weighed bi-weekly throughout the study period. Humane endpoints included pain not responding to the maximum dose of analgesics, loss of appetite for 24 h, weight loss of more than 15% (excluding birth trial), infection not responding to treatment, and/or prolonged or arrested labour.

Mating and birth protocol

Female rabbits were placed into the male rabbit cage under supervision. Mating usually occurred immediately, and the female was then removed. If mating did not occur within the first few minutes, the females were removed again. This procedure was repeated three times within 48 h. Three days after this cycle, the females were transferred back to the male rabbit cage for a single re-breeding attempt, which concluded a breeding cycle. On day 25, one breeding box per mother was placed into the cages. From day 28 and onwards, all mated rabbits were under 24/7-hour video surveillance in case of labour. On day 31 or 32, all rabbits went into labour. After labour, the pups were assessed for signs of birth trauma and weighed. Approximately three days after labour, the mother and pups were sacrificed.

Euthanasia and autopsy

Adult rabbits were given an intracardiac injection with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg) under ample anaesthesia with ketamine (30 mg/kg IM) and xylazine (5 mg/kg IM). Pups were euthanised with cervical dislocation. Autopsy of adult female rabbits involved gross inspection of all abdominal organs. The vagina was inspected and removed. Vaginas from rabbits that were euthanised after two weeks were placed into neutral formalin buffer 10% (Hounisen, Denmark), and vaginas from rabbits that were euthanised after seven months were inspected and photographed on 1 cm grid paper prior to fixation. In some cases, the vagina was cut with an anterior incision for gross inspection of the luminal cavity (Fig. 2a). Cut vaginas were closed using running sutures (Prolene® 4-0) before placing them in formalin. A test tube with an outer diameter smaller than the vaginas (12 mm, Fisher Scientific, SE) was inserted into the vaginal canal to maintain their circular shape during formalin fixation for the seven-month vaginas.

Histology processing

After 24 h of formalin fixation, the vaginas were processed for histology. The graft zones were identified macroscopically from the remaining stay sutures, and the graft zones were cut into five consecutive transverse segments. The first and last segments represented the edges of the graft zones, and the middle three segments represented the core of the graft zones. Each segment was placed into a sectionable cassette system (Tissue-Tek® Paraform®, Sakura, USA) and labelled before paraffin embedding. The blocks were sectioned at 3 μm, and stained with Masson’s trichrome, hematoxylin and eosin, or immunohistochemistry in accordance with standardised clinical practice protocols, the latter involving positive controls that were validified by a board-certified clinical pathologist. We used pan-cytokeratin (clone AE1/AE3, ID: GA053, DAKO Agilent, USA) Collagen IV (clone CIV 22, ID: 760-2632, Roche, Switzerland), and smooth muscle myosin (clone SMMS-1, ID: 760-2704, Roche, Switzerland). Slides were scanned using a slide scanner at 40X magnification (Visiopharm Oncotopix scan, Hamamatsu, Japan).

Histology quantifications

Graft zones were labelled by two blinded investigators (OW and CE) on the Masson’s Trichrome slide by using an Image analysis software package (Version 2020.08.4.9377, Visiopharm, DK). Based on the graft zone markings from each investigator, the length, thickness and transverse cross-sectional areas were calculated using an automated tool for dimension measurements, and the mean value was presented. The cytokeratin and smooth muscle myosin concentrations, and the collagen:muscle ratios were calculated using another Visiopharm machine learning application that was trained to detect and quantify the positive area within a region of interest using Bayesian linear regression (Supplementary Fig. 4a–c). Collagen:muscle ratios were calculated as the mean area of collagen divided by the mean area of muscle. 16,202 vascular structures were manually marked and counted by one blinded investigator (MA) under 40X magnification using Image J software (NIH, USA). The values were both presented as absolute numbers and as vascular densities relative to one of the investigator’s graft zone markings All graft zone markings can be found in Supplementary Fig. 7.

Tissue sampling for experimentation

Tissue samples for the experiments were collected immediately after euthanasia. A 5 × 5 mm full thickness biopsy was harvested 10 mm from the edge of the graft zones (PLATE and acellular graft recipients) or from the same anatomical region (control rabbits). The biopsies were placed directly into RNALater (Thermo Fisher, USA) and stored at 4 °C. After 2–7 days, the liquid component was removed, and the samples were frozen bulk analysis at a later stage. Vaginal tissue for histological evaluation was collected after euthanasia. The organs were divided into 5 mm transverse sections centred around the graft zones and fixed in formalin (10%, Hounisen, Denmark).

RNA extraction

34 tissue samples, including seven samples harvested during a preliminary pilot experiment9, were removed from the freezer, and up to 30 mg of frozen tissue was transferred to a 2 mL tube containing steel beads and 0.5 mL lysis buffer (RLT buffer Qiagen, Valencia CA; product No. 217684). The tubes were placed in the precooled tissue-lyser LT scaffold (Qiagen, product nr. 85600) and homogenised for 50 sec over two cycles. Each cycle was accompanied by a cooling time on ice for 30 s. RNA was isolated from the homogenised samples by using the miRNeasy Tissue/cells advance kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) by following the manufacturer’s instructions. In brief, genomic DNA and proteins were eliminated by using a DNA eliminator spin column, and proteins were eliminated by using a protein precipitating reagent (PPR) and Proteinase K step. The resulting RNA solutions were next applied to a RNeasy Mini Spin Column. RNAs were eluted in 30 µl volume of RNase-Free Water. The RNA concentration and quality were evaluated using Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer and 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), respectively, at Karolinska Institutet, KIGene Core Facility. Based on the RNA integrity number and concentration, 16 samples, across all conditions, were selected for sequencing.

Library construction

We processed the RNA samples for sequencing using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded mRNA (polyA) library kit. These fragments underwent sequencing on a NovaSeq 6000 system. We converted Bcl files to FastQ format with the assistance of the CASAVA software. The quality measurement adhered to the Sanger/phred33/Illumina 1.8+ scale. The National Genomics Infrastructure in Genomics Production Stockholm oversaw the quality assessment, focusing on factors like yield, read quality, and any potential cross-contamination between samples. After demultiplexing and conversion to FastQ format on location, we then uploaded the data to UPPMAX for delivery.

RNA-seq data analysis

The quality of the FastQ reads was controlled using FastQC (http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc). Low-quality and adapter reads were trimmed by FastP36. Then, the reads were aligned to the rabbit reference genome OryCyn 2.0, using HISAT2 v2.2.137. Protein coding genes were annotated based on Ensembl release 10838. A count matrix was generated by featureCounts39.

Bioinformatics

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified and visualised in Qlucore Omics Explorer v. 3.9 (Qlucore AB, Lund, Sweden). Genes were considered differentially expressed between two conditions if p < 0.05 and with an absolute fold-change >2. Visualisations included principal component analysis (PCA), heat maps with two-way unsupervised hierarchical clustering, and boxplots. STRINGDB (www.string-db.org) and Ingenuity Pathway analysis (QIAGEN IPA) were used for functional enrichment, network, and pathway analyses. The expression data are deposited in Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO).

Statistical methods

Mean values were calculated by averaging the values from both blinded investigators, “ ± ” and error bars on all bar charts represent standard error of the mean (SEM) unless otherwise stated. Each circular dot on the bar charts represented a value from one biological replicate. A Bayesian linear regression-based machine learning method within the Visiopharm software was trained to detect and categorise positive, negative and background regions within regions of interest for comparison between groups. Statistical calculations were made using Microsoft Excel version 16.73 (Microsoft, USA). The p-values were calculated using two-tailed Student’s t tests for equal variance, and two-tailed Welch’s t test for unequal variance, determined by a variance ratio of less than or more than 4, respectively. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Responses